Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Tydskrif vir Letterkunde

On-line version ISSN 2309-9070

Print version ISSN 0041-476X

Tydskr. letterkd. vol.60 n.3 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/tl.v60i3.14451

RESEARCH ARTICLES

The state of Hausa children's folktales and play-songs in Gombe, Nigeria

Bilkisu Abubakar Arabi

Lecturer in the Department of English, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Gombe State University, Gombe, Nigeria. Email: bilkisuarabi7@gsu.edu.ng; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7530-7037

ABSTRACT

In this paper I investigate the state of Hausa children's folktales and play-songs in Gombe, Nigeria to ascertain whether they (folktales and play-songs of children) are still alive and active in this culturally important town in northern Nigeria. My specific objectives are to examine how much parents and their children know of Hausa children's folktales and play-songs and argue that folktales and play-songs are to some extent infused with modern technologies because of globalisation and that mass media has taken over the dissemination of such cultures. To achieve this aim, I employ questionnaires as the instrument of data collection. The subjects for the research are 150 parents and their school-going and out-of-school children aged 20-above and 0-10 respectively. Arguing that globalisation impacts the oral transmission of cultural knowledge more than ever, I adopt technauriture and cultauriture as the theoretical models. Analysis of the data reveals a more than 90% awareness of folktales and play-songs from all respondents. However, some school-going children prefer to watch such oral traditions via satellite rather than listening to a narration as it enhances their language development and nurtures and preserves culture using the paradigm of technology with audio-visual media. The out-of-school children, on the other hand, listen to the narration but are not captivated by it because it only uses the oral means of dissemination. They prefer to watch television and play video games as this educates and entertains using technology, orality, and visuals.

Keywords: children's literature, folktales, play-songs, globalisation, cultauriture.

Introduction

Children are the bedrock of every society because they are the seeds in which culture is nurtured. Children who grow up in a traditional African society always have folktales and play-songs as great tools for socialisation. Culture, therefore, plays a very significant role in shaping the thinking faculty of a child. In modern African society, knowledge transmitted orally changes and adapts to contemporary times. The media-mediated knowledge transmission involving satellite television, video games, and social media platforms, among others, has almost totally replaced its oral counterpart. Today, children's culture is to some extent 'hybridised' because it has taken on a new pattern as new media has created new ways of interrogating the oral culture and making meaning in the computer-mediated society. Sackeyfio (6) points out that the role of African children's literature in the 21stcentury is important for connecting past, present, and future generations through the celebration and expression of cultural heritage. Children universally represent the future and the writers, storytellers, and disseminators for this audience have a commitment to use their crafts in ways that foreground the preservation of African cultural integrity in a globalised world.

Culture is an all-embracing and heterogeneous concept that encompasses every aspect of a man's life and experiences. To further expatiate: culture is expressed in man's religion, language, philosophy, music, dance, drama, architecture, political organisation, technology, and so on (Ajayi 1). To Jungudo (144), culture is the way of life. It embodies the meaning of a tradition. It creates frontiers and boundaries since, through cultural practices, one human society differs from others and insists on its unique identity and autonomy over and against others. However, culture is not static. It is dynamic and changes in time and circumstance from age to age.

Eze and Buhari see culture from the same perspective, defining it as the totality of a group's behaviour derived from the whole range of human activity. Fanon (32), on the other hand, views it as a combination of motor and mental behaviour patterns arising from the encounter of men and women with nature and with their fellow human beings.

Culture and transmission

Cultural knowledge, codes, and norms are transmitted from person to person, from generation to generation and from one group to another via different channels such as family, peer group, school, religious institutions, mass media, and society. Out of the six agents of cultural transmission, I focus more on the family, peer group, mass media, and society in this paper. Be it nuclear or extended, the family is the first point of call where the individual interacts with his/her family members. The family inculcates cultural ideas in a person through direct instruction, as well as emulation of parents, siblings, and relations. It is through the family that children learn the societal norms, values, rules and regulations, and group culture which guide them to conform to societal expectations. Peers have a common identity and great influence on one another in terms of cultural transmission and socialisation. They influence the child's thinking in shaping his attitude towards life. The mass media comprises print and electronic media and performs three complementary functions: education, information dissemination, and entertainment. In this respect, it plays a formidable role in moulding individuals, especially children. It also helps in transmitting different aspects of human culture; what people listen to, read, and watch through print and electronic media mostly leaves lasting impressions on the recipients. Positive and negative cultural traits and practices are mostly picked up by young men and women in their formative years through the mass media, especially audio-visual media.

Cultural elements, however, change over time through diffusion as a result of contact between different groups. Of course, cultural configurations do have originality in terms of values, language, customs, beliefs, and methods of transmission from one generation to another which is what makes a particular people different from another. However, cultural elements are easily susceptible to foreign ideas; they keep changing continually, dropping some of their original characteristics and embracing new ones. The development of science and technology further creates the opportunity for faster diffusion of culture through the existence of communication satellites such as mobile telephones, television, and the internet (Felix 2). This development in science and technology helps facilitate globalisation.

Globalisation

Globalisation gained prominence in the 21st century because of the increasing consciousness of people to relate with one another and share experiences in the world (Felix 2). This increased consciousness is propelled by improvement in the technology of information exchange. To Flint, globalisation is the process of harmonising different cultures and beliefs. Consequently, Bilton defines globalisation as a process whereby political, social, economic, and cultural relations increasingly take on a global scale, which has profound consequences for individual local experience and everyday life. Indeed, the impact is all-encompassing, as there is diffusion of cultures that ultimately affects the economic, social, and political behaviour of the people. This explains why Giddens opines that globalisation brings out human societies which are located far apart under one umbrella called a 'global village'. The possibility is that every happening in this 'village' is shared by all the members, be it in the realm of culture, politics, or economics.

