Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.30 n.4 Pretoria Jan. 2010

ARTICLES

School effectiveness: conceptualising divergent assessment approaches

RJ (Nico) Botha*

ABSTRACT

Studies on school effectiveness have dominated the literature of education management and administration for some time. According to the literature, these studies have two distinct aims: firstly, to identify factors that are characteristic of effective schools, and secondly, to identify differences between education outcomes in these schools. The choice and use of uniformed outcome measures has, however, been open to debate in many areas of education research. One of the touchstones for effective schools is the impact on learners' (scholars or students) education outcomes. Researchers into school effectiveness, however, continuously aim to clarify the dilemma with regard to learners' education outcomes. In parallel with this has been a call for schools to be more accountable, which in many cases leads to school effectiveness being judged on academic results, while other contributing factors are ignored. Apart from these studies, the uniform assessment of effectiveness in the school context has recently also received attention. This article, descriptive and narrative in nature and based on a literature study, offers a dynamic perspective on the assessment of school effectiveness and concludes with conceptualisation and analysis of three different, divergent approaches to measuring or assessing effectiveness of schools.

Keywords: assessment; assessment approaches; effectiveness; school effectiveness; studies of school effectiveness

Introduction

During the past 20 to 30 years there has been a major shift towards allowing educational institutions greater self-management and self-governance in a drive to improve school effectiveness (cf. Cohen, March & Olsen, 1972; Cohen, 1982; Conley, Schmidle & Shedd, 1988; Gurr, 1996; Dimmock & Wildley, 1999; Gray 2004). This trend has become evident in a variety of forms in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and parts of the United States of America (cf. Murphy & Beck, 1995; Johnston, 1997; Taylor & Bogotch, 2004; Petty & Green, 2007).

In spite of its widespread practice and implementation of these and other more recent initiatives to enhance school effectiveness in schools, no clear or uniformly accepted set of guidelines or assumptions with regard to the assessment of school effectiveness exists. There is, according to Brouillette (1997:569), "no set of shared assumptions about the actual evaluation on school effectiveness". To date, most of the evaluative work on school effectiveness has been, according to Giles (2005), conducted as part of policy research, and has tended to focus on monitoring implementation guidelines and using this information to identify features of successful school development plans (SDPs).

From an evaluation perspective, the logic of this approach is to teach what successful school management teams (SMTs) do in terms of effective SDPs and then to implement the same SDP to increase school effectiveness. There are however other, more scientific, ways to measure effectiveness in the schooling system.

Problem statement

The search for effective schools is one of the main education reform initiatives taking place in many countries today (cf. Petty et al., 2007). The critical question to be addressed in this study is: How can we assess school effectiveness in a uniform manner? Academic output measures have been widely used to identify good practices in schools. There is, however, a need for further measures of school effectiveness which capture more of the school processes and measure a broader range of outcomes. Some studies have indeed identified such measures (cf. Creemers, 2002; Kyriakides & Tsangaridou, 2008) and due to these developments in the area of measurement, researchers are constantly undertaking studies on school effectiveness looking at the broader range of the school curriculum (cf. Kyriakides & Creemers, 2008a). These indicators may in the future help to provide a wider range of measures for school success and effectiveness, thus better capturing what schools do.

In this article three different, coherent approaches to the assessment of school effectiveness will be presented and conceptualised to integrate both older and recent research on school effectiveness. In this process, I first conceptualise and explore the concept of school effectiveness and then present, discuss, and analyse the approaches to school effectiveness.

Conceptualising school effectiveness

The concept 'effectiveness' refers to an organisation accomplishing its specific objectives (Beare, Caldwell & Millikan, 1989:11). School effectiveness therefore means 'the school accomplishes its objectives'. School effectiveness can therefore be regarded as a distinct characteristic of an effective school.

