Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.31 n.2 Pretoria Jan. 2011

ARTICLES

Life orientation as experienced by learners: a qualitative study in North-West Province

Anne Jacobs*

ABSTRACT

The learning area Life Orientation (LO) is aimed at educating healthy, responsible young people who are able to live productive lives in the new South African democracy. Effectiveness in this learning area has not yet been proved and there is evidence of some problems in attaining this ideal. In order to give voice to learners, in terms of their views, ideas and comments on LO, focus group interviews with mainly high-school learners were utilized in this study. The results of this qualitative investigation indicate that there are various problems in the practice of LO education. Many learners seem to view LO as unnecessary, boring and irrelevant. Furthermore, this study provides some evidence that LO does not succeed in accomplishing its aims, as laid out in the National Curriculum Statement.

Keywords: learners; Life Orientation; National Curriculum Statement

Introduction

"I basically just see LO as a waste of time, 'cause there, you don't learn anything from it." "Yes, I enjoy LO, 'cause there's lots of fun activities."

Both of these statements were made by South African learners who were asked whether or not they liked LO. These two quotes provide a summary of the current debate around LO. Many people are of the opinion that it holds vast potential, others view it as very negative. This holds true for teachers and learners, as well as researchers.

The learning area Life Orientation forms part of the life skills faction, which is popular today in many countries and is often propagated and implemented in educational settings, for example, by the World Health Organisation (World Health Organisation, 1999; Pan-American Health Organisation, 2000; 2001). Increasing effort is currently being devoted to the development of life skills programmes especially in view of the disturbing level of risk behaviours displayed by children and adolescents (Magnani, MacIntyre, Karim, Brown & Hutchinson, 2005:289; Reddy, James, Sewpaul, Koopman, Funani, Sifunda, Josie, Masuka, Kambaran & Omardien, 2010).

Life Orientation is aimed at developing and engaging learners in personal, psychological, neuro-cognitive, motor, physical, moral, spiritual, cultural and socio-economic areas, so that they can achieve their full potential in the new democracy of South Africa (Department of Education, 2002; 2003:9). This learning area is furthermore intended to promote social justice, human rights, and inclusiveness, as well as a healthy environment (Department of Education, 2003b:5).

Even though LO sounds promising in theory it has become apparent that there are many problems in the practical implementation thereof. It is therefore doubtful whether LO is always effective (Prinsloo, 2007:155ff; Christiaans, 2006). In addition to this, scant research has been done regarding the assessment of effectiveness of Life Orientation. One aim of a study done by Prinsloo (2007) was to determine and understand the experiences and perspectives of LO teachers (Prinsloo, 2007:155f). In this study most teachers felt that the effect of the LO teaching did not last. It also appears that teachers do not feel they have been sufficiently trained and, given the fact that often teachers have to teach LO without receiving any, or very little, training, effectiveness becomes questionable (Rooth, 2005:237f, 271; Prinsloo, 2007; Jenkins, 2007:93ff; Christiaans, 2005:133; Van Deventer, 2009:128). Even though some studies assume, at least to an extent, that LO is effective or acknowledge the significance of LO (Theron & Dalzell, 2006; Rooth, 2005) little evidence could be found which proves that LO achieves the aims as set forth in the National Curriculum Statement. A study by Rooth (2005) however pointed out that there were teachers who feel that learners benefited from LO. It nevertheless needs to be noted here that hardly any studies have been conducted with the aim of listening to the voices of the learners and their perceptions of and experiences with LO. Only one study, by Theron (2008), considered the voices of Grade 9 learners. Interestingly and contrary to some of the above studies, this study found that Grade 9 learners in general were very positive about LO.

Generally, it appears that there are a lot of good intentions with the implementation of LO as set forth in the National Curriculum Statement and by other authors (Ngwena, 2003; Department of Education, 2002; 2003). The Revised National Curriculum Statement (2002) gives the following purpose for teaching Life Orientation in Grades R to 9:

"The Life Orientation Learning Area aims to empower learners to use their talents to achieve their full physical, intellectual, personal, emotional and social potential ..." (Department of Education, 2002).