There is no doubt that globalisation unifies the peoples of the world into one orbit and has drastically caused changes. For instance, since globalisation brings about technological advancement, it is pertinent to note that the prominent Ruth Finnegan decided to upgrade her famous Oral Literature in Africa to an online version with the intention of bridging the gap between the old and the new oral literatures in Africa. Kaschula, in his review of the text in Journal of African Cultural Studies, opines that oral literary forms are simply building on the past, adding another dimension to the continual building of the continuum that is linked between the past and the present. It is not a continuum that divides us but a continuum that unites us as a people, underpinned by the cultures and traditions that place us on an ever-changing continuum rather than a linear trajectory of existence. Today one can speak of an oral-literate-techno continuum, and it is to this continuum which Finnegan alludes in her new online book (142-3).

The state of Hausa children

The children of Gombe who the study is focusing on are not exempted from all the instances discussed above. The Gombe Emirate is in the south-western Borno area or region and was part of Lower Benue Valley. The region was earlier inhabited by independent ethnic groups of Bolewa, Jukuns, Tera, Tangale, Waja, and Fulbe. These groups developed a system of economic, social, and political organisation before Bubayero's Jihad that led to the establishment of Gombe Emirates (Arawa 23). Gombe Emirate was established in the 19th century as part of the Fulani reform movement witnessed across Hausaland and beyond. Gombe Emirate, therefore, is part of the Sokoto Caliphate and is in the North-eastern region of Nigeria. The city of Gombe is named after Gombe Abba, the seat of government of Gombe Emirate established by Buba Yero in 1825 (Gombe, et al. xvi). After a long period of political function as the Emirate's municipality, the British colonial government transferred the capital from Gombe Abba to Nafada and later to the modern Gombe town in 1919. Linguistically, the people of Gombe speak diverse languages and adhere to diverse customs and traditions. The Afro-Asiatic and Niger-Congo family of languages are the dominant linguistic group found in the area. The ethno-linguistic composition of Gombe State includes, amongst others, the Bolewa, Fulbe, Tera, Tangale, Tula, Waja, Wurkum, Jara, Dadiya, Cham, Awak, Pero, Kamo, Kushi, and Bangunji. There are also more recent entrants such as the Kanuri, Hausa, Yoruba, and Igbo. In addition to the speaking of all these various languages, the Hausa language does serve the purposes of commerce, interaction, and education at the lower levels of the school system (Abba, et al. 3). However, English remains the official language used in Gombe State and Nigeria at large.

Culturally, the emirs of Gombe accommodate, feed, and clothe more than 12 groups of public and palace singers that entertain the populace within and outside the seat of the palace during ceremonies (Gombe et al. xvi). The Tera have a culture of merry making, songs, and music; the Tangale are great hunters and fishermen; while the Fulani rear cattle and are warriors who use weapons such as bows and arrows, swords, metal helmets, and suits of chain armour (Gombe et al. 42). These cultures form the subject matter and themes of their folktales and play-songs.

The presence of the British colonial administration in Gombe brought about the commencement of western education in 1916. Initially, it was under-patronised and dreaded because it was created by non-Muslims. In order to encourage patronage, the Qur'an and Arabic teachers were employed and the royals were enrolled (Gombe et al. 102). Furthermore, a senior primary school was opened in 1952 and a teachers' college in 1956. After Nigerian independence on 1 October 1960, Gombe witnessed an influx of secondary schools among which were: Teachers' College in Kaltungo in 1961, Sudan Interior Mission (S. I. M.) Secondary School in Billiri in 1966, Government Secondary School in Gombe in 1967, Arabic Teachers' College in Gombe in 1968, Government Secondary School in Kaltungo in 1968, to mention but a few (Abba, et al. 141-9). The established schools gave the people of Gombe and its environs the opportunity to be literate and useful to the modern society.

Recreation and entertainment are part and parcel of the life of the people of Gombe. Abba, et al. explain that recreation and entertainment in Gombe takes the form of orature such as folktales, traditional theatrical performances, legends, myths, proverbs, riddles, songs, tashe (a Hausa traditional pantomime performance that is popular during the month of Ramadan, the Islamic month of fasting), wise-sayings, tongue-twisters, and jokes as well as traditional sports and games like boxing, wrestling, bull fighting, archery, sharo/shadi (a Fulani festival of flogging young men to show courage in order to win brides), langa (a traditional Hausa game of hopping on one leg), horse-riding, hunting, dara (a traditional Hausa game played with cubes which are placed in minor holes in the ground), bird-keeping, and circus-these are what "have characterised and continue to characterise life". However, the upsurge of urbanisation and education brought about the transformation of traditional entertainment forms in Gombe with the following alternatives: "transistor radio, the gramophone, television, newspaper, mobile cinema, and football [...]" (Abba et al. 154). Implicitly, urbanisation and education bring about transformation in the ways oral traditions are being rendered.

Historically, Gombe State was created on 1 October 1996. It was carved out of Bauchi State of which it had been a local government area. It has 11 local government areas: Akko, Balanga, Billiri, Dukku, Funakaye, Gombe, Kaltungo, Kwami, Nafada, Shongom, and Yamaltu Deba. Being located at the centre of the North-eastern region, Gombe is opportune to border with all other five states of the region: Bauchi, Yola, Yobe, Borno, and Taraba. Like Nigeria, Gombe is highly multicultural, multi-ethnic, and multi-lingual. The influx of both foreign and indigenous immigrants into the city is the sole consequence of its recent modernisation whose antecedent is the creation of Gombe State in 1996. Before its creation, Gombe State had many primary and secondary schools that are both public and private with only two tertiary educational institutions: Gombe State College of Health Sciences and Technology and Federal College of Education. Now it has more than 15 additional tertiary institutions: Federal University Kashere, Gombe State University, Pen Resource University, Federal College of Horticulture, Gombe State College of Education, Gombe State Polytechnic, Federal Polytechnic, and Gombe State School for Legal and Islamic Studies, among others. This educational boom is the same or even higher in other sectors such as health, commerce, sports, agriculture, and many more. As a result of this ongoing modernisation project, the city has most, if not all, parts of the country represented ethno-linguistically, for it evidences highly complex and multi-layered ethno-linguistic migratory trajectories. This implies that the children in Gombe State are highly affected by modernisation, thus making them cosmopolitan. They prefer to play with video games and watch cartoons, sitcoms, and children's educational programmes via satellite channels.