The concept 'school effectiveness' can, however, mean different things and this has lead to a global debate around the concept (Mortimore, 2000). According to Sun, Creemers and De Jong (2007), studies of school effectiveness have two distinctive aims: firstly, to identify factors that are characteristic of effective schools, and secondly, to identify differences between education outcomes in these schools. The choice and use of outcome measures has been open to debate in many areas of education research (Sun et al., 2007). One of the touchstones of effective schools is the impact on learners' education outcomes (i.e. test or examination results obtained during formal assessment). In this regard, Bennet, Crawford and Cartwright (2003:176) define an effective school as "a school in which students progress further than might be expected".

Researchers into school effectiveness continuously aim to clarify the dilemma with regard to learners' education outcomes (cf. Sun et al., 2007 and Petty et al., 2007). A long-standing problem in this regard has been to find ways to measure learner progress or achievement that identifies the school's contribution separately from other factors such as learner ability, background and socio-economic environment. In parallel with this has been a call for schools to be more accountable, which in many cases leads to school effectiveness being judged on academic results, while other contributing factors are ignored.

As a result, academic outcomes, usually measured by test and/or examination results, have continued to dominate, while other outcome measures have been neglected or used to a lesser extent. Gray (2004:187) stated in this regard: "Examination results are a measure of academic learning but do not give the whole picture with regard to the effectiveness of a school academically, and give little information about other outcomes".

Morley and Rassool (1999) attempt to highlight the fact that school effectiveness as a paradigm is based on three distinct discourses, namely, leadership, management and organisation. Organisation of the school often has a predestined structure prescribed by the education authorities. The effectiveness of the school could be imposed by the government by the design of evaluation tools such as checklists and inspection, which may not necessarily enhance effectiveness, but seek to determine learner attainment.

Conversely, Harris, Bennet and Preedy (1997) highlight the political nature of school effectiveness by noting that governments determine how schools should function because of the value-for-money idea. However, to counteract the dominance of the government view in the management of the school, aspects such as marketing and the role of the parents and school community are also dominant factors. School effectiveness could indicate how well the school is managed by the principal and how well parents and the community are involved. Apart from the fact that researchers are not always sure what outcome (or category) of school effectiveness to measure, the definition of school effectiveness may also vary from one person or source to the next. Another problem is that school effectiveness is often confused with an aspect such as school efficiency. To clarify the above, each term and category of school effectiveness should first be correctly conceptualised and defined.

For the purposes of this study, the term 'school effectiveness' refers to the "ratio of output to non-monetary inputs or processes" (Cheng, 1996:36) and includes, among other things, the number of textbooks, classroom organisation, professional training of teachers, teaching strategies and learning arrangements. The term "school efficiency", on the other hand, can be regarded as the "ratio between school output and monetary input" (Cheng, 1996:37).

Furthermore, we can distinguish between internal and external school effectiveness (Cheng, 1996). Internal school effectiveness can be regarded as the school's technical effectiveness if its outputs are limited to what happens in or just after schooling (e.g. learning behaviour, acquired skills and changes in attitude), while external school effectiveness can be regarded as the positive impact of the school's outputs on society or on individuals' lives (e.g. social mobility, earning power and work productivity).

However, more methodologically advanced studies conducted more recently (cf. Bressoux & Bianco, 2004; Kyriakides & Creemers, 2008b) have looked at the long term effects on schools and revealed that there is indeed a close relationship between these two criteria of school effectiveness. The assumption that there is a direct correlation between these two categories of school effectiveness (internal and external) is often problematic and misleading, since a school with a high degree of internal technical effectiveness may not necessarily have a high level of external societal effectiveness. In other words, effective teaching and learning in schools may not necessarily lead to high productivity if these skills are found to be outdated later in life. Ignorance of this complicated relationship and an overemphasis on one category of effectiveness over another is to be avoided (Cheng, 1996; Petty et al., 2007).

The reality, also, is that every school has to pursue multiple goals because "it works within multiple environmental constraints and time frames" (Hall, 1987:28). Because many public schools world-wide have limited resources, it is extremely difficult for any school to maximise its effectiveness, specifically with regard to scarce resources, in order to achieve its goals. In the process of pursuing multiple goals, every school experiences different pressures from the environment, and therefore each school develops different priorities and criteria.