Without doubt this purpose is commendable. The question however remains whether or not it is achieved in practice. The aim of this article is therefore to shed light on the practice of LO as perceived by learners. It is important to listen to the voices of the learners as they are the object of LO. They can provide unique insights and their opinions and experiences can shed light on the current practice and effectiveness of LO.

Research design

Due to the nature of the research topic a qualitative design was chosen. This is the case because there is scant research on the effectiveness of LO and on the implementation and validation of LO. This study is therefore a situation analysis so that recommendations regarding the improvement of the practice of LO can be made. As the nature of the study did not fit with any other specific qualitative design a basic qualitative study design was used, as described by Merriam (2009:23): "Researchers conducting a basic qualitative study would be interested in (1) how people interpret their experiences, (2) how they construct their worlds and (3) what meaning they attribute to their experiences". In this study it is therefore important to consider how learners interpret their experience of LO.

As the researcher is an instrument in qualitative research and is very much part of the whole research process and usually holds certain assumptions (Hanson, Creswell, Plano Clark, Petska & Creswell, 2005; West, 2009) some comments need to be made concerning the researcher's position. She is a white female, brought up in Europe, who has been living in South Africa for more than a decade. The research, which was carried out after extensive observation in the field, was conducted from a realist perspective.

Problem statement

The aim of this research was to determine what the perceptions of learners were regarding their experience of LO in order to make recommendations for improving the practice of LO.

Data collection and analysis

In this study focus group interviews (n= 18), with two to nine participants per group, were conducted. There are various advantages to focus group interviews, such as the fact that the amount and range of data are increased by collecting from several people at the same time and the fact that quality control occurs as the participants talk together and stimulate each other (Robson, 2003:284f). Such interviews are often very spontaneous (Johnson & Turner, 2003: 308). Focus group interviews were considered to be suitable for this study, firstly because learners tend to be shy when approached alone; putting them in groups is more likely to make them feel comfortable so that they will feel free to speak. Secondly, focus group interviews leave room for discussion, which suits the explorative nature of this study.

Except for three interviews, all learners were high-school learners. The main questions guiding the interview were the following:

• What do you learn in LO?

• Do you enjoy the subject? Do you in general feel positive or negative about it? Why?

• Does LO help you in daily living?

• If you could decide on topics and activities in LO what would you do?

In the majority of interviews (12) no teacher was present. However if a teacher was present it was not the LO teacher. It was assumed that learners would feel more free to express their honest opinions without a (LO) teacher being present. In some cases where learners were SeTswana-speaking, a translator was present too, in order to help where the learners had trouble understanding or expressing themselves in English. In most cases the interviews took place in an informal venue (e.g. an empty classroom, outside). No specific time was scheduled as the researcher did not want to interfere with school routine.

The computer program Atlas Ti. was used for analysis of the responses. The responses were coded inductively (with no pre-determined categories or themes) and themes were identified. Practically this meant that the researcher read the responses several times in order to be able to identify the categories which emerged from the responses. The analysis was guided by the four questions, which functioned as a framework for the identification of themes. This, however, did not mean that a response given under one question was not used for another, if it was applicable.

Sampling of participants

Convenience sampling was used to find participants (62) for the focus group interviews, which meant selecting respondents from eight schools in North-West Province, South Africa, that were easily accessible (Robson, 2003:265). The schools included former Model-C schools as well as township schools. All racial groups except coloureds were represented. This was not intended, but there were no coloureds within the groups of learners assigned to the researcher by the school teachers or principals. Altogether 15 interviews were conducted in English, three in Afrikaans. The majority of learners were either SeTswana- or SeSotho-speaking (50), six were English-speaking and six Afrikaans-speaking. Altogehter 49 male learners and 13 female learners participated in the interviews. Learners were in Grades 7 to 12. Focus group interviews were conducted until data saturation was achieved.

