Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.30 n.4 Pretoria Jan. 2010

ARTICLES

The perceptions of teaching staff from Nigerian independent schools of a South African professional development workshop

Trudie Steyn*

ABSTRACT

There is widespread agreement that professional development (PD) is the best possible answer to meeting the complex challenges in education systems. Studies on educational effectiveness identify the link between quality teachers and their PD. The purpose of this exploratory study was to determine the perceptions of Nigerian delegates from independent schools of the effectiveness of a training programme conducted by academic staff at the University of South Africa (Unisa). A mixed-method approach was adopted in two similar workshops. In March (2008) (Phase 1), quantitative data were collected and, in October 2008 (Phase 2), qualitative data were collected. The results reveal delegates' experiences of the quality of the presentations, the content and learning experience, the extent to which the expectations of the delegates were met, the application possibility and relevance of the workshops to educational practice and the needs experienced in Nigerian schools and recommendations for future workshops.

Keywords: Nigerian education system; Nigerian independent schools; professional development; school management training; workshops

Introduction

It is widely accepted that global societal changes demand that all professionals and organisations develop in order to meet the challenges and cope with the changes that are rapidly taking place in their environments (Retna, 2007:127; Vemiæ, 2007:209). The teaching profession is no exception. There is widespread agreement that professional development (PD) is the best possible answer to meet complex challenges and benefit the individual and the school system (Boyle, Lamprianou & Boyle, 2005; Desimone, Smith & Ueno, 2006; Nielsen, 2005; Moswela, 2006; Van Veen & Sleegers, 2006; Vemiæ, 2007:209). The pressing need for quality staff to meet educational goals for sustainable development is particularly important in developing countries (Ololube, 2008:44; Garuba, 2004:202).

The research literature on educational effectiveness clearly identifies the dependancy between quality teachers and their professional development since teachers are called up to take action as change agents (Doring, 2002:1; Meiers & Ingvarsin, 2005:42; Teachers for the 21st Century - Making the Difference, 2008). A crucial factor for success appears to be the ability of staff at all levels to learn and be receptive in their work (What is a learning organisation?; Lee & Roth 2007; Moswela 2006). The necessity for continuous PD is succinctly supported by Doring (2002:2): "... the fact that teachers learn throughout their professional life is beyond argument". Other studies confirm the significance of professional development, "where it is identified and implemented within the school context to meet the needs of their teachers and students, for the continuous improvement of professional practice" (Teachers for the 21st Century - Making the Difference, 2008). Sparks (2003) and Van Eekelen, Vermunt and Boshuizen (2006) believe that effective PD programmes will deepen staff's understanding, transform their assumptions and beliefs, and lead to continuous classroom actions that change their practice.

When military rule ended in Nigeria in 1999, a democratically elected government came into power and there was considerable decentralisation of administrative and financial responsibilities (Ikoya & Onoyase, 2008:11; Okoroma, 2006:255; Geo-Jaja, 2004:317). Education was part of this widespread reform. However, education for sustainable development in developing countries requires "a life-wide and life-long endeavour" that challenges staff and schools to meet global aims (Ololube, 2008:44).

In Nigeria, the decentralisation of education comprises a mix of deconcentration and delegation of authority (Geo-Jaja, 2004). The central government determines the school curriculum, teacher compensation, budget allocation and access to education (Geo-Jaja 2004). Studies by Ogunyemi (2005), Osunde and Omoruyi (2005), Osunde and Izevbigie (2006) and Garuba (2004) unfortunately find that poor working conditions as well as society's negative influence on the education system are fundamental factors influencing the quality of Nigerian teachers and their low status in Nigeria. A study by Ikoya and Onoyase (2008) also points to the ineffective and inefficient management of school facilities by principals and school managers, and lack of commitment to providing efficient school infrastructure and management. As a result, teachers cannot fulfil their teaching responsibilities adequately and this has a negative effect on the quality of teaching and learning (Osunde & Omoruyi, 2005:416). Teachers often also work in unsafe and unhealthy conditions which lowers their morale (Ofoegbu, 2004:83; Osunde & Izevbigie, 2006). It is therefore important to acknowledge the need to motivate staff in order to produce desirable educational outputs (Ofoegbu, 2004; Osunde & Izevbigie, 2006).

