Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.33 n.4 Pretoria Jan. 2013

Masihambisane, lessons learnt using participatory indigenous knowledge research approaches in a school-based collaborative project of the Eastern Cape

Thenjiwe MeyiwaI; Tebello LetsekhaII; Lisa WiebesiekIII

IHuman Sciences Research Council; University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. tmeyiwa@hsrc.ac.za

IIHuman Sciences Research Council; Rhodes University, Grahamstown

IIIHuman Sciences Research Council; University of KwaZulu-Natal

ABSTRACT

Masihambisane is an Nguni word, loosely meaning "let us walk the path together". The symbolic act of walking together is conceptually at the heart of a funded1 research project conducted in rural schools of Cofimvaba in the Eastern Cape. The project focuses on promoting the direct participation of teachers in planning, researching, and developing learning and teaching materials (LTSMs), with a view to aligning these materials with indigenous and local knowledge. In this paper we make explicit our learning, and the manner in which we carried out the collaborated research activities, using the Reflect process.

Keywords: Cofimvaba; Eastern Cape; indigenous knowledge; participatory action research; Reflect processes.

Introduction

The role of indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) in enhancing and contextualizing education was recognized by United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1978 at a meeting of one of the United Nations' (UN) agencies, the World Intellectual Property Organisation (Zazu, 2008). Against this background, research, for example, by Corsiglia and Snively (2001), Emeagwali (2003) and Letsekha, Wiebesiek-Pienaar and Meyiwa (2013), has focused on the documentation and study of indigenous knowledge, in order to benefit school curricula. These studies have expressed the value of IKS and the need for educational processes to be properly contextualized within local knowledge and languages. Letsekha et al. (2013) argue that in the South African context, such a status quo would lead to linkages between the schools or education systems, the home, and the wider community of the schools. As a result of the country's socio-political history, which has been unequal, and has excluded oral and undocumented cultural heritages, the inclusion of the IKS into the school curriculum was proposed (Department of Education (DoE), 2002).

South Africa's transition into democracy occurred in 1994. Following this transition there has been a number of changes to the schooling system. Chisholm (2004) reasons that these were attempts to overcome the legacy of apartheid; they were introduced in order to improve educational access, equity and quality. Following these changes, school learners have had to learn in the context of the Revised National Curriculum Statement (RCNS) from Grades R to 9, published in 2002; and the National Curriculum Statement (NCS) from Grades 10 to 12, published in 2003. The RNCS and NCS prescribe what learners should know and be able to do, while the Assessment Standards for each grade describe the minimum level, depth, and breadth of what should be learned in each learning area (Gardiner, 2008). Currently, school learners learn in the context of the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) which was implemented for the first time in 2012. CAPS does not replace the NCS, however, it provides guidelines for each grade and subject in relation to the content to be taught. According to the Department of Basic Education (DBE, 2011:3), the CAPS is a "single, comprehensive, and concise policy document, which will replace the current Subject and Learning Area Programme Guidelines and Subject Assessment Guidelines for all the subjects listed in the National Curriculum Statement Grades R -12".

In its policy documents, the DBE argues that the National Curriculum has been designed this way so as to ensure that it is flexible, and has the ability to be adapted to local conditions and needs at school level (www.education.gov.za). In turn, the DBE expects these curricula to be interpreted and implemented differently in diverse contexts. Although this is the case, schools in so-called "rural" areas are still unable to take advantage of the opportunities created by the National Curriculum, owing to limited resources available to them. Given South Africa's political past the terms 'rural' and 'urban' have a complicated history. Recent studies have drawn attention to the way in which knowledge of classroom teaching styles is organized, determining the atmosphere of the school, and the way in which learners think about class and status (Hays, 2002; Wiebesiek, Letsekha, Meyiwa & Feni, 2013). In the South African context, IKS constitutes part of a challenge to the manner in which formal thinking and conceptualization has occurred. Advocates of IKS maintain that its study has profound educational and ethical relevance. This recognition led to a number of studies being conducted within southern Africa (e.g. Emeagwali, 2003; Zazu, 2008; Mokhele, 2012). However, much of this research did not translate into practical curriculum processes, leaving educational processes de-contextualized.