It is pertinent to note that the indigenous people of Gombe are not Hausa, even though Gombe is a Hausa-speaking community. The influx of different cultures with the advent of modernisation has replaced the act of storytelling and children's play-songs beside the fireplace in the evenings with satellite televisions where such tales and play-songs are recounted. This is in line with Ashiomole's assertion that "[...] grannies hardly recount tales. They are too busy struggling for sitting space in front of the TV with their grandchildren!" (73).

Furthermore, the social environment of Gombe can be contextualised based on residential areas. The Government Residential Area (GRA) constitutes the area where the elites live and where the school-going children and their parents were derived from, while Bolari, the provincial area which is inhabited by the ordinary man, is where the out-of-school children and their parents were derived from. The children who reside in the latter location have different notions and perspectives of the world and thus have a different understanding of the same socio-cultural environment. Iwoketok rightly points out in her inaugural lecture that "Children's play-songs have a wide distribution and great variety as well. They accompany work, running, skipping, imitation, and sedentary games" (9).1 These play-songs portray the everyday life of the child in and outside the home. This everyday life, which is portrayed through play-songs, reflects the tradition, values, beliefs, and norms of these children and their society. The way children think, play, learn what no one can teach them, solve puzzles, create and recreate, and operate within the actual etiquette of their people. It embodies such items as games, toys, magic, riddles, play-songs, game-songs, lullabies, jokes, tongue-twisters, chants, and so on (9). These cultural practices are the replica of what is obtainable in Gombe State where the children carry out such practices based on their perspectives and experiences. Children living in the cosmopolitan areas carry out such play-songs with a touch of modernisation because they are influenced by the cartoons and Hausa children's cultural and educational programmes they watch on satellite television. The children living in provincial areas, on the other hand, perform it based on their socio-cultural experience.

Various research has been carried out which relates to the present study. Some researchers are of the opinion that Nigeria's children's literature is static, while most researchers focus on the cultural and traditional perspectives which to some extent have slight variations with the Hausa culture. For instance, Onukaogu and Onyerionwu explain that most written children's literature does not possess possibilities of dynamism in terms of the socio-historical context. To them, a children's book written in the 1960s may have the same subject matter, themes, and style as a children's book written in the 21st century. This is unlikely for a children's literature book written in this era of globalisation and mass media awareness. A very good example of this is Muleka and Mwangi's The Folktale Revisited (2020) which combines the use of old and new ways of storytelling while infusing modern and original oral narrative characters that operate using modern gadgets, terminologies, and machinery as members of a dynamic society. Modern children will always give in to the most captivating folktales. In the same light, Ashimole looks at how written literature is competing with mass media for children's attention and consumption because children will always give in to the most captivating presentations on satellite television. Amali pays attention to Idoma folktales and narration which may have similarities and differences with the Hausa version of folktale narration. Furthermore, Sackeyfio, Diala-Ogamba, and Ayodabo share similar perspectives on African children's literature with a focus on Igbo cultural practices of southern Nigeria. Their research focuses on folktales, gender preference, and cultural aesthetics. Storytelling and folktales are an integral part of the African oral society. Folktales usually connect to and illuminate the various cultural and traditional aspects of the society they come from and perform salient functions of entertainment, enlightenment of cultural orientation and traditions of the people, and educating the young on various aspects of society. Folktales, therefore, portray the values and traditions of a society, where children and adults alike learn through the events conveyed. The function of folktales as an oral literature genre cannot be over emphasised (Amali 89). There are lots of educational benefits derivable from them, the most important being their potency as an educational tool. Today's children have abundant opportunities to access this oral genre via technological gadgets available for use in the collection, documentation, dissemination, and promotion of our cultural heritage (95).

Folktale sessions are now presented to the child through television and radio programmes to which parents and their children in Gombe do not give considerable attention. A major challenge with Hausa children's folktales in Gombe is that they have not found/enjoyed the needed attention in documentation, dissemination, and promotion as needed. Considering the above challenge, exposing the school-going children and out-of-school children in Gombe to folktale oral genres would create a lasting, positive impact on them. However, a challenge that may be encountered in the process can be the lack of proper documentation for Hausa children's folktales in particular. Most parents seem to consider it a 'traditional part time art'. This may be why the children prefer to watch movies on television, play video games, and pass time on the internet instead of listening to folktales being retold. Nevertheless, there is hope in revamping the genre. In essence, in this paper I attempt to bridge the gap between the school-going children and out-of-school children by rendering Hausa children's folktales and playsongs in Gombe without altering the original versions in order to enhance language development, remove cultural inhibitions, and create cultural continuity within Gombe State.

Interestingly, through their deep understanding of the challenges faced by indigenous cultures in Africa, Kaschula and Mostert (ii) rescue the situation by discussing the impact of technology on the vitality and transmission of oral traditions because we are in an era where technological developments affect more than ever before the ways societies interact. They help us imagine ways for new digital tools to be harnessed for the benefit of communities with rich traditions of oral performance. In essence, theirs is an urgent global initiative to document and make accessible endangered oral literatures before they disappear without record.

Theoretical framework and methodology

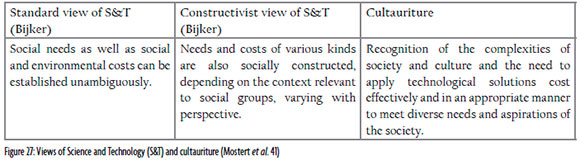

Cultauriture as a theoretical framework is an offshoot of technauriture (Kaschula and Mostert) that aims to deliver a suitable and practical paradigm that captures the dialectics between society, technology, and culture. Cultauriture expands the concept of technauriture into a wider perspective that aims to capture all aspects of the interface between technology and culture, thereby creating a suitable framework for integrating cultural development with the philosophy of technology. It also provides analytical tools for the assessment and evaluation of existing and future applications of technology to cultural modalities (Mostert et al. 43). Cultauriture aims to embrace the aspects of technology, society, and culture that promote cultural sustainability and cultural entrepreneurship. It is the exploration of meaning of culture drawn from the contemporary application of technological and systematic skills to provide knowledge to inform how we understand a community's reaction to contemporary historical arts. This will result in all heritage culture being significant, understood, and appreciated.

