Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.33 n.3 Pretoria Jan. 2013

Ecological aspects influencing the implementation of inclusive education in mainstream primary schools in the Eastern Cape, South Africa

J L GeldenhuysI; N E J WeversII

ISchool of Education Research and Engagement, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. johanna.geldenhuys@nmmu.ac.za

IISchool of Education Research and Engagement, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

ABSTRACT

Despite efforts worldwide to ensure quality education for all learners through inclusive education, indications are that many learners, especially those that experience barriers to learning, are still excluded from full access to quality and equitable education opportunities in mainstream primary schools. This article uses a qualitative approach and phenomenological strategy to focus on the ecological aspects influencing the implementation of inclusive education in mainstream primary schools in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Observation and semi-structured interviews were conducted with 28 participants from seven schools to gather data, whilst a process of framework analysis was used for the analysis of the data. The investigation revealed that the implementation of inclusive education is not only hampered by aspects within the school environment, but also by aspects across the entire ecological system of education.

Keywords: Assessment and Support Strategy, barriers to learning, ecological model, identification, inclusive education, mainstream primary schools, screening

Introduction

Most of the earlier work on inclusive education (IE) has concentrated on the rationalization for inclusion and focused on the rights of people with disabilities to a free and suitable education (Nieuwenhuis, 2007). The rights and ethics discourse is one of the ways to justify IE. It states that the existence of a dual education system prevents systematic changes to make education responsive to an increasingly diverse society. This justification is often based on the ideals of social justice (Artiles, Harris-Murri & Rostenberg, 2006). The ideals of social justice can be seen as complete and equal participation of all groups in a society that is mutually designed to meet their needs and in which individuals are both self-determining, i.e. able to develop their full capacities, and interdependent, i.e. capable to interact democratically with others, as well as a society in which the distribution of resources is equitable and all members are physically and psychologically safe and secure (Adams, Bell & Griffin, 2007). Engelbrecht (1999) explains that the rights discourse is committed to extending full citizenship to all people and emphasises equal opportunity, self-reliance and independence. For Engelbrecht (2006) IE within the South African context is therefore framed within a human rights approach and based on the ideal of freedom and equality as depicted by the Constitution.

The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action endorses the rights discourse, with a strong focus on the development of inclusive schools and states that "schools should accommodate all children, regardless of their physical, intellectual, social, linguistic, or other conditions" (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], 1994:6). The underlying principle of IE is to provide an education that is as standard as possible for all learners, adapting it to the needs of each learner (Thomazet, 2009).

By applying the principle of social justice, which is focused on providing equitable outcomes to marginalised individuals and groups due to barriers embedded in social, economic and political systems (Dreyer, 2011), IE can improve the lives of all people.

IE depends on the capacity of the school, and therefore on the capacity of educators, to be innovative and to put differentiation into place (Thomazet, 2009). Learners with learning impairments and special needs should not be segregated from other learners, but should be supported in the mainstream in such a way that their needs are met (Hugo, 2006). While IE has been implemented successfully in a number of countries, some countries, including South Africa, are still seeking to achieve this goal (Nguyet & Ha, 2010). It is against this background that the article aims to determine which ecological aspects have an influence on the implementation of IE in mainstream primary schools.

The shift towards inclusive education in South Africa

During the apartheid era in South Africa, learners were not only educated separately according to race, but a separate special education system existed for learners with disabilities or impairments. This segregated and fragmented education system needs to be addressed to bring education practice in South Africa in line with international trends which focus on the inclusion of learners with special education needs in mainstream classes (Engelbrecht, 2006). South Africa's educational past makes it consequently ideal for social justice teaching with its focus on improving the life chances of all children, teaching for diversity, multicultural education, anti-oppressive education, and addressing generic issues influenced by privilege and power (Philpott & Dagenais, 2012).

To achieve the ideal of IE and social justice in South Africa, the Department of Education (DoE) embarked on policy reviews and policy changes to ensure equal, nondiscriminatory access to education for all. These changes resulted in the promulgation of the South African Schools Act (SASA) of 1996 (South Africa, 1996a). One of the key features of the SASA is the affirmation of the right of equal access to basic and quality education for all learners, without any discrimination whatsoever. The principle of quality education for all learners is highlighted by the stipulation that a public school must promote the best interests of the school through the provision of quality education for all learners in the school (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001).

One of the most influential IE policies developed by the DoE in recent years is the Education White Paper 6 (EWP6). The EWP6 provides the framework for the implementation of IE in all public schools. It aims to address the diverse needs of all learners in one undivided education system. Based on the rights discourse, the EWP6 strives to steer away from the categorisation and separation of learners according to disability but to facilitate their maximum participation in the education system (DoE, 2005). The EWP6 provides guiding principles for the new education system it envisages for South Africa, and includes the following: protecting the rights of all people, and making sure that all learners are treated fairly; ensuring that all learners can participate fully and equally in education and society; providing equal access for all learners to a single, IE system; and making sure that all learners can understand and participate meaningfully in the teaching and learning process in schools (DoE, 2002:8).

