Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.32 no.4 Pretoria Jan. 2012

How youth picture gender injustice: building skills for HIV prevention through a participatory, arts-based approach

(continued)

Cycle 2: What did participants think they could do about gender injustice?

The analysis of the explanations given for the drawings and the subsequent focus group discussion revealed that participants did have ideas about how they could address gender injustice. However, most of these were likely to be ineffectual, given the fact that the adults around them did not value their input.

Sometimes we see in our communities there is a man hitting a woman in the streets, but other people just laugh at it cos they are used to it. And to stop it...they just laugh at you, say you are too young, just go... (Male, 15). Most of the times you cannot even talk about how to change it. People live in a community where they don't feel compassionate for one another; you just look for yourself (Female, 17).

Most of the suggestions involved "calling a community meeting", "talking to parents to tell them to solve their problems", "tell people to respect each other", "send them for counselling", "teach about gender violence", "stand up to parents", "women must learn to be independent" and so on, but in the light of the subordinate position of the children in the community, it is unlikely that any of these suggestions would actually make any difference, even if they could be implemented. They do not take into consideration the entrenched cultural and structural factors that drive gender power imbalances (Sherr, Mueller & Varrall, 2009).

However, as discussion progressed and I challenged these suggestions, other ideas began to emerge, which were indicative of a slowly growing realisation that they could have agency, if they focused on internal, rather than on external change:

You can change yourself if girls are washing the floor, you can offer to help (Male, 17).

I just feel I could hit that man hitting the woman, but this is not the solution we have to help each other, and do things that will make people happy (Male, 17).

I will not hit my wife or abuse the children when they have done something wrongI will tell them (Male, 14).

I am going to teach my child when going to their work [that] they must wash dishes and floors and cook. I want to teach my children not to bully other children at school. I will never talk strong language in front of my children (Female, 16).

The mixed groups allowed attention to be focussed on the behaviour of both males and females, an important aspect of gender education (Sherr et al., 2009). This growing acceptance of their own agency provided a strong base, from which they could begin to develop interventions in their school community - facilitated through photo-voice and peer interventions.

Cycle 3: What did participants do to promote awareness and change?

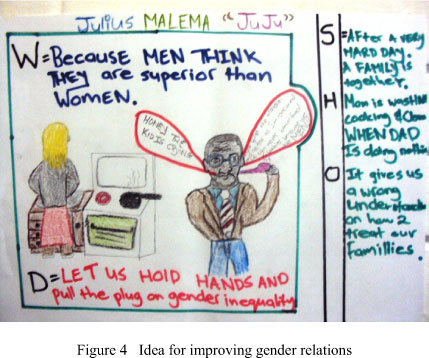

Photo-voice was used with the participants to generate images around ideas for addressing gender issues in their school. They produced powerful images, which focused on specific issues in their community that they believed were representative of the gender injustices they experienced in their communities on a daily basis. The -written explanations offered ideas on how a specific issue could be addressed. Two examples given below are indicative of the agency that the participants were beginning to take to influence their peers:

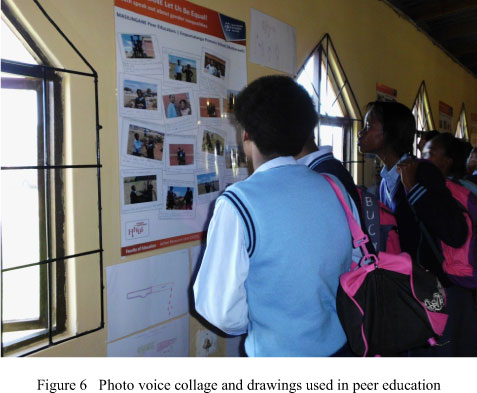

They decided which photographs and explanations best portrayed their prevention messages; and these were made into a laminated poster collage, copies of which they used to display at their schools and at specific peer education events, in order to raise awareness and encourage discussion. The drawings and short narratives were also laminated for display purposes.

The participants also had the opportunity of conveying their message at a Youth Day, part of the international Social Aspects of HIV and AIDS-Research Alliance (SAHARA) conference on the social aspects of HIV and AIDS. They were given free rein by their teachers to develop a short workshop around the theme of the conference: "Turning the Tide" on HIV and AIDS. The content and aim of the workshop is given in Table 1.