Garuba (2004) points out that the participation of staff in refresher courses may motivate them to improve their performance. In such courses staff can reflect on their everyday problems, seek solutions to problems and report the findings at workshops, seminars or staff meetings.

There is currently a void in the literature on private schooling in Nigeria (Tooley, Dixon & Olaniyan, 2005:128) and no literature on the evaluation of PD programmes for Nigerian schools. This study therefore focuses on the impact of a PD programme conducted by academic staff at the University of South Africa (Unisa) for selected staff members from independent schools in Nigeria. The majority of independent schools are run by proprietors (Tooley et al., 2005:131), as was the case with the staff who participated in this study. Evaluating the success of a programme is considered to be a critical and integral part of any PD programme (Russell, 2001; Vincent & Ross, 2001).

Theoretical framework

Both adult learning theories and constructivist learning theories shed light on understanding adult development and growth in order to support the development of adults' knowledge and skills (Grado-Severson, 2007). Adults bring numerous life and work experiences, needs, personalities, and learning styles to their learning, which also shape their perspectives on learning, education and PD (Grado-Severson, 2007; Knowles, 1984). Theories of adult learning and development illuminate how adults can be supported when they engage in PD.

Knowles' (1984) theory of andragogy is an attempt to develop a theory specifically for adult learning. Knowles (1984) emphasises that adults are self-directed and expect to take responsibility for decisions. Andragogy makes the following assumptions about the design of learning: (1) Adults want to understand why they need to learn something; (2) experiential learning is recommended for adults; (3) adult learning is facilitated by challenging and relevant problem-solving; and (4) adults learn best when the topic is of immediate value. Hirsh (2005) and Lee (2005) state that the beliefs and assumptions about adult learning need to form the foundation of PD programmes.

Constructivist learning theory suggests that learning is a constructive process in which the learner builds an internal illustration of knowledge, a personalinterpretation of experience, a "sense-making process where the individual builds new knowledge and understanding from the base of existing knowledge and perceptions" (Chalmers & Keown, 2006:148). Constructivist approaches can be used to operationalised certain aspects of PD. In this regard the following is important (Chalmers & Keown, 2006; Wenger, 2007; Hodkinson & Hodkinson, 2007):

• The constructed meaning of knowledge and beliefs: In this process teachers acquire new knowledge, skills and approaches and then interpret their meaning and significance.

• The social and distributed nature of cognition: Teachers learn best when they work in a community characterised by action and dialogue. Conceptual growth comes from sharing perspectives. The simultaneous changing of internal representations as a response to those perspectives and collective experiences also does not take place in isolation.

• The situated nature of cognition: This element recognises the fact that PD needs to be closely linked to real-life situations and the particular contexts of individual schools.

• The importance of sufficient time for the above-mentioned aspects. New developments and effective change take time to be explored and to occur. Unfortunately short courses, while being worthwhile in other ways, do not allow time for the four elements of the constructivist approach.

The purpose of the study was to explore the perceptions of Nigerian delegates from independent schools of a training programme designed for their professional growth and to meet their professional needs.

Research design

Collaboration between staff in independent schools and academic staff in Education Management at Unisa started in 2007. The aim has been the PD of staff to improve teaching and learning in Nigerian independent schools. In February 2009, a delegation of proprietors from Nigerian independent schools visited Unisa and shared their concerns about their schools and suggested a PD programme to meet their needs. Team discussions between academic staff who were interested in this collaboration were initiated and the programme content of a workshop based on the needs expressed by proprietors and the expertise of facilitators was compiled and submitted for approval to the Director of Accelerated Learning Systems in Nigeria. With the assistance of the Centre for Community Training and Development, the first workshop on creating an effective learning environment for Nigerian independent schools was presented on in March, 2008. Owing to its success, the Director of Accelerated Learning Systems requested that it be repeated in October, 2008 for another group of school managers of independent schools. Both workshops covered topics involving self-management; creating a positive teaching and learning environment; instructional leadership: the key to a sound culture of teaching and learning; change management; improving a school through action research; managing a classroom within a human rights framework; and problem-solving skills in management. Seven workshop sessions were presented by seven academics in the field of education management at Unisa. They agreed to contextualise the session's content for the Nigerian school system and to actively involve all participants throughout their presentations. The findings were necessary to prepare future training workshops for staff from Nigerian independent schools.