A school may not be able to maximise its effectiveness in terms of all criteria at the same time, but it will be able to create harmony among all criteria in the long run. Cheng (1996:41) has stated in this regard: "School effectiveness may be the extent to which a school can adapt to internal and external constraints and achieve its multiple goals in the long run". In other words, it is possible for the different categories of school effectiveness to be compatible with each other and eventually to work in harmony if schools can learn, adapt and develop.

Another relevant concept related to the issue school effectiveness, is that of 'school improvement'. Although these concepts are widely regarded as not synonymous with each other, the literature draws a rather close relationship between the two concepts. According to Macbeath and Mortimore (2001), school effectiveness came into being as a result of inequalities in society, which sparked a move towards education for all. In fulfilling the goal of education provision for all, schools need to continually revise and improve their performance. Schools that are continually improving their performance gain confidence, are self-critical, and understand how people learn. This has lead to a general assumption that school improvement leads to school effectiveness, therefore one is tempted to conclude that the two concepts, however different, cannot be looked at in isolation as their goals and intentions are inseparable.

This varied contextualization of school effectiveness as discussed seems to expose a multiplicity of understandings which lead one to conclude that the definition of school effectiveness may not be conclusive as context plays an important role. However for the sake of this study school effectiveness will be assumed to mean the state at which the school functions properly in all respects and experiences high learner attainment.

These different categories of school effectiveness form the framework of the first approach to school effectiveness to be presented and discussed in the next section.

Assessment approaches to school effectiveness

It is clear from the above discussion that the formulation, definition and measurement of school effectiveness are complex issues. The question remains: what category of school effectiveness (what school inputs and outputs) should be measured, and how should school effectiveness be correctly defined? From an organisational perspective, there are many different approaches for the conceptualisation, formulation and measurement of school effectiveness. The following seven indicators form the framework of the first assessment approach, The Indicator Approach (TIA), and are based on earlier research into the issue of school effectiveness (Cameron & Whetten 1983; Nadler & Tush-man, 1983; Cameron, 1984; Hall, 1987; Caldwell & Spinks, 1992; Cheng, 1993:96):

The goal indicator:

This indicator assumes that there are clearly stated and generally accepted goals, relevant and important both to teachers and the school, for measuring school effectiveness, and that a school is effective if it can accomplish its stated goals within given inputs. These goals or objectives are quantifiable, are set by the authorities or school self and can be measured against predetermined criteria such as the objectives in SDPs and academic achievement in tests and/or examinations. This indicator is widely used in schools for evaluation purposes due to the fact that goals and tasks assigned to teachers are clear and specific, outcomes of teachers' performance are easily observed and the standards upon which the measurement of teacher effectiveness is based are clearly stated. A limitation of this indicator is its dependence on the quantifiable, which is often impossible to ascertain.

The external resource indicator:

This indicator assumes that because scarce and valued resource inputs are needed for schools to be more effective, the acquisition of resources replaces goals as the primary criteria of effectiveness. An example of this indicator is financial support from outside the school. This indicator is limited by its overemphasis on the acquisition of inputs from external sources and its failure to look at the efforts made by the school itself to maintain its effectiveness.

The internal process indicator:

This indicator assumes that a school is effective if its internal functioning is effective. Internal school activities are often taken as criteria for school effectiveness. This indicator includes aspects such as leadership, communication channels, participation, adaptability and social interactions in the school. Some of the disadvantages of this indicator are that it is difficult to monitor and that it overemphasises the means of obtaining school effectiveness.

The satisfaction indicator:

This indicator defines an effective school as one in which all the stakeholders are at least minimally satisfied. It assumes, therefore, that satisfying the needs of the principal, teachers, SMT, governing body learners and the public is the school's main task. Satisfaction is, according to this view, therefore the basic indicator of effectiveness. This indicator may, however, not be appropriate if the demands of the stakeholders are in conflict with each other.

The legitimacy indicator:

According to this indicator, a school is effective if it can survive undisputed and legitimate marketing activities. This indicator is applicable only if the school has had to strive for legitimacy in a competitive environment.

The organisational indicator:

his indicator assumes that environmental changes and internal barriers to school functioning are inevitable and that a school is effective if it can learn how to make improvements and adaptations to its environment.

