Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.32 no.4 Pretoria Jan. 2012

Picture that: supporting sexuality educators in narrowing the knowledge/practice gap

Christa Beyers

School of Educational Studies, University of the Free State, South Africa BeyersC@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Teaching about sex and relationships is one of the greatest challenges in not only the combating of HIV and AIDS, but also in preparing the youth for responsible sexual behaviour. Although it seems as if teachers to some extent do feel comfortable with the teaching of sexuality education at school, the question however remains as to whether youth get the information they require. In this article, I present drawings produced by teacher participants in order to investigate the beliefs that teachers hold regarding young people's needs from sexuality education. As a result of the findings from this study, I will argue that teachers do have a sound knowledge of what contributes to promiscuous sexual behaviour and what is required to narrow the knowledge/practice gap, as discussed by Allen (2001), but they still want to teach what they find acceptable. I will attempt to interrogate the knowledge/practice gap from the 'other side' - what do teachers base their beliefs on when deciding what content is appropriate to teach in sexuality education and their understanding with regard to what youth require from sexuality education in the classroom.

Keywords: knowledge/practice gap; participatory visual methodology in sexuality education

Introduction

Participatory visual methodologies have captured the attention of researchers in the social sciences as innovative research method. Taylor and Coffey (2008:8) define innovation as 'the creation of new designs, concepts and ways of doing things', De Lange and Stuart (2008:131) add to this notion when stating that visual and participatory elements for research designs have 'a built-in intervention orientation' where drawing is viewed as a natural means of communication which could assist participants to organise their thoughts and explore ideas in order to make sense of their world. In this paper drawings might move teachers to reconsider what they teach in the sexuality education classroom.

When I decided on the use of drawings as method to generate data, there were several factors that I needed to take into account. Firstly, as noted by Taylor and Coffey (2008), it was essential to be convinced that the method is not just a gimmick. The researcher must have the conviction that it should serve as a genuine quest to improve aspects of the research process; in this study, the purpose of using drawings is to elicit true perceptions of the participants' views on sexuality issues. Secondly, the researcher should never make the assumption that she can interpret drawings in order to understand the emotions, thoughts and feelings of the 'artists'.

While drawings offer a potentially rich view of the participants' world, Coates and Coates (2006) warn that the researcher should guard against viewing and interpreting the drawings from within their own social context. Therefore, the researcher should also act as participant and be a part of the interpretation in order to establish what the drawings might reveal about social issues - in this paper, sexuality education - which need to be addressed in the South African context. Participants in this study were actively engaged in the data collection process, while the researcher observed and took notes of communication and interaction between participants. When the participants started to 'show and tell', the researcher ensured that meaningful discussions took place by follow-up questions/prompts which created more dialogue and data about the topic in question. Participants therefore were enabled to take control of their understanding of sexuality education, analyse the situation and devise their own solutions. Drawings should thus be viewed as a participatory method that assists the participants in not only communicating complex messages, but also in reflecting on their own experiences and exploring personal plans for development - this stresses Mitchell's (2008) notion that visual data should have the possibility to mobilise individuals and communities to act in order to effect social change. To accomplish this, it is important to use drawings in combination with writing and/or conversation. Another factor to consider when using drawing as method is to ensure that knowledge will be produced in the process. Drawings are viewed as a point of reference from which participants are encouraged to participate in the analysis of the meaning embedded in the drawing. The discussion of the meaning of the drawing often prompts further data which may create opportunities to discover new ideas.

In this paper drawing as method is used to empower teachers to identify social issues with regard to the sexual behaviour of youth but, moreover, to understand what they can contribute towards possible solutions from their understanding about sexuality, with the drawings as visual products of this outcome.

The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, it seeks to narrow the knowledge/practice gap, as proposed by Allen (2001), by assisting teachers to understand what they base their beliefs on when deciding what content is appropriate to teach in sexuality education. Second, it seeks to enable teachers to employ this method when teaching sexuality education in the classroom in order for them to reconsider the content taught in the sexuality education classroom.