Employing participatory action research, we sought to better understand the Cofimvaba community, and schools that were used as research sites - to work, in particular with practising teachers, towards improving the school curriculum. As both participants and researchers on the project, we engaged in reflexive enquiry, using Reflect processes. Reflect is "an innovative approach to adult learning and social change, which fuses the theories of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire with participatory methodologies" (Reflect Action, 2009b:1). It is a process which promotes a collaborative and community-based approach to research, hence our reference to the Nguni word masihambisane, which refers to the IKS principle of working together. We embarked on this path collaboratively, working with teachers and indigenous knowledge (IK) holders, who served as community-based researchers. Equally informed by indigenous knowledge systems approaches, through this project, we employed values of collective inquiry and experimentation, grounded in experience and socio-cultural history of the Cofimvaba community.

Cofimvaba socio-cultural and economic contextual background

Of recent years, African countries, through the African Union and regional commissions, have held heightened debates on finding a means of poverty alleviation, and of improving the quality of education within the continent. Some of the debates have suggested that it is crucial to draw from indigenous and local knowledge in order to strengthen these developmental imperatives, especially in rural communities, where most households are female-headed (International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), n.d.; Olatokum & Ayanbode, 2009).

Indigenous rural men and women have greatly contributed to the development of local communities. The Eastern Cape Province, and in particular the Cofimvaba community, is predominantly rural. It is characterized by high levels of poverty and unemployment, as a result of critical skills shortage, small-scale subsistence farming, the reliance on indigenous plants, food insecurity, and diseases such as Human Immunosuppresive Virus (HIV) and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). The region is also confronted by natural disasters such as drought, erosion, and floods. A lack of emergency plans in such situations warrants high-level intervention. Cofimvaba indigenous people are reported to have influenced discussions and community meetings held a propos the need to resuscitate the Cofimvaba environmental wealth and education system, employing indigenous perspectives (2012 interviews). They have worked together as a collective, mostly in the form of a variety of women's organizations, for the purpose of securing food production and for collecting funds. The communal village networks have led to some being able to take their children to institutions of higher learning, as well as helping to build each other's houses. Concerns have been expressed over the possibility of a continuation of such achievements, owing to the decline of the quality of the pass rate in their schools. The Eastern Cape had the poorest performance in the 2011 final senior secondary results; with five of the poorest-performing districts being in the province.

For the purposes of this proj ect, 'indigenous people' refers to people, schooled or unschooled - who espouse, preserve, and live out a certain degree of Xhosa/ Eastern Cape Nguni indigenous life. Cofimvaba is one of the two main towns within Intsika Yethu Local Municipality (IYLM), of the Chris Hani District Municipality of the Eastern Cape. A number of households in Cofimvaba live in abject poverty (IYLM, 2011). Within the households, many are women. They are unemployed, or they participate in informal employment; however, they manage to provide for their families. As with many rural women, Cofimvaba women are primarily responsible for caring for the elderly and the young; for household food security; for gathering firewood; as well as for earning an income. A preliminary study (2012) at Cofimvaba found that the main source of their strength is IKS. Also, women were found to be the primary brokers of IKS. Most respondents who participated in the study made reference to these women as "sources of information" for the indigenous knowledge IK data which they shared with us. They were equally referred to as "pillars of strength" - who ensure that life in Cofimvaba is lived out in the best possible way.

Entitled "Promoting and learning from Cofimvaba community's indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) so as to benefit the school curriculum", the research project to which we refer is aimed at developing teaching and learning materials for use in the classroom. Foremost, in order to realize this aim, the project seeks to find ways of identifying and making use of local and indigenous knowledge which would benefit the school curriculum, and in turn forge links between the school and the wider community. Since the inception of the project, we have come across vast amounts of accumulated knowledge, traditional skills, and technology of Cofimvaba's indigenous women, which goes undocumented.

Research questions and objectives

Against the background outlined above, the following broad research questions were formulated for the research project:

1. What specific indigenous knowledge systems' content could be included in a school curriculum?

2. How could the Cofimvaba indigenous and local knowledge be used in strengthening and better contextualizing the curriculum?

With these research questions in mind, we set proj ect obj ectives, persuaded by Reason and Bradbury's (2008) assertion that effective participatory research should aim for rural communities and their diverse members to be actively involved in the identification of development problems; and should search for solutions, promotion, and the implementation of useful knowledge. Hence, the following objectives:

- Document and study the Cofimvaba's IKS, in order to deepen understanding of the contemporary culture of a community with a rich traditional cultural heritage;

- Study the Cofimvaba community, in order to explore the activities and IK-informed meanings which respondents give to the current culture of the community;

- Establish the way in which school-based respondents relate their community day-to-day activities to school activities; and

- Forge linkages between the school, the home, and the wider community.

