Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Tydskrif vir Letterkunde

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9070

versão impressa ISSN 0041-476X

Tydskr. letterkd. vol.60 no.3 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/tl.v60i3.14691

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Masking death: Covid-19 inspired humour in the everyday orality of a Luo community in Kenya

Rose Akinyi Opondo

Senior lecturer in the Department of Literature, Linguistics, Foreign Languages, and Film Studies, School of Arts and Sciences, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya. Email: rosopondo@gmail.com; https://orcid.org/0009-0006-1960-771X

ABSTRACT

Death, especially death which comes through disease, is often a hard subject that the human mind wishes to bury deep in the unconscious. The lack of ease with impending death eventually finds expression in everyday discourse. In this paper I look at performance of Covid-19 discourse through humour in a short episode of everyday orality of a Luo community in Uyoma Siaya, in Kenya. The performance of the everyday language is textualized to display the aesthetics of contextual language through coinage, jokes, and puns, which manifest as humorous responses to an otherwise dire situation. From the feminising of the disease as Acory Nyar China, literally translated as "the petite Cory from China", to the symbolic naming of aspects of the Covid-19 protocols and verbal jokes about the same, there is an inherent, deliberate attempt to literally laugh in the face of death. The identified aspects of language are treated as metaphorical masks, even as the mask as an object also becomes a metaphor. I employ discourse analysis, which treats language as living social phenomena capable of change, growth, expansion, and adaptation for contextual spatial and temporal expressions.

Keywords: Covid-19, orality, humour, mask.

Introduction

Klimczuk and Fabis (1) describe death as "a state of the total disappearance of life" and dying as "a process of decay of the vital system, which ends with clinical death". The massive number of fatalities from Covid-19 infections, first in Wuhan, China in 2019, then in literally all other parts of the world, led to the declaration of Covid-19 as a global pandemic. The Covid-19 dis-ease (both as disease and lack of ease) and death gripped the world's attention, not only due to its gravity, but also due to the ease with which it spread literally across the world in the era of globalisation through efficient transport networks. The whole world was no longer at ease. The language of fear united the world in the year 2020. The language comprised of daily dire statistics of new infections, total fatalities, few survivals, pathetic overwhelming of medical facilities, and images of body bags and funeral piers, punctuated by concerns about the availability of effective vaccines. It was the discourse of doom and a time in which language demonstrated its power as a key vehicle for the transmission of emerging consciousness and responses to new realities, in this case, dis-ease and death.

In Kenya, the situation was no different and the communal fear was palpable in the statistics of the infected, the dead, and the lucky to survive streaming in on a daily basis through various media. It was literally the language of death all round. Death, especially death which comes through disease, is often a hard subject that the human mind wishes to bury deep in the unconscious. With the declaration of the Covid-19 disease as a global pandemic in early 2020, the world was thrown into a frenzy of activities ranging from survival to submission. For survival, there was an urgent need for various defence mechanisms against the harmful external stimuli, and in this context, the crippling fear of death.

The Luo generally are a Nilotic ethnic group that inhabits Western Kenya, particularly the Nyanza region. The textual material studied herein was collected mainly from the Luo of Uyoma, one of the Luo sub-groups which claim direct ancestry from Ramogi Ajwang', the founder of the first permanent Luo settlement on Ramogi Hill in Yimbo, who belong to the Joka-Jok, the first wave of Luo migrants in Nyanza (Ogot 486). Administratively, the Uyoma people, among whom the studied texts were collected, are in Siaya County. The Luo speak Dholuo which has variant dialects within the Luo of Kenya and also the Alur, Acholi, and Padhola of Uganda and the Nuer and Dinka of South Sudan. The Luo are renowned for incorporating humour into everyday speech, which then finds its way into performed and literary arts. Amuka, Masolo, and Owiti have studied humour in Pakruok' among the Luo, while Michieka and Muaka highlight the humour in Luo speech as acted by comedian Eric Omondi.