Background to the study

According to the International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education (UNESCO, 2009), few adolescents receive adequate information to prepare them for responsible adulthood, which leaves them vulnerable to sexual abuse, coercion, unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV and AIDS. Even though the majority of youth in South Africa seem to have sound knowledge about sexual health risks (Reproductive Health Research Unit, 2004) and an awareness of HIV and AIDS (Desmond & Gow, 2002), this knowledge doesn't seem to have a positive influence on their sexual behaviour. Risky sexual behaviour is one of the major factors in the increasing rate of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV, among adolescents (Rogow & Haberland, 2005).

Although debates about the sexual behaviour of youth typically focus on sexual intercourse and its negative consequences, young people tend to find information about relationships and intimacy from a much wider framework. The Henry J. Kaizer Family Foundation (2007) reported that almost 70% of television shows contain inserts with sexual content, and Collins, Martino and Shaw (2011) found that sexting (sending and receiving sexual messages and photos on their cell phones) is practised by at least 50% of youth aged 13-19 years. Brown (2002) adds to this concern when revealing that the word 'sex' is the most popular item searched on the Internet today.

Nonetheless, sexual feelings are fundamental to adolescent development. Understanding and addressing the needs that youth have with regard to the content of sexuality education is an essential step towards curtailing the spread of HIV. Furthermore, discussing sexual behaviour could assist youth to understand that they can enjoy sexual feelings without acting on them. This, unfortunately, does not always become a reality, because adults tend to want to teach what they deem important. In a study that aimed to assess whether teachers felt comfortable in teaching sexuality education, Peltzer and Promtussananon (2003) found that teachers felt moderately at ease teaching learners about sexuality. Furthermore, teachers are reported to have sound knowledge of HIV- and AIDS-related topics (Theron, 2005).

Why is it, then, that the sexual behaviour of youth does not change to become responsible? Dailard (2001) argues that the teaching of conservative abstinence-only content is way off the mark, and proposes that more controversial topics such as birth control, abortion and sexual orientation should be addressed. Allen (2001) supports this notion when stating that, despite the fact that youth receive information on how to avoid STIs and unplanned pregnancies, their lifestyle does not reflect this knowledge. This suggests that sexuality education is somehow flawed and that there is a need for a shift in the way information is disseminated as well as for reconsidering the content taught.

The knowledge/practice gap

Allen (2001) acknowledges the following two ways in which youth obtain sexual knowledge: from secondary sources such as sexuality education and knowledge obtained from personal experience. Young people need reliable information regarding sexuality issues to be able to withstand the pressures to have sex too soon and to have healthy, responsible and mutually protective relationships when they do become sexually active. Aggleton (1997) notes in this regard that sexual health is viewed by adults as the absence of STIs, HIV and unplanned pregnancies. Allen (2004:109) made a noteworthy contribution to sexuality education when she explored the benefits of adding a 'discourse of erotics' in sexuality education which could lead to sexual health. She stresses that the inclusion of information on sexual pleasures and desires does not exclude the teaching of unwanted outcomes of sexual activity (Allen, 2001). To be viewed as sexually healthy, a person should have adequate knowledge regarding the physical aspects of sex but, more importantly, youth should have well-defined sexual boundaries.

The messages that the youth gain about themselves and the choices that they make with regard to sexuality are crucial. According to Mukoma, Flisher, Helleve, Aar0, Mathews, Kaaya and Klepp (2009), sexuality and HIV/AIDS intervention programmes often do not yield the positive results needed for healthy sexuality as teachers are often not comfortable teaching safe sex and prefer to teach abstinence. Very often adults think that by giving youth relevant sexual information they are, in effect, giving youth permission to engage in unsafe sex practices. In this regard, it is the conviction of the researcher that sexuality programmes should be reframed with less emphasis on biological aspects of sexuality, in favour of the earlier emphasis on the social context in which sexual attitudes form and decisions are made. This can only be achieved if teachers and adults are willing to engage with youth in a way that keeps pace with the changing roles of the youth as active, informed participants in society. The use of drawings might just add to this call.