Cultauriture treats technology as an enabler for all things cultural, allowing technology to enhance and support the locating of cultural artefacts within relevant social contexts. It offers a paradigmatic and ontological base to develop a strategic and effective approach to the impact of technology on culture. Through developing cultauriture, these complex cultural networks and interfaces can be assessed, adapted, and expanded to meet underlying needs of cultural development and social wellbeing through a process of digitisation using contemporary technologies (Mostert et al. 46).

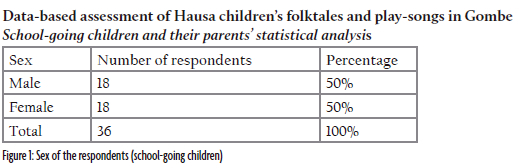

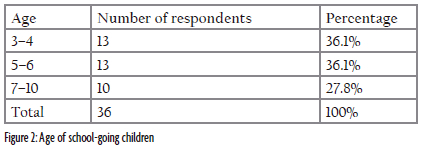

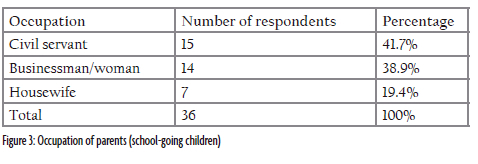

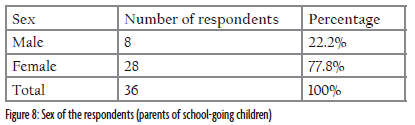

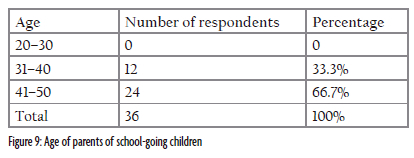

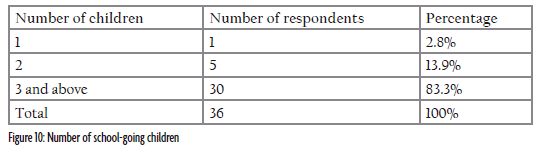

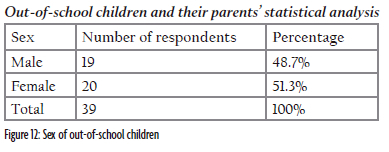

As indicated earlier, in this study I focus on school-going and out-of-school children and their parents. The geographical scope of the study is the city of Gombe where such respondents reside. Locations like Government Residential Area (GRA), Federal low-cost housing estate, and Shongo housing estate are where the school-going children and their parents reside while locations like Bolari, Herwa Gana, and Arawa are where the out-of-school children and their parents reside. I selected three private schools located in the elitist dominated areas and Bolari, Herwa Gana, and Arawa were chosen as non-elitist dominated areas. The information about the state of Hausa children's folktales and play-songs was self-reported via questionnaires which contained a mixture of open-ended and close-ended questions. Although questionnaires can be highly biased, in order to reduce the subjectivity to the barest minimum, I gave out the questionnaires to the selected school-going children in their schools; each pupil was given two copies (one copy for the child which contained the questions for children and another for the parents which contained the questions for the parents) with an explanation on how to complete it. The copies were returned to their schools' head teachers within three weeks. It took us (the researcher and three research assistants) a week to collect the returned copies from the head teachers and verify them.

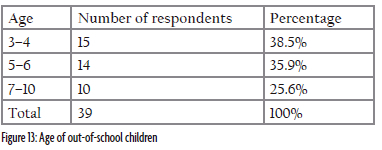

For the out-of-school children, specifically, we went around Bolari, Herwa Gana, and Arawa for three consecutive months, one for each location, administering the questionnaires. Since most of the respondents were illiterate, we read out the contents of the questionnaires to the respondents and immediately filled them out with their responses. To authenticate the entries, we reread the answers to the respondents for clarity and authenticity. All in all, we were able to use 150 questionnaires from both parties. Based on the nature of the work, I have categorised the respondents into four groups: school-going children, parents of school-going children, out-of-school children, and parents of out-of-school children. The data analysis was therefore conducted based on the completion of the questionnaire by both parties (parents and children). The data collected was analysed in order to arrive at an understanding of what the state of Hausa children's folktales and play-songs is within Gombe in terms of awareness, narration, and practicability or usage. The analysis of these components was done qualitatively, but the data is presented quantitatively using simple tables with percentages to code the information. Thereafter, the quantitative data was subjected to quantitative-cum-qualitative analysis. The analysis of the data is mostly qualitative; thus, it is mostly thematic. Worthy of note is the researcher's referral to the data on media consumption of the questions and answers in the open-ended questions section below. In addition, Kaschula and Mostert's technauriture is used side by side with Mostert et al.'s cultauriture for assessing the state of Hausa folktales and play-songs in Gombe State with a view to understand the continuum of three different paradigms that capture the dialectics between society, technology, and culture.

