Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.34 no.1 Pretoria ene. 2014

Teacher beliefs and practices of grammar teaching: focusing on meaning, form, or forms?

Hacer Hande UysalI; Mehmet BardakciII

IGazi University, Turkey uysalhande@yahoo.com

IIGaziantep University

ABSTRACT

Despite the worldwide curriculum innovations to teach English through meaning-focused communicative approaches over the years, studies report that most language teachers still follow transmission-based grammar-oriented approaches. It is known that the success of any curriculum innovation is dependent on teachers. Therefore, given that teaching grammar has always been a central, but problematic domain for language teachers, what teachers believe and do regarding grammar instruction is an important issue that needs to be investigated. However, studies that research teachers and their grammar teaching are rare, and almost non-existent at the elementary-level English teaching contexts. Therefore, through a questionnaire given to 108 teachers and afocus-group interview, the present study investigated Turkish primary-level English language teachers' beliefs and practice patterns of teaching grammar, and the reasons behind these patterns. The results revealed that teachers predominantly prefer the traditional focus-on-formS approach, which indicates a serious clash with teachers and curriculum goals, on the one hand, and theoretical suggestions on the other. The paper ends with discussions and suggestions for teacher education and language policy-making.

Keywords: English as a foreign language (EFL); English as a second language (ESL); grammar; teacher beliefs; teacher practices; young learners

Introduction

How grammar is best acquired and taught has been a major issue at the centre of many controversies in second language acquisition research. It becomes even more controversial when young learners are concerned. Research and discussions on grammar teaching have recently focused on three options - "focus-on-formS," "focus-on-meaning," and "focus-on-form" (Long, 1991:45-46). In focus-on-formS instruction, language is divided into isolated linguistic units and taught in a sequential manner through explicit explanations of grammar rules and immediate correction of errors (Long, 2000). Classes follow a typical sequence of "presentation of a grammatical structure, its practice in controlled exercises, and the provision of opportunities for production-PPP" (Ellis, Basturkmen & Loewen, 2002:420). The underlying logic of this approach is that the explicit knowledge about grammar rules will turn into implicit knowledge with enough practice (De Keyser, 1998).

Focus-on-meaning, on the other hand, which was informed by Krashen and Terrell's (1983) Natural Approach to second language (L2) acquisition, completely refuses any direct instruction on grammar, explicit error correction, or even consciousness-raising, as L2 is claimed to be naturally acquired through adequate exposure to language or "comprehensible input" (Krashen, 1982:64; Krashen, 1985:2). According to this view, explicit knowledge about language and error correction is unnecessary and even harmful as it may interfere with the natural acquisition process in which learners would subconsciously analyse the forms and eventually deduce the rules from the language input themselves. Thus, this position claims that there is no interaction between explicit and implicit knowledge; therefore, conscious learning is different and cannot lead to language acquisition (Krashen, 1982; Larsen-Freeman, 2003).

However, both focus-on-formS and pure focus-on-meaning have been subject to serious criticism (Long, 1991; 2000). Focus-on-formS has been criticized for being teacher-centred, artificial, boring, and for not allowing meaningful communication and interaction, which are essential to language acquisition (Long, 2000). Focus-on-meaning also has been called into question based on the empirical evidence that mere exposure to a flood of language input with no attention to grammar or error correction results in fossilization and poor L2 grammar in language production (Doughty & Williams, 1998; Higgs & Clifford, 1982; Lightbown & Spada, 1994; Skehan, 1996; Swain, 1985; Swain & Lapkin, 1995; White, 1987). Furthermore, it was suggested that some grammatical forms, especially those which are in contrast with the students' first language, that are infrequent in input, and that are irregular cannot be acquired simply through exposure (White, 1987; Larsen-Freeman, 2003; Sheen, 2003).

As a result, scholars attempted to reconcile form with meaning. Thus, "focus-on-form," which was defined as "any planned or incidental instructional activity that is intended to induce language learners to pay attention to linguistic forms" (Ellis, 2001:1-2) during meaningful communication (Long, 1991) was introduced to the field. Having been informed by Schmidt's (1990, 1993) Noticing and Consciousness-Raising Theory and Swain's (1985) Output Hypothesis, this view proposes that some sort of noticing and consciousness-raising to target grammar structures in input, and feedback on errors during language use in meaningful communicative activities would facilitate the acquisition of language (Doughty & Williams, 1998; Ellis, 2002; Long, 1991, 2000; Song & Suh, 2008; Swain, 1998, 2005). Such noticing or consciousness-raising was stated to contribute to language acquisition in three ways: "learning will be faster, quantity produced will be greater, and contexts in which the rule can be applied will be extended" (Rutherford, 1987:26).