Despite the measures by the DoE to ensure equal, accessible and quality learning opportunities for all learners, many learners may not receive the attention they deserve in mainstream classrooms (Ladbrook, 2009). According to Rossi and Stuart (2007), these learners are often retained, placed in special education, drop out of high school, or lose confidence; all of which could have been prevented.

Research conducted into educator preparedness for IE in South Africa (Hay, 2003; Magare, Kitching & Roos, 2010; Pieterse, 2010; Pillay & Di Terlizzi, 2009) and educators' perspectives concerning IE (Mayaba, 2008; Magare et al., 2010:53) indicate that the shift towards IE has placed a strain on educators, because "prior to 1994, educators in South Africa were trained only for either mainstream education or specialised" in a field. Likewise, mainstream education has not been designed for diversity or for responding to the needs and strengths of its individual learners, and therefore the task of ensuring that social justice and equity goals are met for every learner is a challenge for mainstream schools (Vlachou, 2004). The goal of implementing IE in schools in South Africa is therefore still far from being achieved.

Inclusive education and Bronfenbrenner's ecological framework

In order to understand aspects that influence the implementation of IE in mainstream primary schools Bronfenbrenner's eco-systemic framework was adopted. This framework focus on the explanation of systemic influences on child development. The development of learners however is influenced by various features, which Bronfenbrenner divides into five subsystems:

The microsystem which represents an individual's immediate context, is characterised by direct, interactional processes as familial relationships and close friendships (Bronfenbrenner, 1994; Duerden & Witt, 2010).

The mesosystem comprises the interrelations between two or more settings in which the developing person actively participates. In terms of learners, this refers to relations between settings such as the home, school, neighbourhood and peer group (Bronfenbrenner, 1979:25). The mesosystem can therefore be described as a set of microsystems that continually interact with one another (Donald, Lazarus & Lolwana, 2010).

The exosystem refers to one or more settings that do not involve the learner as an active participant, but in which events occur that affect, or are affected by, what happens in the setting containing the learner (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), for example, school policies created by school governing bodies (SGBs) to provide for the needs of learners that experience barriers to learning.

The macrosystem consists of the larger cultural world surrounding learners together with any underlying belief systems and includes aspects such as government policies, political ideology, cultural customs and beliefs, historical events and the economic system (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Duerden & Witt, 2010).

The chronosystem represents the changes that occur over a period of time in any one of the systems (Donald et al., 2010).

Bronfenbrenner's framework, according to Singal (2006) and Bronfenbrenner (1979), thus allows an exploration of IE as being about the development of systems and the development of individuals within these systems. By identifying the inter-connectedness within and between these systems, it facilitates a better understanding of IE. This allows for the exploration of the development of IE as constructed and restricted by aspects operating in different systems and an examination of how practices are shaped by the interactive influence of individuals and their social environment. Engelbrecht (1999:5) confirms that "an understanding of the context is the first step towards understanding new developments in education and the movement towards inclusive education".

Social justice principles, e.g. more equal distribution of resources and providing equal opportunities to marginalized individuals and groups (Dreyer, 2011), directly engage with the very contexts and systems in which IE is embedded and seek to improve the influences of these systems on the learning experiences and relationships among learners.

Empirical investigation

The aim of the research was to investigate which ecological aspects influence the implementation of IE in mainstream primary schools in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Since the study entailed an inquiry into the phenomenon of IE a qualitative research approach was considered to be the most appropriate, because "it is able to grasp the meanings of actions, the uniqueness of events, and the individuality of persons" (Walker & Evers, 1999:43).

A phenomenological strategy was thus deemed to be the most suitable one to achieve the research aim of this study. One of the strengths of this strategy according to Garza (2007) is the flexibility of the phenomenological approach and its methods as it can be applied to ever widening areas of inquiry.

Data gathering in this investigation was done by means of semi-structured inter- views to ensure that similar data were collected from all the interviewees (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010). Face validity applied to the interview schedule as the open-ended questions relate to experiences participants could encounter by their involvement with IE (Struwig & Stead, 2001). Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2007:321) validate this choice by stating that open-ended questions "...enable the participants...to explain and to qualify their response..." This method was supplemented by the observation of the class and school environment to examine how barriers to learning were managed in the participating schools. A checklist was used to verify this information and, where necessary, additional notes were made for integration with data obtained from the interviews. Observations, according to Hartas (2010), also helped to increase the credibility and reliability (trustworthiness) of the study since it was possible to see how educators deal with learners experiencing barriers to learning.

Purposeful sampling was employed as it was able to elicit the most information rich sources in the field of research (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010:147).

