Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.31 no.1 Pretoria ene. 2011

ARTICLES

The influence of township schools on the resilience of their learners

Ruth Mampane*; Cecilia Bouwer**

ABSTRACT

Many learners living in townships require protection and resilience to overcome obstacles and adversities in their context of development. The literature on resilience indicates strongly that resilience is embedded systemically. In the absence of constructive and supportive conditions in the home environment, the school would logically appear to be the next resource in line to be tapped. We investigated the contribution of two South African township schools to the resilience of their middleadolescent learners. Case studies with focus groups of resilient and less-resilient Grade 9 learners were used, following the Interactive Qualitative Analysis method, to determine the participants' perceptions of how the school contributes to the degree and nature of their resilience. The influence of the school varied depending on the degree of the learners' resilience, but also depending on factors within the school itself, suggesting that schools play a distinctive and determining role. Contributions particularly highlighted included creation, or failure to create, a supportive teaching and learning environment with effective implementation of rules and educational policy to provide care and safety for its learners and develop them to reach their future goals. Resilient learners were more ready than less resilient learners to acknowledge and utilise these characteristics. All focus groups placed much emphasis on goal attainment, suggesting a strong relationship with resilience.

Keywords: less resilient; middle-adolescent; resilient; township; township school

Introduction

Township residential areas in South Africa originated as racially segregated, low-cost housing developments, for black labourers to remain closer to their places of employment within the cities and towns. Today, township life is mostly associated with poverty, crime and violence and it has even been equated to a 'war zone', when the safety of residents becomes compromised (Harber, 2001; Leoschut, 2006; Prinsloo, 2007, 2005). The National School Violence Study (NSVS) conducted in 2008 by the Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention, in 245 South African schools, indicates that violence in schools relates to violence at home and is used as a legitimate form of resolving conflict by most learners. The research confirmed the occurrence of violence, crime and adverse conditions in townships, the developmental environment of many learners in South African schools (Burton, 2008). Most learners live in fear of experiencing crime and many contend with the absence of adult supervision and/or an unsafe learning environment (Xaba, 2006; Lubbe & Mampane, 2008). The demographic and socioeconomic distribution of the townships perpetuates racial segregation and a scarcity of resources in their public schools (Bush & Heystek, 2003). Most are characterised by violence and crime, poverty and unemployment of parents, and poor resources and overcrowded classes (Bush & Heystek, 2003; Harber & Muthukrishna, 2000; Onwu & Stoffels, 2005; Tihanyi & Du Toit, 2005; Prinsloo, 2007; Hammett, 2008). Theparents' limited contribution through school fees because of their low socioeconomic status places most township schools at a disadvantage (Hoadley, 2007; Lam, Ardington & Leibbrandt, 2010).

Learners living in townships require a good deal of protection and resilience to overcome the obstacles and adversities in their context of development. Success stories usually acknowledge the involvement of at least one significant person and/or other assets from the immediate environment. The social systems (family, school and community) play a major role in enhancing the inherent resilience potential of individuals (Thomsen, 2002). The literature on resilience indeed abounds with indications that resilience is embedded systemically (Werner & Smith, 1982 ; 1992; Thomsen, 2002; Masten & Reed, 2005). In the absence of constructive and supportive conditions in the home environment, the school is logically the next resource in line. Evidence exists that a supportive and safe school environment tends to buffer the effect of risk by providing protective factors and promoting resilience for its learners (Henderson & Milstein; 2004; Nettles, Mucherah & Jones, 2000; Theron & Theron 2010; Werner & Smith, 1982). Could the township school support or develop the resilience of its learners, given its intrinsic challenges and its problematic environment? Or would deficit thinking actually be a realistic perspective in that context?

We explored the question, 'How does a black-only township school influence the resilience of its middle-adolescent learners?' The purpose of the research was to understand the role of the township school, as a developmental and social system, in influencing resilience in learners growing up in a township. The learners' perceptions of what in their school environment influences their resilience would be expected to point to the strengths and weaknesses of the township school and thus suggest an appropriate course of supportive action.

