Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.32 no.1 Pretoria ene. 2012

The influence of school culture and school climate on violence in schools of the Eastern Cape Province

Kalie BarnesI; Susette BrynardII; Corene de WetII

IEastern Cape Department of Education, Queenstown

IISchool of Education Studies, Faculty of Education, University of the Free State dewetnc@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article reports on research undertaken about the influence of school culture and school climate on violence at schools in the Eastern Cape. An adapted California School Climate and Survey - Short Form (CSCSS-SF), which was used as the data-collection instrument, was completed by 900 Grade 10 to 12 learners. With the assistance of Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient, it was found that the better the school culture and school climate are at a school, the lower the levels of school violence. On the other hand, a lack of school safety contributed to learners experiencing higher levels of violence at schools. The results of hierarchy regression analyses indicated that school culture and school climate can be used to explain a significant percentage of variance in school violence. The f2 values indicate that, with the exception of two aspects of the variance physical and verbal harassment, the results did not have any practical value. The article concludes with a few suggestions on how the results can be used to address school violence.

Keywords: CSCSS-SF; school climate; school culture; school violence

Introduction

Violence and crime in South African schools are a critical problem (Le Roux & Mokhele, 2011). According to the South African Institute for Race Relations, South African schools are viewed as the most dangerous in the world. If the problem is not addressed, it could influence the education and training of many learners negatively (Khumalo, 2008). To satisfy the youths' developmental needs regarding safety, respect, authority, love, skills, challenges, independence and existence, it is important that schools should make learners aware of the fact that they are important as human beings and learners, and that they can make a difference in their striving towards a better life (Cohen, McCabe, Michelli & Pickeral, 2008). Cohen et al. (2008) emphasise the responsibility that rests on the shoulders of policy makers and educational leaders to establish a positive school culture and school climate. If they forsake their responsibility, it will violate the learners' right to quality education.

Researchers have found that a positive school culture and a school climate are important dimensions that can be linked to effective risk prevention and the advancement of teaching and learning (Cohen & Pickerall, 2007; Najaka, Gottfredson & Wilson, 2002). Researchers also determined that effective risk-prevention programmes are positively linked to a safe and caring school culture and school climate (Berkowitz & Bier, 2005). According to the above writers, if violence occurs at schools and is not addressed, it can destroy the school culture and school climate, as well as diminish the protective influence of the school. Furthermore, research by Squelch (2001) indicates that since 1994, several documents have been put in place by the National and Provincial Departments of Education in South Africa, which attempt to address violence in schools by establishing a positive school culture and school climate. It therefore appears that researchers and policy makers view a positive school culture and school climate as prerequisites for safe schools.

In the light of the above, and taking into account the needs of schools in their actions against violence, this study is guided by the following primary question: What are the effects of school culture and school climate on violence in the Eastern Cape Province? In the search for an answer to this question, the following research hypothesis was formulated:

• School culture and school climate can be used to explain the significant percentage of variation in school violence.

The aim of this article is, firstly, to establish if there is a correlation between the predictors of school violence (school culture, school climate and safety) and school violence and, secondly, to establish if school culture and school climate can be utilised to explain a significant presentation of the variance in school violence. This will take place against the background of a conceptual framework.

Conceptual framework

School culture and school climate are two separate, but closely related and interactive, dimensions in the functioning of a school (Saufler, 2005). Both school culture and school climate are concepts that can be linked to the atmosphere at a school, but which could influence the circumstances at a school in different ways. Both concepts are important in establishing the quality of the circumstances and the ability to ensure positive learner outcomes. This includes good academic results, as well as non-academic achievements such as well-developed citizens and a positive school environment (Ninan, 2006). As a result of the interactive, extensive and complex elements that construct school culture and school climate, it is necessaryto interrogate the concepts, school culture and school climate.

The concept of school culture is not new. In 1932 Waller (Peterson & Deal, 2002) stated that each school has its own culture with a unique set of customs and history, as well as moral behaviour and relational codes. Gruenert (2008) is of the opinion that a collective set of expectations is developed when a group of people at a school works together for a significant period of time. These expectations then evolve into a set of unwritten rules to which members adapt in order to work well together. In this way, a collective school culture develops and transmits information from one generation to another.

