Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.32 n.4 Pretoria Jan. 2012

Youth envisioning safe schools: a participatory video approach

Naydene de LangeI; Mart-Mari GeldenhuysII

IFaculty of Education, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, South Africa Naydene.delange@nmmu.ac.za

IINelson Mandela Metropolitan University

ABSTRACT

Gender-based violence is pervasive in South African society and is often seen as the driver of HIV, particularly affecting youth. Rural KwaZulu-Natal, where we have been working in a district in an on-going university-school partnership, is noted as the epicentre of the epidemic. The two secondary schools in this study were therefore conveniently chosen while the 30 Grade 9 learners, 7 boys and 23 girls between the ages of 13-16, were purposively selected. The use of participatory visual methodologies, which is the focus of this special issue, taps into the notion of 'research as intervention' and speaks to the potential of educational research contributing to social change. In this qualitative study we used participatory video to explore youths' understanding of gender-based violence, as well as how they envision making schools safe. Power theory is used as theoretic lens to frame the study and to make meaning of the findings, namely, that girls' bodies are sites for gender-based violence at unsafe schools; that the 'keepers of safety' are perpetuating gender-based violence at school; and that learners have a sound understanding of what can be done to address gender-based violence. This study, with its 'research as intervention' approach, enabled learners to make their voices heard and to reflect on what it is that they as youth can do to contribute to safe schooling.

Keywords: gender-based violence, HIV&AIDS, participatory video, safe schools, youth

Introduction

"It's about being scared, because we all have been scared ..."

Girl Participant, School A

The above quotation by one of the girl participants captures the essence of feeling afraid at school, a place where youth should feel safe. It however also allows us a glimpse into the pervasiveness of being afraid at school (Human Rights Watch, 2001). Considering that South Africa is "one of the most violent societies in the world" (Morrell, Epstein, Unterhalter, Bhana & Moletsane, 2009:34) it could be anticipated that schools will also be affected sites. Barnes, Brynard and De Wet (2012:79), in studying school culture and school climate, point out that "the lack of school safety contributes to learners experiencing higher levels of violence at school" which increases the chances of being scared. Clowes, Lazarus and Ratele (2010) also point to the numerous newspaper reports on gender-based violence while The Shadow Report (2010) presents South Africa as having the highest rate of violence against women, with 40% of cases committed against children (UNICEF, 2009). Violence in South African society is linked to the HIV pandemic with girls and women between the ages of 15-24 years making up 90% of all new infections (UNAIDS, 2008). Even though a drop of 15% in new HIV infections has been reported (UNAIDS, 2011) the successes have largely been measured in terms of biomedical advances, neglecting the social realities of HIV (Singh & Walsh, 2012). If social and structural barriers remain unchanged, the idea of curbing the spread of HIV and achieving 'zero infection' will remain unattainable (NSP, 2011). Reports have indicated the importance of eradicating gender-based violence as a necessity to prevent HIV infection (UNAIDS, 2011; WHO, 2011; NSP, 2011). Unless the reality that one in three women in South Africa is subjected to one or more forms of gender-based violence changes (Jansen van Rensburg, 2007), halting the spread of HIV will not be possible. Ensuring that schools are safe spaces could not only halt gender-based violence but could plausibly also contribute to halting the spread of the epidemic, making this an entry point into addressing the AIDS pandemic.

In this article we first explain the concept of gender-based violence, then go on to briefly highlight theory of power which informs the work and is used to interpret the findings. We discuss the use of participatory video which we frame as a 'research as intervention' approach, present the findings and our discussion thereof, and finally draw some conclusions about gender-based violence in schools and the use of the participatory video as method.

Gender-based violence and power

The construction of 'gender' has implications for understanding gender-based violence. 'Gender' refers to the differentiation between masculine and feminine roles, behaviours, and activities, which is socially constructed. Stereotypes of masculinity and femininity in a patriarchal society pave the way for power inequalities, for example gender-based violence could be a means of disciplining women and girls, keeping them disadvantaged and socially disempowered (WHO, 2005).

Gender-based violence, according to Amnesty International (2012), could be enacted as family violence, for example, marital rape; community violence, for example, human trafficking and stranger rape; and state violence, for example, rape committed by the police, prison guards, and border officials. In this article the focus is on gender-based violence pertaining to youth. Wilson (2012) describes gender-based violence to which youth are most prone to, as two overlapping categories. The first is sexual violence including harassment, intimidation, abuse, assault, and rape. The second category is implicit gender violence which can include corporal punishment, bullying, verbal and psychological abuse, and any form of aggressive behaviour that is violent. For the purposes of this article we draw on Wilson's explanation of gender-based violence.

School is more often than not a reflection of behavioural patterns in society, where males wield power and women and girls do not have much power. Ironically, school, which should serve as a protective factor for youth, often promotes harmful patriarchal, stereotypical masculine and feminine behaviour which may encourage high risk sexual behaviour. This makes girls in particular vulnerable to aggressive sexual advances from male adolescents and teachers (Leach, 2002). According to studies done in 10 southern African countries (WHO, 2005), girls in school often experience a great deal of suffering due to gender-based violence, such as intimidation, harassment and rape, and bear this in silence without reporting or disclosing the abuse (Leach, 2002; Wilson, 2012). Fear, stigma, the unfriendly legal system, and a lack of bringing the perpetrators to book, contribute to the silence. Furthermore, if education officials do not robustly address gender-based violence in the school system, there is the possibility that young people might internalise gender-based violence as normal and legitimate.