We used the above framework, which equally sets the stage for a kind of research that is participatory in nature, as it inherently depends on participatory communication. It allowed for desirable flows of information, which happen at and between various levels of the Cofimvaba community, i.e. horizontally, and vertically.

Conceptual framework and methodology

We received consent and ethical clearance for the proj ect from Cofimvaba's individual research participants; traditional and political leadership structures; district and provincial educational authorities; and from the Human Sciences Research Council's Ethics Research Committee.

The project is qualitative in nature; it adopts participatory action-research methodologies. Seeking to understand Cofimvaba community's IKS, as discussed in the above section, and with attempts at integrating it into the school curriculum, we work collaboratively and reflectively with teachers. Reason and Bradbury (2008:1) argue that the essence of participatory research is a process comprising groups that work together as communities of inquiry, wherein "action evolves and addresses questions and issues that are significant for those who participate as co-researchers". Similarly, Chevalier and Buckles (2013) point out that participatory action researchers and practitioners ensure that in their planning and execution of this type of research, three basic aspects are involved, that is, participation (life in society and democracy), action (engagement with experience and history), and research (soundness of thought, and the growth of knowledge). We were informed by this paradigm in our research approaches, as well as influenced by the fact that "action unites, organically, with research" (Rahman, 2008:49). Included in our practice was the collective process of self-investigation, wherein, as researchers and teachers, we investigated, evaluated, and reflected on our research processes. There was variation in the manner in which each component was embarked upon, relative to the need that research participants had expressed. This, of course, bears evidence to the fact that participatory action research approaches are not linear and monolithic in their outlook, rather, they are pluralistic, with a view to generating knowledge and bringing about change (Chambers, 1994; Shulman, 1986; Camic & Joas, 2003). Of significance is Chambers' (1994:1253) caution that, more importantly in rural contexts, practitioners and researchers should guard against rushing the research processes; however, equally prioritizing "being self-critically aware".

Furthermore, the Reflect process is used in workshops with teachers. This approach is ideal for adult learning where there is a need for a change, or a review of past and current activities. In developing materials for teaching and learning, it encourages discussion that takes cognizance of the experiences and knowledge teachers have acquired as on-the-job practitioners. Thus, teachers develop their own learning and teaching materials, basing their analyses and choices of what should best be included in the materials, on lived experiences. The Reflect approach builds on what people know, rather than concentrates on simply training people on what they do not know. This respect for people's own knowledge and experiences is a crucial element for the Reflect approach to learning - an approach that is akin to indigenous knowledge systems and participatory methodologies. The approach of taking into consideration all these facets ensures that people's voices are heard, thereby minimizing power dyna- mics often inherent in research processes which have a significant element of intervention. In the next section we discuss values integral to Reflect, as well as reasons for adopting this approach.

The Reflect and indigenous knowledge systems' research approach

Reflect "was developed in the 1990s through pilot proj ects in Bangladesh, Uganda and El Salvador; it is now used by over 500 organisations in over 70 countries worldwide" (Reflect Action, 2009b:1). We adopt this participatory approach, encouraged by the success it has brought for many projects conducted in rural contexts of the countries of the south, wherein effective communication and ownership has been achieved. A stance held by Reflect, is that the less vocal and less connected groups such as rural communities, can best be heard through a form of participation addressing their needs by being led by the manner in which the communities themselves express such needs. Hence, effective communication is viewed, first and foremost, as including them in the discussions, decisions, and planning of proposed interventions. For Reflect, effective communication in development processes "cannot be one-way because it requires feedback and continuous exchange of information between partners and interest groups, communities and official entities" (Reflect action, 2009b).