Substantial empirical evidence from studies, including the ones conducted with children, has provided support forfocus-on-form compared to other grammar teaching approaches. For example, a meta-analysis of 49 studies by Norris and Ortega (2000, 2001) and 11 studies by Ellis (2002) demonstrated that focus-on-form contributed to faster language acquisition, higher levels of accurate oral or written language production, and longer retention of forms when compared to pure meaning-focused implicit learning. Among the analysed studies, four involved young learners. Some other studies conducted with children in Grades 2,4 and 5 in French immersion and intensive language programmes in Canada also provided evidence that some input enhancement and attention-taking to certain grammatical features, along with communicative language use have a positive and long-lasting effect on L2 proficiency compared with pure communicative focus (Harley, 1998; Spada & Lightbown, 1993; White, Spada, Lightbown & Ranta, 1991, Wright, 1996). In addition, perceptions of primary-level EFL students on focus-on-form tasks were found to be very positive (Shak & Gardner, 2008). Therefore, recently, the benefits of focus-on-form over other approaches have been widely acknowledged (Spada & Lightbown, 2008), and the current discussions are diverted to finding the most effective means to implement this approach in classrooms (Flowerdew, Levis & Davies, 2006; Doughty & Williams, 1998; Nassaji, 1999; Spada & Lightbown, 2008; Uysal, 2010).

These developments in the second language acquisition research, however, have not made their way into language policy and classroom pedagogy in most EFL/ESL contexts in the world. For example, many large-scale national curriculum reforms around the world have targeted mainly one end - the meaning-focused communicative approach by encouraging implicit learning of grammar in many regions such as Europ e (Nikolov & Curtain, 2000) and Asia-Pacific region (Nunan, 2003). However, because meaning-focused language teaching, which merely targets communicative competence, can lead to fossilization and weak grammatical competence, it was seen as inadequate for developing academic English skills, which are based on accurate and appropriate grammatical use (Peirce, 1989; Swain & Lapkin, 1995). As English has already become a global lingua-franca and the language of power in many contexts in the world, grammatical usage and accurate language use is especially necessary for EFL/ESL learners who need English for economic empowerment and upward mobility in many societies (Peirce, 1989; De Wet, 2002).

Specifically in Turkey, in 1997 and 2005, two major complementary educational reforms took place, initiated by the Ministry of National Education (MEB). This innovation aimed at starting English from Grade 4 and introducing a meaning-focused communicative approach to the Turkish language education context, which was used to be driven by mainly the traditional approaches to grammar teaching around the "focus-on-formS" approach for years. Yet, this unrealistic radical shift from one end to another in a very short time could not find a way into teachers' actual classroom teaching. Instead, despite the government-initiated meaning-oriented reform movements, most language teachers have been faced with difficulties with communicative language teaching (CLT). Thus, they followed the familiar teacher-centred traditional grammar teaching methods both in Turkey (Krrkgõz, 2007, 2008a, 2008b; Uysal, 2012) and in other EFL/ESL contexts due to various reasons, such as teachers' and students' low proficiency in English, time constraints, lack of materials, low student motivation, noise and classroom management problems, grammar-based examinations, clash of western and eastern cultural values, first language (L1) use during group work activities, limited resources and exposure to English, and lack of teacher training in CLT (Carless, 2002; De Wet, 2002; Gorsuch, 2000; Karavas-Doukas, 1996; Li, 1998; Nishino & Watanabe, 2008; O'Connor & Geiger, 2009; Prapaisit de Segovia & Hardison, 2009; Sakui, 2004; Sato & Kleinsasser, 1999; Ting, 2007). These findings indicate serious discrepancies and contradictions among teachers' practices, curriculum goals, and the theoretical suggestions, thus further corroborating that grammar in language teaching and learning continues to be an obscure and "ill-defined domain" far from offering solid guidelines for teachers (Borg, 1999a:157) and policy makers.

In the middle of these oppositions and contradictions, how language teachers deal with grammar is critical and central with regards to curriculum innovations (Saraceni, 2008). Therefore, what teachers believe and do regarding grammar instruction is an important issue that needs to be investigated. Yet, the issue has only recently received attention and mostly in ESL university settings or language centres. For example, few such studies investigated teacher beliefs regarding grammar teaching and found that teachers in general believe that grammar is central to language learning and students need direct and explicit teaching of grammar rules for accuracy (Burges & Ethe-rington, 2002; Ebsworth & Schweers, 1997; Potgieter & Conradie, 2013). Some other studies looked at the relationship between teacher cognition and classroom behaviors and the reasons behind them. The results of these studies revealed that teacher beliefs were often inconsistent with practices, and teacher behaviours are formed by both personal factors such as teachers' prior learning experiences of grammar such as deductive versus inductive (Farrell, 1999; Johnston & Goettsch, 2000) or teachers' knowledge of grammar rules (Borg, 2001); and contextual constraints such as the education system, curriculum, administration, examinations, and student expectations (Borg, 1998, 1999a, 1999b; Farrell, 1999; Phipps & Borg, 2009; Richards, Gallo & Renandya, 2001).

Nonetheless, Ellis et al. (2002:419) state that still not much is known about "the actual methodological procedures that teachers use to focus on form". Empirical research into what teachers believe and do regarding teaching grammar is also reported to be inadequate (Ellis et al., 2002), especially at the elementary level in EFL contexts. For example, Farrell & Lim (2005) is the only study conducted on teacher beliefs and practices of grammar teaching at elementary level in an EFL context (Singapore). This study found that teachers believed that grammar teaching is crucial for enabling students to use grammar structures correctly and favoured a traditional deductive approach involving direct teaching and explaining rules for grammar structures, drilling, and error correction as it is less time-consuming and leads to accurate language use. The teachers also expressed doubts about incidental language teaching as it could be confusing for students.

