Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.33 no.3 Pretoria Jan. 2013

The nature, causes and effects of school violence in South African high schools

Vusumzi Nelson NcontsaI; Almon ShumbaII

ISchool of Post Graduate Studies, University of Fort Hare, South Africa

IISchool of Teacher Education, Central University of Technology. ashumba@cut.ac.za

ABSTRACT

We sought to investigate the nature, causes and effects of school violence in four South African high schools. A purposive sample of five principals, 80 learners and 20 educators was selected from the four schools used in the study. A sequential mixed method approach was used in this study; both questionnaires and interviews were used. The design is divided into two phases, beginning with the collection and analysis of quantitative data, followed by the collection and analysis of qualitative data. The overall purpose of this design is that the qualitative data help explain or build upon initial quantitative results from the first phase of the study. The advantage of the design is that its two-phased nature makes it uncomplicated to implement and to report on. A combination of both quantitative and qualitative methods provides a better understanding of the research problem than either approach alone. A pilot study of the questionnaire was conducted in a school outside the province in which the study was done. Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.72. This was a high positive coefficient and implied that the questionnaire used was reliable. The study found that bullying, vandalism, gangsterism, indiscipline, intolerance, and corporal punishment were prevalent in schools. Furthermore, the study found that school violence had the following effects on learners: loss of concentration; poor academic performance; bunking of classes; and depression. The implications of these findings are discussed in detail.

Keywords: causes, effects, nature, school violence, South Africa

Introduction

Research shows that school violence is escalating despite the measures put in place to address the problem by the Department of Education (DoE) and schools themselves (Fishbaugh, Berkeley & Schroth, 2003; Human Rights Commission, 2006). In their study, Fishbaugh et al. (2003:19) point out that, "Both teachers and students appear justified in fearing for their own safety with the consequence that the learning process is stymied by the need to deal with unruly behaviours and to prevent serious episodes of aggression and violence". Similarly, the Human Rights Commission (2006:1) found: "The environment and climate necessary for effective teaching and learning is increasingly undermined by a culture of school-based violence and this is becoming a matter of national concern". This implies that educators spend most of their time focusing on solving problems associated with school violence instead of focusing on effective teaching and learning. Other studies (Harber & Muthukrishna, 2000; Prins- loo, 2008; Prinsloo & Neser, 2007) also show that the magnitude and effects of violence on teaching and learning is a national concern; this is even more worrying because school violence is escalating despite the measures that have been put in place by the DoE. Harber and Muthukrishna (2000:424) identified violence as a major problem, and said, "A particular problem in many South African schools is that of violence. South Africa is a violent society...". The problems associated with school violence paint a bleak picture of violence in South African schools (Prinsloo, 2008). According to Harber and Muthukrishna (2000:424),

"schools in urban areas, particularly townships are regularly prey to gangsterism. Poverty, unemployment, rural-urban drift, the availability of guns and general legacy of violence has created a context where gangsters rob schools and kill and rape teachers and students in the process".

The above studies confirm that school violence is prevalent in schools.

According to Prinsloo & Neser (2007:47), "school violence is regarded as any intentional physical or non-physical (verbal) condition or act resulting in physical or non-physical pain being inflicted on the recipient of that act while the recipient is under the school's supervision". These physical and non-physical acts of school violence affect teaching and learning negatively because they result in fights and attacks on the victims. Similarly, Crawage (2005:12) describes school violence as "the exercise of power over others in school related settings by some individual, agency, or social process". The government views violence as a serious threat to effective teaching and learning. The above studies showed that school violence negatively affects teaching and learning in schools.