Rogow and Haberland (2005) postulate that sexuality education should include the development of critical thinking skills and emphasise learning and reflection on social aspects (such as race and gender) which affect sexual behaviour. The World Health Organisation contends that all people have the right to sexuality education 'that addresses the socio-cultural, biological, psychological and spiritual dimensions of sexuality by providing information; exploring feelings, values and attitudes; and developing communication, decision-making and critical thinking skills' (Shabi & Shabi, 2011). Sexuality issues such as gender differences, homosexuality, gender-based violence, mutual masturbation, sex play and sexual minorities are fundamentally social issues. Presently, these topics are often ignored or ineffectively addressed (Allen, 2001; 2004; Francis, 2010; 2011).

According to Pettifor, Rees, Steffenson, Hongwa-Madikezela, McPhail, Vermaak and Kleinschmidt (2004), the high HIV and AIDS prevalence rates of youth between the ages 14 and 24 have added urgency to ascertain what the knowledge gaps are between what youth get and what they need with regard to sexuality education. However, in a context where ignorance and misinformation can have a profound effect on the protection and well-being of learners, as well as in recognition of the social nature of sexual relations, it is vital to adhere to the proposal of United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] (2008) to promote critical thinking skills and reflect on social context which affect sexual behaviour. My study endeavours to contribute to this discussion by posing three questions: (1) What knowledge do teachers have about the sexual behaviour of youth? (2) What do they understand regarding the youth(s needs from sexuality education? and (3) What content do teachers view as appropriate to teach in sexuality education?

With this paper I will argue that teachers, even though they are aware of the factors leading to adolescent irresponsible sexual behaviour, teach what they find acceptable, in a way they find acceptable, and not what is needed by youth, adding to the widening of the knowledge/practice gap.

Handing over the power: from teacher to learner

By 'handing over the power' I propose that adults make the shift towards giving youth the power to learn from them what they need, instead of thinking that they (the adults) know what is appropriate content to teach with regard to sexuality education. With the high incidence of HIV-positive individuals in South Africa, teachers (and adults) do not have a choice in making sexuality education more relevant and effective. When taking into account where youth derive their information from (such as TV, Internet and cell phones) there is a clear need to broaden the reach of sexuality education to a younger audience, addressing the issues that they are interested in.

Although Zisser and Francis (2006) report that youth feel at ease to speak to teachers about sexuality, dependence on teachers to instil these lessons may be problematic, as teachers teach what they feel comfortable with. Helleve, Flisher, Onya, Mukoma and Klepp (2009) concur by stating that teachers often choose not to teach specific sexual knowledge because it may differ from their own perspective and cultural values. Although teachers are identified as a reliable and trusted source for sexuality education, in many cases, they have not responded accordingly (Coetzee & Kok, 2001; Rugalema & Khanye, 2002; Baxen & Breidlid, 2004).

In South Africa, sexuality education mainly focuses on abstinence and rote learning, although Kirby, Laris and Rolleri (2005) emphasise that teaching methods that actively involve the participants and help them to personalize the information is one of the key characteristics of an effective sexuality programme. Although the focus of this paper is on the perceptions of teachers, it is the ideal that teachers could find this project meaningful, to the extent that they see the value in the use of drawings as method to actively involve youth and assist them in personalising information with regard to sexuality education in their classes. If so, it could be the first step in narrowing the gap between what teachers teach and what youth need in sexuality education. If the use of drawings as method can assist youth in analysing the social forces underlying sexual relationships, the teaching about sex and related issues might just become less complex.

