Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.31 no.2 Pretoria Jan. 2011

ARTICLES

Exploring safety in township secondary schools in the Free State province

M G Masitsa*

ABSTRACT

Research overwhelmingly suggests that effective teaching and learning can occur only in a safe and secure school environment. However, despite the plethora of laws and acts protecting teachers and learners in South African schools, scores of them are still unsafe. This study examines the safety of teachers and learners in township secondary schools in the Free State province, South Africa. The sample of study consisted of 396 teachers who were randomly selected from 44 township secondary schools across the province. The sample completed a questionnaire based on the safety of teachers and learners in their schools. Prior to completion, the questionnaire was tested for reliability using the Cronbach alpha coefficient and it was found to have a reliability score of .885, indicating an acceptable reliability coefficient. The questionnaire was computer analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Primer Version 12. The results of the analysis revealed that both teachers and learners are not safe in their schools, either during or after school hours. The causes of a lack of safety in these schools reside within and without the schools, implying that learners are sometimes the culprits. The study concludes with recommendations on addressing the problem.

Keywords: crime; exploration; school safety; teachers' and learners' rights; township secondary schools; violence

Introduction

The question of safety in schools and the child's right to receive education, the world over, have been under the spotlight for some years. Thro (2006:66) states that it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he/she is denied the opportunity of an education. He contends that the opportunity to pursue an education, particularly quality education, is meaningless unless the student is able to pursue his/her educational rights in an environment that is both safe and secure. According to Christie, Butler and Potterton (2007: 210) the purposes of schooling, which can be achieved only in a peaceful school environment, are: to provide an environment where teaching and learning can take place; to prepare people for the world of work, nation-building and citizenship; to teach the values of society; and the development of the individual. In South Africa the right to receive education is guaranteed in the Constitution, implying that it has to be respected.

Prinsloo (2005:5) states that the South African Constitution and legislation make provision for the protection of the rights and safety of learners in schools. In addition, South Africa is a signatory to the Convention of the Rights of the child adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1989, which makes it obligatory for members to pass laws and enforce measures to protect the child from all forms of violence, abuse, neglect, maltreatment or exploitation. Section 28(1) of the South African Constitution (hereafter, the Constitution), (RSA, 1996a) stipulates that: "every child has the right to be protected from, among others, neglect, abuse or degradation". Thus, learners' rights to a safe and secure school environment are protected by law. Taking cognisance of what is stated in the foregoing paragraphs this study explores the safety of the school environment in township schools in the Free State Province.

Statement of the problem and aim

Research overwhelmingly suggests that effective teaching and learning can occur only in a safe and secure school environment which is every community's desire for its children (Xaba, 2006:565; Pinsloo, 2005:10; Dilion, 2007:10; Trump, 2008:240). However, there is a deep-rooted culture of violence in schools that has been cultivated in different ways over many years, thus making schools unsafe and insecure. The following media reports bear testimony to this assertion: "A high school pupil was robbed and killed by a fellow pupil, and a teacher was robbed at gun point in front of a class" (Kuppan, 2008:1). "A gang of four girls, one armed with a knife have been robbing their school mates of their money as they get off taxis and buses" (Kotlolo & Ratsatsi, 2009:1; Hosken, 2009:1). "Security guard shot and killed in cold blood by two robbers who robbed a nursery school" (Carstens, 2009:1). "Schools use private firms for security after a spate of attacks by armed robbers targeting parents dropping off and fetching their children" (Hosken & Bailey, 2009:1). "A Grade 8 pupil at Zamazulu high school died after being accidentally shot with his father's gun by a friend in front of the class" (Ngobese, 2009:1). "Police are searching for a man who opened fire at his child's school, shooting the principal and injuring a 12-year-old pupil" (Skade, 2009:1). Diverse incidents are provided to demonstrate the scope of the incidents causing a lack of safety in schools and of the modus operandi of the perpetrators.