Barth (2002) defines school culture as a complex pattern of norms, attitudes, beliefs, behaviour, values, ceremonies, traditions and myths which is deeply embedded in each aspect of the school. It is an historic legacy of power that is exerted over people's thoughts and their actions. Hinde (2004) views school culture as norms, beliefs, traditions and customs that develop in a school over time. According to him, it is a set of obvious expectations and assumptions which directly influences the activities of the staff and the learners. School culture is therefore not static, but a self-perpetuating cycle which reflects the collective ideas, assumptions and beliefs that reflect each school's own identity and standard of behavioural outcomes.

According to Robbins and Alvy (2009), school culture reflects the aspects that the school community cares about; how they celebrate and what they talk about. It occurs in their daily routine. Theschool culture has an influence on the learners' productivity, professional development and leadership practices and traditions (Robbins & Alvy, 2009). Furthermore, Reames and Spencer (1998) are of the opinion that the internal structures and processes of the school can be a determinant in the efficiency and functioning of a school. For example, collegiality, cooperation, shared decision-making processes, the continuous improvement of educational practices and long-term involvement are seen as ways to enhance the positive culture at a school. Cavanagh and Delhar (2001) agree that factors such as professional development, cooperation and leadership practices contribute to a school of quality. The authors emphasise that the unspoken set of values and aims that contribute to the quality of the daily school routine and motivates all to do their best, impacts on the establishment of a positive school culture. The aim of all the interactive elements of culture is to establish a school environment which promotes teaching and learning.

Although the concept school climate has been studied since1908, teachers and researchers cannot reach consensus on a uniform meaning of the terminology or definitions (Cohen et al., 2008). Depending on the nature of the study, school climate can be regarded as the school environment or as the school learning environment (Johnson & Stevens, 2006). School climate refers to the set of norms and expectations which is presented to the learners (West, 1985); the psycho-social context in which teachers work and teach (Fisher & Fraser, 1991); the morale of the teachers (Brown & Henry, 1992); the level of empowerment for teachers (Short & Rinehardt, 1992); learners' perception of the school's "personality" (Johnson, Johnson & Zimmerman, 1996); the environment for learners as indicated by the incidence of negative leaner behaviour at the school (Bernstein, 1992); or the physical and emotional wellbeing of the school organisation (Freiberg & Stein, 1999). Researchers (Cohen et al., 2008; Johnson & Stevens, 2006) are of the opinion that the following four core dimensions of school life can influence the school climate: safety, teaching and learning, relationships and environment. School climate can therefore be viewed as a combination that represents the involvement of all at the school, or as something that is seen primarily as a function of teachers and learners. Although there are differences in nuances between the concepts school culture and climate, the instrument used in this study does not draw a distinction, and uses the inclusive notion of 'school culture and climate'. The differences in nuances between the two notions will consequently not be discussed further in this article.

Zulu, Urbani and Van der Merwe (2004) see school violence as wilful and illegal violent acts within the school context. The definition of Van der Westhuizen and Maree (2009) links the behavioural patterns of learners, teachers and school administrators with physical violence that result in physical injuries to any person or harm to school property as the objective. School violence is therefore negative behavioural patterns which can harm the school's educational mission. Morrell (2002) and Harber (2008) argue that schools can be violent places. Culturally condoned ethos of masculinity, gender violence, the inculcation of habits of conformity, discipline and morality, the reproduction of inequalities, the intensely competitive examination regimes that lead to high levels of stress and anxiety are some of the ways that schools are a violent experience for learners (cf. Harber, 2002 & 2008; Herr & Anderson, 2003; Morrell, 2002). Harber (2002) notes that the predominate form of schooling has always been authoritarian, with learners having little control over school curriculum or organisation. He links authoritarianism with racist and/or ethnic violence (in schools). Morrell (2002) writes that teachers whose identities are vested in power and hierarch contribute to violence by being violent, by condoning violence and by supporting a school ethos intolerant of difference and insistent of conformity. Yet, "in many schools the hard teacher or the iron man is held up as the ideal" (Morrell, 2002:42).

Opposed to this, a safe school is described as a place where the school climate allows learners, teachers, administrators, parents and visitors to communicate with one another in a positive and non-threatening manner (Bucher & Manning, 2005). Dwyer, Osher and Wagner (1998) classify safe schools as schools where strong leadership, parental and community involvement, high levels of learner participation and behavioural codes prevail in order to ensure responsible behaviour. Safe schools are therefore characterised by good discipline, communication, a culture and climate conducive to teaching and learning, good administrative practices and an absence of any levels of crime and violence.

