Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.33 n.2 Pretoria Jan. 2013

Callings, work role fit, psychological meaningfulness and work engagement among teachers in Zambia

Sebastiaan RothmannI; Lukondo Hamukang'anduII

IOptentia Research Programme, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa ian@ianrothmann.com

IIUniversity of Namibia, Windhoek

ABSTRACT

Our aim in this study was to investigate the relationships among a calling orientation, work role fit, psychological meaningfulness and work engagement of teachers in Zambia. A quantitative approach was followed and a cross-sectional survey was used. The sample (n = 150) included 75 basic and 75 secondary school teachers in the Choma district of Zambia. The Work Role Fit Scale, Work-Life Questionnaire, Psychological Meaningfulness Scale, and Work Engagement Scale were administered. Structural equation modelling confirmed a model in which a calling orientation impacted psychological meaningfulness and work engagement significantly. A calling orientation impacted work engagement directly, while such work orientation impacted psychological meaningfulness indirectly via work role fit. The results suggest that it is necessary to address the work orientation and work role fit of teachers in Zambia as pathways to psychological meaningfulness and work engagement.These results have implications for the recruitment, selection, training, and development of teachers in Zambia.

Keywords: Africa, calling, engagement, meaning, teachers, work role fit

Introduction

Education is regarded as one of the cornerstones of development in Zambia. However, the learning society, culture, knowledge base and intellectual potential in the country may be endangered by poverty, unemployment, exploitation and disease (Alexander, 2006). According to Alexander (2006), there has been an overall increase in poverty in Zambia since 1991, which has resulted in political, economic, social and cultural chaos. Education in Zambia has been in disarray because of changes in the country and pressure on the learning society. Although education was a high-status and well-remunerated profession before 1991, Zambian teachers are now paid substantially less compared to other civil servants, have poor or inadequate housing, receive few incentives and have few development and promotion opportunities (Alexander, 2006). Bajaj (2009) reported that teachers in Zambia often supplement their income by taking on additional jobs that result in their absence at work. Poor management in government schools makes it difficult to take corrective action when teachers perform poorly (Bajaj, 2009). Many schools are also understaffed because of the loss of teachers due to Human Immunosuppresive Virus (HIV)/AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) and the economic downturn. In the long run many teachers build up frustration,- loose meaning and purpose at work and become disengaged from their work (Kelly, 1999).

Psychological meaningfulness at work is an important topic in the debate about education, given that human beings are essentially spiritual beings. De Klerk-Luttig (2008) refers to the concept of spiritual stuntedness which results in an absence of spirituality in teaching. Spiritual stuntedness is characterised by a lack of spontaneity, too much concern with form and appearances and a tendency to shut oneself off from what matters deeply. Spirituality is defined in terms of meaning denoted to life and experiences. Spirituality includes "a sense of transcendence, a sense of calling or being called" (De Klerk-Luttig, 2008:507). A study by Wolhuter, Van der Walt, Potgieter, Meyer and Mamiala (2012) showed that student teachers were inspired by experiences that are psychologically meaningful and engaging.

In spite of the challenging situation in the Zambian education sector (Baj aj, 2009), teachers are still reported to be the most engaged of civil servants in the country (Kelly, 1999). This may be explained by the presence of a calling and psychological meaningfulness that they experience at work. Matuska and Christiansen (2008) assert that psychological meaningfulness is most important for resilience under stressful conditions. Treadgold (1999) found that employees who were more engaged in meaningful work were more intrinsically motivated than employees with a low level of meaningfulness. Furthermore, almost all employees wanted their work to be meaningful (Treadgold, 1999).

Various theoretical models of subjective well-being include the concept of psychological meaningfulness and engagement. For example, Seligman (2002) identified three orientations towards well-being, namely, pleasure, engagement, and meaning-fulness. Engagement and psychological meaningfulness (compared to pleasure) are considered to be more under the control of the individual and lead to longer lasting fulfilment (Peterson, Park & Seligman, 2007; Seligman, 2002). Experiences of psychological meaningfulness and engagement at work are po sitively associated with satisfaction with life, job satisfaction, organisational commitment, organisational citizenship behaviour and low turnover intention (Swart & Rothmann, 2012). Studies by Kahn (1990) and May, Gilson and Harter (2004) showed that work roles and activities which are aligned with individuals' self-concepts are associated with more psychologically meaningful work experiences, which also impact individuals' work engagement positively.

