Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.31 no.1 Pretoria Jan. 2011

ARTICLES

Improving school governance through participative democracy and the law

Marius H Smit*; Izak J Oosthuizen**

ABSTRACT

There is an inextricable link between democracy, education and the law. After 15 yearsofconstitutional democracy, the alarming percentage of dysfunctional schools raises questions about the efficacy of the system of local school governance. We report on the findings of quantitative and qualitative research on the democratisation of schools and the education system in North-West Province. Several undemocratic features are attributable to systemic weaknesses of traditional models of democracy as well as the misapplication of democratic and legal principles. The findings of the qualitative study confirmed that parents often misconceive participatory democracy for political democracy and misunderstand the role of the school governing body to be a political forum. Despite the shortcomings, the majority of the respondents agreed that parental participation improves school effectiveness and that the decentralised model of local school governance should continue. Recommendations to effect the inculcation of substantive democratic knowledge, values and attitudes into school governance are based on theory of deliberative democracy and principles of responsiveness, accountability and justification of decisions through rational discourse.

Keywords: accountability; deliberativedemocracy; participation; school governance

Introduction

Every democratic society faces the challenge of educating succeeding generations of young people for responsible citizenship. The present state of democratisation in South Africa has been likened to a teenager going through a rebellious growth stage of puberty as a result of historic shackles, inappropriate structures, erroneous conceptions of democracy and the sheer misapplication of the law (Wiechers, 2008). Chaskalson (2009) has acknowledged that the constitutional jurisprudence (i.e. case law and legal theory) has not developed a coherent system of democracy and that theories of democracy are not well developed. This is particularly evident in the education system where the whole-school evaluation programme has revealed that approximately 80% of the schools in South Africa are essentially dysfunctional (Taylor, 2006:2).

Our contention in this paper is that the crisis presently experienced in the education system is partly attributable to misconceptions of democracy, misapplications of legal and democratic principles, and systemic weaknesses in traditional models of democracy.

Objective

Based on the above problem statement, the purpose of this paper is to analyse and explain some phenomena relating to the process of democratisation from a multidisciplinary (viz. legal, educational and political theory) perspective, with particular reference to undemocratic trends apparent in school governance in the education system.

Methodology

We applied three research methods to achieve the aims of this research. Firstly, a comprehensive literature review of political theory was conducted to conceptualise key tenets of democracy and to identify undemocratic trends by means of a historic-legal and comparative legal analysis of South African as well as foreign sources of law.

Secondly, advancing from a positivist paradigm, a quantitative study was undertaken to analyse variables, factors and indicators of democratic attitudes and opinions of public school governance. The survey was conducted in four phases. The target populations included the principals and school governing body chairpersons of primary, secondary, combined, special education and farmschools providing public education as well as senior education officials that were responsible for administration of school governance and school management in the 19 school districts1 of the North-West Province. All independent schools were excluded from thepopulation. This demarcation was necessary in order to focus on the aim of the study to research democracy at the meso level of public school education.

Initially 401 questionnaires were distributed by post to randomly selected school principals and school governing body chairpersons in public schools in North-West Province. By virtue of the random method the respondents were representative of the demographic diversity of the province, ranging from rural and farm schools to township and suburban (ex-model C) schools. However, as a result of the relatively poor rate of return (see Table 1), it was decided to switch to convenience sampling methods which comprised the collection of data during two workshops. The first workshop was arranged by the District Office of the Southern Region of the North-West Education Department and was attended predominantly by principals and school governing body chairpersons from township and rural schools.

The second workshop was arranged by the Federation of South African School Governing Bodies (FEDSAS) and was attended predominantly by principals and school governing body chairpersons of suburban (ex Model-C) schools in North-West Province. The final phase of data collection entailed the distribution of questionnaires by hand to all the senior education officials in the Education-Management-Governance-Development departments ("EMGD-Department") of all the Area Project Offices in North-West Province. The samples of school principals and school governing body chairpersons represented a broad socio-economic spectrum of public schools ranging from previously advantaged and disadvantaged urban, suburban and township schools to impoverished rural schools. It was expected that the respondents would be representative of diverse segments and perspectives on the issue of democracy in education. Ultimately, the four phases of sampling resulted in the distribution of 1,282 questionnaires and rendered a total of 456 responses as set out in Table 1.

The adequacy of the response rate was confirmed and the results were analysed with the assistance of the Statistical Consultation Services of the North-West University (Ellis, 2008).

Thirdly, advancing from an interpretivistic paradigma phenomenological qualitative study was undertaken after the quantitative study by conducting eight non-random interviews of purposely selected EMGD-officials of the North-West Department of Education until a level of saturation was achieved (Leedy & Ormrod, 2005:145). This qualitative study was undertaken in order to verify, confirm or refute findings of the quantitative study; determine and describe the participants' conceptualisation and understanding of democracy, establish the participants' views of democracy in education, explore and interpret certain bureaucratic phenomena, practices and trends in the education system of the North-West Province, and to ascertain or explain the underlying reasons and motives for these phenomena. In keeping with the interpretivistic approach, the transcripts of the interviews were analysed by means of open coding, axial coding and selective coding of the data (Merriam, 2008). The open-ended questions posed during the semi-structured interviews aimed to examine the participants' perspectives on phenomena such as conceptualisation of democracy, knowledge of Education Law and democratic principles, bureaucratic practices and reasons for poor parental participation. Cohen et al. (2001:103) explain that in purposive sampling, researchers handpick the cases or participants to be included on the basis of their judgment of their typicality. We purposely selected expert participants from the EMGD-officials most likely to have administration experience, actual knowledge of school governance and the phenomenon of democracy in the education system in the province.

Finally, the findings of the three methods were triangulated, evaluated and synthesised in order to develop a coherent theory of improving school governance by means of deliberative democracy and the law.

