Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.32 n.3 Pretoria Jan. 2012

ARTICLES

An investigation of strategies for integrated learning experiences and instruction in the teaching of creative art subjects

Yolisa Nompula

School of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa nompula@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This study investigated the integrating possibilities within each creative arts subject. The objective was to optimize the limited teaching time, generally allocated to each art subject in schools, by developing a pedagogical strategy for its successful implementation. While the study was limited to South African schools, the results have global relevance and significance in the ongoing global trendsetting and discourse on arts education. In South Africa the previous National Curriculum Statement (NCS, 2002) integrated music, dance, drama and visual arts where possible, while the new Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS, 2011) offers two elective art subjects in the senior phase (Grades 7-9), each taught separately an hour per week during school hours and one hour per week after school, thereby attempting to extend the teaching time. This qualitative enquiry used documentary analyses, teacher interviews, and student group discussions for the collection of data. Pre-determined and emergent codes based on grounded theory showed that it is possible to integrate theory with practice within one art subject by teaching theoretical work in the context of practical work, thus optimizing the limited time allocated to arts and culture education in school timetables.

Keywords: arts; arts and culture; arts integration; creative arts; education; performing arts

Introduction

Based on the results of an investigation derived from extensive interviews with educators from all nine provinces in South Africa, the Review Committee of the National Curriculum Statement (NCS) (Motshekga, 2009) identified two important areas for the effective implementation of curricula, namely, pedagogy and content, which form the pre-selected categories on which this study focused. Based on the global trend of arts integration, as expanded upon below, the terms pedagogy and content are used in this study to include the aspect of integration, incorporating theoretical and practical conceptual learning. Since the new Creative Arts Policy Statement (henceforth CAPS, 2011) already takes into consideration the difficulty of practically implementing the integration of the four art subjects by separating the teaching of them, this study focused on the integration of practice and theory in arts education. The research aims to assist arts educators, arts subject advisors and university Education faculties with information on the realities of arts experiences in South African schools and to strategize new teaching approaches for the successful implementation of the arts programme.

Theoretical framework

The section is set out according to the two pre-selected codes on which the study was based, pedagogy and content, as mentioned in the Introduction.

Pedagogy

Pedagogy can be described as principles and method of instruction. One of the main causes for the crises that are experienced with post-democratic education in South Africa is the bridge from a content-based paradigm to an outcomes-based one, the former paradigm having used a hidden political curriculum that engendered a system of cultural hierarchy based on race. To move away from a teacher-centred pedagogy, Camp and Oesterreich (2010) recommend an authentic, learner-centred, integrated multicultural pedagogy that uses tools such as inquiry and constructivism as approaches for powerful learning experiences. In this case the teacher engages the learners in inquiry based on research of abstract concepts they learn in the classroom, in order to compare and construct personal meaning that relates to their own social background, thus guiding them to an understanding of the complexity of human experience. Cole (2009) recommends group activities that pair learners to complement each other's strengths, and the use of 'three knows' to introduce new concepts: What I am sure I know, What I think I know, and What I want to know.

Integrated arts education is a world-wide trend that has been widely promoted by many educators for its consolidative qualities that incorporate general literacy skills. It is important for the development of literacy skills, the latter term used by Wagner, Venezky and Street (1999) to describe expertise in various content areas, pointing out that the term is to some extent a function of culture. In many preschool classrooms arts are valued as precursors to written language, aids in promoting oral language, and bridges to developing cognition, creativity, social interactions, and motor control (Bowman, Donovan & Burns, 2001). Pearson (1998), who deems the arts cognitive in character, argues that the arts serve as entryways to the processes of thinking and learning, saying that arts engagement involves many cognitive areas, such as analytical thinking, problem posing, and verbal reasoning.

Gradle (2009) proposes the use of artistic cognition, defining it as the ability to bring an artwork into being through solving problems, organizing structures into wholes, establishing a figure-ground relationship and therein create unity. Recognizing cognitive styles as individual differences in grasping concepts, Hesham and Wing (2004) maintain that cognitive styles, achievement, motivation and prior knowledge may have an effect on students' learning. This means that the content knowledge taught to learners may not always have the desired outcomes in learners if adequate consideration is not given to individual learning styles.