The participants presented a varied programme in two different workshops, including educational skits about the different aspects of violence against women, poetry, short dramas and role plays, which conveyed what they had experienced in the community, and also what they thought should be done to turn the tide. Two of the participants acted as continuity presenters, linking the various aspects to each other, to the social reality experienced by youth in the townships, and to ways to change the situation.

The participation by the audience, some of whom were international academics, was lively; and the discussion on how to "turn the tide" was robust. Visual evidence of these workshops is available at http://aru.nmmu.ac.za/Projects/Masilingane-Project-II, including feedback from the audience that indicates that the workshop was successful in raising awareness on gender issues, and in motivating people to think about how they could take action to address these issues.

Following their workshops at the conference, the participants continued to conduct peer education at their schools, by inter alia, displaying the drawings and posters, talking at assemblies, and by repeating their workshops at the school and at events to which parents were invited (see Figure 7).

It is difficult to capture in text the enthusiasm, passion and authentic engagement created by these interventions, and the confidence with which these young people engaged in discussion with peers and other audience members.

Two reflective focus group sessions were held with the learners a few weeks after they had presented their workshop at a school/community event. The two main questions posed to participants were: What have you learnt from being on this project? and How do you now feel about your ability to be an effective peer educator on gender?

Cycle 4: Reflecting on the experience

The focus-group participants indicated that they now enjoyed a heightened sense of self-efficacy to address gender issues and to be peer educators. The main themes of these comments are summarised in Table 2 with a few examples to illustrate.

The increase in self-efficacy levels is evident from these themes, and from the visual data. The participatory nature of the project allowed the participants to experience the four elements that contribute to building self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997):

Mastery experiences: the structured support provided by the action-research process allowed the participants to slowly gain skills and confidence, as they were being facilitated through the different exercises - to raise their awareness levels on gender injustices, and to begin to think how they could address it. The completion of the drawings, their participation in the photo-voice exercises, and the interactive presentations were all mastery experiences in themselves, as the participants successfully negotiated each phase.

Social modelling: the teamwork required for the project, particularly the creation of the workshops and peer presentations, meant that the participants had an opportunity to witness peers successfully modelling the required behaviour.

Social persuasion: during the project, participants were encouraged by the positive feedback of the facilitators, the teachers and each other for their efforts. At the conference, confidence was further boosted when a few of the academics spontaneously praised the participants for an excellent workshop. Each time they acted as peer educators, they received encouragement in the form of positive feedback from their audiences.

Positive emotional environment: engagement with the visual and arts-based methods provided opportunity for fun and laughter, in spite of the sensitive and serious nature of the topic. The sessions with the participants were characterised by a positive emotional climate; and this helped to enhance their learning and to increase their motivation for what they were doing

Throughout the procedure, the action-research process of reflection on what they were doing, and what they were learning, helped the participants to realise how they were gaining in terms of knowledge and skills, and to entrench their slowly building levels of self-efficacy.

Limitations of the research

Although I believe the participatory methods used in this study helped to overcome some of the challenges of peer education highlighted in literature by reducing the didactic tendency of peer educators, keeping the focus on the social and structural aspects of gender, and flattening power relations to avoid 'take over' by the teachers and equalise gender dynamics among the participants (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002), I also acknowledge that the social and cultural environment in which the youth live may constrain communication of their message to the wider community. Peer education is only one way of addressing gender inequality, and must be accompanied by wider social, structural changes to have a lasting effect.

So, what difference do participatory, arts-based methods make?

The description and discussion of the participatory action-research process above provides an answer to my initial research question: How can we engage youth as key actors in educating their peers about HIV prevention, through a gender lens? The visual and arts-based methods allowed the participants to be the main decision-makers on what data were generated, and how this material should be used to educate the wider community. In contrast to teachers telling learners about gender inequalities, the participatory methods adopted created space for the participants to deconstruct and to reconstruct their ideas on what gender injustice was, what implications it held for their lives, and how they could contribute to making positive change.

The research design supported them when taking action to influence their community; and in the process, they themselves developed a higher degree of self-efficacy that enabled them to be more confident and motivated to be peer educators. By first interrogating their own beliefs and behaviour around gender, positive change at the individual level could be encouraged. This better placed them to be able to influence gender norms in their spheres of influence. I would conclude that the evidence presented in this article points to the participatory, reflective and action- oriented nature of the research process should be the main reason for the development of their ability to make a difference as peer educators.