Teachers, like the majority of employed people (Wrzesniewski, McCauley, Rozin & Schwartz, 1997), spend a large part of their day at work and more than 88% of this working time is spent in interactions with other people. Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler and Tipton (1985) assert that the effect of meaning of work is especially visible in an occupation where individuals are constantly interacting with various social systems within an organisation, for example in education. Teachers are primary role models for happiness (engagement and psychological meaningfulness) in the- workplace. Unfortunately, teachers often experience high levels of job stress, which negatively impact their meaningfulness and work engagement (George, Louw & Badenhorst, 2008; Schulze & Steyn, 2007). According to De Klerk-Luttig (2008:513), a school should be an environment where the emphasis falls on "being" rather than doing. This can be done by focusing on psychological meaningfulness and work engagement.

Work engagement and psychological meaningfulness

Work engagement has been defined as a fulfilling, positive, work-related state of the mind that is characterised by dedication, absorption and vigour (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Kahn (1990:694) defines work engagement as the harnessing of members' selves, in the organisation, to their work roles so "... that they employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, mentally and emotionally during role performance". When people display their preferred selves at work, it can be said that they display their real thoughts, feelings and identity.

Psychological meaningfulness is the significance one attaches to one's existence and encompasses the value one places on the existence of life and on the course of his/her life (Taubman-Ben-Ari & Weintroub, 2008). According to Frankl (1985), individuals have the freedom to find meaning in their lives and have the freedom to choose and detect meaning in even the most basic of life's moments. Individuals experience psychological meaningfulness at work when they experience that they are receiving a return on investment of the self in a currency of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive rewards. Psychological meaningfulness (defined as the significance a person attaches to something) is related to work engagement. In an organisation, people are most likely to experience psychological meaningfulness when they feel they are useful, valuable and worthwhile (Kahn, 1990; May et al., 2004).

Rosso, Dekas and Wrzesniewski (2010) point out that two related concepts regarding meaningful work, namely, "meaning" and "meaningfulness", are often used in the literature. Rosso et al. (2010) define psychological meaningfulness as the amount of significance a job has for the individual. Meaning of work refers to the type of meaning (rather than the amount of significance) that a job has (e.g. work as a calling). Experiences of psychological meaningfulness as well as meaning of work result in positive work-related outcomes (May et al., 2004; Olivier & Rothmann, 2007; Wrzesniewski, 2012).

Isaksen (2000) found that it is even possible to construct meaning in repetitive work. In his study, he found that 75% of employees in repetitive work overall find their work life meaningful and 82% would continue to work even if they could receive the same salary for staying at home. According to Isaksen (2000), psychological mean-ingfulness and meaninglessness are not just effects of some specific working conditions but a result of individuals' spontaneous and continuous effort to find meaning, no matter what kinds of conditions they endure.

Two factors which seem relevant for the development of psychological meaning-fulness and work engagement are work beliefs (Wrzesniewski, Dekas & Rosso, 2009) and work role fit (Kahn, 1990; May et al., 2004).

Calling as a work belief

Meaning of work is the set of beliefs that an individual holds about work which results in experiences of psychological meaningfulness. These beliefs are acquired through one's interaction with the social environment. Bellah et al. (1985) propose that employees view their work as a career, or a job or a calling. A calling orientation to work is what most employers would like to foster in their employees, as it offers a special fulfilment and meaning to one's work and yields positive work behaviour (Wrzes-niewski et al., 1997). A calling has been defined as a "meaningful beckoning toward activities that are morally, socially and personally significant" (Wrzesniewski et al., 2009:181). People with a calling orientation to work do not seek financial reward; they work for the fulfilment they get from the work itself. Such people view their work as an end in itself and not a means to an end.

According to Hirschi (2012), callings should be regarded as an antecedent to psychological meaningfulness at work because a calling provides a person with a sense of purpose in his or her work, which enhances the perception of one's work as meaningful. Duffy, Bott, Allan, Torrey and Dik (2012) confirmed that the presence of a calling predicted experiences of psychological meaningfulness at work. Psychological meaningfulness is an important predictor of work engagement (May et al., 2004). Increased psychological meaningfulness at work seems to be an important reason why callings are related to work engagement.

