Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.28 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2008

CONTENTS

Getting the picture and changing the picture: visual methodologies and educational research in South Africa

Claudia Mitchell

Claudia Mitchell is a James McGill Professor in the Faculty of Education at McGill University, Montreal, Canada and an Honorary Professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. She is a widely published author and her research focuses on visual and other participatory approaches to research, particularly in the areas of HIV and AIDS, gender violence, teacher identity, youth culture, and girlhood studies. E-mail: Claudia.mitchell@mcgill.ca

ABSTRACT

At the risk of seeming to make exaggerated claims for visual methodologies, what I set out to do is lay bare some of the key elements of working with the visual as a set of methodologies and practices. In particular, I address educational research in South Africa at a time when questions of the social responsibility of the academic researcher (including postgraduate students as new researchers, as well as experienced researchers expanding their repertoire of being and doing) are critical. In so doing I seek to ensure that the term "visual methodologies" is not simply reduced to one practice or to one set of tools, and, at the same time, to ensure that this set of methodologies and practices is appreciated within its full complexity. I focus on the doing, and, in particular, on the various approaches to doing through drawings, photo-voice, photo-elicitation, researcher as photographer, working with family photos, cinematic texts, video production, material culture, advertising campaigns as nine key areas within visual methodologies.

Keywords: educational research; social change; visual methodologies

A few years ago Ardra Cole and Maura McIntyre, researchers at the Ontario Institute of Studies in Education in Canada, embarked upon a long-term study of adult caregivers caring for their elderly parents who were suffering from Alzheimer's in their project Living and Dying with Dignity: the Alzheimer's Project. (See McIntrye & Cole, 1999). Their project focuses specifically on the fact that relatively little is known about the experiences of caregivers, particularly in relation to taking on the role of 'parent', and, critically, what kind of support they need to sustain themselves in their care of their parents a care that cuts across legal issues, health care, emotional care, and public education. In their work they conducted many single face-to-face interviews with the caregivers, along with interviews of support groups, social workers and physicians. They translated their findings into an exhibition first displayed in the foyer of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Headquarters in Toronto and, later, across Canada.

The exhibition included a number of installations, including Lifeline, which was made up of a gigantic clothes line spread from one wall to another. Hanging from it were undergarments, up to and including adult-sized diapers. As the description on the Centre for Arts Informed Research website expresses it:

A free standing clothes line about 20 feet in length is held up by ropes and secured by concrete blocks at each end. Astro turf carpeting represents the grass below; a chair invites the viewer to sit and relax. The clothes on the line are blowing in the breeze. The undergarments are ordered from left to right according to the time in the life cycle at which they are worn (http://www.utoronto.ca/CAIR/projects.html#alz).

Another part of the installation, Still life 1, includes a series of refrigerator doors, each with a different arrangement of fridge magnets holding a variety of artifacts: a school photo of a child (perhaps a grandchild), reminder notes about medication and so on. In another of their exhibitions set up in Halifax there is a voice activated tape recorder where viewers can sit and tell their own "caring for" stories. Another installation, Alzheimer's Still Life 2, contains a series of visual images taken from family photograph albums of the two artist-researchers, both of whom themselves are adultcare givers who looked after their respective mothers suffering from Alzheimer's. As their curatorial statement says, the particular photos "were chosen because they so clearly signify the mother-daughter connection over a life span and poignantly elucidate the role reversal that inevitably occurs when Alzheimer's interrupts, confuses, and redefines a relationship" (http://www.utoronto.ca/CAIR/ projects.html#alz).

Their work demonstrates some of the complexities related to what is actually meant by visual methodologies, showing, for example, the multiple forms of visual data including domestic photos taken from family albums and material culture (adult-sized diapers, fridge magnets). Their work also shows the multiple ways of working with the visual: both representation (transforming the interviews into visual representations, through the use of material culture), dissemination (creating a visual exhibition that drew the attention of the public, as well as that of health care researchers and health care policy makers), but also, as we see in the second level of interviews with the participants, a mode of inquiry (a type of data elicitation).

There are two other aspects of the visual that are also critical. One relates to epistemology and how it is that we come to know what we know (and how to account for subjectivity and validity). The two researchers are clearly inside their own experience as caregivers, as much as they are studying the experiences of the hundreds of other caregivers they have interviewed and met through their exhibitions. The other aspect relates to broader issues: Why engage in social science inquiry in the first place? and "What difference does this make anyway?"

For Cole and McIntyre, and for an increasing number of researchers engaged in social science research, the idea of how data collection can in, and of, itself serve as an intervention is crucial in that it can be transformative for the participants. Given the impact of these installations, people with a personal connection to the topic are "provoked" to tell their own stories. (Knowles & Cole, 2007) If visual data can mobilize individuals or communities to act, it may be possible to think of the idea of research as effecting social change.

At the risk of seeming to make exaggerated claims for visual methodologies, what I set out to do is lay bare some of the key elements of working with the visual as a set of methodologies and practices. In particular, I mean to address educational research in South Africa at a time when questions of the social responsibility of the academic researcher (including postgraduate students as new researchers, along with experienced researchers expanding their repertoire of being and doing) are critical. In so doing I seek to ensure that the term "visual methodologies" is not simply reduced to one practice or tool, and at the same time, to ensure that this set of methodologies and practices is appreciated within its full complexity.

Participatory and other visual approaches

Consider these prompts: "Draw a scientist;" "Take pictures of where you feel safe and not so safe;" "Produce a video documentary on an issue 'in your life';" "Find and work with seven or eight pictures from your family photographs that you can construct into a narrative about gender and identity". Each of these prompts speaks to the range of tools that might be used to engage participants (learners, teachers, parents, pre-service teachers) in visual research (a drawing, simple point-and-shoot cameras, video cameras, family photographs), and suggests some of the types of emerging data: the drawing, the photographic images and captions produced in the photo-voice project, the video texts produced in a community video project, and the newly created album or visual text produced by the participants in an album project.