Therefore, given the importance of the issue and scarcity of research on teacher beliefs and practices of grammar teaching, particularly at elementary-level EFL contexts, the present study aimed to explore the issue in the Turkish context by examining Turkish primary-school EFL teachers' beliefs and classroom practices in terms of grammar teaching. The data were collected through a questionnaire given to 108 teachers and a focus-group interview to explore teachers' stated belief and behaviour patterns, as well as the reasons behind these patterns. The research questions which guided the study were:

1. What are teachers' beliefs about the way grammar should be taught?

2. What are teachers' stated practices of teaching grammar?

3. What are the reasons behind the belief and behaviour patterns?

Methodology

Participants

This study consisted of 108 EFL teachers teaching the fourth and fifth grades in state schools in Ankara. The teachers participated in the study on a voluntary basis. As for the demographics of teachers, 12% of the teachers were males and 88% were females. 47% of the teachers held a BA degree in English language teaching, 20% of them a BA in English or American literature, and 5.5% a BA in linguistics. 27% of them majored in a different area in an English-medium university. As far as the years of experience in teaching are concerned, 9% of the respondents had zero to four years, 63% of them had five to nine years, 17% of them had 10 to 14 years, 8% of them had 15 to 19 years, and 3% of them had over 20 years of teaching experience.

Procedure

The data were collected from 42 randomly selected state schools in two regions of Ankara mainly through a questionnaire adapted from Zucker's (2007) study to understand the stated belief and behaviour patterns of teachers. Then, a focus-group interview with 10 teachers, who were randomly selected among volunteers, was conducted to accomplish an in-depth understanding of teacher perspectives and experiences of grammar teaching and to explore the possible factors behind their common belief and practice systems. A focus-group interview was chosen because it was reported to have a higher validity due to the larger number of participants (Vauguh, Schumm & Sinagub, 1996, quoted in Dushku, 2000), revealing data on group interaction in a group context (Dushku, 2000; Frey & Fontana, 1993), and being a faster means of obtaining maximized information (Walker, 1985).

The descriptive frequency analysis of the prevalent teacher beliefs and practices was conducted. In order to find the reliability of the scale, Cronbach's alpha analysis was applied, and it was found to be .703, which is an accepted valid value. In addition, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and an independent t test were conducted to see whether teachers' educational background, gender, and teaching experience have any effect on the findings.

Results

Behaviours

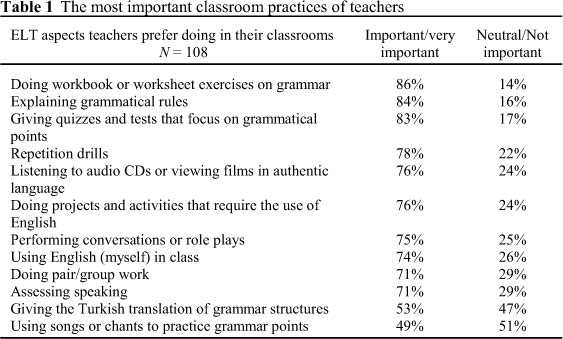

It was revealed that the most important English language teaching (ELT) classroom practices according to the teachers were concerned with doing workbook or worksheet exercises on grammar (86%), explaining grammar rules (84%), giving quizzes on grammatical points (83%), and repetition drills (78%). These highly prioritized practices in general represented the traditional grammar teaching approaches. The communicative activities such as conversations and role-plays (75%),pair/group work (71%), and songs or chants (49%), on the other hand, only came after these traditional aspects. Table 1 demonstrates these results.

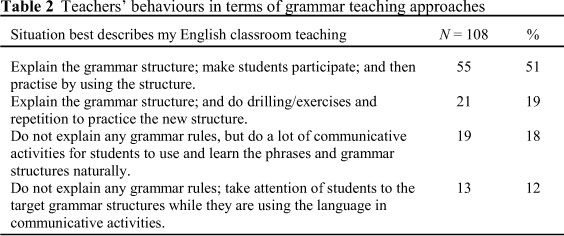

It was also found that 70% of teachers follow a deductive approach by first explicitly and directly explaining the grammar rules, reflecting a focus-on-formS approach. Among these, 21 teachers (19%) teach grammar through controlled practice with drills; yet, 55 of them (51%) allow students to practise grammar structures later by actually using the language, reflecting a more eclectic method. 19 teachers (18%) were found to do pure meaning-focused communicative language teaching, and only 13 teachers (12%) were found to do focus-on-form. The results can be seen in Table 2.