Theoretical framework

In this paper, I analyse sampled discourse from the Luo Community of Ogango village in Nyanza that arose from situational contexts, and which exhibit a deliberate bend toward humour in the performance of everyday orality as a response to the Covid-19 pandemic. This is preliminary research into emergent linguistic and literary responses to threatening situations, which should lead to a wider investigation on the coping mechanisms afforded by creative language. This is because everyday orality is a space that affords intuitive and innovative coinages and other linguistics expansions that mirror cultural adaptations for survival. I draw from the Bakhtin school of thought (Selden et al.) which regards language as social phenomena where "words are active, dynamic social signs, capable of taking on different meanings and connotations for different social classes in different social and historical situations" (29). My study focuses on the discursive elements of five selected texts that arose from the social context of everyday language with express references to the Covid-19 pandemic, and which manifested the deliberate employment of humour.

In this paper I focus on discourse from the Covid-19 situation in the performance of everyday verbal intercourse amongst this community and interrogate the same as negotiations with death through the mask of humour. The performance of the everyday through orality is textualized to display the aesthetics of language through coinage, jokes, and puns. This performance is captured in the language that was encountered in oral communicative moments and which then become entrenched in the verbal corpus of the speech community. In the preface to Orality: The Power of the Spoken Word, Furniss notes that: "The oral communicative moment is of interest because it is in understanding its dynamics that we can understand the how and the why of transmission of ideas and values, information and identities" (xi). What Furniss refers to as the "communicative moment" is interpreted here as that moment of creativity and spontaneity that characterises oral performance. The product of this performance can be isolated to be of interest in the interrogation of phenomena beyond the surface function, which would be covert communication of intentions, expectations, and other situations that make up everyday intercourse between people in a speech community. The reflections in this paper are based on the communicative moments as experienced by me as the researcher in the oral performance of the texts under study within the span of a two week stay in the rural village of Ogango. One text (Acory Nyar China) was obtained from both phone conversation and non-participant observations of conversations, while the other four texts were obtained from non-participant observation of conversations. After each encounter, I probed the speakers on the texts' origins and meaning. The texts encountered were then analysed for their function as humorous responses to an otherwise dire situation.

Analysis of the texts was done within the framework of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). Wodak and Meyer (2) define discourse as "anything from a historical monument, lieu de memoire, a policy, a political strategy, narratives in a restricted or broad sense of the term, text, talk, a speech, topic-related conversations, to language per se" (3). The texts reflected upon are speech acts in the form of contextualised conversations, which seem to offer a sustained trend that captures the cultural and social moments. Fairclough describes CDA as the "analysis of the dialectical relations between discourse and other objects, elements or moments as well as the analysis of internal relations of discourse" (4). The words and phrases are examined in relation to the social occurrence of the Covid-19 pandemic. CDA sees "language as social practice" (Fairclough and Wodak 4), with Fairclough reiterating that CDA studies social interactions by focusing on their linguistic elements "to show up their generally hidden determinants in the system of social relationships-as well as hidden effects they may have upon that system" (5). I therefore seek to unearth the underlying humour in the texts in relation to the implications of disease and death presented by Covid-19 pandemic in this paper.

This study, in which I focus on an instance of performance of orality in the contemporary culture of this community, falls within the broad field of oral literary studies, and is informed by the socio-political and situational contexts of Covid-19, with orality being the basic medium of interaction with our social reality that incorporates all the relationships that enter and exit it.