The above reported incidents project only the aspect of physical safety in schools, namely, violence and crime, which is the focus of this study. The other aspect of safety focuses on psychological safety. A circumspect analysis of these incidents indicates that schools are not safe and secure and that the perpetrators of violence at schools come from within and without the schools. They include learners, parents of learners and gangs or individuals from the community. They target learners, educators and principals, security guards and learners' parents. These incidents indicate the ease with which learners can go to school armed and how schools are easily accessed by unsafe elements, often with violent and criminal consequences (Xaba, 2006:566). Xaba (2006:566) indicates that township schools are especially vulnerable to unsafe conditions and threats of violence due to, among other things, poor resources, infrastructure and their location. What is common about the incidents under discussion is that they all seem to have occurred in and around schools, and during school hours, which highlights the vulnerability of schools to safety-threatening incidents. Thro (2006:66) holds the view that if learners are subjected to physical violence, to bullying and intimidation and to a culture of illegal drugs, effective learning cannot take place. Trump (2008:66) warns that if learners do not feel safe to learn and teachers do not feel safe to teach, the focus shifts from academic tasks to discipline and personal safety.

Research has shown that when examining the causes of school crime and disruption it is important to take into account demographic factors such as school size, levels of poverty and of neighbourhood crime associated with increased violence. In this regard Khoury-Kassabri, Benbenishty, Astor and Zeira (2004); Gottfredson (1977); Redding and Shalf (2001); Laub and Lauritsen (1998); Mercy and Roseberg (1998) as cited in Nickerson and Martens (2008:230) state that school crime is more apparent in large schools than in small schools; poverty is associated with increased school crime; youth from the inner cities, when compared with those from other communities, are at greater risk of violent behaviour; poverty, population turnover and crime in the surrounding neighbourhood are among the strongest predictors of school violence. Moreover, secondary schools are 13 times more likely to be violent than elementary schools.

Demographic and community factors that influence or impinge on school safety are also found in South African townships as well, where the study was undertaken. Xaba (2006:566) claims that South African township schools are especially vulnerable to unsafe conditions and threats of violence due to, among others things, their location, especially in and around informal settlements. Blaine (2009:1) and the Daily News (2009:1) hold the view that the crisis in South African schools is reflected in the crisis in South African society. Endemic crime and violence in South African society have spilled over into the schools. Netshitahame and Van Vollenhoven (2002:313) found that South African rural schools are situated in high poverty areas and the poverty of their communities has led to countless incidents of vandalism and theft in these schools. Furthermore, drug dealers see schools as an untapped market for their business by selling drugs to learners, thus taking advantage of their curiosity and immaturity (Hosken, 2005:1).

In the light of the foregoing, the aim of this study is to investigate and provide insight into the problems concerning safety experienced by township schools in the Free State. A literature study was undertaken on the issues of safety in schools and an empirical investigation was conducted on the basis of educators' views regarding safety at their schools. The study aims to explore the following research question: What are the safety problems facing teachers and learners in township secondary schools in the Free State?

The phenomenon of school safety

To be safe is to be protected from any form of danger or harm, or to be secure. It is generally accepted that a safe school is a sine qua non for effective teaching and learning (Prinsloo, 2005:10) and that good discipline is the most important characteristic of an effective school. Squelsh (2001:149) and De Waal as cited in Oosthuizen (2005:53) regard safe schools as schools that are physically and psychologically safe and that allow educators, learners and non-educators to work without fearing for their lives. Oosthuizen, Rossouw and De Wet (2004:2) regard good order, discipline, safety, harmony and mutual respect as fundamentals for security. In support of the afore-mentioned authors, Xaba (2006:566) contends that indicators of safety include good discipline, a culture conducive to teaching and learning, professional teacher conduct, and good governance and management practices. A safe school is therefore a place where teachers teach and learners learn, and non-educators work in a warm and welcoming environment, free of intimidation and the fear of violence, ridicule, harassment and humiliation; where everybody is physically and psychologically safe (Squelsh, 2001:138; Oosthuizen, 2005:14).

