Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.32 n.4 Pretoria Jan. 2012

The use of drawings to facilitate interviews with orphaned children in Mpumalanga province, South Africa

Teresa A Ogina

Department of Education Management and Policy Studies, University of Pretoria, South Africa Teresa.Ogina@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

HIV/AIDS and being orphaned impact greatly on children's lives. This article explores the life experiences of orphaned children in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. In this qualitative case study, draw-write techniques andface-to-face interviews were used to generate data related to the experiences of the children. Results suggest that although the interviewed children yearn for their parents and experience unmet emotional and material needs, they use promotive factors, such as personal agency and environmental relationships, as resilience in fulfilling their needs. Furthermore, the results suggest relationships based on values, such as caring, respect and mutual understanding, as protective factors that may contribute to the fulfilment of social needs as well as enabling their emotional well-being.

Keywords: draw-write technique, HIV/AIDS, orphaned children, resilience, risk factors, South Africa.

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to explore the lived experiences of orphaned children in order to determine their needs. In this study an orphan is a child of under 18 who has lost one or both parents (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS], United Nations Children's Fund [UNICEF] & United States Agency for International Development [USAID], 2004). Research (Monasch & Boerma, 2004; Cluver & Gardner, 2007; Van Wyk & Lemmer, 2007) has highlighted an increase in the number of children without parents, mostly as a result of HIV/AIDS, addressing a need to understand the world of these children in order to provide the services they need.

Zhang (2007) acknowledges that, generally, parents are expected to provide for their children's physical, social and psychological needs, including their need for love, emotional attachment and a sense of belonging. The findings of studies on parental attachment and school achievement (Holmes, 1993; Ferrara & Ferrara, 2005; Bettmann, 2006) indicate that the care, support and encouragement that children receive from their parents have a positive effect on their behaviour and on their achievements at school. Whilst there are many studies that have documented the experiences of orphaned children in the context of HIV/AIDS (Cluver & Gardner, 2007; Kidman, Petrow & Heymann, 2007; Chitiyo, Changara & Chitiyo, 2008), this study provides insight into, and adds to knowledge about, the experiences of orphaned children in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. The working assumption is that children without parents are unlikely to have their material, social, and emotional needs fulfilled.

Childhood within an HIV/AIDS context

HIV/AIDS and being orphaned impact greatly on children's lives. It is estimated that in South Africa 13% of orphans between the ages of 2 and 14 have lost one or both parents in AIDS related deaths (Townsend & Dawes, 2007). Some orphaned children are psychologically traumatised by their parents' illnesses and deaths and lack social and emotional support (Giese, Meintjes, Croke & Chamberlain, 2003; Chabilall, 2004; Robson & Kanyanta, 2007; Van Wyk & Lemmer, 2007; Moletsane, 2008). The psychological trauma experienced by the children may manifest itself in the form of depression, sadness, anger or guilt (Mohangi, 2008). In addition, these children may also be ostracised from the community and the school because of the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS (Chitiyo et al., 2008).

Resilience - theoretical framework

Many studies (Cluver & Gardner, 2006; Smit, 2007; Mokoae, Greef, Phetihu, Uys, Naidoo, Kohi, Dlamini, Chirwa & Holzermer, 2008; Kangethe, 2009) explain coping as the need to adapt as a result of stressors in the presence of adversity - indistinguishable from HIV/AIDS-related challenges. Resilience denotes coping (positive adaptation) which is characterised by the ability to overcome the negative effects of considerable adversity (risk exposure) (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005; Luthar, 2003). Thus, resilience represents the speed and effectiveness of a coping repertoire which is common amongst children growing up in disadvantaged conditions (Masten, 2001). Viewed through a positive psychological lens, Masten (2001), Kaplan (2005) and Keyes (2007) acknowledge the role of human strength as a buffer in such adverse circumstances.