This legitimisation of gender-based violence is embedded in power. Power relations are dependent on culture, place, and time (Foucault, as cited by Sadan, 2004:52) and the activation of a social body in which it operates. For Foucault, power "not only operates in specific spheres of social life, but occurs in everyday life. Power occurs at sites of all kinds and sizes, including the most minute and most intimate, such as the human body." (Foucault, as cited by Sadan, 2004:57). Bourdieu (1989) again refers to symbolic power as that which favours certain groups in a community. Overt control and lack of power can influence a person and make him or her do things against his or her true values. This clearly has harmful implications for those positioned with and without power, particularly in relation to gender (Bourdieu, 1989). Those without power in patriarchal societies are most often women and girls. Resisting power inequalities is however not an easy task as structural imbalances act as barriers for taking up own agency (Sadan, 2004). Yet, resistance to power

...is part of the power relations, and hence it is at the same time rich in chances and without a chance. On the one hand, any resistance to existing power relations confirms this power network, and reaffirms its boundaries. On the other hand, the very appearance of a new factor in the power relations - resistance - brings about a redefinition of and a change in the power relations (Wickham, 1986, cited in Sadan, 2004:60).

We use the framework of power in light of raising critical consciousness (Foucault 1980; Freire, 1971; Sadan, 2004) to make meaning ofyouths' experiences and understanding of gender-based violence and their resistance to it, to essentially help them deconstruct harmful social phenomena produced by oppressive powers which lead to social inequalities that are maintained and reproduced through social structures (Foucault, 1980). Considering that school operates within existing social structures, youth too are vulnerable to power inequalities but at the same time able to show resistance to it. This article therefore explores learners' understanding of gender-based violence in school as well as what youth participants envisage doing to resist and make school a safe space, taking up positions as agents of change (Geldenhuys, 2011).

Research questions

Against this background, the following research questions were formulated:

What are Grade 9 learners' understanding of gender-based violence at school?

What solutions do they envisage in addressing gender-based violence in school in order to make it safe?

Research design and methodology

This qualitative study draws on the lived experiences of the youth (Clarke, 2000) to explore how they understand gender-based violence. The study also draws on "critical educational research" (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2007: 26), since working with the participants could contribute to their changing their lived worlds and society in small ways, to reduce "entrapment, domination or dependence within society" and to "contribute to autonomy and freedom" (Cohen et al., 2007: 26). Within the broad frame of participatory research we used participatory video as a data generation tool to engage the participants in constructing their own videos with very little assistance from the research team (Mitchell & De Lange, 2011). This is different from collaborative video, for example, where the researcher works with the participants to create a video production (Banks 2001; Pink, 2001).

We chose to use participatory video with the participants to stimulate discussion around gender-based violence and HIV and AIDS, because of its relevance, as pointed out by Mitchell (2008), particularly in addressing sensitive issues such as gender-based violence and HIV and AIDS. Ultimately, in using visual participatory methods the research becomes an intervention in itself, creating a context for reflection, action, and social change (De Lange & Stuart, 2008; Leach & Mitchell, 2006; Wright, 2011). Stanczak (2007) concurs that participatory video enables voicing of participants' experiences in a new dimension which includes texture, sound, colour, and movement. Such video-enhanced engagement is seen as a powerful tool for stimulating learners' understanding of issues such as gender-based violence which make schools unsafe and them vulnerable in the age of AIDS. It is also useful in involving them in generating their own solutions (Walker, 2004) to address gender-based violence. This blurring of boundaries between research and intervention (Wright, 2011) allows not only for a holistic, critical, and reflective understanding of the participants' lived experiences of gender-based violence in their particular community, but also opens up the possibility for action and social change (Shratz & Walker, 1995).

The context and the participants

The study took place in Vulindlela, a district in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Vulindlela depicts the feminisation of HIV; data from the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA) indicates that "among school children in Grades 9 and 10 in Vulindlela, KwaZulu-Natal, prevalence rates among girls aged 17-18 is 7.9% compared to 1.2% among boys of the same age group" (NPS, 2011:22). Gender-based violence also emerged as a key concern in a previous study involving teachers, community health workers, parents, and learners from the community, in which the learners indicated that gender-based violence was the most pressing issue in their lives (Mitchell & De Lange, 2011).

Two senior secondary schools were conveniently selected as they have been participating in various NRF-funded research projects since 2004, introducing various groups of teachers and learners to the uses of visual participatory methodologies in addressing gender-based violence and HIV and AIDS (Mitchell, De Lange, Moletsane, Stuart & Buthelezi, 2005; Buthelezi, Mitchell, Moletsane, De Lange, Taylor & Stuart, 2007; Moletsane, De Lange, Mitchell, Stuart, Buthelezi & Taylor, 2007; De Lange, 2008; De Lange, Mitchell & Bhana, 2012). The secondary schools are co-educational; one has about 400 learners while the other has more than 1,000 learners. The learners are all isiZulu-speaking and the medium of instruction is English.

Purposive sampling (Silverman, 2000) was used to select participants from Grade 9 and who were thought to be able to express their ideas clearly, and also to provide rich data around gender-based violence. We relied on the educators' judgement for the selection. Thirty learners, 7 boys and 23 girls between the ages of 13-16 years, were chosen. At school A the group was made of 3 boys and 12 girls and at school B 4 boys and 11 girls. At each school we therefore had three groups of 5 learners each, mixing the boys and the girls. We worked with the learners at their schools on Saturdays.