The ineffectiveness indicator:

This indicator assumes that it is easier for stakeholders to identify and agree on the criteria of school ineffectiveness than on those of effectiveness. It is easier to identify strategies for improving school effectiveness by analysing school ineffectiveness rather than by analysing school effectiveness. This means that a school is effective if there is an absence of characteristics of ineffectiveness. This indicator includes aspects such as conflicts, problems, difficulties, weaknesses, poor performance and poor results.

It becomes clear that each of the indicators mentioned can be seen as closely related to the goal indicator. For example, the resource indicator is not different at all from the goal indicator but simply emphasizes the need for a school to encourage and expect from teachers to maximally exploit allocated resources and locate new resources.

These indicators for evaluation of school effectiveness, together with the two categories discussed earlier (internal and external), can consequently be integrated into an evaluative framework (TIA) (Figure 1) which provides a complete and consistent assessment of school effectiveness from seven different perspectives. It also determines the relationship between the seven indicators for school effectiveness and the two categories of school effectiveness.

In the context of this study, the concept of harmony means to be compatible, in agreement or unity with regard to an opinion or action (Wikipedia, 2010). The rows in TIA can be regarded as the 'model field' in the framework, and represent the various indicators for school effectiveness, described earlier, to the extent that they are consistent, compatible and in harmony or equilibrium with each other. The columns in TIA can be regarded as the 'category field' in the framework; these represent the two categories of internal technical school effectiveness and external societal school effectiveness, and show the extent to which these categories are consistent, compatible and in harmony or equilibrium with each other.

In terms of the concept of harmony in the evaluation framework, there are two levels that may contribute to maximising school effectiveness. On the horizontal level, 'category harmony' indicates the extent to which the two categories of school effectiveness are consistent and in harmony with each other. A high level of harmony in the category field indicates that the higher the effectiveness in one category, the higher the effectiveness in the other category. Of course, this implies that the lower the effectiveness in one category, the lower the effectiveness in the other. Ensuring harmony between the two categories of school effectiveness is therefore very important in pursuing maximum school effectiveness.

The vertical level of harmony can be described as 'model harmony', referring to the extent to which the seven different indicators' conceptions of school effectiveness are compatible and in harmony with each other. A high level of harmony indicates consistent and compatible, or at least not conflicting, indicators of effectiveness.

Empirical evidence from studies conducted on teachers' perceptions on effectiveness indicators (Teddlie & Reynolds, 2000; Kyriakides, Demetriou & Charalambous, 2006) have revealed the need to utilize multiple, not just single, assessment approaches as basis for the evaluation of school effectiveness. A concern or shortcoming in using only TIA is that different stakeholders, such as teachers with different concerns, perceptions and conflicting values, may use different indicators for the measurement of school effectiveness.

However, if the chosen indicators are in harmony with each other, they may be integrated. This Indicator Approach will provide then a complete and consistent evaluation tool for school effectiveness from different perspectives and may be used to ensure the harmony of indicators and categories of effectiveness in order to maximise school effectiveness. If the chosen indicators, however, are not in harmony, they cannot be integrated and school effectiveness cannot be maximised (Cheng, 1996).

Another major concern with TIA is that it can distort the system it is attempting to measure. A common example of this is where a teacher employs methods that are not pedagogically appropriate, while ignoring other, wider aspects of the educational process. In such a scenario the most effort is put into getting borderline learners to pass tests and examinations, while almost ignoring other, more capable, competent learners. This concern is, however, less likely to lead to counterproductive results. Such a teacher, it could be argued, attempting to improve results, is probably also improving the standard of education and therefore also the effectiveness of the school.