Interviews were conducted with a total of 28 participants, including two district officials, six school principals, and 20 individual educators from selected mainstream primary schools. Seven schools in the Graaff Reinet district were included in the study and the criteria for selecting the schools were learner enrolment, learners who experience barriers to learning, medium of instruction, socio-economic circumstances, previously disadvantaged schools, former Model C schools, and financial status of the school.

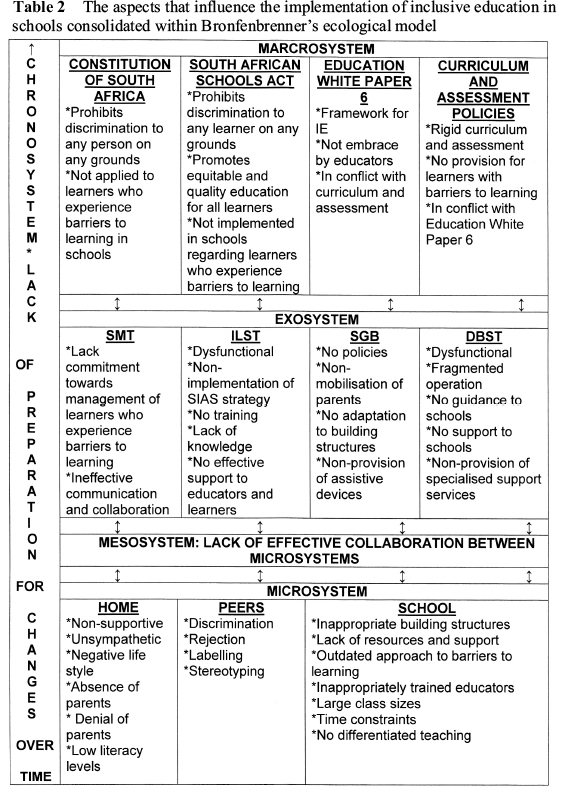

The data collected were analysed using the five-step framework data analysis process by Lacey and Luff (2009). The first step involves familiarisation with the transcripts of the collected data, followed by the identification of the thematic framework, which entails the recognition of emerging themes. The third step involves the use of numerical or textual codes to identify specific pieces of data which correspond to different themes. The fourth step known as charting involves the creation of charts of data based on the headings from the thematic framework, so that the data can easily be read across the whole data set. The final step involves the analysis of the most salient characteristics of the data through mapping and interpretation. This enables the generation of a schematic diagram of the phenomenon under investigation, thus guiding the interpretation of the data set (Srivastava & Thomson, 2009) as indicated in Table 2.

Ethical clearance for the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the university under whose auspices the research was conducted, and written permission was obtained from the Eastern Cape DoE to conduct the research in selected schools. Participants were assured that the information would be treated confidentially and that their anonymity would be guaranteed, and all the participants provided -written informed consent to participate in the study.

Trustworthiness refers to the extent to which the data obtained in the study is plausible, credible, and trustworthy (McMillan & Schumacher, 2010). The strategies outlined in Table 1 were employed to ensure the trustworthiness of the research.

Discussion of findings

The findings are now be discussed on the basis of the layout in Table 2, which provides a summary of the ecological aspects that influence the implementation of IE in mainstream primary schools included within Bronfenbrenner's ecological model. These findings relate to the perceptions of the participating educators and officials only, although statements are made about other role players' (e.g. parents and learners) behaviours and views. Verbatim quotations from the interviews of participating educators are provided within quotation marks as evidence of the findings. Furthermore, this qualitative study was conducted in seven schools in the Eastern Cape Province to obtain information-rich data regarding the research problem and all claims made are thus located within these limitations.

Aspects at the microsystemic level

Findings at this level include three microsystems in which the learner that experience barriers to learning is involved, namely, the home environment, peer group and school.

Many learners come from unsupportive home environments. Parents are generally not actively involved in the development of learners that experience barriers to learning. Many parents seldom provide effective stimulation to their children at home and perceive it as the sole task of the school. As one educator participant indicated, "You have parents who care nothing about the child's education".

Owing to parents' low education levels, they struggle to find permanent employment, and therefore experience varying levels of poverty. Learners that grow up in such home environments will be more inclined to be at risk of poor academic performance. Furthermore, many learners are raised by grandparents, who in most instances are not able to provide the necessary support at home, due to their low literacy level.

Parents sometimes display unsympathetic behaviour towards their children, with negative references to the barriers to learning that their children are experiencing. Instead of loving and supporting their children, they sometimes make negative comments such as "Yes, you are stupid" to their children, which may lead to the development of a low self-esteem in the child and in turn may adopt negative responses to any form of support from the school.

The lifestyle of parents also influences their children's development. The outcomes of the investigation suggest that many learners are neglected at home because of parents' drug and alcohol abuse. One participating educator remarked: "[M]any of the parents drink, and they use drugs and things". Learners from such households are in many cases forced to take care of the household and look after themselves. This burden of extra responsibility at home impacts negatively on these learners' ability to respond positively to teaching and learning opportunities at school, which, in turn, impedes the management of these learners in the mainstream schools.