Theoretical framework

Although many traditional and integrated theories regarding violence exist (cf. Bender & Emslie, 2010; Klewin, Tillmann & Weingart, 2003), violence at schools will be reviewed from a bio-ecologic perspective, as adapted by Benbenishty and Astor (2005 & 2008), for the purposes of this study. According to Benbenishty and Astor (2005 & 2008), Bronfenbrenner's bio-ecologic theory creates the notion of violence as the interaction between relevant subsystems. This theory illustrates the interaction between a person's characteristics and environmental variables (social and physical). The environment under discussion could include other people who are involved in the situations (co-learners and teachers), as well as the physical environment (school, class size, school structures). Whilst other bio-ecological models place the individual at the centre (cf. Dunbar-Krige, Pillay & Henning, 2011), Benbenishty and Astor (2005 & 2008) position the school context at the centre.

Empirical study

Research instrument

The California School Climate and Survey - Short Form (CSCSS-SF) was used as the instrument for collecting data. The CSCSS-SF was developed by the Centre for School-Based Youth Development in California. It is a structured questionnaire for learners with the exclusive aim of determining school culture, school climate and school safety. According Barnes (2010), this instrument was also used in international studies undertaken by, amongst others, Morrison, Bates and Smith (1994), Furlong, Sharma and Rhe (2000), and Furlong, Greif, Whipple, Bates and Jimenez (2005), to examine aspects of school culture, school climate and school safety.

Items in the questionnaire dealing with school safety can be divided into subsections, namely, campus disruption, drug abuse and the carrying of weapons. The first of these subsections indicates less serious issues such as theft, fighting and vandalism, while the second subsection represents activities of a more serious nature. The items in these sections are designed to measure the respondents' perceptions of the occurrence of dangerous activities on school grounds. According to a five-point Lickert scale, which varies between not at all to often, respondents are asked how often activities such as drug abuse, vandalism and the carrying of weapons occur on the school premises. A high score in the subscales will indicate a high incidence of campus disruptions and drug abuse, as well as the carrying of weapons.

The section on school culture and school climate measures the respondents' perception regarding the school environment. Respondents had to answer questions regarding safety, respect, support and interpersonal relationships in the school. Items in this section are divided into ten subsections: rules and norms; physical safety; social and emotional assurance; support for learning; social and citizen learning; respect for variety; social support - adults; social support - learners; school union and the physical environment. In this section, a five-point Lickert scale, which varies from I do not agree at all to I completely agree, was also used. A high score in these subscales indicates that respondents experienced school culture and school climate as positive support.

The section on school violence in this questionnaire measured the extent of incidents of school violence. Respondents were asked to indicate their personal experiences during the previous twelve months (not what they perceived) regarding victimisation. Items in this section are divided into three subsections: physical and verbal harassment; weapons and physical attacks; and sexual harassment. The five-point Lickert scale was also used in this section, with answers ranging from not at all to constantly. A high score in the subscale indicates a high level of experience of victimisation.

Construction and background information on the research group

For the compilation of the research group, nonprobability sampling was used. The sampling was also done in a non-random manner; the learners were approached intentionally and according to their availability. Thirty schools in the Eastern Cape Province that teach Grade 10 to Grade 12 were used for the study as a convenience sampling. Because the Eastern Cape Province has 24 school districts and is spread across a vast area, schools from the following districts in the immediate vicinity of the first author were selected: East London (11), Queenstown (13), Lady Frere (5) and King Williamstown District (1). Ten learners from Grades 10, 11 and 12 at each school were asked to complete the questionnaire. Schools were asked to make equal numbers of boys and girls from each grade available. In total, 900 learners participated in the study - 49% boys and 51% girls. With regard to the number of learners from different grades, schools were requested to make the same number of learners available from each grade. The total number of learners from each grade was as follows: Grade 10 - 32,9%, Grade 11 - 33,8% and Grade 12 - 33,3%.

The first author visited each school during the period from 28 April 2010 to 21 May 2010 and was personally responsible for the administration and taking down of the tests. Therefore, he could ensure that respondents understood the outline of the questionnaire; he could deal with any ambiguities related to questions on the questionnaires; and he could ensure that all questions in the questionnaire were answered. At the same time, he could also ensure that the correct number of learners per school completed the questionnaire.

