Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Tydskrif vir Letterkunde

On-line version ISSN 2309-9070

Print version ISSN 0041-476X

Tydskr. letterkd. vol.59 n.3 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/tl.v59i3.12535

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Battling statues enter into dialogue at the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga

Kasongo Mulenda Kapanga

Professor of French and Francophone Studies in the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures in the School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia, USA. E-mail: kkapanga@richmond.edu; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1719-2312

ABSTRACT

In this article I analyze the political bifocal discourse that the display of Congolese political figures reveals at the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga (State House of the Province of Haut-Katanga) in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo that was inaugurated in 2018. The display reflects the potency of a discourse dictated by a period of time's circumstances reflective of new ways of thinking. It is the performative self-affirmation focusing on the politics of proximity and not exclusively that of distanciation seen in its worst form in ethnic cleansing. Within the global atmosphere marked by public demonstrations heightened by the death of George Floyd (1973-2020) calling for the toppling of monuments honoring Robert E. Lee; Cecil Rhodes; George Colston's in Bristol, England; King Leopold II in Belgium; honoring busts of King Leopold next to Doha Beatriz Kimpa Vita's; and Moïse Tshombe's next to Patrice-Emery Lumumba's, inevitably leads observers to question the arrangement. It articulates in plain sight a twofold political discourse positing, on one hand, its unitary aspiration, on the other hand, the uniqueness of the Katanga province with its strengths, its expectations, and its vulnerabilities. My analysis relies on Michel Foucault's concept of discourse, on Pierre Nora's notion of lieux de mémoire, and François Hartog's idea of presentism. Hartog's presentism accommodates an analytical exercise that uncovers a discourse of continuity allowed by the necessities of the present. Specific discursive elements become building blocks towards the aspiration to social stability reflected and re-articulated throughout the materiality and rationalizing of figural representations.

Keywords: memorialization, discursive analysis, Michel Foucault, ethnic cleansing, Pierre Nora, monuments, presentism, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Introduction: The hunt for some statues

Recent discovery informs us that a black woman known by her servant name of Angela or Angelo and brought to Virginia in 1609 along with seventeen other Africans kidnapped from the shores of the Kongo Kingdom in Angola, was the first black slave-although other accounts dispute that -to set foot on colonial American soil.1 At the 400th-year commemoration of the creation of the Commonwealth of Virginia in 2019, Angela was remembered at public events in speeches by both political and civil rights leaders, including President Donald J. Trump, in reports by major news outlets, and in writings by commentators and historians such as the Malawian historian Paul Tiyambe Zeleza. The latter's long commentary entitled "The Original Sin: Slavery, America and the Modern World" underlines Angela's symbolic relevance linking her fate to the struggles of today's Black America. From stark anonymity, Angela has turned into a symbol of endurance, resilience, and immolation. Her very existence has become the subject of further enquiries and opportunities to ponder over the ethical dimension of slavery in the birth of the United States which extols itself as a beacon of freedom. In an ironic twist and in reference to the colonial era, what was celebrated with impressive monument is nowadays scrutinized and sometimes reduced to empty self-congratulatory acts of "lost causes". As power shifts, so does the paradigm that underlies the constellation of celebratory claims. In the last four to five years, localities around the world have embarked on a soul-searching process questioning why some colonial figures were honored with monuments. Demands to remove statues of Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902) on South African campuses, campaigns to get rid of the Confederate Monuments in Virginia and elsewhere in the United States, demonstrations to topple George Colston's statue from the Bristol harbor in England, or those of King Leopold II of Belgium, indicate a worldwide shift in public demand for accountability on the colonial legacy (see "Belgium: King Leopold II statue removed in Antwerp after anti-racism protests"). The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, and especially the death of George Floyd (5 May 2020), further reinforced the scrutiny of overt racial supremacy by publicly disavowing the message or intention of some monuments that directly extolled slavery and cast colonial expedition in a positive light.

This article forms part of my ongoing research for a book manuscript on the popular discursive elements of nation consolidation as captured in public monuments in four regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Lubumbashi-Likasi axis, Grand Kasai, Grand Kivu and the capital, Kinshasa.

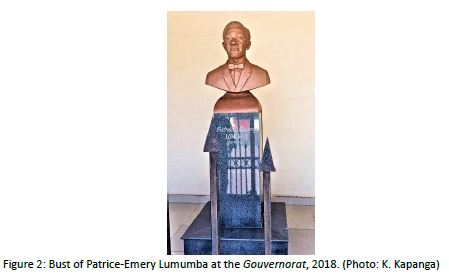

One ought to contrast the indignation to topple "offending" figures with the display of statues representing Congolese political figures at the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga (State House of the Province of Haut-Katanga) in Lubumbashi that was inaugurated in 2018. At the start of my field research, the renovated place displayed an odd arrangement of political figures that rose eyebrows in reference to historical facts. King Leopold II appeared in the company of Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, the Congolese St Anthony (1684-1706,), and Simon Kimbangu (1887-1951); two sworn enemies, Moïse Tshombe (1919-1969) and Patrice-Emery Lumumba (1925-1961) stood next to each other. The peculiar sight raised many questions almost spontaneously. Are these monuments direct visual expressions of collective unifying dreams, or rather the result of visual corrective lenses of what the Congolese society admittedly aspires to? Are monuments unreliable vessels that go to great pains to mimic the potency of time sensitive discourses which shape political, social, economic, and religious idealizations? What message, if any, could come out of this display?

In this article, which will evolve in four parts, I focus on the potency of a discourse-here on the monuments-caught in a flux of significant changes forced by circumstances leading to renewed ways of thinking and conceptualizing society as the site of power dictates. It stands as a reflection on the politics of memorialization by way of monuments as displayed at one of the most public areas in the city of Lubumbashi, namely the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga, complemented by visits to other sites in Likasi, Kinshasa, and Kananga, places of interest that are part of a larger research project.

The first one will focus on these monuments as allegorical structures allowing institutions of power to memorialize events or individuals within a discourse shaped by the possibilities of the moment. This may result from mere internal or localized deliberations from a society's ideals crafted into discreet discursive claims. Recourse to Michel Foucault's notion of discourse and its theorization on society will provide a framework to the reflection on this odd arrangement of Congolese political figures.

The second part will discuss the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga display by scrutinizing the politics of interrogating Congolese past events and their enduring effects on society while dramatizing an imagined correction as a strategy to affirm its integrity and allowing an overt expression of specificity. If it is relevant to interrogate the toppling of Cecil Rhodes in South Africa and in England, it is equally relevant to interrogate the positioning of King Leopold ll's statue next to Kimpa Vita's, and Tshombe's next to Lumumba's in the very city one tortured to death the other.2

The third part examines the relevance of what can be referred to as relational capital to sustain the ideals of unity by projecting minimized rifts between personalities which may have led to widespread instabilities and hostilities (Demetriou and Wingo 342).