Ethical considerations

We considered ethical issues at two levels. At the level of the university research ethics committee, we obtained the necessary ethical clearance. The Department of Education gave us permission to work in the two schools. The principals of the two schools were very accommodating, thought the research worthwhile, and also granted us permission. Participation was voluntary and written consent was obtained from both the participants and their parents (Trochim, 2006). Anonymity and confidentiality posed challenges as visual data can hardly be anonymous. However, no names of the schools or the participants were revealed.

At a second level, addressing the ethical issues also caused us to think about the ways in which researchers may need to challenge conventional practices related to visual ethics. Central to our research is the notion of doing least harm and most good (Mitchell, 2011; Moletsane, Mitchell, Smith & Chisholm, 2008), and considering the need to - through participatory visual research - make the voices of marginalised, side-lined or silenced groups heard. Caroline Wang's (1999) use of photovoice with women farm labourers in China which made their voices heard and their working conditions seen, enabled policy makers to change policy and improve the women's working conditions, pointing to the power of the visual and its potential for doing 'most good'. As visual researchers we need to challenge the idea of keeping marginalised people 'invisible' and their faces out of visual research. How can the visual data generated by people themselves be used to do 'most good'? How can the visual be used in the community and by the community? How can the visual be utilised to take action and bring about change? And who owns the data? Clearly, these are some of the issues which should be raised when considering visual ethics.

Data production

Using participatory video, the data were produced in four stages beginning with brainstorming, storyboarding, filming, and viewing and discussing the videos. In the participatory video research the process of engaging with pertinent issues is more important than the end product, i.e. the videos.

Brainstorming

After an ice-breaker activity we shared some HIV and AIDS information with the learners and responded to the questions they had, trying to keep the discussion free and easy. We then asked them to brainstorm issues that affect their safety at school, by providing an open-ended prompt, "What affects your safety at school?" They worked in groups, recorded their answers on a sheet of paper and then shared it with the whole group. From their lists, which included issues such as alcohol and drugs, bullying and name calling, fighting, breaking and entry into the school grounds, stealing, using vulgar language, jealousy within relationships, sexual harassment, fear of contracting HIV and AIDS, sex in school with no available condoms, and walking alone to and from school, it became clear that issues around gender-based violence was part of their daily school experiences. This then opened up the opportunity to follow up with a further prompt: "What gender-based violence do you experience in and around school?" They were asked to generate as many examples as possible and to jot them down. We wanted them to be able to indicate which experience was the most pressing, and therefore asked each one to stick a self-adhesive dot next to the issue they personally thought most pressing (See Figure 1).

Once the group had decided which example of gender-based violence was the most pressing, by counting the adhesive dots, we prompted the participants to generate solutions to address this example. The participants again voted on the 'best' solution, and facilitated by the researchers, discussed whether the topic could be represented visually.

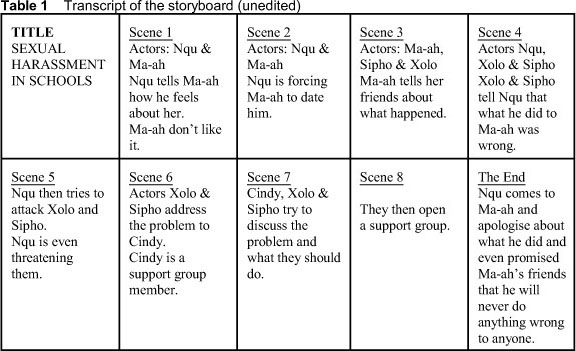

Storyboarding

A storyboard was then created to facilitate planning a video which presents the most pressing issue (which they had identified) as well as a solution. This involved the groups discussing the storyline, briefly outlining the contents of each scene, where to film, who would play which part, and what would be said. Similar to the film industry, we used a storyboard to help draw out their ideas into a script. Participants could choose any genre, but most chose to do a "skit" or (a short drama). Each storyboard had roughly 10-12 scenes (See Figure 2) and included the title and credits. It was exciting for the participants to decide on the 'who, what, where and how' of their video. All participants were required to try out different roles, i.e. being an actor, the director, or the camera person. The resulting six storyboards were then ready to be filmed.

Filming

A hands-on training session and demonstration on how to use the video camera included skills necessary to shoot their videos. The demonstration and practice were around the following: positioning the camera on the tripod, switching the video camera on/off, recording/pausing; panning, framing the shot, good and bad shots, zooming in and out, techniques to record the full script by waiting a second or two before pausing, and rewind/playback. All of the training was geared towards using a "no editing required" approach developed by Mitchell and Mak1 in making participatory videos. This meant that at the end of each scene, the video camera was paused, and when the group was ready to record the next scene, they simply had to push the record button again. If they made a mistake they had to start filming from the first scene again (De Lange & Stuart, 2008). A key point in the video production meant everyone had to be involved in the process of using the camera or acting, and participants had to take turns in doing so.

Viewing and discussion of the videos

Once all the videos had been filmed, the participants were gathered together to watch the videos - shown by connecting the video camera to the data projector - on a portable screen. This was done so that everyone could "see for themselves" (De Lange & Stuart, 2008:19) what other groups had videotaped and so that further discussion could take place around these issues. Viewing the videos allowed us to prompt further reflection, discussion, and feedback, emphasising the agency of the participants.

Data analysis

The data analysed in this article are derived from the brainstorming, storyboards, and video texts. The participatory videos were analysed drawing on Fiske's (1987) work. The six videos were transcribed and the verbatim transcriptions made up the primary text. This article does not include the analysis of the secondary text, i.e. the audience response to the video, or the production text, i.e. the video-makers' comments about their productions (Fiske, 1987). The transcriptions of the participatory video were scrutinised and units of meaning were identified. The units of meaning were combined into meaningful groups (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Tesch, 1990) and organised into categories, which provided the foundation on which interpretations and explanations were based. We reflected on the participants' understandings and allowed themes to emerge. The findings were recontextualised in the existing and published literature of other researchers (Poggenpoel, 1998).