The rich description of the process given in this article should hopefully enable other interested researchers and teachers to use participatory arts-based methods as a basis for their own interventions with youth. Further research into such methods is needed to build up a body of evidence on the effectiveness of using participatory methods to contribute to changing the way youth perceive and embody gender norms.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge the generous funding provided by HIVOS for this project and thank colleagues who acted as research associates in the project, and were involved at one time or another: Prof N de Lange, Dr M Khau, and Ms C Mazomba.

References

Alderman H, Hoddinott J & Kinsey B 2006. Long-term consequences of early childhood malnutrition. Oxford Economic Papers, 58:450-474. [ Links ]

Bandura A 2002. Socio cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology, 51:269-290. [ Links ]

Bandura A 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W.H. Freeman & Company. [ Links ]

Baum F, MacDougall C & Smith D 2006. Participatory Action Research. Journal of Epidemiology Community Health, 60:854-857. [ Links ]

Baxen J, Wood L & Austin P 2011. Reconsidering and repositioning HIV and AIDS within teacher education. Africa Insight, 40:1-10. [ Links ]

Belden KA & Squires KE 2008. HIV infection in women: do sex and gender matter? Current Infectious Disease Report, 10:423-431. [ Links ]

Bhana D 2007. Childhood sexuality and rights in the context of HIV/AIDS. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 9:309-324. [ Links ]

Bruce J 2007. Girls left behind: Redirecting HIV interventions towards the most vulnerable. Brief 23, August. New York: Population Council. Available at www.advocate.com/news. Accessed 2 April 2012. [ Links ]

Campbell C & MacPhail C 2002. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: participatory HIV prevention. Social Science and Medicine, 55:331-345. [ Links ]

Carr W & Kemmis S 2002. Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. London: RoutledgeFarmer. [ Links ]

Chong J 2005. Biological and Social Construction of Gender Differences and Similarities: A Psychological Perspective. The Review of Communication, 5:269-271. [ Links ]

Creswell J 2005. Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (2nd ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Pearson Education. [ Links ]

De Lange N, Mitchell C, Moletsane R & Stuart J 2012. Youth as knowledge producers in community-based video in the age of AIDS [A sidebar]. In S Poyntz and M Hoechsmann (eds). Teaching and Learning the Media: From Media Literacy 1.0 to Media Literacy 2.0. Malden, MA: Wiley- Blackwell. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2010. Draft Integrated Strategic Plan on HIV and AIDS. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2011. Draft Curriculum Assessment and Policy Statements. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education Available at http://curriculum-dev.wcape.school.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=372&Itemid=1191. Accessed 10 April 2012. [ Links ]

Deutsch FM 2007. Undoing gender. Gender and Society, 21:106-127. [ Links ]

Ertiirk Y 2005. "Integration of the Human Rights of Women and the Gender Perspective: Violence against Women ". Intersections of violence against women and HIV/AIDS. Report of the Special Reporter on Violence against Women, its Causes and Consequences. Geneva: United Nations, Commission on Human Rights. [ Links ]

Fargas-Malet M, McSherry D, Larkin E & Robinson C 2010. Research with children: methodological issues and innovative techniques. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 8:175-192. [ Links ]

Fox AM 2010. The social determinants of HIV serostatus in sub-Saharan Africa: an inverse relationship between poverty and HIV. Public Health Reports, Supplement 125:16-24. [ Links ]

Gilbert L & Walker L 2002. Treading the path of least resistance: HIV/AIDS and social inequalities- a South African case study. Social Science and Medicine, 54:1093-1110. [ Links ]

Janse van Rensburg E 2001. "They say size doesn't matter...": criteria for judging the validity of knowledge claims in research. In Research Decisions for the People-Environment-Education Interface. Grahamstown, SA: Rhodes University Education Unit. [ Links ]

Kaufman MR, Shefer T, Crawford M, Simbayi LC & Kalichman SC 2005. Gender attitudes, sexual power, HIV risk: a model for understanding HIV-risk behaviour of South African men. AIDS Care, 20:434-441. [ Links ]