Definitions of resilience generally look at successful or positive adaptation despite risk and adversity (Haggerty, Sherrod, Garmezy & Rutter 1996; Masten & Obradoviæ, 2006; Masten & Powell, 2003; Theron & Theron, 2010). Masten (1994) has alreadyviewed resilience as a process and declared that an understanding of resilience requires a description of the interactions of all the components essential to produce good adaptation, despite risk and adversity. Waxman, Gray and Padròn (2004) point out that the concept recognises that pain, struggle and suffering are involved in the process of being resilient. The following working definition was distilled from the resilience literature by a SANPAD research team (Mampane & Bouwer, 2006:444) and is preferred as it highlights the importance of identifying and accessing protective factors:

Resilience is having a disposition to identifyand utilise personal capacities, competencies (strengths) and assets in a specific context when faced with perceived adverse situations. The interaction between the individual and the context leads to behaviour that elicits sustained constructive outcomes that include continuous learning (growing and renewing) and flexibly negotiating the situation.

Risk factors impact negatively on the competence and resilience of individuals. Exposure to chronic stress and adversity and a lack of resources to mitigate the risks could lead to maladjustment (Compas, Hinden & Gerhardt, 1995) and thus less-resilience. Protective factors play a vital role to ameliorate risk and protect the individual from impending risks in the environment. Masten, Hubbard, Gest, Tellegen, Garmezy and Ramirez (1999) indicate that an individual's state of competence relates to the presence and quality of psychosocial resources as a strong protective factor, emphasizing that in most cases good resources are less common among children growing up in the context of adversity.

Three forms or stages of resilience have been distinguished, based on levels of adversity, adaptation and competence of the individual. These stages are resilience (good adaptation and high adversity history), competence (good adaptation and low adversity history) and maladaptation (poor adaptation and high adversity history) (Masten et al., 1999; Masten & Obradoviæ, 2006). Others argue that every individual has the potential to be resilient (Henderson & Milstein, 2003; Thomsen, 2002). We concur and, therefore, prefer using the terms resilience and less-resilience.

The article will outline Interactive Qualitative Analysis, the particular method of research that we adopted for the study, in some detail since the method is relatively new. The findings and discussion will be presented per focus group since the data of each group were analysed as a case. A synthesising discussion will subsequently address the research question, followed by some concluding thoughts on the need for further research.

Method

A multiple case study was undertaken in two township secondary schools, using Interactive Qualitative Analysis (IQA). IQA, developed by Northcutt & McCoy (2004), is a systems approach to research and functions within a constructivist and interpretivist frame. The rationale of the method is to actively engage focus group participants in constructing their unique understanding of the phenomenon under study by generating themes (called affinities) and in defining the relationships of influence that they themselves perceive to exist between the affinities. IQA focus groups are highly structured and follow specific sequential steps and processes to ensure trustworthiness. The metaphor used, to represent how a system is drawn from an IQA process, is that 'the purpose of IQA is to allow the group to create its own interpretive quilt, and then to similarly construct individual quilts of meaning', with the relationships proposed between the affinities then representing the 'stitches' of the 'quilt' (Northcutt &McCoy, 2004:43). The process will be explained more fully in describing the data collection.

Data collection

Contexts and participants

The IQA focus groups were conducted in two black-only secondary schools in the Mamelodi township, in Gauteng province, South Africa. Permission to conduct research in public schools was obtained from the Gauteng Department of Education and the Tshwane South District Office, and ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethics Unit of the University of Pretoria. Parents signed a letter of consent prior to the start of the research. The research process was described to all the participants and the letter of agreement was read to them. Only those who signed the letter were admitted into the study.

The two schools are within 5 km distance of each other and their feeder areas are both the formal and informal residential areas. Physically, they appeared fairly similar. Both displayed huge boards with their vision and mission and the description and explanation of the South African coat of arms, national fauna and flora and flag by the office block. In both schools, the main gates were manned by security guards and uniformed staff cleaned the school yards and office blocks. In both schools, also, classrooms were poorly lit (lights broken), with old, scratched chalk-boards, broken door handles and occasionally broken windows.