Ideally an integrated approach enables a pupil to learn concepts from several cognitive and experiential points of view. Pupils thus become proficient in joining discriminative and inferential modes of learning (Gordon, 1997). Codenza (2005) is of the view that the expected outcome of an integrated approach is that the pupils learn to infer or generalize from information learned in one subject area, to gain understanding of the other subject area, and vice versa. Cole (2009), Roulston (2006) and Hargreaves and Marshall (2003) recommend a learning programme that also includes motivational material, that is, material based on student interests and learning styles, then design flexibly grouped activities that target interests and specific learning styles.

An old pedagogy that is still relevant today, but needs special mentioning owing to its importance in arts education, is the focus on experiential learning; this teaching method already became popular some decades ago, but due to the global trend of public schools often using non-specialist art teachers, a reiteration of its practical implementation is necessary. Kolb (1984) advocates an experiential learning cycle based on concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization and active experimentation that may be provided through a range of pedagogical strategies, including didactic teaching, simulations, informal learning through small and large group discussions, reflective practice exercises and activities, as well as negotiating an internship within the creative and performing arts industry. In contrast, Gradle (2009), promoting the Shaefer-Simmern art teaching method, prescribes the Socratic questioning method to challenge, lead and encourage self-discovery and self-evaluation, keeping direct comments and suggestions to a minimum, in order to lead students to create and evaluate their own art, which has meaning in their daily life. Comparisons with historical works would be done afterwards to enrich insight and not dictate.

Another global trend in arts education is the accommodation of web-facilitated learning. To make arts learning more contemporary and effective for learners, educators should employ the latest technologies in the classroom. Delacruz (2009) feels that electronic media and the Internet are widely recognized as the tools and vehicles through which local, regional and global institutional contemporary activities and effective transformation take place. Rabkin and Hedberg (2011:53) maintain that an effective arts education which provides for new kinds of arts experiences and participation is more active and holds more personal value for the learner. Such arts education experiences "blur the line between performer and audience, make the beholder a part of the creative process and make artists the animators of community life". Hesham and Wing (2004) contend that web-based learning is more effective in reaching all types of students, and reducing differences in the academic performance among different student learning styles. Their research confirms that it accommodates a wider range of learning styles, recommending supplementation of web-based learning with a variety of instructional strategies, such as presenting graphic organizers of content, concept maps, and salient navigation cues to help slower learners.

In terms of pedagogy as mentioned by the various authors above, it can thus be suggested that theory and practice in arts education can be integrated by focusing on practical work. This means that learners should be engaged in practical activities even when dealing with theoretical concepts. These include learner research of abstract concepts, group activities, facilitation of learner understanding through individual creation of art works or performances, web-based learning, as well as the use of motivational material to ignite learner motivation and facilitate practical learning.

Content

Content in this study may be defined as the outcomes or learning experiences of the arts programme. The implementation of content or effective learning experiences in the arts in each grade depends on several factors. Frick's (2008) research into practices at South African schools indicates that the actual interpretation and implementation of curricula differ from school to school as a result of teacher ability and aptitude, the access schools have to resources, and the academic background of learners. Currently in South Africa the Curriculum and Assessment Statement (CAPS) (Department of Education, 2011) offers schools the choice of two arts subjects in Grades 7-9, based on physical and human resources, to help focus and prioritize learning for those who elect to continue with the arts in Grades 10-12 (the Further Education and Training band). This may alleviate the workload of both learners and teachers, but many schools may only offer a narrow choice of art subj ects and not the learners' particular preferences. Learners may therefore be compelled to take arts subjects based on what their school is able to offer in terms of human and physical resources. As such, much potential talent may go wasted.

Teacher competency and aptitude are important in implementing arts education successfully. Faculties of Education that offer pre-service training to prospective teachers of the creative and performing arts should facilitate inclusion of contemporary global trends and changes in national policy. Fullan (1982) recommends that pre- and in-service work with teachers should include several sessions based on theory, demonstration, practice and feedback, with appropriate intervals between follow-up sessions. He stressed the importance of both formal and informal interchanges between teachers and arts professionals, and that professional development should be considered a continuous undertaking.