A mixed-method approach (Bryman 2006; Miller & Gatta, 2006) was adopted to evaluate the perceptions of delegates in the two similar workshops during 2008. Feedback from the delegates who attended the workshops was therefore collected through quantitative (Phase 1) and qualitative research methods (Phase 2). Using a survey design by means of a constructed questionnaire in the first phase focusing on workshop 1 and open-ended questions for individual comments on their perceptions of workshop. A qualitative approach was used in Phase 2 where the perceptions of the second group of staff from independent schools were determined. During Phase 2 data were gathered by means of written reports on open-ended questions and a report-back session during the second workshop.

Phase 1

In Phase 1, 27 delegates attended the workshop. The researcher issued 27 copies of the questionnaire to them. The respondents were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of all the information to be supplied. The researcher used a questionnaire in the survey design as the research instrument to evaluate the perceptions of delegates. The questionnaire was improved by using input from seven members of the team presenting the workshop and the Director of Accelerated Learning Systems. This led to modification of some aspects of the questionnaire, adding to its content validity and face validity. The questionnaire consisted of four sections. Section A focused on demographic information of the respondents including their gender, years of experience, post level, previous training and the type of school at which they were teaching; Section B covered the quality of the presentation; Section C covered content and learning experience; and Section D covered general matters. The five-point Likert response rating scale in Sections B, C and D was adopted for the study. It ranged from very poor (1) to excellent (5). All sections included an open-ended question to comment on the particular issue. At the end of the questionnaire respondents indicated their general impression of the workshop and possible themes for future workshops.

Statistical processing was done with the aid of the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) statistical package, version 9.3. For the purposes of this study only means and standard deviations were calculated to determine the perceptions of participants.

Phase 2

The second group of delegates who attended the workshop in Phase 2 consisted of 33 participants who did not attend the first workshop. During this phase qualitative research methods were employed to gain an understanding of delegates' experiences of the workshop and to be better informed to support the PD of staff and Nigerian independent schools. The facilitator managing the evaluation session requested the delegates to form groups. They were asked to report in writing as well as orally on the following questions: the three major needs they had in their schools in Nigeria; what delegates had gained from the workshop; what they were going to apply in their educational situation after the workshop; and what topics they would like to see added to future workshops.

During the feedback session, groups reported on these questions and more unanticipated information was added to the written questions during the session. Written reports were collected and the researcher made field notes during the report-back session. All responses from open-ended questions in the questionnaire, as well as written reports and field notes during the feedback session, were organised and typed for the sake of analysing the data. A priori coding based on the content of the questionnaire and a written report from delegates were used in the analysis of data (Nieuwenhuis, 2010: 109).

Findings and discussion

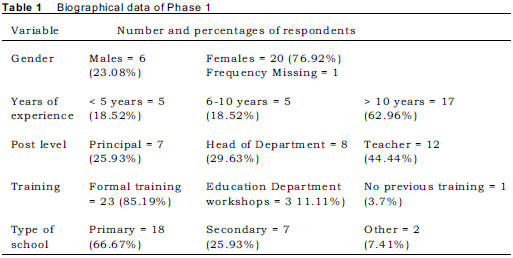

The results in Phase 1 covered the delegates' biographical data, their perceptions of the quality of the presentations and the content and the learning experience and the extent to which their expectations had been met. Table 1 sets out the biographical data of Phase 1.

Table 1 indicates that respondents in the first phase of the study consisted mainly of females (76.92%), most (62.96%) had more than 10 years' experience, 85.19% had formal training and 66.67% were stationed at primary schools, revealing a highly qualified and experienced group of respondents. The post levels of respondents revealed that seven were principals, eight were heads of departments and 12 were teachers. Since qualitative research does not require biographical data, such data were not collected during the second phase.

Perceptions of the professional development programme

The following section of the questionnaire (Phase 1) focused on the perceptions of the quality of the different presentations, the quality of the content and learning experience and the extent to which the workshop had met the delegates' expectations.