However, the administrative structure, discipline, infrastructure and ambience of the two schools differed. School 1 was situated between a primary school and an open field, presenting spaciousness on one side and continuity of school structures on the other. During school hours, parents and learners were frequently seen visiting the office of the Head of Department Life Orientation, for assistance and counselling and teachers customarily referred and sent learners and parents to her office for consultation and queries. After school, groups of learners cleaned the classrooms while others participated in extramural activities, which were often boisterous and occasionally disruptive. School 1 appeared disciplined and learner-oriented, striving to accommodate and support the emotional needs of parents and learners. In contrast, the poorly maintained facilities suggested a somewhat unsafe and depressing teaching and learning environment.

School 2 had shaded parking for staff and visitors. The school was on a busy road and between residential houses. The building was dilapidated. On occasion, when learners and parents visited the office block, appointments and referral problems would be discussed openly by teachers (one case involving a parent, learner and teacher was discussed outside, between the office block and classrooms). School 2 presented itself as a somewhat aloof environment, rather focused on discipline. After-school activities were minimal and few learners remained behind. Most disruptions in the afternoons came from teachers who were enforcing punitive measures and they would even interrupt focus group proceedings.

Two focus groups were conducted per school, one group consisting of resilient and one of less-resilient learners, each with two boys and two girls from Grade 9. The 16 participants were selected from 291 surveyed respondents on the basis of their resilience scores obtained on a self-developed resilience scale, the Resilience Questionnaire for Middle-adolescents in a Township School (R-MATS) (Mampane, 2010). Itemanalysis of theresilience characteristics in the R-MATS indicated a strong item-scale correlation of >.30 on all items, with the Cronbach alpha of 0.818 also indicating a good measure of reliability.

All resilient participants in School 1 had obtained the optimal score for resilience, whereas all the resilient participants in School 2 had a slightly less than optimal score. The resilience mean of the less-resilient participants of the two schools was fairly similar. The participants were not aware of their resilience status and the term resilience was never used during the focus group activities.

In Section A of the R-MATS, containing 11 items which address environmental risk factors (Mampane, 2010), all participants indicated the presence of at least one risk factor in their lives, e.g. the death of a parent, being abused, unemployment of a parent, or failing a grade in high school. The R-MATS results suggested overall that resilience correlated negatively with the measure of risk experienced.

Focus groups

Each focus group met after school on five days, for sessions of approximately two hours. In the first session, an issue statement was used to deconstruct and operationalise the research question. It required participants to engage and interrogate the following:

• How does the school contribute / fail to contribute to who you are?

• What is it that the school does / fails to do that makes you who you are?

In line with the IQA processdesigned by Northcutt and McCoy (2004), affinities (themes) were generated by each focus group, starting with the silent nominal phase, a brainstorming session which encourages the participants to produce thoughts and feelings individually. Each participant was provided with several clean index cards and colouring pens individually, to write each uncensored feeling and/or thought on a separate card, either as a word or a sentence. This activity was followed by affinity clarification and grouping (also done individually and in silence), during which participants arranged the pooled cards with similar meanings into sets, a process called inductive coding. The focus group then had to generate names or titles for the affinity sets, a deductive process requiring participants to be more specific and to deduce an affinity name from the meaning of the multiple cards in each set. During the next phase, the writing of paragraphs, each theme was discussed, the participants referring to their index cards to clarify what the words and sentences they had written meant in relation to the themes while the researcher composed a paragraph on the discussion. After each focus group discussion, the researcher typed the discussions and presented printed copies the following day for further discussion and consensus. The writing of paragraphs continued until the participants were satisfied with the definitions generated and were able to use the meanings for the final activity, theoretical coding, during which the participants individually and silently defined the relationship between the focus group affinities in terms of cause and effect.