Everyday Covid-19 discourse as text

I posit that the everyday conversations around the Covid-19 pandemic in this community forms a corpus of heightened use of language with notable distortions, adaptations, coinages, and expansions of words and phrases that provide textual landscapes for the study of intentionality in discourse creation and performance which goes beyond the surface of ordinary communication. According to De Certeau, the act of speaking "operates within the field of a linguistic system; affects an appropriation, or re-appropriation of a language by its speakers; establishes a present relative to a time and place; and posits a contract with other (the interlocutor) in a network of places and relations" (xiii). Everyday discourse creates publics around phenomena through communicative action that can be dialectically opposed to prior meanings attached to the same phenomena. This is exemplified here by the conferment of new meaning to words and phrases in day-to-day speech. In his Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959), Goffman notes that "when the individual is in the immediate presence of others, his activity will have a promissory character" (2). The verbal texts scrutinised herein were collected from instances of ordinary conversations in which the writer was a non-participant observer of the dialectism in these conversations which belong to the everyday discourse.

Data collection is a systematic process of gathering observations or measurements. Traditional data sources are often structured and empirically determined. However, everyday conversations-face-to-face or through technical devices-and overheard commentaries offer unique opportunities as unconventional data sources which can be exploited for distinct phenomena. These instances enable insight into emerging trends in real time and can be studied, as done in this study, to interrogate phenomena of literary interest and as platforms for further research.

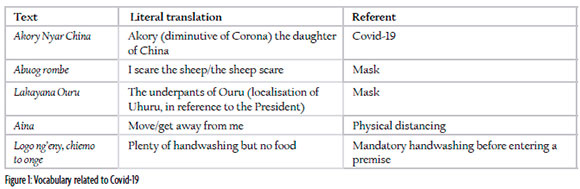

From instances of participant observation from telephone conversations and non-participant observation of situational conversations over a two-week period in the rural village, the following vocabulary emerged as coinages with regard to new realities presented by the Covid-19 pandemic:

For this study, the phrases were captured aurally, and then noted in the phone notebook for study. This is because they occurred when no recording device was activated. Written notices using some of the phrases were also photographed and archived for study.

Conversations offer effective spaces for discourse analysis as they are characterised by spontaneity and immediacy of performance that point to urgent and current mindsets about phenomena. During a phone conversation with an ailing friend during the enforced lockdown of Nairobi City and its environs, my query as to the friend's health was responded to thus: "I'm well, it's this Akory Nyar China with her hard eyes who has locked me indoors". This threw me off balance because I had no idea who Akory Nyar China was, and it was clear from the response that it is a person. My inquiry as to who this is was met with laughter and a revelation that it is a reference to Covid-19. From this conversation emerged the appropriation of the name of the virus 'Corona' to the name of a person. Further, the name is feminised by the prefix 'a' which renders a diminutive stature to the name it is appended to. This is commonly done to accord an equivalent of the English petite to the woman in reference and is a term of endearment created from her name. As such, in this community, the oral performance of names like Arosy (from Rose), Apolly (from Pauline), and Aterry (from Teresa/Theresa) are found in situations of endearment that can be either filial or seductive.

The ideological association of Covid-19 with the female gender is instructive and there are two possibilities for this development. Either the term "Corona" seems to readily lend itself to a female name, which would be a simplistic explanation, or the disease is deliberately feminised to draw it into a particular communicative discourse as a lesser gender. The endearment of the name that suggests playful seduction furthers the second argument. This would make this renaming a deliberate seduction of Corona-now an anthropomorphic term-to take the hedge off her viciousness. It seems to be an oral performance of power over the virus. From the telephone conversation, the speaker refers to Corona as having "hard eyes". This is a literal translation of the Dholuo statement "gi wange matek", making use of the phrase "wang' teko" (hardness or stubbornness). This refers to someone who is daring and can do what they wish, especially the unpopular. This gives Corona, the personified disease, a characteristic of negative and destructive stubbornness shown by her audacity to lock grown people and whole populations indoors!

The requirement to wear a mask on your face when in public took this piece of protective wear from the hospital setting into the public domain. This new reality forced the coinage of a term for the mask worn in public. While attending a burial in my rural home, the mourners encountered men manning the entrance who directed them to a handwashing station and reminded everyone without a mask to wear one before entering. The instructions were variably: "Dani, ruak abuog rombe" (Granny, put on your mask), "Ere aboug rombe nil" (Where is your mask?), and "Onge donjo ka iongegi abuog rombe" (There is no entry for you if you don't have a mask).