Some parents are in denial that their children experience barriers to learning. As one participant commented, "[M]any of the parents don't want to acknowledge that their children are experiencing barriers to learning". Parents may perceive their children's barriers to learning as a reflection on the quality of their parenting. They may therefore resist any recommendations from the school to assess their children to determine the nature and extent of their barriers to learning with a view to implementing effective support programmes to assist learners with special education needs. As one educator participant stated, "[M]any of the parents don't even want to give permission for their children to be assessed".

According to Digman and Soan (2008) children who are negatively influenced by their home environments struggle to meet academic demands and to manage their relationships with others, while Pillay (2004) points out that physical constraints, such as overcrowded homes, the lack of water, electricity and finances, may cause learners to underperform at school.

The findings with regard to the microsystem of the peer group revealed that learners experiencing barriers to learning are often discriminated against, rejected, labelled, and stereotyped by their peers as a result of them being different and their perceived lesser abilities. One educator participant asserted that "[T]hey are rejected by some of the learners. When they have to play games where intelligence is required, they say 'No, we don't play with him, he is stupid'". As one participant observed, "Immediately that child shrinks away completely. And that child believes he is stupid".

Having positive relationships with peers is crucial for learners' social development. The investigation revealed that there was no deliberate attempt on the part of many schools to encourage positive relationships between peer groups and to create interaction and support opportunities for learners of diverse abilities in and outside the classroom. The lack of intervention from the school and the parents to encourage and stimulate strong peer relationships may cause those learners that experience barriers to learning to become socially isolated from their more able peers, and to miss out on development opportunities.

Although one of the perceived benefits of IE is the positive effects of the social interaction between learners that experience barriers to learning with their able peers (Lewis & Doorlag, 2003) the findings of this research disclosed the contrary.

The findings of the investigation indicated that mainstream schools are currently not very accommodating and user-friendly microsystems for learners that experience barriers to learning. The investigation revealed a lack of structural modification among the participating schools to accommodate the needs of learners with limited mobility. One participating school principal reflected that "[it is] a grey area that we need to address...she must have her own toilet". At some of the participating schools, learners repeatedly have to climb steep flights of stairs without any assistance to access the first-floor classrooms where some of their learning areas are taught. This places a physical and emotional strain on these learners, and it may influence their ability to concentrate and participate in learning and development activities. It also poses a safety risk, given the number of learners that use the stairs at the same time, and the lack of supervision on the stairs when learners change classes.

Many learners that experience barriers to learning continue to be excluded from aspects of school life, because the required resources and support are lacking. This results in learners not being able to participate fully in classroom activities, and they are thereby denied the opportunity to develop optimally. One educator participant commented "But we do not have all the equipment to test the children's ears or to test their eyes".

Most of the participating educators still adopt and prefer the medical approach to barriers to learning which overemphasized learners' 'differentness' and limitations at the expense of their inherent strengths. The adoption of the medical approach to barriers to learning has a direct bearing on the implementation of IE, because of the educators' unrealistic expectations that these learners must perform at the same cognitive or physical level as their more able peers, which results in prolonged absenteeism or dropping out. Participating educators commented as follows: "I want the child to count to 10 today, then he stays away from school" and "[T]hey are the learners who drop-out... . They take themselves out of school as a result of the barriers they experience".

Many of the participating educators perceived their training for IE as unsuitable. Typical remarks by educator participants were: "I will not be able to give justice to an inclusive class, because...the training is lacking" and "[M]ost of us are just trained to teach in a normal class situation". Pieterse (2010) is in agreement that the implementation of IE is hampered by inappropriately trained educators who are frustrated and unmotivated and experience feelings of guilt and inadequacy.

Most educators in the participating schools reported that they have to manage classes with a class size in excess of 40 learners per class, which in some instances includes a significant number of learners that experience barriers to learning. As one participant educator observed, "We have extremely big classes...of up to 45 in a class, where learners that experience barriers to learning are included". In other schools, where the learner enrolment is relatively low, educators are not only challenged by the diverse learner population, but they also have to teach multi-graded classes which makes the implementation of IE even more challenging. One participating educator asserted that "it is difficult for us to do these groupings because of these multi-grade classrooms. You have two grades in one classroom". Consequently, many learners are in most cases just "dragged along" with their more able peers, without ever mastering the basic skills. One educator remarked as follows on the effect of large class size on IE: "[T]hey can't swim with the mainstream. They will end up drifting further and further away". Learners that experience barriers to learning therefore end up "disappearing into the masses", without being given the opportunity to participate meaningfully and to develop in the mainstream classes.