Trustworthiness

Lincoln and Guba (1985) refer to the trustworthiness of findings in qualitative research as findings which can be trusted and are worth paying attention to. We draw on the explanation in De Vos (2005:346) of the "four ... constructs" to explain how credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability were applied. We ensured that the research was credible by carefully considering the context, the selected participants and the theoretical framework to inform the study, which we then clearly described. We also wrote about the research process, providing a thick description (Henning, Van Rensburg & Smit, 2004), and clearly set the theoretical parameters, enabling other researchers to determine whether the research is transferable to different settings. Our research questions served as a strict code of adherence, making the findings dependent on answering these. Both authors were engaged in the data production and cross-checking the participatory videos and transcriptions for accuracy, as well as in the data analysis. Dependability was ensured by clearly explaining the research process and having both researchers analyse the data, followed with a consensus discussion to ensure agreement on the themes. In terms of conformability, we acknowledged our biases in the study, and constantly checked with one another whether we were allowing the voice of participants to be heard (William, 2006).

Findings

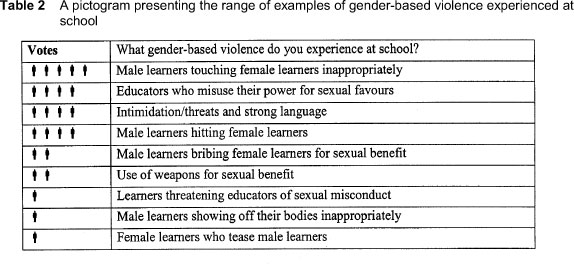

The findings of the different phases of data generation are presented here. Brainstorming Analysis of the brainstorming on what gender-based violence the participants' experienced was done, and the results presented in Table 2 provide a graphic overview of the kinds of issues they raised. Thirty-five topics were listed which, when coded, produced 9 categories. These categories show a range of examples of gender-based violence against both boys and girls, implicating educators and peers.

Storyboarding

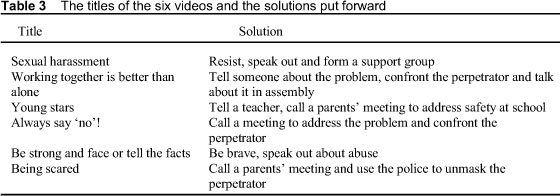

The stories and the solutions offered focus on the idea that gender-based violence is everybody's concern and that broader involvement to address it is required. The solutions however also clearly point to the role of the individual. A summary of the titles of the six videos and the envisaged solutions are presented in Table 3.

Videos as primary texts

The participants produced six videos, each focusing on a particular aspect of gender-based violence with an accompanying powerful message. The titles of the videos sometimes highlight the example of gender-based violence, the emotion felt, or the solution, e.g. "Sexual harassment", "Working together is better than alone", "Young stars", "Always say 'No'", "Be strong and face or tell the facts" and "Being scared". We provide a short description of two videos as examples of what the participants generated. While this does not do justice to the visual text, it does provide a sense of the participatory video work. The two videos point to sexual violence at the hands of a school boy and a teacher.

In "Be strong and face or tell the facts", an upbeat rap to the lyrics of an AIDS song is used. The rap ends with "We are all just the same," linking it to the theme of their video, i.e. the unequal treatment of girls by boys who abuse their power and strength. The video moves from rap song to a short drama showing violent sexual harassment, back to a rap, and concludes with a plea to the audience to stop abuse. In this video the harassment is scaled up to physical violence as in the first scene the boy approaches the girl, and reminds her that they have been dating for two months and still haven't had sex. When she quite strongly states that she is not ready for sex, he forces her to have sex with him. The perpetrator's friend joins in the harassment, highlighting the influence of peers. The video demonstrates the reality of intimate partner violence. The rap rhythm ends with: "Let's be strong and say the facts." The narrator persuades the audience with a clear message that abuse hurts and exacerbates feelings of insecurity and fear (Van der Westhuizen & Maree, 2009), and should therefore be stopped.

In "Being scared", a male educator who sexually abuses a school girl by taking what he wants despite her resistance, is the perpetrator. This is the only video where the girl victim is hesitant to report the abuse, possibly because it is an educator who did the deed. With the encouragement and support from her friends, she talks about the abuse. Together the girls gather enough 'evidence' in the form of a list of names of the teacher's previous victims and report the educator's misconduct to the police for which he then gets arrested. The victim in this video, supported by her girlfriends, firmly insists on an apology from the teacher. In this way she claims back her power.

Emerging themes around gender-based violence

Girls' bodies as sites for gender-based violence at unsafe school sites

In a study by Fineran and Bennett (1999) nearly 90% of the girls indicated that they experienced sexual harassment from male learners. As seen in all six videos, it would seem as girls, significantly more so than boys, experience gender-based violence (Leach & Mitchell, 2006; Peltzer & Pengpid, 2008) such as low-level harassment from peers, intimate partner violence, and educator sexual misconduct at school. Sexual harassment, the most common example mentioned, occurs mostly in classrooms or in the school grounds (De Wet & Jacobs, 2009).