The phrase "abuog rombe" is a coinage which invariably means "I scare the sheep", referring to the action of scaring sheep when you wear the mask, or 'the sheep scare', a noun-phrase naming the mask. It is a combination of "buogo" (scaring) and "rombe" (sheep). Sheep in this community are often regarded as foolish animals. It is common to hear an insult referring to a person as exhibiting sheep-like qualities. "Ifuo ka rombo" (you are as foolish as a sheep) or "wie pek ka wi rombo" (his head is as thick as that of a sheep) are common expletives among the Luo. The implication here would be that the sheep, who are foolishly gullible, would be scared by the look of people who now look strange wearing masks. This not only captures the estranging aspect of the mask, but also the seeming foolishness of covering a large part of one's face in public.

In one particular situation, an old woman, while rising to depart from my house after a visit said, "miya uru lakayana Ouru na" (give me my Ouru's underpants) in reference to her face mask which she has misplaced while eating. Upon inquiry, I was informed that that was another recently coined term for the mask. "Lakayana" means innerwear in traditional Dholuo. It is rarely used today because this speech community now commonly uses the corrupted "sirwari" (from the Kiswahili "suruali") to refer to this piece of inner clothing. Lakayana was a small strip of leather that women tied around their waists to cover their frontal private parts. As such, it nuances a very private aspect of the human anatomy. In the evolutionary lexicology, afuongo or abongu replace lakayana. These are now made of cotton and other synthetic textiles to be worn inside outer garments, and which now cover the entire private area in the advent of exposure to western cultures. However, these words are being phased out of ordinary discourse. They are now used mostly as metaphors or for other deep reflections by elders or for insulting. Subsequently, only few people, particularly the elderly, are aware of and use the word lakayana. Further, it is considered a taboo word to be spoken openly in public and often euphemisms are used as its referent. In this coinage, the mask is referred to as Uhuru's underpants using the most impactful word that points to nakedness.

At the local health centre in the rural village where the I had gone to see a relative, I overheard a conversation between a woman and a young man who was about to sit next to her on a bench while waiting to see the doctor:

Woman: Owada aina. (Please get away from me)

Young man: mos dani, ok aparo ni aina ni kae. (Sorry, granny, I didn't remember that "get away from me" is here)

Woman: Sani wadak kode. (Now we are living with it)

From this conversation, it emerged that the word "aina" (get away from me) was used to refer to the required spacing in physical proximity due to the Covid-19 protocols, commonly referred to as 'social distancing'. This word was commonly used with an exclamatory tone in conversations of jest or anger when one told the other person to 'get out of their hair'. Its appropriation to mean physical separation was meant to address to the disease itself, telling it to 'get away from us', to 'get out of our hair' as it was separating people, a negative development that affects the community.

Humour in the Covid-19 discourse as defence mechanism

Humour, often in the form of jokes, is held to be "a contrast of ideas, sense in nonsense, bewilderment and illumination". Theodore Vischer (qtd in Freud 1617) defines joking as the ability to bind into a unity, with surprising rapidity, several ideas which are in fact alien to one another both in their internal content and in the nexus to which they belong. A joke is the arbitrary connecting or linking, usually by means of a verbal association, of two ideas which in some way contrast with each other. The Platonic theory of humour, which labels it irresponsible and unfit for progressiveness, is discarded in this reading in favour of both the Freudian relief theory and the Kantian incongruity theory of humour. This is because, as Morreall (4) notes, "in the Relief Theory, laughter is a release of pent-up nervous energy. In the Incongruity Theory, humour is the enjoyment of something that violates ordinary mental patterns and expectations". Both theories can explicate the humorous incongruities in the coinages as well as their laughter-induced relief prowess. The core of humour is words and words find their immediate and often fluid expression in oral discourse.