Participating educators found it difficult to accommodate learners that experience barriers to learning to work at a pace that suits their special abilities. A participating school principal referred to educators' desire to complete work within a certain time frame, as required by the DoE as follows: "[M]any of the teachers want to be at a certain point at a certain time, according to the so-called pace setters". Another participating educator is of the opinion that: "[A]s teacher, you must give thorough attention to the children, which you can't do". Likewise, Pieterse (2010) concurs that because of the challenge of large numbers of learners needing support and the associated limitation in time constraints, the majority of learners who experience barriers to learning simply go unsupported in schools and consequently nullify the envisaged benefits of their inclusion in diverse mainstream classrooms.

The findings revealed that the participating educators seldom employed a variety of teaching techniques to accommodate diverse learning styles of learners and to provide equal development opportunities for all learners or used alternative modes of assessment. As one participating educator reasoned, "Now why must you teach the child something that you know he will not be able to do in 20 years' time?" The following comment is typical of the sentiments that were expressed by participating educators regarding differentiated assessment: "[I]t doesn't matter whether it is a child with a learning barrier or a brilliant child, they are treated the same. Our hands are chopped off".

However, Armstrong, Armstrong and Spandagou (2010) emphasise that educators in the mainstream are required to modify their teaching strategies and to tackle the diverse needs of learners, whereas Rose and Howley (2007) underline the need for dedicated teachers to empower and equip themselves professionally, so that they could deliver quality education.

Aspects at the mesosystemic level

The findings at the mesosystemic level revealed the nature of the different collaborations and cooperation between the three microsystems discussed in the previous section.

Participants in this study indicated that many parents do not involve themselves much in the education and development of their children, and it is left completely to the school. The lack of support from parents places much strain on educators, which, in turn, hampers the implementation of IE in the school. At many schools parental involvement is limited to the attendance of general parent meetings where parents are informed about problem behaviour that their child might be displaying, parental involvement in fundraising events, and meetings to discuss the child's progress when retention forms need to be completed. There also seems to be a lack of constructive effort on the part of schools to create and maintain effective positive partnerships through continually involving the parents in all aspects of their child's development. The reluctance of some parents to cooperate with the school may therefore be ascribed to the fact that these parents are not treated as equal partners in the development of their children. Due to the lack of collaborative partnerships between educators and parents, learners are not able to comprehend how the school and their parents relate to each other in terms of the learners' development, and they consequently may see their educators and their parents as being separate entities, working independently of each other.

The SASA (South Africa, 1996a) acknowledges that parents are equal partners in education, while Wilcox and Angelis (2009:37) emphasised the significance of a common goal and collaboration amongst role-players, in order to improve learner achievement. Nevertheless, the investigation revealed that there was a general lack of constructive collaboration and cooperation between the school and the parents.

Aspects at the exosystemic level

The findings concerning aspects at the exosystemic level focused on the school management team (SMT), institutional level support team (ILST), SGB and district-based support team (DBST) and their current management of learners who experience barriers to learning at the participating schools.

The empirical investigation revealed that SMTs in participating schools do not display sufficient commitment to the management of learners that experience barriers to learning in mainstream primary schools. In this study, participating principals as leaders of the SMTs in their schools, expressed a negative attitude towards the inclusion of learners that experience barriers to learning in mainstream primary schools. Instead of being visible and vocal campaigners for inclusive practices, participating principals and participating members of SMTs rather articulated that there was an urgent need for these learners to be removed from mainstream classes and to be educated separately in special classes or special schools. In some instances it was discovered that even when SMT members were leading the ILSTs, no constructive efforts were made to provide meaningful learning and developmental opportunities and support to learners that experienced barriers to learning. This has a ripple effect on the way educators manage IE. In many cases learners are simply condoned from one grade to next without being given any kind of support to improve their skills and subse- quently under achieve. This is contrary to the expectations of the DOE (2009:13) that principals and their SMTs "should have an unwavering belief in the value of inclusive schooling and considerable knowledge and skills for translating the concept into practice".

The investigation reveals that ILSTs are not operational in most of the participating schools, and that their current activities are mostly limited to the identification of learners that experience barriers to learning, without reaching the stage where learners are exposed to support programmes to make their participation in school programmes meaningful. One participating educator remarked that "We just talked about it, but we did nothing about it".

The Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support (SIAS) Strategy forms the basis on which IE is built and provides guidelines regarding early identification of learners' strengths and weaknesses, correct assessment strategies of the nature and extent of the barriers that learners may be experiencing, and effective design and implementation of individualised support plans for these learners (DoE, 2008:88). The investigation revealed that educators do not fully understand their roles and responsibilities regarding the SIAS Strategy due to the lack of effective and structured in-service training programmes, and showed negative outcomes on the implementation of IE due to non-compliance with SIAS Strategy.

The findings of the empirical research further revealed that SGBs are not really involved in and concerned with the development of policies that support the implementation of IE. However, according to SASA (South Africa, 1996a), SGBs do have an important governance role to fulfil regarding the development of school policies that safeguard the interests of all learners in the school, and to ensure that no learner is discriminated against on any grounds.