Democracy, education and the law

There is an inextricable link between democracy, education and the law. This interrelationship is evident from the Constitution, International Law and education legislation. The following examples catalog this interrelationship:

• The founding provision of the Constitution (§1) confirms that South Africa is a democracy based on the rule of law;

• Several of the fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution, including the rights to education (§29); equality (§9), human dignity (§11); freedom of expression (§16); freedom of association (§18); freedom of religion, belief and opinion (§15); the right to use language and culture of choice (§30); and the right to belong to a cultural, religious and linguistic community have particular significance for education;

• The Convention on Prevention of Discrimination in Education endeavours to respect the diversity of education systems and provides that the establishment or maintenance, for religious or linguistic reasons, of separate education systems which is in keeping with the parent's or legal guardian's education, does not constitute discrimination (§1).

• Article 30 of the Convention provides that in those states in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities or persons of indigenous origin exist, a child belonging to such a minority or who is indigenous shall not be denied the right, in community with other members of his or her group, to enjoy his or her own culture, to profess and practise his or her own religion, or to use his or her own language;

• African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (SA, 2000) affirms the democratic values and provides in section 2 that the education of the child must be directed to the preservation and strengthening of positive African morals, traditional values and cultures; the preparation of the child for responsible life in a free society, in the spirit of understanding tolerance, dialogue, mutual respect and friendship among all peoples ethnic, tribal and religious groups;

• The preamble of the National Education Policy Act (SA, 1996a) provides that legislation should be adopted to facilitate the democratic transformation of the national system of education into one that serves the needs and interests of all the people of South Africa and upholds their fundamental rights;

• The directive principle in section 4(m) of the National Education Policy Act (SA, 1996a) contains the democratic requirement that the national Minister of Education must ensure broad public participation in the development of education by including stakeholders in policymaking and governance in the education system (SA, 1996a);

• Section 4(b) of National Education Policy Act expressly contains the principle that policies should be developed to include the advancement of democracy in the education system;

• The South African Schools Act ('Schools Act') gave formal effect to a participative form of democracy by redistributing power to local school governing bodies with the removal centralised control over certain aspects of educational decision-making and the establishment of co-operativegovernance between education authorities and the school community (Squelch, 1998:101; Oosthuizen et al, 2003:195). In principle these provisions were intended to establish a democratic power sharing and co-operative partnership among the state, parents, and educators (Karlsson, 1998:37);

• In terms of the Schools Act, members of school governing bodies are democratically elected to represent parents, educators, learners and personnel of a school. School governing bodies have the democratic and statutory authority to adopt a constitution (§20); recommend appointment of staff (§20), determine the language policy of a school (§6), take measures to ensure learner discipline at schools (§8, §9), and control of school property and financial resources (§20, §21).

Consequently, it is evident that a number of legal instruments contain provisions that require democratic transformation through education, fundamental rights and the law. However, these legal instruments are silent on the nature, tenets and principles of democracy and do not stipulate the application of any particular model of democracy. This will be discussed in the next section.

Conceptualising democracy

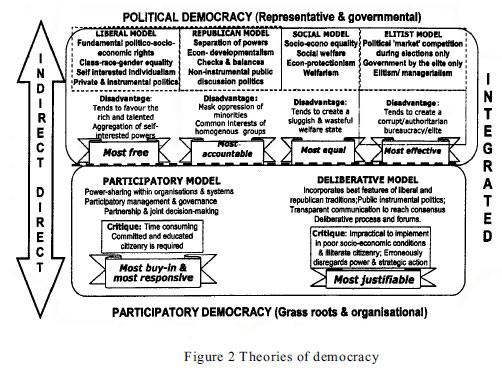

Theories of democracy have evolved over the centuries from the model direct democracy in ancient Athens to the modern representative models of liberal democracy, republicanism, Schumpetarian elitism, participative democracy and deliberative democracy. There are differences between the main democratic theories. As such, no definition can include all the variations to satisfy the proponents of each theory. Briefly, in order not to digress unnecessarily, the main democratic theories are given in Figure 1.

The salient features, values, points of critique and disadvantages of each theory are depicted in Figure 2. In the interest of parsimony, these theories will not be discussed in detail as much scholarly research has been devoted to this topic (Chapman & Dunstan, 1990; Blaug & Schwarzmantel, 2000; Cunningham, 2002; Dewey, 1916, Fishkin & Laslett, 2003; Habermas, 1996; Held, 1987; Kotze, 2004; Kymlicka, 2002; Pateman, 1970; Popper, 1971; Schumpeter, 1943; Steyn, Du Plessis & De Klerk, 1999; Tarrant, 1989; Wiklund, 2005).

Myburgh (2004:12) reminds us that there is an ongoing ideological battle over the meaning of democracy. The South African Constitution includes an unequivocal commitment to representative and participatory democracy; incorporating the concepts of accountability, transparency and public involvement (SA, 1996a). Theoretically defined, participatory democracy refers to a form of direct democracy that enables all members of a society to participate in decision-making processes within institutions, organisations, societal and government structures. Adams and Waghid (2005:25) regard participation, community engagement, rationality, consensus, equality and freedom as the constitutive principles of the South African democracy. With the increasing decentralization of fiscal, political, and administrative responsibilities to local spheres of government, local institutions, and communities, the notions of participation and deliberation have emerged as fundamental tenets in the promotion of the local governance of schools (Grant Lewis & Naidoo, 2004:1). The policy of decentralization of education according to participatory democratic theory has become a key aspect of educational restructuring in the international arena (Aspin, 1995:30; Sayed 1999:141; Karlsson, 2002:327-336).

Deliberative democracy is the most recent theory that suggests an improved form of democracy through the implementation of deliberative principles based on Habermasian discourse ethics (Eriksen & Weigard, 2003:128). Theoretically defined, deliberative democracy refers to the notion that legitimate political decision-making emanates from the public deliberation of citizens. In other words, as a normative account of political decision-making, deliberative democracy evokes ideals of rational legislation, participatory politics and civic self-governance (Cunningham 2002: 163). Adams and Waghid (2005:25) regard participation, community engagement, rationality, consensus, equality and freedom as the constitutive principles of deliberative democracy in South Africa.