In each case there is the immediate visual text (or primary text as John Fiske, 1989, terms it), the drawing, photo image, collage, photo-story, video documentary or narrative, or album, which can include captions and more extensive curatorial statements or interpretive writings that reflect what the participants have to say about the visual texts. In essence, their participation does not have to be limited to 'take a picture' or 'draw a picture', though the level of participation will rest on the time available, the age and ability of the participants and even their willingness to be involved. A set of drawings or photos produced in isolation of their full participatory context (or follow-up) does not mean that they should therefore be discarded, particularly in large-scale collections.

Each of these examples can also include what Fiske (1989) terms "production texts" or how participants engaged in the process describe the project, regardless of whether they are producing drawings, producing photographic images, video narratives, or 'reconstructing' a set of photographs into a new text, and indeed what they make of the texts. These production texts are often elicited during follow-up interviews. The production texts can also include secondary visual data based on the researcher taking pictures during the process and can show levels of engagement, something Pithouse and Mitchell (2007) in an article called 'Looking at looking" describe as a result of the visual representations of the engagement of children looking at their own photographs.

Each of the visual practices noted above and described in more detail later brings with it, of course, its own methods, traditions and procedures. This section maps out a range of approaches, from those that are relatively 'low tech' and can be easily carried out without a lot of expensive equipment, through to those which require more expensive cameras; from those that are camera-based to those that provide for a focus on things and objects (including archival photographs); from those where participants are respondents to those which engage participants as producers; from work where researcher and participants collaborate as well as those in which it is the researcher herself who is the producer and interpreter. The constant is some aspect of the visual.

Drawings

The use of drawings, for example, to study emotional and cognitive development, trauma and fears, and, more recently, issues of identity has a rich history. Using drawings in participatory research with children and young people along with groups, such as beginning teachers, is a well-established methodology. As a recent Population Council study points out, drawings offer children an opportunity to express themselves regardless of linguistic ability (Chong, Hallman & Brady, 2005). They also point out that work with drawings within visual methodologies is economical since all it requires is paper and a writing instrument. Drawings have been used with pre-service teachers in South Africa to study their metaphors on teaching mathematics in the context of HIV and AIDS (Van Laren, 2007); with children and pre-service teachers to study images of teachers (Weber & Mitchell, 1995; Mitchell & Weber, 1999); with children to study their perceptions of illness (Williams, 1998); children's perceptions of living on the street (Swart, 1988); violence in refugee situations (Clacherty, 2005), and on the perceptions of girls and young women in Rwanda on gender violence (Mitchell & Umurungi, 2007).

Photo-voice

Made popular by the award-winning documentary, Born into Brothels, photo-voice as Caroline Wang (1999) terms the use of simple point-and-shoot cameras in community photography projects has increasingly become a useful tool in educational research in South Africa. Building on Wang's work, which looks at women and health issues in rural China, Mary Brinton Lykes's (2001) work with women in post-conflict settings in Guatamela, Wendy Ewald's (2000) photography work with children in a variety of settings, including Nepal, the Appalachian region of the US and Soweto, and James Hubbard's (1994) work with children on reservations in the US, researchers in South Africa have worked with rural teachers and community health care workers to address numerous challenges and solutions when looking at HIV and AIDS (Mitchell, De Lange, Moletsane, Stuart & Buthelezi, 2005; De Lange, Mitchell & Stuart, 2007), These projects worked with teachers exploring gender (Taylor, De Lange, Dlamini, Nyawa & Sathiparsad, 1997) and poverty (Olivier, Wood & De Lange, 2007) and with learners in a variety of contexts, including exploring stigma and HIV and AIDS (Moletsane, De Lange, Mitchell, Stuart, Buthelezi & Taylor, 2007), rural learners (Karlsson, 2001), and safe and unsafe spaces in schools (Mitchell, Moletsane, Stuart, Buthelezi & De Lange, 2005); school toilets, Mitchell (in press). These are only some of the school-based research using photo-voice.

Photo-elicitation

Using photographs (either those generated through photo-voice or photo images brought to the interview either by the participants or the researcher) to elicit data offers educational researchers an entry point to the views, perspectives and experiences of participants. Collier and Collier (1986:105) suggest that "images invite[d] people to take the lead in inquiry, making full use of their expertise". They also suggest that using photographs in interviewing allows a full flow of interviewing to continue through second and third interviews, in ways in which merely verbal interviews do not.

Psychologically, the photographs on the table performed as a third party in the interview session. We were asking questions of the photographs and the informants [sic] became our assistants in discovering the answers to these questions in the realities of the photographs. We were exploring the photographs together (Collier & Collier, 1986:105).

While the range of topics and issues that might be addressed through photo-elicitation is vast, a particularly fascinating set of images within educational research can be found in work with 'the school photograph'. In previous work on school photography, Mitchell and Weber (1999) write about 'picture day' at school and the resulting portraits. Drawing on interviews with children and beginning teachers, they explore the conventions of this genre of photography: the 'sitting' often in front of a staged backdrop, such as a rainbow, forest, or landmark forces poses where the child may be required to hold a pen or a book or some other school-related artefact, and the subject often required (by the parents) to dress up. Subjects are usually required to smile, regardless of how they are feeling. What is present is what a consuming parent will want to purchase: a package of school photographs. What is absent is what the child really feels about the moment and perhaps some sense of the child's autonomy. Years later, as is evident in the interviews, subjects still look back on some of these sittings with dismay. Added to this dismay is the fact that their photos are sometimes still being displayed years later on the wall, mantle or television set of an aunt or grandparent. To take up Gillian Rose's (2001) point about whether photographs are stored and displayed, these 'lasting impression' images are usually out of the control of the child.

