Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.31 n.2 Pretoria Jan. 2011

ARTICLES

Care and support of orphaned and vulnerable children at school: helping teachers to respond

Lesley Wood*; Linda Goba

ABSTRACT

It is acknowledged that teacher training programmes around HIV in most of sub-Saharan Africa appear not to have been very effective in assisting teachers to respond to the demands placed on them by the pandemic. In response to the need identified by international development agencies, for research into teacher education and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, this study investigated teacher perceptions of the effectiveness of training programmes offered in a specific school district in South Africa to equip them to deal with issues arising from having orphans and vulnerable children in their classrooms. A qualitative research design was followed to purposively select teachers who had attended the departmental training to participate in focus groups to explore the phenomenon of teaching orphaned and vulnerable children. The findings that emerged from the thematic data analysis provided supporting evidence that current teacher education approaches in this regard are not perceived to be effective. The results are used to suggest guidelines for an alternative approach to the current forms of HIV and AIDS training for teachers that is more likely to be sustainable, culturally appropriate and suited to the context.

Keywords: in-service teacher education; HIV and AIDS; orphans; quality of education; teacher education; vulnerable children

Introduction

We report on a study that was initiated as a response to an appeal for research into teacher education and HIV to "provide evidence-based guidance for ministries of education (MOEs) on how to make initial and in-service teacher education effective" (Clarke, 2008:71). The training programmes introduced by MOEs in most of sub-Saharan Africa seem not to have enjoyed much success, tending to lack in structure and focus (Kelly, 2002). We propose that programmes based on the real needs and experiences of teachers are more likely to be sustainable, culturally appropriate and suited to the context. This study thus explored teacher perception of the training programmes offered in a specific school district in South Africa, and in particular how teachers perceived themselves to have been equipped to deal with issues that arise as result of having orphaned and vulnerable children in their classrooms. The findings that emerged from this qualitative study are used to suggest guidelines for an alternative approach to the current forms of HIV and AIDS training for teachers that is more responsive to the lived experience of teachers involved at grassroots level.

Background to the research

The quality of teaching and learning in Sub Saharan African schools is under severe threat as the amount of orphaned and vulnerable children (OVC) escalates (Govender, 2004; Hepburn, 2002), worsening the existing socio-economic problems experienced in the mostly disadvantaged communities (Carr-Hill, Kataboro & Katahoire, 2000). The number of orphans in sub-Saharan Africa was estimated to be around 11.6 million in 2007 (UNAIDS, 2008) - the number of children who have been rendered vulnerable by the pandemic is inestimable. The term OVC refers to any child whose level of vulnerability has increased as a result of HIV and AIDS and could include any child under the age of 18 who falls into one or more of the following categories (Smart, 2003:viii): has lost one or both parents or experienced the death of other family members; is neglected, destitute, abandoned or abused; has a parent or guardian who is ill; has suffered increased poverty levels; has been the victim of human rights abuse; is HIV positive themselves.

It is evident that the above definition of OVC could apply to the majority of learners in South Africa. For teachers, therefore, there is no escaping the impact of the pandemic on the lives of their learners, resulting from an increased incidence of social, emotional, physical, economic and human rights problems (Carr-Hill et al., 2000; Culver, 2007; Ebersöhn & Eloff, 2002; Foster, 2002). The consequences of such problems are played out in the classroom (Hepburn, 2002), as teachers struggle to balance the already challenging business of teaching and learning with the additional demands imposed by the increased levels of anxiety, limited concentration spans, severe trauma, heightened discrimination and stigma, and increased poverty experienced by learners living in this age of AIDS (Foster & Williamson, 2000; Wood, 2009).

It has long been internationally recognised that well-motivated and competent teachers are a pre-requisite for the delivery of quality education (Oxfam, 2000). However, although many countries have developed multi-sectoral responses to meet the needs of OVC (Pridmore & Yates, 2000; Richter, Manegold & Pather, 2004), few Ministries of Education in sub-Saharan Africa seem to have directed attention to, or invested resources in teacher education for this purpose (Clarke, 2008).

Example of current training opportunities for teachers

Prior to 2005, the training programmes offered by the Department of Education in the Eastern Cape, South Africa focused on equipping teachers with knowledge about the transmission of the virus and information on preventative measures (Goba, 2009), through the roll out of life skills programmes in schools (Department of Health, 2003/4; Peltzer & Promtussananon, 2003). In 1997, 10,000 secondary school teachers (two in each school in each province) were targeted to be trained in life skills teaching, but the monitoring and evaluation of this initiative did not give a clear indication of how successful this training was (Harrison, Smith & Meyer, 2000). However, it was apparent that teachers received more training in prevention education, through the medium of life skills, than in how to care for and support the growing number of OVC in their schools.

Within the National Integrated Plan (NIP), rolled out in 2005 for children infected and affected by HIV and AIDS (Department of Health, 2003/4), some attention has been given to care and support, as evidenced by the inclusion of training on how to set up a Health Advisory Committee (HAC) and training in basic counselling. In the specific district where this study was carried out, the Department of Education HIV and AIDS training programmes for teachers were designed and presented by non-governmental agencies (NGOs), who usually have a narrow focus (e.g. reproductive health/promotion of Christian values), and whose programmes may not take cognisance of the curriculum demands and other educational complexities that teachers have to deal with when implementing the National Curriculum (Clarke, 2008).