The successful learning and appreciation of the arts are important for long-term impact on future generations. In a periodic public survey (1982-2010) conducted in the United States of America, Rabkin and Hedberg (2011) found that the decline in arts education in schools had direct impact on the appreciation of classical music and participation in the arts industry in adulthood, resulting in poor concert and arts exhibition attendance and a decline in jobs in the arts and music industry.

While arts education is a time-consuming, specialized teaching subject, the reality in the public school system is that principals generally require educators to teach two subject areas or one subject to several grades, in order to meet the minimum teaching hours required for full-time employment. In arts education, the teaching of Music alone involves Music Literacy (Theory of Music), Music Listening (History of Music) and, Performing and Creating Music. With the two hours per week generally allocated to arts education during official school hours, this brings the effective implementation of each art subject into question. Upitis (2005:6) aptly said that it is "perennial and universal lament among artists, artist-teachers, and teachers alike, that there is not enough time to plan arts encounters for students". While the new South African CAPS: Creative Arts, senior phase (2011:7), extends teaching time to an extra two hours after school, this after-school teaching robs teachers of time usually spent in preparing lessons, marking assignments, setting tests and catching up on other administrative work.

A general, global occurrence in arts education is that many public schools, which lack art specialists, allow the teaching of the arts among volunteer educators who are not trained or skilled to teach art subjects. Garvis (2010), whose student teachers experienced and discovered this to be the case in some of the schools in Australia where they did their teaching practice, found that the use of generalist teachers for a specialized subject reduces the perceived importance and educational impact on learners. Shulman coined the term "pedagogical content knowledge" in 1968 to describe the idea that pedagogical practice is uniquely connected to specific content areas, and that the nature of subject content combined with student learning needs determines and shapes the pedagogy teachers must use. An educator not trained in an art subject lacks the content knowledge and skills needed to effectively teach one of these specialized subject areas.

The above paragraphs suggest that the integration of the content of arts subjects is dependent on teacher skills and aptitude. While the CAPS curriculum provides the content of the Creative Arts syllabi, it is up to the resourcefulness of the teacher to optimize the limited time of a specialized, time-consuming practical subject by linking and integrating the abstract concepts of the syllabus with the practical learning experiences.

Method

The research was a qualitative study that was guided by the research question: "How can art teachers integrate the Creative Arts in order to optimize the limited time allocated to the teaching of these practical subjects?"

The research was limited to Grades 7-9 in 20 former Model C schools selected in the KwaZulu-Natal area of South Africa based on a random convenience sample that focused on the vibrancy of their arts and culture programme, supportive administration and teacher interest. The study was based on grounded theory, a concept introduced by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (1967) to describe observations which lead to patterns, themes or common categories, allowing latitude for discovering the unexpected. Instruments used in the collection of data included documentary analyses, teacher interviews and learner group discussions based on semi-structured, open-ended questions.

The participants were Zulu and English mother-tongue speakers, comprising altogether 36 Creative Arts teachers and 1,052 learners. Group discussions with learners were conducted during their Creative Arts classes, producing data of 20 periods, each 40 minutes long. Teacher interviews followed in the privacy and seclusion of an office or empty classroom and consisted of 36 sessions of data, each 30 minutes long. The learner and teacher sessions were audio-recorded with a dictaphone, the learner sessions being supplemented with note-taking. Most schools employed more than one Creative Arts teacher. At some schools it was therefore possible to interview two or three teachers, while at others only one teacher was available for an interview.

Design

This phenomenological study used participant observation, interviews and group discussions to collect field data. Data analyses, used as a precursor to fieldwork, involved the reading and analysis of national policy documents and relevant literature to identify the most current and relevant areas of the research problem. Through this analysis two concepts, Pedagogy and Content, were selected as predetermined codes for this study and served as a guide around which the fieldwork was structured.

In addition, emergent codes were derived from the data obtained from participant observation. A third main code, Effective Learning Environment, was consequently added, as well as sub-codes under both predetermined and emergent main codes. Sub-codes that emerged from the field data include Pedagogy Project Method, Discussion Method and Discovery Method; Content Theoretical Work and Practical Work; and Effective Learning Environment Teachers' Concerns and Learners' Concerns.