The calling orientation develops in conjunction with the work one is doing, so it is not entirely internally rooted (Rosso et al., 2010). Callings are unique for each person and are seen as a way for a person to connect with the inner self. It is something that a person believes will fulfil their unique role in life (Rosso et al., 2010; Wrzes-niewski, 2012). According to Wrzesniewski (2012:49), a calling could develop in three ways. First, a person should do introspection to "hear" a calling that is coming from a sacred source. Second, an individual could look deep into the self to discover data that will direct them towards work that will be experienced as deeply meaningful. Third, individuals could be challenged to craft a job which aligns with his or her sense of calling. It should also be noted that callings are not in any way static; they change over time.

According to Wrzesniewski (2012), callings might develop from spiritual sources, the self, an individual's upbringing, role models and work experiences. Based on social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), it could be argued that callings may develop via the imitation of observed behaviours from parents and other models in society, and specifically their orientations to work. Furthermore, individuals are motivated to construct and validate positive identities in their own eyes and the eyes of others- (Roberts & Creary, 2012), which may lead to the development of a calling orientation. Wrzesniewski (2012) asserts that social class (which affects educational opportunities, social networks and opportunity structures) contributes to the development of a calling orientation.

A calling is different from a passion in that a calling typically involves a sense that the work one is doing makes the world a better place, while a passion does not necessarily have a social component to it and is marked with subjective vitality and the experiences of joy (Hirschi, 2011:61). Individuals with a calling orientation put in extra effort and time at work. They display this positive behaviour regardless of whether or not they feel they are receiving adequate compensation for their extra work (Hall & Chandler, 2005; Wrzesniewski et al., 1997; Wrzesniewski, 2012).

Work role fit

The perceived fit between individuals' self-concepts and their roles within the organisation (workrole fit) results in the experience of psychological meaningfulness and engagement (Kahn, 1990; May et al., 2004; Olivier & Rothmann, 2007). Work roles which are aligned with individuals' self-concepts are associated with experiences of psychological meaningfulness (May et al., 2004). Work roles and tasks that are congruent with an individual's values (Waterman, 1993) and/or require the use of an individual's signature strengths (Seligman, 2011) contribute to experiences of work role fit, psychological meaningfulness and work engagement (May et al., 2004).

Human beings are creative and self-expressive and therefore they will look for work roles that will help them express their true self. Individuals will feel more effective in a job that helps them express their true self-concept, where they experience a work role fit (Kahn, 1990). According to Kahn (1990), individuals will experience more psychological meaningfulness and invest more of the self in achieving the goals set out for them by the organisation when they experience greater congruence between the self and the requirements of their work role (May et al., 2004). Van Zyl, Deacon & Rothmann (2010) found that work role fit predicted psychological meaningfulness and work engagement in a sample of industrial psychologists. This is because such individuals see their work as not only a means to an end but as an end in itself; they see their work as a calling (Dik & Duffy, 2008). When the work roles are not fitting their self-concepts, such individuals will re-craft their work to match how they perceive the self (Wrzesniewski, 2003).

Aim and Hypotheses

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationships among work role fit, calling as a work belief, psychological meaningfulness, and work engagement in a sample of teachers in Zambia. Interventions to address a calling orientation and work role fit can be developed and implemented if these factors explain experiences of psychological meaningfulness and work engagement of teachers.

The following hypotheses are formulated based on the discussion of literature findings above:

Hypothesis 1: A calling orientation is positively related to work role fit.

Hypothesis 2: Work role fit is positively related to psychological meaningfulness.

Hypothesis 3: A calling orientation is positively related to psychological meaningfulness.

Hypothesis 4: A calling orientation is positively related to work engagement.

Hypothesis 5: Work role fit is positively related to work engagement.

Hypothesis 6: Psychological meaningfulness is positively related to work engagement.

Hypothesis 7: A calling orientation indirectly affects psychological meaningfulness via work role fit.

Hypothesis 8: A calling orientation indirectly affects work engagement via work role fit.

Method

Research design

A quantitative approach was used in this study. A cross-sectional survey was conducted to gather data to analyse the relationships among variables (Terre Blanche & Durrheim, 1999).