Criteria for quality

In an effort to increase the validity of the questionnaire, attention was paid to form and content validity (cf. Pieterson & Maree, 2007). A statistician, as well as another specialist in the field of research looked at the questionnaire before it was distributed, in order to establish the validity of the instrument and to determine whether it entirely covered the content of the research area. The use of the existing instrument enhanced the validity of the study (cf. Bless, Higson-Smith & Kagee, 2006). A pilot study was undertaken. After ten learners from a senior secondary school, which was not involved in the research, had completed the questionnaire, changes to the content and structure of the questionnaire were made. The internal consistency of the measurement of the items of the three scales of the CSCSS-SF was calculated with the help of Cronbach's coefficient. The alpha coefficients for school safety, school culture and school climate and school violence scales were 0.709, 0.760, and 0.815, respectively. The internal consistency was at acceptable levels (cf. Pieterson & Maree, 2007).

Processing of data

To investigate the research hypothesis, a hierarchy regression analysis was done. In this case, school culture and school climate, as well as school safety are the independent variables, while school violence is the dependent variable. School violence is measured with three scales (physical and verbal harassment; weapons and physical attacks; and sexual harassment) and will be used separately in the analysis. The procedure that was followed was, firstly, to determine the total variance declared jointly by the predictor variables (entire model) with regard to the criterion (violence in the school), i.e. initially, all the predictors are entered jointly to determine the % variance that explains it all together. After that, the contribution of the set of variables (culture and climate, and school safety) was investigated, as well as the unique contribution of each individual predictor (the scales of school culture and school climate) to determine the explanation of the variation in school violence. The variance percentage explained by the specific variant(s) is indicated by the R2 (quadrated, multiple-correlation coefficient). In order to establish whether a specific variant or set of variants' contribution to the R2 value is statistically significant, it will be examined with the help of the hierarchic F test.

The 1% level of significance is used in this study. In order to arrive at a decision about the practical importance of statistically significant results that were found in the research, one must look at the practical significance of the results. In regression analysis, an effect size is indicated by f2 and it gives an indication of the contribution to R2 in terms of the proportion of unexplained variance of the previous model. The following guiding values (f2) were used in the regression analysis: 0.10 = little effect; 0.5 = medium effect and 0.35 = major effect.

Results related to the research hypothesis are provided against the background of descriptive statistics (averages and standard deviations) with regard to the school violence subscales. The scale values are calculated by adding the number of items and dividing it by the number of items (physical and verbal harassment = 7 items; weapons and physical items = 5 items; sexual harassment = 2 items). The mean in terms of the scale width (1-5) is calculated in this manner. The standard deviations, which indicate variability and changeability, are calculated as the square root of the mathematical average of the squares of the deviation of the different scores from the mathematical average of the division.

Statistical processing was done with the help of the SPSS-computer software.

Ethical aspects

The applicability of the principle of consent was already visible in the initial stage of the research project. A supportive letter of motivation from the University of the Free State was attached to the letter of application to the Eastern Cape Department of Education (Cohen et al., 2003). The participants' dignity, privacy and interests were respected at all times. The questionnaires did not contain any identifying aspects, names, addresses or code symbols. Before completing the questionnaires, the learners were also informed that the process was completely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any stage during the process. The first author, who was present at all times during the completion of the questionnaires, was available, if necessary, to support or refer traumatised respondents.

Results and discussion

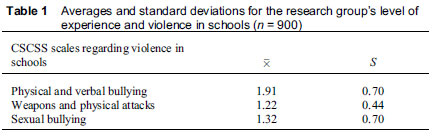

For the sake of the conceptualisation of the hypothesis it is necessary to provide the level of experience of the research group regarding school violence during the twelve months prior to the study (Table 1).

All the mean scores for the respondents' level of experience of school violence are under two out of a possible score of five. This indicates that in all three the subscales of school violence respondents indicated that they had been subjected to school violence. However, the assumption can be made that the schools are relatively safe places.

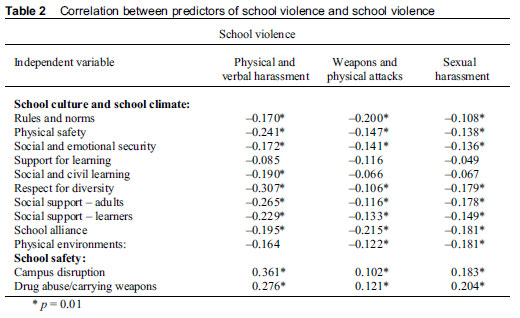

The correlation between predictors of school violence (school culture, school climate and school safety) and school violence was calculated with Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient. The information is captured in Table 2.