System Influence Diagrams

A System Influence Diagram (SID) was constructed based on the relationships generated among the affinities by each focus group, further defining the position of each affinity as a driver, outcome, or pivot. A Primary Driver (PD) is characterised by influencing all other affinities directly or indirectly and mostly not being influenced by any itself. The Secondary Driver (SD) influences most affinities directly or indirectly while also being influenced by a few. The Primary Outcome (PO) is influenced directly or indirectly by all affinities and it influences none. The Secondary Outcome (SO) is influenced directly or indirectly by most affinities while it also influences a few. The Pivot occupies the middle position in the system, with an equal number of influences by and on other affinities, thus connoting the context or conditions within which the drivers operate to effect the outcomes.

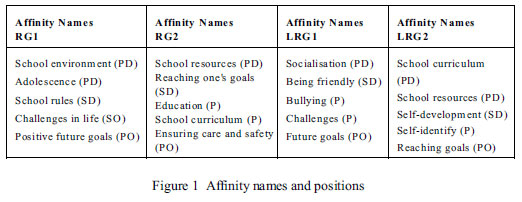

The affinities generated by the focus groups and the positions they occupy in the SIDs are contained in Figure 1. Focus groups were named according to their resilience status and school, e.g. RG1 (Resilient Group, School 1) and LRG1 (Less Resilient Group, School 1).

Findings emerging from focus group SIDs

Resilient Group, School 1

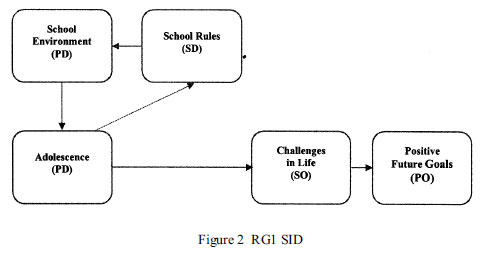

RG1 perceived the affinities School Environment and Adolescence as PDs and School Rules as an SD. Based on the descriptions of the affinities they constructed initially, RG1 was stating that their school environment, as particularly created, determines that their particular needs as adolescents are met, which in turn shapes the school rules as particularly designed and applied within their school. The three affinities resulted in a feedback loop of drivers, with school rules again shaping the school environment. The adolescent stage further determines which Challenges in Life they are presently facing as an SO, which in turn influences them to strive for Positive Future Goals, the PO. Figure 2 is a representation of the SID.

The SID in Figure 2 comes perhaps as a pleasant surprise in showing that the resilient learners in School 1 clearly acknowledged the importance of consistent practice and the security of knowing what is right and wrong, including principles of moral development, in a school environment, for them to achieve adequate support for the unique needs and challenges of adolescence. Theyrecognised that the school environment is positively influenced by school rules, which constitute principles of governance and policy, as well as the ethos, vision and mission of the school. A school that caters for the needs of its learners should function within the functionalist model, where order takes precedence, with clearly defined roles and expectations. This is well explained by Jansen's (2004:384) declaration that,

everycomponent of the school, working with the others, enables the institution to function smoothly and predictably in achieving the mission and objectives of the school.

It is also noteworthy that RG1 viewed the challenges they were experiencing as an outcome of the life phase they were in, suggesting an internal locus of control instead of a tendency to blame circumstances.

Less-resilient Group, School 1

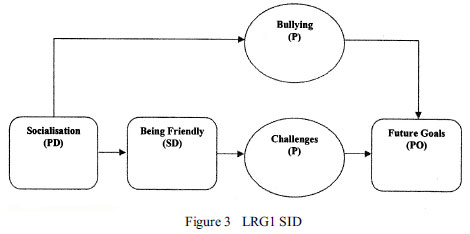

In marked contrast, Figure 3 shows that LRG1 perceived the affinity Socialisation as the sole PD and not in any way attributable to the school. The group defined socialisation as 'how one was raised, one's values and culture', with family as the primary socialisation agent. Even though the school is generally recognised as a socialisation agent (Louw & Louw, 2007; Parsons, Bales, Olds, Zelditch & Slater, 1956), LRG1 emphasised the parents' role exclusively. The learners argued that moral development, including differentiation between right and wrong and respect for others, is learned before starting formal education.