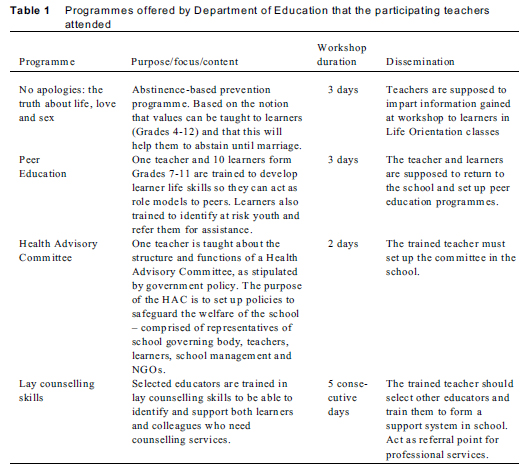

Table 1 outlines the four programmes offered by the Department of Education in the Eastern Cape during 2008. These programmes were offered only to Life Orientation teachers at both secondary and primary schools. Each school in the province was requested to send one teacher. For ethical reasons, the NGOs who offered the programmes have not been identified by name.

Although the "No apologies" and the Peer Education programmes primarily targeted prevention through the development of life skills in learners, the Health Advisory Committee training and the lay counselling training could be seen as an attempt to equip teachers to address the needs of OVC. The content of the programmes were decided on by the relevant NGO who was appointed at a provincial level, and therefore the same programme was offered to teachers all over the Eastern Cape province, irrespective of their specific contexts and environments (e.g. rural or urban). It is interesting to note that the main focus for prevention from Grades 7-12 was on abstinence, even although research has shown that abstinence only programmes have not been successful in reducing risky sexual behaviour (Bruckner & Bearman, 2005; Pisani, 2008). In keeping with most HIV programmes in education in sub-Saharan Africa, the teacher is framed as a service deliverer whose main aim is to protect the learner from HIV infection or to render care and support (Clarke, 2008). Teachers' personal and professional needs in this regard do not seem to have received much attention, nor has the wisdom gained from personal experience of teachers been factored into the training.

Methodology

Working within an interpretive paradigm (Denzin & Lincoln, 2008:31), a qualitative approach was chosen to answer the main research question, "How can teachers best be facilitated to deal with OVC-related issues in schools?" Two sub-questions also emerged during the research:

1. What are the perceived needs of teachers with regard to the support of OVC?

2. What recommendations can be made to better equip and support teachers to deal with OVC issues in schools?

A qualitative approach allowed us to assemble a multi-faceted and holistic picture of the teachers' experiences, perceptions and feelings about the topic (Creswell, 2005).

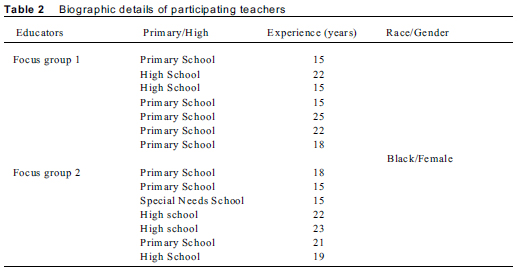

In keeping with the qualitative approach, purposive sampling was employed (De Vos, 2002) to choose 12 schools situated in disadvantaged urban township areas where it was assumed there was a greater likelihood that teachers would have to deal with OVC issues. Teachers eligible for the study had to have completed the four training workshops offered by the Department of Education (see Table 1), and thus were all teachers of the learning area, Life Orientation. Fourteen volunteer teachers, all female, were assigned to two focus groups (seven in each) to ensure a good mixture between high and primary schools. The biographic details of the participants are contained in Table 2.

Data were collected by means of unstructured focus group interviews to encourage spontaneity and in-depth discussion of participant experiences (Denzin & Lincoln, 2008). A co-moderator sat in to take field notes, which were discussed with the researcher immediately after the interviews, as suggested by Robson (2002).

One central question was posed, namely: What was your experience of the training programmes with regard to equipping you to deal with OVC issues?

The interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. Two interviews, with seven participants in each, were conducted before data saturation was deemed to be reached (Greeff, 2005), since the themes that emerged in the first interview were repeated in the second.

Data analysis was conducted by Tesch's suggested steps in Creswell (2005:238) to identify emerging themes, which were then supported by direct quotes of the participants and controlled against literature (Woods & Cantazaro, 1998). The data was verified against Guba's model of trustworthiness, using the criteria of truth-value (explanation of research methodology, use of an independent re-coder and data triangulation), applicability (rich description of methodology and data), consistency (detailed description of process) and neutrality (co-moderator used as observer in interviews) (Krefting, 1991:214-222).

The usual ethical considerations of informed consent, anonymity and voluntary participation were adhered to (Strydom, 2002) as attested to by the ethical clearance obtained from the ethics committee of the University where the researchers worked. Teachers who had completed the four training programmes participated voluntarily, and they signed consent forms indicating that they understood the purpose and process of the research, that their identity would not be revealed and that they could withdraw at any time.

