Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.33 no.3 Pretoria ene. 2013

New spaces for researching postgraduate Education research in South Africa

Daisy PillayI; Jenni KarlssonII

ISchool of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Edgewood Campus, South Africa. Pillaygv@ukzn.ac.za

IISchool of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Edgewood Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Universities in South Africa during apartheid reflected the racialised politics of the period. This gave rise to divisive descriptors such as 'historically white/black'; 'English/Afrikaans-speaking' institutions and 'Bantustan' universities. These descriptors signal a hierarchy of social status and state funding. We start by explaining how these apartheid-era institutional arrangements formed socially unjust 'silos' around postgraduate Education researchers and their research. Against this backdrop, we describe a project that surveyed postgraduate Education research at 23 institutions in South Africa between 1995 and 2004 - the first decade of democracy. The products of the survey constitute two spaces. First, there is the physical archive of dissertations and theses from the higher education institutions. This space disrupts the historical differences and physical distances, bringing together the postgraduate Education research of that period. The second space is the electronic bibliographic database of the archive. It is an abstract space that defies traditional shelving arrangements. We argue that this national project broke down the apartheid-era silos that separated the postgraduate Education research of the different higher education institutions in South Africa. In this article we propose that a third space manifests when a researcher works with the project's archive and/or database. It is a space of lived experience. In the interactive moment and space, when the researcher connects with the archive or database, there is the possibility of the researcher generating new understandings and ideas of/about Education research. Although the project described in this article has ended, we found that in the third space of the interactive experienced moment fresh questions about the knowledge produced by postgraduate Education researchers in South Africa, at the critical historical moment of the first decade of democracy, were made possible.

Keywords: archive; database; knowledge production; postgraduate research; spatial theory

Introduction

Postgraduate Education research in South African higher education (HE) institutions since 1994 continues to be shaped by race, gender, institutional specificities, disciplinary field and philosophical approach. These are the findings generated through the Project on Postgraduate Education Research (PPER), which focused on masters' and doctoral Education degrees undertaken in the period 1995-2004 at 20 higher education institutions in South Africa. The first phase, funded by the Ford Foundation, involved a lengthy process of developing a database and an archive that covered 11 higher education institutions. A year later, South Africa's National Research Foundation (NRF) became involved in the project and this led to the project's expansion to a national level with 20 out of 23 higher education institutions identified as contributors.

For their survey the PPER researchers visited 20 higher education institutions and photocopied and bound key sections of education theses and dissertations found in the libraries and departments of those institutions. In the Project these collected documents were housed together in a room known as the 'archive' and the contents of the documents were catalogued and classified electronically to form a bibliographic database. In this article we use Lefebvre's (1991) theory of space to reflect critically on three spaces which emerged over the course of the Project: the archive of physical documents, its virtual counterpart of the database, and the lived space when researchers use either the archive or database, or both.

A key driver that led to the start of the PPER was South Africa's change of political system from apartheid to democracy in 1994. Previously the higher education sector was dictated largely by the geo-political imagination of apartheid planners (Department of Education, 1999). The literature suggests that the compelling need for the transformation of the higher educational landscape lies in the history of the institutions and the way this landscape reflects the racialised politics of the apartheid past (see Jansen, 2003). Scholars researching this sector (Cloete, Fehnel, Maassen, Moja, Perold & Gibbon, 2002; Chisholm, 2004, Jansen, Herman, Matentjie, Morake, Pillay, Sehoole & Weber, 2007) use descriptors to distinguish and signal the histories, giving rise to terms such as 'historically-white/black', 'English/Afrikaans-speaking' institutions and 'Bantustan' universities (National Education Policy Investigation, 1993). These descriptors signal a hierarchy of social status. The way higher education institutions were founded; their communities and the social purpose for which they were intended - as well as their curricula and scope for funded research - are among the features that provided each institution with a particular identity and political and social position. The PPER researchers contend that these institutional arrangements since 1994 shape and continue to shape knowledge production in particular ways (see Bengesai, Goba & Karlsson, 2011; Goba, Balfour & Nkambule, 2011; Karlsson & Pillay, 2011; Madiya, Bengesai & Karlsson, 2011; Molefe, Bengesai, Davey, Goba, Lekena, Madiya & Nkambule, 2011; Moletsane & Madiya, 2011; Nkambule, Balfour, Pillay & Moletsane, 2011; Pillay & Balfour, 2011; Rule, 2011; Rule, Davey & Balfour, 2011).