Family photographs

Clearly much has been done already on family albums, particularly in the area of the visual arts and art history. These studies range from work on one's own family album(s) (Kuhn, 1995; Mitchell & Weber, 1999; Spence, 1988; Spence & Holland, 1991; Weiser, 1993), to the work of Arbus (see Lee & Pultz, 2004), Chalfen (1991), Hirsch (1997), Langford (2001), and Willis (1994), to name only some of the scholars who examine 'other people's albums'. These various album projects have highlighted the personal aspect in looking at, or working with, one's own photographs, but there is also, as in the case of Langford, the idea of explicitly looking at 'other people's photo albums' through a socio-cultural lens. The issues that they have explored range from questions of cultural identity and memory, through to what Spence (1988) has described as 'reconfiguring' the family album. Faber's (2003) work on family albums in South Africa points to the rich possibilities for this work in exploring apartheid and post-apartheid realities. Mitchell and Allnutt (2007) and Allnutt, Mitchell, and Stuart (2007) have applied this work on family albums to participatory work with teachers in Canada and South Africa.

In one of the albums produced in an Honours module with teachers in South Africa, a young male teacher, T. (also documented in a video Our Photos, Our Videos, Our Stories, Mak, Mitchell & Stuart, 2005), uses the album project to explore one of the stark realities of life in rural KwaZulu- Natal in the age of AIDS death and dying, silences and 'the after life' (as in how the survivors deal with all of this). In this case, he documents the story of his sister who, in her early 20s, dies unexpectedly and mysteriously, leaving behind her six-year-old son to be raised by T. and the grandmother. T. uses the project to explore the silences, not just about the cause of his sister's death, and the importance of naming the disease, but also the position of AIDS orphans in this case, his young nephew. In T.'s 'performance' of the album, when he presents it to the class, he offers the image of his mother falling asleep with the album under her arm. It is a poignant representation of what the album project means to his family in terms of breaking silences.

Also described in Mitchell and Allnutt (2007), is Grace, a black teacher in her late 20s who, as the daughter of a domestic worker, is more-or-less adopted into the white family for whom her mother works. As Grace goes back through the family photos, she looks at the ways in which she is dressed the same as the little white girl in the family and the fact that they are sometimes given identical toys. The culminating event, ostensibly, is her graduation photo or is it? Grace's documentary is an interrogation of privilege her own to a certain extent, but this is not done unquestioningly.

There is Bongani, whose photographs of his daughter (born in 1994), are organized around the theme of the "decade of democracy" babies, as they have come to be called. His photo documentary takes us up to 2004, and like Grace's album, is not without questions about a post apartheid South Africa. Is it better? How have the hopes of April 1994 for a new beginning been fulfilled? And which ones have not?

Researcher as photographer/visual ethnographer

A less participatory though no less rich area of visual research using photographs, is the work of researchers themselves as visual ethnographers and visual artists, as we see in Douglas Harper's 15-year study of a dairy farming community in Changing work: Visions of a lost agriculture (Harper, 2001). We might also consider the photo work of Gideon Mendel (2001) on HIV and AIDS in southern Africa or the work of Marejka du Toit and Jenny Gordon (2007) who produced what they refer to as environmental portraits. In this photo work as part of the South Durban project where they have been looking at the effects of the oil refineries on the people living in the area, they have amassed a collection of photos of smoke stacks belching out pollutants, chained fences, landscape photos that position the residential area against the backdrop of the refineries and so on. The photos are devoid of people, though the impact of person-created pollution is everywhere.

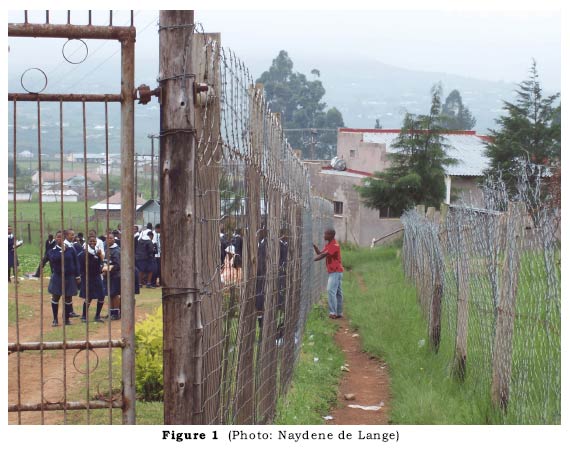

In the project, the photography of Du Toit and Gordon (2007) sits alongside both the photos produced by the participants who live in the area, as well as their family photographs which, as part of photo-elicitation, may talk to their lives "before pollution" (ranging from images of when they may have felt healthier or when a loved one was still alive). In other studies, as in the case of the research team photographing participants engaged in taking photographs (Pithouse & Mitchell, 2007), the process photos become visual data in and of themselves. The significance of the "photographic participant-observer eye" is highlighted, particularly within school-based research. De Lange, Mitchell and Bhana (2008), for example, include an image taken by a member of the research team as they were driving away from a school they were visiting (Figure 1). The image of the fence dividing the school girls on one side (and apparently in the safety of the school) and a young man on the other side, speaks to the ways in which schools remain sites of violence, and becomes part of a collection of photos over time from the view of the researchers. Such photographs serve as visual data (different from the types of images produced within a photo-voice or video project), and can themselves become part of an exhibition of visual representations, not unlike the collection of photos and writing found in texts such as Broken bodies, broken dreams (UNCHA, 2006).