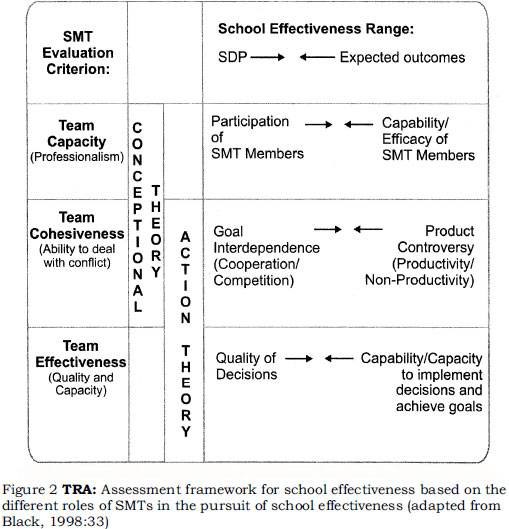

A second, alternative assessment approach, also based on earlier research (Deutsch, 1990; Tjosvold & Deemer, 1990; Wohlstetter, Smyer & Mohrman, 1994; Wohlstetter & Mohrman, 1996; Leithwood & Menzies, 1998; Black, 1998) is entirely different from the first approach. This approach, referred to as The Role Approach (TRA) (Figure 2), focuses on the different roles of SMTs in pursuing school effectiveness, and does not include or consider the various indicators/categories of effectiveness as conceptualised in the TIA.

This approach describes, among other things, how successful SMTs can affect change in schools and improve school effectiveness. TRA consists of three interrelated components that serve as evaluation or assessment criteria, each of which is associated with and linked to a series of characteristics that describe each criterion, namely:

Team capacity:

This criterion is characterised by features like sharing information, team member effectiveness, access to information, requisite knowledge and skills, participation in goal setting, participation in the development of strategies and a focus on complex rather than simple tasks.

Team cohesion:

This criterion is characterised by cooperative, competitive and autonomous goal interdependence (i.e. a common purpose and sense of interdependence) and productive controversy (i.e. pitching views against each other deliberately or learning to fight over issues) (Google Books, 2010).

Team effectiveness:

This criterion is characterised by the quality of decisions and the capacity to implement such decisions.

The criterion of team capacity refers to the professionalism of SMTs and the degree in which the school principal is capable of cooperating and exchanging ideas and information with SMTs (Wohlstetter et al., 1996). If school principals do not believe that team members are in control of their environment and capable of solving problems effectively, it is unlikely that they will relinquish their decision-making powers. According to Tjosvold et al. (1990), specific elements of this criterion include:

• information sharing within the SMT and between the team and the school principal

• SMT members' perceptions of member effectiveness

• access to information by SMT members

• requisite knowledge and skills of SMT members

• participation in goal setting by SMT members

• participation by SMT members in the development of task strategies

• quality of task strategies

• a focus on complex rather than simple tasks

The criterion of team cohesion refers to the SMT's ability to deal with conflict situations. Members of the SMT who can work with opposing points of view to improve the quality of decisions made are more likely to understand the source of the opposing views and to incorporate a range of ideas into any decision eventually made. This criterion also refers to members' perceptions of team goals and the degree to which they experience cooperative, competitive or autonomous goal interdependence (Wohlstetter et al., 1996).

The specific elements of this criterion were derived from the theories of "cooperative goal interdependence" and "productivity controversy" (Deutsch, 1990:82). As far as cooperative goal interdependence (i.e. a common purpose and a sense of interdependence upon each other) is concerned, Deutsch (1990) theorised that when people such as SMT members cooperate, they believe that their goals (and rewards) are the same and therefore they relate positively to each other. When one person achieves a goal, it is more likely that other team members will attempt to achieve theirs: one person's success helps others to also try to succeed, although the effectiveness of members of any organisation will ultimately differ.

However, when people work in competition it is because they believe their goals to be negatively related. When one person reaches a goal, it is less likely that others will reach theirs; one person's success therefore hinders the success of others. In this regard it should be borne in mind that competition between employees will never be eliminated as it is the individual that gets awarded under a performance management system and not the group. Goals and rewards can therefore never be separated (Deutsch, 1990).

Productive controversy, on the other hand, is related to personal dynamics in an organisation and is a form of conflict that occurs when ideas, information and opinions are incompatible with each other (Tjosvold et al., 1990). Product controversy relates to a sense of cohesiveness and unity among employers in an organisation and involves the pitching of views or ideas against each other deliberately or learning to fight over ideas when these are incompatible (Google Books, 2010:225).