The fourth part is an attempt to highlight the potency of the present conditionalities that re-examine the power of the monuments in the here and now, presentism as François Hartog would call it, as conduit and conditions to a discourse of continuity. The contingent necessities of the present dictate new arrangements that become innovative building blocks in search of social stability reflected by the way old rivalries are re-articulated throughout the materiality of representation in a revived unitarist logic that memorializes political figures of historical notoriety.

Monuments as allegorical structures of discourse

The presence and the position of these statues posit the coexistence of two tenets: Katanga's distinctiveness and the Congo's claim to its territorial integrity. The observation of the display of statues occurred in a three-year span stretching from summer 2017 to summer 2021. At the start of my research, the statue display included Belgian royalties, Kimbangu, Kimpa Vita, Soeur Anuarite, Émile Wangermée, and other Congolese political figures such as Lumumba, Tshombe, Mobutu Sese Seko, Joseph Kasavubu, and Laurent-Désiré Kabila. The July 2021 display at the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga had a reduced setup with the colonial figures glaringly absent, but the Congolese ones still standing firm. These alterations to the monument may have been caused by changes to internal politics as well as by the global disavowal of brutal colonial history and slavery. Grasped as a continuum between periods, the display simulates a political dialogue extending to "bitter" enemies as popular history will rightly recall it. These monuments and their display offer a contextualized narrative that transcends, accompanies, and even neutralizes mere and plain abstraction of convoluted notions (virtues) such as courage, sacrifice, and prosperity. At the same time, over a few months, it was witnessed as a reassessment of the rationale and the presence of certain statues honoring individuals known to have operated in situations of dubious ethical values such as human trafficking. Scrutiny of history as recorded by the conquerors yields different conclusions and accepted explanation on the matters. Two schools of thought are in competition, namely the "removalist and preservationist arguments" (Demetriou and Wingo 342).

In Foucault's view, discourse is defined as strings of speech that permeate every articulated area of knowledge of society that analytical method can parse into discreet and even contradictory epistemic elements. It is worth quoting Carla Willig's summary of Foucault's discursive analysis that explains its relevance in a case like this one, an interpretive instrument enabled to delineate discursive elements that could be re-combined to project a different imagined world, albeit purely platonic. She writes:

Foucauldian discourse analysis is concerned with language and its role in the constitution of social and psychological life. From a Foucauldian point of view, discourses facilitate and limit, and enable and constrain what can be said, by whom, where and when (Parker, 1992). Foucauldian discourse analysts focus upon the availability of discursive resources within a culture-something like a discursive economy-and its implications for those who live within it. Here, discourses may be defined as "sets of statement that construct objects and an array of subject positions" (Parker, 1994a: 245). These constructions, in turn, make available certain ways of seeing the world and certain ways of being in the world. Discourses offer subject positions which, when taken up, have implications for subjectivity and experience. (154, emphasis in original)

The concept is also closely related to power as it immerses into social interaction. For Foucault: "Furthermore, power does not function to repress individuals, but produce them through practices of signification and action" (Willig 163-4). Willig refers to Bogue's work by asserting that signification, unlike theories of representation, does not refer to actions and things, but are themselves actions which "intervene with things" (147). The display of these political figures participates in the performative form as discursive practices in the Congolese context; the politics of the local as an episteme calls for a new repositioning, albeit theoretical in a redacted partnership even of once mortal enemies. Composite in its structural dimension, the discourse straddles two trends, one internally or locally turned, and the other outwardly or nationally oriented. As Willig rightly observes, Foucault pays attention between discourse and institutions and ideological formulation may prompt to take the shape that incorporates power (154). Hardly linear, parsing such a discourse meanders through claims in examining past decisions while arguing for the primacy of intrinsic values such as courage, compassion, sacrifice, and justice as presumed to be indisputable metrics of heroism.

At first, the display articulates apparently contradictory statements reflective of subjective positions as a discourse of materiality that addresses substantive matters of unity and division in a framework that mingles both the past and the present. The statues and their arrangement articulate in plain sight the availability of a political discourse in its unitary aspiration while at the same time affirming inwardly its proper attributes that underline the uniqueness as Katanga province with its expectations, its strengths, and its vulnerabilities.

The display's vulnerabilities are dependent on the conditions of possibility that reiterate and defy past assumptions while boldly articulating the future of a new or renewed signification. In the aftermath of the Congo's civil wars from i960 to 1964, an estimated 100,000 were killed, including Lumumba and the UN General Secretary Dag Hammarskjöld and thousands of Congolese were internally displaced. Peace restoration went through a process that Kirk Savage (200) likens to a therapy. Earlier inflicted wounds such as the splits caused by Tshombe's secession or Gabriel Kyungu's and Nguza's ethnic cleansing commanded a restorative narrative represented by the positioning of apparent archenemies but projected in their amended postures for the benefit of the nation. The display bears witness to the functioning of the mechanisms of political and economic infrastructures through selected practices as it appeals to a genealogy of historical events and occurrences, albeit in a position of sharp contrast. Although one can see such a display of monuments as intuitively contradictory, absurd, and almost arrogantly provocative, the ultimate intent brings into focus significant occurrences familiar in the region, the relevant relation framework determined by political implications wherein its existence and survival are rooted, and the attempt at ushering a message with specific appropriate discursive elements. Linearity or causality are not the issue here, but the historicity of the moment takes precedence as reshaped by the constraints of stability. Quite pragmatically, such a re-arrangement, doomed to fail, mirrors the real accommodation that took place when Tshombe became Prime Minister under Kasavubu's presidency from July 1964 to October 1965. Through this new accommodation, the old paradigm of confrontation is suggestively replaced by one fitting re-positioning, albeit imaginary. The need to avoid confrontation leaves room for a complex collaborative process that minimizes frontal exclusion. The display acts as a space that reflects the paradigm of historical and ideational layers whereby the present's viability is heavily determined by previous occurrences that leave traces in their materiality that are woven and absorbed into imagined and positive discursive pronouncements. Included is the uniqueness of Katanga in the national framework.