Beliefs

As for the beliefs, the teachers surveyed were found to be quite conservative, because their thoughts and beliefs tended to be more in line with traditional approaches and processes with regards to language learning and teaching. For example, 95 teachers (88%) stated that mechanical drills, exercises, and repetitions are necessary and/or helpful to support language acquisition; and 90 teachers (84%) reported that they do not believe that English can be acquired without explicit grammar instruction. 93 teachers (86%) also agreed that a grammar concept can be explained in Turkish (L1) when students do not understand. The focus-group interview shed further light on teachers' beliefs about grammar teaching. First, except for the two female teachers, all teachers interviewed believe that explicit grammar teaching works better than the natural implicit approach. Teachers agreed that "complete exclusion of grammar is not a right thing to do because students may or may not deduce the rules by themselves." Some said "it would be very cruel not to explain grammar to students". Teachers believed that after a certain time, especially beyond fifth grade, students need to analyse and understand grammar consciously," and sometimes they feel the need to compare English structures to L1 or find the meaning in L1. According to most teachers, "if the students do not know the rules, they can't make new sentences, they just repeat and memorize the already given ones, but they should analyse the rules in order to make new sentences." Teachers also echoed that especially "the more difficult the grammar topics are, the more impossible it gets to teach implicitly." The two teachers who believed in the merits of CLT also said they "sometimes explain grammar rules, and this helps students to make better sentences, otherwise students only learn words".

The results of the independent t test also revealed that male teachers agreed significantly more to the idea of explaining a grammar concept to students in Turkish if they seem not to understand than their female colleagues (p < .05)1. Males were also found to use explanation of grammar rules, repetition drills (p < .05), and quizzes and tests (p < .01) more than females. According to the ANOVA results, there was no significant correlation between other demographic variables and teacher beliefs and practices.

Reasons behind the belief and behaviour patterns

As for the reasons affecting classroom teaching, according to the questionnaire, the three most important factors were the Ministry of National Education curriculum (25%), student expectations (18%), and the textbook (15%). Then, the way teachers themselves learned English (11%), in-service professional development opportunities (11%), research-based readings (10%), and collaboration with another teacher (7%) were found to influence the behaviours. The most interesting finding was that pre-service teacher-preparation courses were stated to have only 3% of influence on teacher behaviours.

The focus-group interview helped reveal, especially, the contextual causes of the traditional teacher beliefs and behaviours of grammar teaching and failures of application of CLT in detail. The first factor found was the time constraints (three hours a week). According to the teachers "although the new curriculum and textbooks aimed to enable students to go through an acquisition process, there is not enough course time for exposing students to English to realize this goal. So, students need to consciously learn certain rules, and the rules should be mentioned." Teachers said "we cannot complete the book and fall behind because teaching implicitly just by creating situations and showing pictures is very time consuming, and we should cover the entire book because students will have questions from the book in the central standardized exams by the government; so we need to teach explicitly to save time."

Crowded classes, low student motivation, and classroom management issues were also frequently mentioned. One teacher said "it is not possible to make 40 students to participate in activities in a 40 minute class." "Students make a lot of noise, teachers have no right to control students, and we can't even send the problematic students out." "Students don't care because we can't fail students in primary schools, they pass anyway." "Only 10% of the students are motivated to learn and this group learns whatever approaches you apply. But the majority is problematic." In addition, "the classrooms, in which students sit in strict rows do not let us perform communicative activities."

Another problem was the textbooks. Teachers described the textbooks by MEB as having no explicit grammar teaching and expecting students to implicitly learn grammar while speaking and through repetitions. One teacher said she "wanted to implement CLT, exactly followed the book, stopped teaching grammar topics and rules, but her students did not seem to learn English any better." Another teacher said she strongly supports CLT and believes that grammar could be learned implicitly; yet, she finds books "inadequate to realize this goal as the books are very poor in terms of communicative activities and visual materials." "Besides, the books only focus on words; thus, students at the end cannot make sentences or express their ideas just with words, and they cannot write."

"The textbooks are inadequate, I know there are other really good imported books, resources, and worksheets, but in this book there is nothing when you take out the pictures; we need more materials and a more activity-based book. We have to find our own materials from the Internet, but not sure whether they are appropriate or not."

One teacher said "the book emphasizes speaking, but it expects students to learn grammar as well without teaching; this is a contradiction." Another teacher said

"there is a grammar reference list at the end of the books, but in the units there are no boxes or special focus on grammar. There can be boxes in which target grammar topics are introduced just like 'Headway' and 'Cutting Edge'. Students cannot understand what they should learn and what is going to be asked in exams."

According to the teachers, the reform and the SBS (the major central exam at primary level) were not in parallel. Some said that

"although SBS is based on vocabulary and looks like meaning-based (some disagreed), students can do the test without understanding or knowing the meaning of the words, but by just looking at the pictures and matching them with the appropriate word or sentence."

"Students developed strategies so that they can select the multiple choices, but cannot produce language. The central exam does not have a listening and speaking component; so, it is not really meaning-based."

Teachers said because SBS is not really communicative, they need to prepare students for SBS; thus, they explicitly teach rules and vocabulary.

Teachers also mentioned cultural and L1 related problems. For example, teachers said that "students have problems in their first language, they do not read books; so, they do not even understand what they read in Turkish." Teachers also said "students don't know the grammar, what verb or adjective means in L1. Sometimes we have to teach these things in Turkish in order to proceed." As for the culture, teachers also mentioned that

"students in our country are used to receiving everything from the teacher and get explicit explanations; they easily get tired when you expect too much from them and they give up when they cannot understand the rule, so you have to explain after a certain point."