Statement of the research problem

The escalation of violence in South African schools has led researchers to conclude that schools are rapidly and increasingly becoming arenas for violence, not only between pupils but also between teachers and pupils, interschool rivalries, and gang conflict (Prinsloo, 2008; Van Jaarsveld, 2008). Prinsloo (2008:27) stated, "Apart from the serious incidents of school violence that have received wide media coverage, there is general concern regarding the increase in incidents of school violence in South Africa". Due to the high incidence of school violence, schools are no longer viewed as safe and secure environments where children can learn, enjoy themselves, and feel protected (Van Jaarsveld, 2008). Zulu, Urbani, Van der Merwe and Van der Walt (2004:173) conclude that, "Schools have become highly volatile and unpredictable places. Violence has become a part of everyday life in some schools". Reports on television and in the print media highlight the escalation of school violence, such as learners assaulting and stabbing other learners and educators.

In his study of school violence in South African schools, Burton (2008) found that about 1.8 million of all pupils between Grade 3 and Grade 12 (15.3%) had experienced violence in one form or another. Burton (2008) found that 12.8% of the learners had been threatened with violence; 5.8% had been assaulted; 4.6% had been robbed; and 2.3% had experienced some form of sexual violence at school. The above findings clearly show that learners are victims of school violence because it takes place in the classroom or on the school grounds. It is against this background that this study sought to investigate the following: (a) What forms of violence are prevalent in schools?; (b) What are the causes of violence in schools?; and (c) What are the effects of violence on learners and educators?

Method

Research design

A sequential mixed method approach was used in this study. The design is divided into two phases. This design begins with the collection and analysis of quantitative data followed by the collection and analysis of qualitative data (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007). The overall purpose of this design is that the qualitative data help explain or build upon initial quantitative results from the first phase of the study (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007). The advantage of this design is that its two-phased nature makes it uncomplicated to implement and to report on. A combination of both quantitative and qualitative methods provides a better understanding of the research problem than either approach alone (De Vos, Strydom, Fouché & Delport, 2011).

Sample

A purposive sample of five principals, 20 educators and 80 learners was used in this study. The sample was purposively selected from four schools in the Buffalo City district in the Eastern Cape province.

Instruments

Questionnaires and interviews were used to collect data on educators' and learners' experience of school violence. The questionnaires comprised both close-ended and open-ended questions.

Data collection

The purpose of the study was explained to the participants before they completed the questionnaire. The main researcher administered the questionnaire to 20 learners per school with the assistance of educators. All 80 learners returned the completed questionnaires. Interviews were conducted with five educators and four learners who served in the Representative Council of Learners (RCL) because they were familiar with the problems faced by their schools in the resolution of school violence. Data from interviews were captured using a tape recorder.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using percentages and tables. Qualitative data were coded to develop units, themes, sub-themes, and categories. The analysed data were taken back to the participants during the study to check if their responses were correct. All the participants interviewed confirmed as correct their responses used in the study.

Trustworthiness

All participants were assured that all data collected during interviews was confidential and would only be used for purposes of the study. In order to ensure validity of the interviews used, data and tentative interpretations of this study were taken back to the participants during the study to check with them if their responses were correctly captured. All the participants interviewed confirmed as correct their responses used in the study. On the basis of checking with participants if their responses were captured correctly, researchers were confident that the study had high internal validity. The questionnaire was pilot studied to an equivalent sample of 20 learners. Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.72, implying that the questionnaire used was reliable. In order to ensure that the language used was clear to the participants, the questionnaire was edited by two language specialists. Only minor modifications were suggested and these were implemented in the modified questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

Permission to conduct this study was authorised by the University Ethics Committee where the study was carried out. Permission to administer the questionnaire and to interview both learners and educators was sought from the DoE and the district office, and later from the principals of the schools involved in the study, and was granted. Participants were guaranteed anonymity and that the information gathered from them would be kept confidential and only be used for purposes of this study. Since the learners were minors, informed consent was sought from their parents or guardians before involving them in the study. The learners also signed consent forms after written consent was granted by their parents or guardians.