Within a resilience framework, orphanhood constitutes adversity while signalling the need to adapt (Mohangi, 2008; Chabilall, 2004). Ebersohn (2007; 2008) argues that orphanhood that results from HIV/AIDS-related deaths implies cumulative risk. Whereas all orphaned children are faced with a myriad of challenges, such as emotional, social and caretaking problems, children orphaned as a result of AIDS also need to cope with the stigma of, and the discrimination, that result from the pandemic. These challenges embody risk that may present barriers to the children's ability to cope. Fredrickson (2001) notes that, theoretically, the adaptation of children orphaned as a result of AIDS can be buoyed by protective factors that include individual characteristics, such as positive emotions, environmental factors and positive relationships that serve as buffers to challenges. One such protective factor which enables adaptive engagement with adversity is a relationship with a significant adult - related specifically to the domain of children's resilience regarding adversity in the context of HIV/AIDS (Ebersohn, 2007). Another protective factor is that of hardiness (Bonanno, 2004) where a meaningful purpose in life and a belief in one's ability to affect the environment is one of multiple pathways to resilience. Furthermore, linked to promotive factors, that enhance the positive psychological well-being of the child, are feeling happy, interested and relaxed against the risk of emotional distress (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). Such positive assets within the child are accompanied by resources, such as parental support, adult mentoring and community organisations (Ebersohn, 2008) to increase resilience and reduce stressors.

Research design and methodology

The research design for this study is a qualitative, interpretive case study involving a primary and a secondary school whose learners include orphaned children. The reason for choosing a case study design was to enable the researcher to interact with the children to explore, in depth, their experiences within a bounded system (Merriam, 1998; Stake, 2000) - in this case, the school. The qualitative data used in this article were collected as part of a larger case study (Ogina, 2008) in a rural area of Mpumalanga province in South Africa.

The study was motivated by the Brink Report (UNAIDS et al., 2004) which estimated the number of orphans in South Africa in 2000 to be 1.8 million and projected a figure of 3.1 million for 2010. The Bradshaw Report (2005), released to the media by Medical Research Council, indicated that Mpumalanga was the province with the second highest number of AIDS deaths (40.7%) after KwaZulu-Natal, which led with 41.5%. The researcher purposely selected the site for the study as the area is characterised by unemployment and single parents, with the majority of children living with their grandparents or other relatives after the demise of their parent/s.

The collected data were obtained from participants' drawings and narrations, followed by individual interviews. The reason for choosing drawing and narration as a data collection technique is that it allows the children to take control of the research process by determining what they want to share with the researcher (Young & Barrett, 2001). It is a bottom-up approach that enhances the children's participation in the research and presents opportunities to explore the meaning of their experiences in order to understand their views (Backett-Milburn & Mc Kie, 1999; Dockrell, Lewis & Lindsay, 2000). Some researchers (Backett-Milburn & McKie, 1999; Yuen, 2004; Driessnack, 2006) consider drawing to be a relaxing exercise whereby an individual's defensiveness is reduced and, as a result, it enhances communication which makes it an appropriate approach in exploring the experiences of orphaned children.

Sample

A snowballing technique was used to identify teachers in the selected schools with a high number of orphans. The teachers became the gatekeepers of the research site and the researcher, with the help of the teachers, used purposive sampling - carried out in two steps - to select participants. In the first step all the orphaned children were invited, on a voluntary basis, to a draw-and-write session. These sessions were conducted in each of the two selected schools. In the first school (primary) 35 children attended the session and in the second school (secondary) 22 attended. The age group of the orphaned children in the primary school ranged from 10 to 16 and in the secondary school from 14 to 17.

Researchers (Creswell, 2002; Denzin & Lincoln, 2000) recommend that before seeking consent from the participants, the researcher should inform them of the nature and the consequences of the research. These orphaned children were initially asked whether they were willing to participate in a draw-and-write session and later they were asked to participate in the interviews. The children were made aware of their right to refuse to participate in the draw-and-write session and in the interview. Although there is a possibility that some of the children participated because of a feeling of obligation to their teachers, the researcher tried to reduce this by talking to the children in the absence of their teachers. They were, then, given two weeks to decide whether or not they wanted to participate in the study.