Clearly, as seen in these videos, and supported by other studies like that of Peltzer and Pengpid (2008), girls' bodies become sites of sexual harassment and abuse. Responses of the victims include helplessness, vulnerability, anger, and shame (Hargovan, 2007). It should be noted that although the perpetration was often represented as low-level harassment, the key factor in determining sexual harassment is how the harassment makes the victim feel (DoE, 2001).

Peer sexual harassment was the common thread throughout the participants' videos. From the videos and literature, victims of peer sexual harassment more often than not know the perpetrator. Friends often exacerbate the issue by justifying and encouraging sexual harassment and rape (Dastile, 2008). Some studies have indicated that up to 20% of participants cited peer pressure as the reason for early sexual activity (Shefer, Strebel & Foster, 2000), which might become the reason for gender-based violence.

Unfortunately, sexual violence brings with it an indirect threat of HIV and AIDS infection. Female learners, as seen in these videos, are unable to negotiate condom use. Biologically too, there is a greater risk of HIV infection due to vaginal trauma from exposure to abuse. Many factors could contribute to why girls' bodies are such targeted sites for gender-based violence. These include the use of alcohol and drugs, poor school performance, being abused as a child, poverty, being in a gang, home environment, and societal influences (Van Jaarsveld, 2008). Erikson's (1959) early theory, still useful today, offers an interesting view on why male adolescents are spurred on to sexually harass girls. He links this to how boys who do not go through all the stages of childhood development stand a chance of developing "developmental compression" (Ilesanmi, Osiki, & Falaye, 2010:158). This, according to Erikson (1968), leads to low-level identity development, which is a basic mistrust of oneself and of the future, and which leads the adolescent to identify with what he is least supposed to be (and do), rather than to struggle with demands he cannot meet. This could also provide insight into why boys engage in peer sexual harassment (Erikson, 1959).

Schools are supposed to be safe and secure spaces advantageous for learning (Van Jaarsveld, 2008). It is therefore disappointing that school has become an unsafe site, where guns, knives, and weapons are increasingly present (Leach & Mitchell, 2006). This is evident in the video, "Be strong and face or tell the facts" and has caused a manifestation of violence not only to solve disputes, but also to coerce girls to have sex (Morrell et al., 2009; Van der Westhuizen & Maree, 2009). Van der Westhuizen and Maree's (2009) study is filled with examples of violent attacks at school, claiming an increase in the use of guns and knives and specifically sexual violence targeting girls. Men often use weapons to display their manhood and to control women. This is particularly true among young men who use it as a means to control, hurt, and force victims to get what they want (Abrahams, Jewkes & Mathews, 2010).

School is thus seen as the place where youths 'act out' socially (V an Jaarsveld, 2008) and where sexual harassment and gender-based violence occur, putting both girls and boys at risk of unprotected sex and HIV infection.

'Keepers of safety' are perpetuating gender-based violence at school

Men and boys are usually socially constructed as the stronger sex who could take care of women and girls, who are often socially constructed as the weaker sex. Gender-based violence at the hands of men and boys seems to be a part of everyday life (V an Jaarsveld, 2008). In their videos and according to the research, girls are more often than not the victims (Fineran & Bennett, 1999). Peer pressure increases the possibility of male learners encouraging each other to commit acts of gender-based violence against female adolescents (V an Jaarsveld, 2008). The participants' videos indicated that some boys believe in 'punishing' girls for not wanting to be their girlfriends or not responding positively to their sexual advances (Shefer et al., 2000). Due to peer pressure boys might also feel the need to prove their manhood and power to their friends by wooing many girls, and having more than one girlfriend at a time. Furthermore, if they have money to buy little gifts, alcohol, and drugs for the girls, their power with the girls seems to be increased (Joubert-Wallis & Fourie, 2009). Girls are thus more vulnerable to gender-based violence and ultimately HIV and AIDS (Leach & Mitchell, 2006). Exacerbating the situation is male patriarchy which often causes a culture of silence and acceptance from victims (De Wet & Palm-Forster, 2008) allowing perpetrators even more power. According to Brookes and Higson-Smith (2004) learners keep quiet because they fear repercussions at school or in the wider community. It is the silence that feeds male power and creates a climate for gender-based violence.

Educators, too, do not always protect girl adolescents, but exacerbate the perpetuation of gender-based violence in school. The participants' videos clearly indicated the following realities regarding educators and gender-based violence: male educators commit acts of gender-based violence against girls, and female educators are reluctant to assist victims of gender-based violence and deliberately decide not take action, for various reasons, when gender-based violence is reported. They possibly fear reprisal from adolescent males, like gang vengeance, and therefore avoid conflict at all costs (V an der Westhuizen & Maree, 2009).

Victims and perpetrators are often in relationships indicating intimate partner violence which manifests as physical, psychological/emotional and sexual abuse. Girls, in the study of Shefer et al. (2000), indicated that they did not think rape could happen in a relationship. Such misconception exacerbates the problem and prevents the violence from being spoken about and addressed (Shefer et al., 2000). Male partner violence seems to be accepted rather than viewed as a problem, especially when the victim is in 'love' and unwilling to challenge male power (Shefer et al., 2000).

Culture plays a pivotal role as it often subscribes to male power, making it very difficult for men to resist the socially scripted roles, given the importance of culture in everyday life (Shefer et al., 2000). The powerful male epitomises patriarchy, positioning the male in total control and women their possessions (Leach & Mitchell, 2006; Morrell et al., 2009). As such, an issue like negotiating condom use will be impossible. Culture, patriarchy, and unequal power dynamics are the most common explanations for school-based gender violence.