Participant observation allowed the researcher to be actively engaged with the participants in the educational environment with which they were familiar. Classroom discussions involved the researcher replacing the arts and culture teacher by interacting with the learners, asking them questions and inviting them to freely participate, while walking among them and holding the dictaphone to record all responses. Interviews with teachers took place after classroom discussions in the form of informal conversations in a relaxed and non-threatening atmosphere. In the waiting period between classroom discussions and teacher interviews, brief field notes were made to supplement recordings of classroom discussions.

Ethical considerations

In compliance with research ethical policy, all precautions were taken in advance of the study to protect the autonomy and anonymity of respondents. Letters for permission to conduct the research and informed consent forms were sent and subsequently received from the provincial Department of Education, selected school principals, Creative Arts teachers, learners and their parents or legal guardians. Respondents were informed that they were free to withdraw from the research at any time without any undesirable consequences. In addition, they were given sample questions in advance to give them an idea of what to expect to be asked, in order to consider their participation.

Results

Documentary analyses revealed that the greatest potential for effective optimization of the limited teaching time available for the Creative Arts in schools were to integrate Creative Arts content, and to enhance the pedagogical methods that teachers use in Creative Arts instruction. These two themes formed the basis for the fieldwork research. The data obtained from interviews and group discussions are presented below in terms of the two pre-determined categories of Pedagogy and Content, integration forming an integral part of each. The teaching methods under pedagogy arising from the binary data include Project Method, Discussion Method and Discovery Method. A third category emerged from the binary data, namely Effective Learning Environment, with its own important considerations. Results are presented in terms of percentage.

Project method

While all 36 teachers (100%) revealed that they used group work in teaching Creative Arts projects, they felt that learners did not particularly like this method of learning. Twelve teachers (33%) recommended the delegation of work in pairs or individually in research activities, and groups of four or more in practical work. Some learners liked group work, while others preferred to work on their own. Of the 1,052 learners who participated in the research study, 551 (52%) said they learn faster when working in groups ranging from no more than 2-4, while 501 (48%) said they preferred to work alone. Common reasons given among learners for preferring group work included that they could share ideas, teach and help each other, give each other advice and suggestions, and that it helped them to communicate and team with classmates and friends. Common reasons given for working individually were that others were slow and kept them behind, some laughed at them, some were lazy and slow and did not contribute, they talked too much and distracted their attention from the task at hand, and they often conflicted and were unable to agree on things, while some were not serious and wasted their time.

Discussion method

All 36 (100%) teachers discouraged the use of teacher-centred methods such as the 'Telling' method where the teacher appears dominant, intolerant and strict, instead recommending the 'Discussion' method to allow open communication. Teachers further recommended refraining from trying to get learners to talk in class about sensitive issues that personally affect them, such as HIV/AIDS, and from trying to get individual students to perform songs or dances in front of the class. Instead 26 (72%) teachers suggested freedom of expression, and in practical work, a move away from established notions of perfection by allowing for improvisation and uniqueness. Three teachers (8%) used motivational speeches in an attempt to get learners to feel free to communicate and express themselves, while two others (6%) felt that relating new knowledge to contemporary life helped to encourage learners to communicate freely, relating their own experiences.

Three teachers (8%) used peer-teaching to reinforce learning or exchange teaching among different Creative Arts specialists to maintain interest. The latter experiences served as opportunities for opening channels of communication and freedom of expression, both verbally and creatively. Praise and commendation for achievements were not only used as a source of motivation, but also to help open discussion by two (6%) teachers.

Learners confirmed that Creative Arts educators were less teacher-centred than other educators. Regarding motivation, an overwhelming majority of 797 (76%) learners said it was the teacher's enthusiasm and passion for the arts that inspired and gave them freedom of expression, while 203 learners (19%) said it was their celebrity role models such as singers, movie or television actors/actresses, poets, dancers, photographers and artists; and 52 (5%) said that their parents motivated them.

Discovery method

The 'Discovery method' developed as a separate theme under learner group discussions. Educational DVDs, excursions and computer-assisted learning all facilitate learning by discovery.