Data generation

The researcher began by sharing her own life story with the children, using a poster with drawings to depict her and her story. This was deemed necessary to show the children that all people have a story to tell and how they can share their story with others. The researcher used drawings to provide visual images, narration, and an example of how children who are orphan- ed could talk to the researcher about themselves through drawing. During the session the researcher gave the children coloured paper and pencils and told them to tell her a story about themselves by drawing pictures. While they were drawing, the researcher asked them to write about who was in their drawing and what they were doing.

Young and Barrett (2001) maintain that children are capable of expressing themselves freely, and of deciding on what they want to share with researchers through their drawings. The use of coloured paper and pencils was to make the exercise interesting, relaxing and enjoyable. Drawing encourages children to talk about sensitive issues and it stimulates a detailed description of specific emotions and experiences (Yuen, 2004; Driessnack, 2006). The researcher explained to the participants that their role in the research was to tell their stories about their experiences. The researcher then attempted to identify the needs of the learners through their drawing and what they said.

In the second step the researcher purposively approached children who had completed a drawing with a written story about their drawing. There were children who indicated in writing on their drawing that they wanted to talk to somebody about their experiences. It seemed that in talking about their experiences the children would reveal an awareness of their needs and that it would possibly be a form of healing as they had someone they could trust to talk to. Such children were considered as a potentially rich source of data. The researcher again reminded them of their consent before asking them to talk about their drawings, their written narrations and their day-to-day life experiences. The children who did not draw or write a story about their daily lives were not included in the sample on the assumption that they were not willing, or able, to share their experiences with the researcher. The children who consented to be interviewed included five boys and seven girls between the ages of 14 and 17 from a primary and a secondary school. They were deemed to be able and willing to talk about their experiences, based on the information that they had revealed in the drawings and written texts. The children's drawings and narrations were used as an entry point in the interviews, enabling the researcher to ask questions focusing on the issues that mattered most to the participants (Yuen, 2004; Driessnack, 2006).

The researcher used the drawings and the written narration as a way to facilitate the interviews with the children. The interview sessions were conducted after they had drawn their stories as the findings from other studies have suggested that children tend to speak more freely when they are first given the opportunity to draw before a conversation takes place (Driessnack, 2006). This strategy was deemed less threatening than asking the orphaned children direct questions.

The discussion of the drawings was more revealing than the visual presentation itself. This corresponds with the findings of Young and Barrett (2001) in their research of the street children of Kampala - using visual methods, such as photographic diaries, drawings and maps, to elicit information from them about their interaction with their social-spatial environment. The children who participated in Young and Barrett's (2001) study had little or no contact with their parents or guardians, having left home because of ill-treatment, parental death or poverty. The purpose of using visual methods was to encourage child-led activity and to minimise the involvement of the researcher.

In this study the researcher probed the children during the interview to tell her more about their drawings and their written texts. As the orphaned children narrated their experiences, the researcher probed for greater clarity and depth by asking them to elaborate further. The researcher was able to identify some of the needs of the learners as they talked about their experiences. Some of the questions asked were: "What is happening in the drawing?" and "Who is in the drawing and what is s/he doing?" Figure 1 shows a drawing by Thandi (pseudonym) with her narration. An extract from the transcription of the interview with Thandi is also included in the figure.