The research process

This study, which is an interpretive qualitative study (Merriam, 1998), seeks to understand how teachers make meaning of sexuality education from their own perspective. By using drawings as visual participatory method, the teachers who participated in the study, could take some control of the research process and prioritize issues that a researcher might not deem relevant. As a participant-researcher, I took part in interpreting the drawings in an attempt to establish what the drawings might reveal about issues of sexuality education which need to be addressed within the South African context. I became a learner and a facilitator, and acted as catalytic agent in the process where participants took part in the discussing and analysis of their drawings. My role as facilitator was to maintain group focus on what I tried to accomplish with the research, as well as encourage participants to feel personally invested in the process and its outputs.

A total of 20 teachers participated in the study with their ages ranging between 24 and 49. These teachers were enrolled for the BEd Hons in Inclusive Education. The sample was purposive in so far as all the educators were registered for an HIV/AIDS Education module while all of them were also teaching Life Orientation (including sexuality education) in the senior level (Grades 7-10). These teachers were invited to take part in the project, and their participation was voluntarily. I followed a consequentionalist approach as I assessed that the outcomes could benefit the group and perhaps influence their method of teaching sexuality education. I did however expect the participants to sign an informed consent form and I guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity. Ground rules were also laid down about respecting confidentiality which created a safe space for all participants to produce drawings that might be personal or revealing. Participants were informed about the reason for the activity. They were then handed an A4 sheet of paper and a gel pen. I used the following prompt to elicit drawings: Make a drawing that represents your view on youth engaging in unsafe sexual practices. You may draw anything that comes to mind (it is not important how well you draw, but what you draw). This brief was chosen because I believe that if the participants understood from their own perspective what leads to unsafe sexual behaviour of youth, the discussion afterwards would clarify what they viewed as possible solutions to this problem from the perspective of sexuality education teachers.

After the participants had completed their drawings, I asked them to provide written explanations of their drawings, and also what content they believe is appropriate to teach in the sexuality education classroom. Participants were then given the opportunity to 'show and tell' in order to explain their drawings. This session lead to lively discussions, but most rewarding was when one of the teachers said: 'This could really work in my class'. If teachers can see the potential in making use of drawings in their classrooms, this could open the way for more effective sexuality education.

The qualitative data were analysed by examining the 'three flows of activity', as proposed by Miles and Huberman (1994:10), namely, data reduction, data display and conclusion drawing/verification. Data reduction starts at the beginning of the study and continues throughout the collection process. The researcher and participants engage in speculation, while searching for meaning in the data (pictures) and reflecting on the literature. This speculation leads the researcher to make new observations and ask prompting questions and, together with the participants, look for patterns to paint the full picture. The drawings should be seen as a starting point for developing personal thoughts and experiences about sexuality education. This creative activity then enabled the participants in a meaningful way, to communicate and reflect on what their drawings meant with regards to understanding sexual behaviour of youth as well as possible solutions to address these issues in a sexuality education classroom. When participants displayed their pictures, the whole group could add to the understanding of what they saw. This could also be viewed as a reflective process where the data and discussion thereof could be the result of thoughtful reflection. In this study, the trustworthiness was enhanced by rich description of the drawings, the sharing of the meaning, literature control and the retaining of all data. The limitation of this project was that only a small proportion of teachers were involved, which implies that a limited range of images are presented. According to Guillemin (2004) people primarily use words to make meaning of social issues; therefore it may be difficult for participants to express themselves using drawings, which again emphasises the importance of the discussion to give meaning to the picture. It could also be viewed as limitation that drawing took place in a group setting, as it is possible that participants give voice to what they deem socially acceptable, and not what they themselves believe.

Discussion

It seems 'logical' to assume that if teachers have knowledge and understanding of factors contributing to risky sexual behaviour of youth, they have a good idea of what content to teach in their classrooms. The reality is however that sexual behaviour cannot be equated to 'right and wrong' answers, as many teachers propose in their sexuality education classes. While it is important for teachers to have knowledge and thus feel at ease to address sexuality, we cannot ignore the fact that teachers' knowledge is their own conceptualization of it. By understanding their subjective knowledge of sexuality we might just pave the way for extending the content taught, which could assist in narrowing the knowledge/practice gap.