Culturally, mandatory handwashing-logo-is associated with preparation to eat. It is common to hear the Luo say "wan e logo'" (we are at a handwashing) to mean they are eating. The imposed handwashing and sanitising as part of the Covid-19 prevention protocols distorted the common function of hand hygiene and elicited a new reference to bring out the incongruity in the exercise. Interestingly, this text was first encountered as a jocular proverb "logo ngeny, chiemo to ongë' (plenty of handwashing yet there is no food). Afterwards, young children performed it as a riddle thus:

Riddle: Plenty of handwashing but no food?

Answer: Corona!

Riddles are characteristically incongruous and the relationship between the posed riddle and its answer points to both the observed similarities and the distortion of expectations. These creative oral performances which were woven into the performance of the everyday are important in presenting the deep-seated humorous masking of the Covid-19 pandemic. The association of handwashing with eating only is a humorous way of expressing the distortion of its functionality by Covid-19. Now the handwashing is done even where there is no food to be eaten.

Sigmund Freud, one of the early proponents of a defence mechanism, proposes that a defence mechanism is an unconscious psychological mechanism that reduces anxiety arising from unacceptable or potentially harmful stimuli. Thoughts of disease and death are potentially harmful stimuli because of their fatality in the human psyche. Perottta (1) defines defense mechanism as "psychological processes, often followed by a behavioral reaction, implemented to deal with difficult situations, to manage conflicts, to preserve their functioning from the interference of disturbing, painful and unacceptable thoughts, feelings and experiences". One of the most prevalent collective defence mechanisms is humour, as seen in both the proverb and riddle about handwashing.

The intensity of handwashing at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic from early to mid-2020 manifested the palpable fear of death and subsequent performances of self-preservation like handwashing. In Kenya, it is instructive to note that the Presidential Order of Service, the Uzalendo (Patriotic) Award which recognises acts of service to humanity, was given to a nine-year-old boy for his innovative hands-free handwashing invention during the 2020 Jamuhuri Day celebrations. This signifies the fact that every handwashing act was a statement of dis-ease and a reminder of death. The created riddle thus effectively shifted the mind from death to the humour of the illogical handwashing where there is no food, successfully masking the thoughts of imminent death through contaminated hands. By resolving the riddle of this strange handwashing, the community comes to terms with the new reality through the mediation of creative orality. Language is herein used to effectively take away the edge from a worrying aspect of emerging reality.

Rizutto (12) notes that for Freud "words are a plastic material with which one can do all kinds of things. There are words which, when used in certain connections, lose their original full meaning, but regain it in other connections". In the coinage abuog rombe, the literal translation into the ambiguity of "I scare sheep" or "sheep scare" do not directly refer to an interaction with sheep but to the alterations (read distortions) of facial features by wearing the mask. The intention is to draw attention to the funny look of the mask wearer rather than the reason for wearing the mask. The laughter elicited effects relief of anxiety over death and a purging of negative energies is achieved by the distortion of meaning. In the phrase "lakayana Ouru", the humour of referring to the mask as the underpants of a sitting president is both provoking and subversive of power. The president is the ultimate symbol of authority in a state and is ideally the protector of his citizens. His 'exposure' in the phrase is a subversion of power and a humorous expression of the same. The president seems helpless in the face of Covid-19 and this helplessness is succinctly captured in the mask that the citizens are now 'forced' to wear. The president's vulnerability in the face of a ravaging dis-ease is projected onto his nakedness in a humorous manner. This joke at once captures the protest against the enforced wearing of the mask and the association of the president with powerlessness. The crudeness of this expression in the conversation takes off the edge of the pain of death that is attendant to Covid-19. The humour here draws attention to the incongruity of the variables paired together: underpants and mask.