Learners have a sound understanding of what can be done to address gender-based violence

Participants in this study had a sound understanding of how to address gender-based violence in school. In the six videos the participants did not buy into disempowerment, nor did helplessness overshadow their sense of agency as they resisted the gender-based violence prevalent in school; they showed a clear sense of agency.

The participants themselves showed a willingness to resist gender-based violence by saying 'no', reporting abuse, and speaking out about the problem. They indicated that although they were protected by fences, cameras, and security staff at school, school safety is a collaborative project. This for example includes the disrupting of stereotypical boy and girl behaviour and changing the unequal power dynamics seen in the home, school, and community. It is also seen in formal structures such as the police, where reporting gender-based violence is a further trauma.

In the six videos participants thus gave a voice to possible ways of addressing 'a silent problem'. The key is to tell someone about the violence, breaking the silence, and being proactive (De Wet & Palm-Forster, 2008; Prinsloo, 2006). This they demonstrated through reporting the gender-based violence, addressing the problem in school assembly, and forming support groups, all of which were aimed at taking action. Even though speaking out against gender-based violence is a complex matter, they simulated clear actions of reporting crimes and showing bravery without fear of reprisal from perpetrators (Rape Survivor Journey, 2010).

Peer support, evident in most of the videos, was presented as critical in addressing gender-based violence at school. The peer assistance showed that the participants understood that communication is important - making clear what is felt, what is needed, and how to equalise power differentials. Establishing gender equity lies in everyone's willingness to assist, similar to the traditional belief of Ubuntu, 'I am because we are.' This attitude builds social capital and a whole community that is gender-sensitive and inclusive (Moletsane, Mitchell, De Lange, Stuart, Buthelezi, & Taylor, 2009).

Limitations and delimitations

This study focused on how a small group of secondary school learners from a rural context understand gender-based violence in their school and what solutions they can generate to curb gender-based violence and therefore indirectly contribute to halting the spread of HIV and AIDS. The use of participatory video was particularly important in encouraging deep engagement in a real problem and getting the participants to think about school safety. While the enthusiasm of the participants was clearly visible in working with participatory video, and while we noted their sense of agency and the possibility for social change, we are also aware that while we, along with other researchers, are "pushing ... methodological boundaries" (Mitchell, Milne & De Lange, 2012: 2) we should not be uncritical in the use of participatory video.

This qualitative study has its limitations; the small number of participants limits the generalisability of the findings. A thorough description of the research process and the context could however enable other researchers to transfer the findings to similar rural settings because the study does provide some insight into how rural youth understand their own lived contexts and how they position themselves as able to take up their own agency and making their voices heard. A further limitation is the use of language. Although the learners were allowed to use their mother tongue (isiZulu) in the videos, they opted to use English, which could possibly have had an effect on how they expressed their ideas. A further limitation is that the number of girls outweighed the number of boys which could bias the data, favouring the voices of the girls.

Conclusion

At the beginning of the article we positioned gender-based violence as a driver of the HIV and AIDS epidemic, and it was from these a priori assumptions that we explored learners' understanding of gender-based violence and what solutions they envisaged to address gender-based violence in their schools. When we worked with the learners we contextualised the participatory video work we wanted to do within the realities of HIV and AIDS in their community. The implication was that if learners were more vigilant and conscious of gender-based violence and its link to HIV, they would also be more aware of how to keep themselves safe as well as make schools safe.

The findings mostly concur with the literature, indicating that schools are still unsafe spaces, with girls and women bearing the brunt of the violence often at the hands of men and boys. A particular contribution offered is towards understanding gender-based violence through the eyes of a small group of rural youth. It also offers insight into how some rural school children position themselves as agents of change, by thinking how they might take action towards safeguarding themselves, and by drawing on the assistance of others. While this study has not made the schools safe, from a 'research as intervention' perspective, it has enabled the participants to reflect on their own agency in resisting gender-based violence.

Looking at the findings through the lens of power, we see how participating learners understood and constructed gender-based violence within existing power relations of a traditional and patriarchal society, and also how they in small but powerful ways challenged the power in spite of structural imbalances, by resisting being victims. Wickham's (1986, cited in Sadan, 2004:60) notion that "resistance is part of ... power relations" is pertinent. Through their resistance - demonstrated in their solutions presented in the participatory videos - the learners actually confirmed the existence of the power network in the community and school, where men and boys still hold most power, and where women and girls are afraid of speaking out, reaffirming the power boundaries set for men and boys and women and girls. At the same time the resistance of the learners brought about a redefinition of power relations in small ways, by working through how they might take action and take up agency.

This is where the strength of the methodology lies; in contributing to youth taking action in making schools safe. The study focused on understanding and addressing gender-based violence through the use of participatory methodologies, in particular participatory video. The latter not only enabled data generation but also created a space for the participants to discuss real and relevant problems and, more importantly, enabled them to consider how to resist in constructive ways. The voices of the youth contribute to helping school and community to better understand the nature of gender-based violence in school and more importantly, how to make positive changes in their own lives and those of others. The methodology contributed to a 'mental awakening' in the participants, leaving them with richer insights and ways of how to make positive contributions to their own well-being (Swart & Bredekamp, 2009). This mental awakening was present when one of the participants concluded:

"The message that we are trying to express is a message of... of expressing ourselves as girls. Boys force girls to have sex with them and threaten them with weapons. So us, we wanted to give a message that we must tell the facts and say we don't like that thing and that is it." Girl participant, School B

To make school a safe place therefore requires a comprehensive plan, involving the whole community, i.e. the learners, the parents, the teachers, the School Management Team, the School Governing Body, the DoE district officials (V an Jaarsveld, 2008), the police, and the induna who presides over the community. This might include having a "safe school programme", creating appropriate school policies, specifically a sexual harassment policy, and safety and security measures to protect and keep all learners, but more specifically girls, safe. These could be generated from grassroots level and not imposed on the school and community. We believe that participatory video can be used to contribute to change from grassroots up.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the funding and support of the National Research Foundation (NRF). We thank Claudia Mitchell for her critical comments towards refining the article.