The last findings at the exosystemic level revealed that at this stage DBSTs at the participating schools are neither capacitated nor structured to provide effective guidance and support to schools with respect to the implementation of IE. This was confirmed by a participating district official, who stated that "[U]nfortunately our DBST is not really operational...it's not really got off the ground". According to the DOE (2007), DBSTs must consist of specialised support personnel to provide a gateway for schools to access specialised support services for learners that experience barriers to learning and are tasked with providing appropriate practice-oriented training opportunities for educators, to enable them to implement IE.

Aspects at the macrosystemic level

The macrosystem refers to policies and structures which provide the blueprint on which education provisioning in South Africa is based. The implications of policies and the actions of structures have an influence on the management of IE in schools.

The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (South Africa, 1996b) provides the outline for the democratic operation of all institutions. In terms of education, the Constitution demands and guarantees non-discriminatory and equal access to quality education for all learners. The Constitution contains the fundamental principles which influence the operations of all other institutions within an ecological system. The current management of IE in many schools constitutes a serious violation of the stipulations of the Constitution.

Based on the provisions of the Constitution of South Africa, the SASA (South Africa, 1996a) provides the framework for the management of public schools with regard to the rights, roles, and responsibilities of the different role players. The SASA prohibits any form of discrimination directed at any learner in terms of access to quality and equal education. However, most learners that experience barriers to learning are still discriminated against in terms of the kind of developmental and participatory opportunities that they are provided with in mainstream primary schools.

The EWP6 (DoE, 2001) formally introduces the concept of IE and provides the framework for the implementation of an IE system in South Africa. It clearly indicates the requirements for IE, with specific reference to the roles and responsibilities of role players at the different levels of education. The EWP6 also emphasises the need to adapt school programmes to accommodate the diverse needs of all learners. However, most of the participating educators struggle to comprehend the relevance of the EWP6 in the context of the current Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statements (CAPS) that they are expected to implement in schools. This is evident from the following comment made by one of the participants: "[W]hen I read the White Paper [the EWP6], I tell myself it was just printed because it must be there. But, in reality, it is not applicable to us".

The Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statements provide guidelines to schools in terms of curriculum content and assessment requirements. However, the CAPS are structured in such a way that they do not support the requirements of the EWP6, which promotes curriculum and assessment differentiation. The current CAPS thus undermine the implementation of IE. The reason for this perceived contradiction between the EWP6 and the CAPS can be attributed to the fact that these policies were generated by two separate directorates, and were seemingly not properly aligned.

As long as the perceived discrepancies between EWP6 and the CAPS continue to exist, educators will remain confused on how to manage inclusive classes in mainstream schools, and, as a result, the implementation of IE will remain a challenge. A participating district official commented as follows on the perceived discrepancies between the CAPS and the EWP6: "[Y]ou have that discrepancy between the policy, as outlined in the White Paper [the EWP6] and the reality in the classroom".

Aspects at the chronosystemic level

The empirical investigation revealed that, while the transition has been made to an IE system in South Africa, the following key requirements have not been properly addressed to prepare schools and educators for the changes needed in the education system over time and to align the education system to cope with the transition to and implementation of IE: no structural modifications have been effected to make mainstream primary schools more accessible for all learners; there is a lack of availability of assistive devices to support learners in mainstream primary schools; there is insufficient training and capacitating of mainstream educators for IE; there is a lack of purposeful public advocating of education policies regarding IE; learners are not being prepared for the changing education contexts in which they find themselves; the CAPS have not been aligned with the requirements of IE, as outlined in the EWP6; no effective support structures are available in schools to manage learners that experience barriers to learning; and the systems in schools to monitor and improve the implementation of IE are not effective. A participating principal commented as follows on the preparedness of schools to implement IE: "I think there is justification for inclusive education but the basis...on which [inclusive] teaching must take place, must first be rectified".

This need for preparation of schools for change over time seems to be a general problem in South African society and is described by Mashau, Steyn, Van der Walt and Wolhuter (2008:418) as "the lack of connection between...official policy and implementation or delivery".

Conclusion

This article presented the ecological aspects that influenced the implementation of IE in mainstream primary schools consolidated within Bronfenbrenner's ecological framework and the findings were summarised in Table 2. These aspects are also indicative of the poor management of learners who experience barriers to learning and are embedded in all five systems of Bronfenbrenner's framework.

Based on the discussion of the findings of the empirical investigation, it can be concluded that IE has not been implemented effectively in most mainstream primary schools in the Eastern Cape. The implementation of IE has been seriously hampered by a lack of structured cohesiveness in terms of the preparedness of role players at different levels of the education system, the non-functioning or unavailability of support structures as a result of inappropriate training, and the reluctance of role players to embrace IE within the different layers of the ecological system. On the lower levels, these hampering aspects include the lack of early identification of learners who experience barriers to learning, no proper assessment of learners' strengths and weaknesses, no individualised support plans, little individualised attention, the neglect of learners who experience barriers to learning, and limited collaboration and cooperation between microsystems.