Proponents of deliberative democracy suggest that, in principle, deliberative democracy has applied the most attractive features of liberal and republican theories, and has avoided the shortcomings of the traditional theories. The four principles of deliberative democracy, viz. generality, autonomy, power neutrality and ideal role-taking, are standards whereby the applicability of deliberative theory can be measured (Eriksen & Weigard, 2003:128). The deliberative model of democracy maintains that citizens are treated equally when the exercise of political or bureaucratic power can be justified by reasons, which can be approved by all after adequate rational deliberation has taken place (Eriksen & Weigard, 2003:128).

Nevertheless, substantive democracy, however defined, has not been fully realised anywhere in the world because all the traditional models of democracy (i.e. liberal, republican, social and elitist) have inherent weaknesses and flaws such as the favouring of the rich and talented, the oppression of minorities, aggregation of self-interested decision-making, dominance of hegemonies, wasteful welfarism and corrupt or authoritarian elitism and bureaucracy are all embedded in the system (Cunningham, 2002:1-248). Of course, this also implies that all the weaknesses of the liberal, republican, social and elitist traditions of democracy are present in the South African political and social system. This will be investigated in the sections that follow.

Undemocratic features in the South African education system

Several undemocratic features are present in the system of school governance and will be discussed in more detail in this section.

Systemic weaknesses

Systemic weaknesses of the traditional models of democracy(i.e. liberal, republican, social and elitist) are evident from the following examples in the education system:

• The former Model C schools (generally well-resourced and previously advantaged) are functioning and performing well with the present model of state-aided school governance, whereas most of the previously disadvantaged schools are dysfunctional (Taylor, 2006:3). Thus, liberal democratic features in our system inherently favour the previously advantaged schools;

• Language rights of African learners as well as Afrikaans single medium schools are disrespected or disparaged by provincial officials. The quantitative study of this research revealed that the issue of centralisation of language policy for schools elicited effect sizes of large practical significance (phi coefficients: 0.54; 0.5; 0.71) and statistical significance (χ2 values: 0.0054) between all the sub-groups of the senior education officials; school principals and school governing body chairpersons. The Afrikaans sub-groups (81.5%) held strong views against centralisation of school language policy, whereas the majority of the Setswana et al. group were in favour of centralisation of language policies by the provincial education department. Thus, typical features of republican democracy, such as the emphasis on separation of state powers, inherently enables or masks oppression of minorities;

• Alexander (2003:184) aptly criticised the wastage of the system as is evident from the annual poor matriculation results and the high drop-out rate. In 2005 the results were so poor that only 150,000 Grade 12 learners (representing 12.5% of the initial 1.2 million Grade 1 learners) achieved a matriculation pass that is of an acceptable standard (Gallie, 2007:5). Yet, despite these poor results, no vigorous disciplinary action was taken against incompetent or uncommitted educators. Thus, social democratic features inherent to the system causes wasteful welfarism;

• There is a strong trend towards centralised control of education policy for transformation purposes (see discussion following). This causes conflict between the government (including provincial departments of education) and school governing bodies in matters such as the appointment of educators (Settlers Agricultural High School v The Head of Department:Department of Education, Limpopo Province, 2002), determination of language policies (Head of Department, Mpumalanga Education Department v Hoërskool Ermelo, 2009) and learners' admission policies. Thus, these indicators substantiate the contention that the elitist features of the system inevitably favour an authoritarian bureaucracy.

Therefore, the inherent weaknesses of the liberal, republican, social and elitist traditions of democracy are present in the education system and cause phenomena such as great disparities between schools, oppression of minorities, wastage of financial resources, elitist and bureaucratic attitudes.

Misconceptions of democracy

Due to the absence of a long democratic tradition and the democratic immaturity of the majority of South Africa's citizenry, many of the problems in the system of school governance can be attributed to ignorance and lack of knowledge of democratic principles. This is evident from a telling admission of a senior education official who stated:

We should have gone back to the communities to demobilise the people to change their mindset. To change their mindset by saying, now we are in a democracy now [sic]. From a revolutionary to a democratic mindset. (Interview 2, Ln: 171-175).

... the democratic immaturity of the parents is taking its course. But our children at the communities were not demobilised. After 1994, we should have put structures in place. (Interview 2, Ln: 204-207).

To give an example from the quantitative study, 60% of the senior education officials and 50% of the other participants misunderstood democracy to mean that the majority should always triumph regardless of whether fundamental rights are infringed. This is clearly erroneous as Tocqueville (1966:8) axiomatically stated that unbridled majority rule may become an oppressive 'tyranny of the majority' and that the majority of the self-governing citizens is always limited by the law of justice, which is established by the majority of all mankind. The erroneous majoritarian 'winner-takes-all' notion explains why many of the bureaucratic decisions are taken to enforce the government and ruling party's aim to transform education without due regard to fundamental rights and requirements of legality. Of the senior education officials, 91.2% incorrectly assessed their own knowledge of democratic principles to be good or excellent.

A second example is the finding that 57% of the respondents were ignorant of the principles of participatory and deliberative democracy as mechanisms to manage diversity and accommodate multiculturalism. In fact, the majority of the respondents favoured a bureaucratic method to manage multiculturalism. This does not accord with the principle that education and democracy are interconnected and that a democratic culture can only be developed by democratic education practices (Parry & Moran, 1994:48). Most of the stakeholders in education do not understand the differences between political and participatory forms of democracy. For instance, meaningful participation by parents in school governance is constrained if bureaucratic misapplications of democratic principles occur as a result of the restrictive paradigms that curtail the rights of school governing bodies to recommend the appointment of educators (Carnavon High School v MEC for Education, Northern Cape; Douglas Hoërskool v The Premier of the Northern Cape Province; Kimberley Girls High School v. Head of the Department of Education, Settlers Agricultural High School v. Head of Department of Education, Limpopo Province).