The correlation coefficient in Table 2 firstly indicates that, with the exception of one school culture and school climate scale, namely support for learning, all the other scales (school culture, school climate and school safety) are at the 1% level significant correlations with the violence scale physical and verbal harassment. Secondly, it seems that, with the exception of one school culture and school climate scale, namely social and citizen leaning, all the other scales (culture, climate and school safety) are at the 1% level significant correlations with the violence scale weapon and physical attacks. Thirdly, it seems, with the exception of two school culture and school climate scales, namely support for learning and social and citizen learning, all the other scales (culture, climate and school safety) are at the 1% level of significant correlation with the violence scale sexual harassment. All the school culture and school climate scales show a negative correlation with the three violence scales. All the school safety scales which relate to the lack of safety indicate a statistically significant positive correlation with the violence scales. It follows that, the better the school culture and school climate at a school, the lower the levels of school violence, while the lack of school safety contributes to learners experiencing higher levels of violence at schools.

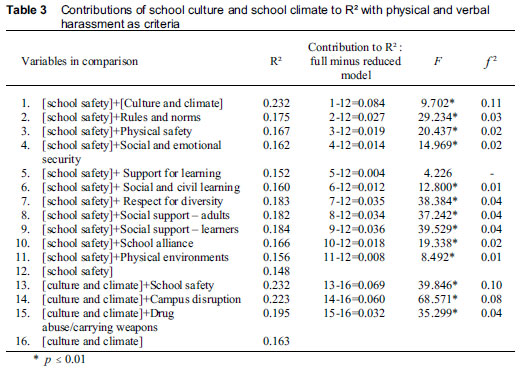

Because school violence comprises three scales, independent hierarchical regression analyses for each of the scales must be done. The results for physical and verbal harassment are captured in Table 3.

From Table 3 it is clear that the total group of predictors (culture, climate and school safety) combined explain 232% of the variance in physical and verbal harassment. This calculated R2 value is significant on the 1% level [F12;887sup> = 22.364; p < 0.0001].

The ten school culture and school climate aspects combined explain 8.4% of the variance in physical and verbal harassment of learners. This presentation is significant on the 1% level [F(10;887) = 9.702]. The corresponding f2 value (0.11) is significant of a result with average practical value. Related to what the contributions of individual school culture and school climate scales are, results in Table 3 indicate that, with the exception of one scale - support with learning - all the other scales on the 1% level contribute to the explanation of the variants in physical and verbal harassment. The corresponding effect sizes indicate that the results are not of practical importance. The two school safety aspects combined explain 6.9% of the variant in physical and verbal harassment of learners. This presentation is significant on the 1% level [F(2;887) = 39.846]. The corresponding f2 value (0.10) is significant of the result with average practical value. With regard to the individual school safety aspects, results in Table 3 indicate that both scales on the 1% level provide a unique contribution to the explanation of the variants in physical and verbal harassment. The corresponding effect sizes indicate that the results are not of any practical importance.

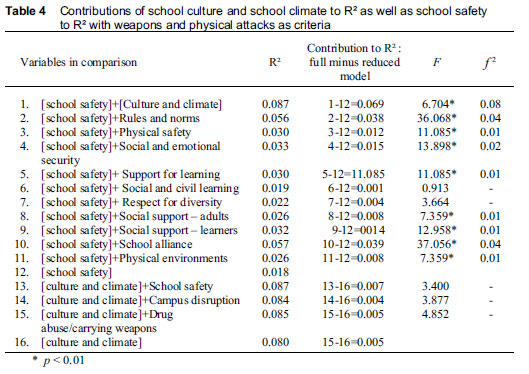

It seems then that, with the exception of a few individual aspects, the individual as well as combined school culture and school climate, together with aspects of school safety, contribute uniquely to physical and verbal harassment at schools. The results of weapon and physical attacks are captured in Table 4.

From Table 4 it is clear that for the total group of learners, the predictors (school culture, school climate and school safety) jointly explain 8.7% of the variance in weapon and physical attacks. This calculated R2 value is significant on the 1% level [F12;887= 7.062; p < 0,0001]. The ten aspects of school climate and culture jointly explain 6.9% of the variance in weapon and physical attacks of learners. This presentation is significant on the 1% level [F12;887= 6.704]. The corresponding f2 value (0.08) is significant of a value with no practical value. With regard to the contributions of the individual scale of school culture and school climate, the results in Table 4 show that with the exception of two scales, social and citizen learning, as well as respect for variety, all the other scales on the 1% level uniquely contribute to the explanation of the variance in weapon and physical attacks. The corresponding effect sizes indicate that the results are of no practical importance. It seems that the aspects of school culture and school climate are important joint contributors to weapon and physical attacks at schools.