Results

The results of this study are presented using themes and frequency tables. Learner participants' understanding of school violence

The learners gave various accounts of school violence and what they understood as school violence. Learners gave convincing accounts of their conceptualisation of school violence. For example, a learner from School A described school violence as follows: "I think that school violence refers to things that happen at school, like students assaulting each other, stabbing and shooting each other and also educators being assaulted by learners". Similarly, an educator from school D described school violence as, "...lawlessness, disorder and any unethical behaviour that induces fear, uneasiness and intimidation on both learners and educators - the element of fear is so disruptive that it negatively impacts on learning and teaching". Both of these definitions of school violence reveal the seriousness of the problem in South African schools and how it impacts on teaching and learning.

A learner from School B said, "School violence it's whereby learners are bullying, and teachers are doing corporal punishment to the learners...". An educator from school A described school violence as a "Physical attack or harm on people at school, that is, learners, educators and non-teaching staff". It appears from the accounts of the respondents that their views are more or less the same with regard to the forms of school violence in schools.

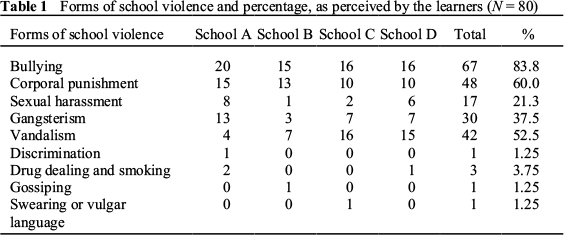

The nature of violence experienced or witnessed by learners and educators in schools All the learners in School A identified bullying as a major problem in their school. For example, the four schools - with 20 learners in School A, 15 learners in School B, 16 learners in School C, and 16 learners in School D - identified bullying as the most common form of violence. This translates to over 67 (83.8%) of the participants reporting that bullying is prevalent in their schools (see Table 1). An educator from School C confirmed this by saying: "Bullying is most common in our school. The bullies take money from other kids, eat their lunch and when the learners don't have money or lunch they are beaten and harassed". Based on the findings in Table 1, most learners perceive bullying, corporal punishment, vandalism, gangsterism and sexual harassment, respectively, as the most prevalent forms of school violence in their high schools.

Table 1 shows that corporal punishment was reported as the second most prevalent form of violence in the four schools. The study found that 48 (60%) of the participants reported that it was practised in their schools. An educator from School B alluded to it as follows: "According to the Constitution corporal punishment by educators is not allowed. As professionals educators are supposed to know the rules and regulations because they are enshrined in the Constitution of the country". An educator from School A acknowledged that "corporal punishment is used by educators in exceptional cases, but I have done my best to stop it because it is unlawful". Despite being banned, the data above show that educators remain the perpetrators of corporal punishment in schools (Maphosa & Shumba, 2010).

The majority of the learners who participated in this study indicated that vandalism is also a major problem in the schools. The same trend was found to prevail in all four of the schools sampled in the Buffalo City district, with participants reporting that they constantly lose their textbooks and calculators due to theft by their peers. An educator from School D said, "Vandalism is very rife in our school. In the past, two six-year olds entered our school, painted everything black and green". In School C, 16 (80%) of the learners reported that vandalism is a major problem in their school. One learner said, "Our calculators and textbooks get stolen and sometimes our books are torn up. Learners break doors and steal door locks". The above findings show that some classes had broken windows and most doors could not be locked as the locks were vandalised. The same observation was true for School D where 15 (75%) of the learners reported that vandalism was common in their school (see Table 1). Table 1 shows that three (3.7%) of the participants reported that drug abuse was prevalent in the schools. The study also found that gangsterism was prevalent and 30 (37.5%) of the participants confirmed that gangs still operated in their schools. The learners reported that gangsterism was a serious problem as their schools were not fenced.

Learners from School A reported that sexual harassment takes place in their school. "There is a lot of sexual harassment taking place at our school. It is the old boys and boys coming from the bush (new initiates) who demand sexual relations with girls. Girls in Grade 9 are normally targeted". The study found that 16 (21%) of the participants had experienced or witnessed sexual harassment at their schools. Table 1 shows that eight (40%) of the participants in School A, and six (30%) in School D reported that sexual harassment is rife in their school. These findings are consistent with literature that the girl child is a victim of sexual harassment (Matsoga, 2003). Other forms of violence reported by the learners from School D included discrimination, drug dealing, smoking, gossiping, and swearing or use of vulgar language. Some learners reported that these forms of violence lead to physical fights among learners in schools. Serious problems such as stabbings and shootings are referred to the police. For example, an educator from School B reported that: "A learner from my school once stabbed an educator and this was reported to the police and SGB [School Governing Body]. The learner was arrested and eventually dismissed".