According to Maslow (Department of Education, 2008:87), human needs can be classified according to five levels of priority. The first and most pressing of these relates to the biological and physical need for survival. This is followed by a requirement for safety or a safe environment. Only once these needs have been addressed, can the process of belongingness, building self-esteem and self-actualisation begin. The preceding discussion not only stresses the value of safety in a school milieu, but confirms the view that education, in the true sense of the word, cannot occur in the absence of safety. Maslow regards safety as the search for security, stability, dependency and protection, as freedom from fear, anxiety and chaos and the need for structure and order. This implies that a person yearns for safety, thus making it an important requirement for survival and an important aspiration of a learner. In short, the adage 'safety first' is appropriately applicable to a school situation.

The learner's right to a safe school milieu

The learner has the right to a safe school milieu which the school should provide. Teachers, by virtue of their profession and by law, are obliged to maintain discipline at school and to act in loco parentis in relation to the leaner. Prisloo (2005:10) states that the functions that educators should fulfil in terms of the common law principle, in loco parentis, include the right to maintain authority and the obligation to exercise caring supervision of the learner. Maithufi (1997: 260-261) explains that there are two sides to the in loco parentis role of educators: the duty of care (the obligation to exercise caring supervision) and the duty to maintain order (the obligation to maintain authority or discipline over the learner). When the child enters the school, the duty of care of the parent or guardian is delegated to the educator or the school. Thus, educators have a legal duty to ensure the safety of learners at school. Ensuring the learner's safety at school is thus the educator's pedagogical and legal function. Oosthuizen et al. (2004:3) state that the law expects the educator to caringly see to the physical, psychological and spiritual well-being of the learner. The law expects him/her as a professionally trained person to fulfil this role with the necessary skill.

In the Bill of Rights discussed in this paragraph, Section 29(1) of the Constitution stipulates that the learner has the right to receive education. The learner's right to receive education implies that the learner has the right to attend school and that this right should be protected. Since education can only take place in a safe and secure school environment, everything possible should be done by the school, the Governing Body and by the Department of Education to ensure that the learner experiences safety at school. Section 12(1) of the Constitution stipulates that everyone has the right to freedom and security which includes: the right not to be treated or punished in a cruel, inhumane or degrading way and the right to be free from all types of violence. Section 24(a) of the Constitution stipulates that everyone has the right to an environment that is not harmful to his/her well-being and to enjoy education in a harmonious and carefree environment. Therefore, the learner's right not to be treated in an inhumane or degrading way, his/her right to be free from all forms of violence and his/her right to enjoy education in a harmonious and carefree environment, imply that he/she should experience safety at school. Section 28(2) of the Constitution stipulates that the best interests of the child are paramount in every matter concerning the child. It is in the best interests of the child to attend school and to receive education. Therefore, a lack of safety at school is not in the best interest of the child because it will make it difficult for him/her to attend school and to receive education.

In order to promote school safety, the regulations for safety measures at public schools, par 4, sub par 2(e), states that no person may enter the school premises while under the influence of drugs or alcohol (Coetzee, 2005:285). Brown (2006) as cited in Coetzee (2005:292) contends that the use of drugs undermines a safe and disciplined environment and that drug testing will make schools safer. Oosthuizen (2003:80) states that educators protect learners through the maintenance of school discipline, because discipline protects the learner against the unruly and undisciplined behaviour of his/her fellow learners, as well as protecting the learner against his/her waywardness.

The teacher's right to a safe school milieu

As with the learner, the teacher has the right to a safe school milieu. In fact, since the learner and the teacher operate in the same school environment, what applies to the learner with regard to safety also applies, mutatis mutandis, to the teacher. It is unequivocal logic that the teacher cannot provide adequate safety and security for the learner if he/she is not safe at school. An unsafe school milieu will, undoubtedly, undermine the teacher's authority and prevent him/her from exercising the right to maintain authority and the obligation to exercise caring supervision of the learner. The Occupational Health and Safety Act, Act 85 of 1993, provides for the health and safety of a person at work (Prinsloo, 2005:5). This applies to the teacher as well. Thus, according to this Act, the teacher is supposed to feel safe and secure at school at all times. Section 14 of this Act stipulates that employees should report unsafe and unhealthy situations to the employer.