Participants

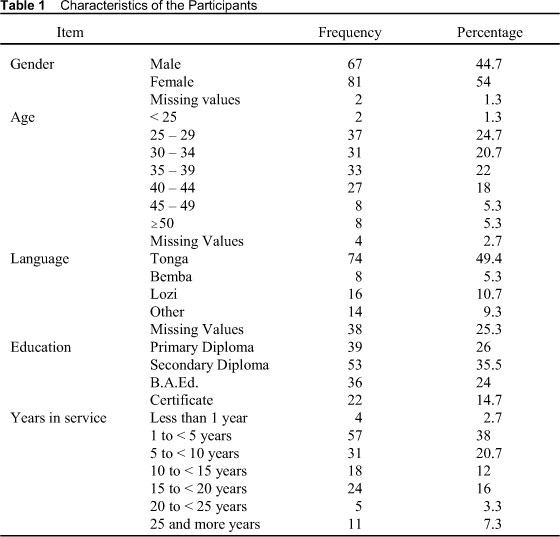

There are approximately 3,500 teachers in the Choma district who teach in the 20 primary schools and 20 secondary schools in the district. Half of the sample were primary school teachers (n = 75) and the other half were secondary school teachers (n = 75). Table 1 highlights the characteristics of the participants.

Table 1 shows 54% of the respondents were female and 24.7% were in the age group 25 to 29 years. The majority of the respondents spoke Tonga. A total of 35.5% of the respondents had secondary school diplomas. A total of 40% of the respondents had been in service for between one and five years.

Measuring instruments

Four measuring instruments, namely, the Work Role Fit Scales, Work-Life Questionnaire, Psychological Meaningfulness Scale and the Work Engagement Scale, were chosen for the empirical study. These instruments were selected because of their acceptable psychometric properties within multicultural contexts.

The Work Role Fit Scale (WRFS; May et al., 2004) was used to measure workrole fit. Workrole fit is measured by averaging four items from May et al. (2004) (e.g. "My job 'fits' how I see myself"). For all items, a Likert scale varying from 1 "never" to 5 "always" was used. Rothmann and Welsh (in press) found evidence for the construct- validity of the WRFS in a study of employees in different organisations in Namibia. Rothmann and Welsh (in press) reported an alpha coefficient of 0.88 for the WRFS.

The Work-Life Questionnaire (WLQ; Wrzesniewski et al., 1997) was utilised to measure teachers' levels of calling as a work belief. Seven items were used to measure a calling orientation. The items were also rated on a Likert scale varying from 1 "not at all" to 4 "completely". An example item is "I find my work rewarding". Van Zyl et al. (2010) found an alpha coefficient of 0.87 in a study of organisation psychologists in South Africa.

The Psychological Meaningfulness Scale (PMS; Spreitzer, 1995) was used to measure psychological meaningfulness by averaging six items. For all items, a Likert scalevarying from 1 "never" to 5 "always" was used. These items measure the degree of meaning individuals discovered in their work-related activities (e.g. "The work I do on this job is very important to me"). Rothmann and Welsh (in press) confirmed the construct validity of the PMS in a study in Namibia. Rothmann & Welsh (in press) reported an alpha coefficient of 0.92 for the PMS.

The Work Engagement Scale (WES; May et al., 2004) was adapted and used to measure work engagement. For all items, a Likert scale varying from 1 "never" to 5 "always" was used. Two subscales of the WES, measuring emotional engagement (four items; e.g. "I really put my heart into my job") and physical engagement (four items; e.g. "I am full of energy in my work"), were used in this study. Rothmann & Welsh (in press) found an acceptable Cronbach alpha coefficient (a = 0.79) for the WES in their study in Namibia.

Research procedure

The respondents were secured through interviews to ascertain their willingness to participate in the research. The data were obtained by giving the questionnaires to the teachers. All the questionnaires were self-report; therefore the questionnaires were collected one day after they were handed out to participants.

Data analysis

The statistical analyses were carried out by means of the SPSS19 program (SPSS Inc., 2009). Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data. Cronbach alphas were used to determine the reliability of the measuring instruments. Pearson correlations were used to specify the relationships between the variables. A cut-off point of 0.30 (medium effect) was set for the practical significance of correlation coefficients (Cohen, 1992). Structural equation modelling methods as implemented in AMOS (Arbuckle, 2008) were used to test the measurement and structural models in this study by using maximum likelihood analyses. The following indices produced by AMOS were used in this study (Hair, Black, Babin & Andersen, 2010): the chi-square statistic Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Indirect effects were assessed using the procedure explained by Hayes (2009).