As in the Foucauldian analysis, the public monuments so centrally located in the heart of the commercial district facing the Catholic cathedral St Pierre et Paul, and the newest and tallest building in the province, the high-rise shopping mall Hypnose, are a multi-faceted discourse: modern amenities, public history, gentrification of the space, and creation of new public spaces. The display may also be viewed as a discourse of legitimation of that space as a stronghold of the nationalist leader that Laurent Kabila (1939-2001) is said to have been and its participation into the power matrix and its complexity. Power being relational, it allows those components to enter into a dialogue of accommodation or discontinuity. In spite of, or even because of Katanga's troubled secessionist past, the display stands as a shared continuity discourse that gauges the value of moments and embarks on a project to create a harmonious or empowering affirmation towards a unified national ideal from dispersed epistemic parts. One could even infer that the right way forward lies at the nodal point that links democratic values to the social ethos, which explains the recurrent clashes between CENCO (Conférence Episcopale Nationale du Congo, or DRC's Catholic Bishop Conference) and the political power. These are two diametrically opposite pulls-one points towards a unitary objective, while the other one is recoiling on the regional one. At the surface level, one merely sees the periphery resisting the center, and, on the other, both strands are engaged in a unitary exchange wherein the local is granted space to accommodate its claims and its statements while fully participating in the larger claim of nationhood. The rigidity of the earlier period wears away and submits to new plans. That is, a 50-year span of history partly co-opted by Mobutu regime policies (19651997) that not only erased any public display of previous historical figures but lapsed into an exclusionary personality cult: dictatorial memorization as Pierre Nora would call it ("Between Memory and History: Les Lieux De Mémoire" 8). The decks were cleared of any colonial and post-independent celebrated historical figures. What prevailed in this context in the deliberate attempt at nation consolidation is the reconstruction of an idealistic whole made from "sifted and sorted historical traces" (8). These traces in the form of political figures turn into basic building blocks that historical logic would expectedly enter into confrontation, but intuitively trek into a complex collaborative process that minimizes frontal exclusion. Their display strongly mimics the unitary narrative that blunts past and even lethal rivalries in such a way that they become discursively active agents of cooperation in opposition to their earlier staunchly confrontational claims.

Discursively, the site of the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga comes out at first as a collection of "remains" of codified elements in their most significant version arranged within a unitary discourse. These coalesce into a meaningful claim with accommodation between dispersal discursive elements that drastically curtail hostile frontal clash. However, the components that enter in this encounter are not at first sight uniform but rather strategically participatory in a reconstructed statement of unity.

Repositioning statues as re-imagined Congolese history

The setup aims at appealing to emotions stoked strategically in a constructive way. The Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga becomes the site where the national history is articulated through the arrangement of political figures. One aspect that draws anyone's attention is the message that the space and the monuments articulate, that is, the material conduit through which specific statements are to travel. The first imagined aspect is the legitimation of the Congo State. At this juncture, relying on Nora's interpretation, the display highlights and puts into focus a set of stated ethical principles removed from possibilities of confrontation. Nora's following passage illustrates the spatial setup populated by the political figures that the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga that links the concrete-statues are visible and depict historical figures-to significant emotional reactions:

un lieu de mémoire dans tous les sens du mot va de l'objet le plus matériel et concret, éventuellement géographiquement situé, à l'objet le plus abstrait et intellectuellement construit. Il peut donc s'agir d'un monument, d'un personnage important, d'un musée, des archives, tout autant que d'un symbole, d'une devise, d'un événement ou d'une institution. (Les lieux de mémoire 28)

a site of remembrance in every sense of the word goes from the most material and concrete object, eventually geographically situated, to the most abstract and intellectual object. This could be about a monument, an important personage, a museum, archives, as much as a symbol, a motto, an event, or an institution.3

This purely abstract statement escapes the intellectual parsing to turn into a formulation that finds full meaning only as a collectively shared experience but grounded in the present and steered towards the future. Testimonies are presented, re-articulated, and imagined along new patriotic principles that many have existed in earlier instances. Nora further comments:

Les lieux de mémoire, ce sont d'abord des restes. La forme extrême où subsiste une conscience commémorative dans une histoire qui l'appelle, parce qu'elle l'ignore. [...] Musées, archives, cimetières et collections, fêtes, anniversaires, traités, procès-verbaux, monuments, sanctuaires, associations, ce sont les buttes témoins d'un autre âge, des illusions d'éternité. (Lieux de mémoire 28)

Memory sites are first and foremost the remains. An extreme form where a remembering consciousness in a history that calls it, because it ignores it. [.] Museums, archives, cemeteries and collections, feasts, anniversaries, treaties, official reports, monuments, sanctuaries, associations, these are physical testimonies from another age, illusions of eternity.

The urge to unify brings into play contradictory trends, statements, ideals, and, like in a rewritten play, ascribes newer idealistic roles to their representatives.

The second aspect is rather denunciative and lies in the scrutiny of memorialized events during both colonial and post-colonial periods. The saddest cases include tortures inflicted on Kimpa Vita (end of the 17th century) and Sister Anuarite Nengapeta (1939-1964). One needs to remember that Nora has of late been one of the public intellectuals who theorized on the practice of memorializing events or people in an age where the function of the representation sculpture as practiced before the invention of photography no longer justified the necessity of representation as the main objectives by sponsors. If internal scrutiny of the odd display of the statues is attempted, it also allows the privilege to abstractly reconstruct what had not worked in the past by re-imagining and seizing the opportunity to project a restorative version. His historical perception at the start was chiseled on the firm belief of the history/non-history binarism that relegates a major part of world societies to the margins. He writes: "Among the new nations, independence has swept into history societies newly awakened from their ethnological slumbers by colonial violation" ("Between Memory and History" 7).

Such coexistence as a project and anticipatory design takes the liberty of putting side by side statements, characters, symbols, and even slogans within specific contexts that, at worse, eliminate or neutralize exclusionary intents by either minimizing them or emptying them of their disruptive aggressivity. lt is an opportunity to re-imagine a different political landscape in a land that has a sour share of deep ethnic tensions. ln other words, the competitive edge is blunted by neutralizing any space for destructive counter-discourses. The Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga discourse straddles a two-tract path of which one unabashedly affirms the Katangese identity-that Erik Gobbers calls "imagined Katangan identity"-while inscribing it within the unitary context of the nation.4 Several examples illustrate this identarian paradox, especially the monument of L'Identité Katangaise and that of Laurent Kabila three kilometers from the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga on the road to Luano International Airport. As a matter of fact, the Statue de l'Identité Katangaise circle, representing the Grand Katanga unity and sharing the same identity in an unbreakable bond, features two men and two women holding hands. The monument offers a counter-discourse of some sort vis-à-vis the unitary impulse inscribed in the display of statues at the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga.