As Section 10 of the Constitution (Bill of Rights) stipulates, everyone, including the teacher, has the right to have his/her dignity respected and protected. Insecurity at school may undermine the teacher's right to have his/her dignity respected and protected and this may have a negative impact on his/her in loco parentis status or on his/her right to maintain authority and to exercise caring supervision of the learner. Section 12(1) of the Constitution (Bill of Rights) stipulates that the teacher has the right to the freedom and security of a person which includes being free from all forms of violence. This right implies that the teacher has the right to teach or work in a safe and secure school milieu which is of critical importance because in the absence of such an environment, the teacher will not be able to effectively perform his/her duties and responsibilities. Learners may also not feel safe and secure in a school environment where their teachers are unsafe.

Research design and methodology

Quantitative approach

A quantitative empirical investigation, which can be described as exploratory in nature, was undertaken in this study. The quantitative approach as a data-gathering method is underpinned by a positivistic research paradigm. It follows a numerical method of describing observations or phenomena (Waghid, 2003:42-47). A structured questionnaire was developed and used to gather data from the sample of participants. Data used in this study were quantitatively acquired, recorded and analysed as reflected in the different tables. This was succeeded by the data interpretation leading to the findings, conclusions and recommendations.

Research sample

In order to draw a sample from a wide area of research, this study was conducted in four of five education districts of the Free State province, from each of which 11 secondary schools were selected by means of random sampling based on an address list of Free State schools. The address list used to select a sample did not distinguish specifically between town and township schools, but between types of schools such as public, primary and secondary schools, hospital schools, farm schools, independent schools and schools for the disabled. The researcher selected township schools by making an assumption in terms of the names of the schools on the address list. Upon request for a list of township schools from the Department of Education he was informed that there is no list which separates township schools from other community schools, as this would be discriminatory. He was advised to identify them by employing the method he used. He found that there were approximately 284 primary schools, 153 secondary schools and 136 intermediate and combined schools in townships in the Free State (Free State Department of Education, 2006). The sample in this study consists of 44 township secondary schools. The principals of the selected schools were requested to ask nine educators, who were randomly selected to form the sample for this study, to complete a questionnaire. An obvious shortcoming of this study is that learners, whose experience of school safety may be different from that of educators, were not used as part of the sample. Of the 396 questionnaires distributed, 348 were returned and were suitable for processing, thus realising a response rate of 88%.

Research method

The researcher undertook an exploratory study since no previous research has been done on school safety in the Free State. Prior to this investigation, the researcher was not aware of the nature and extent of the problem of school safety. Therefore, he explored the dimensions of this problem to see whether it is serious enough to justify further in-depth, long-term studies (Jansen in Maree, 2007:11). The research was based on a literature study and a structured questionnaire. Discussions with six principals of secondary schools concerning safety at their schools and a literature review identified items for inclusion in the questionnaire. The aim of the questionnaire was to obtain quantifiable and comparable data. The use of questionnaires was compatible with and appropriate to the aim and purpose of this study as participants were distributed over a wide area. In the questionnaire, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which safety- or lack of safety-related incidents occur at their schools by choosing from five possible answers by using a Likert scale in selecting a response. Data from the questionnaires were computer analysed by a statistician using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Primer Version 12.

Validity and reliability

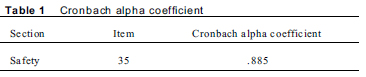

Cronbach's alpha coefficient is a measure of internal consistency showing the degree to which all items in a test measure the same attribute (Huysamen, 1993:125). Santos (1999:2) adds that the higher the score, the more reliable the generated scale. He indicates that 0.7 is an acceptable reliability coefficient, although lower thresholds are sometimes used in the literature. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was calculated for the questionnaire and the results are indicated in Table 1.

Since the Cronbach alpha coefficient average for safety in the secondary schools is .885 and 0.7 indicates an acceptable reliability coefficient, the coefficient is reliable.