Larkin J, Andrews A & Mitchell C 2006. Guy talk: contesting masculinities in HIV prevention education with Canadian youth. Sex Education, 6:207-221. [ Links ]

Leach F & Mitchel C (Eds) 2006. Combating gender violence in and around schools. London: Trentham Books. [ Links ]

Lichtman M 2012. Qualitative research in education (3rd ed).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Luke N 2005 Confronting the "sugar daddy" stereotype: age and economic asymmetries and risky sexual behavior in urban Kenya. International Family Planning Perspectives, 31:6-14. [ Links ]

McNiff J & Whitehead J 2011. All you need to know about Action Research. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

McTaggart R 2012. Sustainability of Research Practice for Social Justice: A Generation of Politics and Method. In O. Zuber-Skerrit (ed.). Action Research for Sustainable Development in a Turbulent World. Bingley, UK: Emerald. [ Links ]

Minkler M & Wallenstein N (Eds) 2003. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, Stuart J, De Lange N, Moletsane R, Buthelezi T, Larkin J & Flicker S 2010. What difference does this make? Studying Southern African youth as knowledge producers within a new literacy of HIV/AIDS. In C Higgins & B Norton (eds). Language and HIV/AIDS: Say no to AIDS. Salisbury, UK: MPG Books. [ Links ]

Moletsane R, Mitchell C, Smith A & Chisholm L 2008. Methodologies for Mapping a Southern African Girlhood in the Age of Aids. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Morrell R, Epstein D, Unterhalter E, Bhana D & Moletsane R 2009. Towards gender equality: South African schools during the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

Phillips DK & Carr K 2010. Becoming a teacher through action research: process, context, and self-study (2nd ed). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Piggot-Irvine E 2012. Creating Authentic Collaboration: A Central Feature of Effectiveness. In O Zuber-Skerrit (ed). Action Research for sustainable development in a turbulent world. Bingley, UK: Emerald Books. [ Links ]

Pisani E 2008. The wisdom of whores: bureaucrats, brothels, and the business of AIDS. New York: Boydell & Brewer. [ Links ]

Schratz M & Walker R 1995. Research as Social Change: New Opportunities for Qualitative Research. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Schunk D 2008. Learning Theories. An educational perspective (5th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Sherr L, Mueller J & Varrall R 2009. Evidence-based gender findings for children affected by HIV and AIDS - a systematic overview. AIDS Care, 21:83-97. [ Links ]

Skovdal M, Campbell C, Nyamukapa C & Gregson S 2011. When masculinity interferes with women's treatment of HIV infection: A qualitative study about adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Zimbabwe. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 14:29. [ Links ]

Stratton P & Hayes N 1993. A Student's Dictionary of Psychology (2nd ed). London: Edward Arnold. [ Links ]

Stringer E & Beadle R 2012. Tjuluru: Action Research for Community Development. In O Zuber-Skerrit (ed). Action Research for Sustainable Development in a Turbulent World. Bingley, UK: Emerald. [ Links ]

Swartz S 2011. 'Going deep' and 'giving back': strategies for exceeding ethical expectations when researching amongst vulnerable youth. Qualitative Research, 11:47-68. [ Links ]

Theron LC 2009. Educator voices on support needed to cope with the HIV/Aids epidemic. African Journal of Aids Research, 8:231-242. [ Links ]

Triantafyllakos GN, Palaigeorgiou GE & Tsoukalas IA 2008. We! Design: A student-centred participatory methodology for the design of educational applications. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39:125-139. [ Links ]

Wang C 1999. Photo-voice: a Participatory Action-Research Strategy Applied to Women's Health. Journal of Women's Health, 8:185-192. [ Links ]

Wood L 2012. "Every teacher is a researcher!": creating indigenous epistemologies and practices for HIV prevention through values-based action research. Journal for Social Aspects of HIV and AIDS Research Alliance (SAHARA), in press. [ Links ]

Wood L 2009a. Exploring HIV & AIDS literacy among teachers in the Eastern Cape. Journal of Education, 47:127-149. [ Links ]

Wood LA 2009b. What kind of respect is this? Shifting the mindset of teachers regarding cultural perspectives on HIV & AIDS. Action Research, 7:405-422. [ Links ]