Finally, teachers mentioned the lack of special training in teaching English to young learners and said

"none of us received a special education to teach such young learners. The things we know are just the things we hear from others, some of them are right, some are wrong. We do not know songs in English. At the universities there is no special division to educate teachers for primary school English teaching."

Teachers were also not familiar with focus-on-form approaches, and they were particularly interested in how ELT is practised in other countries.

Conclusions and discussion

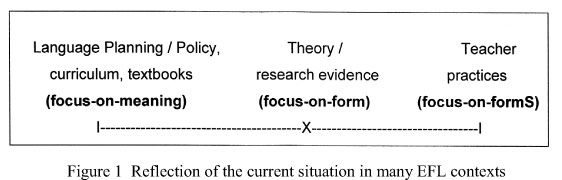

In summary, most teachers favoured the beliefs that represent traditional approaches to grammar teaching such as the use of explicit grammar teaching followed by controlled practice, use of L1, mechanical drills and repetitions. The most common classroom practices of teachers were also mostly related to teaching, practising, and testing of grammar. Communicative activities were reported as important only after the traditional practices. The majority of teachers were found to use translations into L1, teacher-centred instruction, and deductive and explicit approaches to grammar teaching, with or without a controlled practice component. The teachers were also found to be unfamiliar with a focus-on-form approach and only a few mentioned practices reflecting this approach in the questionnaire and interview. Therefore, it can be concluded that, in general, both teacher beliefs and practices reflect a traditional focus-on-formS approach to grammar teaching. This finding indicated a gap between the teacher beliefs/practices and the recent developments in second language acquisition research. This finding also pointed out a severe divergence of the teaching practices from the curriculum goals in Turkey, which is similar to the findings of other studies that revealed incongruence between curriculum innovations and teacher behaviours, such as Li (1998), Sato & Kleinsasser (1999), Sakui (2004), and Ting (2007). These results, therefore, confirm the suggested situation in Figure 1 regarding the discrepancies among recent global curriculum reforms, L2 acquisition theory, and teacher practices in EFL contexts.

In terms of the reasons behind the teaching beliefs and practices, although the majority of teachers claimed that MEB curriculum and textbooks (40%) are the determining factors in their classroom teaching in the questionnaire; interview results revealed that, in fact, teachers have serious concerns with the meaning-oriented communicative curriculum and the textbooks. From teachers' accounts it was found that they did not believe that the new innovations could be employed in their own classroom contexts, and thus most teachers developed their own working practices demonstrating a more traditional explicit deductive method of grammar teaching (focus-on-formS) due to factors such as time constraints, crowded classes, low student motivation, noise and classroom management problems, textbooks, central examinations, cultural and L1-related problems, and their lack of special training in teaching English to young learners. Both teachers' concerns and the reasons behind their practices were similar to previous studies reporting problems with pure meaning-focused teaching in other contexts such as Li (1998) and Sakui (2004).

Implications for teacher education and language policy making

One of the most striking findings of the study was that pre-service education in ELT programmes in universities had little or no effect on teachers' beliefs and practices regarding grammar teaching. As Pajares (1992) states, teachers' beliefs and practices seem to be formed, not by their pre-service education, but through a process of encul-turation and social construction once they started teaching. Therefore, both pre- and in-service ELT professional education should deal with the issue of teaching grammar, as many teachers' classroom practices and belief patterns in particular were found to be very conservative. The teachers expressed their feelings of discomfort and doubts with the new curriculum that is based on pure meaning-focused communicative approaches, resulting in their sticking to the old, but familiar focus-on-formS approaches. It was also found that teachers were not familiar with the focus-on-form approach and recent developments in L2 acquisition research.

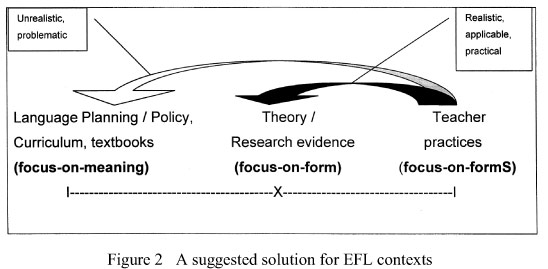

Therefore, any professional teacher education programme or future curricula should be designed in accordance with the recent theoretical developments in grammar teaching. This requires equipping teachers with the necessary knowledge base and skills to be able to focus students' attention on form during communicative activities - a focus-on-form approach - rather than imposing a pure meaning-based communicative teaching on teachers excluding grammar altogether, which was found as utopic by teachers and problematic by research in general. From recent research, it is evident that students do not automatically pay attention to grammatical features during natural communication; therefore they need the guidance of teachers to help them attend to certain forms. Therefore, grammar instruction should be integrated with meaning while teaching English to young learners in primary classrooms through a focus-on-form approach. Cameron (2001:96) suggests that grammar is not beyond children's cognitive capacity and grammar definitely has a place in children's learning of language because "it is closely tied into meaning and use of language, and is inter-connected with vocabulary". An early start to grammar instruction with children is further supported as a preventive measure to protect children from ambiguous classroom input and fossilization of incorrect forms (Harley, 1998:161). An early start with English and developing grammatical accuracy is also preferred by children and their parents and seen as important to empowering disadvantaged ESL learners in certain contexts (Ngidi, 2007; Peirce, 1989). Therefore, instead of trying to leave the grammar out of classrooms altogether, the aim in teacher education and language planning should be to move from focus-on-formS to a focus-on-form approach rather than to focus on meaning.