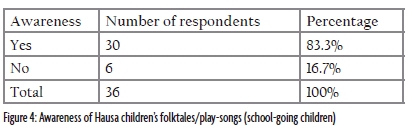

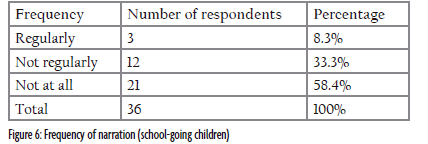

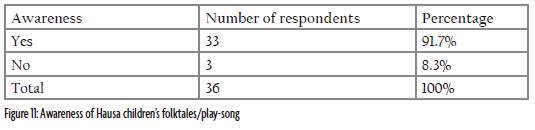

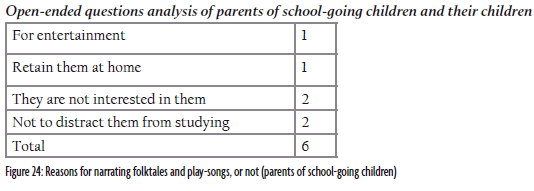

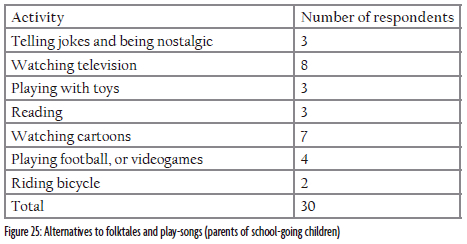

It is interesting that most of the school-going children and their parents are aware of folktales and play-songs meaning school-going- children and their parents have the knowledge that Hausa children's folktales and play-songs exist. In fact, 91.7% of parents and 83.3% of children indicated their awareness of these important oral genres. However, most of the school-going children's parents do not partake of or engage their children in folktale narration and teaching of play-songs at all. A glaring 58.4% of parents and children (more than half of the respondents) indicated that they do not participate in narration. The distance between 91.7% awareness of Hausa folktales and play-songs and 58.4% of not participating in the narration can be said to occur because of social transformations. This is evident in the open-ended questions tables as captured below, where the children listen to folktales using various media. This discovery can be explained by Wise's assertion (qtd in Mostert et al.) that: "[w]e live in societies which are rapidly transforming due, in part, to new technologies. The understanding of the relationship between culture and technology is then quite important to understanding our contemporary world" (39). It is imperative to note that, where there is an awareness of folktales and play-songs in Gombe, they are not prioritised. Parents do not see it as their obligation to teach and narrate folktales and play-songs to their children and to encourage them to use it as a tool for cultural continuity and enhancing language. The frequency of narration of both folktales and play-songs is telling us that something is amiss despite the awareness. This statement suggests that children listen to folktales and play-songs through radio, television, and the internet as captured in the tables of open-ended questions below. This development implies that the data from the questionnaires can be understood when taking into consideration the use of other media by children and parents. This assertion is captured by Slack and Wise (qtd in Mostert et al.) who observe that when "[...] people understand the relationship between culture and technology, they can evaluate the options and negotiate better choices" (39). This relationship is complex, but in its most simplistic form it tries to explain the relationship between technological and cultural determinism which suggests a continuum between the old and the new that is inevitably influenced by the critic's disciplinary background (39). To some extent, Slack and Wise's assertion clearly explains the attitude portrayed by the school-going children and their parents of not practicing the narration but preferring to watch it on the television.

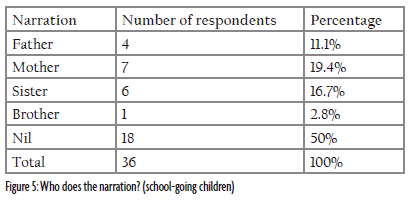

Another aspect that is worth discussing is who does the narration. 50% of the children responded to this question with a nil which means that half of the pupils are aware of folktales and play-songs but nobody within their families has ever narrated these to them. This means that the state of Hausa children's understanding of folktales and play-songs in Gombe is affected by modernisation of technological knowledge, given the nature of the society's trajectory of rapid technological developments where the impact is shared extensively across many sectors in society, from highly positive to more negative results. This outcome created an environment where technological solutions are applied haphazardly and in a non-systematic manner, which most times undermines the innate potential associated with the respective applications. Kaschula, however, "recognised the opportunities that new technologies presented in terms of effective digitization of oral cultures, as a means of preservation, development, and enhancement" (39) of the paradigms between culture and technology. In order to portray the importance of combining the two paradigms together because of the dynamic nature of oral genres and society, Kaschula and Mostert observe that "oral poetry and, by extension, oral tradition is [. ] intrinsic to the human cultural mosaic (1)". Since oral tradition is essential to the human cultural mosaic, Kaschula (qtd in Kaschula and Mostert) coined the word "technauriture in response to the intersection of orality, the written word and digital technology. Regarding its etymology, the 'techn' represents technology, the 'auri' derives from the word auriture, and the 'ture' represents literature'' (3). To Kaschula and Mostert, technauriture serves as a paradigm that offers the producers and practitioners of oral material a "framework for conceptualization of the interface, or the three dialectics between primary and secondary orality and technology" (1).

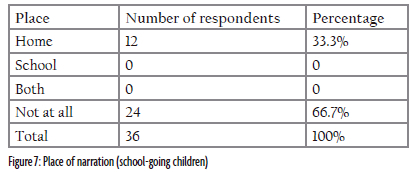

The pace of narration is something else worth mentioning because the home- which ought to be vital in imbibing society's cultural values and norms to the children in my opinion-and school respectively are among the agents of socialisation of a child. In this table, 33.3% of respondents (less than half) selected the home while the school received a 0% response. Likewise, the combination of both home and school recorded 0% and "Not at all" recorded 66.7%, which is the highest percentage. The schools in Gombe do not see the importance of including any of the aforementioned cultures in their curriculum because they see it as something that is out of place and less important in the child's development. Instead, they introduced the watching of cartoons and nursery rhymes that do not portray the cultural practices of the children's immediate environment. It is of utmost importance to consider the social context of the children when drawing up the school curriculum because the oral folktales and play-songs are part and parcel of the social settings in which these children live. As a result of development, the parents and their children start to interact with other people and institutions that influence their perspective in life, where they learn and incorporate the cultural practices of the other participant. In essence, the combination of the oral folktales and play-songs infused with cartoons and nursery rhymes bring about hybridisation which is vital in the development of the child in this modern world.

This challenge is addressed by Mostert et al. who suggest cultauriture, which is an offshoot of technauriture, as the solution. They expatiate: "Cultauriture is the exploration of meaning of culture drawn from the contemporary application of technological and systematic skills to provide knowledge to inform how we understand a community's reaction to contemporary historical arts. This will result in all heritage culture to be significant and to be understood and appreciated" (43). Mostert et al. are advocating for the continuity of oral traditions in a modern world where culture, orality, aurality, and technology are fused together in order to assist in the preservation and development of language and the education of the young ones growing up in a dynamic digital world.