Most participants drew pictures that focused on social determinants of adolescents' sexual behaviour. Youth are frequently depicted as wanting to experiment, such as the drawing 'Experimentation until it reaches boiling point'. Experimentation in this regard was also called 'ignorance' and included aspects such as sex, alcohol and drug abuse. I present two drawings as representative thereof (see Figure 1).

Peer pressure, which is linked to experimenting, was also considered a contributing factor to promiscuous sexual behaviour. One participant mentioned that youth don(t want to use condoms as they believe 'sex has to be flesh to flesh'. The drawing (Figure 2) shows how adolescents are viewed as engaging in sexual relationships because they are laughed at if they don't conform. Even though the Henry J. Kaizer Family Foundation (2007) reports that youth believe waiting to have sex is a good idea, few of them actually do, which again raises the question of why sexuality education does not sufficiently support the youth. During the group discussion one participant said 'Young people want to experiment because the truth and realities behind things are hidden from them'. From this it is clear that certain 'realities' are not communicated to youth. This is in direct contrast to the view of Mitchell, Walsh and Larkin (2004:36) who argue that 'youth have the right to relevant information about their own bodies and their sexuality'. Although one participant said that 'they should be told the truth and realities about sex and sexual behaviours' this participant mentioned that this included the importance of sex but at the right time and proper age. Moreover, participants were of the opinion that youth should be taught content which would promote healthy lifestyles and protect them against immoral sexual behaviours. This emphasises the point made by Allen (2001) that what teachers view as important, should be viewed from their own social agency.

Six drawings could be linked to what participants explained as 'it's our culture'. When prompted, it became clear that they did not view culture as a cause for unsafe behaviour, but that they believed that it is not culturally appropriate for adults to talk about sex. It was mentioned that youth engage in risky sexual behaviour because parents and teachers shy away from giving youth information about sex. This adds to the notion of Francis (2011) that topics related to sexuality are often ignored or ineffectively addressed. Apart from the drawings with the word 'Culture', there was also the interesting drawing of male and female genitalia (see Figure 3). Although the direct approach of the drawing would not be culturally acceptable in conversation, it does however prove that making use of drawing as method could open possibilities to allow the discussion of taboo topics. When we discussed this drawing, it became clear that the participants felt comfortable in discussing only the biological aspects of the drawing. It was furthermore mentioned that there are things to consider in order to practise safe sex, such as 'how does one become affected and infected, and physical changes in the body'. Participants further emphasized the teaching of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), but also included skills such as problem-solving as well as decision-making skills. One participant said '(learners) should be aware that HIV and AIDS are there, and it's not curable, so it's ones responsibility to take care of him/herself. This notion revisits what researchers (Aggleton, 1997; Allen, 2001; Francis, 2010) warn against - the physiological route.