Data analysis and findings

Data analysis revealed that the teachers did not perceive themselves to have been adequately equipped to deal with OVC issues. It was also evident that the teachers were experiencing many difficulties in transferring what they had learnt into action, and that they experienced needs that were not addressed in the training. The emergent themes, supported by direct quotations from the teachers, will be discussed in relation to relevant literature.

The following themes emerged from the data analysis:

Theme 1: Teachers experienced difficulties in translating knowledge into action

All the teachers in the focus groups were adamant that they could not implement what they had learnt in the training, although theoretical knowledge and attitudes were improved.

The participant teachers reported that the training courses had equipped them with knowledge and improved their attitudes with regard to dealing with OVC issues:

The Department of Education's workshops have helped a lot in changing our attitude.

I do not mind and do not care what they say [negative colleagues] because I am not just there to earn a salary, but to serve the learners as well.

Other studies have shown that in-service training for HIV and AIDS increases knowledge and improves attitudes of teachers (Doherty-Poirier, Munro & Salmon, 1994), but does not necessarily improve their level of comfort in talking about HIV and AIDS (Peltzer & Promtussananon, 2003), particularly in matters related to homosexuality and safer sex (Dawson, Chunis, Smith & Carboni, 2001). Past experience has taught us that if teachers are uncomfortable with the subject matter, it is likely that they will tend to avoid it (Visser, 2004) or discuss it in a way that precludes real learner engagement and learning (Chege, 2006). Kirby, Obasi and Laris (2006) reported a positive change in teacher knowledge and behaviour after training, but only if the training programmes were designed according to certain principles. These included: the involvement of multiple stakeholders with different experiences and views; a thorough needs assessment of teacher needs; and the design of content that is commensurate with community values and available resources - none of which the training programmes the participants attended seemed to adhere to.

Although the counselling course was mentioned as being particularly useful in helping them to be more approachable and more empathic towards learners, participants also stated that they did not have enough skills to do more than simply listen. In addition, because their colleagues thought they were now trained counsellors, they referred all problem cases to them. This was seen as a predicament, because they did not feel equipped to offer the necessary help:

I would like to help, but because of the circumstances under which we are working, there is a fear that you might be overstepping your position and yet, ee! ... as a result of that you become reserved and you do not want to go beyond limits.

The development of counselling skills and the confidence to implement them takes time and the opportunity to practice in a supportive environment (Egan, 2002). When counselling OVC, their caregivers or parents, teachers are called on to discuss sensitive issues such as poverty, death, illness and other related social issues and this expertise cannot be acquired on a short term course with no follow-up (Baggaley, Sulwe, Chilala & Mashambe, 1999).

There is no monitoring at all. Only when the facilitator wants to submit their claims for payment, and they need our input, they will pressurise you to fill in an evaluation form, asking for feedback about the effectiveness of the workshops in writing. In all the DOE workshops I have attended, there was no follow-up afterwards - you don't even know who to contact when you get stuck.

We only gained some knowledge through attending workshops, which are sometimes a day or three days, this is not long enough.

It is apparent that the courses did not do more than provide knowledge, and that there was little emphasis on how to implement that knowledge back at the school. There was no training offered on ways to get the rest of the school involved or on how to overcome the shortage of resources that presents severe barriers to implementation, in the eyes of the teachers.

The lack of attention given to implementation within the programme design could be a result of using training agents who are not part of the school system, and who therefore are not familiar with the circumstances and contexts in which teachers work, or with the curriculum requirements (Clarke, 2008). Continuity of training, coupled with skills on community mobilisation, is essential if successful implementation of training is to take place (Gordon, 2006). Another barrier to taking action could be the fact that the courses under discussion, with the exception of the life skills programme, cannot be integrated into the curriculum and require "extra-mural" activities of the Life Orientation teachers and those they wish to involve - something that time-strapped and stressed teachers may find difficult to do (Van Laren & Ismail, 2009).

Theme 2: Life Orientation teachers are stressed by their perceived marginalisation and increased role expectations

The participant Life Orientation (LO) teachers all experienced a sense of marginalisation, since they were the only teachers targeted for HIV training by the Department of Education. After training, when trying to involve colleagues in initiatives to address OVC issues, the responses they received were often similar to the following:

Oh, it is this thing again. Oh, it is the LO teacher and her AIDS. Whenever you come up with an idea, there will be looks and gossip:"Who do you think you are? - if you are so good, you can do it yourself!"

Adding to this external resentment, the LO teachers themselves were indignant, because they did not think that they had been adequately trained for the assigned role of "AIDS expert":

Being the LO teacher makes people think you are trained in all aspects, whereas we are like any other teacher, trained just to teach learners.

The targeting of only LO teachers for HIV training is contrary to the Department of Education's (2003:5) statement that it is the responsibility of all teachers to address OVC issues, calling for a "coherent response" to HIV and AIDS in schools. The lack of training for other teachers was perceived to result in their "being left behind", increasing the schism between those who are identified as able to deal with HIV and AIDS and those who are not. This situation does not create a safe and enabling climate conducive to team work, one of the prerequisites for effective training interventions (Kirby, Obasi & Laris, 2006).

Participants also experienced stress as a result of feeling responsible for responding to the needs of the children:

HIV and AIDS has truly affected our schools, it has a negative impact and its presence is felt by all, by children in the classroom ... learner performance drops, children's health deteriorates ... the teacher is left to cope with things they have no training for ... this makes it very difficult for all of us.