Video

The use of video in educational research (beyond the use of video-taping classrooms and other settings or video-taping interviews) may be framed as collaborative video, participatory video, indigenous video, or community video. Sarah Pink (2001) argues that video within ethnographic research can break down traditional hierarchies between visual and textual data. She maintains that these hierarchies are irrelevant to a reflexive approach to research that acknowledges the details, subjectivities, and power dynamics at play in any ethnographic project. What runs across this work is the idea of participants engaged in producing their own videos across a variety of genres, ranging from video documentaries, video narratives (melodramas or other stories) or public service narratives. As with the work with photo-voice, both the processes and the products lend themselves to data analysis within visual studies.

In terms of process and video-making in southern African schools, Mitchell, Walsh and Weber (2007), Mitchell and Weber (2007), Moletsane, Mitchell, De Lange, Stuart and Buthelezi (in press), and Mitchell and De Lange (in press) write about the ways in which young people might participate in this work, noting the particular relevance of this work to addressing gender violence, and HIV and AIDS. Equally, though, the work with adults, teachers, parents and community health care workers is also critical, as can be seen in the work of Olivier, Wood and De Lange (2007) on poverty, and Moletsane, Mitchell, De Lange, Stuart. and Buthelezi (in press). Building on the work of Jay Ruby (2000) and others in relation to the idea of the ethnographic video as text, Mitchell and De Lange (in press), have reflected on what might be described as a meta-narrative on working with community based video through the researcher-generated production of a composite video of each project. The production of these composite videos is an interpretive part of the process (in relation to the research team). These composite videos become tools of dissemination but also, like the Cole and McIntyre project, serve to become new tools of inquiry when community participants view them.

Working with cinematic texts

Beyond the use of community video, educational researchers can also use commercial film narratives and documentaries within visual research. This work can include close readings of school or education-related texts in the vast array of teacher films, as Mitchell and Weber (1999), and Weber and Mitchell (1995) highlight in their analysis of teacher identities in such films as Kindergarten Cop, To Sir with Love, and Dangerous Minds. Several films are particularly relevant to studying education in South Africa: Sarafina in exploring education under apartheid education (Butler, 2000) and Yesterday in looking at such themes as rurality and HIV and AIDS.

Alongside the use of textual analysis to read social practices, researchers might also use film texts in more participatory work with audiences. As an intervention involving boys and the study of gender violence in South Asia, Seshradi and Chandran (2006) use various documentaries that address masculinities and such themes as friendship, violence and bullying to provoke reflection and discussion within focus groups. Using both pre-screening and post-screening, they were interested in how boys' attitudes changed as a result of the viewings and discussions. In studies on HIV and AIDS and sex education in South Africa, Mitchell (2006) and Buthelezi, Mitchell, Moletsane, De Lange, Taylor and Stuart (2007) refer to the use of the video documentary Fire+Hope to provoke discussion amongst young people in relation to addressing youth activism.

Material culture

How objects, things and spaces can be used within visual research in education draws on work in socio-semiotics, art history, consumer research. As noted at the beginning of this article in relation to the work of Cole and McIntyre, objects (including fridge magnets and adult-sized diapers) have connotative or personal meanings (and stories), which draw on autobiography and memory, along with their denotative histories, which may be more social and factual. Stephen Riggins' (1994) critical essay on studying his parents' living room offers a systematic approach to engaging in a denotative and connotative reading of the objects and things in one physical space. This work can be applied to a variety of texts, ranging from clothing and identity, bedrooms, documents and letters, and even desks and bulletin boards as material culture.

As Mitchell, De Lange, Moletsane, Stuart and Buthlelzi (2005) highlight, some of the 'photo subjects' mentioned in the interviews within a photo-voice project with teachers and community health care workers on HIV and AIDS are actually objects: a school bus, empty chairs and hair dryers in a beauty salon, or a shrivelled tree. Weber and Mitchell (2004a), in the edited book Not Just any Dress: narratives of memory, body and identity, offer a series of essays on the connotative meanings of various items of clothing. The collection of dress stories divided into "growing up with dresses", "dress and schooling', "dress rituals and mothers" "of dresses and weddings", "dressing identity", "bodies", and "dress and mortality" offers a reading on a wide range of issues of identity (mostly women's) across the life-span.

One of the chapters in the book, Liz Ralfe's (2004) narrative on the 'isishweshwe' focuses specifically on ethnic dress in South Africa. She interrogates the ways in which a type of fabric first associated with Dutch traders and later with Zulu women has now become 'common currency' for fashion more generally. And yet at the same time, this fabric still carries with it remnants as a signifier of a border-crossing identity, something Ralfe now takes up as a white woman (Ralfe, 2004). In her chapter she talks about what it meant to show up the first time at her workplace in a faculty of education in a skirt made of this fabric, noting in particular the reactions of black staff members. In a related way Edwina Grossi's (2007) auto-ethnographic work on her life as an early child educator in Durban shows the ways in which life-documents as material culture circulars, report cards, letters and photographs can serve as the raw material for engaging in self-study (see also Weber & Mitchell, 2004b).

Working with visual images within popular culture

The work on semiotics and visual images, particularly in advertising campaigns and public service announcements, draws on many of the techniques used in studying material culture, as well as some of the issues relating to working with a single photograph (Frith, 1997). This is a promising area within educational research in South Africa, applied, for example, to the work around HIV and AIDS, and in relation to gender violence in schools. The area includes the work of Johnny and Mitchell (2006) on deconstructing UNESCO's 'Live and Let Live', Stuart's (2004) analysis of media posters produced by pre-service teachers in Life Skills, and the work of Mitchell and Smith (2001) on the ABC campaign in schools.

"Help! What do I do with the visual images?" Interpretive processes and visual research

There is no quick and easy way to map out the interpretive processes involved in working with visual research any more than there is a quick and easy way to map out the interpretive processes for working with any type of research data, though Jon Prosser (1998), Marcus Banks (2001), Gillian Rose (2001) and Sarah Pink (2001), amongst other researchers working in the area, offer useful suggestions and guidelines. Some considerations include the following.