To ensure the implementation of IE in schools in South Africa, and the accompanying social justice, urgent interventions are needed at all levels of the education system.

Interventions on the chronosystemic level include the regular revision and adjustment of national education policies to schools at exosystemic level to maximize the utilization of resources, the regular improvement of relationships between role players at mesosystemic level, and the preparation of learners for the changing circumstances in which they receive their education in schools.

With regard to the macrosystem, the current implementation of national policies requires intervention from the National and Provincial Departments of Education to ensure that all learners, irrespective of their abilities receive quality and equitable education. For example, all current education policies should be integrated and aligned with EWP6 to eradicate any confusion and the perception that inclusive education is an alternative form of education. Furthermore, flexible curricula should be developed to ensure that learners' diverse abilities are catered for, and should not be prescriptive, but rather provide a broad framework for educators within which they are allowed to adapt the main curriculum to the specific needs of learners. Assessment policies should be developed to allow learners to be assessed according to their needs and abilities. Currently all learners are subjected to uniform assessment standards and modes of assessment to the detriment of learners who experience barriers to learning.

On the exosystemic level SGBs should become more acquainted with the requirements of inclusive education. They should receive proper training so that they are able to develop school policies that ensures the right of all learners to receive quality and equitable educational and developmental opportunities. Moreover, given the important function of DBSTs in ensuring that schools are prepared and guided towards the effective implementation of inclusive education, the structuring, staffing and capacitating thereof should be a high priority.

Interventions strategies on the mesosystemic level need to focus on the creation and maintenance of good relationships and purposeful partnerships among the school, parents and learners.

The microsystem is a very important layer of the educational ecosystem because learners are directly involved in this layer. Parents, for example, should be subjected to parent skilling programmes to improve the quality of their parenthood in cases where they are displaying unsympathetic behavior and negative attitudes towards their children who experience barriers to learning. Schools, on the other hand, should make concerted efforts to acquire the necessary resources to ensure that learners experiencing barriers to learning have the same quality access to teaching and learning opportunities as their more able peers. This could be done by obtaining sponsorships and the involvement of local businesses and health services. Schools should involve parents as equal partners in the education and development of learners. This can be done, for example, by the creation of cluster parent-educator groups where certain educators are assigned to a certain group of parents to provide assistance regarding support to learners. All practising educators should receive in-service training regarding the management of inclusive classrooms through well-structured training and staff development programmes. Lastly, learners must also be educated to become active participants in their development with a view to becoming self-efficient and contributing members of their communities. Only if individual learners accept themselves on the basis of their specific barriers, will they be able to relate and respond positively to support programmes available to them.

References

Adams M, Bell LA & Griffin P (eds) 2007. Teaching for diversity and social justice. New York: Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Armstrong AC, Armstrong D & Spandagou I 2010. Inclusive education: International policy and practice. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Artiles AJ, Harris-Murri N & Rostenberg D 2006. Inclusion as social justice: Critical notes on discourses, assumptions, and the road ahead. Theory into Practice, 45:260-268. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4503_8 [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner U 1979. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner U 1994. Ecological models of human development. International Encyclopaedia of Education, 3:37-43. [ Links ]

Cohen L, Manion L & Morrison K 2007. Research Methods in Education (6th ed). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE) 2001. Education White Paper 6: Special needs education. Pretoria: DoE. Available at http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspxfileticket=gVFccZLi%2FtI%3D&tabid=191&mid=484. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE) 2002. Drug Abuse Policy Framework. Government Gazette, 24172. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE) 2005. Framework and management plan for the first phase of implementation of inclusive education. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE) 2007. Guidelines to ensure quality education and support in special schools and school resource centres. Pretoria: DoE. Available at http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=6Jp4pUbzHhg%3D&t. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE) 2008. National Strategy on Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support. Pretoria: DoE. Available at http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket= Jzz5HGcjdIg%3D&tabid=436&mid=1753. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE) 2009. Strategy for the integration of services for children with disabilities. Pretoria: Department of Social Development. Available at http://www.ruralrehab.co.za/uploads/3/0/9/0/3090989/ strategy_integr_services_cwd_dsd_2009.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Digman C & Soan S 2008. Working with parents: A guide for education professionals. London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Donald D, Lazarus S & Lolwana P 2010. Educational Psychology in social context: Ecosystemic applications in Southern Africa (4th ed). Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Dreyer LM 2011. Hope anchored in practice. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25:56-69. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/ high/high_v25_n1_a5.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Duerden MD & Witt PA 2010. An ecological systems theory perspective on youth programming. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 28:108-120. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht P 1999. A theoretical framework for inclusive education. In P Engelbrecht, L Green, S Naicker & L Engelbrecht (eds). Inclusive education in action in South Africa. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht P 2006. The implementation of inclusive education in South Africa after ten years of democracy. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21:253-264. Available at http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2FBF03173414.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Garza G 2007. Varieties of phenomenological research at the University of Dallas: An emerging typology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 4:313-342. doi: 10.1080/14780880701551170 [ Links ]