The participant teachers felt the pain of their learners, leading them to try to provide for their needs in the absence of a coordinated response from the school. For example, one teacher described how they tried to cook for their hungry learners, bridging the gap left by parents who could not provide the learners with their basic needs:

A child will complain of a headache, and you will find out that she had nothing to eat, except for what we gave her, meaning that we are parents to these learners because of the fact that these learners are orphans and vulnerable children.

This sense of responsibility adds to the stress in the lives of the teachers, since it is unlikely that they can meet all the needs of these children, particularly in the absence of cooperation from the rest of the school community (Wood, 2009). In the words of one participant, this creates a "lose-lose" situation, as the other learners are deprived of the teacher's full attention; the teacher is emotionally affected by the plight of the affected learner, which further diminishes capacity to forge ahead with the prescribed syllabus; she therefore falls behind and this creates more stress - no one can benefit under these circumstances and the quality of teaching and learning is understandably severely impacted. They reported incidents of having to follow up learner absenteeism, deal with the alienation of learners by their peers due to stigmatisation, struggle to get material and financial support for learners and offer emotional support to traumatised learners - all of which left little time for actual teaching and learning to take place:

At times, the process takes almost a day's tuition, and this affects you as an educator. I was trained to be an educator, but now the profession that I am in is now changing every day. I am also a social worker, as we have to assist them ... we also refer these learners to the clinics, in which we find ourselves being nurses.

The adoption of the roles of mentors, counsellors and welfare workers is not easy for educators, as reported in previous studies (Bhana, Morrell, Epstein & Moletsane, 2006; Coombe, 2003, Crewe, 2000). Teaching vulnerable children also calls for a good understanding of how to boost self-esteem and help them to development attachment (Subbarao & Cowey, 2004), factors that do not seem to have been addressed in the training.

Given the stress the participants in this study were experiencing, it would appear that they need to be helped to explore their understandings of the pandemic and how they could best respond to the needs of the learners, while containing and meeting their own emotional needs (Theron, 2007). The development of teachers' ontological and epistemological values and beliefs around HIV prevention and care, and their need for support and nurturing to cope with the added roles and expectations, seems to have been largely ignored in teacher training (Baxen, 2005; Wood, 2009) . The emphasis has been on how to "change" the learners to lessen the risk of infection, and not on how to adapt their own practices in order to best support and care for learners affected by HIV and AIDS.

The stress experienced as a result of having to take on additional responsibilities and roles was increased by the fact that, according to the participants, many teachers were themselves either infected and/or severely affected due to the illness of family members.

HIV and AIDS has a negative impact in the education sector ... teachers themselves are sick ... being absent ... it impacts on learners who are left with no supervision. We are suffering as a result of our families being HIV. Most of us here have to care for children of our sisters, our brothers who have passed on ...

The 2005 national survey (Hall, Altman, Nkomo, Peltzer & Zuma, 2005) indicated that the HIV prevalence rate among South African teachers was 12.7% in 2004, a figure that may in fact be higher, given the fact that most educators are unwilling to go for testing (Wood, 2009). In addition, many teachers are affected by the illness and/or death of loved ones, leaving them with major emotional and financial problems (Theron, 2005) that impact on their ability to respond to the needs of the learners. These factors do not seem to have been specifically addressed by the four programmes, since the participants were still experiencing high levels of stress after having undergone the training.

Theme 3: Teachers' perceptions of environmental barriers to provision of care and support to OVC

Provision of support to OVC was also hampered by perceived interpersonal and environmental barriers. One of the biggest problems facing teachers in addressing OVC issues, according to the participants, was the stigma attached to OVC. As one teacher said:

I have a learner who is HIV positive. However, the attitude I get from my colleagues is that the year was too long for them to see this learner pass onto the new class, for they regard it as a burden and an added responsibility to assist these learners.

Stigmatisation was not only confined to learners, but was also rife among the teachers themselves:

A person cannot get sick for an extended period of time, you will hear them passing remarks like "Did you see how thin he is?" You know, making insinuations and not giving the support they deserve.

Teacher attitudes have been found to play a significant role in determining the success or failure of HIV related educational interventions (Morrell & Ouzgane, 2005; Thorpe, 2005), therefore the development of a positive climate within the school is imperative for effective provision of care and support to OVCs.

The participating teachers also complained about the lack of support and cooperation from the Department of Education. Even although the Department employs specialists such as psychologists and social workers to address learner wellbeing, their services were not actually made available to the schools:

Yes, the DoE has specialists, but they claim that they are understaffed and cannot cater for our needs ...

Although it can be argued that every person in the educational arena should be a change agent (Fullen, 1993), it is evident that teachers are in need of expert assistance in dealing with the educational repercussions of social problems experienced by learners.

We really need more expertise to deal with this problem. Even those learners we think that things are normal with, they also have problems that are beyond their control.

The participating teachers did display a sense of agency, supporting the notion that they "have much to offer to the HIV debate" (Visser-Valfrey, 2004:224). They offered ideas around how social workers could be allocated to specific schools and how the DoE could cooperate more with the Department of Social Welfare so that teachers could work hand-in-hand with them to offer assistance to learners:

If these resources can be made available, the teachers are willing to make a positive impact, as they are the centre of all this ... and are able to assist first hand.