In this article we argue that the work of the Project itself broke down the silos that separated postgraduate Education research produced at the different higher education institutions. After presenting a brief historical context of higher education in South Africa and the PPER, we draw on Lefebvre's (1991) framework of social space to discuss the physical archive and the electronic database as two social products created by the Project. We complement this stance with the ideas articulated by Kuhlen (2003) on the universal human right of an information society and the principle of universal access to knowledge and information to be possible for present and future generations - for all people, at all times, in all places, and under fair conditions. More specifically, we consider how the database and archive, as products, may serve the right of citizens to gain information through publicly available resources (Kuhlen, 2003). We argue that the project's development of the physical archive space, its virtual counterpart in the bibliographic database, as well as the lived space when researchers connect with the archive and/or database, open up possibilities for privileging the critical role that intellectual endeavour plays in the critique of social transformation in South Africa. We show how the postgraduate scholars working in the Project achieved their potential through personal development, intellectual growth and change. The creation of these three spaces for interrogating postgraduate Education research offers fresh opportunities for questioning and challenging knowledge production within a reforming South African higher education landscapes and state funding. More importantly, they hold promise for the creation of fresh insights, meanings and understandings about postgraduate education research in South Africa, which would have been difficult without the Project's survey and development of the archive and database.

We (the authors) were academic members of the PPER research team and participated in the establishment of the archive and database. As the project's archive and database development work drew to a close in 2010 we began to use the PPER archive and database as researchers. We also supervised some of the student members of the team for -writing their dissertations and theses about a particular aspect of postgraduate education research in South Africa in the first decade after 1994. Over time we have gained the distance to reflect critically on the PPER's lived processes, products and achievements and have sought to gain a deeper understanding about the work and contribution of the project. Our intention in this article is to discuss our understanding about the spaces that derive from the project. Thus, data used for this article include the archive of collected postgraduate education research, the bibliographic database, notes from project meetings, publications, dissertations and theses written by members of the research team, as well as our remembered experiences. We presented early drafts at three conferences and have used the feedback and critique to refine and rework the article.

Historical context of higher education in South Africa

Apartheid-era institutional arrangements that entrenched racial division as well as language and cultural differences, created social isolation that came to characterise higher education institutions' postgraduate Education research as well as the researchers themselves (Bunting, 2002). This "silo-isation" (Bruch, 2003:34) of higher education separated white from black researchers; English- from Afrikaans-speaking researchers and urban from rural scholars and resulted in a legacy of injustice and inequality in many different ways.

This section lays out a brief history of the South African higher education landscape prior to 1994, fragmented as it was by apartheid ideology and the initiatives of the white regime. This conception of race and politics of race were responsible for shaping the higher education policy framework during this period. In his book, Knowledge and Power in South Africa: Critical Perspectives across the Disciplines (1991), Jansen uses Foucault's theory of power to explain how academics from historically white universities had power in South Africa during the apartheid era, and therefore had the means with which to produce knowledge. As a result, the corpus of knowledge produced through research in South African universities before the 1990s was the product of those put in positions of power by the apartheid system. The higher education system of that era was designed by white interests to preserve and entrench the segregated, hierarchical racial order that put white people in superior decision-making positions in society. Jansen (1991:1) refers to this sort of relationship when he says "knowledge is defined as codified social discourses which arise to both legitimate domination and mobilize resistance".

Using the apartheid logic of separate areas and institutions for different linguistic and racial groups, the government established (mostly) rural territories for various African ethnic groups, commonly referred to as 'Bantustan homelands', with self-governing powers. In these homelands and in the areas under white jurisdiction, the white authorities established universities, colleges, and technikons to provide African communities and homeland authorities with training programmes that produced, primarily, administrators and civil servants (Bunting, 2002).

Bunting (2002:81-84) classifies the institutions into eight categories that point to the form of knowledge production (university versus technikon); racialised authority and constituency; language (English versus Afrikaans) and geography (contact versus distance learning). The whites in South Africa, who constituted a racial minority, had exclusive access to 19 of the total number of higher education institutions, Indians had exclusive access to two, coloureds had access to two, and there were six for the exclusive use of Africans. The last did not include the seven institutions in the homeland territories. Across South Africa, the higher education landscape comprised a fragmented system of unequally-planned, -governed, and -funded institutions. This landscape, which constitutes an "outcome of social process and institutional guided actions of researchers" (Van Buuren & Edelenbos, 2004:289), yielded an uneven and geographically fragmented production of postgraduate research, which is evident from the PPER survey of postgraduate education research (Karlsson, Balfour, Moletsane & Pillay, 2009).

The policy ambitions of the South African government for higher education after 1994 included the combination or merger of institutions as an opportunity to reorient and revitalise higher education, in pursuit of important social and educational goals (Council for Higher Education [CHE], 2004:55). Thus research, covering the processes involved in reshaping higher education, encompasses the structural-political restructuring as well as the conceptualisation of knowledge generation itself (Jansen, 2003; Cloete et al., 2002).

In recognising the absence of a national overview of postgraduate Education research, in subject-content knowledge and methodological approaches, as well as about the profile of Education researchers, the PPER partly aimed to offset the tendency in education research in South Africa to "deal with the particular rather than the general in texts" (Balfour, Moletsane & Karlsson, 2011:202). Instead it sought to contribute to the South African grand narrative of knowledge generation by coupling "an account of the relationship of change over time and space between the micro-level of [higher education institutions] and the macro-level of policy and politics in South" (Balfour et al., 2011:202). In the next section we describe the Project.