To observe reliability and content validity, the questionnaire was structured so that the questions posed were clearly articulated and directed. It was pre-tested on five educators from secondary schools which were not part of the sample schools and thereafter, amendments were made to ensure the simplicity and clarity of some questions, thus making it fully understandable to the participants. To ensure the validity of the responses, the principals who administered the questionnaire explained it and the rationale of the study to the participants, as well as the value of providing correct responses. The questionnaires were completed anonymously to ensure a true reflection of the respondents' views, and principals were requested not to discuss the questionnaires.

Ethical considerations and administration

Permission was obtained from the Free State Department of Education and the principals of the selected schools to use their schools and educators for this study. The questionnaire was submitted to the Department of Education for approval, and an undertaking was made to provide the Department of Education with a copy of the completed research. Assurance in relation to confidentiality and anonymity was discussed with the principals and the participants, and consent for participation was obtained from all participants. The participants' right to withdraw their participation was also discussed. The participants remained anonymous and the information supplied by them was treated confidentially and not linked to their schools.

The researcher distributed the questionnaires to the sample schools in three districts, with a colleague distributing the questionnaires to the sample schools in one district. Guidelines for the completion of the questionnaire were discussed with the principals. Schools were given a week to complete the questionnaires which the principals administered in all the school districts. The researcher and his colleague fetched the completed questionnaires from schools nearby, while questionnaires from the more distant schools were returned by post.

Results

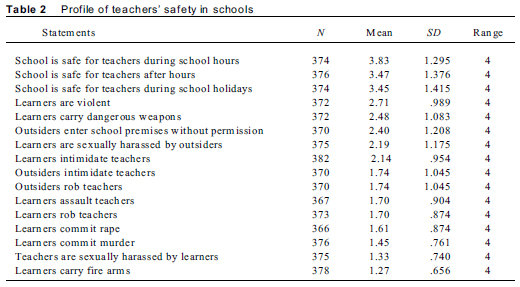

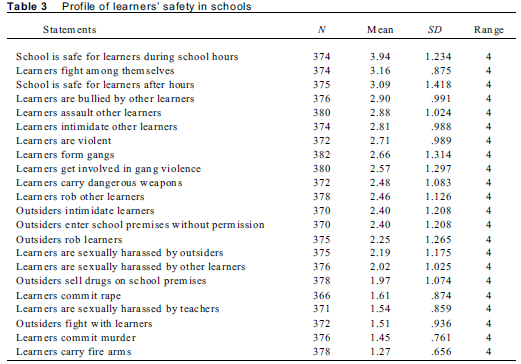

This study investigates the extent to which safety- or lack of safety-related incidents occur at 44 secondary schools in townships. The results will indicate the extent to which learners and teachers are safe or unsafe at these schools. An analysis of the results is presented hereafter. In Tables 2 and 3 the mean scores represent the following alternatives: 1 never, 2 rarely, 3 sometimes, 4 most of the time, and 5 always.

In Table 2, means raging from 1.27 to 1.74 indicate that the participants as a group never experience the incidents. Means raging from 2.14 to 2.71 indicate that the participants as a group rarely experience the incidents. Means raging from 3.45 to 3.83 indicate that the participants as a group sometimes experience the incidents. There are no means indicating that participants experience the incidents most of the time or always.

In Table 3, means raging from 1.27 to 1.97 indicate that the participants as a group never experience the incidents. Means raging from 2.02 to 2.90 indicate that participants as a group rarely experience the incidents. Means raging from 3.09 to 3.94 indicate that participants as a group sometimes experience the incidents. There are no means indicating that participants experience the incidents most of the time or always.

Discussion

Considerable data related to the purpose of this study and gleaned from the questionnaire were analysed and will now be discussed.