Freud looks at speech as a vital key to the unconscious. This, I can argue, is due to the power of the spoken word. Furniss explains that this power can be realised in "how people's daily experience as individuals is articulated and evaluated, and then shared and amended or refined, until a growing force of common views emerge as an articulated combination of statements about how the world 'really' works [...]" (18). The shift in the meaning assigned to the Covid-19 coinages that alienate them from their 'original' meaning and reference points to the power of the spoken word to direct and redirect shared communication as seen in the phrase "lakayana Ouru". There are various things to note in this speech performance. Firstly, the speaker is an old woman who can get away with a taboo word in a general audience. Secondly, the association of the mask, worn on the face, and reference to the underwear of a sitting president and a symbol of ultimate authority in the land, points to the subversion of power and the expression of disgust with the enforced wearing of masks. The expression is humorous. Thinking of wearing the president's underpants on your face and the resultant laughter hides the implications of disease and death, but also draws attention to the psychological underpinnings of the mask. Its enforcement (complete with not wearing it in public being declared a criminal offence punishable by law) is embodied in the person of the president and disgust with it is manifest in his exposure. Reference to the mask as abuog rombe shifts from its ominous meaning of self-preservation from impending death to its humorous referent of scaring of sheep when one wears a facemask.

Art creates community through the communication of shared aesthetics. However, other than communication of emotions through external agencies, artistic expressions offer spaces for reflection, deflection, and inflection that are necessary for survival. In a Freudian sense, a clearly discernible artistic defence mechanism like the use of humour would then heighten a sense of security in both individuals and the community, in turn forming a coping mechanism. The use of humour emphasises the importance of language in power play where the speaker seeks to bring a threatening phenomenon under control by taking away its fearful aspects through the creation of laughter. The performance of everyday life within the context of creative language is treated as text for interrogation of communal psyche in the appropriation of power over the Covid-19 pandemic through creativity of humour which is indicative of the importance of verbal art.

The Covid-19 mask as metaphor

Britannica (Wingert) defines a mask as "a form of disguise or concealment usually worn over or in front of the face to hide the identity of a person and by its own features to establish another being". It goes on to posit that "this essential characteristic of hiding and revealing personalities or moods is common to all masks". Culturally it is associated with spirituality where, in the performance of rituals, the target spirit is to be present in the mask, therefore the wearer of the mask must disappear for the spirit to appear. This is the associative function of masks appropriated by the performed arts.

The mask in itself is a concrete object that functions as a cover that prevents access to what is behind it without eliminating it altogether. This means that the viewer of the mask still has a distant consciousness of the personality behind the mask but the personality before the mask-Goffman's "front" (Goffman 16)-is what is foregrounded and looms large to command visual and psychological attention. The mask therefore acquires a personality of its own and enters the discourse space as a participant. This enables it to create a negotiated space for dialogue with the unseen but known. Masking, therefore, is an act of concealment, a functional deception like the mask of Calliope, the Greek goddess of tragedy.

We can read a dual metaphor in the discourse of the Covid-19 pandemic. It speaks of fear and death on one hand, and of control and resistance on the other. Goffman (12) looks at the mask as a conception of self, which becomes a second nature, but which incidentally forms the truer self of the person behind it. The mask as a metaphor captures an individual's movement from "sincerity to cynicism" where initially it is worn to prevent the spread of a deadly virus-an aspect of sincerity-but later gains the symbolism of an alternative weakened and cowering self: the cynicism offered by our vulnerability to the Covid-19 virus, which when accepted gives us, ironically, control once again. It is in this context that the object of the mask has been accorded nuances of scare in the phrase "abuog rombe" and exposure of nakedness in "lakayana Ouru".

These associative factors seem to inspire creative coinages that occur in the communicative moments that at once anthropomorphise the mask and elevate it to symbolism.

Conclusion

In this study I have reflected on the use of humour in words and phrases in everyday communication within the context of Covid-19. The collected phrases and words which were coined to refer to Covid-19 and its attendant protocols and shifts in lifestyles have been analysed as indicative discourses of humour with special referent to the threatening phenomenon of a global pandemic.