Effects of school violence as reported by learners and educators

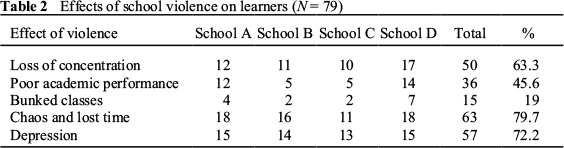

Both learners and educators reported the following as effects of school violence on learners (see Table 2):

Table 2 shows that the majority of the learner respondents believe that school violence causes chaos and leads to loss of learning and tuition time because the disruptions demand that the problems should be attended to. In this study, 64 (79.7%) of respondents reported that when there is a fight in one class, almost all the learners go to witness what is going on. In most cases, the intention by the onlookers would be to cheer those learners involved in the fight. The situation at the school becomes chaotic and educators have to stop the fighting, leading to unnecessary loss of learning and tuition time.

Learners who experience or witness incidents of violence may become depressed and this may affect their ability to learn in a negative manner. The study found that 58 (72.2%) learners reported that they lost concentration because they were afraid of what the perpetrators would do to them during break time or after school. One learner said, "I get worried all the time and I cannot concentrate to my studies. This affects my performance in class and sometimes I feel like not coming to school. I am scared of the bullies".

A substantial number of the learner respondents, 50 (63.3%), reported that they were not able to concentrate on their studies because of school violence (see Table 2). Learners felt threatened by their peers, and sometimes they did things they never intended to do. For example, one of the participants in this study reported that he was once forced to steal by a gang of fellow learners. Fifteen (19%) of the participants ended up bunking classes, and in some cases, learners even dropped out of school because of peer victimisation. For example, 36 (45.6%) of the learner respondents reported that their grades have fallen because of school violence.

High crime rate and violence in communities

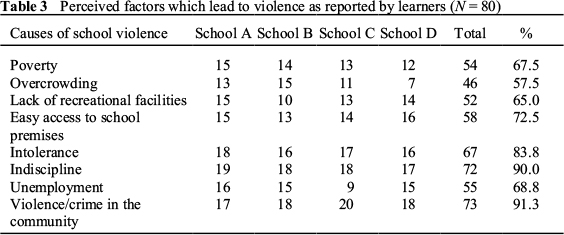

It can be seen from Table 2 that violence in communities is widespread. Over 72 (91%) of the respondents reported that violence in their communities contributed to school violence. For example, a learner from School B reported that: "Violence is very common in our communities and surroundings. This leads to a lot of damage to our schools in that learners come to school carrying weapons and they also indulge in drug abuse". A respondent from School A said that, "Using drugs at school lead to violence. And when other learners talk about you (gossip), it leads to violence". This implied that learners who use drugs at school become violent and violate other learners' rights. This also implies that fights between learners, especially girls, are caused by gossip.

Indiscipline and intolerance

The learners reported that indiscipline is one of the major problems that affect schools negatively. As shown in Table 2, 72 (90%) of the respondents reported that school violence is caused by indiscipline because learners become uncontrollable and do as they wish. Indiscipline affects the school environment, and as a result fighting and ill-behaviour becomes the order of the day. One of the learners from School D said violence is caused by learners, stating that, "When a teacher shouts at him, maybe one of the learners talks back and says you talk rubbish, it is the violence". This type of language is unacceptable on school premises. According to one of the educators, ill-discipline is caused by "disrupted homes and lack of recreational facilities at our schools. As a result of this learners are not engaged all the time. In some instances there is shortage of educators where educators who are on leave are not substituted".