LRG1 acknowledged that not all children are socialised the same by stating that socialisation influences who one is, a bully or a friendly person. Thus, some observed behaviour at school portrays some learners as friendly and others as bullies. Being Friendly is positioned as an SD while both Bullying and Challenges have pivotal status. In this view, a bullying disposition actually forms a context in itself, the negative frame of perspective and behaviour which results in future goals not being reached or in themselves even being undesirable. LRG1 defined a bully as 'a bad person, a naughty and delinquent person'. By contrast, being friendly, as a driver, influences or even determines how the individual engages with people and issues within the context of challenging circumstances and the individual then emerges from challenges to attain the goals set for the future. The challenges, according to this group, are thus accepted as part of growing up. Future Goals are constituted as PO and defined as what the participants want to be when they grow up, doing the job one wants.

For LRG1, the school therefore only featured in being part of the context containing the challenges. Challenges were positively constructed in discussion of the affinities (they include active participation in finding solutions to problems) and in this way have a positive influence on how the desired future goals are attained. The group indicated that dealing with challenges constructively, i.e. with friendliness, helps in growth and development. Since bullies do not engage positively with challenges, but instead force, threaten and manipulate their way directly through to their goals, they lose out on the experiences of friendly learners when exposed to challenges. The attainment of future goals by the two personality types will thus be different in the degree of attainment as well as the range.

Resilient Group, School 2

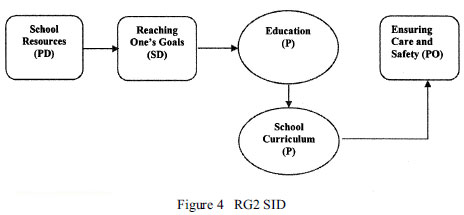

RG2 rather unexpectedly perceived the affinity School Resources as a PD and Reaching One's Goals even more unusually as an SD. The strong causal connection between the two show that RG2 perceived access to school resources to directly influence their ability to plan successfully and to reach their goals. RG2 explicitly, according to their description of the affinities, perceived lack of access to school resources as detrimental to their goals. They positioned both Education and School Curriculum as pivots, the playing field or context within which the availability and quality of the school resources and goal attainment take effect. Therefore it can be assumed that access to school resources and experiences of success will enable the learners to benefit effectively from teaching and learning in the 'right' subjects that will enable them to gain more knowledge, and that again influences the PO of the school's role of providing care and safety for its learners. However, lack of access to school resources and the sense of frustration and failure in missing their goals also influence the quality of education and the curriculum of the school, thus negatively affecting the outcome of care and safety for its learners. Figure 4 is a representation of the SID.

In conclusion, RG2 viewed the ultimate role of the school as ensuring care and safety for its learners, i.e. enforcing discipline, school rules, and maintaining order. RG2 stated that

I am who I am primarily because of the resources my school provides me with (or doesn't provide), which lead to the particular goals that I reach (or do not reach) in requiring me to learn the subjects provided by the curriculum in my education. My school consequently contributes to the degree of care and safety I experience (or don't experience) in the rules and social principles I am taught.

RG2 stated simply that 'the school can ensure that we are provided with care and safety' or, based on the negative statements in their definition of affinities, 'the school does not ensure that we are provided with care and safety'. In a similar study conducted by Enthoven in the Netherlands (2007), the resilient adolescents provided examples of their experiences of safety and good education provided by the school, whereas the 'not resilient' [sic] adolescents from the same school environment provided negative examples, i.e. of their experiences of 'less' safety and 'good' education.