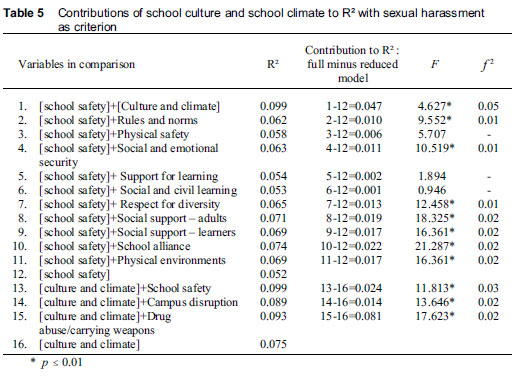

The two school safety aspects jointly explain 0.7% of the variance in weapon and physical attacks on learners. This presentation is not significant on the 1% level [F12;887= 3.400]. With regard to the contributions of the individual school safety scales, the results in Table 5 show that the individual scale also did not succeed in explaining a significant presentation of the variance in weapon and physical attacks. It seems that school safety does not contribute significantly to the explanation of the variance in weapons and physical attacks (as forms of violence).

The results of sexual harassment are captured in Table 5.

From Table 5 it is clear that the total group of predictors (school culture, school climate and school safety) jointly declare 9.9% of the variance in sexual harassment. The calculated R2 value is significant on the 1% level [F12;887 = 8.082; p < 0.0001].

The ten aspects of school culture and school climate jointly declare 4.7% of the variance in the sexual harassment of learners. This presentation is significant on the 1% level [F10;887= 4.627]. The corresponding f2 value (0.05) is significant of a result with no practical value. Regarding contributions from the individual scales of school culture and school climate, the results in Table 5 indicate that with the exception of three scales - physical safety, support with learning and social and citizen learning - all the other scales contribute uniquely on the 1% level to the explanation of the variance in sexual harassment. The corresponding effect sizes indicate that the result is of no practical importance.

The two school safety aspects jointly declare 2.4% of the variance in the sexual harassment of learners. The presentation is significant on the 1% level [F2;887= 11.813]. The corresponding f2 value (0.03) is significant of a result with no practical value. With regard to the contribution of individual school safety scales, the results in Table 5 indicate that both scales are on the 1% level and uniquely contribute to the explanation of the variance in sexual harassment. The corresponding effect sizes, however, indicate that the result is of no practical value.

Conclusion

Although crime and violence is a way of life in South Africa in general (Le Roux & Mokhele, 2011) and in the Eastern Cape Province in particular (Mlisa, Ward, Flisher & Lombard, 2008), schools in the Eastern Cape are nevertheless, relatively safe places (cf. Table 1). Whereas Arnette and Walsleben (1998) are of the opinion that school violence is nothing more than community violence which penetrates schools, this study is underpinned by Benbenishty and Astor's (2005 & 2008) theoretical model which places the school context, which includes school culture and climate, at the centre of school violence. Findings from studies that have shown that schooling has a profound influence on school violence (Bandyopadhyay, Cornell & Konold, 2009; Benbenishty & Astor, 2005; Harber, 2002, 2008; Morrell, 2002; Potts, 2006) resonate well with results from this study.

The results of this study, namely, that the better the school culture and school climate are at a school, the lower the level of school violence, as well as the fact that the lack of school safety contributes to learners experiencing higher levels of violence at schools, is in line with the findings by Benbenishty and Astor (2005), Sullivan and Keeney (2008) and Cavanagh and Delhar (2001). The separate hierarchic regression analyses of the school violence scales indicate that with the exception of some school culture and school climate, as well as school safety scales, the CSCSS-SF scale can be used to explain the variance in verbal and physical, as well as in sexual harassment. The results of the hierarchic regression analysis can also explain the influence of school climate and school culture on weapon and physical attacks. Neither the results of the combined aspects, nor the individual school safety scales indicate that this scale can provide a statistically significant contribution to explain the variance weapon and physical attacks. The f2 value for the total school culture and school climate and school safety aspects indicate a moderate practical value regarding only one variant namely, physical and verbal harassment. The f2value of the ten individual scales for school culture and school climate and the two scales for school safety indicate a result with no practical value.