Four participants' drawings reflected the notion that family life has changed from two-parent to single-parent families (see Figure 4). The drawing showed two people 'in love', but another two in a circle. The three children were scratched out. During the 'show and tell' session, participants voiced that learners do not value a marriage and children, because many youth don't experience these in their homes. This should also be linked to the drawing where a participant added that bad role models( (see Figure 5) contributed to the ignorance of youth when it comes to sex. Although the drawing depicted the dress code of female teachers that 'invokes sexual fantasy on the male learner', it was however mentioned by all participants during the discussion, that it is not only restricted to teachers, but that many people, also parents and family members, could be viewed as bad role models. Issues such as clothing, especially with adolescents, could be as significant an issue as sex without marriage, and teachers should present such issues in a manner that does not reflect their own understanding of sexuality. Teachers should take care to distinguish between facts and personal beliefs. Information about sex is important, but effective sexuality education should include information about feelings, communication, boundaries and building relationships as well. When prompted, it was clear that teachers felt that men are more likely to have sexual relations outside of a marriage. As one participant said 'how can learners distinguish between right and wrong if they are confronted with this' (infidelity). Furthermore the issue of gender was addressed when a teacher mentioned that girls like to be popular and they like to be seen in nice cars, therefore they engage in risky sex, 'especially with older, married men'. These comments again raised the concern of disempowered people, especially women who tend to think they cannot take control over their health (Zisser & Francis, 2006). Participants proposed that the focus of sexuality education should be on religious education, values and accepted behavioural activities (norms): 'the Word of God is so important because the learners are to realize the God's will about them and they will want to do good'. It cannot be denied that religion and religious practices have an important role to play in the holistic development of learners (Clough & Holden, 2002), including the development of sexuality, but Francis (2011) warns against oversimplifying the age group as youth are faced with a multitude of risks and opportunities that influence their sexual behaviour, such as social background, gender, ethnicity and culture. Moreover, teachers must keep in mind that many of the youth hold different religious beliefs regarding sex, varying from complete abstinence to engaging in safe sex. It must be kept in mind that the knowledge teachers have regarding their own sexuality should not be mistaken as what youth need.

Three drawings focused on the role of the media in the sexual behaviour of learners (see Figure 6). Participants verbalised that learners are allowed to watch anything and 'they can't differentiate between right and wrong'. When taking into consideration what The Henry J. Kaizer Foundation (2007), Collins et al. (2011) and Brown (2002) mentioned with regard to where youth find their information, this is a valid point. This should serve as a clear indication that youth are indeed searching for information which they do not find at home or at school.

Four drawings focused on a holistic view of the 'learner as system'. Learners are depicted as a 'Tree of Life - being part of a system where many factors may lead to promiscuous sexual behaviour (see Figure 7). The 'artist' explained that 'adolescents are attracted by love, feelings, alcohol, growing up and peer pressure. In addition, environmental circumstances and poverty were also mentioned as having an impact on youth's sexual behaviour. The drawing had its roots in the ground with the word 'Life' added. This was clarified during the discussion session when the participant said that one 'needs to have strong roots to stand up to life's challenges'.

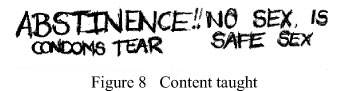

One participant made the drawing depicted in Figure 8. She mentioned, when discussing the drawing, that youth are not given the 'right' information, which in her opinion was to abstain, because the only safe sex is no sex. When asked what participants viewed as appropriate content to teach, most teachers agreed that learners should be taught the ABC (Abstinence - Be faithful - use Condoms) as proposed by the National HIV/AIDS Campaign. According to the participants, learners should be taught 'that it is OK to have sexual feelings at a certain age, but they should be trained to make informed decisions concerning their lives and be assertive - to say no to things which may put them in trouble'.

Narrowing the gap

Wood (2008) is of the opinion that we are all shaped by our culture and life experiences, and that our behaviour is determined by what we are taught. Data collected for this study revealed that most teachers have adequate knowledge regarding factors that influence sexual behaviour of youth, but they still want to prescribe, rather than focus on what youth need. I argue that this demands of teachers to put aside their own cultural notions regarding sex and sexuality education and equip themselves to take the needs of youth into account when attempting to narrow the knowledge/practice gap.

If teachers could be enabled to make use of drawings in the classroom, it may assist them in beginning the process of reflecting on what youth think and need in sexuality education. As De Lange and Stuart (2008:132) rightfully state: 'for many, it will be the first time they have been able to trap and examine those thoughts'. The role of the teacher is therefore not to decide which cultural premises to proclaim, but to focus on the issue that is destroying so many lives of young people who do not have access to the knowledge so desperately needed. Learners do not live in a vacuum, but are part of a society that determines the interpretation of culture and norms. It is inevitable that sexuality educators need to define what cultural practices are essential in dealing with the pandemic, and disregard those that do not contribute to the cause. To narrow the knowledge/practice gap would expect teachers to put aside their own notions of what and how to teach, and make use of alternative teaching methods such as the use of drawings to understand what youth require from sexuality education. This could address Vay-rynen(s (2003) concern that even though teachers seem eager to participate in a changing environment, the transformation seemed to stagnate at a certain point: the rigidity of teaching/ learning practices. Added to this, it would be ignorance to think that these views of teachers are the answer to healthy sexuality of youth. We would lose a sense of young people's agency (Allen, 2001).