The Project on Postgraduate Education Research (PPER)

To understand the trends and patterns in postgraduate Education research and the influence of institutional politico-histories on this research, a large team of academics and postgraduate students (of which the authors are academic members) embarked on a survey of postgraduate research in Education produced at all higher education institutions in South Africa from 1995 to 2004. This period covers the first decade of democracy. In this section we provide a description of the PPER and the methodology employed to generate the PPER survey.

At the time of initiating the Project in 2006, there was no existing overview of postgraduate Education research undertaken in South Africa, both in terms of methodological approaches and in terms of subject-content knowledge. The PPER team sought to understand the research agendas of institutions, academics and national research organisations and thus conceived of postgraduate Education research as a subset of the volumes of research produced by academics and professional researchers in the form of books, reports, articles and other media. Thus, the purpose of the Project was to establish the scaffolding to explore such research and thereby to begin to understand the emergent trends and patterns and what they imply about the higher education sector in South Africa at a particular historical moment in its growth as a developing democracy. The focus was on masters' and doctoral theses1 completed in the decade immediately following the 1994 democratic elections.

The PPER database was developed over two years by way of a layered survey methodology in which predominantly quantitative methods were used. At the start of the first phase the research team held a series of workshops in which the methodology was developed and data generating instruments were collectively formulated for the field visits to institutions. These comprised a guide for the copying of extracts from the relevant theses and dissertations, an interview schedule, and a questionnaire for supervisors.1

The fieldwork entailed sending three groups of student-researchers to visit institutions in the same geographical region. The duration of their stay at each institution varied depending on the volume of theses in the libraries they visited. The theses that were on the shelves at the time of data collection were selected by the year in which the research was conducted and making sure that these were for either a Masters' or doctoral degree in education. Certain sections of the theses, namely, the titles, abstracts, theoretical frameworks, methodologies and conclusion, were photocopied for analysis later. A total of 3,260 theses were photocopied during Phase 1.

A second round of data generation (Phase 2) included follow-up visits to some of the institutions from the first phase as well as the remaining higher education institutions in South Africa. From the second phase 516 more theses were added to the project's archive and database. By June 2010 over 3,776 theses (titles, abstracts, theoretical frameworks, methodologies, and conclusions), were gathered in the archive and captured on the database.

To develop as comprehensive and reliable a database as possible meant that in many instances student researchers returned to the various campus libraries around South Africa in order to obtain sections of theses missed during the original round of collection, or having to liaise with librarians telephonically, by email, or via inter-library loan, to retrieve such sections from a distance (see Balfour, Moletsane, Karl-sson, Pillay, Rule, Nkambule, Davey, Lekena, Molefe, Madiya, Bengesai & Goba, 2008).

Once each photocopied extract was bound and brought to the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), the student team commenced a process of cataloguing and classifying data for each thesis. The collected bound extracts and the electronic bibliographic catalogue constituted the archive and database respectively. To ensure a measure of uniformity for the classification and cataloguing process, control lists of terms and definitions were developed, for example concerning paradigms and methodology, on the basis of usage in scholarly literature and for local terms, those used in South Africa. The database was developed by the team of academics and postgraduate students, with the latter using the database of postgraduate research for their own degree-related research and construction of knowledge. Members of the research team also published several journal articles which involved analysis of the archived theses and the database.

To understand the nature and significance of the archive and database as 'social products' we now turn to the ideas of Henri Lefebvre (1991), the French social theorist, who wrote extensively about social space in the last century and conceptualised social relations as spatial practice.

The physical space, the abstract space, the 'lived' space

In writing about social interactions such as the collaborative research enterprise undertaken in the PPER work, we contend that Henri Lefebvre's (1991) work on social space provides a useful theoretical framework. Lefebvre (1991) asserts that social relations produce and yield a social space. The social space "facilitate[s] the exchange of material things and information" (Lefebvre, 1991:77) and has three dimensions of being a physically apprehended space; an imagined or conceived abstract space, and a lived space. Lefebvre's (1991) framework of these three dimensions is useful for conceptualising the spatiality of the PPER products and we discuss the products as spaces in the findings section.

In order to explain and analyse the form and function of social space, Lefebvre (1991) uses a scheme of three realms that are a centre, a periphery, and an intermediate realm in between. Lefebvre (1991) proposes that in the central realm, social space carries a public form with the function being to exercise and display power in various ways. For example in a university, the library and administration offices are often located in central and architecturally important buildings that take pride of place on the campus because those functions of storing and accessing knowledge (as scholarly research, ideas and debates) and institutional management are central to the core business of a university which is the pursuit and development of knowledge and understanding and imparting it to those who wish to learn. In places at the periphery Lefebvre (1991) sees forms being private and secluded (such as lecture and seminar rooms, and lecturers' offices), with the functions being more personal (such as group tuition, consultations, grading assignments and drafting texts). Lefebvre's (1991) intermediate passage has a transitional or transactional function that allows movement from the public realm to the private realm. For example, on a university campus there are many crossing roads, paths, walkways and passages for the human and vehicle traffic between the different buildings and offices located at the centre or periphery of the campus.