Ethical considerations

The ethics committee of the university, under whose auspices the investigation was conducted, approved of the research. The Department of Education as well as the principals gave their permission for the research to be conducted. All participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time from the interviews if they so wished.

Findings

In the following section the interviews conducted with the learners are discussed. As four basic questions were asked the responses of the learners will be discussed under four headings, namely, the content of LO, perceived enjoyment of LO, application of LO to life, and suggestions concerning LO by learners.

The content of LO

This question (What do you learn in LO?) attempted to encourage the learners to talk about LO. It was supposed they would name the topics they covered in class. This, for example, could show whether according to the learners certain topics were often repeated. The aim was also to see whether learners would mention topics or contents from all four or five learning outcomes as stated in the National Curriculum Statement.

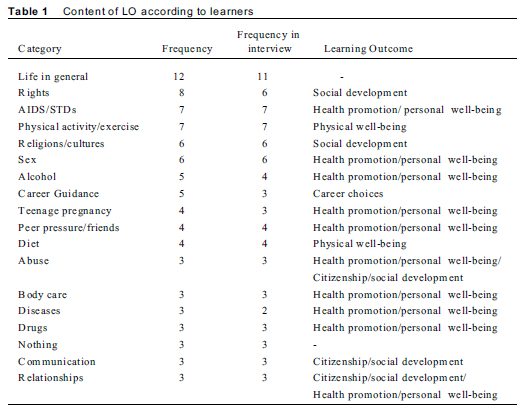

The responses of the learners are summarised in Table 1. Their answers to the question were placed into various categories (first column). These were ordered according to frequency (number of times this topic was mentioned - second column). The third column indicates in how many interviews the specific topic was mentioned. If the numbers in the middle two columns differ, this means there was more than one learner in at least one interview who mentioned the specific topic. In the last column the categories are matched with one of the four Learning Outcomes of LO. As the Learning Outcomes differ slightly in the FET phase (four Learning Outcomes) and the Senior Phase (five Learning Outcomes), they have been summarised. The Learning Outcomes Health Promotion and Personal Well-being from the Senior Phase have been combined. A discussion of the different categories follows.

Except for two of the categories ('life in general' and 'nothing'), all other categories mention an aspect or topic covered in LO. Only 'life in general' was mentioned in the majority of interviews (67%). A possible explanation here is that the learners probably mentioned topics which they had recently dealt with, which have been repeated the most or which made the biggest impression on them. Not all of them would necessarily have reflected back in order to remember all the topics they had already covered in LO. However, it is also possible that often certain topics were not covered in LO classes.

The category with the highest frequency was called 'life in general', which does not mention a specific topic or aspect. These answers were very vague or tried to give a summary of LO. The following is an example from this category:

"So basically LO teaches us about life, things that happen in our lives, and stuff like that." The answers in this category usually gave a broad and correct, but ill defined, idea of Life Orientation, which could possibly mean that learners themselves are not clear on the purpose and content of LO.

The second category in which learners did not mention a specific topic was called 'nothing'. Three learners in three different interviews claimed that they had basically learned nothing in LO. In one interview a learner said:

"Oh, to be precise, we learned nothing."

His classmate then qualified the statement more and added:

"Things we learned, were things that we knew ourselves. Its just that they were just confirming it. Some of it, like, they just came up with their own theories. But I don't think it helped us a lot."

These examples show that some learners thought LO was a waste of time, as nothing new was learned. This also became clear in other interviews, where learners said that they hardly did any work at all. It raises concern that some learners claim that LO serves no purpose at all. This can be compared with results from Theron and Dalzell (2006) who found that Grade 9 learners indicated that the content taught in LO does in many instances not correspond with their expressed needs.