Conclusion

In this article I outline the use of participatory visual methodologies, specifically the use of drawing, as a tool towards social change in the context of sexuality education. Although the drawings aided in eliciting emotions and feelings, I feel that the discussions afterwards should be viewed as essential as these lead to a more accurate presentation of what the drawings depicted. In this paper, the use of drawings attempted to provide insight into teachers' understanding of what youth require from sexuality education.

I am convinced that these drawings revealed that teachers do have sound knowledge of not only factors contributing to unsafe sexual behaviour by adolescents, but also content which should be addressed to narrow the knowledge/practice gap. The concern is that they still teach sexuality from their own conceptualization thereof. The use of drawings has considerable potential to assist teachers and learners in critically reflecting on healthy sexuality and could pave the way for discussion and dialogue to prepare the youth for one of the greatest challenges in humanity: responsible sexual behaviour (UNESCO, 2009).

References

Aggleton P 1997. Success in HIV prevention: Some strategies and approaches. Horsham: AVERT. [ Links ]

Allen L 2004. 'Beyond the birds and the bees: Constituting a discourse of erotics in sexuality education'. Gender and Education, 16:151-167. [ Links ]

Allen L 2001. Closing sex education's knowledge/practice gap: The reconceptualization of young people's sexual knowledge. Sex Education, 1:109-122. [ Links ]

Baxen J & Breidlid A 2004. Researching HIV/AIDS and education in sub-Saharan Africa: Examining the gaps and challenges. Journal of Education, 34:9-24. [ Links ]

Brown JD 2002. Mass media influences on sexuality ( statistical data included. Journal of Sex Research. Available at: http://www.google.co.za/search?hl=en&client=firefox-a&hs=Znx&rls=org.mozilla%3AenZA%3Aofficial&channel=np&q=Brown+J+2002.+Mass+media+influences+on+sexuality+%E2%80%93+statistical+data+included. +Journal+of+Sex+Research.+&oq=Brown+J+2002.+Mass+media+influences+on+sexuality+%E2%80%93+statistical+data+included.+Journal+of+Sex+Research. +&gs_l=serp.3...8143.8143.0.8445.1.1.0.0.0.0.0.0..0.0...0.0...1c.1.59X_CLi3EJY. Accessed 5 February 2012. [ Links ]

Clough N & Holden C 2002. Education for Citizenship: Ideas into action. London: RoutledgeFalmer. [ Links ]

Coates E & Coates A 2006. Young children talking and drawing. International Journal of Early Years Education, 14:221-241. [ Links ]

Coetzee A & Kok JC 2001. What prohibits the successful implementation of HIV/AIDS, sexuality and life-skills education programmes in schools. South African Journal of Education, 21:6-10. [ Links ]

Collins RL, Martino SC & Shaw R 2011. Influence of New Media on Adolescent Sexual Health: Evidence and Opportunities. Working Paper April 2011. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/11/AdolescentSexualActivity/NewMediaLitRev/. Accessed 22 March 2012. [ Links ]

Dailard C 2001. Sex Education: Politicians, Parents, Teachers and Teens. The Guttmacher report on Public Policy, 4:9-12. [ Links ]

De Lange N & Stuart J 2008. Innovative teaching strategies for HIV and AIDS prevention and education. In L Wood (ed.). Dealing with HIV and AIDS in the classroom. Cape Town: Juta & Company Ltd. [ Links ]