Teachers' safety in schools

Incidents concerning teachers' safety such as: school is safe for teachers during school hours; school is safe for teachers after hours; and school is safe for teachers during school holidays are experienced sometimes by the sample of this study, implying that during the said times schools are sometimes, but not all the time, safe for teachers. However, the author argues that when educators are not completely safe they may be precluded from performing their academic and related functions effectively. Teachers rarely experience incidents that threaten their safety, such as: learners are violent; learners carry dangerous weapons; outsiders enter school premises without permission; learners are sexually harassed by outsiders; and learners intimidate teachers; implying that the incidents are very uncommon. Although very uncommon, they need to be prevented from occurring. Incidents such as: outsiders intimidate, rob, and assault teachers; learners rob teachers; learners commit rape and murder; teachers are sexually harassed by learners; and learners carry fire arms, are never experienced by the sample of this study. In general, these findings confirm the findings from the literature that township schools experience safety problems, but the situation regarding the teacher's safety in the Free State is not as critical as portrayed in the literature, and in particular, in the media. This is not strange as the media often report isolated incidents which are not research-based or may report about areas that are seriously affected by a lack of school safety.

Learners' safety in schools

Incidents concerning the learners' safety such as: school is safe for learners during school hours; learners fight among themselves; and the school is safe for learners after hours, are experienced sometimes by the sample of this study. This implies that during the said times, the school is sometimes, but not all the time, safe for learners and that learners sometimes, but not all the time, fight among themselves. To suggest that learners sometimes fight among themselves and that schools are sometimes not safe for learners during and after hours indicates that the learners' safety at these schools is not guaranteed, but is a matter of chance. Scores of township learners live in informal settlements (Xaba, 2006:56) and their homes do not provide an atmosphere conducive to learning. These learners would not be encouraged to study at school after hours because it may not be safe. In addition, although these incidents occur sometimes, they can hinder effective teaching and learning at schools.

Learners rarely experience a lack of safety with incidents such as: learners are bullied, assaulted and intimidated by other learners; learners are violent, form gangs, get involved in gang violence, carry dangerous weapons and rob other learners; outsiders intimidate learners, enter school premises without permission and rob learners; and learners are sexually harassed by outsiders and by other learners. It may be argued that since these incidents are very uncommon, they do not pose a serious danger for the safety of learners at schools. However, although these incidents occur rarely, they must be treated with extreme caution, since apart from having the potential to hamper effective teaching and learning they constitute crime or are serious forms of criminal behaviour. In this sense, their magnitude outweighs by far their frequency of occurrence. Incidents such as: outsiders sell drugs on school premises and fight with learners; learners commit rape, murder and carry fire arms and learners are sexually harassed by teachers are never experienced by the sample of this study. In general, the situation regarding the learners' safety in the Free State is also not as critical as portrayed by the literature, and in particular, by the media. However, the incidents discussed confirm the assertion made in the statement of the problem, based on the literature study, that township schools are not safe and that the perpetrators of crime and violence in these schools come from within and without the schools, thereby complicating matters.

Conclusions

Despite the Constitution and the plethora of laws protecting teachers and learners in South African schools, scores of them are still unsafe. Schools do not only have to deal with common learner misdemeanours, but with learners involved in criminal behaviour at schools, some of which may be injurious to teachers and fellow learners. There are multiple factors that cause the township secondary schools under investigation to be unsafe for both learners and teachers. The fact that the perpetrators of misbehaviour at these schools come from within and without the schools makes the resolution of problems difficult. The nature of some of the incidents that cause a lack of safety in schools should compel stakeholders to find a speedy resolution to the problems before they escalate. It is logical to assume that a lack of safety at these schools has a negative impact on academic performance and defeats the purposes of schooling. Because the learners' and teachers' safety in schools is guaranteed by the Constitution and by law, the state of a lack of safety for teachers and learners at schools implies a transgression of the country's Constitution and laws.

Recommendations

To be effective, the following recommendations should be implemented by all schools situated in the same residential area and should be monitored regularly.