When controversy is productive, SMT members are more likely to understand opposing points of view and arguments, fighting less over ideas and this is likely to result in better decision-making. When controversy is unproductive, people express their opinions with regard to incompatible ideas, but in a more closed-minded manner. Tjosvold et al. (1990:384) have reported that, in the case of unproductive controversy, SMT members often try to find "weaknesses in opposing arguments so they are better able to counterattack, undercut other positions, and make their own views dominate; relying on superior authority or other means to try to impose their solution". As a result, controversy creates polarisation and results in a low-quality decision which only the winners are committed to implementing. This seriously influences school effectiveness in general.

Tjosvold et al. (1990) reported furthermore that work settings or situations with cooperative goals, but conflicting ideas and opinions, were most effective when one was trying to understand the conflicting points of view in assessing effectiveness. Information acquired in competitive climates is less likely to be assimilated into decision outcomes as a result of the predominance of closed-minded attitudes and a disregard for the source of information. In the case of cooperative climates, however, there is more respect for SMT members and their ideas and, although conflict may occur, different ideas are more likely to be considered.

The criterion of team effectiveness refers to the quality of SMT decisions and their ability to develop and to implement task strategies to achieve the school's goals and objectives. Elements of this criterion include quality of decisions and the capacity to implement them.

The relationship between the three evaluation criteria was presented in TRA above. The main purpose of this approach, empirically tested by Black (1998), is to explain how an SDP is expected to work to improve change and school effectiveness. An additional advantage of this approach is that it also illustrates the link between an SDP and its expected outcomes. According to Black (1998:33) this approach has two components, namely, a "conceptual theory test" and an "action theory test", which are interdependent. The conceptual theory component of TRA tests the hypothesis that a decision from the SMT influences the behaviour of the target population. Based on the three components discussed above, the conceptual theory is therefore the relationship between team capacity and team cohesion. Team capacity, as described by the set of specific characteristics, is posited to affect team cohesion. In other words, SMTs with greater capacity will be more cohesive.

The action theory component of TRA tests the hypothesis that the SDP results in particular outcomes (or outputs). In the case of this approach, the action theory assumes that team cohesion, as described by the set of specific characteristics, results in team effectiveness. Teams with greater cohesion will therefore be more effective.

A concern with TRA is that it does not include or consider the various process indicators and categories of school effectiveness as conceptualised in the first approach (TIA). This could be problematic, as process indicators have an important role to play in school evaluation, as "they provide timely diagnostic information to enable improvement" (Petty et al., 2007:70).

Within the study of school effectiveness, such indicators may help to provide a wider range of measures of effectiveness than the usual outcome measures, thus capturing better what schools do. Another shortcoming in TRA could be its 'logical approach' (i.e. to learn what successful SMTs do in terms of effective SDPs and then to implement the same SDP to increase school effectiveness) as the same SDP could not always work in different schools.

In recent research on school effectiveness (Sun et al., 2007; Creemers & Kyriakides, 2008; Kyriakides et al., 2008a; Kyriakides et al., 2008b; Van Damme, Opdenakker & Landeghem 2008), the authors emphasise, among other things, aspects such as national goal setting in terms of learner outcomes (i.e. learner outcomes and school effectiveness is firmly embedded in its national context), pressure in the form of strong central control and school accountability, and strong support from the community as some of the contextual factors that influence the effectiveness of schools.

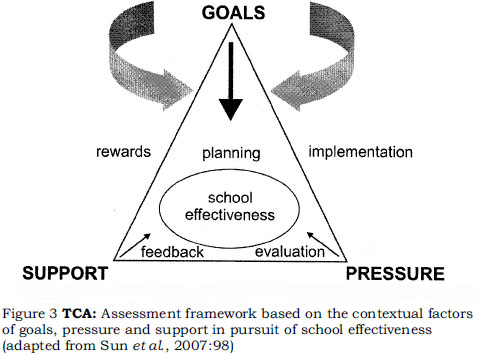

These three main effectiveness factors, namely, goals, pressure and support, form the basis of the third and last approach, referred to as The Contextual Approach (TCA) (Figure 3). This approach is related to the first two approaches discussed in terms of learners' outcomes, but differs in respect of the following contextual factors: the context of learners' outcomes, strong central control and accountability.