Less-resilient Group, School 2

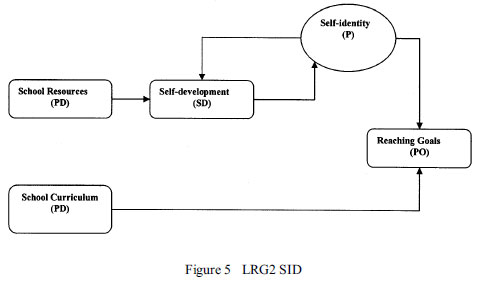

LRG2 perceived both School Resources and School Curriculum as PDs, but with distinctly different effects. School resources influence Self-development, an SD, which in turn influences Self-identity as a pivot, leading into the PO, Reaching Goals. The school curriculum in the view of LRG2 directly influences their reaching of goals. Figure 5 is a representation of the SID.

LRG2 places personal considerations quite centrally, in noting a circular relationship between self-development and self-identity as a feedback loop of influence and effect on each other. The two affinities, however, have different effect-statuses. Self-development as the SD, if healthy, could lead to a pivotal positive self-identity, a healthy sense of self as a frame of reference, a springboard from which to reach one's goals. Again, poor availability of resources, much emphasised in LRG2's description of the affinities, impacts negatively on selfdevelopment, causing a flawed, unhealthy sense of self to deny an individual the prospect of reaching planned goals. Unhealthydevelopment, the lack of growth, improvement and progress indeed leads to role confusion, and poor future prospects, as it is clearly indicated in Erikson's developmental stage of adolescence as identity vs. identity confusion (Erikson, 1980; Louw & Louw, 2007).

The SID further indicates that another PD, the school curriculum, influences the PO of reaching goals directly. This relationship highlights the importance in the view of LRG2 of offering the 'right' subjects as it directly influences the reaching of goals. LRG2 defined both PDs negatively and relatively similarly, i.e. school resources as lack of access to available school resources, e.g. the library and computer laboratory, and school curriculum as subjects the school does not offer but that were viewed essential for their future and thus affecting them as obstacles in reaching their goals.

Discussion

We obviously cannot generalise from qualitative research results drawing on only two schools, with only two resilient and two less-resilient focus groups, inter alia because differences between the results of two contexts can only be noted, but not explained. But some points of comparison certainly merit contemplation and further research.

The difference between the two schools seems to be over-arching, but a consistent pattern of difference is also apparent between the resilient and less-resilient participants. The SIDs generated by School 1 participants positioned the affinities Challenges in Life (SO) and Challenges (P) to directly influence the PO, Positive Future Goals and Future Goals. The middle-adolescents from School 1 affirmed the influence of challenges on their future goals and the importance of resolving challenges positively to ensure attainment of positive future goals. School 1 SIDs confirm the importance of providing life skills to assist middle-adolescent participants in dealing with the challenges they perceived in their school environment and within themselves.

What differed most markedly in the SIDs of resilient and less-resilient participants of School 1 was the relevance accorded to the influence of the school. RG1 acknowledged School Environment and School rules as PD and SD, respectively, thereby elevating qualities of the school to the ultimate causal sphere, whereas LRG1 relegated the contribution of the school to merely forming a context within which challenging experiences are dealt with, expressly stating that their development of socialisation skills within their homes is decisive in who they become. RG1 and LRG1 participants thus differed regarding their understanding of the constructive role of the school as context of their development. RG1 were achievement-oriented and acknowledged the important role of the school in ensuring achievement of their goals. LRG1 focused more on themselves and acknowledged the school far less, as to them merely a context of experiences where different personalities (being friendly and bullying) meet and encounter life's challenges.

The SIDs presented by School 2 middle-adolescents contain three similar affinities, School Resources, Reaching Goals / Reaching One's Goals and School Curriculum, but with different positions of influence. The emphasis on resources and curriculum suggest a utilitarian view which might actually have been formed by their perception of inadequacies in the school and may in fact have contributed to the slightly lower scores of the resilient learners in comparison with School 1. School 2 middle-adolescents perceived that by making resources available and presenting a good school curriculum the school would be able to provide them with the requirements for goal attainment, but that this was not being done.

RG2 viewed the availability or not of school resources as a direct influence on reaching one's goals or not, and LRG2 thought that the (un)availability of school resources actually had a (negative) influence on their very development, and indirectly also their sense of identity. RG2 perceived that the school curriculum, which is positioned as a P, forms the frame within which they are provided (or not) with care and safety (also a somewhat utilitarian outcome), while LRG2 positioned the (unsatisfactory) school curriculum as a primary driver which influenced their (limited) prospects of reaching goals.