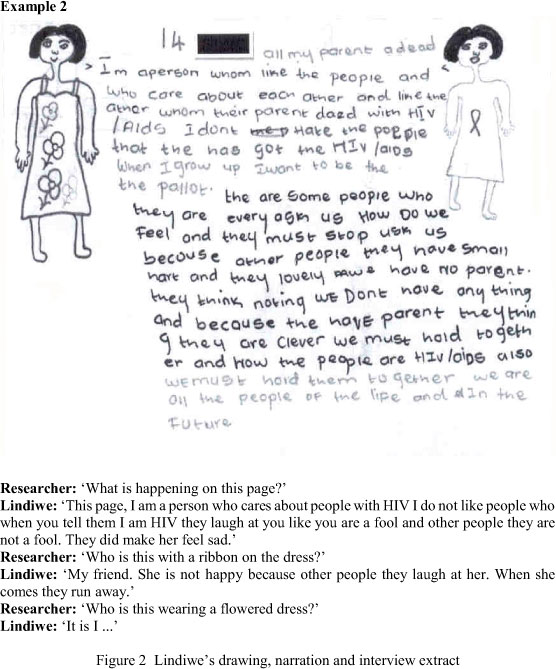

Figure 2 is another example by Lindiwe (pseudonym) who drew two children and wrote about her feeling concerning HIV/AIDS and other people. Dockrell et al. (2000) describe this approach as a way of giving children an opportunity to organise their thoughts and decide what they want to share with the researcher.

The researcher believed that the children's perspectives would provide insights into their experiences of orphanhood and into the needs of orphans.

Data analysis

The data analysis entailed a back-and-forth process of systematic data collection and data analysis and a constant comparative analysis and memo writing, from which the conceptual themes were extracted (Charmaz, 2000). The interview transcripts, the written narrations and the field notes were coded and categorized. The categories were then compared with each other for similarity and the relationship between and within the categories (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The core category and emerging patterns were identified by means of a constant comparative analysis. The meanings of the drawings were determined from the responses of the children to the questions asked about their drawings. This approach enabled the researcher to identify themes in the children's experiences. Trustworthiness was ensured by using an oral data eliciting method - based on the visual information provided by the children and by taking the coded data and emerging themes back to the children to check for accuracy and to elicit further comments. The researcher triangulated data from the drawings, the narrations and the interviews to increase depth and accuracy.

Results

Several themes emerged from the data collected from the orphaned children's drawings, narrations and interviews. The themes include a yearning for parents, financial and material needs, stigma and relationship with others, and future expectations.

Yearning for parents

Most of the orphaned children expressed an emotional longing and grieved for parents who had passed away: ' When I heard that my mother died I cried and asked myself a question why did God take my mother because my mother is the person close to me' (Tshepo). One of the children did not want to talk about her parents, explaining that the memories of her parents made her feel sad. This child's feelings suggest a continued grief and bereavement (Sengendo & Nambi, 1997). Researchers commonly maintain that orphans need emotional support because of their high levels of psychological distress (Atwine, Cantor-Graae & Bajunirwe, 2005; Cluver & Gardner, 2006).

Financial and material needs

Most of the orphans associate the longing for their parents with unmet needs. The children expressed their need for financial and material support in different ways: ' When you stand up they think you cannot afford anything because you do not have a mother and a father and they will have everything because they have a mother and a father' (Lindiwe). Some of the children go to school without breakfast, and also miss out on lunch and dinner: 'I am suffering because sometimes there is no food at home; I come to school without eating anything' (Lebo).

While some orphans feel quite vulnerable in terms of nutrition, others find ways of coping with such adversity. ' When there is no food, I pack my prep book, drink water, relax for fifteen minutes then go back to school' (Tshepo). Some orphans depend on food occasionally supplied by relatives and a government feeding scheme at the school: 'In school they give bread to people who do not have food two times a week' (Zodwa). This finding is in line with the study done by Giese et al. (2003) that reports cases of children being absent from school because of hunger. Similarly, Makame, Ani and Grantham-McGregory (2002) find that children who are orphaned are more likely to lack food than non-orphans.

Some of the relatives supply school uniforms and pay school fees: 'I was given this uniform by my aunt and uncle they also paid my school fees' (Karabo). This illustrates a situation of material vulnerability by pointing to the challenges faced by orphans attending school as well as providing insight into the financial and material support orphans receive from their kin. Foster (2002) suggests that educators identify orphaned children by the non-payment of school fees, lack of food and poor clothes.

In the study, two of the 12 orphans had health conditions that required constant medical care. From their narration it seems that accessing medical care was hindered because there was no one to take the children to the clinic/hospital, and because of a lack of funds for medicine: 'I feel sick, I want to go to the hospital but I do not have money to go to the hospital so I get medicine from my sister's friend' (Mpumi). Apparently Mpumi copes by obtaining medical assistance from her sister's friend who is a nurse. Another orphan says: ' When I use to get flu and stomach ache my mother would take me to the hospital but since she passed way there is nobody to take me to the hospital' (Thandi). These narrations highlight the absence of a care-giving system that enables access to health services.