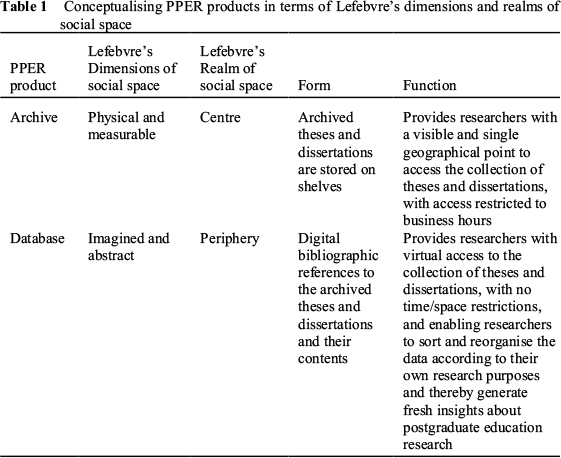

We find Lefebvre's (1991) scheme of the form and function of realms of social places useful for conceptualising the different natures of the Project archive and database as produced research spaces and we summarise this in Table 1. Through his framework, we gain fresh insights into the operation of the archive and database in a research context, and it sheds light on the domain of the researcher, who navigates between the spatial realms of the archive and the database.

In relation to the Project, the private and public realms are spaces that have different forms and serve varied functions for postgraduate researchers who are now able to have access to information and participate actively in developing their intellectual capacity for the greater public good (Said, 1994). In recognising that knowledge developed through research belongs to all of humanity (World Summit on the Information Society [WSIS], 2003; Drossou & Jensen, 2005), we also borrow from Christoph Bruch (2003) to show that access to information and the knowledge of earlier researchers and scholars under fair conditions and preserved in different media formats is a critical necessity. Having freedom to access the available research information stored in the physical archive and the electronic database, and the researcher's ability to choose is critical for understanding these spaces as being for researching postgraduate Education research in South Africa.

Findings

This section describes the physical archive and the electronic database as spaces where research records and information are captured and preserved for any further research purposes. We then explain these forms as public and private realms, respectively, and explain how postgraduate students and interested individuals can access these products for developing new insights and understandings about the body of knowledge in the theses and dissertations and share their findings through new publications. We envisage such findings to be written in as yet unseen and future theses and publications are a knowledge which will become available over time to future generations of researchers and in this way such shared intellectual knowledge and understandings will be for what Said (1994) referred to as the greater public good.

The PPER products as social spaces

Two products were created through the PPER research process: the archive and the database, as described above. We propose that they should be understood within Lefebvre's (1991) dimensions of social space and the framework for realms of real spaces, with the archive being the physical space that is within the public realm and the database being an abstract space that falls within the private realm. This theoretical perspective is useful for understanding and explaining the potential which the archive and database hold for researchers to have equitable access to information and knowledge stored in different formats. We see such products as providing opportunities for building inclusive knowledge communities. By inclusive knowledge communities we mean, for example, when students are included as researchers alongside their supervisors and other academics, and when researchers at distant, rural and under-resourced universities have the same access to data as researchers at well-resourced urban universities. In this section, we describe each PPER product, its spatial form and function. The last section proposes a third space that involves the researcher interacting with the product/s, and we offer an interpretation of its potential function.

The "archive space"

The archive (see Figure 1) is a physical room on the second floor of the main administration building on the Edgewood campus of the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Using Lefebvre's (1991) dimensions of space, we have classified the archive as a physical, measurable space that houses the extracts of theses gathered by the PPER team from the higher education institutions. The room occupied by the PPER archive was originally defined by the building's architect/s as a storeroom standing between two lecture rooms. The space continues to serve this function in that the archived theses are stored on shelves that fill the room from floor to ceiling. It is, however, also a work area for the librarian and data capturers to process the documents.

In the archive, the bound extracts of theses and dissertations are grouped by institution on shelves and arranged in numerical order according to a call number unique to each thesis or dissertation. The archive is a learning space in that researchers use the room to retrieve specific information. In this we agree with Georg Greve (2003) that knowledge represents the reservoir from which new knowledge is created.

Future researchers can visit the archive room in order to read and analyse each thesis, explore what was investigated, how the study was conducted and the argument, findings and conclusions of the author. Here, researchers from everywhere can converge to access and utilise the theses, and they can in real or virtual time/space debate and deliberate over how past postgraduate researchers conducted their studies and made sense of their data. These future researchers may be postgraduate students or established scholars and academics.