Perceptions of the quality of the presentations

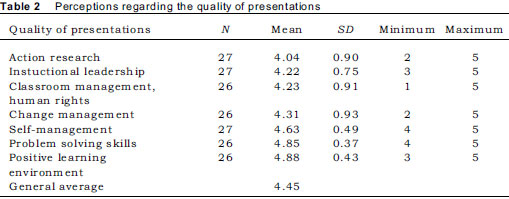

Table 2 indicates that the respondents rated the quality of the presentations generally as "good" with the average scores for all the individual items (aspects) rated a value of 4 or above. The average scores of quality varied from 4.04 to 4.88 with an overall average score of 4.45. The average score for the action research session was the lowest (4.04). Considering other crucial educational challenges in the Nigerian system, and that 18.52% of respondents had less than five years' experience, this score may indicate that action research may not be particularly relevant for their work situation since they had other more pressing issues to deal with. This may also explain why the presentation on the positive learning environment (4.88) and problem-solving skills (4.85) obtained the highest scores. In an informal discussion delegates indicated that the issue of human rights in classrooms is relatively new in Nigeria, which may explain why some indicated a "1" on the scale. However, since delegates were inexperienced, teachers need to be equipped with such knowledge and skills.

Although different delegates attended the workshops, the findings in the open-ended questions of Phase 1 and Phase 2 were consistent. Responses to the open-ended questions in Phase 1 revealed participants' appreciation of the knowledge and expertise of facilitators. In both the written comments of participants and the feedback session of Phase 2, participants expressed their gratitude for the "quality presentation of lecture materials in workbooks", the "conducive environment" (venue) in which the workshop was presented, the quality of presentations and the "cordial relationships with facilitators". It was clear that staff from independent schools seldom have the opportunity for PD presented by outside experts in another country, which may explain their appreciation for the quality and presentation of workshops.

Perceptions of the content and learning experience of the different sessions

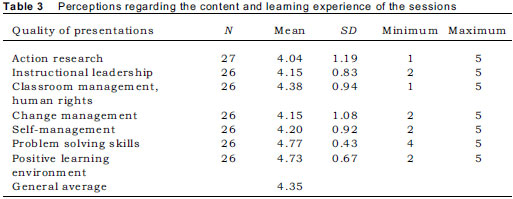

Table 3 presents the perceptions of delegates regarding the content and learning experience of the different sessions. It illustrates that respondents generally rated the content and learning experience related to the presentations as "good" with the average scores for all the individual items (aspects) rated at a value of 4 or above.

The average scores of content and learning experience varied from 4.04 to 4.77 with an overall average score of 4.35, which is considered between good and excellent. As in the case of participants' perceptions of the quality of the presentations in Table 1, the average score for perceptions of the content of the action research section was again the lowest (4.04) although still positive, while perceptions of the sections on positive learning environment (4.73) and on problem-solving skills (4.77) received the most positive review. Considering the current needs of staff in independent schools human rights and action research may not be such pressing issues in Nigeria which may explain the minimum score of "1" on the scale.

The results described above relate to some of the comments in the open-ended questions of Phase 1 and the written comments of Phase 2. Many of these comments were related to the content of certain sessions and how these sessions influenced their knowledge and skills. In this regard participants mentioned an improvement in self-management skills. As one group put it, "We got to know that we'll be very strong if we are able to manage ourselves well". Other groups felt that they had "learnt how to manage stress better than before" and that they could now cope with "everyday emotional stress". As regards the creation of a conducive environment for teaching and learning, delegates learnt the "importance of treating children with respect and placing value on them". They were now convinced that teachers needed to work with "empathy" and that they should "use humour to create a warm and friendly atmosphere where learners communicate freely with the teacher". This implies that "teachers should be emotionally inviting to children" and that "teaching is the work of the heart, which means that we need to have a passion for it". The workshop helped them to understand the importance of creating "a school where pupils appreciate learning and work in an atmosphere of love and friendship. This would enable them [pupils] to achieve their aims". In addition, participants believed that the workshop would assist them "to manage children in class" within a "human rights framework". Furthermore, participants learnt to manage their "own emotions, which would help [them] manage other people's emotions".