1. At the heart of visual work is its facilitation of reflexivity in the research process, as theorists on seeing and looking, such as John Berger (1982) and Susan Sontag (1977), have so eloquently discussed. Indeed, as Denzin (2003), and others have noted, situating one's self in the research texts is critical to engaging in the interpretive process.

2. Close reading strategies (drawn from literary studies, film studies and socio-semiotics, for example) are particularly appropriate to working with visual images. These strategies can be applied to working with a single photograph (see Moletsane & Mitchell, 2007), a video documentary text (see Mitchell, De Lange, Moletsane, Stuart, Taylor & Buthelezi, in press; Weber & Mitchell, 2007), or a cinematic text (Mitchell & Weber, 1999).

3. Visual images are particularly appropriate to drawing in the participants themselves as central to the interpretive process. In work with photo- voice, for example, participants can be engaged in working with their own analytic procedures with the photos: which ones are the most compelling? How are your photos the same or different from others in your group? What narrative do your photos evoke? (see De Lange Mitchell, Moletsane, Stuart & Buthelezi, 2006). Similarly with video documentaries produced as part of community video, participants can be engaged in a reflective process, which also becomes an analytic process: What did you like best about the video? What would you change if you could? Who should see this video? The interpretive process does not have to be limited to the participants and the researcher. Communities themselves may also decide what a text means. Because visual texts are very accessible, the possibilities in inviting other interpretations are critical to this issue (see, for example, Mitchell, 2006).

4. The process of interpreting visual data can benefit from drawing on new technologies. Transana, for example, is a software application that is particularly appropriate to working with video data (Cohen, 2007). The use of digitizing and creating meta-data schemes can be applied to working with photo-voice data (see, for example, Park, Mitchell & De Lange, 2007).

5. The process of working with the data can draw on a range of practices that may be applied to other types of transcripts and data sets, including content analysis, and engaging in coding and developing thematic categories.

6. Archival photos (both public and private) bring their own materiality with them and may be read as objects or things. Where are they stored? Who looks after them? (see also Rose, 2001; Edwards & Hart, 2004).

7. Visual data (especially photos produced by participants), because it is so accessible, is often subjected to more rigorous scrutiny by ethics boards than most other data. As the section above highlights, there are many different ways of working with the visual and the choice of which type of visual approach should be guided by, among other things, the research questions, the feasibility of the study, the experience of the researcher, and the acceptability to the community under study.

8. Working with the visual to create artistic texts (for example, installations, photo albums, photo exhibitions, video narratives), as we saw in the case of Cole and McIntyre noted above, should be regarded as an interpretive process in itself. This point is a critical one in understanding the relationship between visual studies and arts-based research (Knowles & Cole, 2007; Bagley & Cancienne, 2002; Denzin, 1997; Eisner, 1995; Barone, 2001).

On the limitations and challenges

Lister and Wells (2001) stress the unprecedented importance of imaging and visual technologies in contemporary society and they urge researchers to take account of those images in conducting their investigations. Over the last three decades, an increasing number of qualitative researchers have indeed taken up and refined visual approaches to enhance their understanding of the human condition. These uses encompass a wide range of visual forms, including films, video, photographs, drawings, cartoons, graffiti, maps, diagrams, cyber graphics, signs, and symbols.

Although many of these scholars normally work in visual sociology and anthropology, cultural studies, and film and photography, a growing body of interdisciplinary scholarship is incorporating certain image-based techniques into its research methodology. Research designs which use the visual raise many new questions and suggest new blurrings of boundaries: Is it research or is it art? Is it truth? Does the camera lie? Is it just a 'quick fix' on doing research? How do you overcome the subjective stance? The emergence of visual and arts-based research as a viable approach is putting pressure on the traditional structures and expectations of the academy. Space, time, and equipment requirements, for example, often make it difficult for researchers to present their work in the conventional venues and formats of research conferences.

Yet, there are other questions which interrogate even more the relationship between the researched and the researcher. Do we as researchers conduct ourselves differently when the participants of our studies are 'right there', either in relation to the photos or videos they have produced, or in their performance pieces? How can visual interventions be used to educate community groups and point to ways to empower and reform institutional practices? What ethical issues come to the fore in these action-oriented studies? How do we work with such concepts as 'confidentiality' and 'anonymity' within this kind of work, for example, in research where stigma itself is a major issue?

Emmison and Smith (2000) state that one of the issues in visual research is the "methodological adequacy" of the method, but we must challenge the adequacy of the questionnaire, the interview, and the photograph/drawing/ video. That does not mean that we exclude the visual, but that we examine its function, use and limitations, and continue with the process, taking all these aspects into account. They are equally concerned with the partiality of the photograph: a photograph "must always be considered a selective account of reality" (Emmison & Smith, 2000:40). As Goldstein (2007:61) writes, "All photos lie". At the same time, there remains the emotional impact of the image, which can even overwhelm the researcher and the viewer and can even preclude a proper analysis of content. This element cannot be ignored when we consider the power of the photograph or other visual image.

Clearly some studies lend themselves to one type of visual data more than another (archival photos over video production, for example), and not all questions are best answered through the use of the visual. If there are few research questions that could not be addressed through visual methodologies, this does not mean that this is the only approach, or that all audiences or recipients of research (funders, policy makers, review boards) are equally open to qualitative research, generally, or visual research, specifically. And as Karlsson (2007) points out, the time and effort that this takes, particularly for Honours and Masters students, may be a major challenge. At the same time, the preparation of new researchers in this area, postgraduate students for example, relies on access to methodology textbooks and other course material that offers them full support for making informed choices about methods.