This study has revealed that the state of insecurity in South African township secondary schools needs attention before it spirals out of control. If the learner's right to receive education and the teacher's right and obligation to provide education are to receive any substantive meaning, the Department of Education, as an organ of government and the state, should ensure that schools are safe and secure during and after school hours. The government has the power and resources to provide for school safety. The Department of Education, School Governing Bodies and parents should act swiftly and decisively against a learner (or anyone for that matter), who is disruptive, who engages in violence or who is found guilty of a serious misdemeanour and who places the lives of teachers and/or learners in jeopardy. It is important for parents and teachers to send a strong message to children that home and school are working together to ensure a safe and secure school environment for everyone involved in education (Fritz, 2006:2).

The schools should apply the following safety measures after discussing them with all stakeholders: ensuring that there is proper fencing around the school yard; demarcating the school area as out of bounds to strangers; controlling access to the school during and after school hours; encouraging learners to take responsibility for their part in maintaining school safety by, inter alia, reporting crime, learners who are in possession of drugs or weapons, strangers, suspicious objects inside or outside the school, and anything that poses a threat to learners or the school.

The members of the school governing body should use the powers granted to them by legislation to ensure school safety. Section 18A (2) of the Schools Act (RSA, 1996b) stipulates that the governing body must adopt a code of conduct aimed at establishing a disciplined, peaceful and purposeful school environment. The code of conduct should address aspects related to discipline and the safety of learners; the carrying of dangerous weapons; the use of illegal drugs; and bullying, fighting and harassment at school. Section 20(1) of the Schools Act (RSA, 1996b) grants the governing body power to administer and control the school's property, buildings and grounds. The foregoing entails, inter alia, protecting and guarding all school property and playgrounds; keeping the grounds free of dangerous objects; and maintaining equipment in good working order. Section 5 (1) of the Schools Act (RSA, 1996b) grants the principal power to take such steps as he/she may consider necessary for safeguarding the school premises, as well as protecting the people therein.

Dilion (2007:10) suggests that schools should build a healthy and supportive learning environment by encouraging good behaviour and by explicitly teaching social skills, such as how to listen and communicate and manage and resolve conflict. Teaching learners conflict resolution techniques would equip them with skills to resolve disagreements, deal with bullies and cope with other issues that can spiral out of control if not addressed quickly (Fraser, 2007:49). In addition, the author holds the view that schools should teach, as part of their curriculum, moral values such as respect, responsibility, obedience, honesty and human dignity, as these will inculcate good behaviour in learners.

Nickerson and Martens (2008:240) warn that school-based intervention may only affect violence (or crime) in a limited way, underscoring the need for community partnerships to tackle this complex and multifaceted issue. Kassiem (2008:1) concurs that if violence or crime (especially when it has become endemic) is not stopped in communities, it will be impossible to stop in schools. This holds true because schools are microcosms of their communities. It is reasonable to assume that each community knows its learners and the threats they pose (Darden, 2006:54). The schools, parents, community and the police should hold regular meetings where strategies of addressing community and school safety are discussed. The police should take decisive action, as this is their responsibility, against those who pose a safety threat to schools and the community, as well as against the perpetrators of crime in general. The regulations for safety measures at public schools 4 (3) (RSA, 1996b) stipulate that a police official or the principal or delegate may, without a warrant, search any public school premises for illegal drugs and dangerous objects, search any person on public school premises and seize any dangerous objects or illegal drugs present on public school premises. The police are, in actual fact, the custodians of the law and the Constitution and should conduct intermittent searches of learners particularly in trouble-prone schools to look for drugs, weapons and other illegal items.

Concluding remarks

This study has revealed convincing research evidence indicating that despite numerous laws protecting the rights of teachers and learners in South African schools, scores of township secondary schools are still unsafe. Since research has found that a lack of, or poor school safety, militates against effective teaching and learning, it may be argued that one factor that contributes to poor academic performance in township secondary schools is this lack of, or poor safety. Factors contributing to poor school safety have been found to come from within and without the schools, thus making it imperative that the problem is addressed by all community stakeholders. The study has yielded recommendations on ways to address the problem before it reaches crisis proportions.