During the feedback session groups referred to the effect that managing change had. As one groups said, "We learnt that in all circumstances change must be communicated". Moreover, positive changes occur "when people understand changes. If they don't understand change, they see it as negative". They also learnt "to embrace change" to achieve teaching and learning aims and "to become effective change agents". The workshop reminded delegates to "meet the schools' objectives" and to "locate areas for improvement". It may also mean that they had to "sit back and take a break" in order "to look at areas to improve". It is interesting that one group felt that in "all school systems staff should take risks" and that schools should then actually "reward teachers who take risks".

Groups mentioned that they had benefitted a lot from the problem-solving session and that the workshop added to their knowledge of problem-solving. One group confirmed this succinctly: "We learnt to become effective problem-solvers". They also came to realise that for effective problem-solving to take place, it was necessary to get "a team to address challenges". In order to do this they needed to "listen and get information, analyse a problem, propose solutions, evaluate them and get parties involved" before a solution could be implemented. In dealing with problems, "we need to have a positive mind towards anything or any difficult situation at any time".

Perceptions regarding the expectations of the workshop

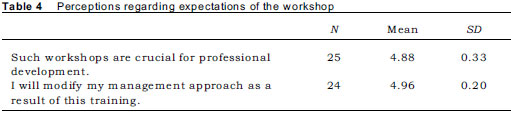

Table 4 indicates the perceptions as regards the expectations of the workshop. According to Table 4 respondents rated the item "Such workshops are crucial for my professional development" with an average score of 4.88 and the item "I will modify my management approach as a result of this training" with an average score of 4.96, both of which are very high and relate to "Excellent" (Table 4).

The quantitative results of Phase 1 are confirmed by the findings of Phase 2. In general, the qualitative data collected from participants in both phases reveal that they were very positive about the workshop and they thought that the gains were many. They reported the following: it "broadened the minds of management"; they were now "changed managers" and "more effective leaders". Participants mentioned that they had developed skills which enabled them to "go back and apply most of these things". It also helped them to consider making important changes in their teaching practice and "creating a better learning environment", and a "school climate that is friendly and inviting".

During the feedback session delegates in Phase 2 were requested to explain what and how they envisaged applying the knowledge and skills acquired during the workshop. As before, numerous ideas were mentioned. The following areas for improvement were identified: encouragement of colleagues to change, improvement of "teacher-pupil relationships", creation of a "warm and friendly atmosphere where children want to be", improvement of leadership and management in schools and problem-solving skills among teachers and pupils.

The way in which participants envisaged this would happen included "team work as a tool to development and change". One group referred to "creating a healthy team spirit both for pupils and teachers in ways to trust each other and themselves" in order to develop schools and to manage changes effectively. Another group suggested, "When we get back we'll organise an in-house workshop on how to manage emotions; how to create an effective classroom; how to manage changes. We'll make people know the reason for a particular change, giving them a clearer picture of what the change is all about. We will also make sure that we apply the three steps of problem-solving when problems arise". Yet another group referred to the importance of "being a good listener, seeking people's view" when focusing on development and improvement.

Successful PD is embedded in daily practice, is needs based and is linked to learner needs and tailored to meet the specific circumstances or contexts of teachers (What is Professional Learning, n.d.; Lee, 2005). As regards the content, the main focus should be on the acquisition of knowledge and skills and the improvement of teaching practice (Hodkinson, Colley & Malcolm, 2003:316). It is also important that teachers value the content and realise the possibility of integrating what they have learnt into their classroom practice (Hodkinson & Hodkinson, 2005:122). The findings support both adult learning and constructivist theories. Adults need to learn experientially, they approach learning as problem-solving and best learn when topics are of immediate value (Knowles, 1984). As regards constructive theories, delegates succeeded in acquiring new knowledge, skills and approaches and in interpreting their meaning and significance (Chalmers & Keown, 2006; Wenger, 2007; Hodkinson & Hodkinson, 2007).

PD workshops need to help staff plan for the application of the learning content once they are back in their own work environment (Smith & Gillespie, 2007). It is therefore important to make a strong connection between what is learned in the workshop and the staff members' own work contexts. This will assist them to apply the knowledge and skills they acquired during workshops more effectively. Moreover, they will be able to cascade the learning content within their individual schools by means of different PD programmes. As regards constructive theories delegates acknowledged that PD needs to be closely linked to the actual practices and the contexts of individual schools and it takes time for PD to be effectively implemented (Chalmers & Keown, 2006; Wenger, 2007; Hodkinson & Hodkinson, 2007).