Safety and protection of victims of violence on school premises

Easy access to schools also contributes to the escalation of school violence. Table 2 shows that 58 (72.5%) of the learner participants blamed easy access to schools as a contributing factor in school violence. People from outside easily enter the school premises to conduct business or to commit crime. A learner from School D reported that, "People from outside give learners weapons and bring them to school to make other children afraid". Such situations can lead to fatal accidents. A learner from School B claimed to have witnessed "other learners selling drugs in school. And people from outside come and beat learners in schools". These are incidents of school violence that disturb learners during school hours and as a result some of the learners find it difficult to concentrate on their schoolwork.

Perceived effects of school violence on learning and teaching All the causes of violence identified by the learners range above 50%; this implies that school violence is on the increase. This study (see Table 3) found that 46 (57.5%) of the learner participants reported that poverty contributes to the escalation of violence in schools. A learner from School A, who witnessed a fellow learner who took out a knife and robbed another learner on the school premises, said, "I saw one of the learners taking out a knife and threatening him, demanding money". This incident was blamed on learners who come to school with dangerous weapons and who use drugs. Poverty also contributes to school violence. Unemployment is linked to poverty and 55 (68.8%) of the learners who participated in this study asserted that unemployment causes school violence. A learner from School A said, "I believe that students involve themselves in violence because of poverty, stress and depression". A learner from School B said, "Poverty can cause violence because if a learner is hungry the learner can steal other's lunch; when you find out who took your lunch you will be beaten by him/her and it could lead to violence".

Some learners also ascribed violence in schools to overcrowded classes. For example, 46 (57.5%) of the participants reported that overcrowded classes contributed to school violence. This was also confirmed by the educators. Educators from School A said overcrowded classes are difficult to control and learners tend to misbehave without being detected, and this affects teaching and learning. The lack of recreational facilities was also identified as one of the major causes of school violence, with 65 (65%) of the learner participants confirming this assertion. If there were adequate facilities, then learners who do not excel in class could be given the opportunity to excel on the sports field and earn respect from their classmates.

Table 3 indicates the following as causes of school violence: violence/crime in the community; indiscipline; intolerance; easy access to school premises; unemployment; poverty; lack of recreational facilities; and overcrowding.

Effects of school violence as perceived by educators

Effects on learning

Educators perceived the following as the effects of school violence on learning: (a) The environment becomes not conducive to learning; (b) There is a lack of effective learning and teaching which leads to poor school attendance and eventually leads to a high failure rate; (c) Learners become uncontrollable and difficult to manage; (d) Time is wasted on conflict resolution meetings instead of learning and teaching; (e) High absenteeism and dropout rate; (f) General lack of discipline at school; (g) Disobedience which leads to non-submission of school tasks or not doing homework; (h) School violence leads to academic performance which is not on par with the goals and aspirations of the school; (i) Learners who are victims of bullying bunk classes and end up dropping out of school; (j) Lack of concentration on the part of the learners because they are scared of the perpetrators; and (k) Poor results and an unpleasant atmosphere in the classroom. Most of the above effects of school violence are common in all of the schools that were investigated in this study.

Effects on teaching

Educators perceived the following as effects of school violence on teaching: (a) No effective teaching takes place when learners are uncontrollable, ill-disciplined, and unmanageable; (b) The morale of the educators becomes very low and educators are completely demotivated. Sometimes, when they go to class, they find the class empty because learners leave school during tuition time; (c) The educators find it difficult to complete the syllabus because of poor attendance by learners and the fact that time is wasted on resolving problems emanating from school violence; (d) There are no textbooks because the rate of theft is very high and books and school property are deliberately damaged by unruly learners and this negatively affects teaching; (e) The effect of school violence is reflected by the dilapidated buildings which have been vandalised; the environment is not conducive to teaching; (f) Lack of respect of learners towards each other results in infighting which affects teaching. Learners are always at loggerheads and the atmosphere in the classroom is unbearable; (g) Poor classroom attendance by educators who are not only demotivated but also scared of being attacked by learners; (h) Educators go to class unprepared because they never know what is going to happen the next day; (i) Educators cannot take any decisive action against troublesome learners because they fear for their own safety; (j) School violence affects teaching in a negative way; (k) Teaching is affected because educators feel helpless, demoralised, and disillusioned; (l) School violence disturbs school programmes and the goals and aspirations of the school end up not being achieved; and; (m) School violence leads to a lack of respect for the elderly and education officials due to the unruly behaviour of the learners. The above findings show that school violence has various effects on learning and teaching in our schools.