Misapplication of legal and democratic principles

The findings indicate a pattern of misapplication of the rule of law and principles of democracy such as enabling participation and tolerance of diversity of languages.

The first indication of a pattern of misapplication of democratic principles is the failure to apply the rule of law. This is evident from the reluctance of the departments of education (provincial and national) to address the inordinately political role that the dominant teacher's (SADTU) union plays. The qualitative evidence confirmed that "the dominant teacher organisation seems to think that it is running the system and teachers are not doing what they are expected to do" (Interview 6, Ln:38-39) and that this union is responsible for the politicised climate in dysfunctional schools (Interview 2, Ln:120-127). A senior education official explained the conduct of SADTU as follows:

Now, for the past two, three months, those educators which are members of a union which is affiliated to COSATU, were not in the classrooms. You must look at the results this year; I think it is going to be adversely affected. That is why I am saying, in one way or the other, this union is having a political mandate from the ruling party or their union federation. So, therefore, whenever they come to school they want to politicise everybody, even political leaders. That is why you find that the school governing bodies today are operating under very, very, tremendous [sic] pressure from the unions (Interview 2: Ln:120-127).

Although the participants were reluctant to name the union eo nomine, it is general knowledge that the dominant teachers' union, in terms of membership numbers and affiliation to the Confederation of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), is the South African Democratic Teacher's Union (SADTU).

Furthermore, 23.93% of the respondents indicated that unions often or always unlawfully interfere with the recommendations of school governing bodies to appoint educators. It was very clear from the interviews that the dominant teachers' union, viz. South African Democratic Teachers Union (SADTU) plays a very activist and disruptive role in many of the schools. The following statements give an indication of the extent of SADTU's disruptive role in the appointment processes and the politicisation of schools:

Participant B Interview 2

Yes, I must say this in confidence, if you look at schools where, for example, the majority of the members belong to one union, including the principal, and only two or three belong to another union ... During the strikes, if the strikes were organised by a union for a day or two or three or more, then the learners are not going to be taught during that period.

...Now, for the past two, three months, those educators which are members of a union which is affiliated to COSATU, were not in the classrooms. You must look at the results this year; I think it is going to be adversely affected. That is why I am saying, in one way or the other, this union is having a political mandate from the ruling party or their union federation. So, therefore, whenever they come to school they want to politicise everybody, even political leaders. That is why you find that the school governing bodies today are operating under very, very tremendous pressure from the unions. Because if you look at this year in terms of learners here, all the unions were involved. Now you can see that we are going in a direction where our education is politicised. (Ln: 111-129).

In addition, the disquieting statistic of Taylor (2006:2) that approximately 80% of the schools in South Africa are essentially dysfunctional, confirms that effective and proper education is not taking place in these schools. The question arises why the departments do not address this desperate situation more emphatically. Emphatic action against unlawful or undisciplined behaviour educators and union officials would include steps such as criminal prosecution and disciplinary action by the employer. Although it is obviously impractical to discipline all the dysfunctional educators, taking steps against the worst offenders would undeniably send a message that such behaviour will not be tolerated. Consistent and fair application of the law affirms the rule of law and act as a deterrent for unacceptable behaviour.

Taylor (2006:22) found that policies and administrative attempts to improve accountability, such as implementing Standard Based Assessment, capacity building measures and support packages, have had no effect on dysfunctional schools. Fleisch (2006:369-382) reported that the increased monitoring and surveillance that accompanied the Education Action Zone (EAZ) intervention programme for profoundly dysfunctional schools in the Gauteng province, resulted in substantial and consistent improvements. However, the EAZ strategy was criticised by SADTU as a crack unit to bully schools and as a result the imposition of bureaucratic accountability waned (Fleisch, 2006:371). In February 2006 both the national Minister and the Gauteng MEC for education threatened to close dysfunctional schools, but after protests from learners and certain unions, these forewarnings were not followed through (Taylor, 2006:22). Jansen (2007:5) advocated the reinstatement of the inspection system, strict contractual accountability for every educator and the replacement of school principals in dysfunctional schools.

Despite these recommendations the departments of education have been reluctant to take strong emphatic action to enforce compliance. This reluctance suggests a profound misunderstanding of the principle of the rule of law. In other words, it is contended that by overtly allowing anarchy (lawlessness) and systematised unprofessionalism to prevail in schools, the education departments exhibit a fundamental misunderstanding of the democratic imperative to apply the law with relentless rigour in order to maintain a state based on the rule of law. To put it differently, if the departments of education (and its officials) overestimate the political role that a teachers' union should be allowed to play, and if the departments of education misconceive the extent of the labour rights of educators, then the inevitable result is overpoliticisation of schools and systematised unprofessional conduct or dysfunctional behaviour by educators. Of course, a democracy is not anarchy, because the people agreed to and established the laws of the country.

The political action by labour unions during the struggle against apartheid was understandable, because the previous regime was not democratic. However, with the attainment of democracy, political activism should no longer be the role and function of unions and their power should be restricted to labour matters. Therefore, by erroneously endorsing, permitting or condoning political activism by educator unions in schools, the education departments are acting contrary to the democratic principle of the rule of law.