At the proposal stage of the project, we engaged with the Cofimvaba education district officials, school principals, a few teachers, and various leadership structures. Their input on what was envisaged for the project was incorporated into the proposal, including the adapting of a model of integrating IKS into the school curriculum that had worked well in rural schools elsewhere within South Africa. Convinced that this route would yield ideal results, we conducted workshops, seeking the participation of teachers of Cofimvaba. However, during the first few months of implementing the project, it transpired that teacher participation in the discussions was less than ideal. It became apparent that the earlier path taken, thought to have been inclusive, was not inclusive enough. The research team was compelled to revise its approach, which included planning anew, and concentrating on the Foundation Phase only for the next two school terms, that is for about six months. It was during the "second phase of planning" that the research team embraced the Reflect principles, beyond just being participatory in our approach. It was also during this time that we brought on board a young researcher who lives in the vicinity of the research sites, and specializes in isiXhosa; the people of Cofimvaba being primarily first-language isiXhosa speakers. This bears evidence to Warren, Slikkerveer and Brokensha's (1995) assertion, that modes of communication and expectations are influenced by social, educational and cultural differences. Since then, we have come to appreciate that decisions and planning of rural educational development require effective and proper communication, especially with groups who are expected to implement lessons learnt. Hence, proper participation, with appropriate people, creates better understanding, improved connectivity, and commitment (Shotter, 2012).

Furthermore, we have realized that using Reflect approaches has assisted all teams working closely on the project; both the teachers and the research team, in focusing better on the purpose of producing materials that speak to the context of the schools. In addition, embarking on constant reflection has led to a shortened time between creating knowledge, and integrating knowledge into teaching and learning materials.

The journey to developing the teaching and learning materials began at different times for each of the contributors to this paper. Because team members joined the proj ect at different times, this served as an opportunity for conducting more reflecting, because, in explaining what the project was about, and its processes, we revisited, and found the process a form of participatory research. Subsequently, we have adopted a policy of reflecting on every activity on which we embark, by critically reviewing preceding activities; and posing critical questions, in order to improve on future activities. This outlook is in line with the IKS research approach to research, wherein researchers periodically assess their activities, as well as their engagement with people with whom they work. It is based on the principle of ensuring that their cultural heritage is valued. In developing materials and policies which benefit rural people, and are sensitive to indigenous and local knowledge, IKS research approach contends that our individual and shared human cultural legacies are a great resource. The cultural traditions should serve as a source in finding values, methods, practices and insights into how to achieve a harmonious relationship, both with nature, local context, and within human civilization (Crawhall, 2006, 2008; Weber, 1994). Persuaded by these scholars' standpoints in this regard, we have equally had self-reflexive sessions within the research team, as well as with the teachers.

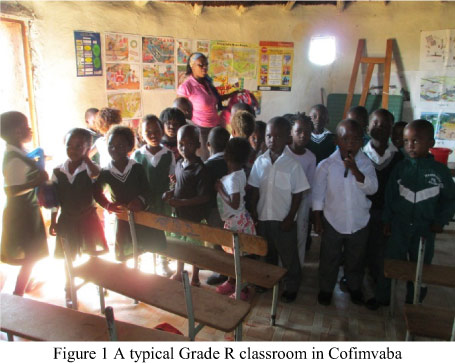

The schools and teachers invited to participate in the proj ect were initially excited about the concept. They intimated that they found the core objectives of the project close to their hearts, as they related to the manner in which they were raised; and that IKS and its relevance was evident in many households within the community. Much of the excitement about the project also came because it sought to link the school and home environment. The integration of local and indigenous knowledge meant that even parents with low levels of schooling could be involved in their children's education. The teachers themselves reflected on a number of occasions that they would like to use more context-specific and relevant examples, methods and tools in the classroom. Figure 1 is an image of one of the Cofimvaba classrooms, showing materials used by a Foundation Phase classroom. At an earlier meeting with the teachers, an example of a reflection we found relevant was teaching about a beach scene, when many of the learners had not seen the beach before.

Discussion and lessons learnt

Effective participatory methods require much time, training and patience, because the approaches are at most influenced by communication that is bottom-up, rather than hierarchical. Now, in the second year of the proj ect, we are convinced that our relationship with the teachers and community of Cofimvaba has improved; trust has been established. When the teachers realized our commitment to listen to them earnestly, they committed unreservedly to investing their time and intellectual capital in the project. Field researchers from Cofimvaba, both from the community and schools, were trained in basic research practices, with a focus on collecting data, and dealing with research participants, in a manner that is participatory, sensitive, and respectful of research participants. In turn, they have collected data on totem animals, and Cofimvaba villages' cultural heritages, including agricultural practices indigenous to Cofimvaba. Henceforth, the research team has engaged with teachers, principals of schools, and district officials in various workshops, in exploring:

- The way in which the teachers, learners and School Governing Bodies relate to their environment;

- The way in which teachers, learners and School Governing Bodies in the context of Cofimvaba experience and use the curriculum and teaching tools;

- The learning areas in which teachers, learners, and School Governing Bodies feel they would like more support;

- The way in which teachers, learners and School Governing Bodies envisage using IK in enriching and contextualizing the school curriculum in Cofimvaba; and

- The kinds of indigenous knowledge which is available, used, and valued by the community; e.g. contemporary ceremonies and rituals performed, foods that are preferred, etc.