Violence in some schools has dropped because of the involvement of a nongovernmental organisation (NGO). An educator from School B said, "Violence at our school has dropped tremendously and this may be due to the fact that there is political stability in the community in which our school operates". The same school also reported that the NGO, involved in a project known as Building Safer Schools, had made an immense contribution to fighting school violence. The project involves members of the police force and School Management Team (SMT) members, and as a result, there is heightened police visibility in the area. The school reported that all these efforts have made a major contribution to its academic performance because for the first time in five years the pass rate in Grade 12 was above 60%.

Discussion

Most learners had a clear understanding of the forms of school violence prevalent in their schools. Their description of school violence is consistent with the description of school violence by Crawage (2005) that school violence can be physical and emotional and involves the exercise of power over others by a single person or group of people.

Forms of school violence in schools

The study revealed that the most common form of violence is bullying; this was confirmed by most learner respondents in their schools. The study revealed that older boys were the perpetrators of this form of school violence. The above findings are consistent with literature (Prinsloo, 2008; Smit, 2007).

Vandalism was found to be a major problem in all the schools investigated in this study. This finding is consistent with the literature (Matsoga, 2003; Prinsloo & Neser, 2007). A study conducted by Matsoga (2003:116) found that,

"There was a definite lack of concern on the part of students over property vandalized by their peers. Some students suffered extreme emotional distress over the loss of irreplaceable property such as lecture notes, student files, as well as personal belongings".

The majority of the learners blamed older learners, especially boys, as the alleged perpetrators of violence in schools. The study also revealed that new initiates (amakrwala) are a problem in many schools because they force themselves on girls. The initiates also bully young boys. The problem is so serious that the police have been called to intervene. Some learners said they were scared of going out during break time and after school because the perpetrators and their friends from the community would wait for them outside the school gate. For many learners going to school was no longer enjoyable because they were exposed to many forms of school violence. The study also found that educators were the major perpetrators of corporal punishment in schools. This finding is consistent with the findings of a study conducted by Human Rights Watch (2008).

In addition, the study found that young learners, especially those in Grades 8 and 9, were vulnerable to school violence. By virtue of their age, these young learners cannot defend themselves against bullies. Girls are also targeted by the perpetrators because they are more vulnerable due to being physically weaker. Harber (2001) reported that many children in South Africa were born and bred in violent situations and are used to violence. Chabedi (2003) also reported that violent behaviour has become a norm for many South African young people because during the apartheid era it was used to defy and destroy apartheid. The same scenario was reported by learners and educators who participated in this study. For example, learners bring dangerous weapons to school and attack each other and educators using these weapons. Literature concurs with the above findings (Harber, 2001; Lockhat & Van Niekerk, 2000; Prins-loo, 2008).

The safety of learners and educators can no longer be guaranteed in our schools (Bucher & Manning, 2003). School violence presents educators with many challenges and is now a threat to teaching as a profession. Smit (2007:53) noted, "Securing the school premises and being strict about who is admitted to the school grounds is a practical problem that demands practical solutions". The researchers observed that the schools visited had no security checks and that this puts valuable teaching aids, such as computers, at risk.