Many researchers emphasise the importance of developing a positive school culture and school climate to reduce school violence and create safe schools that are conducive to teaching and learning (Benbenishty & Astor, 2005; Bucher & Manning, 2005; Le Roux & Mokhete, 2011; Rhodes, Stevens & Hemmings, 2011). The reality of school violence in Eastern Cape schools, as well as the correlation between the predictors of school violence (school culture, school climate and school safety) and school violence consequently emphasise the need for the establishment of a positive school culture and school climate as a way of addressing school violence. Benbenishty and Astor (2005) suggest that schools should attend to the following components of school culture and school climate in their quest to reduce school violence and create safe schools:

• School policy against violence. Schools should have policies that include clear, consistent and fair rules to reduce violence.

• Teacher support for learners. Supportive relationships may reduce learners' alienation towards their school and give them a chance to develop positive relationships with adults who may support, counsel and help them overcome their emotional and behaviour problems.

• Learners' participation. School policies and teacher support of learners may be more effective if they include learner participation in decision making and in the design of strategies to prevent/reduce violence.

Although this study contributes to the enhancement of the literature on school violence, it has limitations. This research was investigative in nature. No claims can be made with regard to the universal application of the results. The research, however, can act as a challenge for future researchers to attempt to confirm or question the results. Should this happen, the study will have succeeded in its overarching goal, namely to determine whether school culture and school climate have an influence on school violence. This study was aimed only at learners from Grade 10 to 12. To gain a broader perspective on the influence of school culture and school climate on school violence, all learners at the schools, as well as teachers and parents should be involved. Research findings are not contextualised in this article. A follow-up article will place findings within the socio-political and economic context of the Eastern Cape in general, and the demographic context of participating schools, in particular.

References

Arnette JL & Walsleben MC 1998. Combating fear and restoring safety in schools. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. US Department of Justice. Available at http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/167888.pdf. Accessed on 15 November 2007. [ Links ]

Bandyopadhyay S, Cornell DG & Konold TR 2009. Validity of three school climate scales to assess bullying, aggressive attitudes and help seeking. School Psychology Review, 38:338-355. [ Links ]

Barnes AK 2010. Die uitwerking van skoolkultuur en -klimaat op geweld in Oos-Kaapse skole: 'n onderwysbestuurperspektief. Unpublished PhD thesis. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Barth RS 2002. The culture builder. Educational Leadership, 59:6-11. [ Links ]

Benbenishty R & Astor RA 2008. School violence in an international context: a call for global collaboration in research and prevention. International Journal of Violence and School, 7:59-80. [ Links ]

Benbenishty R & Astor RA 2005. School violence in context. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bender G & Emslie A 2010. Prevalence and prevention of interpersonal violence in urban secondary schools: an ecosystemic perspective. Acta Academica, 42:171-205. [ Links ]

Berkowitz MW & Bier MC 2005. What works in character education: a report for policy makers and opinion leaders. Character Education Partnerships. Available at http://www.ecs.org/html/projectsPartners/nclc/docs/school-climate-challenge-web.pdf. Accessed on 5 June 2007. [ Links ]

Bernstein L 1992. Where is reform taking place? An analysis of policy changes and school climate. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 14:297-302. [ Links ]

Bless C, Higson-Smith C & Kagee A 2006. Fundamentals of social research methods. An African perspective. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Brown GJ & Henry D 1992. Using the climate survey to drive school reform. Contemporary Education, 63:277-280. [ Links ]

Buchner KT & Manning ML 2005. Creating safe schools. The Clearing House, 79:55-60. [ Links ]

Cavanagh RF & Delhar GB 2001. School improvement: organisational development or community building? Paper presented at the 2001 Annual Conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education. Available at http://www.aare.edu.au/01pap/del01143.htm. Accessed on 24 June 2009. [ Links ]

Cohen J & Pickeral T 2007. How measuring school climate can improve your school. Commentary in Education Week. 18 April. Available at http://www.philipwarring.us/on_education/2007/05/school_climate,html. Accessed on 3 June 2007. [ Links ]

Cohen J, McCabe L, Michelli NM & Pickeral T 2008. School climate: research, policy, practice and teacher education. Teachers College Record, July 2008. [ Links ]

Dunbar-Krige H, Pillay J & Henning E 2010. (Re-)positioning educational psychology in high-risk school communities. Education as Change, 14:3-16. [ Links ]

Dwyer K, Osher D & Wagner C 1998. Early warning, timely response: a guide to safe schools. Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services, Office of Special Education Programmes. US Department of Education. Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Fisher DL & Fraser BJ 1991. Validity and use of school environment instruments. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 26:13-18. [ Links ]