We are in the process of developing teaching and learning materials informed by the data and conversations held with various Cofimvaba people, before finalizing and mass printing the materials we plan to share, "quality assuring" them with these groups. The four images below illustrate some of the examples of items used in the Foundation Phase of the Cofimvaba classrooms on one hand (see Figures 2 and 3), and on the other hand, what the teachers have indicated should form part of the content of the materials (Figures 4 and 5). The second set of images recognizes local and indigenous knowledge systems; and ensures that the content is shaped by local contexts to which learners can easily relate.

Knowledge, and in turn content which finds its way into school books, is fluid and complex, however, it is essential that it is shaped by local contexts. The people of Cofimvaba, from whom IK data was collected, and learners and teachers who equally live out IK, are assuredly in love with their cultural heritage. However, at first it was not easy persuading them that their 'knowledge'' was rich enough to make its way into the school curriculum and workbooks. It is to this end that Crawhall (2008:3) submits that:

it is a major challenge to ensure the recognition of local and indigenous African knowledge systems which have for one reason or another been marginalised or even damaged...Africa's cultural heritage is oral and undocumented, stigmatised by European ideas of the primacy of the written word.

Beyond working towards developing and adapting materials to specific social and cultural environments, forms of communication are crucial (Hays, 2002; Quarry & Ramirez, 2009). Quarry and Ramirez (2009:11) are emphatic on this point, referring to communication as a significant participatory approach of "listening before telling". As we progress, conducting research on this proj ect, it becomes more apparent that we need to further strengthen our participatory tools and forms, in engaging with the community. The need for displaying sensitive regard for research participants with marginalized heritages has long been recognized by scholars from various backgrounds, within and beyond the African continent. For instance, Mazrui (1978), African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (2005) and Whitehead and McNiff (2006), mention that communication behaviour has to be sensibly handled; and that it is critical to arrange communication situations in a way that works towards building trust, making people feel confident in speaking about their deepest concerns. This becomes more crucial in rural contexts, where many people are vulnerable groups, and are perceived to be of a lower social status. Because we have made use of participatory research methodologies, which have employed related IKS and Reflect approaches, we are confident that the collaborative research has benefited from relations and connections created between the research team, indigenous holders, and schools of Cofimvaba. In demonstrating qualitative evidence of the impact of these methodologies, the project discussed in this paper, that is, "Promoting and learning from the Cofimvaba's indigenous knowledge systems to benefit the curriculum" demonstrates that participatory approaches are effective.

The fact that local knowledge is valued by all, and is beginning to 'see its way into the classroom' has further strengthened our relations, and led community-based stakeholders to take a more active role and greater responsibility for the development of context-relevant teaching and learning materials (Wiebesiek et al., 2013).

Projects using such approaches often lack baseline data and clear monitoring and evaluation procedures, which would immediately demonstrate both qualitative and quantitative impact. However, their long-term benefits, which may only be realized long after the end of the official project and intervention, may have a momentous effect, owing to active involvement and empowerment received during the life of the project.

As we progress with the project, which is in its second year of implementation, we have learnt significant lessons that could be summarized as given below. Strategies for improving participation in the communication process with people that are mostly marginalized should include:

- Carefully planned participatory methodologies which assess beforehand, and are aware of differences existing among stakeholders and related different modes of communication;

- Involving senior education officials as stakeholders from the very beginning, when introducing participatory approaches, in better understanding and supporting of the project;

- Adaptation of participatory methodologies to local situations, taking into cognizance the importance of giving voice to vulnerable groups;

- Material development incorporating exposure and practise in the actual research processes, in order to create essential honesty, and in turn to develop the necessary skills;

- Capacity development for facilitating the collection of data and continued participatory communication;

- Working closely with the beneficiaries, when introducing and/or suggesting new approaches to enhancing school curriculum; and