Understanding the needs experienced in Nigerian schools

Needs assessment is an important first step to planning for quality workshops (Fratt, 2007:60). It means that the needs of participants should be determined, which will add to their active involvement in their own professional development (Fratt, 2007; Moswela, 2006). Apart from the initial visit by proprietors at which they indicated the needs of staff in Nigerian independent schools, the Unisa team was also interested in understanding the particular needs of delegates in Nigerian independent schools in both phases, with a view to planning for future workshops.

The findings from both phases revealed the following needs of staff from independent schools:

Consistently with the literature, delegates referred to the lack of funding which explains why schools could not provide quality teaching (Ogunyemi, 2005; Osunde & Omoruyi, 2005; Osunde &Izevbigie, 2006; Garuba, 2004). One group mentioned that 85% of public schools were not well-funded.

• Unqualified teachers lack the basics.

• Teachers have poor time-management skills.

• There is a lack of effective communication in schools and "teachers don't receive information".

• Many teachers lack commitment to the teaching profession as two delegates wrote: "Some become teachers but want to be doctors"; and "Teachers use teaching as stepping stone".

• Teachers experience a lot of stress in the teaching profession, in particular in coping with large classes.

• Teachers do not have exposure to global environments.

By considering the particular needs of delegates and their perceptions of the workshop this means that staff will be in a position to make recommendations for future workshops by indicating how they envisage such workshops should meet their professional needs.

Recommendations for future workshops

The groups in Phase 2 agreed on the future duration of workshops. They suggested more time for discussion during sessions and longer workshops. One group said, "The workshop should be at least a week long". The longer the PD, the more teachers can learn about their practice (Silins, Zarins & Mulford, 2002; Smith & Gillespie, 2007). This is also in line with the one aspect of the constructivist theory that suggests that new developments take time to be explored and effective change takes time to occur (Wenger, 2007). Since only a limited number of staff could attend the workshop, it was understandable that they suggested that all staff needed retraining. One group said, "We feel that teachers should be exposed to retraining so that they gain the way we gained". As said before, this recommendation is also in line with that of Garuba (2004) who recommends that Nigerian staff should be encouraged to participate in refresher courses.

One should keep in mind that factors such as financial constraints, time available, and the number of participants should always be considered in planning PD workshops. Although the ideal would be to train all staff on a specific topic, other methods such as cascading could be considered. Staff who attend workshops should be able on their return to schools to share the workshop with other staff members. This would enhance their own management skills and also provide an opportunity for empowering others in the school.

Participants referred to the importance of motivating staff and assisting staff in their commitment to teaching and learning for the sake of improved learner performance. With the low motivation and commitment levels among staff they believed that the necessary skills could enable them to address the problem more effectively. This need has also been identified in other Nigerian studies (Ofoegbu, 2004; Osunde & Izevbigie, 2006). As regards the need for motivating staff, the study by Ofoegbu (2004) confirms the assumption that teacher motivation could enhance school effectiveness and learner performance. Nigerian teachers work under unsafe and unhealthy conditions, which contribute to teachers' poor morale (Ofoegbu, 2004; Osunde & Izevbigie, 2006). It is therefore important to acknowledge the need to motivate staff in order to produce desirable educational outputs.

In general it can be stated that the workshops were rated positively. Respondents were in agreement with regard to whether their expectations had been met and whether the course content and learning experience had been beneficial. With regard to the various presentations, some presentations were rated significantly better than others, although they were still rated positively (generally "good" rather than "excellent").

Conclusion

PD is complex and poses difficulties for those planning and implementing PD programmes. This implies that PD should be customised and that it should recognise that different teachers will respond differently to the same circumstances. This is in agreement with the view of Hirsch (2005) who states that it is an important challenge to select appropriate PD in alignment with the assumptions and beliefs of teachers.