Since Mobutu's fall from power in a political arena fractioned by scores of political parties, "co-optation", political alliances, and counter-alliances reflect a new paradigm for re-alignment that Martin Kalulambi Pongo calls "co-optation politics" (25). In its worst form, it is akin to François Bayart's "authoritative restoration" (510). It is within this new mindset that a statue of Tshombe towers facing the Post Office Building (Place Tshombe), the center of the city of Lubumbashi. Romain Gras describes his presence framing in a historical way as follows:

Un jour de juillet 1960, ce fils de l'un des hommes d'affaires les plus fortunés du Congo belge annonçait la sécession de la province cuprifère du sud du pays, avec le soutien actif de l'ancien colon. L'aventure durera trois ans, mais elle marquera le Katanga pour plusieurs décennies. Soixante années plus tard, que reste-t-il de ce passé si singulier, outre cette statue aux côtés de laquelle une poignée de photographes se proposent d'immortaliser les passants? (n. p.)

On a July 1960 day, this son of one of the most fortunate businessmen in Belgian Congo proclaimed the secession of the copper province in the south of the country, with the active support of the old colonizer. The adventure lasted three years, but it would leave a lasting impact on the Katanga province for several decades. Sixty years later, what is left from this unique past, beside this statue by the side of which some photographers offer to immortalize a few passers-by?

It was not by coincidence that Tshombe's monument and that of Kasavubu on the Place Kimpwanza in Kinshasa were both inaugurated on 29 May 2010, the eve of the 50th anniversary of independence. Both instances of memorialization are tightly linked, namely the celebration of freedom from colonial rule and the recognition of the two politicians in the history of the nation for the role they played almost a half a century before. Radio Okapi, the UN-sponsored media outlet in the DRC, draws closer these two events in an article titled "Cinquantenaire: inauguration: des monuments de Kasavubu et Tshombe" (At the 50th Anniversary of Independence: Inauguration of Kasavubu and Tshombe Monuments). One passage reads as follows:

Le président Joseph Kabila a inauguré mardi 29 juin à Kinshasa, le monument de Joseph Kasavubu, premier président de la République Démocratique du Congo, à l'occasion de la fête du cinquantenaire de l'indépendance de la RDC. Le monument du président Kasavubu est érigé dans la commune de Kasavubu, à la place Kimpwanza (NDLR: Indépendance en Kikongo, langue parlée majoritairement dans les provinces du Bas-Congo et du Bandundu). Marie-Rose Kiatazabu Kasavubu, l'une des filles du président immortalisé, a assisté à cette cérémonie. [...] Pendant ce temps, à Lubumbashi, au Katanga, le monument de l'un des anciens chefs du gouvernement, Moïse Tshombe, est érigé au centre-ville. Cet ouvrage qui immortalise ce personnage de l'histoire politique de la RDC sera inauguré en même temps qu'une fontaine spéciale mardi 29 juin dans la soirée.

President Joseph Kabila has inaugurated on Tuesday, June 29 in Kinshasa the monument of Joseph Kasavubu, the first president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, at the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the country's independence. The Kasavubu monument is erected in the commune of Kasavubu, at the Kimpwanza (Independence in Kikongo, the language spoken by the majority of the people in the provinces of Bas-Congo and Bandundu). Marie-Rose Kiatazabu Kasavubu, one of the immortalized president's daughters, attended that ceremony. [.] In the meantime, in Lubumbashi, in Katanga, the monument of one of the former leaders of government, Moïse Tshombe, was erected at the center of the city. This work that immortalizes this person from DRC's political history was inaugurated at the same time as special fountain on Tuesday, July 29 in the evening.

The unitary aspect is evidenced by the accessory national colors (blue, red, and yellow) that surround Tshombe's monument and not the Katangese white, green, and red. This testifies to the timely relevance of internal and external dynamics that combined into a discourse of cooperation. Lived experience has fostered an all-encompassing ideology prone to stoke the unitary impulse.

In the face of local recognition, some kind of political accommodation whose meaning is given the shape of certain gestures embodied by monuments may be seen as part and parcel of this therapy as much as it may constitute a political strategy. This would fall in line with other areas whose semiotic value is obviously the celebration of unity, of peace, and the right to dream for a prosperous future. Such unitary monuments that graphically and symbolically accompany ideological tenets enshrined in the national consciousness may take several forms. In the Congolese post-independence context, the well-known Joseph Kabasele's song "Indépendance Cha-Cha" celebrates and lists prominent politicians, including Tshombe and Lumumba. The end of the first stanza runs as follows:

ASORECO na ABAKO

Bayokani Moto moko

Na CONAKATna CARTEL

Balingani na FRONT COMMUN

Bolikango, Kasavubu

Mpe Lumumba na Kalonji

Bolya, Tshombe, Kamitatu,

Oh Essandja, Mbuta Kanza.

ASORECO and ABAKO

They agreed like one person

With CONAKAT and CARTEL

They like very much the FRONT COMMUN

Bolikango, Kasavubu

Also, Lumumba and Kalonji

Bolya, Tshombe, Kamitatu,

Oh Essandja, Old Kanza. (my translation; emphasis added)

Highly charged felicitous unifying events rush back in a restorative gesture to re-inscribe the problematic past into a celebratory positive present. Mimicking a kasàlà-like naming litany, the new realignment of major players is publicly called and displayed, so that integrity can not only be highlighted, but a rebirth to a better destination can be fostered.5 As expected, unity and brotherhood are underlined and celebrated as dictated by the imminent granting of independence by Belgium after the Round Table where the end of tutelage was dubiously negotiated.

Denouncing may be a prelude to a constructive and corrected move with a second impulse pointing to unitary claims. The main force is the ethos of unity that encompassed all goodwill politics that seeks peace and calls for closeness under which everyone can work in harmony. Unity begets stability which will neutralize countless achievements or will trigger any unplanned unraveling of what society may have laboriously achieved. Promoting such an ethos and encasing it in publicly conspicuous symbols is likely to blunt ethnic chauvinism and control old demons that left wounds and deep scars on the local region and the country as whole. It is not only articulated by the statues themselves, but in a rather significant way by the strategic and relational physical positioning of the major historical figures. Like a dinner gathering, the position of one at the table has deep implications and reflects the relationship two persons or a group of people entertain with the hosting party.