It is incumbent on those who are teaching courses in research methodologies, especially in Education, to ensure that students are exposed to a variety of approaches, and even if the students do not choose to work with the visual, they should be able to evaluate critically those studies that draw on visual methodologies in the same way that they can evaluate critically a variety of approaches including interview studies, case studies, statistical studies and so on. Concomitantly, it is critical that those of us whose research is grounded in visual methodologies ensure that we contribute to broader debates within and beyond our institutions about the kind of support that is needed along with attention to critiques. Significantly, we need to provide training to our research students working on funded projects, and, where possible, bring forward our expertise in working with the visual to review boards, research committees and so on. Technically, we need to be cognisant of some of the limitations of working with large electronic files, and become attuned to new ways of working with digitizing and other techniques that are critical to the success of working with the visual (Park, Mitchell & De Lange, 2007).

... And finally, what about reaching the public?

"Why are there no white people in the film?"

"Why did you choose this talking head genre? Wouldn't it be more effective to create a story line or a drama?"

"Where did you get the statistics about boys being at risk? Are those numbers true?"

"Could you help us do research?"

"Why can't we produce something like this right here in KwaZulu-Natal where the problems are even greater than in the Western Cape?"

These questions may sound like the kind of questions that would be raised by an external reviewer of a journal article or research proposal, or, at the very least, a film critic. They were questions posed to me at a Youth Day event in Marianhill near Pinetown in 2004 by members of the audience, young people from the area who had just viewed the video documentary Fire+Hope of the group from the Western Cape. In actual fact, as I stood on the stage and attempted to answer their questions, I think I would have preferred to have faced a reviewer or a film critic.

They are tough questions. Why are there no white people in the film? There are no white people in the film, because there were no white people in the Soft Cover project that we carried out in Khayelitsha and Atlantis in the Western Cape. Or, I could say that there ended up being no white people in the project, though there was one young man at the beginning who dropped out, and probably did so for a variety of reasons. It was an after-school project focusing on youth activism and HIV and AIDS. He tells us that he is too busy with the organized after-school events at this school. But perhaps another version of the story is that he isn't allowed to travel to Atlantis or Khayeletisha, our other two sites. And the funding is not large enough to transport every participant out of Khayelitsha or Atlantis and for just one person. We aren't quite sure. But I wished I had had a better answer, and I wished that the audience didn't have to ask the question in the first place (see also Walsh & Mitchell, 2004).

As has been noted by Burt and Code (1995), Schratz and Walker (1995), Gitlin (1994), and Smith (1999), the issue of research accessibility is a critical topic within institutional practices. It becomes especially so when the topics of the research are as vital a part of the social situation in South Africa as education and health care, and where issues of power, control, regulation, and access are ones that are central to policy development. Notwithstanding my inability to provide appropriate answers, what this event highlights is the 'migration' of the views of one group of young people (from the Western Cape) as represented in Fire+Hope to another group of young people in KwaZulu- Natal.

What this event also highlights is the dissemination of research findings (about youth activism and HIV and AIDS, and involving youth activists) to a group of young people who are attending a community programme on youth and HIV and AIDS on Youth Day. What starts as research (a project interrogating youth activism and HIV and AIDS) and becomes a visual text (a 16- minute video documentary Fire+Hope) evolves into becoming an intervention (a screening and discussion at a Youth Day event) and then yields more research questions, both for the research team and the audience (who in turn also want to make their own video documentary). The example of the transfer of knowledge and engagement from a group of young people in the Western Cape to a group of young people in KwaZulu-Natal through the medium of a video documentary produced within a visual studies project highlights a type of peer education and social networking that, while pre-dating Facebook and My Space, is no less striking for what it can inspire.

Conclusion

Though the description of visual methodologies here may seem both ridiculously simple and ridiculously complex, clearly this paradox can resolve itself in the doing of the research, something that is evident in the work of Cole and McIntyre, cited at the beginning of this article, but also something that is evident in the example above of the youth viewers of Fire+Hope. In the article I have focused on the doing, and in particular the various approaches to doing through the visual (drawings, photo-voice, photo-elicitation, researcher as photographer/visual ethnographer, working with family photos, cinematic texts, video production, material culture, advertising campaigns).

There are, of course, a number of other visual approaches, including archival work, collage, and performance. While the article also offers some comments on the interpretive process, the types of issues that might be addressed, some limitations to visual research, and finally some notion of the ways in which the visual can serve recursively as a mode of inquiry, as a mode of representation and as a mode of dissemination, it is far from being a comprehensive 'primer' on visual methodologies. It suggests, rather, that visual studies have a great deal to offer educational research in South Africa.

Acknowledgements

Much of the work for this article came out of my work with the research teams at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, working out of the Centre for Visual Methodologies for Social Change (www.cvm.org), Naydene De Lange, Jean Stuart, Relebohile Moletsane, Thabisile Buthelizi and Myra Taylor. I also acknowledge the contributions of Susann Allnutt, Shannon Walsh and Sandra Weber to this project. I thank Ann Smith and Katie MacEntee for their assistance with manuscript preparation.

References

Allnutt S, Mitchell C & Stuart J 2007. The visual family archive: Uses and interruptions. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart (eds). Putting people in the picture. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Alzheimers Still life 1. Available at http://www.utoronto.ca/ CAIR/projects.html#alz. Accessed April 29 2008. [ Links ]

Alzheimers Still life 2. Available at http://www.utoronto.ca/ CAIR/projects.html#alz. Accessed April 29 2008. [ Links ]

Bagley C & Cancienne MB (eds) 2002. Dancing the data. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Banks M 2001. Visual methods in social research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Barone T 2001. Science, art, and the predisposition of educational researchers. Educational Researcher, 30:24-29. [ Links ]

Berger J 1982. Ways of seeing. London: BBC/Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Burt S & Code L (eds) 1995. Changing methods: Feminists transforming practice. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press. [ Links ]

Buthelezi T, Mitchell C, Moletsane R, De Lange N, Taylor M & Stuart J 2007. Youth voices about sex and AIDS: Implications for life skills education through the "Learning Together" project in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11:445-459. [ Links ]