The next categories indicated in Table 1 all deal with a specific aspect of LO, as discussed in the following sections:

The topic mentioned most often was the one of 'rights'. Interestingly only two learners mentioned rights in connection with responsibilities. It therefore appears that human rights play a very important role in learners' minds, while responsibilities seem to be divorced from rights in the minds of learners.

Even though AIDS/STDs, sex, teenage pregnancies, and abuse were put into different categories, they could, however, be summarised into one called sexual health. If taken as one category, this category was mentioned in 10 interviews.

When considering the frequency of the Learning Outcomes it is very clear that Health Promotion/Personal Development featured most often (10 times), compared to Social Development (five times), Physical Development and Movement (twice) and Career choices (once).

The other categories will not be discussed further as the learners generally did not answer in full sentences, but rather listed different topics, without detailed description. The question discussed in the following section endeavoured to measure the extent to which learners like or enjoy LO.

Perceived enjoyment of LO

The questions in this section (Do you enjoy the subject? Do you in general feel positive or negative about it? Why?) could potentially reveal the true feelings of learners concerning LO. The section was, however, complicated by the fact that the learners seemed to want to tell the researcher what they thought she would like to hear. It appeared that the learners thought they had to be positive. In some interviews they were very positive in the beginning, however later on in the interview it became evident that many actually had a problem with LO, as will be shown later. A number of learners tried to sound positive, while actually making clear that they considered the subject a waste of time. In general it was difficult to come to conclusive findings in this matter. The learners from the previously disadvantaged schools were by and large more positive about LO than the learners from other schools. The three interviews done in three Grade 7 classes all showed that the learners liked LO (with one exception).

A number of learners in the previously disadvantaged schools were positive. Some said LO taught them skills which they did not learn elsewhere:

"All I can say about LO is that all the things that they say, LO teaches us different kind of behaviours of different kinds of peoples. So that if a persons[sic] does this, you must do this in order not to hurt them. We learn about understanding other peoples feelings."

One aspect concerning learners from previously disadvantaged schools emerged clearly. Even though learners were positive about the subject it was not evident that they applied what they learned to their lives, which is a concern also mentioned by Prinsloo (2007:165f). Evidence of this is, for example, where a girl stated in an interview that many learners did not like LO because they were engaging in the very risk behaviours they were advised not to be involved in. In the following interview that was conducted (at the same school) all of the learners claimed that they liked LO, but many of them gave the impression that they were actually the ones engaging in risk behaviours. Here it has to be taken into account that Africans tend to stand together as a group trying to please the other person in authority (in this case the researcher) (cf. Friedenthal & Kavanaugh, 2007:19) and might therefore not be truthful. When learners were asked if their peers liked the subject they usually stated that there were those who dislike LO. In at least three interviews the learners said it was the majority who did not like the subject. This supports the possibility that many learners did not reveal their true perceptions about LO.

In the following section the negative responses regarding LO will be discussed briefly. There were learners who claimed that the teaching was done very poorly. Some complained that hardly any teaching was taking place, while others said that the teacher was very boring:

"Uhm, mam, honestly it depends on what we are doing for the day. Honestly, most of the time a lot of the teachers aren't even so enthusiastic about this subject. From them talking so boring, and everything just not clicking, mam ... and then all of that together just makes you negative about the subject. That's all I have to say."

This example confirms that there is a problem regarding the teaching of LO.

In addition to this there were those learners who said that LO to them is a waste of time. This kind of response came mainly from former Model-C schools. Many learners claimed that they had hardly learned anything:

"To me this feels like a lot of nonsense, because it seems to me that this subject is just there for children who live in rural areas who don't really know how to behave, and who don't know there are people who are different from them, who don't know about hygiene and so on. For me it is actually a lot of unnecessary nonsense, because we don't learn much."