Considering the local contextual factors and taking a more "context-sensitive" ecological perspective (Bax, 2003:233), moving from focus-on-formS to a focus-on-form rather than shifting radically to a "focus-on-meaning" may be more realistic and practical. Unfortunately, top-down curriculum reforms, textbook developers, and teacher trainers not only ignore research results, indicating limited success of pure communicative applications in classes, they also assume, and insist, that CLT is the ultimate solution, ignoring teachers' views and needs, and neglecting the local realities (Bax, 2003; Hu, 2005). As evidenced by the interview results, Turkish teachers, as was the case with the teachers in other EFL/ESL contexts, have many problems with the application of pure meaning-based CLT and do not see it as applicable and realistic in their own classrooms. A middle way, therefore, may be more plausible and applicable in the EFL classroom contexts characterized by crowded classes, limited classroom time, inadequate exposure to language input and output practice, pressures of accuracy-based tests, and inadequate fluency of teachers in English (Carless, 2002; Fotos, 1998, 2002; Nishino & Watanabe, 2008).

References

Bax S 2003. The end of CLT: A context approach to language teaching. ELT Journal, 57:278-287. doi: 10.1093/elt/57.3.278 [ Links ]

Borg S 2001. Self-perception and practice in teaching grammar. ELT Journal, 55(1):21-29. doi: 10.1093/elt/55.1.21 [ Links ]

Borg S 1999a. Teachers' theories in grammar teaching. ELT Journal, 53(3):157-167. Available at http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/content/53/3/157.full.pdf. Accessed 19 December 2013. [ Links ]

Borg S 1999b. Studying teacher cognition in second language grammar teaching. System, 27(1):19-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(98)00047-5 [ Links ]

Borg S 1998. Teachers' pedagogical systems and grammar teaching: A qualitative study. TESOL Quarterly, 32(1):9-38. Available at http://www.education.leeds.ac.uk/assets/files/staff/papers/Borg-TQ-32-1.pdf. Accessed 19 December 2013. [ Links ]

Burgess J & Etherington S 2002. Focus on grammatical form: explicit or implicit? System, 30:433-458. Available at http://www.finchpark.com/courses/grad-dissert/articles/grammar/grammar-exclicit-or-implicit.pdf. Accessed 19 December 2013. [ Links ]

Cameron L 2001. Teaching languages to young learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Carless D 2002. Implementing task-based learning with young learners. ELT Journal, 56(4):389-396. Available at http://203.72.145.166/ELT/files/56-4-5.pdf. Accessed 19 December 2013. [ Links ]

De Keyser RM 1998. Beyond focus-on-form: Cognitive perspectives on learning and practicing second language grammar. In C Doughty & J Williams (eds). Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

De Wet C 2002. Factors influencing the choice of English as language of learning and teaching (LoLT) -A South African perspective. South African Journal of Education, 22:119-124. Available at http://www.ajol.info/index.php/saje/article/viewFile/25118/20554.The. Accessed 19 December 2013. [ Links ]

Doughty C & Williams J 1998. Pedagogical choices in focus on form. In C Doughty & J Williams (eds). Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dushku S 2000. Conducting individual and focus-group interviews in research in Albania. TESOL Quarterly, 34(4):763-768. doi: 10.2307/3587789 [ Links ]

Ebsworth ME & Schweers CW 1997. What researchers say and practitioners do: Perspectives on conscious grammar instruction in the ESL classroom. Applied Language Learning, 8:237-260. [ Links ]

Ellis R 2002. Does form-focused instruction affect the acquisition of implicit knowledge? A review of the research. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24(2):223-236. [ Links ]

Ellis R 2001. Introduction: Investigating form-focused instruction. Language Learning, 51(s1):1-46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.2001.tb00013.x [ Links ]

Ellis R, Basturkmen H & Loewen S 2002. Doing focus-on-form. System, 30(4):419-432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(02)00047-7 [ Links ]

Farrell TSC 1999. The reflective assignment: Unlocking pre-service teachers' beliefs on grammar teaching. RELC Journal: A journal of language teaching and research, 30(2):1-7. doi: 10.1177/003368829903000201 [ Links ]

Farrell TSC & Lim PCP 2005. Conceptions of grammar teaching: A case study of teachers' beliefs and classroom practices. TESL-EJ, 9(2):1 -13. Available at http://tesl-ej.org/ej34/a9.pdf. Accessed 8 January 2014. [ Links ]

Flowerdew J, Levis J & Davies M 2006. Paralinguistic focus-on-form. TESOL Quarterly, 40(4):841-855. doi: 10.2307/40264316 [ Links ]