Although there is much rhetoric around the need for governmental ministries to work in an integrated way to address HIV and AIDS in education (Clarke, 2008), little of this seems to have been translated into practice.

The participating teachers also voiced a need for more support from school leadership. Since OVC issues require holistic intervention, they have to be part of a whole school improvement programme (Wood & Webb, 2008), related to policies on health and safety (Clarke, 2008). However, according to the participant teachers, most school principals and governing bodies do not have the necessary knowledge, skills or experience to strategically plan to address OVC issues from a holistic perspective. This is highlighted by the response of the participating teachers:

We have been advised by our principal to push them [OVC] to at least the next level [high school] so that they can be able to take care of themselves.

Although the LO teachers are expected to enlist the help of colleagues to implement their training, the lack of support by school management makes this almost impossible:

Even if you want to give feedback, your teacher colleagues and the principal do not show any interest, and refer this challenge to you to attend.

This was perceived as unfair by the participating teachers, since they had no choice in deciding whether or not to attend training, or even in choosing which learning areas to teach.

... in my school, you do not choose for yourself the learning area you are comfortable with - you are given any learning area to teach with no choice.

This implies that the teacher may not be happy to teach Life Orientation, but that they have no choice but to try and cope with the incumbent stressors - "you have no option but to swallow the pain and go ahead with the tuition."

Being overburdened with OVC issues, the LO teachers were forced to work longer hours in order to attend to their lesson preparation and assessment duties. This kind of problem is something that can only really be dealt with at school level under the leadership of the principal (Wood & Webb, 2008).

Conclusions and recommendations

The findings of this study offer little evidence of the training programme designers having consulted with teachers on the lived reality of teaching in a school where HIV and AIDS have increased the vulnerability of the majority of children. The current training workshops, while well-intentioned, position the teacher as a passive recipient of knowledge, rather than an active contributor to the construction of strategies based on expert knowledge and understanding of specific contexts (Visser-Valfrey, 2004). Curriculum development skills, the local context, and the differing needs of teachers need to be factored into any teacher training (Anderson, 2004; Lewin & Stuart, 2003; Monk, 1999) for it to be successful. Instead of drawing on the many years of valuable experience and insights that teachers can offer concerning the realities that may hamper implementation of training outcomes, the workshops have been mostly theoretical and generalised in nature.

The participating teachers believed that they would be able to provide valuable input to the course designers that would help them to reshape their workshops to increase their relevance. As the "heart of the school" (Wood, 2004:156) the teacher is more familiar with the daily demands of teaching vulnerable children than an outside agency, whose expertise may be based on an idealistic view of teaching and learning (Clarke, 2008), often impossible to operationalise given the disadvantaged conditions prevailing in the majority of sub-Saharan African schools (Badcock-Walters, Görgens, Heard, Mukwashi, Smart, Tomlinson & Wilson, 2005; Human Rights Watch, 2005). Standardised, 'one size fits all' programmes are also often founded on western cultural understandings and do not recognise the complex interplay of cultural and social norms that shape the behaviour of people socialised into African ecologies (Boler & Aggleton, 2004).

The findings also make it clear that there is a need for all teachers in the school to work together to address the care and support of OVC; there is a need for leadership to take the initiative to strategically and democratically plan how to approach the problems holistically and systematically; and there is a need for cooperation with outside agencies and other sources of support, including parents and the general community. These findings are supported by other studies that call for a comprehensive, holistic and coordinated approach to HIV and AIDS in education (Anderson, 2004; Clarke, 2008; UNESCO, 2008).

The training received by the participants tended to foreground the learner, rather than the teacher. Although learner needs are paramount, it cannot be assumed that every teacher possesses the necessary knowledge, skills, attitudes and values to respond to the emotional, material and educational needs of the vulnerable learner, or the ability to deal with their own heightened stress and emotional responses. Since the quality of education always depends on the quality of teachers (Carron & Chau, 1996), effective training for dealing with OVC issues has to focus more on their needs, so that they can be effective helpers (McBer, 2000).

The conclusions reached from the findings of this study indicate that the current approach to training teachers with regard to teaching and supporting OVC is beset with problems. It does not take into account the lived realities of teaching in communities that are plagued with the problems associated with endemic poverty and other social challenges. Rather than helping school communities to find workable solutions for offering support and care to OVC within their environment, it isolates a specific group of teachers who are then perceived to be solely responsible for offering care, support and protection to learners.

Based on the conclusions, it is recommended that a whole school approach to caring for OVC would be more suitable. Such an approach would enable a concerted, sustainable and context-appropriate response by all who are ultimately responsible for the care and protection of vulnerable children (Tang, Nutbeam, Aldinger, St Leger, Bundy, Hoffmann et al., 2009). As Clarke (2008:71) contends, "the effectiveness of HIV education is constrained by the wider crisis in education." Unless this "wider crisis" is addressed, then any training specifically aimed at dealing with the consequences of HIV is likely to be ineffective.