Note

1 We acknowledge Claudia Mitchell and Monica Mak (a filmmaker at McGill University) for coining the term No-Editing-Required (NER).

References

Abrahams N, Jewkes R & Mathews S 2010. Guns and gender-based violence in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 100:586-588. [ Links ]

Amnesty International 2012. Violence against women. Available at http://www.amnestyusa.org. Accessed 25 May, 2012. [ Links ]

Banks M 2001. Visual methods in social research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Barnes K, Brynard S & De Wet C 2012. The influence of school culture and school climate on violence in schools of the Eastern Cape Province. South African Journal of Education, 32:69-82. [ Links ]

Bourdieu P 1989. Social space and symbolic power. Sociological Theory, 7:14-25. [ Links ]

Brookes H & Higson-Smith C 2004. Fundamentals of social statistics: an African perspective. Landsdowne: Juta. [ Links ]

Buthelezi T, Mitchell C, Moletsane R, De Lange N, Taylor M & Stuart J 2007. Youth voices about sex and AIDS: implications for life skills education through the 'Learning Together' project in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11:445-459 [ Links ]

Clarke P 2000. Internet as a medium for qualitative research. South African Journal of Information Management, 1-18. [ Links ]

Clowes L, Lazarus S & Ratele K 2010. Risk and protective factors to male interpersonal violence: views of some male university students. African Safety Promotion, 8:1-19. [ Links ]

Cohen L, Manion L & Morrison K 2007. Research methods in education. (6th ed.). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Dastile NPl 2008. Sexual victimisation of female students at a South African tertiary institution: the victim's perception of the perpetrator. Acta Criminologica: CRIMSA Conference Special Edition, 2:189-206. [ Links ]

De Lange N 2008. Women and community-based video: Communication in the age of AIDS. Agenda, 77:19-31. [ Links ]

De Lange N, Mitchell C & Bhana D 2012. Voices of women teachers about gender inequalities and gender-based violence in rural South Africa. Gender and Education, 24:499-514. [ Links ]

De Lange N & Stuart J 2008. Innovative teaching strategies for HIV & AIDS prevention and education. In L. Wood (Ed.) Dealing with HIV/AIDS in the classroom. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

De Vos AS 2005. Qualitative data analysis and interpretation. In De Vos AS, Strydom H, Fouche CB & Delport CSL (Eds). Research at grass roots, for the social sciences and human service professions. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

De Wet C & Jacobs L 2009. Comparison between boys' and girls' experiences of peer sexual harassment. Journal for Christian scholarship, 45:55-75. [ Links ]

De Wet C & Palm-Forster T 2008. The voices of victims of sexual harassment. Education as Change, 12:109-131. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2001. Opening our Eyes: Addressing Gender-Based Violence in South African Schools. Available at http://www.cvm.ukzn,ac.za. Accessed 3 September 2009. [ Links ]

Erikson EH 1959. Identity and the life cycle. Selected papers, 1:1-171. [ Links ]

Erikson EH 1968. Identity, youth and crisis. London: Faber & Faber. [ Links ]

Fineran S & Bennett L 1999. Gender and power issues of peer sexual harassment among teenagers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14:624-641. [ Links ]

Fiske J (Ed.) 1987. British cultural studies television. London: Methuen. [ Links ]

Foucault M 1980. Power/knowledge: selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. New York: Pantheon. [ Links ]

Freire P 1971. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Seabury. [ Links ]

Geldenhuys, M. 2011. Gender-based violence in the age of AIDS: Senior secondary school learners' envisaged solutions in two rural schools in KwaZulu-Natal. Unpublished MEd dissertation. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Hargovan H 2007. Restorative approaches to justice: "compulsory compassion" or victim empowerment? Acta Criminologica, 20:113-123. [ Links ]

Henning E, Van Rensburg W & Smit B 2004. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch 2001. Scared at school: Sexual violence against girls in South African Schools. New York, London, Washington, Brussels: Human Rights Watch. [ Links ]

Ilesanmi OO, Osiki JO & Falaye A 2010. Psychological effects of rural versus urban environment on adolescent's behaviour following pubertal changes. IFE PsychologIA : An international journal, 18:156-175. [ Links ]

Jansen van Rensburg MS 2007. A comprehensive programme addressing HIV/AIDS and gender based violence. SAHARA: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance, 4:695-706. [ Links ]

Joubert-Wallis M & Fourie E 2009. Culture and the spread of HIV. New Voices in Psychology, 5:105-125. [ Links ]

Leach F 2002. School-based gender violence in Africa: A risk to adolescent sexual health. Perspectives in Education, 20:99-112. [ Links ]

Leach F & Mitchell C (Eds) 2006. Combating gender violence in and around schools. London: Trentham books. [ Links ]

Lincoln YS & Guba EG 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage. [ Links ]