The study found that learners bring dangerous weapons to school and use them to attack other learners. Learners are vulnerable to attacks from their fellow learners who terrorise them on the school premises. The guidelines and rules on the safety of learners and educators clearly stipulate that schools are gun-free zones and dangerous weapons are not permissible on the premises. These guidelines and rules appear to be disregarded because learners and educators continue to be attacked within the school premises. Easy access to schools by outsiders makes learners and educators easy victims of people who enter the premises unnoticed and leave after assaulting learners or educators, or selling drugs. The above findings are consistent with literature (De Wet, 2006; Van Jaarsveld, 2008).

Indiscipline results in school violence and makes the school environment non-conducive to learning and teaching. Indiscipline can be linked to chaos and loss of time, hence no effective teaching and learning can take place. For example, the majority of the learner respondents in this study reported that a great amount of time was lost whilst trying to resolve violence related problems. Garegae (2008) concurs with these findings.

Most educators in South Africa have been exposed to the situations described above. It is inconceivable that a learner could stab or shoot a classmate and come back and sit in the same classroom with him or her. Educators who participated in this study were not happy with the rules and regulations imposed by the DoE. Vally, Dolombisa and Porteus (2002:85) found that, "The rampant violence against students and school staff has been pervasive, disruptive and has severely impeded South Africa's schools in their efforts to improve education and address issues of equity in communities where it is most needed". This suggests that the effect of school violence on learning and teaching is devastating and, as a result, the educational goals of schools cannot be attained.

In addition, educators are forced to deal with large classes of more than 60 learners in one class. Both learners and educators reported that overcrowded classes are a problem because misbehaviour goes unnoticed and the rate of theft is very high. Furthermore, the educators reported that overcrowded classes are difficult to control and this impacts negatively on the academic performance of learners. Literature available (De Wet, 2006; Matsoga, 2003) supports the above findings.

Causes of school violence

The study revealed the following as causes of school violence: violence/crime in the community; indiscipline; intolerance; easy access to school premises; unemployment; poverty; lack of recreational facilities; and overcrowding. Studies available on the causes of school violence support the above findings (Harber & Muthukrishna, 2000; Prinsloo, 2008; Prinsloo & Neser, 2007; Van Jaarsveld, 2008).

Effects of school violence on learning and teaching

The learners interviewed reported that bullying affects them negatively. The study also found that school violence had the following effects on learners: poor academic per- formance; bunking of classes; chaos and lost time; and depression. These findings concur with the literature (De Wet, 2006; Prinsloo, 2008; Smit, 2007).

Conclusion

This study investigated the nature, causes and effects of school violence on schools. The study revealed that school violence is a global problem that requires an integrated approach where educators, parents and learners work together.

The study found that bullying, vandalism, gangsterism, indiscipline, intolerance, and corporal punishment were the most prevalent forms of school violence in schools. It also found that school violence had the following effects on learners: loss of concentration; poor academic performance; bunking of classes; chaos and lost time; and depression. All these causes of school violence have a negative impact on learning and teaching.

Recommendations

Based on the findings, the following recommendations should be implemented in order to reduce school violence:

- It is recommended that schools should educate learners, educators and parents about these forms of violence prevalent in schools. Schools could conduct awareness seminars and workshops on the above-mentioned forms of school violence. Learners should be taught to tolerate others through teamwork during lessons.

- Since some boys have been found to be perpetrators of school violence, young learners or victims should be encouraged to report their perpetrators to the school authorities. Any learner found bullying other learners should be disciplined by the school. The school should make the parents aware of their child's bullying before the child is suspended from classes.

- In order to protect schools against gangsterism and vandalism, more personnel should be employed to monitor entrances to schools.

- Any teachers found using corporal punishment on learners should be charged in a court of law since corporal punishment is banned in South African schools.