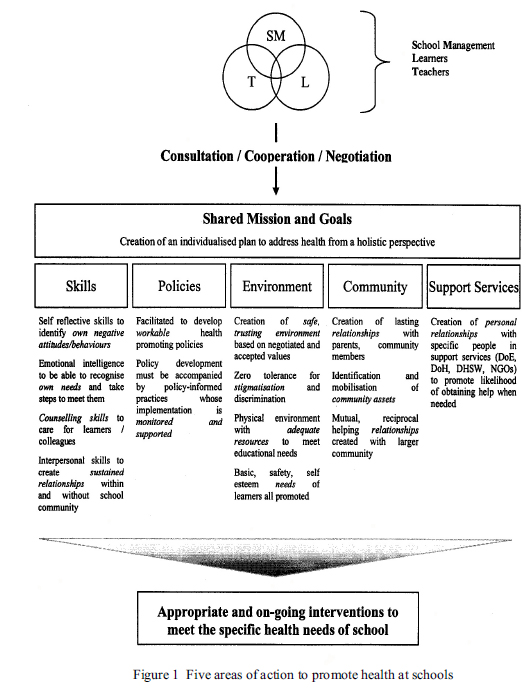

A Health Promoting Schools (HPS) approach (World Health Organisation (WHO), 1995) offers an ideal theoretical framework on which to base initiatives to protect, care and support for all children in the school who are potentially vulnerable (UNESCO, 2008). The definition of a health promoting school is "one that constantly strengthens its capacity as a healthy setting for living, learning and working" (WHO, 2007:1). Rather than taking one or two teachers from each school out of the classroom for once-off workshops, it may be better to send facilitators into schools to work together with all role-players in setting up a plan that is specific for their school, and that addresses the potential problems by making the best use of existing strengths and assets (Ebersöhn & Eloff, 2002). In this way, schools can self-generate specific solutions to their particular problems - the whole school system them becomes responsible for creating conditions that are conducive to the mental, physical, environmental and social health of learners and teachers, as well as families and community members, rather than the Life Orientation teacher alone.

An HPS approach would also help to reduce the stigma reported to be rife in the schools implicated in this study, since everyone is involved in setting up and receiving the services that promote health. HIV and AIDS are not singled out as the only threat to health, but become one of the many factors that are addressed to foster health and learning. The focus is on promoting knowledge, beliefs, skills, attitudes, values and support (WHO, 2007) that undergird healthy behaviour, thereby creating a climate that is less stigmatising and non-discriminatory.

Since the HPS approach is part of a global health initiative (WHO, 2007), there have been many evidence-based studies that suggest its effectiveness (Denman, Moon, Parsons & Stears, 2002; Department of Human Services, 2000; Lee, 2009; Rowling, 2003). It is compatible with, and has similar outcomes to, the concepts of inclusive education and whole school development (Moola, 2006), as it ensures that the environment adapts to meet the needs of the learner, rather than focusing on trying to 'fix' the learner experiencing barriers to learning.

Figure 1 illustrates how the main areas of concern voiced by the participating teachers (indicated by italicised text) can be addressed through these five areas.

The approach can be categorised into five main areas of action:

• the development of skills within the school community - this would address the reported need of the teachers to have every teacher, including the principal, educated about and facilitated to address OVC needs; all teachers could be trained in basic counselling skills and assisted to develop strategies to help them cope with stress and negative emotions they indicated they were experiencing. Skills in brokering and liaison with outside agencies could also be developed to assist them in engaging resources to address OVC social and material needs.

• the design and implementation of appropriate health promoting policies: the reported issues of stigmatisation and negative attitudes could be addressed by exploring these issues and developing policies to promote inclusion and non-discriminatory attitudes and practices. Policies could also be developed around how to offer material and emotional support to OVC, which would combat the need for individual teachers to try and provide basic needs as they are currently doing.

• the creation of healthy social, emotional and physical environments: school leadership could take the initiative to implement and monitor strategies that would promote the creation of a safe, trusting environment based on negotiated and accepted values and zero tolerance for stigmatisation and discrimination. Strategic goals could be set for equipping the physical environment with adequate resources to meet educational needs and promote the attainment of basic, safety and self esteem needs of learners.

• the advancement and involvement of community members, agencies and assets and the creation and nurturing of effective working relationships with specialised support services: the identification of community assets and negotiation as to their use would help to develop relationships with outside helping resources with whom the teacher and school could partner to address issues. The lived experiences of the teachers could then be taken as a starting point from which agencies could develop training and helping initiatives that would be truly responsive to the needs of the particular school.

References

Anderson L 2004. Increasing teacher effectiveness. (Fundamentals of Education Planning, No. 79). Paris: IIEP: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Badcock-Walters P, Görgens M, Heard W, Mukwashi P, Smart R, Tomlinson J & Wilson D 2005. Education access and retention for educationally marginalised children: innovations in social protection. Durban, South Africa: MTT/HEARD (University of KwaZulu-Natal). [ Links ]

Baggaley R, Sulwe J, Chilala M & Mashambe C 1999. HIV stress in primary school teachers in Zambia. Policy and Practice, 77:284-287. [ Links ]

Baxen J 2005. What questions: HIV/AIDS educational research: Beyond more of the same to asking different epistemological questions. UWC Papers in Education, 3:58-63. [ Links ]

Bhana D, Morrell R, Epstein D & Moletsane R 2006. The hidden work of caring: teachers and the maturing AIDS epidemic in diverse secondary schools in Durban. Journal of Education, 38:5-23. [ Links ]