In this approach, the three main contextual factors of goals, pressure and support serve as indicators for school effectiveness. The major strength of TCA is that it may be less subject to incentives than many other process indicators, specifically those from TIA. This approach indicates, inter alia, that school effectiveness is firmly embedded in its national context, while national goals are twofold, namely, goals for learners' outcomes and goals for school improvement. A triangle was chosen as most suitable framework for TCA as it symbolises the important relationship between the three elements (Sun et al., 2007).

School effectiveness criteria for goals include national goal setting in terms of learner outcomes, while school effectiveness criteria for pressure include aspects such as strong central control, external evaluation and school accountability. Lastly, school effectiveness criteria for support include, inter alia, adequate time, financial and human resources as well as a culture of decentralisation (Van Damme et al., 2008).

Around the triangle in TCA, each of the three main contextual factors' research areas adds a continuous dynamic process element to the approach and indicates that the issue of school effectiveness can never be separated from the national context which provides goals, pressure and support. Although pressure and support are readily reconciled, they are also closely related. Although it may be regarded as threatening to the autonomy of the school and to school-based management per se, strong central steering along with external evaluation can contain elements of pressure as well as forms of support. While school effectiveness emphasises the importance of evaluation, feedback, and reinforcement, evaluation is seen as the key to effective schooling (Creemers, 2002).

Conclusion

The question of how to conceptualise school effectiveness is becoming a major concern in current debates on educational reform. The purpose of this research was to provide a quantitative measuring approach for school effectiveness. I have proposed three different comprehensive approaches, each with its own indicators, for assessing school effectiveness.

It must be emphasised in conclusion that these approaches were introduced in this study without any empirical evidence. This may be regarded as a shortcoming in this study and a prospect for future research. Another shortcoming may be the fact that the study could not precisely predict the expected outcomes, in terms of educational quality, of each of the approaches introduced here.

However, the approaches discussed build on previous evaluation research as indicated earlier. The results suggests the usefulness and validity of these approaches in measuring school effectiveness, which can lead to further research both refining and applying these approaches.

References

Beare H, Caldwell BJ & Millikan RH 1989. Creating an excelling school. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bennet N, Crawford M & Cartwright M 2003. Effective educational leadership. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. [ Links ]

Black S 1998. A different kind of leader. American School Board Journal, 185:32-35. [ Links ]

Bressoux P & Bianco M 2004. Long-term teacher effects on pupils' learning gains. Oxford Review of Education, 30:327-345. [ Links ]

Brouillette L 1997. Who defines democratic leadership? High school principals respond to school-based reforms. Journal of School Leadership, 7:569-591. [ Links ]

Caldwell B & Spinks J 1992. Leading the self-managing school. London: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Cameron KS1984. The effectiveness of ineffectiveness. Research in organizational behaviour, 6:235-285. [ Links ]

Cameron KS & Whetten DS 1983. Organizational effectiveness: a comparison of multiple models. New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Cheng YC 1993. Conceptualization and measurement of school effectiveness: an organizational perspective. Paper presented at the annual meeting of AERA, Atlanta. [ Links ]

Cheng YC 1996. A school-based management mechanism for school effectiveness and development. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 7:35-61. [ Links ]

Cohen M 1982. Effective schools: accumulating research and findings. American Education, 18:13-16. [ Links ]

Cohen M, March J & Olsen J 1972. A garbage can theory of organisational decision making. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17:1-25. [ Links ]

Conley SC, Schmidle T & Shedd JB 1988. Teacher participation in the management of school systems. Teachers College Record, 90:259-280. [ Links ]

Creemers PM 2002. From school effectiveness and school improvement to effective improvement. Research and Evaluation, 8:343-362. [ Links ]