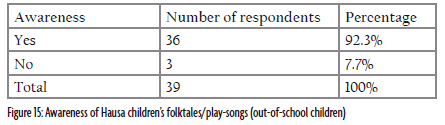

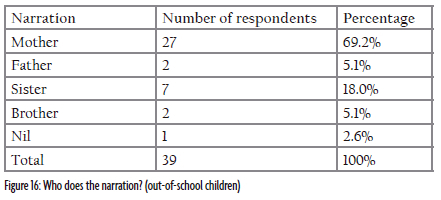

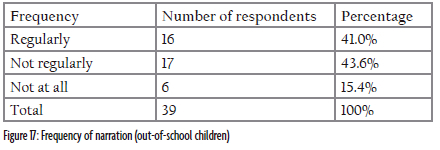

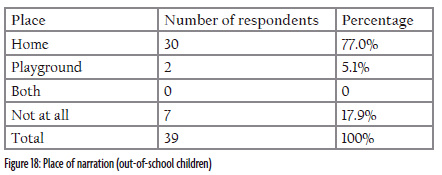

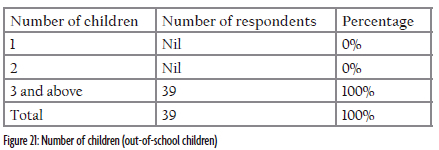

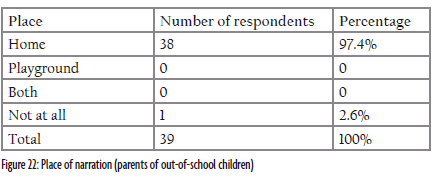

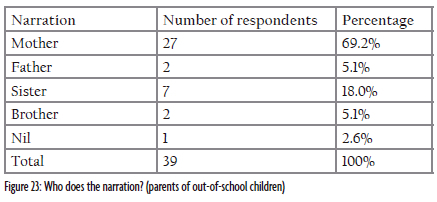

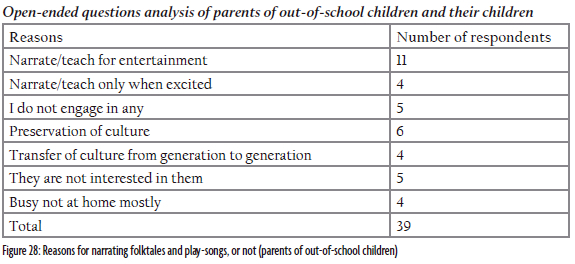

In terms of awareness, 92.3% of out-of-school children and their parents indicated that they are aware of folktales and play-songs and 7.7% indicated that they are not. The frequency of narration figures indicated 41.0% regular narration, 43.6% irregular narration, and a 15.4% response to the 'not at all' option. These percentages suggest that both parents and their out-of-school children are aware of folktales and play-songs and do pay regular attention because the slight difference between regular and irregular narration is just 2.6%. In essence, the percentage shows that the out-of-school children and their parents are putting into practice the narration of folktales and play-songs which suggests that the parents of out-of-school children are advocates of Hausa folktales and playsongs because it is manifest in their responses and those of their children respectively. Nevertheless, the out-of-school parents and their children are not helping the situation because we live in a dynamic and digital world where mass media plays a vital role in our everyday life. Focussing only on the oral aspect of the preservation, sustainability, and continuity of these (folktales and play-songs) oral genres may serve as a threat to the past, present, and future children of Gombe State because such practices do not consider preserving the folktales and play-songs via documentation for immediate and future reference.

Essentially, out-of-school children and their parents should be schooled in this dynamic and digital world where such oral traditions must be harnessed, sustained, and preserved in their original form via the use of technology. Essentially, Mostert et al.'s cultauriture model helps me understand what is going on in the society of the out-of- school children and their parents. In order to change the narrative, harness, sustain, and preserve Hausa folktales and play-songs in Gombe for immediate and future reference in their original form, the adoption of Mostert et al.'s model of cultauriture can go a long way. Overtly, cultauriture:

Endeavours to use technology to overlay the contemporary with the historical to maintain a neutral timeline for the cultural dialogue, and to allow the dialectic between society, culture, and technology to deliver insight into the human journey. Cultauriture does not take sides, it delivers the human journey, not simply to inform but to inform in a contextual manner. (46)

This quote explains the potential of cultauriture to be the new technology that has "the collective frame through which we view the past, present, and future of society and culture" (46).

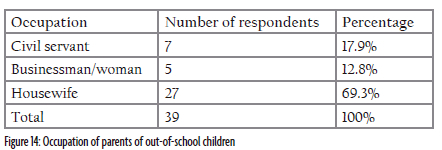

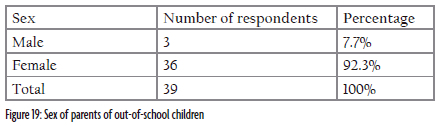

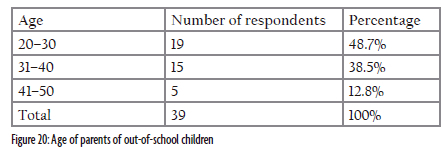

The occupation of the parents also plays a significant role in shaping their children's views towards life, especially the socio-cultural perspective. For instance, the occupational figure of the parents indicates 69.3% of mothers are housewives which is the highest for parents of out-of-school children in comparison to their counterparts in the other group, 17.9% of parents are civil servants, and 12.8% are businessmen/women. In my opinion, the children are cared for and supported by homemakers with limited education and minimal exposure to the advancements of the modern digital age.