Stigma and relationships with others

During the interviews the orphaned children spoke about feeling alienated, angry, frustrated and helpless: 'When you are an orphan, they talk about you. When working in groups, they do not want you to be their group' (Lindiwe). 'People hate me for nothing, when I ask them why you hate me they do not answer' (Lerato). These responses suggest a stigma associated with orphanhood which contributes to the alienation and isolation of orphaned children.

Despite the stigma, participants reflected on their relationships with their kin, peers and teachers. There were cases where orphans told of being mistreated by relatives and of being unsupported: 'My grandmother treat me like a dog, she does not care about me' (Lesego). The narration underlines rejection by a caregiver and a feeling of being treated inhumanely.

However, other orphans have supportive relatives: 'I am proud of my grandmother because she tries to do everything for me but she cannot afford to buy me things. I wish that my grandmother could have many things. I love her and she loves me' (Lindiwe).

In one particular child-headed family, consisting of two brothers and a sister, the coping strategy adopted by the siblings was a close supportive relationship: ' We stay nice. We do not bother each other. We stay like brothers. I respect him and he respects me. We do notfight with my sister like others but help each other' (Tshepo). Tshepo's experience of living in a child-headed family is a supportive and harmonious relationship anchored in respect and a family bond. These descriptions of loving and caring relationships suggest the fulfilment of emotional needs. Landry, Luginaah, Maticka-Tyndale and Elkins (2007) maintain that orphans who are treated well by caregivers are better able to cope than those who are not well-treated. Similarly, a study in Tanzania found that sibling relationships - as well as relationships with other surviving household members - could be a source of emotional support and protection that enables resilience in orphaned children (Evans, 2005).

There were narrations by the children who experienced positive and supportive relationships with their peers: 'Here at school I have three friends, I walk with them to school and they also visit me at home' (Tshepo). Tshepo acknowledges the importance of socialisation skills; developing companionship; and a socially supportive relationship with his peers. Karabo described his relationship with his peers as loving and caring: 'I have good friends, they come with break and they call me to come and eat with them'. Such relationships may fulfil the children's physical, social and emotional needs. Similar findings were reported in other studies (Cluver & Gardner, 2007; Atwine et al., 2005) where children felt protected and comfortable in the company of friends.

However, some children experience rejection, alienation and being discriminated against by their peers: ' Where I live my friends told me - you are not my friend, your mother passed away' (Lesego). ' When you stand up when you are an orphan, they have a topic about you' (Lindiwe). Such rejection highlights the consequences of the stigma of orphanhood (Evans, 2005; Cluver & Gardner, 2006).

Relationships between the orphaned children and their teachers were generally positive: 'Teachers are great; they teach and respect us' (Tebogo). 'They treat us like others and help as educator' (Lindiwe). ' I like my educator because they teach me what I do not know' (Lesego). Most of the children view their teachers as respectful, non-discriminatory and supportive. This indicates the central role of teachers as secondary caregivers in providing a positive and supportive relationship with children where parents are absent - echoing related studies with teachers (Ferreira, 2008; Loots & Mnguni, 2008).

Future expectations

The majority of the orphaned children who offered to share their stories had a positive self-image: 'I like myself. I do not say, why God made me liked this' (Lebo). Some of the narrations suggest the future, rather than focusing on painful past experiences: 'f I stress that my mother passed away, I will not be able to move on. Ijust want to forget about it because life goes on' (Tshepo). The future career aspirations of most of the children involve helping people: 'I want to be a social worker to help other orphans have grants and good education' (Nomsa). 'When I finish school I want to be a nurse to help sick people' (Mpumi). Other researchers have described this ability to have positive future aspirations and be optimistic, hopeful and caring of others as indications of resilience (Evans, 2005; Mohangi, 2008).