The second indication of a misapplication of democratic principles is the failure to promote linguistic diversity and mother tongue instruction. Despite the finding that 85.38% of the respondents agreed that home language education is in the best interest of the learners, the Setswana et al. language group was patently against the tolerance and accommodation of Afrikaans single medium schools. The examples of court cases (Laerskool Middelburg v. Departementshoof, Mpumalanga Departement van Onderwys, 2003; Governing Body of Mikro Primary School v. Western Cape Minister of Education, 2005; Laerskool Seodin v. Department of Education, Northern Cape Province, 2005; Hoërskool Ermelo v. Departementshoof, Mpumalanga Departement van Onderwys, 2009) and the statements by senior education officials in the qualitative study confirm the pattern of advancement of a policy to promote uniform English medium instruction at the expense of Afrikaans and African languages. Thus, the official policy of promotion uniformity at the expense of diversity, is a misapplication of section 30 of the Constitution and article 1 of the international treaty, the Convention on Prevention of Discrimination in Education, which stipulate the protection of diversity.

Bureaucracy constrains the authority of school governing bodies

Parry & Moran (1994:48) affirm that in principle the whole population must acquire a set of democratic and educational attitudes in order to minimise constraints to democracy in education. In accordance with this principle, it is suggested that a change in democratic attitudes is necessary for some education leaders and education officials. The examples of the following court cases provide substantiation of the fact that provincial and national administrators at times display attitudes averse or indifferent to the democratic principles of responsiveness, accountability and transparency. This constrains participation by school governing bodies.

The case of Settlers Agricultural High School v. Head of Department of Education, Limpopo Province, 2002 is illustrative of the manner in which the education officials bureaucratically disregarded the democratic authority of the school governing bodies. This matter involved the appointment of a principal to a vacant post. The school governing body had duly complied with all the legal procedures and recommended that Mr V, a white Afrikaans candidate, be appointed in first choice of preference. However, the Education Department appointed the second candidate on the shortlist, Mrs M., because the departmental employment equity plan favoured a black female candidate as an affirmative action appointment. The Education Department contended that it could not be expected to simply "confirm and rubberstamp" a recommendation of a governing body, but that it was obliged to take requirements of employment equity into consideration. The court rejected the arguments of the department and upheld the recommendation and contentions of the school governing body.

In Despatch High School v. Head of Department of Education, Eastern Cape, 2003 the Eastern Cape High Court voiced its displeasure at the way in which the education department in that province had dealt with a complaint against a principal who had stolen a school cellphone and had lied about it. The court specifically stated that the manner in which the respondent dealt with the concerns of the governing body regarding the continued presence of the principal at the school was far from satisfactory. The court faulted the Head of Department of Education for displaying indifference to the "understandable concerns" of the governing body. Had the Head of Department complied with the democratic obligation to be responsive to public involvement through deliberation, the need for the school to resort to litigation might well have been averted.

In the case of Suid-Afrikaanse Onderwysunie v. Departementshoof Departement van Onderwys, Vrystaat, 2004 (Translation: South African Education Union v Head of Department of Education, Free State province) the authority devised a scheme to dismiss 1,200 temporary educators (Beckmann, 2007:5). The administratively unjust and unlawful decision of the Free State education authority was set aside by the court. The judge, Hattingh J, castigated the officials of the Free State provincial department of education for ignoring the principles of legality and administrative justice in the way they treated the educators.

The case of Maritzburg College v. Dlamini, Mafa and Kondza, 2005 was a clear example of the unresponsiveness and poor quality of education administration at the provincial level. In this case, the school governing body held a proper and fair hearing and decided to recommend expulsion of two ill-disciplined learners to the Head of the Department of Education, KwaZulu-Natal. Despite numerous letters, telephone calls from the governing body and a meeting with the Head of Department, he failed to come to a decision on the expulsion of the learners for 21 months. Eventually, out of sheer desperation the school governing body approached the High Court for a declaratory order. The Court criticised the unresponsive bureaucratic attitude of the official and upheld the decision of the governing body. Punitive costs were awarded to the school.

Thesecases confirmthat bureaucratic unfairness, unresponsiveness, non-transparencyand injustice results in unduly constraining the authority of school governing bodies.

Poor parental participation the result of inadequate participation

Although many factors such as poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, low competency levels and lack of transport result in inadequate parental participation, poor parental participation is also partially attributable to undemocratic actions such as over-politicisation of school governing bodies, the increased centralisation and bureaucratic decision-making and misapplication of democratic principles. This statement will be validated in the following paragraphs.

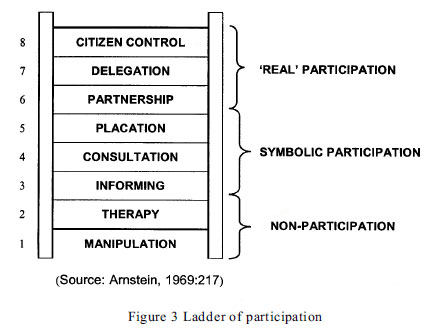

Poor parental participation is often attributable to misunderstanding of participatory democracy. Arnstein (1969:217) described a "ladder of participation" in terms of which the higher level on the ladder corresponds with a higher level of participation (see Figure 3).

This ladder of participation affirms that certain forms of communication such as placation, consultation, informing, therapy and manipulation do not result in true participation. In fact, the symbolic forms of participation spuriously convey a false message of involvement, which ultimately discourages or dissuades parents. In order to promote involvement and improve education, education administrators, education leaders and school governing bodies should utilise multiplicitous modes of enabling real parental participation such as meetings, public hearings, public comment processes on policies, voting, campaigning, group activities, liaison with representatives and officials, protesting, petitioning, fund-raising, canvassing and boycotting (Parry & Moyser, 1994:46). School governing bodies should contribute to the democratisation of school education by exercising local authority on matters such as school finances, school ethos and culture, policydecisions about networksinvolvingprivate-public partnerships and collaboration with community organisations (Rossouw & Van Rooyen, 2007:20).

The findings of the qualitative study clearly confirmed that many school governing body members misunderstand the role of the school governing body to be a political forum where political rights are exercised (Interview 2, Ln:133-137; Interview 3, Ln:210-218 and Interview 6, Ln:20-36). The parents often misconceive participatory democracy for political democracy and as a result schools become a playing field to further political ambitions of the cadres of the ruling party and to politicise schools (Ln:210-218).