While most schools had a television and DVD player which was kept centrally and used on request, only three had television sets inside their classrooms. Most teachers seldom showed learners DVDs, but the large majority of learners felt that educational DVDs would be effective tools of learning. In response to the question of how educational DVDs would help them to learn about the arts, a majority of 882 (84%) learners said that DVDs would help them to make the learning experience more vivid and memorable in that they would be able to hear and see what is happening, and it would demonstrate how to do carry out instructions, while the remaining minority of 170 (16%) said that DVDs would take the focus away from the learning objective and instead serve as entertainment. Among the 36 teachers interviewed only 3 (8%) mentioned that they showed educational DVDs to learners to serve as sources of inspiration to them.

Excursions were identified as field trips or visits to places to further education such as symphony concerts, theatre, plays, recording or art studios, among others. All 1,052 (100%) learners felt that excursions gave them practical examples to learn from, exposed them to new experiences, excited them and made them remember everything they saw, and they got firsthand knowledge and information from the professionals in the field who ho sted them. Learners also identified what arts or cultural events they would most likely attend with their parents or friends: 360 (34%) attend church, 236 (23%) go to the cinema, 226 (22%) attend sports matches, 89 (8%) attend school entertainment, 51 (5%) attend Gospel shows, 28 (3%) attend poetry readings, 16 (2%) attend fashion shows, 14 (1%) attend theatre shows, 12 (1%) attend art exhibitions, 12 (1%) attend photography exhibitions. This shows that few learners receive educational exposure to live musical performances, visual art exhibitions, recording studios or cultural places of interest, either at home or school. While all learners extolled the effectiveness of excursions, no teachers mentioned that they took learners on excursions to experience first-hand the practices of the arts industry.

Despite the observation that the majority of learners came from less favourable economic backgrounds, a majority of 987 (94%) participants reported having computers at home. The remaining 65 (6%) learners had access to computers through friends. All learners felt that computers were useful for research on arts and culture as well as searching for educational institutions to pursue further studies; viewing educational videos; and typing assignments, plays and poetry. Specific software was also identified as beneficial: music software that can help them to write songs and other musical compositions, cut soundtracks or make their own recordings; graphic design software that can help them to create their own pictures; software that teaches them how to play the piano, using a keyboard connected to the computer; architectural design software; and software to create their own animated movies. Of the 36 teachers interviewed, only 6 (17%) mentioned that they recommended learners use their computers at home for research projects and typing assignments, complaining about plagiarism when learners use computers for research.

Content

The themes emerging under the content of an integrated arts programme included Theoretical Work and Practical Work.

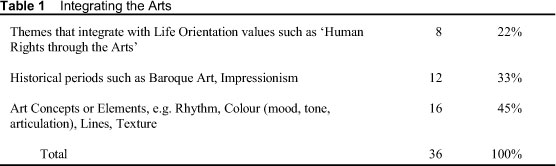

The 36 teachers interviewed advanced three suggestions for integrating areas of arts study, as seen in Table 1. Despite these suggestions, most teachers did not seem to apply them practically or, alternatively, seemed not to know how to sustain such integration for an entire year.

Of the 36 teachers interviewed, 22 (61%) music specialists admitted that Music Theory was difficult to integrate, some of them ignoring their own suggestions of using common concepts such as rhythm (time signatures, note values), mood (key signatures), texture (harmony, counterpoint), and colour (ornamentation, instrumentation, articulation) to integrate areas of arts learning. Similarly, the other teachers also seemed to contradict themselves: 14 (39%) Fine Arts specialists mentioning that it was difficult to integrate Fine Art, two (6%) drama specialists bringing up oral presentations and two (6%) referring to poetry reading as units to be taught separately. This seems to give substance to the observation that teachers did not know how to integrate the different areas of arts and culture learning, despite having theoretical ideas of how to do it.

All learners felt that theoretical work should be integrated with practical work and not be taught separately. When probed about the use of practical examples to integrate theoretical concepts, asking what type of exposure their parents would not approve of, the responses were as follows: 238 (24%) said movies with an 'S' (sex) rating or any pornographic content, 182 (17%) said hip hop and rap music because of the strong words in the lyrics, 171 (16%) said music videos in which singers drink alcohol, smoke or use drugs, 153 (15%) said dancing at disco clubs, 128 (12%) said movies which have lots of violence, 112 (11%) learners said their parents prohibited them from visiting clubs and taverns, 42 (4%) said performing or seeing exotic dancing, and six (1%) said rock music because it is noisy.