In some instances orphaned children distract themselves from negative experiences by either mentally re-focusing attention or engaging in an activity: ' When its lunchtime and there is no food to eat, I pack my prep book, drink water, relax for fifteen minutes then go back to school' (Tshepo). During the drawing session one child drew herself and her friend. She wrote that she liked playing with her friend, as she did not, then, think about her parents. These distracting strategies may also signify agency in orphans as they choose not to be present as victims in unfavourable circumstances and use avoidance, fantasy and play as mental resources to focus on positive scenarios (Bonanno, 2004). Playing with friends could be a way children cope with grief; they escape from reality into a space in which they can be active and have fun.

Discussion

This study provides data from children's drawings and narrations that reflect diverse experiences and multiple realities of orphaned children in an HIV/AIDS context. The emerging themes included risk and protective factors that influence the resilience of children orphaned by AIDS. This study reveals a lack of material and psychological support for children who are orphaned. Similar findings have been reported by Chabilall (2004), Miller and Harvey (2001), Mohangi (2008) and others. Although some of the orphaned children in this study indicated that they received material support from their relatives, there was a notable lack of engagement in loving, caring and emotional bonding relationships between the children and their care-givers. Other studies (Cluver & Gardner, 2007; Chitiyo et al., 2008) report similar findings where children - orphaned by AIDS - risked post-traumatic stress, stigma, isolation and other emotional problems in addition to economic constrains. In this study the children's main concerns, as they talked about their drawings, seemed to be emotional needs, and loving and caring relationships with others.

For this reason the researcher argues, on the one hand, that protective factors encompass the nature of the relationship that orphaned children have with their caregivers, peers, teachers and siblings and, on the other hand, positive traits that include socialisation skills, fantasy and play, problem solving and future expectations. The children foregrounded positive relationships as a significant protective factor. The loving, caring and supportive relationships that the children had with their caregivers and other orphaned children represented protective factors that buffer these orphaned children's resilience to risk. In other studies (Ebersohn, 2008; Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005; Masten, 2001) children used their individual assets, as well as their environmental resources, as factors to promote and to forge a pathway to resilience.

In this research various instances of positive personal traits emerged. Most of the orphaned children appeared to be coping with their situation in an optimistic, future-oriented manner. Indications of future-orientedness were illustrated in their optimism about the future and their aspirations to care for other people. The environmental factors included financial and material needs that contributed to risk factors and to stigma and discrimination experienced by some of the orphaned children. Resilience was apparent in the children in this study, both in terms of problem solving as well as in their desire to establish attachment-relationships as reported in the studies done by Rutter (2000) and Werner (2000).

Conclusion

This study highlights the use of visual methods in exploring the experiences of orphaned children and the situation in which they find themselves vulnerable and how they cope with their situation. In terms of risk, most of the orphaned children were still grieving and they lacked emotional support. The use of drawing in guiding the interview enabled the children to talk about what they felt comfortable revealing to the researcher in a non-threatening way. The theme of 'parental yearning' highlights the material and emotional divide that is created when a parent/s dies and it suggests that children feel insecure in the absence of their parents and parental figures. It further suggests that positive relationships with caregivers, relatives, peers, teachers and siblings are an important factor in fulfilling their emotional and material needs.

The findings of this study suggest the need to foreground positive relationships as a buffer in the lives of children who are orphaned as a result of AIDS. In schools such positive relationships can be with both teachers and peers. Within households positive relationships between caregivers, relatives and siblings may be useful in enabling coping.

Although the children's drawings and narrations revealed experiences of different levels and types of vulnerability, there is an emerging theme that indicates that some children who are orphaned are able to reconstruct their thinking and actions in terms of the future by shifting from a vulnerability mindset to one of agency. The researcher's argument is that in order for orphaned children to become resilient, they may need to: (i) adopt different socialisation strategies; and (ii) use available positive personal traits as ways of meeting emotional and material needs in the absence of their parents. Further research is required to explore both the presence of agency in coping by orphaned children and the role that protective relationships play in addressing emotional and material needs.