Increased centralisation and bureaucratic decision-making

Another reason for poor participation is the absence or gradual erosion of real participation. Many compromises regarding the powers of governing bodies have been significantly altered in an apparent reduction of powers of governing bodies through a series of amendments of the Schools Act (Beckmann, 2007:13).Thesesuggest a recentralisation of decision-making powers in respect of curriculum content, recommendations of staff for appointment, levying of school fees and the utilisation of school funds (Beckmann, 2007:14). Malherbe (2006:247) argued that the formal structures for co-operation and negotiation between the national and provincial spheres with regard to education have become "little more than a one-way traffic system" as a result of centralisingtendencies and policies of national government. Van Deventer (1998:51) contended that the extent of the state's prescriptive regulations and intervention of all aspects of admission, language, and religious policies, norms and standards for funding and financial administration, expulsion and code of conduct guidelines in reality does away with any real partnership or power-sharing.

Generally speaking it is advantageous to have an education system with both centralised and decentralised features. The centralisation of matters and policies of general purport such as curriculum content, assessment standards, school financing- and educator provision formulae enhances the effective functioning of the education system. However, this should be balanced with the necessity to decentralise decision-making power in order to accommodate local variations and the specific requirements of each school community. The trend towards increased centralisation of decision-making power of local school governing bodies is confirmed by this study as the majority of the senior education officials (73.3%), school principals (59.7%), and 50.7% of the school governing body chairpersons regarded the education system as simultaneously centralised and democratic. Increased centralisation by virtue of politically motivated assumption of local decision-making authority undermines the participatory design of the South African Schools Act.

Misapplication of democratic principles

The case of Head of Department, Mpumalanga Education Department v. Hoërskool Ermelo, 2009 involved a functional school governing body whose language and admissions policies conflicted with the central and provincial government's policies. The Department of Education removed the school governing body's function in terms of section 25 of the Schools Act in order to impose a change in language policy onto the school. Such instances of undemocratic misappropriation of the functions of school governing bodies by the Department of Education negate the democratic principles of subsidiarity and participatory democracy. In essence, the principle of subsidiarity entails that the responsibility and functions of lower spheres or levels in a systemor organisation must not be unlawfully usurped or misappropriated by higher levels of power (Carpenter, 1999:46). The Department of Education should, in principle, play a "subsidiary" role insofar as it should provide support and may only take over the functions of a school governing body if the latter is defunctive (Carpenter, 1999:46).

Parents, principals and administrators strongly in favour of decentralisation of school governance

In contrast to the argument by Soudien and Sayed (2004:106) that decentralisation has gone too far in the South African education system, the vast majority (96%) of the respondents to the quantitative study, including senior education officials, agreed that despite the shortcomings, parental participation improves school effectiveness and that the decentralised model of local school governance should continue. It should be borne in mind that the respondents were representative of the demography of North-West Province and included responses from rural, township, farm, and suburban schools. The majority of school principals (67.9%) and school governing body chairpersons (70.2%) were opposed to the suggestion that school governing bodies should be replaced by more centralised "Boards of Education"' in every district. The attitude of the majority of all the respondents was strongly against increased centralisation (88.9%), disagreed with suggestions to reduce parental participation (66.6%), and disagreed with the statement that the provincial education department should appoint educators (64.8%).

Recommendations

Democratisation of a society requires an inculcation of knowledge, values and attitudes into substantive democratic practice by means of education (Aspin, 1995:58). It was Thomas Jefferson, third American president, who said that if a nation expects to be uneducated and free, then it expects something that never was and never shall be (Blaug & Schwartzmantel, 2006). Dewey (1916:1-378), the pragmatist American philosopher and renowned educationalist, asserted that democracy shapes education and education, in turn, shapes democracy. This implies that the nature and practice of democracy in societal institutions, such as schools, must be congruent with the education that citizens receive; otherwise, the educative force of the real environment would counteract the effects of early schooling (Parry & Moran, 1994:48).

In order to address some of the undemocratic inclinations in the school governance system, it is contended that the theories of participative and deliberative democracy suggest outcomes that would improve the present system. Most of these recommendations are contained in the theory of deliberative democracy and are based on the democratic principles of responsiveness, accountability, common interest and justification of decisions through rational discourse. In this regard it is recommended that:

• The democratic principle of the rule of law should be vigilantly applied by addressing anarchic conditions at dysfunctional schools. This applies especially to over-politicised schools suffering under the political dominance of SADTU and incompetent educators;

• Inadequate knowledge of democratic principles constrains democracy. In order to allay the constraints of ignorance and misconceptions, over-politicisation of schools, absolute majoritarianism, homogenous hegemonyand single language dominance, it is recommended that education and training should be provided to all stakeholders in education. Universities, departments of education and school governing bodies all have a significant role to play in this regard;

• Civic attitudes of democratic citizens should ideally include the virtues of responsibility, obedience to elected leaders in authority, adherence to the law, tolerance of individual autonomy and private freedoms, courage and loyalty in times of strife, interest and participation in community and state affairs by frequent debating and voting on issues. However, in the modern era, the content of what it means to be a good citizen has become shallow and the power of political and socio-economic rights does not go hand-in-hand with the inherent quality and commitment to noble civic attitudes (Cunningham, 2002: 111). To improve noble civic attitudes of democratic citizens the education and cultivation of an open, rational approach to deliberation is recommended. By contrast, a closed approach constrains democracy by strategically advancing discussions with incorrect attitudes and hidden political agendas. Such closed attitudes are not committed to finding collective solutions;

• The deliberative remedies of structured accountability and shared responsibility aim to counteract self-interested decision-making by emphasising the common interest of all citizens. Structured accountability entails the establishment of formalised mechanisms and procedures such as inspections, audits, compulsory reporting and frequent feedback to the stakeholders to improve responsiveness;

• Democratic values and attitudes such as respect for human dignity, the achievement of equality, the advancement of freedoms, tolerance, responsiveness and accountability cannot be instilled by merely enforcing policies and the law, but also need to be taught and demonstrated by example and application. It is essential to continuously cultivate values that are required for democracy to succeed. These values are:

- Rationality: procedures based on justifiable reasons in which the fundamental principles of morality are implicit;

- Equality: All people are presumed equal until justifiable and reasonable grounds are given for treating someone or some group differently;

- Freedom: All people are considered to be free until good reasons are given for constraints to be applied or liberty to be limited;

- Tolerance: The right to be different and for people to chose their own life-options is respected insofar as it does not unjustifiably or unreasonably infringe the rights of others;

- Respect: The dignity of all people and the communal and civic interests of society are considered more important than the self-interest of the individual.