Desmond C & Gow J 2002. The current and future impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on South Africa's children. In GA Cornia (ed.). AIDS, public policy and child well-being. New York: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Francis DA 2011. I would tell no one because it is for me to know ... No one! Whom do out-of-school youth talk to about decisions regarding voluntary counselling and testing? The Indian Journal of Social Work, 72:55-70. [ Links ]

Francis DA 2010. Sexuality education in South Africa: Three essential questions. International Journal of Educational Development, 30:314-319. [ Links ]

Guillemin M 2004. Understanding illness: Using drawings as research method. Qualitative Health Research, 14:272-289. [ Links ]

Helleve A, Flisher AJ, Onya H, Mukoma W & Klepp KI 2009. South African teachers' reflections on the impact of culture on their teaching of sexuality and HIV/AIDS. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 11:189-204. [ Links ]

Kirby D, Laris BA & Rolleri L 2005. Impact of sex and HIV education programs on sexual behaviours of youth in developing and developed countries (Youth Issues Research Working Paper No. 2). Research Triangle Park, NC: Family Health International. [ Links ]

Merriam SB 1998. Qualitative research and case study applications in education (2nd ed). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Miles MB & Huberman AM 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Mitchell C 2008. Getting the picture and changing the picture: Visual methodologies and educational research in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 28:365-383. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, Walsh S & Larkin J 2004. Visualizing the politics of innocence in the age of AIDS. Sex Education: Sexuality, Society & Learning, 4:35-47. [ Links ]

Mukoma W, Flisher AJ, Helleve A, Aar0 LE, Mathews C, Kaaya S & Klepp KI 2009. Development and test-retest reliability of a research instrument designed to evaluate school-based HIV/AIDS interventions in South Africa and Tanzania. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 37:7-15. [ Links ]

Peltzer K & Promtussananon S 2003. HIV/AIDS education in South Africa: Teachers' knowledge about HIV/AIDS: Teacher attitudes about and control of HIV/AIDS education. Social Behaviour and Personality, 31:349-356. [ Links ]

Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Steffenson A, Hongwa-Madikezela L, MacPhail C, Vermaak C & Kleinschmidt I 2004. HIV and sexual behaviour among young South Africans: A national survey of 15-24-year-olds. Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand. Reproductive Health Research Unit 2004. National HIV and Sexual Behavior Survey of 15-24 year olds, 2003. [ Links ]

Rogow D & Haberland N 2005. Sexuality and relationships education: Toward a social studies approach. Sex Education, 5:333-344. [ Links ]

Rugalema G & Khanye V 2002. Mainstreaming HIV/AIDS in the education systems in sub-Saharan Africa: Some preliminary insights. Perspectives in Education, 20(2):20-36. [ Links ]

Shabi IN & Shabi OM 2011. Bridging the gap in adolescent sexuality education: Challenging roles for librarians. Journal of HospitalLibrarianship, 11:45-58. [ Links ]

Taylor C & Coffey A 2008. Innovation in qualitative research methods: Possibilities and challenges. Cardiff: Cardiff University. [ Links ]

The Henry J. Kaizer Family Foundation 2007. HIV/AIDS Policy Fact sheet: The HIV/AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Available at: http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/3030_09.pdf. Accessed 5 February 2012. [ Links ]

Theron LC 2005. Educator perception of educators' and learners' HIV status with a view to wellness promotion. South African Journal of Education, 25:56-60. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 2008. Review of sex, relationships and HIV education in schools. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 2009. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education: An evidence-informed approach for schools, teachers and health educators. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Vayrynen S 2003. Participation equals inclusion? Perspectives in Education, 21(3):39-46. [ Links ]

Wood L (ed.) 2008. Dealing with HIV and AIDS in the classroom. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Zisser A & Francis D 2006. Youth have a new attitude on AIDS, but are they talking about it? African Journal of AIDS Research, 5:189-196. [ Links ]