Freiberg HJ & Stein TA 1999. School climate. Measuring, improving and sustaining healthy learning environments. London: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Gruenert S 2008. School culture, school climate: they are not the same thing. The Principal, 56-59. Available at http:wwwnaesp.org/resources/2/Principal/2008/M-p56.pdf. Accessed on 20 March 2009. [ Links ]

Harber C 2002. Schooling as violence: an exploratory overview. Educational Review, 54:7-16. [ Links ]

Harber C 2008. Perpetrating disaffection: schooling as an international problem. Educational Studies, 34:457-467. [ Links ]

Herr K & Anderson GL 2003. Violent youth of violent schools. A critical incident analysis of symbolic violence. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 6:415-433. [ Links ]

Hinde ER 2004. School Culture and Change: an examination of the effects of school culture on the process of change. Arizona State University West. Availabale at http://usca.edu/essays/vol122004/hinde.pdf. Accessed on 13 November 2009. [ Links ]

Johnson WL, Johnson AM & Zimmerman K 1996. Assessing school climate priorities: a Texas study. The Clearing House, 70:64-66. [ Links ]

Johnson B & Stevens JJ 2006. Student achievement and elementary teachers' perceptions of school climate. Learning Environment Res. Available at http://www.ed.arizona.ed/perc/Johnson%20School%20climate.pdf Accessed on 25 June 2007. [ Links ]

Khumalo G 2008. Education Department committed to school safety. BuaNews Online. 7 February 2008. Available at http://www.buanews.gov.za/view. php?ID... buanew08. Accessed on 20 August 2009. [ Links ]

Klewin G, Tillman K & Weingart G 2003. Violence in school. In Heitmeyer W & Hagan J (eds). International handbook of violence research. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

Le Roux CS & Mokhele PR 2011. The persistence of violence in South African schools: in search of solutions. Africa Education Review, 8:318-335. [ Links ]

Mlisa LN, Ward CL, Flisher AJ & Lombard CJ 2008. Bullying in rural high schools in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa: prevalence, and risk and protective factors at school and in the family. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 18:261-268. [ Links ]

Morrell R 2002. A calm after the storm? Beyond schooling as violence. Educational Review, 54:37-46. [ Links ]

Najaka SS, Gottfredson DC & Wilson DB 2002. A meta-analytic inquiry into the relationship between selected risk factors and problem behaviour. Prevention Science, 2:267-271. [ Links ]

Ninan M 2006. School climate and its impact on school effectiveness and improvement at Fort Lauderdale. Available at http://www.leadership.fau.edu/icsei2006/Papers/ninan.pdf. Accessed on 6 July 2007. [ Links ]

Pieterson J & Maree K 2007. Standardisation of a questionnaire. In K Maree (ed.). First Steps in Research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Peterson KD & Deal TE 2002. The shaping school culture fieldbook. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Publishers. [ Links ]

Potts A 2006. Schools as dangerous places. Educational Studies, 32:319-330. [ Links ]

Reames EH & Spencer WA 1998. Teacher efficacy and commitment: relationships to middle school culture. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association. San Diego, CA, April 13-17. [ Links ]

Rhodes V, Stevens D & Hemmings A 2011. Creating positive culture in a new urban high school. The High School Journal, 82-94. [ Links ]

Robbins P & Alvy HB 2009. The Principals Companion: Strategies for Making the Job easier. 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Saufler C 2005. School climate and culture. Maine's Best Practices in Bullying and Harassment Prevention. Available at http://www.safeschoolsforall.com/schoolclimate.html. Accessed on 7 November 2009. [ Links ]

Short PM & Rinehardt JS 1992. School participant empowerment scale: assessment of level of empowerment within school environment. Educational and Psychology Measurement, 52:951-960. [ Links ]

Squelch J 2001. Do school governing bodies have a duty to create safe schools? Perspectives in Education, 19:137-149. [ Links ]

Sullivan E & Keeney E 2008. Teachers talk: school culture, safety and human rights. New York: National Economic & Social Rights Initiative. [ Links ]

Van der Westhuizen CN & Maree JG 2009. The scope of violence in a number of Gauteng schools. Acta Criminologica, 22:43-62. [ Links ]

West CA 1985. Effects of school climate and school social structure on student academic achievement in selected urban elementary schools. Journal of Negro Education, 54:451-461. [ Links ]

Zulu BM, Urbani G & Van der Merwe A 2004. Violence as an impediment to a culture of teaching and learning in some South African schools. South African Journal of Education, 24:170-175. [ Links ]