All 36 teachers interviewed admitted that their pupils find theoretical work and tasks difficult, saying that they enjoyed practical work more. All teachers (100%) recommended the use of musicals and plays that integrate music, dance, drama and visual arts (props and costumes). They also suggested introducing extra-mural activities such as musical ensembles and visual arts and poetry societies to give learners free creative reign and opportunity to put into practice what they learn.

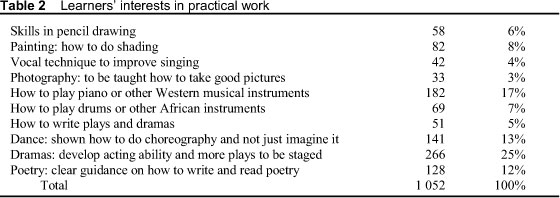

Confirming their love for practical engagement, learners came up with their own areas of interest in practical work (Table 2).

In an effort to determine whether learners continued their supposed love for arts engagement after school hours, they were asked if they received private tuition in any musical instrument or other art form. However, only six (1%) of the 1,052 reported receiving piano lessons, others considering their singing in a church or school choir, playing in a sports team and membership with poetry or drama societies as some form of arts training.

Effective learning environment

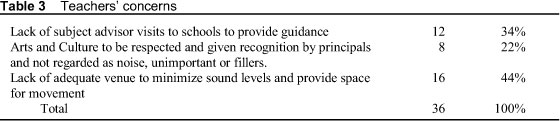

When both teachers and learners were asked to make comments on anything that they were not asked, the lack of an adequate learning environment emerged as a theme.

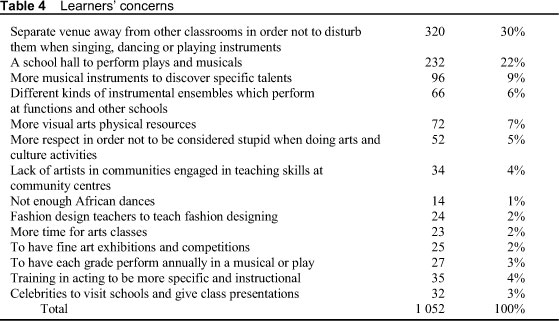

Common responses among teachers appear in the Table 3, while the responses of learners are presented in Table 4.

Common concerns among both teachers and learners are the lack of an appropriate teaching venue separate from other classrooms, and the need for respect for arts education as a viable learning area.

Discussion

The data were analysed in terms of the commonalities and differences of their attributes. They reveal that integration between theoretical and practical work within one art subj ect is possible, while integration among the four different art subjects is difficult to achieve, except when staging school concerts in which plays or musicals are featured.

A common teaching method for the integration of an art subject, whose benefits seemed appreciated by all teachers and the majority of learners, was the Discussion method. The teacher's accommodative personality and passion for the subject seemed to allow for flexibility in creativity and an atmosphere conducive to freedom of expression. Another learner-centred method, apparently practised by most arts teachers, was the Project Method. More or less one in every two learners welcomed group work as a method of learning. However, slow learners seemed to benefit more than fast learners, citing that their brighter peers simplified and facilitated better understanding. Arts teachers were ostensibly aware of the dissatisfaction with the use of group work among fast learners and compromised by using the Project method essentially for practical work such as ensemble and dance performances or projects where collective effort is an integral part of creative production.

While teachers ostensibly stuck to the above traditional learner-centred methods, learners, on the other hand, preferred the modern, contemporary ways of education that featured learning by discovery. Learners favoured educational excursions, DVDs and computer software and websites that made learning more enjoyable and memorable, realizing that education was integrated with real life and that teachers were not the authority of subject matter.

With the teachers serving as facilitators of the learning process, the content of education in the arts gravitated towards practical work, a feature recognized and accommodated in the new South African CAPS: Creative Arts (2011) curriculum.

A strong focus that emerged from the data was the preference for practical work for all art subjects. With learners, the recipients of the education process, complaining about not receiving enough practical education, and teachers revealing that learners are more motivated and learn better when engaging in practical work, learning experiences in art subjects should focus on practical work.