Here it can be mentioned that a few learners (in two interviews) stated that their parents taught them the skills and knowledge covered in LO, as can be seen in the following quotes:

"Alright I'll go first, I really don't like the subject 'cause I, believe that LO or life skills is something that your parents can teach you, if you don't have parents then I suppose it would benefit you a lot, but since I do have parents I think I learn more from them than from..."

"Uhm, I would say it feels to me as if LO was just put in to fill the parents' place in the child's life."

On the other hand it seemed that learners from previously disadvantaged schools disagreed; to them LO was more acceptable as the parents did not seem to teach the children about basic matters of life (cf. Prinsloo, 2007:162).

There was quite a big group of learners who seemed to like the subject for various reasons which did not have to do with the content or method of teaching LO. In one interview the learners were mostly positive about LO until the end, when asked if they would like to add something. One learner said "It sucks". When asked why he made contradictory statements, another learner explained that the learner, who made the statement, liked LO because he could chat with the girls in class. This then again raised some questions concerning the teaching, whether learners were allowed to visit in class.

Then there were those learners who were positive about LO, repeatedly. However, they were unable to even give a reason.

"Me mam, I do like LO - a lot, mam. Last year I used to pass LO flying colours, this year ... but it's positive."

In one of the cases where an unqualified positive response was given, the learners had just been smoking dagga (as observed by the teacher on duty):

"Yes, mam ... I like LO. LO is a good subject."

The fact that children were smoking dagga on school grounds was alarming. And it certainly is a contradiction that those learners claimed to like LO and had just smoked dagga. This can count as evidence that LO is not always effective in helping learners change (cf. Prinsloo, 2007:161; 165). This can certainly also serve as an indication of the seriousness of the problems at high schools and among young people in general (cf. Coetzee & Underhay, 2003; Reddy, James, Sewpaul, Koopman, Funani, Sifunda, Josie, Masuka, Kambaran & Omardien, 2010).

Finally there were a number of learners (in four interviews) who felt positive (to an extent) about LO, simply because it was a period where they were able to relax, do homework, or where they simply had a free period:

"I do enjoy it, because most of the time you've got a free period. We go outside and we play..."

"You can always do your homework in there. It's like a flexi-period."

This matter raises concern as well. It appeared to be quite common that LO was not taken seriously by teachers and as a result it was not seen as crucial by learners either.

After the negative responses, the positive responses are now considered. Thirteen learners said that they liked LO because it taught them something in general. However, on closer examination, the answers were not very conclusive. For example:

"Because ... uuhh ... Cause you learn things, you learn new things."

These statements say very little. Other learners said they felt positive about LO because of a specific aspect they were taught:

"Firstly, I didn't know how to deal with stress, and uhm, I didn't know how to use my rights, I used to think like when my parents yell at me ... my parents have to obey their rights. And they told me how to use my rights."

"I like it because they tell you about your life. To be free and not to have sex, when you're still young."

In conclusion, it is evident that this question provided no clear answers. Even though learners were encouraged to elaborate throughout the interviews many answers were very vague. There was no single topic which was mentioned a lot. Results indicate that some learners seemed to appreciate LO, whereas others viewed it as a "waste of time". Teaching practice appears to be a problem as in many cases the subject is not taken seriously by learners or teachers (cf. Prinsloo, 2007:161; 163; Van Deventer, 2009:128).

Application of LO to life

The third question of the interview (Does LO help you in daily living?) examined whether or not learners found LO to be applicable to their daily lives, as this is what LO is intended to do. The only aspect on applicability which was mentioned four times was that of exercise:

"Like, ma'am, for instance, exercise, ma'am. To stay in shape."

It is evident that a number of learners saw the physical exercise component of LO as positive. All other responses that were given regarding applicability did not occur often. Two examples of those are the following:

"Honestly what I've learned most about LO, is how to eat, your diet skills: what to eat and what not to eat."

"I would say in a way a bit maybe, because what we were doing this year, with career guidance, it enlarged your thinking to see what possibilities of study there are."