Results

Descriptive statistics, alpha coefficients and correlations

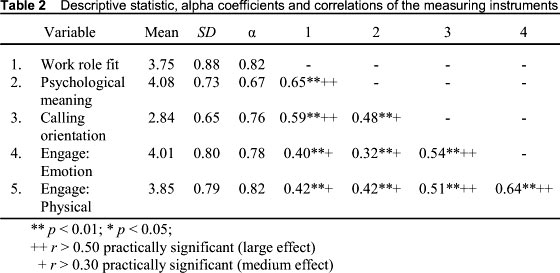

The descriptive statistics, alpha coefficients and correlations of the constructs are reported in Table 2.

Table 2 shows that the alpha coefficients of most of the scales were higher than the 0.70, indicating acceptable internal consistency (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). However, the internal consistency of one scale, psychological meaningfulness, was slightly lower than the recommended value. A total of 26.7% and 24.7% of the- teachers selected the alternatives "very much like me" and "somewhat like me", respectively, when they responded to a statement which describes the characteristics associated with a calling orientation to work. A total of 48.6% of the teachers did not view their work as a calling.

Testing the measurement model

Using confirmatory factor analysis, a hypothesised measurement model of meaning and work engagement was tested to assess whether each of the measurement items would load significantly onto the scales they were associated with. The model consisted of four latent variables, namely a) work orientation calling, measured by seven observed variables; b) work role fit, measured by five observed variables; c) psychological meaningfulness, measured by four observed variables; and d) work engagement, consisting of two latent variables, namely emotional engagement (measured by four observed variables) and physical engagement (measured by four observed variables).

The fit indices indicate that the measurement model fit the data well. A ÷2 value of 313.58 (df = 222,p < 0.01) was obtained for the model. The other fit indices were all higher than the recommended values: TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05 and SRMR = 0.06. Therefore the hypothesised four-factor measurement model had an acceptable fit with the data. The R2 for one item measuring meaning was low (0.10, which means that the latent factor extracted only 10% of the variance in the item). Therefore the item was removed. The fit indices indicate that the adapted measurement model had a ÷2 value of 273.87 (df = 201,p < 0.01). The change in ÷2 was significant (Δ÷2 = 39.71, Adf = 21, p < 0.01). The other fit indices were all higher than the recommended values: TLI = 0.93, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04 and SRMR = 0.05. The standardised coefficients from items to factors ranged from 0.32 to 0.89. Furthermore, the results indicated that the relationship between each observed variable and its respective construct was statistically significant (p < 0.01), establishing the posited relationships among indicators and constructs (see Hair et al., 2010).

Testing the structural model Evaluating the hypothesised model

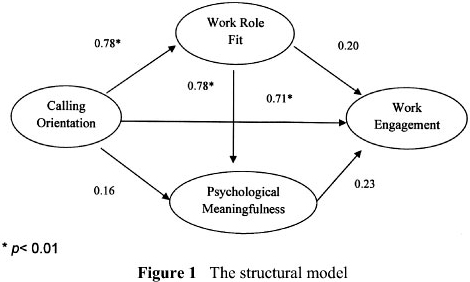

The hypothesised relationships were tested using structural equation modelling as implemented by AMOS (Arbuckle, 2008). Results indicated a fair fit of the structural model compared to the measurement model (÷2 = 273.87, df = 201, TLI = 0.93, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04 and SRMR = 0.05). The standardised regression coefficients are given in Figure 1.

For the portion of the model predicting work role fit, the path coefficient was significant and had the expected sign. Having a calling as work orientation had a strong positive relation with work role fit (R2 = 0.62). Hence hypothesis 1 is accepted. For the portion of the model predicting psychological meaningfulness, the path coefficient of work role fit was significant and had the expected sign. Work role fit has a positive relationship with psychological meaningfulness (R2 = 0.70). These results provide support for hypothesis 2. However, the path coefficient of a calling work orientation was not significant. Hypothesis 3 is rejected. For the portion of the model predicting work engagement, the path coefficient of a calling work orientation was significant and had the expected sign. A calling orientation had a strong positive relation with work engagement (R2 = 0.61). Hence hypothesis 4 is accepted. However,- the path coefficients of work role fit and psychological meaningfulness on work engagement were not significant. Hypotheses 5 and 6 are therefore rejected.