RG2 and LRG2 participants are seen to voice a clear discourse on lack of resources within the school as their foremost concern. All the participants were focused on the school's failure to provide for them and were less acknowledging of any other role the school may have played. By contrast, RG1 could be regarded as a model of resilience in a 'good' school. Not only did they display optimally those attributes typically found in the research literature on resilience (Werner & Smith, 1982; Thomsen, 2002; Henderson & Milstein, 2003), but they were aware of, and utilised, what the school offered for their healthy development. The affinities generated by the less-resilient focus groups of both schools reflect a focus on self that suggests they were experiencing some uneasiness or discomfort about 'who they are' and recognised their need for stronger development. However, as was also found by Enthoven (2007), they neglected to access the services and resources that were available to them.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by RG1, township secondaryschools are possibly able to create a constructive environment for resilient learners who are experiencing adversity, by exercising clear rules of conduct, yet accommodating the learners' needs as adolescents. The results of RG2, however, suggest that not all township secondary schools succeed in effectively supporting their resilient learners. The role of the township secondary school in support of less-resilient learners appears a matter for utmost concern. Several challenges confront the township secondary school management if they are to avoid failing a vital group of learners contending with adverse circumstances. The fact that goal attainment featured as an affinity in all the focus groups underscores the far-reaching influence of the township secondary school on the long-term development of its learners. No teacher or manager may say they are there for the transmission of knowledge and skills alone. Our study has thrown up proof of adolescent learners' perceived dependence on the township school for what they will make of their future lives. A need for research and focused school management on numerous issues such as the following is certainly indicated: How could the disciplinary policy of a township secondary school be made to contribute to the wellbeing and development of all its learners? How could the township secondary school bring its supportive goals and resources, e.g. a programme or the availability of its staff, to the attention of specifically the less-resilient learners? Should the township secondary school engage practically with the hardships their learners are experiencing? How could less-resilient learners in township secondary schools be identified, and how could their resilience be supported and/or developed? Ultimately, this ball has now landed firmly in the court of the school management team.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the financial support for the entire project from SANPAD.

References

Burton P 2008. Merchants, Skollies and Stones: Experiences of School Violence in South Africa. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. [ Links ]

Bush T & Heystek J 2003. School governance in the new South Africa. Compare, 3:127-138. [ Links ]

Compas BE, Hinden BR & Gerhardt CA 1995. Adolescent development: Pathways and process of risk and resilience. Annual Review of Psychology, 46:265-293. [ Links ]

Enthoven M 2007. The ability to Bounce Beyond: The contribution of the school environment to the resilience of Dutch urban middle-adolescents from a low socio-economic background. Amsterdam: Boekservice Amsterdam. [ Links ]

Erikson EH 1980. Identity and the life cycle. USA: W.W. Norton & Company. [ Links ]

Haggerty RJ, Sherrod LR, Garmezy N & Rutter M 1996. Stress, risk, and resilience in children and adolescents: Process, mechanisms, and interventions. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hammett D 2008. Disrespecting teacher: The decline in social standing of teachers in Cape Town, South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 28:340-347 [ Links ]

Harber C 2001. Schooling and violence in South Africa: creating a safer school. Intercultural Education, 12:261-271. [ Links ]

Harber C & Muthukrishna N 2000. School effectiveness and school improvement in context: The case of South Africa. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 11:421-434. [ Links ]

Henderson N & Milstein MM 2003. Resiliency in schools: Making it happen for students and educators, Updated edn. California: Corwin Press Inc [ Links ]

Hoadley U 2007. The reproduction of social class inequalities through mathematics pedagogies in South African primary school. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 39:679-706. [ Links ]