Fotos S 2002. Structure-based interactive tasks for the EFL grammar learner. In E Hinkel & S Fotos (eds). New perspectives on grammar teaching in second language classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Fotos S 1998. Shifting the focus from forms to form in the EFL classroom. ELT Journal, 52(4):301-307. doi: 10.1093/elt/52.4.301 [ Links ]

Frey JH & Fontana A 1993. The group interview in social research. In DL Morgan (ed). Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Gorsuch GJ 2000. EFL Educational policies and educational cultures: Influences on teachers' approval of communicative activities. TESOL Quarterly, 34(4):675-710. doi:10.2307/3587781 [ Links ]

Harley B 1998. The role of focus-on-form tasks in promoting child L2 acquisition. In C Doughty & J Williams (eds). Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Higgs T & Clifford R 1982. The push toward communication. In T Higgs (ed). Curriculum, competence and the foreign language teacher. Skokie, IL: National Textbook Company. [ Links ]

Hu G 2005. 'CLT is best for China'- An untenable absolutist claim. ELT Journal, 59(1):65-68. doi: 10.1093/elt/cci009 [ Links ]

Johnston B & Goettsch K 2000. In search of the knowledge base of language teaching: Explanations by experienced teachers. Canadian Modern Language Review, 56:437-468. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.56.3.437 [ Links ]

Karavas-Doukas E 1996. Teacher identified factors affecting the implementation of an EFL innovation in Greek public secondary schools. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 8(1):53-68. doi: 10.1080/07908319509525188 [ Links ]

Krrkgdz Y 2008a. Curriculum innovation in Turkish primary education. Asia-Pasific Journal of Teacher Education, 36(4):309-322. doi: 10.1080/13598660802376204 [ Links ]

Krrkgdz Y 2008b. A case study of teachers' implementation of curriculum innovation in English language teaching in Turkish primary education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(7):1859-1875. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016Zj.tate.2008.02.007 [ Links ]

Krrkgdz Y 2007. Language planning and implementation in Turkish primary schools. Current Issues in Language Planning, 8(2):174-192. doi: 10.2167/cilp 114.0 [ Links ]

Krashen S 1982. Principles and practice in second language acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press. [ Links ]

Krashen S 1985. The input hypothesis. Harlow: Longman. [ Links ]

Krashen S & Terrell T 1983. The natural approach: Language acquisition in the classroom. New York: Pergamon Press. [ Links ]

Larsen-Freeman D 2003. Teaching language: From grammar to grammaring. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle. [ Links ]

Li D 1998. "It's always more difficult than you plan and imagine:" teachers' perceived difficulties in introduction to the communicative approach in South Korea. TESOL Quarterly, 32(4):677-703. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/3588000. Accessed 9 January 2014. [ Links ]

Lightbown PM & Spada N 1994. An innovative program for primary ESL students in Quebec. TESOL Quarterly, 28(3):563-579. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/3587308. Accessed 9 January 2014. [ Links ]

Long MH 2000. Focus on form in task-based language teaching. In RD Lambert & E. Shohamy (eds). Language policy and pedagogy: Essays in honor of A Ronald Walton. Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Long MH 1991. Focus on form: A design feature in language teaching methodology. In K De Bot, R Ginsberg & C Kramsch (eds). Foreign language research in cross-cultural perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Nassaji H 1999. Towards integrating form-focused instruction and communicative interaction in the second language classroom: some pedagogical possibilities. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 55:385-402. [ Links ]

Ngidi SA 2007. The attitudes of learners, educators and parents towards English as a language of learning and teaching (LOLT) in Mthunzini circuit. Unpublished MA thesis. South Africa: University of Zululand. Available at http://uzspace.uzulu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10530/80/The%20Attitude%20of%20Learners,%20Educators%20%26%20Parents%20towards%20English%20-%20SA%20Ngidi.pdf.txt?sequence=3. Accessed 9 January 2014. [ Links ]

Nikolov M & Curtain H (eds.) 2000. An early start: Young learners and modern languages in Europe and beyond. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [ Links ]

Nishino T & Watanabe M 2008. Communication-oriented policies versus classroom realities in Japan. TESOL Quarterly, 42(1):133-138. doi: 10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00214.x [ Links ]

Norris JM & Ortega L 2001. Does type of instruction make a difference? Substantive findings from a meta-analytic review. Language Learning, 51(s1):157-213. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.2001.tb00017.x [ Links ]

Norris JM & Ortega L 2000. Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A research synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis. Language Learning, 50(3):417-528. doi:10.1111/0023-8333.00136 [ Links ]

Nunan D 2003. The impact of English as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia-Pacific region. TESOL Quarterly, 37(4):589-613. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/3588214. Accessed 9 January 2014. [ Links ]

O'Connor J & Geiger M 2009. Challenges facing primary school educators of English Second (or Other) Language learners in the Western Cape. South African Journal of Education, 29:253-269. Available at http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/saje/v29n2/v29n2a07.pdf. Accessed 9 January 2014. [ Links ]

Pajares MF 1992. Teachers' beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3):307-332. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/1170741. Accessed 10 January 2014. [ Links ]

Phipps S & Borg S 2009. Exploring tensions between teachers' grammar teaching beliefs and practices. System, 37(3):380-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016Zj.system.2009.03.002 [ Links ]