The remedies to improve democratic values are the protection of constitutional rights through fair and just adjudication and the cultivation of tolerance for diversity. The commitment to fair governance should avoid enforced subjugation, irrationality, inequality, disrespect and bias;

• In order to increase authentic parental participation it is recommended that the National Education and Training Council, which is a participative forum, must be populated by the Minister of Education. Also, additional deliberative and participatory forums such as parent forums and Area School Boards should be established and based on the open, rational approach of deliberative and participatory democracy.

Obviously, the implementation of these recommendations would entail that the education departments would have to commit to improving participation; addressing the tendency to centralise the education system and amending legislation to provide for additional deliberative forums.

Conclusion

This discussion has demonstrated that some of the challenges in the education system are partly attributable to misconceptions of democracy, misapplications of legal and democratic principles and systemic weaknesses in the traditional models of democracy. Democratisation of the education system should be improved by training all stakeholders in education, by improving authentic participation and by applying the principles of deliberative democracy. In order to improve school governance and the education system, it is recommended that inculcation of essential knowledge, values and attitudes to attain substantive democracy should be based on the theory of deliberative democracy and the principles of responsiveness, accountability and justification of decisions through rational discourse.

Note

1. North-West Province is divided into the following administrative districts: 1 Brits 2 Temba 3 Mabopane 4 Moretele 5 Moses Kotane 6 Kgetleng River 7 Rustenburg 8 Kagisano Molopo 9 Gaseganyana 10 Greater Taung 11 Moshaweng 12 Taledi 13 Lichtenburg 14 Greater Delareyville 15 Zeerust 16 Setlakgobi 17 Matlosana/Klerksdorp 18 Maquassi Hills 19 Potchefstroom.

References

Adams F & Waghid Y 2005. In defence of deliberative democracy: Challenging less democratic school governing body practices. South African Journal of Education, 25:25-33. [ Links ]

Alexander N 2003. Language Policy, Symbolic Power and the Democratic Responsibility of the Post-apartheid University. Pretexts, literary and cultural studies, 12:170-190. [ Links ]

Arnstein SR 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35:216-224. [ Links ]

Aspin DN 1995. The Conception of Democracy: A Philosophy for Democratic Education. In: Chapman J, Froumin I & Aspin D (eds). Creating and Managing the Democratic School. London: Washington, DC: The Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Beckmann J 2007. Aligning School Governance and the Law: Hans Visser on Education Cases and Policy. Paper delivered in memory of the late Prof PJ (Hans) Visser, 27 July 2007, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Blaug R & Schwarzmantel J (eds) 2000. Democracy: A reader. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Chapman J, Froumin I & Aspin D (eds) 1995. Creating and managing the democratic school. London: The Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Carpenter G 1999. Cooperative Government, Devolution of Powers and Subsidiarity: the South African Perspective. Seminar report on sub-national constitutional governance, UNISA, 16 June 1998. Konrad Adenhauer Foundation. [ Links ]

Chaskalson A 2009. Fourth round panel discussion held on 22 February 2010 during Constitutional week, hosted by the Democratic Government and Rights Unit, University of Cape Town. Accessed on 20 August 2010 from http://www.dgru.uct.ac.za/dialogue/podcasts. [ Links ]

Cunningham F 2002. Theories of Democracy: a critical introduction. London, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

De Groof J, Bray E, Mothata S & Malherbe R (eds) 1998. Power-sharing in Education: Dilemmas and implications for Schools. Leuven: Acco. [ Links ]

Dewey J 1916. Democracy and education: an introduction to the philosophy of education (1966 printing). New York, NY: Free Press. [ Links ]

Ellis SM 2008. Interviews, 15 March 2008; 13 to 30 October 2008, 17-29 November 2008. North-West University: Statistical Consultation Services. [ Links ]

Eriksen EO & Weigard J 2003. Understanding Habermas - Communicating Action and Deliberative Democracy. London, New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Fishkin JS & Laslett P (eds) 2003. Debating Deliberative Democracy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Fleisch B 2006. Bureaucratic accountability in the Education Action Zones of South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 26:369-382. [ Links ]

Gallie C 2007. If you want to solve your discipline problems in schools, dare to 'fix-up' the adults first!. Paper delivered at the International Conference on Perspectives on Learner Conduct, North-West University, Potchefstroom, 4 April 2007. [ Links ]

Grant Lewis S & Naidoo J 2004. Whose Theory of Participation? School Governance Policy and Practice in South Africa. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 6:100-111. [ Links ]

Habermas J 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributing to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. (Transl. Rheg W). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Held D 1987. Models of Democracy. Oxford: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Jansen J 2007. If I were Minister of Education ... Key priorities to turning public schooling around. Improving Public Schooling Seminars. Pretoria: Umalusi. [ Links ]

Karlsson J 2002. The role of democratic governing bodies in South African schools. Comparative Education, 38:327-336. [ Links ]

Kotze D 2004. The nature of democracy in South Africa. Politeia, 23:22-36. [ Links ]