Christoph Bruch (2003:34) discusses the "de-silo-isation" of scientific knowledge in his article titled How Public is the Public Domain? He says:

Since science has a central role in the production of new knowledge, universal and open access to scientific knowledge, as well as equal opportunities for the creation and sharing of scientific knowledge, are crucial. Any research, especially research funded by public bodies, should enrich the public domain. This must be ensured by the promotion of efficient models for self-publication, open content contributions and other alternative models for the production, publication and sharing of scientific knowledge and the use of non-proprietary formats.

In disrupting the apartheid era 'silo-isation' of research, the PPER project, through its survey, brings together the dissertations and theses that were once scattered across South Africa in different university libraries into one physical space for the convenience of researchers. This de-silo-isation action was not merely a technical process of gathering, classifying and cataloguing. It was a deliberate political act that sought to reject the ways in which the apartheid higher education landscape set up divisions aligned to a racially prejudiced social hierarchy. However the archive and database continued to record that history in terms of retaining information about the institutional origins of each thesis. By bringing together the theses written during the first decade of democracy in South Africa into one place, researchers can access postgraduate education research, utilize it more easily than if the theses were scattered across many institutions.

Thus, the archive becomes a space for research that may yield new knowledge for a greater common good. Gathering the physical artefacts into one room breaks down the former institutional barriers of race, language and location. The room is a public space that showcases a decade of dissertations and theses where researchers can work shoulder to shoulder and make use of and have conversations about the theses taken from the shelves. As a social space, it offers a platform for different kinds of collaboration and dialogue. For example, in many university-based research projects students merely participate in the field to generate data and later to capture data. Student members of the PPER team, however, worked with academic members in small groups to use the archive for researching subsets of the body of postgraduate education research and co-publish their findings (see Madiya et al., 2011; Bengesai et al., 2011; Goba et al., 2011; Moletsane & Madiya, 2011; Rule et al., 2011; Nkambule et al., 2011). This process involved workshops in which the Project itself was debated and that dialogue led to the students reflecting on their shifting identification as students and researchers (see Molefe et al., 2011).

The electronic database

By contrast, the database product, in terms of Lefebvre's (1991) first triad of space, is an abstract space. It is abstract in the sense that the theses no longer have physical form; they are electronic representations referred to as entries or references, on an electronic computer-based library programme.3 In contrast to the physical archive, the database is a private space in that researchers can work individually in the privacy of their own homes, at a remote site. The database becomes the text - in contrast with the archive's texts which are the theses themselves. This is a different kind of dialogue from that which occurs in the archive room. This sophisticated retrieval system calls for knowledge and skills for managing information in a different format.

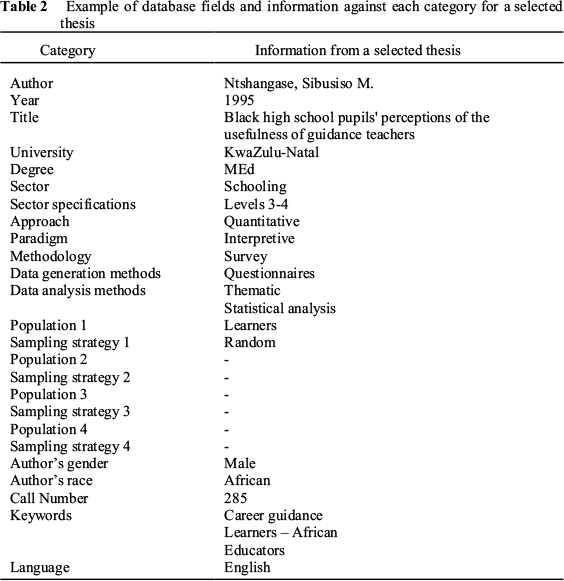

Initially the database was established using several sample theses to identify categories or discrete variables; for example, author, thesis title, university, type of degree, and subject. More categories were added at a later stage so that a total of 27 fields describe each thesis (see example in Table 2).

Tools such as standardized control lists were also devised for ensuring quality in stability, and consistency when capturing information within each category. These quality-related refinements sought to enhance the analytical potential of the database and consistency at a retrieval stage. Although the data are represented initially on the screen in columns according to standard bibliographic categories such as the author's name, thesis title, year of publication, institution of production, and so on, the database is searchable so that sub-sets of information about the theses can be sifted according to any keyword or term within any category, and saved as mini-databases that can be analysed more closely.

This abstract space (the electronic database) is also a learning space in that researchers may use it to access data in order to search, retrieve and sort sets of information about the theses and look for trends, patterns and correlations across categories. It allows for a personal, intimate transaction with the digitised data (thesis or groups of theses) so as to generate or produce new understandings and knowledge about postgraduate Education research. For example, a researcher wanting to know and understand how teacher education has been studied in the past might retrieve the list of masters' and doctoral theses on this topic and then sort them by degree and methodology. From this meta-level analysis that researcher may go on to theorise and write about teacher education research.