Peirce BN 1989. Toward a pedagogy of possibility in the teaching of English internationally: People's English in South Africa. TESOL Quarterly, 23(3):401-420. doi: 10.2307/3586918 [ Links ]

Potgieter AP & Conradie S 2013. Explicit grammar teaching in EAL classrooms: Suggestions from isiXhosa speakers' L2 data. Southern African Linguistic and Applied Language Studies, 31(1):111-127. doi: 10.2989/16073614.2013.793956 [ Links ]

Prapaisit de Segovia L & Hardison DM 2009. Implementing education reform: EFI teachers' perspectives. ELT Journal, 63(2):154-162. doi:10.1093/elt/ccn024 [ Links ]

Richards JC, Gallo PB & Renandya WA 2001. Exploring Teachers' Beliefs and the Processes of Change. PAC Journal, 1(1):41-58. [ Links ]

Rutherford WE 1987. Second language grammar: Learning and teaching. NY: Longman, Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Sakui K 2004. Wearing two pairs of shoes: Language teaching in Japan. ELT Journal, 58(2):155-163. doi: 10.1093/elt/58.2.155 [ Links ]

Saraceni M 2008. Meaningful form: transitivity and intentionality. ELT Journal, 62(2):164-172. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccl052 [ Links ]

Sato K & Kleinsasser R 1999. Multiple data sources: Converging and diverging conceptualizations of lote teaching. The Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 24(1):17-34. doi: 10.14221/ajte.1999v24n1.2 [ Links ]

Schmidt R 1993. Awareness and second language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 13:206-226. Available at http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/PDFs/SCHMIDT%20Awareness%20and%20second%20language%20acquisition.pdf. Accessed 13January 2014. [ Links ]

Schmidt RW 1990. The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11(2):129-158. Available at http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/PDFs/SCHMIDT%20The%20role%20of%20consciousness%20in%20second%20language%20learning.pdf. Accessed 13 January 2014. [ Links ]

Shak J & Gardner S 2008. Young learner perspectives on four focus-on-form tasks. Language Teaching Research, 12(3):387-408. doi: 10.1177/1362168808089923 [ Links ]

Sheen R 2003. Focus on form-a myth in the making? ELT Journal, 57(3):225-233. doi:10.1093/elt/57.3.225 [ Links ]

Skehan P 1996. A framework for the implementation of task-based instruction. Applied Linguistics, 17(1):38-62. doi: 10.1093/applin/17.1.38 [ Links ]

Song MJ & Suh BR 2008. The effects of output task types on noticing and learning of the English past counterfactual condition. System, 36:295-312. doi:10.1016/j.system.2007.09.006 [ Links ]

Spada N & Lightbown PM 2008. Form-focused instruction: Isolated or integrated? TESOL Quarterly, 42(2):181-207. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/40264447. Accessed 13 January 2014. [ Links ]

Spada N & Lightbown P 1993. Instruction and the development of questions in the L2 classroom. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 15(2):205-224. [ Links ]

Swain M 2005. The output hypothesis: theory and research. In E Hinkel (ed). Handbook on research in second language teaching and learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Swain M 1998. Focus on form through conscious reflection. In C Doughty & J Williams (eds). Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Swain M 1985. Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In S Gass & C Madden (eds). Input in second language acquisition. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. [ Links ]

Swain M & Lapkin S 1995. Problems in output and the cognitive processes they generate: A step towards second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 16(3):371-391. doi:10.1093/applin/16.3.371 [ Links ]

Ting SH 2007. Is teacher education making an impact on TESL teacher trainees' beliefs and practices of grammar teaching? ELTED, 10:42-62. Available at http://www.elted.net/issues/volume-10/Su-Hie-Ting.pdf. Accessed 13 January 2014. [ Links ]

Uysal HH 2012. Evaluation of an in-service training program for primary-school language teachers in Turkey. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(7):14-29. doi:10.14221/ajte.2012v37n7.4 [ Links ]

Uysal HH 2010. The role of grammar and error correction in teaching languages to young learners. In B Haznedar & HH Uysal (eds). Handbook for teaching foreign languages to young learners in primary schools. Ankara: Ani Publications. [ Links ]

Walker R (ed.) 1985. Applied qualitative research. Brookfield, VT: Gower. [ Links ]

White L 1987. Against comprehensible input: the input hypothesis and the development of second language competence. Applied Linguistics, 8(2):95-110. doi:10.1093/applin/8.2.95 [ Links ]

White L, Spada N, Lightbown P & Ranta L 1991. Input enhancement and L2 question formation. Applied Linguistics, 12(4):416-432. doi: 10.1093/applin/12.4.416 [ Links ]

Wright R 1996. A study of the acquisition of verbs of motion by grade 4/5 early French immersion students. Canadian Modern Language Review, 53:257-280. [ Links ]

Zucker C 2007. Teaching grammar in the foreign language classroom: teacher beliefs, teacher practices, and current research. In B Johnston & K Walls (eds). Voice and Vision in Language Teacher Education: Selected papers from the 4th International conference on Language teacher education. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]