Miles MB & Huberman AM 1994. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Mitchell C 2008. Getting the picture and changing the picture: Visual methodologies and educational research in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 28:365-383. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C. (2011). Doing visual research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Mitchell C & De Lange N 2011. Community-based participatory video and social action in rural South Africa. In E Margolis & L Pauwels (eds). The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, De Lange N, Moletsane R, Stuart J & Buthelezi T 2005. Giving a face to HIV and AIDS: On the uses of photo-voice by teachers and community health care workers working with youth in rural South Africa. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2:257-270. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, Milne E-J & De Lange N 2012. Introduction. In E-J Milne, C Mitchell & N de Lange. The handbook of participatory video. Plymouth, UK: Alta Mira Press. [ Links ]

Moletsane R, De Lange N, Mitchell C, Stuart J, Buthelezi T & Taylor M 2007. Photo Voice as an Analytical and Activist Tool in the Fight Against HIV and AIDS Stigma in a Rural KwaZulu-Natal School. South African Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 19:19-28. [ Links ]

Moletsane R, Mitchell C, Smith A & Chisholm L 2008. Methodologies for mapping a Southern African girlhood. Rotterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Moletsane R, Mitchell C, De Lange N, Stuart J, Buthelezi T & Taylor M 2009. What can a woman do with a camera? Turning the female gaze on poverty and HIV and AIDS in rural South Africa. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22:316-331. [ Links ]

Morrell R, Epstein D, Unterhalter E, Bhana D & Moletsane R 2009. Towards gender equality South African schools during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

National Strategic Plan for HIV and AIDS, STIs and TB, 2012-2016 2011. Available at http://www.gov.ac.za. Accessed 31 May 2012. [ Links ]

Peltzer K & Pengpid S 2008. Sexual abuse, violence and HIV risk among adolescents in South Africa. Gender and Behaviour, 6:1462-1478. [ Links ]

Pink S 2001. Doing visual ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Poggenpoel M 1998. Data analysis in qualitative research. In De Vos AS, Strydom H, Fouche CB & Delport CSL. (Eds). Research at grass roots (4th ed.). Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, S 2006. Sexual harassment and violence in South African schools. South African Journal of Education, 26:305-318. [ Links ]

Rape Survivor Journey 2010. Rape Statistics - South Africa & worldwide. Available at http://www.rape.co.za/index2.php?option=com_content&do_pdf=1&id=875. Accessed 8 June 2010. [ Links ].

Sadan E 2004. Empowerment and community planning: Theory and Practice of People-Focused Social Solutions. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishers E-book (English translation, 2004), Available at http://www.mpow.org/elisheva_sadan_empowerment_intro.pdf. Accessed 18 October, 2012. [ Links ]

Silverman D 2000. Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Sage Shadow Report 2010. Criminal injustices violence against women in South Africa. Beijing. Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cedaw/docs/ngos/POWA_Others_SouthAfrica48.pdf. Accessed 1 December 2010. [ Links ]

Shefer T, Strebel A & Foster D 2000. "So women have to submit to that ..." Discourses of power and violence in student's talk on heterosexual negotiation. South African Journal of Psychology, 30:11-19. [ Links ]

Schratz M & Walker R 1995. Research as social change: New opportunities for qualitative research. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Singh G & Walsh CS 2012. Prevention is a solution: Building the HIVe. Digital Culture & Education, 4:5-17. [ Links ]

Stanczak G 2007. Visual research methods: image, society, and representation. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Swart E & Bredekamp J 2009. Non-physical bullying: exploring the perspectives of grade 5 girls. South African Journal of Education, 29:405-425. [ Links ]

Tesch R 1990. Qualitative research: analysis types and software tools. London: Falmer. [ Links ]

Trochim W 2006. Ethics in Research. Available at http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/ethics.php. Accessed 19 July 2008. [ Links ]

UNAIDS 2008. AIDS. Available at http://www.unaids.org. Accessed 21 June 2008. [ Links ]

UNAIDS 2011. How to get to zero. Faster. Better. Smarter. Available at www.safaids.net/files/wordlAIDSday_report_2011. Accessed 25 May 2012. [ Links ]

UNICEF 2009. Women and children in South Africa. Available at http://www.unicef.org/southafrica/children.html. Accessed 25 January 2010. [ Links ]

Van der Westhuizen CN & Maree JG 2009. The scope of violence in a number of Gauteng Schools. Acta Criminologica, 22:43-62. [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld L 2008. Violence in schools: a security problem? Acta Criminologica: CRIMSA Conference, Special Edition, 2:175-188. [ Links ]

Walker S 2004. An innovative, participatory visual methodology for stimulating intergenerational communication and strengthening community support for HIV/AIDS prevention with young people: a Ugandan case study. Available at http://www.nmlgateway.org. Accessed 19 July 2008 [ Links ]

Wang C 1999. Photovoice. A participatory action research strategy applied to women's health. Journal of Women's Health, 8:185-192. [ Links ]

William MK 2006. Research method knowledge Base. Accessed 6 October 2010. Available at http://www.socialresearchmethods.net. [ Links ]

Wilson F 2012. Gender Based Violence in South African Schools. Available at hrtp://www.iiep.unesco.org/fileadmin/user.../research...and.../WilsonF. Accessed 11 August 2012. [ Links ]

World Health Organisation 2005. Violence against women and HIV/AIDS : critical intersections - intimate partner violence and HIV/AIDS. Accessed 22 June 2010. Available at www.who.int/. [ Links ]

World Health Organisation 2011. Global HIV/AIDS response. Available at http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progree_report2011. Accessed 25 May 2012. [ Links ]

Wright M 2011 Research as intervention: Engaging silenced voices. Action Learning Action Research Journal, 17:25-46. [ Links ]