Boler T & Aggleton P 2004. Life skills based education for HIV prevention: a critical analysis. (UK Working Group on HIV/AIDS and Education, Issue 3). London: Action Aid/Save the Children. [ Links ]

Bruckner H & Bearman P 2005. After the promise: the STD consequences of adolescent virginity pledges. Journal of Adolescence Health, 36:271-278. [ Links ]

Carr-Hill R, Kataboro JK & Katahoire A 2000. HIV/AIDS and Education. Available at http://www.harare.unesco.org/hivaids/view_abstract.asp?id=138. Accessed 15 November 2010. [ Links ]

Carron G & Chau T 1996. The quality of primary schools in different development contexts. Paris: IIEP-UNESCO. [ Links ]

Chege F 2006. Teachers' gendered identities, pedagogy and the HIV/AIDS education in African settings within the ESAR. Journal of Education, 38:25-44. [ Links ]

Clarke DJ 2008. Heroes and Villains: teachers in the education response to HIV. Paris: IIEP, Unesco. [ Links ]

Coombe C 2002. HIV/Aids and education. Perspectives in Education, 20:vii-x. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2005. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [ Links ]

Crewe M 2000. A University Response to HIV/AIDS. AIDS Analysis Africa, 10:5. [ Links ]

Culver L 2007. AIDS map news. Available at www.aidsmap.com/.../news. Accessed 12 November 2010. [ Links ]

Dawson LJ, Chunis ML, Smith DM & Carboni AA 2001. The role of academic discipline and gender in high school teachers' AIDS-related knowledge and attitudes. Journal of School Health, 71:3-8. [ Links ]

Denman S, Moon A, Parsons C & Stears D 2002. The Health Promoting School: Policy, Research and Practice. London: Routledge Farmer. [ Links ]

Denzin NK & Lincoln YS 2008. Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. 3rd edn. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2003. Design an HIV/AIDS plan for your school. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Health 2003/4. Tracking progress on the HIV/AIDS and STI strategic plan for South Africa. Available at www.doh.gov.za/aids/docs/progress.html. Accessed 1 March 2011. [ Links ]

Department of Human Services 2000. Evidence based health promotion: Resources of Planning. No.2. Adolescent Health. Melbourne: Health Development Section, Department of Human Services. [ Links ]

De Vos AS 2002. Qualitative data analysis and interpretation. In: AS de Vos, H Strydom, CB Fouche & CSL Delport (eds). Research at Grassroots: for the social sciences and human service professions, 339-355. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Doherty-Poirier M, Munro B & Salmon T 1994. HIV/AIDS related knowledge and attitudes. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 3:227-235. [ Links ]

Ebersöhn L & Eloff I 2002. The black, white and grey of rainbow children coping with HIV/AIDS. Perspectives in education, 20:77-86. [ Links ]

Egan G 2002. The skilled helper. A problem management and opportunity based approach to helping. 7th edn. Florence, KY: Wadsworth Publishing. [ Links ]

Foster G 2002. Beyond education and food: psychosocial well-being of orphans in Africa. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 5:55-62. [ Links ]

Foster G & Williamson J 2000. A review of the current literature on the impact of HIV/AIDS on children in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS, 14:275-284. [ Links ]

Fullan M 1993. Why Teachers Must Become Change Agents. Educational Leadership, 50:1-13. [ Links ]

Goba L 2009. Personal interview: District Coordinator for HIV and AIDS teacher training, Port Elizabeth District. [ Links ]

Gordon G 2008. One finger cannot kill a louse - working with schools on gender, sexuality and HIV in rural Zambia. In: S Aikman, E Unterhalter & T Boler (eds). Gender Equality, HIV and AIDS: A Challenge for the Education Sector. 129-149. Oxford: Oxfam. [ Links ]

Govender P 2004. Erasing the future: the tragedy of Africa's education. The South African Institute of International Affairs. e-Africa, 2:1-9. [ Links ]

Greef M 2005. Information collection: interviewing. In: AS de Vos, H Strydom, CB Fouche, CSL Delport (eds). Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human services professions. 3rd edn. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Hall E, Altman M, Nkomo N, Peltzer K & Zuma Z 2005. Potential attrition in education. The impact of job satisfaction, morale, workload and HIV/AIDS. Cape Town: HSRC. [ Links ]

Harrison A, Smith JA & Myer L 2000. Prevention of HIV/AIDS in South Africa: a review of behaviour change interventions, evidence and options for the future. South African Journal of Science, 96:285-290. [ Links ]

Hepburn A 2002. Increasing primary education access for children in AIDS affected areas. Perspectives in Education, 20:87-98. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch 2005. The less they know, the better: abstinence only HIV/AIDS programs in Uganda. New York: Human Rights Watch. [ Links ]

Kelly MJ 2002. Preventing HIV transmission through education. Perspectives in Education, 20:1-11. [ Links ]

Kirby D, Obasi A & Laris B 2006. The effectiveness of sex education interventions in schools in developing countries. UNAIDS Task Team on Young People: Preventing HIV/AIDS in Young People. New York: UNAIDS. [ Links ]

Krefting L 1991. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45:214-222. [ Links ]