References

Atwine B, Cantor-Graae E & Bajunirwe F 2005. Psychological distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine, 61:555-564. [ Links ]

Backett-Milburn K & McKie L 1999. A critical appraisal of the draw and write technique. Health Education Research, 14:387-398. [ Links ]

Bettmann JE 2006. Using attachment theory to understand the treatment of adult depression. Clinical Social Work Journal, 34:531-542. [ Links ]

Bonanno GA 2004. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59:20-28. [ Links ]

Bradshaw D 2005. AIDS the leading killer in the country - report. Daily Sun, 18 May. [ Links ]

Chabilall JA 2004. A social-educational study of the impact of HIV&AIDS on the adolescent in child-headed household. MA dissertation. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Charmaz K 2000. Grounded theory: Objectives and constructivist methods. In NK Denzin & YS Lincoln (eds). Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Chitiyo M, Changara DM & Chitiyo G 2008. Providing psychological support to special needs children: A case of orphans and vulnerable children in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Education Development, 28:384-392. [ Links ]

Cluver L & Gardner F 2006. The psychological well-being of children orphaned by AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Annals of General Psychiatry, 5:1-9. [ Links ]

Cluver L & Gardner F 2007. Risk and protective factors for psychological well-being of children orphaned by AIDS in Cape Town: A qualitative study of children and caregivers' perspectives. AIDS Care, 19:318-325. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2002. Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Denzin N & Lincoln Y (eds) 2000. Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Dockrell J, Lewis A & Lindsay G 2000. Researching children's perspectives: A psychological perspective. In A Lewis & G Lindsay (eds). Researching children's perspectives. Buckingham: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Driessnack M 2006. Draw-and-tell conversations with children about fear. Qualitative Health Research, 16:1414-1435. [ Links ]

Ebersohn L 2007. Voicing perceptions of risk and protective factors in coping in a HIV&AIDS landscape: Reflecting on capacity for adaptiveness. Gifted Education International, 23:149-159. [ Links ]

Ebersohn L 2008. Children's resilience as assets for safe schools. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 18:11-18. [ Links ]

Evans RMC 2005. Social networks, migration, and care in Tanzania: Caregivers' and children's resilience to coping with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Children and Poverty, 11:111-129. [ Links ]

Fergus S & Zimmerman MA 2005. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26:399Â119. [ Links ]

Ferrara MM & Ferrara PJ 2005. Parents as parents: Raising awareness as a teacher preparation program. Clearing House, 79:77-81. [ Links ]

Ferreira R 2008. Using intervention research to facilitate community-based coping with HIV/AIDS. In L Ebersohn (ed.). From microscope to kaleidoscope: Reconsidering educational aspects related to children in the HIV&AIDS pandemic. Rotterdam/Tapei: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Foster G 2002. Understanding community response to situation of children affected by Aids: Lesson for External Agencies. Draft Paper prepared for the UNRISD Project HIV/AIDS and Development. [ Links ]

Fredrickson BL 2001. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56:218-226. [ Links ]

Giese S, Meintjes H, Croke R & Chamberlain R 2003. Health and social services to address the needs of orphans and other vulnerable children in the context of HIV/AIDS in South Africa: Research report and recommendations. Report submitted to HIV/AIDS directorate, National Department of Health. Cape Town, South Africa: Children's Institute, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Holmes J 1993. John Bowlby and attachment theory. London: Brunner-Routledge. [ Links ]

Kangethe S 2009. Critical coping challenges facing caregivers of persons living with HIV/AIDS and other terminal ill persons: The case of Kanye care program, Botswana. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 15:115-121. [ Links ]

Kaplan HB 2005. Understanding the concept of resilience. In S Goldstein & RB Brooks (eds). Handbook of resilience in children. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. [ Links ]

Keyes CLM 2007. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62:95-108. [ Links ]

Kidman R, Petrow SE & Heymann SJ 2007. Africa's orphan crisis: Two community-based models of care. AIDS Care, 19:326-329. [ Links ]