References

Bucher KT & Manning ML 2003. Challenges and suggestions for safe schools. The Clearing House, 76:160-164. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/30189817.pdf?acceptTC=true. Accessed 10 June 2013. [ Links ]

Burton P 2008. Dealing with school violence in South Africa. Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention (CJCP) Issue Paper, 4:1-16. Available at http://www.cjcp.org.za/admin/uploads/Issue%20Paper%204-final.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2013. [ Links ]

Chabedi M 2003. State power, violence, crime and everyday life: A case study of Soweto in post-apartheid South Africa. Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture, 9:357-371. doi: 10.1080/1350463032000129975 [ Links ]

Crawage M 2005. How resilient adolescent learners in a township school cope with school violence: A case study. Unpublished PhD thesis. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. Available at https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10210/864/margaret.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 10 June 2013. [ Links ]

Creswell JW & Plano Clark VL 2007. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [ Links ]

De Vos AS, Strydom H, Fouché CB & Delport CSL 2011. Research at grass roots for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

De Wet C 2006. School violence in Lesotho: The perceptions, experiences and observations of a group of learners. South African Journal of Education, 27:673-689. [ Links ]

Fishbaugh MSE, Berkeley TR & Schroth G 2003. Ensuring safe school environments: Exploring Issues-Seeking Solutions. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates. [ Links ]

Garegae KG 2008. The crisis of student discipline in Botswana schools: An impact of culturally conflicting disciplinary strategies. Education Research and Review, 3:48-55. Available at http://www.ubrisa.ub.bw:8080/jspui/bitstream/10311/523/1/Garegae_ERR_2008.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2013. [ Links ]

Harber C 2001. Schooling and violence in South Africa: Creating a safer school. Intercultural Education, 12:261 -271. [ Links ]

Harber C & Muthukrishna N 2000. School effectiveness and school improvement in context: The case of South Africa. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 11:421-434. [ Links ]

Human Rights Commission 2006. Report of public hearing on school-based violence. Johannesburg: Human Rights Commission. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch 2008. A violent education: Corporal punishment of children in US public schools. New York: Human Rights Watch. Available at http://www.refworld.org/docid/48ad205f2.html. Accessed 10 June 2013. [ Links ]

Lockhat R & Van Niekerk A 2000. South African children: A history of adversity, violence and trauma. Ethnicity & Health, 5:291-302. doi: 10.1080/135573500200009320 [ Links ]

Maphosa C & Shumba A 2010. Educators' disciplinary capabilities after the banning of corporal punishment in South African schools. South African Journal of Education, 30:387-399. [ Links ]

Matsoga JT 2003. Crime and school violence in Botswana secondary school education: The case of Moeding Senior Secondary School. Unpublished PhD thesis. USA: Ohio University. Available at http://etd.ohiolink.edu/send-pdf.cgi/Matsoga,%20Joseph%20T.pdf?acc_num=ohiou1070637898. Accessed 11 June 2013. [ Links ]

Prinsloo J 2008. The criminological significance of peer victimization in public schools in South Africa. Child Abuse Research, 9:27-36. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/carsa/ carsa_v9_n1_a4.pdf. Accessed 11 June 2013. [ Links ]

Prinsloo J & Neser J 2007. Operational assessment areas of verbal, physical and relational peer victimisation in relation to prevention of school violence in public schools in Tshwane South. Acta Criminologica, 20:46-60. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/crim/ crim_v20_n3_a5.pdf. Accessed 11 June 2013. [ Links ]

Smit E 2007. School violence: Tough problems demand smart answers. Child Abuse Research in South Africa, 8:53-59. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/carsa/ carsa_v8_n2_a1.pdf. Accessed 11 June 2013. [ Links ]

Vally S, Dolombisa Y & Porteus K 2002. Violence in South African schools. Current issues in comparative education, 2:80-90. [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld L 2008. Violence in schools: A security problem? Acta Criminologica, CRIMSA Conference Special Edition (2):175-188. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/crim/ crim_sed2_2008_a12.pdf. Accessed 11 June 2013. [ Links ]

Zulu BM, Urbani G, Van der Merwe A & Van der Walt JL 2004. Violence as an impediment to a culture of teaching and learning in some South African schools. South African Journal of Education, 24:170-175. Available at http://www.ajol.info/index.php/saje/article/viewFile/24984/20667. Accessed 11 June 2013. [ Links ]