Lee A 2009. Health Promoting Schools: Evidence for a holistic approach to promoting health and improving health literacy. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 7:11-17. [ Links ]

Lewin K & Stuart J 2003. Researching teacher education: new perspectives on practie, performance and policy. Multi-site teacher education research project (MUSTER). Synthesis report. (Education research paper No.49). London: Department for International Development. [ Links ]

McBer H 2000. Research into teacher effectiveness: a model of teacher effectiveness. London: UK Department for Children, Schools and Families. [ Links ]

Monk M 1999. In service for teacher development in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of literature published between 1938-1997. (Education research paper No. 30). London: UK Department for International Development. [ Links ]

Moola N 2006. Whole school development, health promoting schools and inclusive education: making connections. Paper delivered at National Health Promoting Schools Conference, September 14-16, University of the Western Cape, South Africa. [ Links ]

Morrell R & Ouzgane L 2005. African Masculinities: Men in Africa from the Late Nineteenth Century to the Present. New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Oxfam 2000. Education Report. Oxford: Oxfam [ Links ]

Peltzer K & Promtussananon S 2003. Perceived vulnerability to AIDS among rural black South African children: a pilot study. Journal of child and adolescent mental health, 15:65-72. [ Links ]

Pisani E 2008. The wisdom of whores: bureaucrats, brothels and the business of AIDS. London: Granta. [ Links ]

Pridmore P & Yates C 2000. The power of open and distance learning for basic education for health and the environment. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Richter L, Manegold J & Pather R 2004. Family and community interventions for children affected by AIDS. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Robson C 2002. Real World Research: a research primer for social scientists and practitioner-researchers. 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Rowling L 2003. School mental health promotion research: Pushing the boundaries of research paradigms. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 2:2. Available at www.auseinet.com/journal/vol2iss2/rowling.pdf. Accessed 15 September 2010. [ Links ]

Smart R 2003. Policies for orphans and vulnerable children: A Framework for Moving Ahead. Washington, DC: The Policy Project. [ Links ]

Strydom H 2002. Ethical aspects of research in the social sciences and human services professions. In: AS de Vos, H Strydom, CB Fouche & CSL Delport (eds). Research at Grassroots: a primer for the social sciences and human service professions, 62-76. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Subbarao K & Coury D 2004. Reaching out to Africa's orphans: a framework for action. Washington, DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

Tang KC, Nutbeam D, Aldinger C, St Leger L, Bundy D, Hoffmann AM et al. 2009. Schools for health, education and development: A call for action. Health Promotion International, 24:68-77. [ Links ]

Theron LC 2007. The health status of Gauteng and Free State educators affected by the HIV and AIDS pandemic - An introductory qualitative study. African Journal of Aids Research, 6:175-186. [ Links ]

Theron LC 2005. Educator perception of educators' and learners' HIV status with a view to wellness promotion. South African Journal of Education, 25:56-60. [ Links ]

Thorpe M 2005. Learning about HIV/AIDS in schools: does a gender equality approach make a difference? In: S Aikman & E Unterhalter (eds). Beyond Access: Transforming Policy and Practice for Gender Equality in Education.. Oxford: Oxfam GB. [ Links ]

UNAIDS 2008. Sub-saharan Africa: AIDS pandemic update. Regional summary. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization. Geneva: UNAIDS. [ Links ]

UNAIDS 2005. The Role of Education in the Protection, Care and Support of Orphans and Vulnerable Children Living in a World with HIV and AIDS. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/Partnerships/UNFamily/IATT-Education.asp. Accessed 18 September 2010. [ Links ]

UNESCO 2008. EDUCAIDS: framework for action. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Van Laren L & Ismail R 2009. Integrating HIV and AIDS across the curriculum. In: C Mitchell & K Pithouse (eds). Teaching and HIV and AIDS in the South African Classroom. Johannesburg: MacMillan. [ Links ]

Visser M 2004. Addressing the Impact of HIV/AIDS. Mozambique: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Visser-Valfrey M 2004. The impact of individual differences on the willingness of teachers in Mozambique to communicate about HIV/AIDS in schools and communities. PhD Dissertation, Florida: Florida State University. [ Links ]

WHO (World Health Organization) 1995. Expert committee on comprehensive school health education and promotion. World Health Organization: Geneva. [ Links ]

WHO (World Health Organization) 2007. Schools for Health, Education and Development: A Call for Action. World Health Organization: Geneva. [ Links ]

Wood L 2009. Not only a teacher, but an ambassador for HIV & AIDS: facilitating educators to take action in their schools. African Journal of Aids Research, 8:83-92. [ Links ]

Wood L 2004. A Model to Empower Teachers to Equip School-leavers with Life Skills. DEd thesis. Port Elizabeth: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. [ Links ]

Woods NF & Cantazaro M 1998. Nursing Research: Theory and Practice. St Louis: Mosby. [ Links ]

Authors

Lesley Wood is Associate Professor in the Faculty of Education and Head of the Action Research Unit at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. Her research interests focus on HIV and AIDS in education, working to help schools respond to the pandemic and design prevention education.

Linda Goba is a Deputy Chief Education Specialist, managing educator training in HIV and AIDS, Life Skills and Social Planning, and the School Nutrition Programme.