Accessing such an abstract space as the database requires the researcher to have computer competence and access to the appropriate technology. According to the Geneva Plan of Action (WSIS, 2003), people should be afforded opportunities to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge in order to articulate; become active part- icipants and benefit from the Information Society. However, once those basic requirements are met, a researcher's access to the database is not restricted by regimes such as library opening hours and geographic location, and it allows for more private engagement with the data in the (dis)comfort of any locale. As such, the personalised re-organisation of data and new computations using the database constitutes an intimate private encounter with the thesis or groups of theses that is not as easily observed as a researcher's reading of a thesis may be in the public space of the archive. In the next section, we offer an understanding of how this transaction works in the production of new knowledge.

"Potential Research": Lived and experienced Space

Part of the aim of the Project was to provide postgraduate students, their supervisors, academics, and researchers more broadly, a tool that would inform them about past postgraduate Education research undertaken at higher education institutions in South Africa, and help them to reflect on the degree of impact such work might have had, or continues to have (Balfour et al., 2011). Evidence that this aim was achieved can be found in students such as those discussed below, who have successfully completed their masters and doctoral degrees or whose work is in progress, based on their analysis of past postgraduate education research stored in the archive and database. In addition, the research team has presented numerous papers at conferences where the nature and work of the Project has been debated, and the team has authored 11 journal articles (see Karlsson et al., 2009; Bengesai et al., 2011; Goba et al., 2011; Karlsson & Pillay, 2011; Madiya et al., 2011; Molefe et al., 2011; Moletsane & Madiya, 2011; Nkambule et al., 2011; Pillay & Balfour, 2011; Rule, 2011; Rule et al., 2011). These articles critique postgraduate education research in South Africa on the basis of the contents of the archive and database as a whole or subsets within the archive and database.

The masters' and doctoral research studies are the lived spaces in and through which the researcher moves, between the public realm and the private realm of the electronic database and the researcher's internal intellectual thought processes. The transaction that occurs between the researcher and the stored research; the intellectual encounter and its consequence, produces knowledge.

The intellectual, according to Said (1994:11,13), refers to ... an individual endowed with the faculty for representing, embodying, articulating a message, a view, an attitude, philosophy or opinion to, as well as for, and a public. And this role has an edge to it ... someone whose place it is publicly to raise embarrassing questions, to confront orthodoxy and dogma ... who cannot easily be co-opted [...] [I]ntellectuals are individuals with a vocation for the art of representing, whether that is talking, writing, teaching, appearing on television. That vocation is important to the extent that it is publicly recognizable and involves both commitment and risk, boldness and vulnerability.

Arguably, the Project publicly raised an 'embarrassing question' when it initiated this national project and invited all of South Africa's higher education institutions to participate in it. By the project collecting and copying theses and dissertations, the quantity and quality of postgraduate research and, by extension, the supervision (see Pillay & Balfour, 2011) conducted at each institution would become evident to peer scrutiny. The willingness of South African universities to risk public scrutiny and critique in the interest of furthering understandings of postgraduate education research is commendable, and it is notable that only one institution declined to participate in the Project.

In addition, academic members of the research team can arguably be described as the sort of intellectuals who have taken risks involving vulnerability when they encouraged student members of the team to "write an article about their subjectivity in the Project, their experiences of supervision, and their shifting identities from students to 'colleagues' (Molefe et al., 2011).

Busi Goba is one example from the Project of a female postgraduate researcher who is using the archive and database for her doctoral study of "A critical analysis of knowledge produced through postgraduate Mathematics Education research in South Africa (1995-2004)". In this study, which is still in progress, she explores how Mathematics Education knowledge is produced by focusing on the forms of knowledge that are researched in higher education, as well as the methodologies, theories and contextual factors considered when knowledge is produced, and why it is produced in that way. Drawing from PPER, Goba (2008:2) provides a "reflexive narrative of postgraduate Mathematics Education research studies using MEd and PhD theses as the unit of analysis". Her justification for this as her unit of analysis is that postgraduate theses reveal the methodological emphases of particular institutions, enabling her to provide a narrative of the research priorities and values of research into postgraduate Mathematics Education research studies in South Africa.

In her intellectual encounter, Goba (2008) explores the trends in methodologies used at different institutions as opposed to her providing a critique of one methodology. Thus the epistemological understanding of knowledge production provides insight, framing how postgraduate students produce knowledge in Mathematics Education research. By exploring patterns in research conducted at particular institutions she is developing insights into the power dynamics between postgraduate students and their supervisors when selecting topics, research questions, methodology and theory, in academic programmes. Finally, it also reveals changes in research productivity in historically black universities. These connections made by Goba (2008) with the dynamic research spaces of the physical archive and the electronic database are of consequence in that they seek to understand knowledge production by postgraduate researchers at a time when a society and its higher education institutions were undergoing great political change.