Hartas D 2010. Quantitative research as a method of inquiry in education. In D Hartas (ed). Educational research and inquiry: Qualitative and Quantitative approaches. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. [ Links ]

Hay J 2003. Implementation of the inclusive education paradigm shift in South African education support services. South African Journal of Education, 23:135-138. [ Links ]

Hugo A 2006. Overcoming barriers to learning through mediation. In MM Nieman & RB Monyai (eds). The Educator as mediator of learning. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Lacey A & Luff D 2009. Qualitative data analysis. Yorkshire: The National Institute for Health Research. [ Links ]

Ladbrook MW 2009. Challenges experienced by educators in the implementation of inclusive education in primary schools in South Africa. MEd dissertation. Pretoria: University of South Africa. Available at http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/ 3038/dissertation_landbrook_m.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Leedy PD & Ormrod JE 2010. Practical research: Planning and design. New Jersey: Pearson Education. Available at ftp://doc.nit.ac.ir/cee/jazayeri/Research%20Method/Book/ Practical%20Research.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Lewis RB & Doorlag DH 2003. Teaching special students in general education classrooms (6th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Lomofsky L & Lazarus S 2001. South Africa: First steps in the development of an inclusive education system. Cambridge Journal of Education, 31:303-317. doi: 10.1080/03057640120086585 [ Links ]

Magare I, Kitching A & Roos V 2010. Educators' experiences of inclusive education in learning contexts: an exploration of competencies. Perspectives in Education, 28:52-63. [ Links ]

Mashau S, Steyn E, Van der Walt J & Wolhuter C 2008. Support services perceived necessary for learner relationships by Limpopo educators. South African Journal of Education, 28:415-430. Available at http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/saje/v28n3/a09v28n3.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Mayaba PL 2008. The educators' perceptions and experiences of inclusive education in selected Pietermaritzburg schools. MSc dissertation. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at http://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/xmlui/bitstream/handle/ 10413/958/Mayaba_PL_2008.pdf?sequence=3. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

McMillan JH & Schumacher S 2010. Research in Education - Evidence-Based Inquiry (7th ed). Boston: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Nguyet DT & Ha LT 2010. Preparing teachers for inclusive education. Vietnam: Catholic Relief Services. [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuis J (ed.) 2007. Growing human rights and values in Education. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Philpott R & Dagenais D 2012. Grappling with social justice: Exploring new teachers' practice and experiences. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 7:85-99. doi: 10.1177/1746197911432590 [ Links ]

Pieterse G 2010. Establishing a framework for an integrated, holistic, community based education support structure. DEd thesis. Port Elizabeth: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. Available at http://dspace.nmmu.ac.za:8080/jspui/bitstream/10948/1158/1/ Glynis%20Pieterse.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Pillay J 2004. Experiences of learners from informal settlements. South African Journal of Education, 24:5-9. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/ educat/educat_v24_n1_a2.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Pillay J & Di Terlizzi M 2009. A case study of a learner's transition from mainstream schooling to a school for learners with special educational needs (LSEN): lessons for mainstream education. South African Journal of Education, 29:491-509. Available at https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10210/7764/Jace%20 Pillay%20and%20Marisa%20Di%20Terlizzi_2009.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Rose R & Howley M 2007. The practical guide to special educational needs in inclusive primary classrooms. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. [ Links ]

Rossi J & Stuart A 2007. The evaluation of an intervention programme for reception learners who experience barriers to learning and development. South African Journal of Education, 27:139-154. Available at https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10210/7765/June%20 Rossi%20and%20Anita%20Stuart_2007.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Singal N 2006. An ecosystemic approach for understanding inclusive education: An Indian case study. European Journal of Psychology of Education, XXI:239-252. Available at http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2FBF03173413.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

South Africa 1996a. South African Schools Act. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 1996b. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Srivastava A & Thomson SB 2009. Framework analysis: A qualitative methodology for applied policy research. Journal of Administration and Governance, 4:72-79. Available at http://www.joaag.com/uploads/06_Research_Note_Srivastava _and_Thomson_4_2_.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2013. [ Links ]

Struwig FW & Stead GB 2001. Planning, designing and reporting research. Cape Town: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Thomazet S 2009. From integration to inclusive education: does changing the terms improve practice? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13:553-563. doi: 10.1080/13603110801923476 [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) 1994. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Paris:UNESCO. Available at http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF. Accessed 21 June 2013. [ Links ]

Vlachou A 2004. Education and inclusive policy-making: Implications for research and practice. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 8:3-21. [ Links ]

Walker JC & Evers CW 1999. Research in Education: Epistemology issues. In JP Keeves & G Lakomski (eds). Issues in educational research. Oxford: Elsevier Science. [ Links ]

Wilcox KC & Angelis J 2009. Best practices from high-performing middle schools. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]