Kymlicka W 2002. Contemporary Political Philosophy: An Introduction, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Leedy PD & Ormrod JE 2005. Practical research: planning and design. International edition. Upper Saddle, NJ: Pearson Educational International. [ Links ]

Malherbe R 2006. Centralisation of Power in Education: Have Provinces become National Agents? Journal for South African Law, 2:237-252. [ Links ]

Maree K (ed.), Creswell JW, Ebersöhn L, Eloff I, Ferreira R, Ivankova NV, Jansen JD, Nieuwenhuis J, Pietersen J, Plano Clark VL & Van der Westhuizen CJ 2007. First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Merriam S 2008. Qualitative Research Methods Workshop manual. Manual for training workshop, North-West University, Potchefstroom campus, 9-19 June. [ Links ]

Myburgh J 2004. Ideological battle over meaning of democracy. Focus, 34. Available online at http://www.hsf.org.za/focus34/focus34myburgh.html. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen IJ (ed.) 2003. Aspects of Education Law, 3rd edn. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Parry G & Moran M 1994. Democracy and democratization. London, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Parry G & Moyser G 1994. More Participation, More Democracy? In: Beetham D (ed.). Defining and Measuring Democracy. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Pateman C 1970. Participation and Democratic Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Popper KR 1971. The open society and its enemies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

SayedY 1999. Discourses of the policy of Educational Decentralisation in South Africa since 1994: an examination of the South African Schools Act. Compare, 29:141-152. [ Links ]

Schumpeter J 1943. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. London: Allen & Unwin. [ Links ]

Soudien C & Sayed Y 2004. A new racial state? Exclusion and inclusion in education policy and practice in South Africa. Perspectives in Education, 22:101-115. [ Links ]

Squelch JM 1998. The establishment of new democratic school governing bodies: co-operation or coercion. In: De Groof J, Bray E, Mothata S & Malherbe R (eds). Power-sharing in Education: Dilemmas and implications for Schools. Leuven: Acco. [ Links ]

Steyn JC, Du Plessis WS & De Klerk J 1999. Education for democracy. Durbanville:Wachwa Publishers. [ Links ]

Tarrant JM 1989. Democracy and education. Avebury: Aldershot. [ Links ]

Taylor N 2006a. Focus on: challenges across the education spectrum. JET Bulletin, 15:1-9. [ Links ]

Taylor N 2006b. Accountability and support in school development in South Africa. Paper presented to the 4th Sub-regional Conference on Assessment in Education hosted by Umalusi, Pretoria, 26-30 June. [ Links ]

Tocqueville A 1966. Democracy in America. (Transl. G Lawrence, JP Mayer & M Lerner). New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Tulis JK 2003. Deliberation between Institutions. In: Fishkin JS & Laslett P (eds). Debating Deliberative Democracy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

United Nations 1960. The Convention Against Discrimination in Education. New York: United Nations. [ Links ]

Van Deventer HT 1998. The value and practice of real partnership between learners, educators and the State as a means of sharing power on the institutional level of education. In: De Groof J, Bray E, Mothata S & Malherbe R (eds). Power-sharing in Education: Dilemmas and implications for Schools. Leuven: Acco. [ Links ]

Van Rooyen J & Rossouw JP 2007. School Governance and management: Background and Concepts. In: Joubert R & Bray E (eds). Public School Governance in South Africa. Pretoria: Centre for Education Law and Policy. [ Links ]

Wiechers M 2008. Comments during the radio talk show: Kommentaar on 19 October 2008. Radio Sonder Grense. SABC, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Wiklund H 2005. Democratic deliberation - In search of arenas for democratic deliberation: a Habermasian review of environmental assessment. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 23:281-292 [ Links ]

Legislation

South Africa 1996a. National Education Policy Act 27 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

South Africa 1996b. South African Schools Act 84 of 1996. Number 86. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

South Africa 1996c. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 102 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

South Africa 1996d. Convention against Discrimination in Education. http://www.dfa.gov.za/foreign/Multilateral/inter/index/html. Accessed 5 January 2008. [ Links ]

South Africa 2000a. African [Banjul] Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights. http://www.dfa.gov.za/foreign/Multilateral/inter/index/html. Accessed 5 January 2008. [ Links ]

South Africa 2004. Convention on the Rights of the Child. http://www.dfa.gov.za/foreign/Multilateral/inter/index/html. Accessed 5 January 2008. [ Links ]

Table of cases

Governing Body, Mikro Primary School, and another v. Minister of Education, Western Cape, and others. 2005 (3) SA 504 (C).

Ermelo High School and Another v. Head of Department, Mpumalanga Department of Education and others. Case No. 240/2009 CC.

Laerskool Middelburg v. Departementshoof, Mpumalanga Departement van Onderwys. 2003 (4) SA 160 (T).

Maritzburg College v. Dlamini NO, and others. 2005 JOL 15075 (N).

Minister of Education, Western Cape, and others v. Governing Body of Mikro Primary School, and another. 2005 (3) SA 436 (SCA).

Pearson High School v. Head of the Department Eastern Cape Province and others. 1999 JOL 5517 (Ck).

Seodin Primary School and others v. Northern Cape Department of Education and another. Unreported Case No. 117/2004 (NC).

Settlers Agricultural High School & the Governing Body Settlers Agricultural High School v. The Head of Department: Department of Education, Limpopo Province. Case No. 16395/02 (T).

Simela v. MEC for Education, Eastern Cape. 2001(9) BLLR 1085 (LC).

Suid-Afrikaanse Onderwysunie v. Departementshoof Departement van Onderwys, Vrystaat. 2001 (3) SA 100 (FS).

Authors

Marius Smit is an Associate Professor in the Department of Education Law at the North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, and an Attorney. His research interest focuses on education law and he is widely published in this field.

Izak Oosthuizen is Professor in the Faculties of Education, North-West University. His research focus has been on education law for the past 25 years.