Time may therefore be optimised by integrating theoretical concepts with practical work within the same subject area, instead of teaching them separately. This in essence implies experiential learning at all times, as apposed to abstract learning of theoretical concepts in one lesson, while another lesson focuses on an isolated creative activity in which learners fail to make the link between theory and practice. Learners also complained about not being given enough practical guidance or demonstration when asked to create or perform. This could be in cases where teachers themselves lacked experience or satisfactory teaching skills.

While CAPS (2011) has already observed teacher complaints of the difficulty in integrating music, visual arts, dance and drama under Arts and Culture, the present data obtained from teachers showed that teachers positively responded to suggestions for integration of these four art subjects without having themselves implemented such suggestions or knowing how to sustain such integration for a whole year.

Learners said that integration of the four art subjects happens only once a year and not as often as they would like. This sole opportunity is the performance of plays and musicals as a school production in public concerts. This suggests that annual or semester plays or musicals could be used to optimize creative learner output where assessment of the individual subject is done in one collaborative performance, while simultaneously giving all learners the opportunity to participate through their own medium of creative expression.

If such plays, in which the art subjects collaborate, form part of an end-of-year assessment, it would present more scope for learner creativity and give all learners who study an art subject the opportunity to experience public exposure. This would help the respective art teachers to save time on adjudicating a series of time-consuming individual examinations and instead in one sitting assess all art students simultaneously.

While the researcher was conducting the present research at one school, a drama teacher presented her with a copy of a complete school play written by one of the learners. At other schools, learners enthusiastically read her the poems they had written, showed her the murals they had painted on a school wall, performed her the choreography they had put together on their own or sang her the songs they had written themselves.

These creative efforts of learners show that they are capable of impressive work that needs to be publicly recognized and validated for support and encouragement. One suggestion would be an annual school competition, done in collaboration with professional artists, in which learners write creative works in all streams of art expression, with the main prize in each art category being professional tuition for a limited period of time. This would not only motivate learners to be more creative, but it would also help teachers to integrate theory with practice by linking school learning with real life in society.

The data also reveal that most art educators teach art theoretically, due to the lack of adequate art materials and in order to compromise on disrupting other neighbouring classes, as a result of the lack of an appropriate venue. Without the necessary art resources, it would be practically impossible to integrate theory with practice by focussing on practical work, hence an effective learning environment becomes necessary.

Despite the recommendation in South African policy (CAPS: Creative Arts, 2011) for certain human and physical resources to be available for the offering of certain arts choices, the reality is that most schools lacked such resources and thus could only offer a narrow, basic education in the arts. Two particular subjects lacking in most schools that some learners were particularly interested in were fashion designing and poetry writing, the latter considered part of the Creative Arts and not English.

Many schools did not have the necessary educational environment to provide opportunity for learners to develop their potential artistic talents. The lack of a large venue situated apart from the cluster of classrooms was the main complaint by most schools. With the lack of appreciation for the arts manifesting among principals and teachers of other subjects, partly due to their complaints about sound levels as a result of musical and dance performances, learners were apt to lose their self-esteem and assertiveness in both appreciating and performing artworks. This diminished the value of the whole educational experience in the arts, rendering it an entertainment and leisure activity, rather than an important contribution to the holistic development of the learner.

With the latest national Creative Arts curriculum (CAPS, 2011) taking into consideration the past deficits experienced at schools in arts education, the current school reality showed a picture far from ready to meet the welcome changes and new challenges.

Conclusions and recommendations

The research results revealed that the limited teaching time in each art subject could be optimized by integrating theory with practice through focus on creative output and the acquisition of practical skills. Wasting a lot of time in teaching practical concepts theoretically, with little time left for the actual practical implementation of those concepts in the creation of artworks or performances, is something that can thus be avoided.

While the four art subject areas are taught separately, the collaboration among the four art subjects in semester or annual collective examinations through combined performances in plays or musicals could further add to the saving of time spent on separate individual assessments.

To further optimize the limited teaching time and to focus teaching on practical work, the following should be considered:

- Teachers could introduce clubs, musical ensembles or societies for each art subject that could be run by the learners themselves under the supervision of an art teacher, in order to give learners more scope for development and an avenue for creative output.