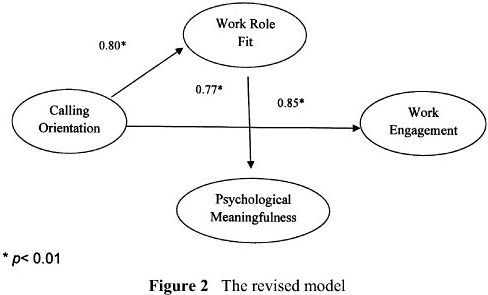

Revised model

To test the last two hypotheses, three insignificant paths in the structural model were removed, i.e. the path from a calling orientation to psychological meaningfulness, the path from work role fit to work engagement, and the path from psychological mean-ingfulness to work engagement. The revised model showed acceptable fit: X2 = 276.82, df = 204, TLI = 0.93 CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04 and SRMR = 0.05. The nonsignificant chi-squared difference tests, after these path deletions, indicated that the removal of these paths did not significantly impact the model's degree of overall fit (Δ÷2 =2.95, Δdf = 3,p > 0.01). The revised model is shown in Figure 2.

To determine whether the relationship between a calling orientation and psychological meaningfulness was indeed mediated by work role fit, the procedure explained by Hayes (2009) was used. Bootstrapping was used to construct two-sided bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) so as to evaluate mediation effects. Lower CIs (LCIs) and upper CIs (UCIs), effects and standard errors (SE) were analysed. The bias-corrected confidence intervals for work role fit did not include zeros (effect = 0.33, SE = 0.05, LCI = 0.23, UCI = 0.44). Therefore, work role fit mediated the relationship between a calling work orientation and experiences of psychological meaning-fulness at work. Hence hypothesis 7 is accepted. The path from work role fit to work engagement was not significant. Therefore hypothesis 8, which states that a calling orientation indirectly affects work engagement, is not accepted.

Taken together, the model fit indices suggest that the relationships posited in the revised model account for a substantial amount of the covariation in the data. The revised model accounts for a large proportion of the variance work role fit (64%), work engagement (60%) and psychological meaningfulness (72%).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationships among work role fit, work beliefs, psychological meaning and work engagement in a sample of teachers in Zambia. A total of 26.7% of Zambian teachers in this study reported a strong calling orientation to their work, while 48.6% of the teachers did not feel a strong calling. The present study enhances our understanding of the relationships between a calling work orientation, work role fit, psychological meaningfulness and work engagement. The results support the theoretical model that callings have positive outcomes because they affect the perceptions of work role fit.

As suggested by the findings, a calling orientation and work role fit allow people to more often experience psychological meaningfulness and work engagement (i.e. vitality and dedication). The results confirm the theoretical link between a calling and meaningful work (Hirschi, 2012; Wrzesniewski, 2012) and support the assumption that a calling work orientation is an important factor in understanding what makes work meaningful and engaging (Hirschi, 2012; Rosso et al., 2010). The findings suggest that work role fit is an important factor in understanding the relation between a calling work orientation and experiences of psychological meaningfulness at work. Given the importance of education to establish and maintain a learning culture in Zambia, our results suggest that it is necessary to address the work orientation and work role fit of teachers in Zambia as pathways to psychological meaningfulness and work engagement.

The structural model in this study showed that having a calling orientation towards work has direct and indirect effects on work role fit, psychological meaningfulness and work engagement. It seems that a calling orientation impacts psychological meaning-fulness of teachers in Zambia indirectly via work role fit. Therefore teachers will experience psychological meaningfulness when they fit in their roles (Van Zyl et al., 2010). A calling orientation also directly and strongly impacted work engagement. The teachers in Zambia who participated in this study experienced psychological mean-ingfulness at work when they viewed their work as a calling and this relationship was mediated by the perception that their work roles fit how they view themselves. The results also showed that the teachers with a calling orientation displayed vitality and dedication at work.

The study of Van Zyl et al. (2010) also showed that psychological meaningfulness and work engagement are strongly affected by a calling orientation. Contrary to the findings of Van Zyl et al. (2010), work role fit did not predict work engagement of teachers in Zambia. Although psychological meaningfulness was related to work- engagement, this relationship was not significant in the structural model. This finding is attributed to the effects of the strong relationship between a calling orientation and work engagement. Although Zambian teachers who have a calling orientation (compared to those who have less of a calling orientation) experience better work role fit (and consequently find their work more meaningful and significant), our findings suggest that they engaged at work irrespective of whether they perceived that they fit into their work roles and their experiences of psychological meaningfulness at work. A lack of psychological meaningfulness can be the result of poor working conditions, a poor fit between worker interests and job opportunities, or a lack of belief in one's own attempts to construct meaning (Isaksen, 2000). In line with the perspective of Seligman (2011), psychological meaningfulness and work engagement might be two different components of well-being of people.