- Being flexible and open-minded in collaborative research and participation, without compromising the broad objectives of the development process.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper has been to provide an insight into a study that includes multiple partners, and that sets out to use participatory methodologies. Collaborative research among groups with various skills and education levels can lead to participatory manipulation, where groups perceived to possess better skills and higher social status can dominate those perceived to be weaker. We also acknowledge that, even with participatory methodologies, manipulation and power relations should be guarded against, as they can stifle progress. Drawing from the principles of Reflect, we acknowledge that being consciously sensitive to power is crucial to maximizing the use of such methods for truthfully empowering targeted beneficiaries. It is "only with a deep awareness of power at all times and at all levels that we may use participatory processes effectively" (Reflect Action, 2009a). Drawing on the principles of indigenous knowledge systems, we also acknowledge that it is crucial to respect local people's knowledge and experience. Such regard may only be demonstrated by actively involving them in "processes that seek to benefit them" (Meyiwa & Ngubentombi, 2010:128).

As demonstrated in the above discussion, participatory approaches may be slower, and somehow 'messy' at starting points, however, we have found that they can be rewarding for all stakeholders. Sustainability is also a possibility. The benefit can be more rewarding if the processes are geared towards capacitating beneficiaries, and in turn maximizing possibilities of more meaningful or useful results; with longer-lasting effects, as well as a sense of ownership. Although the study is in its second year, we believe that the path we have walked thus far can provide useful lessons for researchers and scholars involved in educational interventions, particularly in rural contexts. As we have been implementing the project, we have adopted a dynamic approach to planning and activities, allowing the project to adapt to the context, as with our learning from it. The Reflect approach heightens the conducting of participatory research, as a need for materials that address challenges experienced, using local knowledge often gained over generations of observations. The discussion of this paper has demonstrated the benefit of creating contextual knowledge and materials, in listening and acting upon the voices of the people who will use such materials. Consequently, Reflect was instrumental in ensuring ownership of the materials, an attitude that maximizes sustainability of interventions.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding for the project by the Department of Science and Technology, National Research Foundation, and Human Sciences Research Council. We recognise the active participation and assistance of the following community-based researchers, indigenous knowledge bearers, and teachers: Yolisa Madolo, Bukiwe Feni, Thembile Sikweqe, Bandlakazi Mdlokolo, Gloria Mateta and Nomlindelo Jonas.

Note

1 This paper is drawn from a three-year (2012-2014) research project sponsored by the South African National Research Foundation (NRF).

References

African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights 2005. Report of the African Commission's working group of experts on indigenous populations / communities. Copenhagen: ACHPR and IWGIA. Available at http://www.iwgia.org/iwgia_files_publications_files/African_Commission_book.pdf. Accessed 9 October 2013. [ Links ]

Camic C & Joas H (eds) 2003. The dialogical turn: New roles for sociology in the postdisciplinary age. New York: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Chambers C 1994. Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): Analysis of experience. World Development, 22:1253-1268. Available at https://entwicklungspolitik.uni-hohenheim.de/uploads/media/Day_4_-_Reading_text_6.pdf. Accessed 9 October 2013. [ Links ]

Chevalier JM & Buckles DJ 2013. Participatory action research theory and methods for engaged Inquiry. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Chisholm L 2004. The quality ofprimary education in South Africa. Background paper prepared for Education for All Global Monitoring Report, 2005. Available at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001466/146636e.pdf. Accessed 18 April 2013. [ Links ]

Corsiglia J & Snively G 2001. Rejoinder: Infusing indigenous science into western modern science for a sustainable future. Science Education, 85:82-86. doi: 10.1002/1098-237X(200101)85:1<82::AID-SCE11>3.0.CO;2-Q [ Links ]

Crawhall N 2006. MDGs, globalisation and indigenous peoples in Africa. In MW Jensen (ed.). Indigenous Affairs. Copenhagen: IWGIA. Available at http://www.iwgia.org/iwgia_files_publications_files/IA_1-2006.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2012. [ Links ]

Crawhall N 2008. Heritage education for sustainable development: Dialogue with indigenous communities in Africa. Paris: United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Available at http://www.ipacc.org.za/uploads/docs/090505b_ESD_composite_repor_Africa08_final.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2013. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE) 2002. Revised national curriculum statement. Pretoria. Available at http://us-cdn.creamermedia.co.za/assets/articles/attachments/00208_curriculum.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2013. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2011. National curriculum statement grades R-9: Curriculum and assessment policy statement. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Emeagwali G 2003. African Indigenous Knowledge Systems (AIK): Implications for the curriculum. In T Falola (ed.). Ghana in Africa and the World: Essays in Honor of Adu Boahen. New Jersey: Africa World Press. [ Links ]