- To accommodate integration of theoretical concepts with practical output within one subject area, learner-centred teaching methods should be employed to encourage creativity and active participation, such as the Discussion, Project and Discovery Methods.

- The use of contemporary audio-visual aids that not only facilitate discovery learning, but also facilitate different learning styles, such as educational DVDs, educational excursions and computer-assisted learning, providing alternative or supplementary ways of focusing on practical work.

- Teacher personality and magnetism that allow for freedom of expression and fun, toning down the autocratic attitudes of intolerance, strictness and inapproachability.

- The use of praise and commendation, where appropriate, to motivate and maintain learner interest, thereby making learning more effective.

- Teacher participation in exchange teaching, not only within the same school, but also across schools, to provide for skills in certain arts areas that are lacking in a particular school, in order to cater for learners' interests and talents.

In the context of the study, it is suggested that future research focuses on the development of an arts learning programme for one particular grade, implementing the integration of theory and practice of one particular art subject.

References

Bowman B, Donovan M & Burns M (eds) 2001. Eager to learn: Educating our pre-schoolers. Washington DC: National Academy Press. [ Links ]

Camp EM & Oesterreich A 2010. 'Uncommon teaching in commonsense times: A case study of a critical multicultural educator & the academic success of diverse student populations'. Multicultural Education, 22. Available at http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Uncommon+teachmg+m+ commonsense+times%3a+a+case+study+of+a+critical...-a0227945947. Accessed 15 July 2011. [ Links ]

Codenza G 2005. 'Implications for music educators of an interdisciplinary curriculum'. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 6:9. [ Links ]

Cole S 2009. Accommodations and instructional strategies that can help students. Vermont: Department of Education. Available at essconsultants@state.vt.us. Accessed 4 July 2011. [ Links ]

Delacruz EM 2009. 'From bricks and mortar to the public sphere in cyberspace: Creating a Culture of Caring on the Digital Global Commons'. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 10:5. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2002. Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools): Arts and Culture. Pretoria: Department of Education. Available at http://education.pwv.gov.za. Accessed 3 June 2011. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2011. National Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS): Creative Arts, Senior Phase. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

Frick BL 2008. The profile of Stellenbosch University first-year student: Present andfuture trends (Preliminary research report draft 4). Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University Centre for Teaching and Learning. [ Links ]

Fullan M 1982. The meaning of educational change. Toronto: OISE Press. [ Links ]

Garvis S 2010. 'Supporting novice teachers of the arts'. International Journal of Education and the Arts, 11(8). Available at http://www.ijea.org/. Accessed 5 July 2011. [ Links ]

Glaser B & Anselm S 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Aldine, Chicago. [ Links ]

Gordon EE 1997. Learning sequences in music. Chicago: GIA Publications. [ Links ]

Gradle SA 2009. 'Another look at holistic art education: Exploring the legacy of Shaefer-Simmern H'. International Journal of Education and the Arts, 10:1. [ Links ]

Hargreaves DJ & Marshall NA 2003. 'Developing identities in music education'. Music Education Research, 5:263-273. [ Links ]

Hesham A & Wing A 2004. 'Exploration of instructional strategies and individual difference within the context of web-based learning'. International Education Journal, 4:4. [ Links ]

Kolb D 1984. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Motshekga A 2009. Final Report of the Task Team for the Review of the Implementation of the National Curriculum Statement. Pretoria: Department of Education. Available at http://education.pwv.gov.za. Accessed 3 June 2011. [ Links ]

Pearson B 1998. Busting multiple intelligences myths. Available at http://www.barbarapearson.com/philosophy.html. Accessed 15 July 2011. [ Links ]

Rabkin N & Hedberg EC 2011. Arts education in America: What the declines means for arts participation. University of Chicago: National Endowment for the Arts. Available at www.arts.gov. Accessed 25 June 2011. [ Links ]

Roulston K 2006. Qualitative investigation of young children's music preferences. International Journal of Education and the Arts, 7:9. [ Links ]

Upitis R 2005. Experiences of artists and artist-teachers involved in teacher professional development programs. International Journal of Education and the Arts, 6:8. [ Links ]

Wagner D, Venezky R & Street B (eds) 1999. Literacy: An international handbook. Boulder: Westview Press. [ Links ]