Creemers PM & Kyriakides L 2008. The dynamics of educational effectiveness: a contribution to policy, practice and theory in contemporary schools. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Deutsch M 1990. Over fifty years of conflict research in social psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Dimmock C & Wildley H 1999. Conceptualizing curriculum management in an effective secondary school: a Western Australian case study. The Curriculum Journal, 6:297-323. [ Links ]

Giles C 2005. Site-based planning and resource management: the role of the school development plan. Educational Change and Development, 45-50. [ Links ]

Google Books 2010. Retrieved on 12 August 2010 from http://books.google.co.za/books?id=qLET6auSnl0C&pg=PA260&lpg=PA260&dq=Productive+controversy. [ Links ]

Gray J 2004. School effectiveness and the 'other outcomes' of secondary schooling: a reassessment. Improving Schools, 7:185-198. [ Links ]

Gurr D 1996. The leadership role of principals in selected schools of the future. Doctoral thesis. Melbourne: University of Melbourne. [ Links ]

Hall RP 1987. Organizations: structures, processes and outcomes. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Harris A, Bennet N & Preedy M 1997. Organizational effectiveness and improvement in education. Buckingham: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Johnston C 1997. Leadership and the learning organisation in self-managing schools. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Melbourne: University of Melbourne. [ Links ]

Kyriakides L & Creemers BPM 2008a. A longitudinal study on the stability over time of school and teacher effects on student learning outcomes. Oxford Review of Education, 34:521-545. [ Links ]

Kyriakides L & Creemers BPM 2008b. Using a multidimensional approach to measure the impact of classroom level factors upon student achievement: a study testing the validity of the dynamic model. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 19:183-205. [ Links ]

Kyriakides L, Demetriou D & Charalambous C 2006. Generating criteria for evaluating teachers through teacher effectiveness research. Educational Research, 48:1-20. [ Links ]

Kyriakides L & Tsangaridou N 2008. Towards the development of generic and differentiated models of educational effectiveness: a study on school and teacher Effectiveness in Physical Education. British Ed Research Journal, 34:807-838. [ Links ]

Leithwood K & Menzies T 1998. Forms and effects of school-based management: a review. Educational Policy, 12:325-346. [ Links ]

Macbeath J & Mortimore P 2001. Improving schools' effectiveness. Philadelphia: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Morley L & Rassool N 1999. School effectiveness fracturing the discourse. London: Falmer Press, Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Mortimore P 2000. Globalization, effectiveness and improvement. Paper read at the 13th annual meeting of the International Congress for School Effectivness and school improvement, Hong Kong, January 4-8. [ Links ]

Murphy J & Beck I 1995. School-based management as a school reform: taking stock. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. [ Links ]

Nadler DA & Tushman ML 1983. Perspectives on behaviour in organizations. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Petty NW & Green T 2007. Measuring educational opportunity as perceived by students:a process indicator. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 18:67-91. [ Links ]

Sun H, Creemers BPM & De Jong R 2007. Contextual factors and effective school improvement. School Effectivenss and School Improvement, 18:93-122. [ Links ]

Taylor DL & Bogotch IE 2004. School-level effects of teachers' participation in decision-making. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 16:302-319. [ Links ]

Teddlie C & Reynolds D 2000. The International Hanbook of School Effectiveness Research. London: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Tjosvold D & Deemer DK 1990. Effects of controversy within a cooperative or competitive context on organisational decision-making. Journal of Applied Psychology, 3:376-386. [ Links ]

Van Damme J, Opdenakker M & Van Landeghem G 2008. Educational effectiveness: an introduction to international and Flemish research on schools, teachers and classes. Leuven: Acco. [ Links ]

Wikipedia 2010. Retrieve on 12 August from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/harmony. [ Links ]

Wohlstetter P, Smyer R & Mohrman S 1994. New boundaries for school-based management: the high involvement model. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 16:268-286. [ Links ]

Wohlstetter P & Mohrman S 1996. Assessment of school-based management. Office of Educational Research and Improvement, US Department of Education, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. [ Links ]

Author

RJ (Nico) Botha is Professor in Education Management in the School of Education at the University of South Africa. His fields of specialisation are educational leadership, comparative and international education. He has more than 20 years lecturing experience.