References

Blaine S 2009. Street violence reflects school crisis. Business Day, 27 May. [ Links ]

Carstens E 2009. Vier keer getref nadat boewe sê hulle is daar om kind in te skryf. Beeld, 23 January. [ Links ]

Christie P, Butler D & Potterson M 2007. Schools that work: a report to the minister of education. [ Links ]

Coetzee AS 2005. Drug testing in public schools. Africa Education Review, 2:275-298. [ Links ]

Darden CE 2006. School Law: safe from harm. American School Board Journal, 53-54. [ Links ]

Daily News 2009. Bullying must be stopped, 23 February. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2008. Understanding school leadership and governance in the South African context. Advanced Certificate in Education. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

Dilion N 2007. Planning to ensure that our schools are safe. American School Board Journal, 193:26-27. [ Links ]

Fraser D 2007. Proactive Prevention: A multi-pronged approach is most effective when addressing school safety. American School and University. [ Links ]

Free State Department of Education 2006. Number of schools per category. Bloemfontein: Free State Department of Education. [ Links ]

Fritz GK (ed.) 2006. Creating a safe, caring and respectful environment at home and in school. Brown University: Wiley Company. [ Links ]

Hosken G 2005. Drug pushers target pupils. Pretoria News, 10 February. [ Links ]

Hosken G 2009. Suspected leader of schoolgirl gang arrested. Pretoria News, 22 January. [ Links ]

Hosken G & Bailey C 2009. Schools use private firms for security after spate of attacks. Pretoria News, 31 January. [ Links ]

Huysamen GK 1993. Metodologie vir die sosiale en gedragswetenskappe. Halfweghuis: Southern Boekuitgewers (Edms) Bpk. [ Links ]

Kassiem A 2008. Lack of values pervades schools. Cape Times, 21 May. [ Links ]

Kotlolo M & Ratsatsi P 2009. Four girls gang terrorise classmates. Sowetan, 23 January. [ Links ]

Kuppan I 2008. Fatal stabbing, robbery raises school safety issues. Daily News, 28 January. [ Links ]

Maithufi IP 1997. Children, young persons and the law. In: Robin JA (ed.). The law of children and young persons in South Africa. Durban: Butterworth. [ Links ]

Jansen JD 2007. The research question. In: Maree K (ed.). First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Netshitahame NE & Van Vollenhoven WJ 2002. School safety in rural schools: are schools as safe as we think they are? South African Journal of Education, 22:313-318. [ Links ]

Ngobese N 2009. A school tragedy. The Witness, 12 February. [ Links ]

Nickerson AB & Martens MP 2008. School Violence: Associations with Control, Security/Enforcement Educational/Therapeutic Approaches and Demographic Factors. School Psychology Review, 37:228-243. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen IJ (ed.) 2003. Aspects of education law. Third edition. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen IJ, Rossouw JP & De Wet A 2004. Introduction to education law. First edition. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen IJ (ed.) 2005. Safe schools. Centre for Education Law and Policy. Pretoria: CELP. [ Links ]

Prinsloo IJ 2005. How safe are South African schools? South African Journal of Education, 25:5-10. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996a. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996b. South African Schools Act, 84 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Santos JRA 1999. A tool for assessing the reliability of scales. Journal of Extension, 37:1-5. [ Links ]

Skade T 2009. Two injured as dad fires at school principal. Star, 3 March. [ Links ]

Squelch J 2001. Do school governing bodies have a duty to create safe schools? Perspectives in Education, 19:137-149. [ Links ]

Thro W 2006. Judicial enforcement of educational safety and security: The American experience. Perspectives in Education, 24:65-72. [ Links ]

Trump KS 2008. Leadership is the key to managing school safety. District Administration. Cleveland. [ Links ]

Waghid Y 2003. Democratic education: policy and praxis. Department of Policy Studies. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University Printers. [ Links ]

Xaba M 2006. An investigation into the basic safety and security status of schools' physical environments. South African Journal of Education, 26:565-580. [ Links ]

Author

Gilbert Matsitsa is Associate Professor and Head of Department at the University of the Free State. His research focuses on effective school management, school discipline and safety, and student motivation. He has 23 years teaching experience.