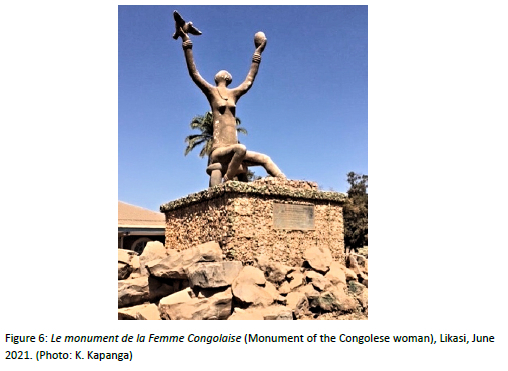

The last aspect is the heroization of Laurent Kabila. These two impulses are diligently made to coexist and magnified further by three components. The unitary element made up of three components of this accommodation is illustrated by the presence of three main sites: Kabila's statue on the highway to the Luano Airport from downtown Lubumbashi, the Shilatembo site, and Monument de la Femme Congolaise in Likasi. The elder Kabila remains in a symbolic way the linkage between the two local and national impulses captured by the monument. His induction into the Congolese political pantheon as national hero who died for the country's integrity far from his native Katanga finds its most obvious materialization in his mausoleum in Kinshasa. Kabila's memorialization goes from the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga to his gigantic statue at the entrance of the city from Luano Airport. It has supplanted old Mobutu's big posters strategically placed at the entrance of any Zairean (Congolese) city, as well as the ubiquitous billboards extolling Mobutu's presidency at the entrance of every city. Realpolitik accommodation or a deceitful strategic stand? Why now and what was behind the logic? For the past two decades, Katanga's leadership over the nation was marked by the presidencies of Kabila I and II. When the elder Kabila's ideological preferences were inscribed within the unitary framework championed by earlier nationalist politicians such as Lumumba and even Mobutu, the younger Kabila, who could and should be commended for preventing the disintegration of the nation amidst a myriad rebellions (2001-2006), launched a decentralized regimen where provinces had a wider margin in matters of local political, economic, and cultural decisions. The discourse of unity does not only involve individuals, but extends to sad events to the national body-physically and metaphorically represented by the body of a desperate and wailing woman-as recorded in eastern Congo. Laurent Kabila's monuments articulate the unitary discourse by ushering the slain president to the national hero status alongside Lumumba as I will later argue.

In Likasi, 80 miles north of Lubumbashi, the Monument de la Femme Congolaise dramatizes a unitary appeal, some kind of Mater Congolesa Dolorosa that appeals to all, Congolese first. The monument raises the signified to a more general but concrete level as a reminder of the sexual brutalities undergone by thousands of women in eastern Congo. Remembrance of untold brutalities foisted on Congolese women strongly shows that therapy on many levels is warranted and ought to be hastened as the monument so clearly shows: the torn body requires more than justice that the Pleureuse at Le Palais de Justice in Kinshasa is so gesturally and affectionately seeking. The idea of the Congolese woman's body that is scarred by a constellation of phallic conspiracies as well as outsiders' onslaughts morphs into a larger symbolic signifier of national consolidation. It transcends other identarian confines and elements of differentiation to turn into a recognizable motif in the consciousness of most of the Congolese beyond any emotional reactions and calls for action. It also brings to mind the towering picture of the 2018 Nobel winner Dr. Denis Mukwege, his Panzi Clinic, and the echoes of strident appeals by writers, artists, and other public piers of this indignation.6 The singer Djuna Djanana's Mwasi ya Congo does just that (Radio Okapi, "RDC: A Bukavu, l'artiste musicien Dadju s'engage à lutter contre les violences sexuelles faites aux femmes").

The nation as a body needs to be restored to its unitary status, not to be repaired by one man as Colette Braeckman's L'homme qui répare les femmes (2016) suggests, but through a collective action of atonement, corrected behavior, and above all retributions against perpetrators. By calling for a Criminal International Court for the DRC, Dr. Mukwege verbalizes the distraughtness of countless women indiscriminately sacrificed on the altar of profits and financial gains in seeking justice, an outcry overwhelmingly shared by the Congolese.7

The relational capital and Laurent Kabila's heroization

Post-independence Katanga politics harbors salient dark spots: Tshombe's secession attempt and the 1990s ethnic cleansing of Kasaians. These specters still loom large in people's consciousness (Dibwe dia Mwembu, "L'épuration ethnique au Katanga et éthique du redressement des torts du passé"; Gorus). Beyond the display and the optics, and even despite the various pro and counter discourses, lies the importance of the relational capital which dictates the pace and the tone of the performance of any nation as a unitary project. Katanga politics, for what it is on the national level, has always had in its background the looming shadow of Tshombe viewed as the father of decolonized Katanga and the instigator of the Katangese identity which sometimes takes precedence over the national impulse. At times, his memorization may be an ambivalent reminder where positive messages alternate with dark spots stoking sad memories.8

Sandrine Vinckel's summary in an ethnographic case study published in 2015 between what she calls "Katangese" and "Kasaian" populations provides a snapshot of the unprecedented ethnic cleansing of Katanga's Kasaian population whose labor for four generations contributed to make the province a giant mining industry at once referred to as Africa's Ruhr region, or as Jules Cornet (1865-1929) called it, "un scandale géologique" (a geological scandal):

Between September 1991 and June 1995, Katangese authorities committed and supported the coordination of mass violence against the non-native Kasaians in Katanga province, Democratic Republic of Congo. More specifically, Baluba from North Katanga who were members of the militia of the UFERl (Union des Fédéralistes et Républicains lndépendants), a political party ruled by two Katangese leaders-Gabriel Kyungu wa Kumwanza, the then governor of Katanga, and Nguz a Karl-l-Bond, the then prime minister of the country- orchestrated the systematic assault of Baluba from Eastern Kasai, their initial target, before extending attacks against all Kasaians and non-natives living in Katanga. (Vinckel 78)

Till today, the tension has not entirely died down as it had once under President Mobutu's feisty regime, in part for lack of direct confrontation against the identity policies that some provinces have embraced; the severe economic downturns in the Great Kasai region exacerbated by the Kamwina Nsapu phenomenon (2016-2019); and the lack of adequate public infrastructure such as roads, electricity, and running water, conditions that have pushed Kasaian youth, both skilled and unskilled, to migrate to supposedly green pastures of the Congolese economy: Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, Likasi, Kolwezi, and Kasumbalesa. The malaise in Katanga is also attributed to the slow pace of economic recovery; the rivalry between the rich south (Haut-Katanga and Lualaba) and the north, where the Baluba are concentrated; and the failure by the national government to assure reliable security without which no viable progress could be expected. What Andrew McGregor wrote in the Refworld on behalf of the UNHCR in April 2014 remains true today as he casts serious doubts on the secession aspiration as the raison d'être of the Bakata Katanga (which means let Katanga go its separate way) movement, whether by the Kyungu Mutanga Gédéon's wing or Ferdinand Tanda lmena's one: "In one sense, the secession issue provides political cover to criminal groups like Katanga's Mai Mai militias, which otherwise have little in the way of a political ideology and do little to gather popular support as a legitimate secession movement might be expected to do" (1). The "space for negotiation" meant to trigger a "bottom-up-reconciliation" between the two communities championed by Donatien Dibwe dia Mwembu ("Relectures de l'histoire et transformation des rapports entre les Katangais et les Kasaiens du Katanga" 128-36; "La réharmonisation des rapports entre les Katangais et les Kasaiens dans la province du Katanga (1991-2005)" 129-32), as Vinckle notes, has raised very little appetite from the power stakeholders beyond scanty claims and empty symbolic gestures. ln the embracing of the two impulses, Prime Minister Sama Lukonde has called a conference at the highest level in order to find lasting solutions. Each side fears any further destabilization and the devastation likely to be triggered in the region and the whole country with the possibility of spilling beyond the region to Zambia and Angola. However, in recent years, very little seems to have prevented any deadly incursions by the militia group Bakata Katanga into public spaces. The presence of the Mai Mai militia acts as reminders of possible destabilizing events flaring up anew. As recently as February 2021, eleven deaths resulted from the militia attack on the Kimbembe military camp on the outskirt of Lubumbashi City. Gras pointedly reported as follows:

Ces derniers mois, le Katanga-démantelé en quatre provinces distinctes à la faveur d'un redécoupage, en 2015-a vu resurgir de vieux fantômes. Longtemps au cœur du jeu politique sous la présidence de Joseph Kabila qui, comme son père avant lui, avait confié des postes stratégiques à des ressortissants de la province, l'ancien Shaba (le nom du Katanga entre 1971 et 1997), terre natale de deux présidents de la République, a vécu un début d'année agité.

These last few months, Katanga-divided into four distinct provinces due to the redistricting in 2015-saw old demons coming back to life. For long at the heart of the political actions under the presidency of Joseph Kabila who, like his father before him, had given strategic positions to those originating from the province, former Shaba (the name of Katanga between 1971 and 1997), native land of two presidents of the republic, lived a troublesome year. (n. p.)

The FCC-CASH coalition that allowed President Félix Tshisekedi, an ethnic Kasaian, to enter into coalition with Joseph Kabila's political family was not only short-lived but perceived in certain circles as the repudiation of Katangese at the highest level and a threat to its identity. Nevertheless, Laurent Kabila has a new role created and widely popularized with the hero's mantle at the highest level of national consciousness. In the midst of this tension, the unitary motif is reactivated with the support of three different presentational ways. The entrance to the city of Lubumbashi from Luano Airport is graced with the towering statue of Laurent Kabila overlooking the sprawling city. The site ideologically links up with the Lumumba Mausoleum that is being built in Shilatembo at the very site where Lumumba, Okito, and Mpolo were brutally murdered, cut into pieces and burnt by a threesome Belgian firing squad at the behest of his enemies that included Tshombe; Kasavubu; Mobutu; King Baudouin; and Colonel Louis Marlière, the Belgian security officer and advisor to Tshombe in charge of eliminating Lumumba in Elisabethville.

Although still under construction, the Shilatembo site features the two giant figures of Lumumba and Laurent Kabila concurrently coming off the ground. Several characteristics are intentionally cast as similar: the unitary ideology they both held, the ultimate sacrifice they made for the Congo, their meteoric appearance on the political scene where local and international enemies hunted them down; and especially the reasons of their assassination concocted by a combination of local and outside international interests.9

Through Shilatembo, what Nora calls "reserves of memory" becomes the foundation for a new projection of more conciliatory stances among major political figures. We are catching at work a national re-imagining process, a building of a consciousness that is facing old memories of acts of extreme violence that affected various sections of the Congolese society (Nora, "Between Memory and History" 7). Laurent Kabila's mausoleum in Kinshasa establishes and confirms his status as a national hero who has become a component of the city landscape.

Presentism as path to continuity discourse

Researchers in many areas have long reflected on the relationship between history and memory, including the historian Hartog. ln his essay Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and the Experiences of Time, Hartog offers an original perspective where he distinguishes three regimes of historicity: historicity of epistemes as dramatized in Iliad and Odyssey, historicity of the modern that plots events towards a better destiny, and presentism as historicity focused on an ongoing situation. As Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann summarizes what he calls Hartog's "deceptively simple argument" about historicity, "our contemporary experience of time is essentially 'presentist'. The present regenerates the past and the future only to valorize the immediate. In our 'crisis of time,' the present has become 'omnipresent'" (535). Hartog's reflections fit fairly well the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga discourse by focusing on the present. He writes: "Today, enlightenment has its source in the present, and the present alone. To this extent-and this extent only-there is neither past nor future nor historical time, if one accepts that modern historical time was set in motion by the tension between the space of experience and the horizon of expectation" (203). He also underlines the fact that the relation with the past is submitted to amnesiac and simulation treatments, which explains the non-respect of the verisimilitude. He argues that "the fact remains that this present is a time of memory and debt, of daily amnesia, uncertainty, and simulation. As such, we can no longer adequately describe our present-this moment of crisis of time-in the terms we have been using and developing" (204). ln the absolute, society erects statues and monuments to underline exemplary events or people whose actions highlight in a special way the foundational ethical values in the present. In the context at hand, the third historicity provides a way of looking at the present by identifying a new point of departure for historical inquiry and plotting for a new destiny. The Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga discourse inaugurates a less troublesome departure and foregrounds common intrinsic values that would steer the "memorialization" of past events, not for exalting purposes only, but for steering toward a new accommodating departure-what has been referred to as "le vivre ensemble" (living together).

The history of the Congo has oscillated between integrity preservation politics initiated by the Leopoldian regimen under The Act of the General Berlin Conference and identarian attractions often construed as ways out of economic woes for each region. Within this framework, presentism sustains a continuity discourse. Since Mobutu's demise, the identarian precedence that has regained prominence did not translate into sharp progress in Katanga, Kasai, or Bas-Congo. The public may have realized that secession proponents who rushed to claim their rights to go it alone stood in denial on the road that was traveled to the present masses over 85 years. ln a sense, nationalists such as Jason Sendwe (1917-1964), Lumumba, and-to some extent-Kasavubu (1910-1969) emphasized "presentism" as an unavoidable reality in response to the erection of a modern Congolese nation whose colonial yoke has been taken off. Mobutu's 32-year tight-fist modus operandi, a cascade of civil wars and hostilities exacted by a plethora of armed militias roaming in eastern Congo, triggered centrifugal tendencies to denounce this period by valorizing the local, the immediate, and the palpable. For example, at the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the DRC's independence fliers sponsored by the Katanga provincial administration displayed a series of important figures, including Tshombe dressed in his trademark tuxedo jacket known as "kateya". One thus witnesses the relevance of what Nora refers to as the "individualized memory" of the natives in re-imagining an area that was ideologically re-constructed and that resonated with a specific discursive claim: "Memory is blind to all but the group it binds [...] that memory is by nature multiple and yet specific; collective, plural, and yet individual" ("Between Memory and History" 9). However, the identarian politics need to be accommodated in order to negotiate a modus vivendi that may be crisis-free: the opposite of "bottom-up reconciliations" that Dibwe dia Mwembu ("Relectures de l'histoire" i0) is advocating. Thus, presentism offers an acceptable accommodation, albeit an imperfect one that may link up with what many analysts have suggested. lt generates not a perennial discourse based on nationalist ideas, but relies more on looking at past events with a renewed and less threatening mindset. lt is at this juncture that the notion and theory of continuity discourse becomes relevant to such a study defined as follows:

Narrative continuity draws on the past, defines today, and guides future actions by binding time and expressing moral judgment. Moral judgment is invoked to collectively manage issues by expressing shared beliefs and values. As a weapon against uncertainty, the logic of narrative continuity is this: By debating moral ideals, members of a community cocreate (constitute) the shared meaning and public interest they need to act normatively to achieve a functioning society. (Heath and Waymer 2)

The public is here confronted with the materiality of time in its phenomenological dimension coupled with the "topological conception of time" that brings to the surface painful memories of civil wars, ethnic cleansings, and especially the revival of costly social tensions. It brings into focus Michel Serres's conception of time in putting an iterative political and convenient relationship without its potential bluntness expected within the framework of historical linearity. The new disposition interrupts the semantic linearity of historical occurrences by rearranging elements to fittingly mimic idealistic pronouncements that have relevance in and with the immediacy of the present. The continuity discourse narrative is provisional, or at least it depends upon the status of formulated ideals. ln reality, the erection of the monuments translates in palpable terms the main ideas the power brokers want to convey. Sometimes, people go along with the continuity discourse; other times, they deviate from it because of compelling circumstances.

However, presentism is no advocacy for downgrading past events nor for dismissing potential occurrences. As Jeevan Vasagar writes, the ill-advised attempt to reinstall King Leopold II's statue in Kinshasa at the end of the Boulevard du 30 juin as an attempt to smoothen relations between the DRC and Belgium speaks volumes. After reinstalling the bearded king on horseback with fanfare, the statue was hastily removed the next day on authorities' order despite earlier comments by the then Minister of Culture Christophe Muzunge that the Congolese should be reminded of the colonial past so that it would not happen again. As a newspaper article notes:

Residents of Kinshasa could be forgiven for rubbing their eyes in disbelief. First, a statue of the late Belgian king Leopold II, whose rapacious colonial rule of Congo caused the death of millions of Africans, was reinstated in the heart of the Congolese capital. Then, less than a day later, it was gone again, mysteriously removed by the same workmen who had erected it. (Rannard and Webster)

This type of constraints of the present adequately explains the disappearance of the Belgian royalties' statues from the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga, especially at a time when even Belgium went into a serious soul-searching mode over the colonial era. The eventual removal was not only the consequence of the war against wrongly-honored colonial abusers, but a corrective political move that hardly had any viable future for ordinary people. The tide of interrogations of the celebratory moments of a dark epoch has known a worldwide appeal and a life of its own beyond political circles. Georgina Rannard and Eve Webster clearly and simply summarize the sentiments:

Widespread vandalism and defacing of the statues honoring King Leopold II across Belgian cities such as Antwerp, Ghent, Ostend and Brussels knew an upsurge, forcing authorities either to clean up or remove the statues altogether. This reminds of the widespread condemnation by other European colonial powers that crested in 1908 which prompted the passing of the Congo from the king's ownership to Belgium.

Heated debates raged in Belgium for several months and, according to The Brussels Times, petitions were circulated throughout the country asking the authorities to remove all the monarch's statues throughout the country. Various acts of vandalism pressured authorities to give in and allow the removal of statues (Chini n. p.). In this climate of denunciation and of deep skepticism for the Whiteman's Burden, it would have been highly ironic for Congolese authorities to have remained unfazed by this renewed indignation for sad events such as the "hands cutting" of the late 19th-century which was denounced worldwide.10 In fact, one should wonder why Belgian royalties were included in this political pantheon, even if the main goal was to celebrate the common history travelled by millions of Congolese for more than one century. As a matter of fact, "Les statues meurent aussi" (statues also die), to borrow the title of the 1953 documentary by Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Ghislain Cloquet, or they may be reminded to disappear, to change location, or even change complexion. The visit King Philippe and Queen Mathilde of Belgium paid the Congo from 7-13 June 2022 was hailed by both nations' local presses as a new era that attempts to re-orient the past towards smoother relations. In the Focus section of the 7 June 2022 Kinshasa newspaper Le Potentiel, one reads:

Cette première visite du neveu du Roi Baudouin sur le sol congolais depuis son investiture (2013), augure un nouveau départ après un climat tumultueux et glacial qui a régné entre les deux nations (RDC et Belgique). Bien plus, c'est une victoire n de la diplomatie régnante mise en place par le Président Félix Tshisekedi. Reste aux Congolais de capitaliser ce renouveau sans occulter les graves erreurs commises par la Belgique durant près d'un demi-siècle.

This first visit by King Baudouin's nephew on Congolese soil since his access to the throne (20i3) signals a new era after a cold and tumultuous climate that existed between the two nations (DRC and Belgium). In addition, it is a victory for the current diplomacy that President Félix Tshisekedi has engaged. It is now up to the Congolese to capitalize on this renewal without hiding the grave mistakes that Belgium committed for half a century.

In the Belgian daily Le Soir edition of the same day, Braeckman echoes the same sentiment of renewal by projecting King Philippe's visit as nothing but an indispensable restart for Belgium. The remains of Lumumba will soon be returned by Belgium to the Congo for burial in Kinshasa on the boulevard bearing his name.