The results show that what was stated as positive were career guidance and physical exercise. Theron and Dalzell (2006:401) also found that learners placed a high value on the importance of career guidance. In general many learners from the previously disadvantaged schools were more positive about the value and applicability of LO than learners in former Model-C schools.

Suggestions concerning LO by the learners

In this section the question (If you could decide on topics and activities in LO what would you do?) was intended to encourage the learners to say what they felt should be the content and practice in LO. Four learners said they would keep it as it is. Not many things were mentioned by a majority of learners. In five interviews learners suggested that more physical activities should be done in LO:

"Ma'am, maybe things like more activities outside. Because most of the children today, they just sit in front of the TV and play computer and all these things, but maybe more activities outside will help."

It is possible that learners simply enjoy the physical exercise, however, it has to be considered that learners might say this simply because they do not like the theoretical part of LO. Another topic mentioned by five learners is that LO should be taken more seriously:

"And I would say that the subject should be treated like maths and science, that it is treated more intensively and that the teachers take it seriously, because the attitude of the teachers must also be positive."

Learners in seven interviews suggested that LO should be more realistic as well as be taken more seriously. Even though only mentioned explicitly seven times, this featured in other interviews and questions, not as a suggestion, but as remarks: for example, about the lack of 'real issues' or about the perception that the way of teaching was too far removed from reality and should be improved:

"Honestly, they should study the youth of today, ma'am. And start realising what our interests are, ma'am, and start to talk to us about our life and what we do."

In four interviews learners mentioned the topic of sex education. Some felt that there was too much focus on this topic:

"Ya, and they don't have to take us through every step of doing the thing wrong. They can just tell us in general, like don't do rape and this is why. Instead we have to learn about every type of rape there is and all that stuff ... it's really bad, ma'am."

Other suggestions made by learners concerning the improvement of LO were, for example, help with getting a licence, addressing spiritual/religious things, talking about emotions and learning manners. Some learners mentioned topics they think the teacher should talk about. Other learners mentioned the same topics as the ones they are supposed to be taught in LO (according to the National Curriculum Statement) such as rights, resilience, preparing for the future, and respect. This raises the question whether some teachers did not cover all prescribed topics.

Discussion

The first result regarding LO is the fact that there seemed to be a consistently observed discrepancy between theory and practice. This emerges quite clearly when considering the documents published by the Department of Education (2002; 2003; 2003b; 2008; 2008c) regarding LO and the information derived from the interviews with the learners on the practical exigencies in LO instruction as encountered in the actual schools.

The National Curriculum Statement (Department of Education, 2002; 2003) clearly envisions a learner who will acquire actual skills, attitudes, knowledge and values in LO to be able to develop his or her full potential in a holistic manner also with the aim of making 'good' decisions regarding his or her own health and the environment. LO is also specifically intended to help learners face and cope with problems, such as drug abuse, AIDS, peer pressure, and STDs as well as societal issues and problems such as career choices, work ethic, productivity, crime, and corruption. The assessment standards in the National Curriculum Statement (2002; 2003) assert that learners are expected to be able to solve or at least manage these problems in constructive ways. The results of this study show that learners do not always seem to believe that LO really does achieve these aims.

The ideals concerning the envisaged learners as described in the National Curriculum Statement appeared to be divorced from the type of learners that actually emerged from the results of this research. The envisaged learner as mentioned in the National Curriculum Statement from Grades R-9 (Department of Education, 2003:3) is "one who will act in the interests of a society based on respect for democracy, equality, human dignity, life and social justice. The curriculum seeks to create a lifelong learner who is confident and independent, literate, numerate, multi-skilled, compassionate ..." Even though LO cannot solely be blamed for the fact that many young people today do not conform to this ideal, it remains a fact that drugs, alcohol abuse, sexual abuse, and unhealthy behaviour are still rampant in our society (Reddy et al., 2010).