The vocabulary selected for the study seemed to function as humorous responses to an otherwise dire situation, thereby providing the necessary mask through which death can be looked at and lived with. Inherent from the onset of the uncertainties surrounding the pandemic, is a discernible refusal by a majority of the members of this community to be rendered hopeless by Covid-19. From the feminising of the disease as "Acory Nyar China", to the symbolic naming of aspects of Covid-19 protocols and verbal jokes about the same, there is an inherent, deliberate attempt to laugh in the face of death.

The usage of these coinages in everyday discourse entrenched their integration into the community's linguistic corpus and normalised discourse. The words and phrases discussed herein kept the mind from literal death through humour. Conclusively, we can deduce that the creative power of oral language in devising and establishing novel usage of existing vocabulary for both lexical and semantic incongruities bring out humour, as well as the significance of verbal interactions in recreation of meaning in response to emerging contexts.

Works cited

Amuka, Peter Sumba Okayo. "The Place of Deconstruction in the Speech of Africa: The Role of Pakruok and Ngero in Telling Culture in Dholuo." African Philosophy as Cultural Inquiry, edited by Ivan Karp & D. A. Masolo. Indiana U P, 2000, pp. 90-103. [ Links ]

De Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall. U of California P, 1984. [ Links ]

Fairclough, Norman. Language and Power. 2nd ed. Pearson, 2001 [ Links ]

Fairclough, Norman & Ruth Wodak. "Critical Discourse Analysis." Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, edited by Teun A. van Dijk. Vol. 2. Sage, 1997, pp. 258-84. [ Links ]

Freud, Sigmund. Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. Read, 2014. [ Links ]

Furniss, Graham. Orality: The Power of the Spoken Word. Palgrave MacMillan, 2004. [ Links ]

Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. U of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Centre, 1959. [ Links ]

Klimczuk, Andrzej & Artur Fabis. "Theories of Death and Dying." The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Social Theory, edited by Bryan S. Turner. Wiley-Blackwell, 2017, pp. 1-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118430873.est0084. [ Links ]

Masolo D. A. "Presencing the Past and Remembering the Present: Social Features of Popular Music in Kenya." Music and the Racial Imagination, edited by Ronald M. Radano & Philip V. Bohlman. U of Chicago P. 2000, pp. 349-402. [ Links ]

Michieka, Martha & Leonard Muaka. "Humor in Kenyan Comedy." Diversity in African languages, edited by Doris L. Payne, Sara Pacchiarotti & Mokaya Bosire. Language Science Press, 2021, pp. 559-76. [ Links ]

Morreall, John. "Humor, Philosophy and Education." Educational Philosophy and Theory vol. 46, no. 2, 2014, pp. 1-12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2012.721735. [ Links ]

Ogot, Bethwell A. A History of the Luo-Speaking Peoples of Eastern Africa. Anyange, 2009. [ Links ]

Owiti, Beatrice. "Humour in Pakruok Among the Luo of Kenya: Do Current Theories of Humour Effectively Explain Pakruok?" International Journal of Linguistics vol. 5, no. 3, 2013, pp. 28-42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v5i3.3369. [ Links ]

Perrotta, Giulio. "Human Mechanisms of Psychological Defense: Definitions, Historical and Psychodynamic Contexts, Classifications and Clinical Profiles". International Journal of Neurorehabilitation vol. 7, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1-7. [ Links ]

Rizutto, Ana-Maria. Freud and the Spoken Word: Speech as a Key to the Unconscious. Routledge, 2015. [ Links ]

Wingert, Paul, S. "Mask.". Encyclopedia Britannica. 10 Feb. 2020. https://www.britannica.com/art/mask-face-covering. [ Links ]

Wodak, Ruth & Michael Meyer. "Critical Discourse Analysis: History, Agenda, Theory, and Methodology 1." Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, edited by by Ruth Wodak & Michael Meyer. Sage. 2009, pp. 1-33. [ Links ]

Submitted: 5 September 2022

Accepted: 26 July 2023

Published: 13 December 2023