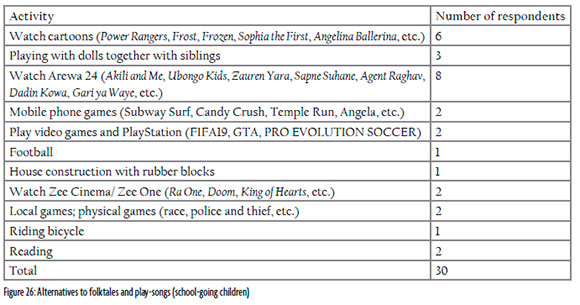

In terms of importance, a considerable number of children (eight out of 30) watch cartoons and children's educational programmes, including a Hausa programme titled Zauren Yara (Children's Corridor) that features children's folktale and play-song narration, demonstration, and dramatization with an embellishment of cultural attires and nuances. This singular act showcases cultauriture in action where it "[.] addresses all aspects of technology, culture, orality and aurality, and how culture is manifest, maintained, and developed in a digital age (Mostert et al. 39-40)". It also aims to bring together the aspects of technology, society, and culture in order to promote cultural sustainability and cultural entrepreneurship (43). The action/attitude of the school-going children puts cultauriture in practice. Arewa 24 is a satellite TV channel that is based in Kano, Nigeria with a goal to provide original content, including comedies and children's programmes that will be created, developed, and produced by Nigerians.

To bring the example home, and excerpt from Mostert et al.'s adoption and application of Bijker's table of distinction between standard and constructivism images of Science and Technology (S&T) to the ideas associated with cultauriture in the table below showcase cultauriture in action.

This table puts Zauren Yara as the recognised complexity that demonstrates cultauriture in action. Arewa 24 recognises the Hausa society's need to apply technological solutions to its culture in an appropriate manner in order to meet diverse needs and aspirations of the society, in the words of Mostert et al. (41). In essence, Zauren Yara effectively entertains and educates the children on language development, cultural preservation, promotion, and sustainability.

On the other hand, the school-going children's responses portray the real breeding of digital children in the sense that the responses of 20 children out of 30 indicated instances of media influence in their lives. This assertion is affirmed in their responses of watching cartoons, playing games via mobile phones and PlayStation, and watching the famous Arewa 24 and Zee One/Zee Cinema. This indicates that the parents of the school-going children are aware of folktales and play-songs but do not partake in the narration, they only encourage the children to watch such programmes via satellite television because it captures the attention of the children more than the oral narrative. Moreover, the use of cultauriture in showcasing children's play-songs and folklore using film techniques unconsciously lures both parents and children into watching it. This entertains and educates the children, thus imbibing the necessary cultural norms the society is willing to pass across.

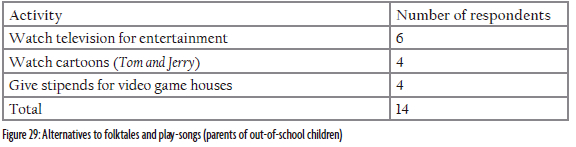

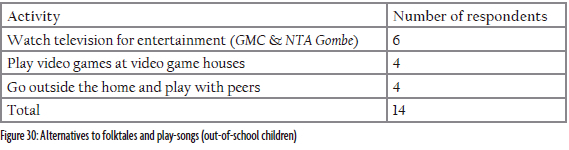

The out-of-school children pose a better chance of sustaining the Hausa children's folktales and play-songs in Gombe, but through the single oral medium. This is apparent as 25 out of the 39 children interviewed engage in folktale and play-song narration. Therefore, the preservation, transfer of culture from one generation to another, and entertainment is carried out using one-way traffic where the audience can only rely on memory for telling and retelling which can fail the narrator anytime. In what seems to be situational irony, the practice of folktale and play-song narration favours the parents over the children in the context of interaction in a digitised world. In fact, the out-of-school children partake in listening to the narration but they prefer to watch television stations owned by the state like Gombe Media Corporation (GMC) and the Nigerian Television Authority Gombe (NTA Gombe) that air cartoons like Tom and Jerry or to pay a stipend to play video games in video game houses which captivates their attention more because the dissemination channel is not only oral but a combination of audio-visual media in a technologized way. More so, the education and entertainment are more satisfying here. This finding thus points to the use/application of technology in sustaining and preserving the culture of folktales and play-songs and corroborates Mostert et al.'s discovery of the ubiquitous presence of cultauriture, serving as an enabler for all things cultural, where technology can "enhance and support the locating of cultural artefacts within relevant social contexts" (Mostert et al. 43). Explicitly, the out-of-school children have an understanding of the paradigms between technology and culture; it is now up to the parents and the state government to locate the cultural artefacts that will be relevant in promoting Hausa children's folktales and play-songs via the media in order to enhance the lives of the children of Gombe.

The out-of-school children's parents do not perceive their children's attitude towards folktales and playsongs narration a problem whatsoever, given the deep syncretism of their culture and modernisation in an ever-dynamic society. The fact is that cultural dynamism is an undeniable fact-whatever explanation is given- and it is clear that this finding indicates that cultauriture has something to offer to the current global discourse on "how technology is applied to culture" which is "invariably empirically-positivist in nature" (Mostert et al. 38). The understanding of the relationship between culture and technology, therefore, is quite important to understanding our contemporary world.

Conclusion

My overarching preoccupation in this paper has been the study of the state of Hausa children's folktales and play-songs in Gombe. I have discovered that globalisation influences the narration of these oral genres. Via the analysis of the data collected, we unveiled that more than 90% of the school-going children are aware of folktales and play-songs but more than 50% do not partake in narration at all as a result of rapid changes and transformation in their society due to new technology. This is a finding which corroborates Wise's (qtd in Mostert et al. 39) argument that our contemporary world can only be understood if we understand the relationship between culture and technology. For example, a nonchalant attitude towards narration shows hybridity in the characters of both parents and children as a result of globalisation. They understand that they can evaluate their options and negotiate better choices. They choose the option of Kaschula's means of preservation, language development, and promotion of oral culture through effective digitalisation of the three-way dialectics between the primary orality, literacy, and technology. However, a challenge was discovered in the place of narration where schools that serve as second agents of socialisation record 0% because they do not incorporate the teaching of oral cultural tradition in the curriculum. A suggestion is advanced of using cultauriture in the curriculum for the preservation and promotion of culture, education, and language development. The out-of-school children on the other hand are also aware of folktales and play-songs and partake in narration but only through oral means. The dissemination through oral means may serve as a threat to the future of these oral genres because the oral resources can easily go extinct as they are not properly documented.