When teachers view their work as callings, they experience work role fit and they perceive their work experience as being psychologically meaningful. Additionally, because of the callings, they are engaged in their work. Teachers who experience work role fit perceive their work as an opportunity to express their true selves in their work, which results in psychological meaningfulness (May et al., 2004). Having a calling orientation to work seems to contribute to people extending their work roles to the selves because they perceive that they are in work roles that are congruent to their self-concepts. The identity one's work gives will be readily assumed by teachers if it fits how they see themselves (Kahn, 1990; May et al., 2004).

When the work roles of teachers do not fit their self-concepts, teachers with a calling orientation might re-craft their work to match how they perceive the self (Wrzesniewski, 2003). Berg, Dutton and Wrzesniewski (2008) assert that there are three main ways in which employees can re-craft their work: a) by reframing the societal rationale of their work; b) by taking on additional work that is more closely related to that which they like; and c) by giving more time, energy and attention to tasks that provide meaning and engage them. Job crafting is an effective tool for coping with organisational stress and other work pressures. Therefore it is important for the organisation to leave room for teachers to craft their work. But educational managers should also monitor the situation so that the extra work that the teachers take on does not lead to burnout.

This study had various limitations. First, the study utilised a cross-sectional design, which does not allow investigating the developmental effects and patterns that link callings with work role fit, psychological meaningfulness and work engagement. A disadvantage of the cross-sectional design is that it is primarily influenced by the mean population trends while overlooking other influencing variables. Longitudinal studies should be conducted to determine causal effects and the changes in the conceptualisation of meaning of work for teachers in Zambia. Second, self-reports that were used induce common method variance, which may have affected the observed relationship among the measures. Third, although the constructs studied were distinct,- they showed a considerable overlap as indicated by their moderate to high correlations. Future research should establish whether the calling construct is unique and has incremental validity beyond the other constructs included in this study. Fourth, the sample was restricted to primary and secondary school teachers in one district in Zambia. It is important for future studies to investigate the proposed model within different demographic groups in southern Africa.

Recommendations

Based on the results of this study, educational managers can on average assume that, within a given job, individuals with a calling orientation would experience more psychological meaningfulness and work engagement. Because this study uncovered more closely why callings have beneficial outcomes, the results also have implications for how to obtain the benefits typically associated with callings for teachers who do not experience a calling. It is recommended that coaching and workshops be used to help teachers find their calling (Dik & Duffy, 2008). A second approach might be to directly enhance teachers' work role fit in order to increase their psychological meaningfulness, regardless of whether or not they report a calling. Human resource management initiatives (including recruitment, selection, induction, training and development and performance management) should be implemented to promote work role fit of teachers, which will result in psychological meaningfulness and work engagement (Isaksen, 2000). Teachers and educational institutions should be made aware of the concept of job re-crafting and should implement interventions to promote job crafting.

References

Alexander D 2006. Beyond a learning society? It is all to be done again: Zambia and Zimbabwe. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 25:595-608. [ Links ]

Arbuckle JL 2008. Amos 17.0. Crawfordville, FL: AMOS Development Corporation. [ Links ]

Bajaj M 2009. Why context matters: the material conditions of caring in Zambia. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22:379-398. Available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2143435. Accessed 13 March 2013. [ Links ]

Bandura A 1977. Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press. [ Links ]

Bellah R, Madsen R, Sullivan W, Swidler A & Tipton S 1985. Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Berg JM, Dutton JE & Wrzesniewski A 2008. Theory-to-practice briefing: What is job crafting and why does it matter? United States of America: Center for Positive Organizational Scholarship, Ross School of Business, University of Michigan. Available at www.bus.umich.edu/positive/pos-teaching-and-learning/job_crafting-theory_to_practice-aug_08.pdf. Accessed 13 March 2013. [ Links ]

Cohen J 1992. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112:155-159. [ Links ]

De Klerk-Luttig J 2008. Spirituality in the workplace: A reality for South African teachers? South African Journal of Education, 28:505-517. [ Links ]

Dik BJ & Duffy RD 2008. Calling and vocation at work: Definitions and prospects for research practice. The Counselling Psychologist, 8:48-61. [ Links ]