Butler F 2000. A Hollywood curriculum in a Bahamian teacher education program. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, McGill University. [ Links ]

Chalfen R 1991. Turning leaves: Exploring identity in Japanese American photograph albums. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. [ Links ]

Chong E, Hallman K & Brady M 2005. Generating the evidence base for HIV/AIDS policies and programs. New York: Population Council. [ Links ]

Clacherty G 2005. Refugee and returnee children in Southern Africa: Perceptions and experiences of children. Pretoria: UNHCR. [ Links ]

Cohen L 2007 Transana: Qualitative analysis for audio and visual data. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart (eds). Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Collier J & Collier M (eds) 1986. Visual anthropology: Photography as a research method. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [ Links ]

De Lange N, Mitchell C & Bhana D 2008. 'If we can all work together' in the age of AIDS. Poster presentation American Education Research Association, New York, 24-27 March. [ Links ]

De Lange N, Mitchell C, Moletsane R, Stuart J & Buthelezi T 2006. Seeing through the body: Educators' representations of HIV and AIDS. Journal of Education, 38:45-66. [ Links ]

De Lange N, Mitchell C & Stuart J (eds) 2007. Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Denzin NK 1997. Performance texts. In: WG Tierney & YS Lincoln (eds). Representation and the Text:Re-framing the Narrative Voice. Albany NY: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Denzin NK 2003. The cinematic society and the reflexive interview. In: J Gubrium & J Holstein (eds). Postmodern interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Du Toit M & Gordon J 2007 The means to turn the key: The South Durban Photography Project's workshops for first time photographers, 2002-2005. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart (eds). Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Edwards E & Hart J (eds) 2004. Photographs, objects, histories on the materiality of images. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Eisner EW 1995. What artistically crafted research can help us understand about schools. Educational Theory, 45:1-6. [ Links ]

Emmison M & Smith P 2000. Researching the visual: images, objects, contexts and interactions in social and cultural inquiry. London: Sage [ Links ]

Ewald W 2000. Secret games: Collaborative works with children, 1969-99. Berlin and New York: Scalo. [ Links ]

Faber P (compiler) 2003. Group portrait South Africa: Nine family histories. Capetown, SA: Kwela Books. [ Links ]

Fiske J 1989. Understanding popular culture. Boston, MA: Unwin. [ Links ]

Frith KT 1997. Undressing the ad: Reading culture in advertising. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Gitlin A 1994. Power and method: Political activism and educational research. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Goldstein B 2007. All photos lie. Images as data. In: GS Stanczak (ed.). Visual research methods: Image, society and representation. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Grossi E 2007. The 'I" through the eye: Using the visual in arts-based autoethnography. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart (eds). Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Harper D 2001. Changing work: Visions of a lost agriculture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Hirsch M 1997. Family frames: Photography, narrative and postmemory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Hubbard J 1994. Shooting back from the reservation. New York: New Press. [ Links ]

Johnny L & Mitchell C 2006. "Live and let live" An analysis of HIV/AIDS related stigma and discrimination in international campaign posters. Journal of Health Communication, 11:755-767. [ Links ]

Karlsson J 2007. The novice researcher. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart (eds). Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Karlsson J 2001. Doing visual research with school learners in South Africa. Visual Sociology, 16:23-37. [ Links ]

Knowles G & Cole A (eds) 2007. Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples and issues. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Kun Yi W, Cheng Li V, Wen Tao Z, Ke Lin Y, Burris M, Yi Ming W, Yan Yun X & Wang C (eds) 1995. Visual voices. 100 photographs of village China by the women of Yunnan Province. Yunnan: Yunnan People's Publishing House. [ Links ]

Kuhn A 1995. Family secrets: Acts of memory and imagination. London and New York: Verso. [ Links ]

Langford M 2000. Suspended conversations: The afterlife of memory in photographic albums. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press. [ Links ]

Lee A & Pultz J 2004. Diane Arbus: Family albums. Yale University Press. [ Links ]

LifeLine. Available at http://www.utoronto.ca/CAIR/projects.html#alz. Accessed April 29 2008. [ Links ]

Lister M & Wells L 2001. Seeing beyond belief: Cultural studies as an approach to analysing the visual. In: T van Leeuwen and C Jewitt (eds). Handbook of visual analysis. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Lykes MB 2001. Creative arts and photography in participatory action research in Guatemala. In: P Reason & H Bradbury (eds). Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Mak M, Mitchell C & Stuart J 2005. Our photos, our videos, our stories. Documentary produced by Taffeta Production, Montreal, Canada. [ Links ]

McIntyre M & Cole AL 1999. Still life with Alzheimer's. From (first installation) In illness and in health: Daughters storying mothers' lives (1st installation) [multi-media exhibit: ]. Presented at the Third Annual International Conference on Mothers and Education, Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario. [ Links ]

Mendel G 2001. A broken landscape: HIV/AIDS in Africa. London: Network Photographers. [ Links ]

Mitchell C 2006. Visual arts-based methodologies in research as social change. In: T Marcus & A Hofmaenner (eds). Shifting the boundaries of knowledge. Pietermartizburg: UKZN Press [ Links ]