Another example from the Project is a study conducted by Lille Lekena (2012), a female International postgraduate researcher from an African state outside the borders of South Africa. She chose to embark on a masters study titled, "An Exploratory Analysis of Postgraduate Educational Research in Language and Race in South Africa: A Case study of Three Universities in the Western Cape in the Decade 1995-2004". Drawing from PPER electronic and physical database, Lekena (2012) provides an exploratory analysis of issues and trends in MEd and PhD theses on language and race. She specifically explores how particular knowledge is produced by focusing on the forms of knowledge, the methodologies and the contextual realities informing when knowledge is produced, and why it is produced in the way it is. From an understanding that language and race are not neutral descriptive categories, in South Africa, she surveys 421 sampled researches across three universities in the Western Cape region to see what studies have been done. Of those sampled, only 29 covered language and race issues and were all analysed using content analysis. It yields some understanding that there is a relationship between the history of the institutions and the kinds of research they produce about/on language and race, how it is researched. Finally, while the dominant theme amongst the sampled researches was Language, when language issues are being researched, race issues are inherently being researched either purposefully or coincidentally.

Conclusion

What is so critical about the physical archive and the electronic databases? Why are such research spaces important in terms of the transformational agenda for higher education and its responsiveness to change in South Africa? What is learned from this spatial conceptualisation about the products from a national survey of research? The value of the research space goes beyond the two spaces when the researcher (potential or actual) enters it to yield a third space. This third space is evident retrospectively when we consider the development of student researchers (such as Goba (2008) and Lekena (2012)) and their studies. The third space is a space that relies on mechanisms of connectivity. Goba's (2008) and Lekena's (2012) studies demonstrate the potential capacity and power generated when a researcher enters the creative third space that connects with and uses the two research spaces we have written about: the archive and the database spaces.

The coming into existence of the third space relies on the agency of a researcher. It holds the potential for any researcher working in creative and productive ways, engaging actively between and/or across the archive and database, to think and act in personally meaningful ways about postgraduate education research. The experienced, lived space of the researcher constitutes the possibility to connect the archive and database.

The researcher's connection with one or both of these spaces opens up possibilities for intellectual development or articulation of new understandings and ideas. We see this as a third intersecting space that has potential to generate enquiry and to anticipate multiple interpretations and representations of postgraduate research. It is within and through the PPER's third space that fresh questions about the theses and dissertations produced by postgraduate Education researchers in South Africa at the critical historical moment of the first decade of democracy are made possible.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Research Foundation (NRF) and The Ford Foundation for the opportunity and funding of the Postgraduate Project on Education Research.

Notes

1 Reference is made to theses rather than 'dissertations and theses', for the sake of simplicity.

2 UKZN Ethical clearance certificate HSS/0603/07.

3 EndNote® software.

References

Balfour RJ, Moletsane R & Karlsson J 2011. Speaking truth to power: Understanding education research and the educational turn in South Africa's new century. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):195-215. [ Links ]

Balfour R, Moletsane R, Karlsson J, Pillay G, Rule P, Nkambule T, Davey B, Lekena L, Molefe S, Madiya N, Bengesai A & Goba B 2008. Project Postgraduate Educational Research in Education: Issues, Trends, and Reflections (1995-2004): A Progress Report (2): July, 2008. Durban: Faculty of Education, UKZN. [ Links ]

Bengesai AV, Goba BB & Karlsson J 2011. Titles as discourse: Naming and framing research agendas as evident in theses titles in 1995-2004. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):252-268. [ Links ]

Bruch C 2003. How Public is the Public Domain? In Visions in Process -World Summit on the Information Society. Geneva 2003 - Tunis 2005. Berlin: Heinrich Böll Foundation. Available at http://www.worldsummit2003.de/download_de/Vision_in_process.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2013. [ Links ]

Bunting I 2002. The higher education landscape under apartheid. In N Cloete, R Fehnel, P Maassen, T Moja, H Perold & T Gibbon (eds). Transformation in Higher Education: Global Pressures and Local Realities in South Africa. Lansdowne: Chet/Juta. [ Links ]

Chisholm L (ed.) 2004. Introduction. In L Chisholm (ed). Changing Class: Education and social change in post-apartheid South Africa. Pretoria: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Cloete N, Fehnel R, Maassen P, Moja T, Perold H & Gibbon T (eds.) 2002. Transformation in higher education: Global pressures and local realities in South Africa. Lansdowne: Chet/Juta. [ Links ]

Council for Higher Education (CHE) 2004. Postgraduate research and supervision (ITL Resource No 7). Available at www.che.ac.za/documents/d000087/index.php. Accessed 10 July 2013. [ Links ]

Department of Education 1999. South African school library survey 1999: National report. Pretoria: Department of Education & Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Drossou O & Jensen H (eds) 2005. Visions in Process II: World Summit on the Information Society, Geneva 2003-Tunis 2005. Berlin: Heinrich Böll Foundation. Available at http://www.worldsummit2003.de/download_en/Visions-in-ProcessII%281%29.pdf. Accessed 7 March 2012. [ Links ]