Interestingly, the school-going children who engage in watching satellite television instead of folktale and play-song narration, especially Arewa 24 that features Zauren Yara, demonstrate cultauriture in action which effectively entertains and educates them on language development, cultural preservation, promotion, and sustainability. The out-of-school children enjoy watching television and playing video games more than engaging in narration because the combination of audio-visual media and technology in action is more captivating than oral dissemination.

The state-owned television channels (GMC and NTA Gombe) can adapt children's educational programmes like Zauren Yara in order to bridge the gap between the school-going and out-of-school children. Schools in Gombe should introduce storytelling for pupils to enhance their language fluency and the development of culture and traditions. For example, in the primary school system, cultauriture can be used to document the children's folktales and play-songs and should be incorporated into the curriculum. In addition, I recommend the idea of establishing a grant fund to support the introduction of Nigerian oral literature into the world of digital media by the Gombe State government. The platform will give not only scholars, but also the creators of cartoons and comic books, the opportunity to promote and commemorate the rich heritage of folklore in Gombe and Nigeria at large.

Notes

1 Iwoketok's inaugural lecture is referring to children living in provincial areas in Nigeria, precisely the children of the south-south region as it is the focus of the inaugural lecture. I stand to be corrected but I feel each child applies Iwoketok's viewpoint based on their perspectives, exposure, and experiences.

Works cited

Abba, Sani, et al. Gombe State: A History of the Land iand the People. Ahmadu Bello U P, 2000. [ Links ]

Ajayi, Ademola S. "The Concept of Culture." African Culture and Civilization, edited by S. Ademola Ajayi. Atlantis, 2005, pp.1-11. [ Links ]

Amali, I. Halima. "The Function of Folktales as a Process of Educating Children in the 21st Century: A Case Study of Idoma Folktales." International Conference on 21st Century Education at Dubai Knowledge Village vol. 2, no. 1, 2014, pp. 88-97. [ Links ]

Arawa, Abdullahi Abubakar. "The Imposition of British Colonial Rule and the Establishment of Native Authority Administrative System in Gombe Emirate 1902-1954." MA Thesis. Gombe State U, 2018. [ Links ]

Ashimole, Elizabeth O. "Nigerian Children's Literature and the Challenges of Social Change." Children and Literature in Africa, edited by Chidi Ikonne, et al. HEBN P, 2011, pp. 70-81. [ Links ]

Ayodabo, SundayJoseph. "Culture and Igbo Notions of Masculinity in Nigerian Children's Literature." Tydskrif vir Letterkunde vol. 58, no. 2, 2021, pp. 38-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17159/tl.v58i2.8804. [ Links ]

Bilton, Tony. Introductory Sociology. Macmillan, 1997. [ Links ]

Buhari, A. "The Impact of Globalization on Fulani Culture: A Study of TV Satellite Programme." MA Thesis. Gombe State U, 2012. [ Links ]

Diala-Ogamba, Blessing. "A Study of Archetypal Symbols in Selected Igbo Folktales." Children's Literature & Story-telling, edited by Ernest N. Emenyonu. Boydell & Brewer, 2015, pp. 54-68. [ Links ]

Eze, Dons. "Nigeria and the Crisis of Cultural Identity in the Era of Globalization." Journal of African Studies and Development vol. 6, no. 8, 2014, pp. 140-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5897/JASD2014.0292. [ Links ]

Fanon, Franz. Toward the African Revolution. Grove, 1967. [ Links ]

Felix, Akaayar Ahokegh. "Globalization and the Emerging Cultural Order in Nigeria." Journal of Globalization and International Studies vol. 5, no. 1&2, 2010, pp. 1-8. [ Links ]

Finnegan, Ruth. Oral Literature in Africa: World Oral Literature Series: Volume 1. Open Book, 2012. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0025. [ Links ]

Flint, D. "Why National Pride Still Has a Home in the Globalization Village.'' Globalization Policy Forum. 18 May 2002. https://archive.globalpolicy.org/globaliz/culturaV2002/0318pride.htm [ Links ]

Giddens, Anthony. The Consequence of Modernity. Stanford U P, 1990. [ Links ]

Gombe, Alhaji, et al. History of Gombe Emirate: Documentation of Oral Sources. E-Concept, 2016. [ Links ]

Iwoketok, Enobong Uwemedimo. "Childlore: A Bottom-Up Perspective to Literary Studies and Orature." Inaugural lecture. 11 Dec. 2014, U of Jos, Nigeria. [ Links ]

Jungudo, Mohammed Maryam. "Fulani Culture in a Changing World." Indigenous and Native Studies, edited by J. W. D. Somasundara. Samanala Educational Centre, 2015, pp. 144-55. [ Links ]

Kaschula, Russell. "Oral Literature in Africa." Journal of African Cultural Studies vol. 25, no. 1,2013, pp. 141-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2012.756804. [ Links ]

Kaschula, Russell & Andre Mostert. "From Oral Literature to Technauriture: What's in a Name." World Oral Literature Project, U of Cambridge, 2011. [ Links ]

Mostert, Andre, et al. "From Technauriture to Cultauriture: Developing a Coherent Digitisation Paradigm for Enhancing Cultural Impact." International Journal of Society, Culture & Language vol. 5, no. 2, 2017, pp. 37-48. [ Links ]

Muleka, Joseph Mzee & Julius Kanyari Mwangi, eds. The Folktale Revisited. Asis, 2020. [ Links ]

Onukaogu, Abalogu Allwell & Ezechi Onyerionwu. 21st Century Nigerian Literature: An Introductory Text. Kraft, 2009. [ Links ]

Sackeyfio, Rose. "Culture and Aesthetics in Selected Children's Literature." Children's Literature & Story-telling, edited by Ernest N. Emenyonu. Boydell & Brewer, 2015, pp. 6-16. [ Links ]

Submitted: 25 August 2022

Accepted: 26 July 2023

Published: 13 December 2023