Jansen J 2004. Changes and continuities in South Africa's higher education system, 1994 to 2004. In: Chisholm L (ed.). Changing class. Education and social change in post-apartheid South Africa. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Lam D, Ardington C & Leibbrandt M 2010. Schooling as a lottery: Racial differences in school advancement in urban South Africa. Journal of Development Economics, 1-16. [ Links ]

Leoschut L 2006. The influence of family and community violence exposure on the victimisation rates of South African youth. Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention, Issue Paper No. 3:1-11. [ Links ]

Louw D & Louw A 2007. Child and adolescent development. Free State: ABC Printers. [ Links ]

Lubbe C & Mampane R 2008. Voicing children's perceptions of safety and unsafety in their Life-worlds. In: Ebersöhn L (ed.). From Microscope to Kaleidoscope: Reconsidering Educational Aspects Related to Children in the HIV&AIDS Pandemic. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Mampane MR 2010. The relationship between resilience and school: A case study of middle-adolescents in township schools. PhD thesis. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Mampane MR & Bouwer AC 2006. Identifying resilient and non-resilient Grade 8 and 9 learners in a township school. South African Journal of Education, 26:443-456. [ Links ]

Masten AS 1994. Educational Resilience in Inner-City America: Challenges and Prospects. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associate Publishers. [ Links ]

Masten AS, Hubbard JJ, Gest SD, Tellegen A, Garmezy N & Ramirez M 1999. Competence in the context of adversity: Pathways to resilience and maladaptation from childhood to late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 11:143-169. [ Links ]

Masten AS & Obradoviæ J 2006. Competence and Resilience in development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094:13-27. [ Links ]

Masten AS & Powell JL 2003. A resilience framework for research, policy and practice. In: Luthar SS (ed.). Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Masten AS & Reed MGJ 2005. Resilience in development. In: Snyder CR & Lopez SJ (eds). Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Nettles SM, Mucherah W & Jones D 2000. Understanding resilience: The role of social resources. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 5:47-60. [ Links ]

Northcutt N & McCoy D 2004. Interactive Qualitative Analysis: A systems method for qualitative research. California: Thousand Oaks. [ Links ]

Onwu G & Stoffels N 2005. Instructional functions in large, under-resourced science classes: Perspectives of South African teachers. Perspectives in Education, 23:79-91. [ Links ]

Parsons T, Bales RF, Olds J, Zelditch M & Slater PE 1956. Family socialization and interaction process. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Prinsloo E 2007. Implementation of life orientation programmes in the new curriculum in South African schools: Perceptions of principals and life orientation teachers. South African Journal of Education, 27:155-170. [ Links ]

Prinsloo E 2005. Socio-economic barriers to learning in contemporary society. In: Landsberg E, Kruger D & Nel N (eds). Addressing barriers to learning: A South African perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Theron LC & Theron AMC 2010. A critical review of studies of South African youth resilience, 1990-2008. South African Journal of Science, 106:252. [ Links ]

Tihanyi KZ & Du Toit SF 2005. Reconciliation through integration? An examination of South Africa's reconciliation process in racially integrating high schools. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 23:25-41. [ Links ]

Thomsen K 2002. Building resilient students: Integrating resiliency into what you already know and do. California: Corwin Press Inc. [ Links ]

Waxman HC, Gray JP & Padrön YN 2004. Promoting educational resilience for students at-risk of failure. In: Waxman HC, Padrön YN & Gray JP (eds). Educational Resiliency: Students, teacher, and school perspectives. United States of America: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Werner EE & Smith RS 1982. Vulnerable but invincible: A longitudinal study of resilient children and youth. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Werner EE & Smith RS 1992. Overcoming the odds: High risk children from birth to adulthood. London: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Xaba M 2006. An investigation into the basic safety and security status of schools' physical environment. South African Journal of Education, 26:565-580. [ Links ]

Authors

Ruth Mampane is Lecturer in the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Pretoria. Her research interests are in resilience, HIV/AIDS, adolescence, and IKS.

Cecilia Bouwer is Professor Emeritus, formerly of the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Pretoria. Her special interest is in development of new assessment procedures and instruments, within a model of assessment for learning support.