From both Phase 1 and Phase 2, it is clear that participants regarded the workshop as successful. The first phase provided an opportunity to evaluate the quality of different presentations, the quality of the workshop material in the workbook, whether their expectations had been met, what their views of the workshop were and what recommendations they could make for future workshop. Quality-wise, the presenters of the workshop and the content of learning material were highly rated. The workshop also succeeded in meeting delegates' expectations. Both Phase 1 and Phase 2 provided an opportunity for presenters to understand the needs in Nigerian schools, participants' experience of the workshop, participants' envisaged application of knowledge and skills in practice after attending the workshop and recommendations for future workshops. As a result of this study, the following suggestions of participants in both Phase 1 and Phase 2 assisted the team of presenters to identify the following topics for the workshop in October 2009: "Inspired through change"; "Manage yourself: be motivated"; "Teach from the heart"; "Invite to inspire through invitational education"; "Positive discipline: an instrument towards staff motivation and empowerment"; "Empower teachers through shared instructional leadership"; and "Motivate your staff: practical guidelines".

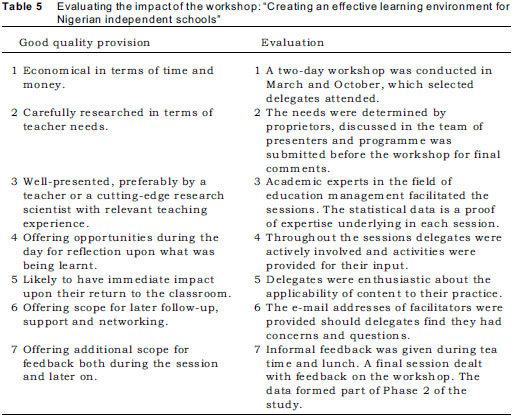

In summary, Table 5 indicates the characteristics of effective PD programmes as applied to the workshop for Nigerian staff.

The study concluded with a statement by Garuba (2004:202), "Teachers need to be helped out of poverty of knowledge and ruts through integrated programmes of enriched working environment, social recognition and, of course, continuing professional development".

References

Boyle B, Lamprianou I & Boyle T 2005. A longitudinal study of teacher change: What makes professional development effective? Report of the second year of the study. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 16:1-27. [ Links ]

Bryman A 2006. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qualitative Research, 6:97-113. [ Links ]

Chalmers L & Keown P 2006. Communities of practice and professional development. International Journal of Lifelong Learning, 25:139-156. [ Links ]

Desimone LM, Smith TM & Ueno K 2006. Are teachers who sustained, content-focused professional development getting it? An administrator's dilemma. Educational Administration Quarterly, 42:179-215. [ Links ]

Doring A 2002. Lifelong learning for teachers: Rhetoric or reality? Challenging futures? Changing agendas in teacher education. Armidale: New South Wales. Available at http://scs.une.edu.au/CF/Papers/pdf/ADoring.pdf. Accessed 17 August 2008. [ Links ]

Fratt L 2007. Professional development for the new century. District Administrator, 43:57-60. [ Links ]

Garuba A 2004. Continuing education: an essential tool for teacher empowerment in an era of universal basic education in Nigeria. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 23:191-203. [ Links ]

Geo-Jaja MA 2004. Decentralisation and privatisation of education in Africa: which option for Nigeria? International Review of Education, 50:307-323. [ Links ]

Grado-Severson E 2007. Helping teachers learn: principals as professional development leaders. Teachers College Record, 109:70-125. [ Links ]

Gray SL 2005. An enquiry into continuing professional development for teachers. University of Cambridge: Esmee Fairbairn Foundation. [ Links ]

Hodkinson H & Hodkinson P 2005. Improving schoolteachers' workplace learning. Research Papers in Education, 20:109-131. [ Links ]

Ikoya PO & Onoyase D 2008. Universal basic education in Nigeria: availability of schools' infrastructure for effective programme implementation. Educational Studies, 34:11-24. [ Links ]

Knowles M 1984. The adult learning: A neglected species. 3rd edn. Houston, TX: Gulf. [ Links ]

Lee HL 2005. Developing a professional development programme model based on teachers' needs. The Professional Educator, XXVII:39-49. [ Links ]

Lee Y-J & Roth W-M 2007. The individual/collective dialectic in the learning organization. The Learning Organization, 14:92-107. [ Links ]