Another important finding of this research is that there is some evidence that LO as a subject may not effect as much meaningful change in the attitudes and behaviours of the learners as was anticipated. The aim of this study was not to determine how effective LO is, but it is nonetheless a theme that clearly emerged. Listening to the learners in the interviews, as well as judging from observations in schools, it became clear that the authors of the Curriculum Statements (Department of Education, 2002; 2003) seemed to be overly optimistic and simplistically dismissed some of the debilitating realities in schools and among young people in general. LO instruction did not always appear to be even moderately effective in changing learners in even some of these ways (cf. Prinsloo, 2007). Many learners felt that they learned nothing new. The finding that LO was often not taken seriously probably contributes to this state of affairs and is also confirmed by Rooth (2005:68f). It was well attested in the interviews that learners often saw LO as a 'free' period, or a time where they could socialise with their friends. It seemed as if very little measurable written seat-work was done. Especially learners from former Model-C schools tended to make negative remarks concerning LO throughout the interviews. Interestingly learners from previously disadvantaged schools tended to be more positive than learners from Model-C schools. This would at least support the study conducted by Theron (2008) to an extent, who found that Grade 9 township learners value LO. This finding is worthy of further exploration. It will be important to listen to more learners from different cultures to see whether this finding is confirmed. It might be that learners from different cultures have different LO needs, a similar suggestion also made by Theron (2008: 62).

There also appears to be the perception that LO focuses a lot on Health Promotion and Personal Development, such as AIDS and related topics. It appeared that learners felt these topics were "overtaught", which does not seem to agree with the study by Theron (2008), where learners appeared to value the time spent on AIDS and related topics.

A very crucial point needs to be made here. It appears that little or no research has been done that examines the actual successes of LO. It has to be remembered that the perceptions of learners as investigated by this study as well as the study by Theron (2008) cannot serve as the only valid evidence for or against the effectiveness of LO. In the future it will become important that research is conducted that measures the actual success of LO, especially in terms of long-term effects. Young people often tend to be unrealistic in their perceptions and opinions and their perceptions and ideas can therefore not be the only measurement for the effectiveness of LO. An example in case here is the fact that 99% of young people in South Africa consider their health to be good or average (Morrow, Panday & Richter, 2005:23). However, considering the large numbers of young people who for example are afflicted by AIDS, this is highly unrealistic.

Limitations

There are some limitations regarding this study that must be taken into account: Due to the fact. that this study was qualitative in nature the number of respondents was very small. In addition to that the interviews were conducted in only one province of South Africa. Therefore caution is advised when making generalisations for the whole of South Africa.

Recommendations

More research should be done regarding the perceived problems concerning LO (which became apparent in this study) in order to ultimately improve the practice of LO. In addition to that similar research projects should be conducted in the other provinces of South Africa in order to establish whether or not the trends described in this article also hold true for the other provinces. The following recommendations are therefore based on the practice of LO as perceived by learners in North-West Province:

• The apparent weaknesses of LO practice need to be seriously considered. This includes ineffectiveness, negative attitudes by both learners and teachers as well as the fact that the theory of the National Curriculum Statement and practice are far removed from each other.

• Life Orientation teachers need to take responsibility for LO, in other words, they need to start taking this learning area/subject seriously, thereby instilling in the learners an appreciation for LO.

• Learners' opinions should be taken into account when deciding on themes. It seems to be very important that the learners have a chance to let their voices be heard in this matter.

• Research must be conducted concerning the effectiveness of LO. Ways need to be found to measure the long term effects of LO.

• Another research focus needs to be an investigation into the different LO needs of learners from different cultures.