Goba BB 2008. A critical analysis of knowledge produced through postgraduate mathematics education research in South Africa (1995-2004). Unpublished Research Proposal for PhD thesis. Durban: University of KwaZulu Natal. [ Links ]

Goba BB, Balfour RJ & Nkambule T 2011. The nature of experimental and quasi-experimental research in postgraduate education research in South Africa: 1995-2004. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):269-286. [ Links ]

Greve G 2003. Fighting Intellectual Poverty: Who Owns and Controls the Information Societies? In Visions in Process - World Summit on the Information Society. Geneva 2003 - Tunis 2005. Berlin: Heinrich Böll Foundation. Available at http://www.worldsummit2003.de/download_de/Vision_in_process.pdf. Accessed 7 March 2012. [ Links ]

Jansen J (ed.) 1991. Knowledge and power in South Africa: critical perspectives across the disciplines. Johannesburg: Skotaville. [ Links ]

Jansen J 2003. The state of higher education in South Africa: from massification to mergers. In J Daniel, A Habib & R Southall (eds). State of the Nation. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Jansen J, Herman C, Matentjie T, Morake R, Pillay V, Sehoole C & Weber E 2007. Tracing and Explaining Change in Higher Education: The South African Case. Review of Higher Education. Pretoria: Council on Higher Education. Available at http://www.che.ac.za/documents/d000146/10-Review_HE_SA_2007.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2008. [ Links ]

Karlsson J, Balfour R, Moletsane R & Pillay G 2009. Researching postgraduate educational research in South Africa. South African Journal of Higher Education, 23(6): 1086-1100. [ Links ]

Karlsson J & Pillay G 2011. Africanising scholarship: The case of UDW, Natal and UKZN postgraduate education research (1995-2004). South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):233-251. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/high/ high_v25_n2_a3.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2013. [ Links ]

Kuhlen R 2003. The Charter of Civil Rights for a Sustainable Knowledge Society - A Vision with Practical Consequences. In Visions in Process - World Summit on the Information Society. Geneva 2003 - Tunis 2005. Berlin: Heinrich Böll Foundation. Available at http://www.worldsummit2003.de/download_de/Vision_in_process.pdf. Accessed 7 March 2012. [ Links ]

Lefebvre H 1991. The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Lekena LL 2012. An exploratory analysis of Postgraduate Educational Research in Language and Race in South Africa: A case study of three universities in the Western Cape in the decade 1995-2004. Unpublished MEd dissertation. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at http://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10413/8844/ Lekena_Liile_Lerato_2012.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 10 July 2013. [ Links ]

Madiya N, Bengesai AV & Karlsson J 2011. What you do and where you are: A comparative analysis of postgraduate education research (1995-2004) from three South African higher education institutions. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):216-232. [ Links ]

Molefe S, Bengesai A, Davey B, Goba B, Lekena L, Madiya N & Nkambule T 2011. 'Now you call us colleagues': A reflection on the PPER students' experience of becoming researchers 2007 and 2009. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):373-387. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/high/ high_v25_n2_a11.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2013. [ Links ]

Moletsane R & Madiya N 2011. Postgraduate educational research on violence, gender, and HIV/AIDS in and around schools (1995-2004). South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):287-300. [ Links ]

National Education Policy Investigation 1993. Framework report and final report summaries. Cape Town: Oxford University Press/National Education Coordinating Committee. [ Links ]

Nkambule T, Balfour RJ, Pillay G & Moletsane R 2011. Rurality and rural education: Discourses underpinning rurality and rural education research in South African postgraduate education research 1994-2004. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):341-357. [ Links ]

Pillay G & Balfour RJ 2011. Post-graduate supervision practices in South African universities in the era of democracy and educational change 1994-2004. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):358-372. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/high/ high_v25_n2_a10.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2013. [ Links ]

Rule P 2011. On the right and left of the centre: ABET and ECE postgraduate educational research in South Africa, 1995-2004. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):322-340. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/high/ high_v25_n2_a8.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2013. [ Links ]

Rule P, Davey B & Balfour RJ 2011. Unpacking the predominance of case study methodology in South African postgraduate educational research, 1995-2004. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(2):301-321. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/high/ high_v25_n2_a7.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2013. [ Links ]

Said E 1994. Representations of the intellectual: The 1993 Reith Lectures. New York: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

Van Buuren A & Edelenbos J 2004. Why is joint knowledge production such a problem? Science and Public Policy, 31:289-299. [ Links ]

World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) 2003. In Visions in Process: World Summit on the Information Society, Geneva 2003-Tunis 2005. Berlin: Heinrich Böll Foundation. Available at http://www.worldsummit2003.de/download_de/Vision_in_process.pdf. Accessed 7 March 2012. [ Links ]