Foundation Phase workbooks 2012 & 2013. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Gardiner M 2008. Education in rural areas. Issues in Education Policy, 4. Johannesburg: Centre for Education Policy Development. Available at http://www.3rs.org.za/index.php?module=Pagesetter&type=file&iunc=get&tid=2&fid=document& pid=7. Accessed 9 October 2013. [ Links ]

Hays J 2002. "We should learn as we go ahead": Finding the way forward for the Nyae Nyae village schools project. Perspectives in Education, 20:123-139. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/persed/persed_v20_n1_a10.pdf. Accessed 9 October 2013. [ Links ]

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) (n.d.). Enhancing the role of indigenous women in sustainable development: IFAD experience with indigenous women in Latin America and Asia. Available at http://www.ifad.org/english/indigenous/pub/documents/indigenouswomenReport.pdf. Accessed 21 September 2012. [ Links ]

Intsika Yethu Local Municipality 2011. Integrated Development Plan Report. [ Links ]

Letsekha T, Wiebesiek-Pienaar L & Meyiwa T 2013. The development of context-relevant teaching tools using local and indigenous knowledge. Paper presented at the 5th World Conference on Educational Sciences, Italy. Available at http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/research-outputs/view/6352. Accessed 9 October 2013. [ Links ]

Mazrui A 1978. Political values and the educated class in Africa. Berkeley CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Meyiwa T & Ngubentombi S 2010. Reflecting on research practices and indigenous community benefits for poverty alleviation purposes in the eastern seaboard region of South Africa. Indilinga: African journal of indigenous knowledge systems, 9:127-137. [ Links ]

Mokhele PR 2012. Dealing with the challenges of curriculum implementation: Lessons from rural secondary schools. African Journal of Governance & Development, 1:47-65. [ Links ]

Olatokun Wole M & Ayanbode OF 2009. Use of indigenous knowledge by women in a Nigerian rural community. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, 8:287-295. Available at http://nopr.niscair.res.in/bitstream/123456789/3968/1/IJTK%208%282%29%20287-295.pdf. Accessed 9 October 2013. [ Links ]

Quarry W & Ramirez R 2009. Communications for another development: Listening before telling. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Rahman Md A 2008. Some trends in the praxis of participatory action research. In P Reason & H Bradbury (eds). The Sage handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. Sage: London. [ Links ]

Reason P & Bradbury H (eds) 2008. The Sage handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (2nd ed). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Reflect Action 2009a. Participatory tools. Available at http://www.reflect-action.org/how. Accessed 9 October 2013. [ Links ]

Reflect Action 2009b. Reflect. Available at http://www.reflect-action.org. Accessed 12 April 2013. [ Links ]

Shotter J 2012. Situated dialogic action research disclosing "beginnings" for innovative change in organizations. Organizational research methods, 13:268-285. doi: 10.1177/1094428109340347 [ Links ]

Shulman LS 1986. Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15:4-14. [ Links ]

Warren DM, Slikkerveer LJ & Brokensha D (eds) 1995. The cultural dimension of development: Indigenous knowledge systems. London: Intermediate Technology Publications. [ Links ]

Weber P 1994. Net loss: Fish, jobs and the marine environment (Worldwatch paper 120). Washington, DC: Worldwatch Institute. [ Links ]

Whitehead J & McNiff J 2006. Action Research Living Theory. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Wiebesiek L, Letsekha T, Meyiwa T & Feni B 2013. Pre-service and in-service Training, Indigenous Knowledge and Foundation Phase Teachers' Experiences in the South African Classroom. Paper presented at XI Annual International Conference of the Bulgarian Comparative Education Society, Bulgaria. [ Links ]

Worksheetfun.com 2013. Worksheets. Available at www.worksheetfun.com. Accessed 02 April 2013. [ Links ]

Zazu C 2008. Exploring opportunities and challenges for achieving the integration of indigenous knowledge systems into environmental education processes: A case study of the Sebakwe Environmental Education programme (SEEP) in Zimbabwe". MEd dissertation. Grahamstown: Rhodes University. Available at http://eprints.ru.ac.za/1267/1/Zazu-MEd-thesis.pdf. Accessed 9 October 2013. [ Links ]