References

Christiaans DJ 2006. Empowering teachers to implement the Life Orientation learning area in the Senior Phase of the General Education and Training Band. MEd dissertation. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Coetzee M & Underhay C 2003. Gesondheidsrisikogedrag by adolessente van verskillende ouderdomme. S.A. Tydskrif vir Navorsing in Sport, Liggamlike Opvoedkunde en Ontspanning, 25:27. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2002. Revised national curriculum statement. Grades: R-9. Life Orientation. Capetown: FormeSet Printers. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2003. Revised national curriculum statement. Grades: 10-12. Life Orientation. Capetown: FormeSet Printers. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2003b. Revised national curriculum statement. Grades: R-9: teacher's guide for the development of learning programmes policy guidelines: Life Orientation. Capetown: FormeSet Printers. [ Links ]

Department of Education. 2008. National curriculum statement. Grades: 10-12. Learning programme guidelines. Life Orientation. Available at http://www.thutong.doe.gov.za/ResourceDownload.aspx?id=39835 Accessed 10 November 2008. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2008c. National curriculum statement: Grades 10-12 (general) learning programme guidelines Life Orientation. Available at www.thutong.doe.gov.za/ResourceDownload.aspx?id=39835 Accessed 10 November 2008. [ Links ]

Friedenthal L & Kavanaugh D 2007. Religions of Africa. Philadelphia: Mason Crest Publishers. [ Links ]

Hanson WE, Creswell JW, Plano Kelly VL, Petska S & Creswell JD 2005. Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52:224. [ Links ]

Jenkins MW 2007. Curriculum recontextualising using gardens for the health promotion in the Life Orientation learning area of the senior phase. MEd dissertation. Grahamstown: Rhodes University. [ Links ]

Johnson B & Turner LA 2003. Data collection strategies in mixed methods research. In: A Tashakkori & C Teddlie (eds). Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioural research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Merriam SB 2009. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Morrow S, Panday S & Richter L 2005. Young people in South Africa in 2005. Where we're at and where we're going. Halfway House: Umsobomvu Youth Fund. [ Links ]

Ngwena C 2003. AIDS in schools: A human rights perspective on parameters for sexuality education. Acta Academica, 35:184. [ Links ]

Pan American Health Organization 2000. Adopting the life skills approach. Available at http://www.paho.org/English/DBI/SP579/SP579_05.pdf Accessed 2 March 2006. [ Links ]

Pan American Health Organization 2001. Life skills approach to child and adolescent healthy human development. Available at http://www.paho.org/English/HPP/HPF/ADOL/Lifeskills.pdf Accessed 3 April 2006. [ Links ]

Prinsloo E 2007. Implementation of Life Orientation programmes in the new curriculum in South African schools: Perceptions of principals and Life Orientation teachers. South African Journal of Education, 27:155. [ Links ]

Reddy SP, James S, Sewpaul R, Koopman F, Funani NI, Sifunda S, Josie J, Masuka P, Kambaran NS, Omardien RG 2010. Umthente Uhlaba Usamila - The South African Youth Risk Behaviour Survey 2008. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council. [ Links ]

Robson C 2003. Real world research. 2nd edn. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Rooth E 2005. An investigation of the status and practice of Life Orientation in South African schools in two provinces. PhD thesis. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Theron LC & Dalzell C 2006. The specific life orientation needs of Grade 9 learners in the Vaal Triangle region. South African Journal of Education, 26:397. [ Links ]

Theron LC 2008. The Batsha Life Orientation study - An appraisal by Grade 9 learners living in townships. Education as Change, 12:45. [ Links ]

Van Deventer K 2009. Perspectives of teachers on the implementation of Life Orientation in grades R-11 from selected Western Cape schools. South African Journal of Education, 29:127. [ Links ]

West W 2009. Research report: Situating the researcher in qualitative psychotherapy research around spirituality. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 22:187. [ Links ]

World Health Organization 1999. Partners in life skills education: conclusions from a United Nations Inter-Agency meeting. Available at http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/30.pdf Accessed 9 November 2009. [ Links ]

Author

Anne Jacobs (née Karstens) is Research Fellow in the School of Philosophy at the North-West University. Her research interests include epistemology, the practice of life orientation in South African schools, spirituality and education, and philosophy of education.