Mitchell C & Allnutt S 2007. Working with photographs as objects and things: Social documentary as a new materialism. In: G Knowles & A Cole (eds). Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples and issues. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Mitchell C & De Lange N (in press). "If we hide it … it doesn't exist when it actually does". Community video in the age of AIDS. In: L Pauwels (ed.). Handbook on visual research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, De Lange N, Stuart J, Moletsane R & Buthelezi T 2007. Children's provocative images of stigma, vulnerability and violence in the age of AIDS: Revisualizations of childhood. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart (eds). Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, De Lange N, Moletsane R, Stuart J, Taylor M & Buthelezi T (in press). "Trust no one at school": Participatory video with young people in addressing gender violence in and around South African schools. In: F Ogunleye (ed.). African Video Film Today 2. Matsapha, Swaziland: Academic Publishers Swaziland. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, De Lange N, Moletsane R, Stuart J & Buthelezi T 2005. The face of HIV and AIDS in rural South Africa : A case for photo-voice. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3:257-270. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, Moletsane R, Stuart J, Buthelezi T & De Lange N 2005. Taking pictures/taking action! Using photo-voice techniques with children. ChildrenFIRST 9, 60:27-31. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, Moletsane R & Stuart J 2006. Why we don't go to school on Fridays: Youth participation and HIV and AIDS. McGill Journal of Education, 41:267-282. [ Links ]

Mitchell C & Smith A 2001. Changing the picture: Youth, gender and HIV/AIDS prevention campaigns in South Africa. Canadian Woman Studies/les cahiers de la femme,1:56-62. [ Links ]

Mitchell C & Umurungi JP 2007. What happens to girls who are raped in Rwanda. Children First, 13-18. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, Walsh S & Weber S 2007. Behind the lens: Reflexivity and video documentary. In: G Knowles & A Cole. The art of visual inquiry. Halifax: Backalong Press. [ Links ]

Mitchell C & Weber S 1999. Reinventing ourselves as teachers: Beyond nostalgia. London: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Moletsane R & Mitchell C 2007. On working with a single photograph. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart (eds). Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Moletsane R, De Lange N, Mitchell C, Stuart J, Buthelezi T & Taylor M 2007. Photo-voice as a tool for analysis and activism in response to HIV and AIDS stigmatization in a rural KwaZulu-Natal school. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 19:19-28. [ Links ]

Moletsane R, Mitchell C, De Lange N, Stuart J & Buthelezi T (in press). What can a woman do with a (video) camera. Qualitative studies in education. [ Links ]

Olivier MAJ, Wood L & De Lange N 2007. 'Changing our Eyes': Seeing hope. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart J (eds). Putting people in the picture: Visual Methodologies for social change. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Park E, Mitchell C & De Lange N 2007. Working with digital archives: Photovoice and meta-analysis in the context of HIV & AIDS. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart (eds). Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Pithouse K & Mitchell C 2007. Looking into change: Studying participant engagement in photovoice projects. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart (eds). Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Pink S 2001. Doing visual ethnography. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Prosser J (ed.) 1998. Image-based research: A sourcebook for qualitative research. London: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Ralfe E 2004. Love affair with my isishweshwe. In: S Weber & C Mitchell (eds). Not just any dress: Narratives of memory, body, and identity. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Riggins SH 1994 Fieldwork in the living room: An autoethnographic essay. In: The socialness of things: Essays on the socio-semiotics of objects. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Rose G 2001. Visual methodologies. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Ruby J 2000. Picturing culture: Explorations of film and anthropology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Schratz M & Walker R 1995. Research as social change: New opportunities for qualitative research. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Seshradi S & Chandran V 2006. Reframing masculinities: Using films with adolescent boys. In: F Leach & C Mitchell (eds). Combating gender violence in and around schools. Staffordshire: Trentham. [ Links ]

Smith L 1999. Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Sontag S 1977. On photography. New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Spence J 1988. Putting myself in the picture: A political, personal and photographic autobiography. Seattle: The Real Comet Press. [ Links ]

Spence J & Holland P 1991. Family snaps: The meaning of domestic photograph. London: Virago. [ Links ]

Stuart J 2004. Media matters Producing a culture of compassion in the age of AIDS. English Quarterly, 36:3-5. [ Links ]

Swart J 1988. Malunde: The street children of Hillbrow. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Taylor M, De Lange N, Dlamini S, Nyawa N & Sathiparsad R 2007. Using photovoice to study the challenges facing women teachers in rural KwaZulu-Natal. In: N de Lange, C Mitchell & J Stuart (eds). Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Amsterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

UNCHA 2006. Broken bodies, broken dreams: Violence against women exposed. New York: IRIN. [ Links ]

Van Laren L 2007. Using metaphors for integrating HIV & AIDS education in mathematics curriculum in pre-service teacher education: An exploratory classroom study. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11:461-479. [ Links ]

Walsh S & Mitchell C 2004. Artfully engaged: Arts activism and HIV/AIDS work with youth in South Africa. In: G Knowles, L Neilsen, A Cole & T Luciani (eds). Provoked by Art: Theorizing Arts-informed Inquiry. Toronto: Backalong Books. [ Links ]

Wang C 1999. Photovoice: A Participatory Action Research Strategy Applied to Women's Health. Journal of Women's Health, 8:85-192. [ Links ]

Wang C & Redwood-Jones YA 2001. Photovoice ethics. Health Education and Behavior, 28:560-572. [ Links ]

Weber SJ & Mitchell C 1995. 'That's funny, you don't look like a teacher'. London: The Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Weber SJ & Mitchell (eds) 2004a. Not just any dress: Narratives of memory, autobiography, and identity. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Weber SJ & Mitchell C 2004b. Visual artistic modes of representation for self-study. In: J Loughran, M Hamilton, V LaBoskey & T Russell (eds). International Handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education Practices. Kluwer Press. [ Links ]

Weber S & Mitchell C 2007. Imaging, keyboarding, and posting identities: Young people and new media technologies. In: D Buckingham (ed.). Youth, identity, and digital media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Weiser J 1993. PhotoTherapy techniques. Exploring the secrets of personal snapshots and family albums. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Williams SJ 1998. Malignant bodies: Children's beliefs about health, cancer and risk. In: SW Nettleton (ed.). The body in everyday life. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Willis D (ed.) 1994. Picturing us: African American identity in photography. New York: New Press. [ Links ]