Duffy RD, Bott EM, Allan BA, Torrey CL & Dik BJ. 2012. Perceiving a calling, living a calling, and job satisfaction: Testing a moderated, multiple mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59:50-59. [ Links ]

Frankl VE 1985. Man's search for meaning. New York: Washington Square Press Printing. [ Links ]

George E, Louw D & Badenhorst G 2008. Job satisfaction among urban secondary-school teachers in Namibia. South African Journal of Education, 28:135-154. [ Links ]

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ & Andersen RE 2010. Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Hall DT & Chandler DE 2005. Psychological success: When the career is a calling. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26:155-176. [ Links ]

Hayes AF 2009. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76:408-420. [ Links ]

Hirschi A 2011. Callings in career: A typological approach to essential and optional components. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79:60-73. [ Links ]

Hirschi A 2012. Callings and work engagement: Moderated mediation model of work meaningfulness, occupational identity, and occupational self-efficacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59:479-485. doi: 10.1037/a0028949. [ Links ]

Isaksen J 2000. Constructing meaning despite the drudgery of repetitive work. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 40:84-107. [ Links ]

Kahn WA 1990. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33:692-724. [ Links ]

Kelly MJ (ed.) 1999. The origins and development of education in Zambia from Pre-colonial times to 1996. Lusaka: Zambia Education Publishing House. [ Links ]

May DR, Gilson RL & Harter LM 2004. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 77:11-37. [ Links ]

Matuska KM & Christiansen CH 2008. A proposed model of lifestyle balance. Journal of Occupational Science, 15:9-19. [ Links ]

Nunnally JC & Bernstein IH 1994. Psychometric theory (3rd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Olivier AL & Rothmann S 2007. Antecedents of work engagement in a multinational oil company. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 33:49-56. [ Links ]

Peterson C, Park N & Seligman MEP 2007. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6:25-41. [ Links ]

Roberts LM & Creary SJ 2012. Positive identity construction: Insights from classical and contemporary theoretical perspectives. In KS Cameron & GM Spreitzer (eds). The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rosso BD, Dekas KH & Wrzesniewski A 2010. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30:91-127. [ Links ]

Rothmann S & Welsh C 2013. Employee engagement in Namibia: The role of psychological conditions. Management Dynamics, 22(1). [ Links ]

Schaufeli WB & Bakker AB 2004. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 25:293-315. [ Links ]

Schulze S & Steyn T 2007. Stressors in the professional lives of South African secondary school educators. South African Journal of Education, 27:691-707. [ Links ]

Seligman MEP 2002. Authentic happiness. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Seligman MEP 2011. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Spreitzer G 1995. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38:1442-1465. [ Links ]

SPSS Inc.2009. SPSS16.0 for Windows. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc. [ Links ]

Swart J & Rothmann S 2012. Authentic happiness of managers, and individual and organisational outcomes. South African Journal of Psychology, 42(4):492-508. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/sapsyc/sapsyc_v42_n4_a4.pdf Accessed 13 March 2013. [ Links ]

Taubman-Ben-Ari O & Weintroub A 2008. Meaning in life and personal growth among pediatric physicians and nurses. Death Studies,32:621-645. [ Links ]

Terre Blanche M & Durrheim K (eds) 1999. Research in practice: Applied methods for the social sciences. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Treadgold R 1999. Transcendent vocations: Their relationship to stress, depression, and= clarity of self-concept. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 39:81-102. [ Links ]

Van Zyl LE, Deacon E & Rothmann S 2010. Towards happiness: Experiences of work-role fit, meaningfulness and work engagement of industrial/organisational psychologists in South Africa. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36, Art. #890, 10 pages. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v36i1.890 [ Links ]

Waterman AS 1993. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64:678-691. [ Links ]

Wolhuter C, Van der Walt H, Potgieter F, Meyer L & Mamiala T 2012. What inspires South African student teachers for their future profession? South African Journal of Education, 32:178-190. [ Links ]

Wrzesniewski A 2003. Finding positive meaning in work. In KS Cameron, JE Dutton & RE Quinn (eds). The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler. [ Links ]

Wrzesniewski A 2012. Callings. In KS Cameron & GM Spreitzer (eds). The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Wrzesniewski A, Dekas K & Rosso B 2009. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26:179-201. [ Links ]

Wrzesniewski A, McCauley C, Rozin P & Schwartz B 1997. Jobs, careers, and callings: People's relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31:21-33. [ Links ]