Landry T, Luginaah I, Maticka-Tyndale E & Elkins D 2007. Orphans in Nyanza, Kenya: coping with the struggles of everyday life in the context of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in children &youth, 8:75-98. [ Links ]

Loots T & Mnguni M 2008. Pastoral support competencies of teachers subsequent to memory box making. In L Ebersohn (ed.). From microscope to kaleidoscope: Reconsidering educational aspects related to children in the HIV&AIDSpandemic. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Luthar SS 2003. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Makame V, Ani C & Grantham-McGregory S 2002. Psychological well-being of orphans in Dar El Salaam, Tanzania. Acta Paediatrica, 91:459-465. [ Links ]

Masten AS 2001. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56:227-238. [ Links ]

Merriam SB 1998. Qualitative research and case study applications in education: Revised and extended from case study to research in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [ Links ]

Miller ED & Harvey JH 2001. The interface of positive psychology with a psychology of loss: A Brave New World? American Journal of Psychotherapy, 55:313-322. [ Links ]

Mohangi K 2008. Finding roses among thorns: What about hope, optimism and subjective well-being? Doctoral thesis. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Mokoae LN, Greef M, Phetihu RD, Uys LR, Naidoo JR, Kohi TW, Dlamini PS, Chirwa ML & Holzermer WL 2008. Coping with HIV/AIDS stigma in five African countries. Journal of Nurses AIDS Care, 19:137-146. [ Links ]

Moletsane MK 2008. The psychological effects of orphanhood on children. In L Ebersohn (ed.). From microscope to kaleidoscope: Reconsidering educational aspects related to children in the HIV&AIDS pandemic. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Monasch R & Boerma JT 2004. Orphan and childcare patterns in sub-Saharan Africa: An analysis of national surveys from 40 countries. AIDS, 18:S55-S65. [ Links ]

Ogina TA 2008. How teachers understand and respond to the emerging needs of orphaned children. In L Ebersohn (ed.). From microscope to kaleidoscope: Reconsidering educational aspects related to children in the HIV&AIDS pandemic. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Robson S & Kanyanta SB 2007. Moving towards inclusive education policies and practices? Basic education for AIDS orphans and other vulnerable children in Zambia. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11:417-430. [ Links ]

Rutter M 2000. Resilience reconsidered: Conceptual considerations, empirical findings and policy implications. In JP Shonkoff & SJ Meisels (eds). Handbook of early childhood intervention (2nd ed). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sengendo J & Nambi J 1997. The psychological effect of orphanhood: A study of orphans in Rakai district. Health Transition Review, 7:105-124. [ Links ]

Smit R 2007. Living in an Age of HIV and AIDS: Implications for families in South Africa. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 16:161-178. [ Links ]

Stake RE 2000. Case studies. In NK Denzin & YS Lincoln (eds). Handbook of Qualitative Research (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Townsend L & Dawes A 2007. Intentions to care for children orphaned by HIV&AIDS: A test of the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37:822-843. [ Links ]

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS], United Nations Children's Fund [UNICEF] & United States Agency for International Development [USAID] 2004. Children on the brink 2004: A joint report on orphan estimates and a framework for action. New York: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Van Wyk N & Lemmer E 2007. Redefining home-school community partnership in South Africa in the context of the HIV&AIDS pandemic. South African Journal of Education, 27:301-316. [ Links ]

Werner EE 2000. Protective factors and individual resilience. In JP Shonkoff & SJ Meisels (eds). Handbook of early childhood intervention (2nd ed). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Young L & Barret H 2001. Adapting visual methods: action research with Kampala street children. Area, 33:141-152. [ Links ]

Yuen FC 2004. "Its was fun...I like drawing my thoughts": Using drawing as part of the Focus Group Process with Children. Journal of Leisure Research, 36:461-482. Available at http://findarticle.com/p/article/_qa3702/is_200410ai. Accessed 20 April 2007. [ Links ]

Zhang JH 2007. Of mother and teachers: Roles in a pedagogy of caring. Journal of Moral Education, 36:515-526. [ Links ]