Meiers M & Ingvarsin L 2005. Investigating the links between teacher professional development and student learning outcomes. Available at http://www.dest.gov.au/NR/rdonlyres/993A693A-3604-400F-AB81-57F70A8A83A6/8039/Vol1Rev_Final_26Sept05.pdf Accessed 21 August 2008. [ Links ]

Mezirow J 2000. Learning to think like an adult: core concepts of transformation theory. In J Mezirow & Associates (eds). Learning as transformation: critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Miller SI & Gatta JL 2006. The use of mixed methods models in the humans sciences: problems and prospects. Quality and Quantity, 40:565-610. [ Links ]

Moswela B 2006. Teacher professional development for the new school improvement: Botswana. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 25:625-632. [ Links ]

Ofoegbu FI 2004. Teacher motivation: a factor for classroom effectiveness and school improvement in Nigeria. College Student Journal, 38:81-88. [ Links ]

Ogunyemi B 2005. Mainstreaming sustainable development into African school curricula: issues for Nigeria. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 72:94-113. [ Links ]

Okoroma NS 2006. Educational policies and problems of implementation in Nigeria. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 46:243-263. [ Links ]

Olalekan AM 2004. Stress management strategies of secondary school teachers in Nigeria. Educational Research, 46:95-207. [ Links ]

Ololube NP 2008. Evaluation competencies of professional and non-professional teachers in Nigeria. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 34:44-51. [ Links ]

Osunde AU & Izevbigie TI 2006. An assessment of teachers' attitude towards teaching profession in midwestern Nigeria. Education, 126:462-467. [ Links ]

Osunde AU & Omoruyi FEO 2005. An assessment of the status of teachers and the teaching profession in Nigeria. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 45:411-420. [ Links ]

Retna KS 2007. The learning organisation: the school's journey towards critical and creative thinking. The Asia Pacific-Education Researcher, 16:127-142. [ Links ]

Russell P 2001. Professional development: making it effective. Teacher Learning Network, 8:3-7. [ Links ]

Silins H, Zarins S & Mulford B 2002. What characteristics and processes define a school as a learning organisation? Is this a useful concept to apply to schools? International Education Journal, 3:24-32. Available at http://www.leadspace.govt.nz/leadership/pdf/school-as-learning-organisation.pdf Accessed 17 August 2008. [ Links ]

Smith C & Gillespie M 2007. Research on professional development and teacher change: implications for Adult Basic Education. Available at http://www.ncsall.net/fileadmin/resources/ann_rev/smith-gillespie-07.pdf Accessed 21 August 2008. [ Links ]

Sparks D 2003. Skill building. Journal of Staff Development, 24:29. [ Links ]

Teachers for the 21st Century - making the difference 2008. Australian Government; Department of Education, Employment and Workplace relations. Retrieved 19 August 2008 from http://www.dest.gov.au/sectors/school_education/policy_initiatives_reviews/reviews/previous_reviews/teachers_for_the_21st_century . [ Links ]

Tooley J, Dixon P & Olaniyan O 2005. Private and public schooling in low-income areas of Lagos State, Nigeria: a census and comparative survey. International Journal of Educational Research, 43:125-146. [ Links ]

Van Eekelen IM, Vermunt JD & Boshuizen HPA 2006. Exploring teachers' will to learn. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22:408-423. [ Links ]

Van Nieuwenhuis J 2010. Analysing qualitative data. In Maree K (ed.). First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Van Veen K & Sleegers P 2006. How does it feel? Teachers' emotions in a context. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38:85-111. [ Links ]

Vemiæ J 2007. Employee training and development and the learning organization UDC331.363. iFacta Universitatis, Economics and Organization, 4:209-216. [ Links ]

Vincent A & Ross D 2001. Personalise training: determine learning styles, personality types and multiple intelligence online. The Learning Organisation, 8:36-43. [ Links ]

Wenger E 2007. Communities of practice. Third Annual National Qualifications Framework Colloqium, 5 June 2007. Velmore Conference Estate. [ Links ]

What is a learning organisation? n.d. Available at ftp://ntftp2.pearsoned-ema.com/samplechaps/ftph/027363254X.pdf. Accessed 19 August 2008. [ Links ]

Author

Trudie Steyn is Professor in the Department of Further Teacher Training at the University of South Africa.