Conclusion: The life of statues

The fact that statues can 'die' also means that they can take a different dimension from the original design through appropriation dictated by the needs of the moment. Pragmatism allows the prospects of finding and adopting a unifying discourse and even urges the use of meta-discourses that promote national ideals. These include a re-imagined repositioning or attitude by major figures vis-à-vis their deeds, decisions, or words. Remembering them therefore takes a new turn by reliving undesirable actions with strongly choreographed movements for newer, better, and sound demeanors. As Hartog reminds us, strategic amnesia can paradoxically be timely. The display at the Gouvernorat du Haut-Katanga does not involve the iteration of events, however pertinent and important, but the fleshing out of what Nora (Présent, nation, mémoire 9) refers to as "le récit de la collectivité nationale" (the narrative of national collectivity). The display comes out as a tapestry that brings several discursive strands into a framework where the national and the provincial strings coexist, interact, and do not neutralize each other. Unlike the process of memory, brutalities inflicted are not "open to the dialectic of remembering and forgetting", but rather to mitigation, including the imagined realignment of political figures in their symbolic relevance. This act of reconstructing is "not in the realm of memory", but certainly part of Congolese history in all its ramifications fostered by once heightened brutalities and claims of separation. We lean more on the side of Geschichte rather than Historie, as the Germans would put it. They participate in Historie by lending themselves to the reconstruction of positions as highlighted by new imagined postures that articulate ambient values. The aim is not to suppress or to annihilate anything, but to reinforce underlying unifying values. lt is safe to maintain that the primary function of these monuments is not "anchoring memory" of illustrious personalities, but to stress their symbolic value in celebrating a discourse of unity with a strong relational framework. That is where the durability of virtue would prevail. History has allowed doubt about earlier projects-secession or ethnic cleansing-to set in. History has the upper hand over memory-Thistoire aura le pas sur la mémoire" (Nora, Présent 22). A close look shows that it is a matter of validating the co-existence of opposites, but recognizes both frames of reference as complementary rather than oppositional.

This goes far beyond "realpolitik" and launches the consolidation of group identity, whether national or provincial. When well executed, it is a liberating stance that substantially relaxes ideological and ethno-nationalist manacles (Nora, Présent 23). As such, the score of statues have the value of a text with a pedagogical intent that history would link to contested memories of diverse events within a framework of acceptability. This can be illustrated by the recent events in Virginia, USA, where the removal of the i2-ton and 2i-foot bronze Robert E. Lee statue was the city's big event on 3 September 202i. This was the culmination of an earlier order to take down the statue as a symbol of hate from Governor Ralph Northam (2018-2022), a decision taken only two weeks after George Floyd's death. When the Virginia Supreme Court cleared the last legal obstacle, it unceremoniously came down.11 Three weeks after the fall of the "Lee Statue" on Monument Avenue, the newest monument, the "Emancipation and Freedom Monument" representing a freed slave, was inaugurated on Brown's Island. This one reflects the representational dynamics that in less than a year swept aside the whole sleuth of heavy Confederate Monuments and ushered, as Michael Paul Williams of the local paper Richmond Time Dispatch summarizes in the title of his editorial, "from a city that elaborately lauds oppression to one that celebrates freedom".

Notes

1 There were African slaves brought by Spaniards to Florida at an earlier date than 1609, almost one century before (1525-1530). The tour and the museum at the Jamestown Settlement include an exposé on Angela, a set of explanations on her existence, and on ongoing excavations to find evidence of her life in Captain William Pierce's household. She is cited in two census instances as living in this household, most likely as a housemaid. The inscriptions at the top of the sketch representing her reading "Against their will" are notable.

2 For more details, see Ludo de Witte's De Moord op Lumumba translated from the Dutch as Assassination of Patrice Lumumba, 2001. Other similar narratives have appeared since then.

3 All translations from French are my own.

4 Each trend, including the Katangan identity as a non-fixed notion, is shaped by all kinds of rearrangements by politicians, along ethnic lines (Sempya, Lwanzo Lwa Mikuba, and territorial associations, whether between Katangese themselves or in relation to other non-Katangese nationals). Other former big provinces such as le Grand Kasai or le Grand Kivu, know similar readjustments.

5 According to Patrice Mufuta Kabemba (ii9), a kasàlà is a praise poem in free verse stringing together praise names. It is sung or recited on a high note in open spaces where people gather.

6 Of note is Claudy Khan's well-known painting "Les Larmes de Beni" (Khan), a copy of which President Félix Tshisekedi offered to Pope Francis on his visit to the Vatican in January 2020.

7 This is essentially to follow the conclusion ofthe Congo Mapping, an UN-sanctioned investigation on the brutalities in eastern Congo that strongly suggested that such a court be established.

8 The interview by Dominique Munongo Inamwizi, daughter of Katangese secessionist Interior Minister Godefroid Munongo (1925-1992), has been to date the most vocal incendiary idea by a National Representative. Prime Minister Jean-Michel Soma Lukonda, himself a Katangese, preaches peaceful coexistence (see Bomboka).

9 The pairing of Lumumba and Kabila as national heroes has been enshrined by the creation of L'Ordre national héros nationaux Kabila-Lumumba awarded to illustrious individuals such as Father Léon de Saint Moulin in 2019.

10 Edmund Morel (1873-1924) and Roger Casement (1864-1916) founded the Congo Reform Association that launched an international protest against King Leopold's iron-fist trade in ivory and rubber that made a fortune for some individuals and caused misery for the natives.

11 After almost an i8-month battle that divided the Richmond community, the local newspaper Richmond-Times Dispatch's headline read "'This statue represents division:' The nation's largest Confederate statue no longer stands on Monument Avenue" by Chris Suarez, Mel Leonor, and Sabrina Moreno. The article captures the urgency with which a sizeable part of the nation needed to look at the present times with a critical mindset to forge a new future.

Works Cited

Africa Research Bulletin. "DR Congo-Belgium: Colonial Regrets." Africa Research Bulletin vol. 57, no. 6, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-825X.2020.09544.x. [ Links ]

Bayart, Jean-François. "Fin de partie au sud du Sahara." La France et l'Afrique: Vade mecum pour un nouveau voyage, edited by Serge Michailof. Karthala, 1993, pp. 485-510. [ Links ]

Bomboka, Patrick. "RDC: Sama Lukonde prêche la cohabitation pacifique entre katangais et kasaïens à Lubumbashi." Zoomeco. 24 Apr. 2022. https://zoom-eco.net/a-la-une/rdc-sama-lukonde-preche-la-cohabitation-pacifique-entre-katan-gais-et-kasaiens-a-lubumbashi/. [ Links ]

Braeckman, Collette. "Visite royale: l''indispensable' visite du Roi au Congo." Le Soir. 7 Jun. 2022. https://www.lesoir.be/446730/article/2022-06-06/visite-royale-lindis-pensable-visite-du-roi-au-congo. [ Links ]

Chini, Maïthé. "Petition launched to remove all statues of Leopold II in Brussels." The Brussels Times. 20 Jun. 2020. https://www.brusselstimes.com/brussels/ii47i3/petition-launched-to-remove-statue-of-leopold-ii-in-brussels. [ Links ]

Demetriou, Dan & Ajume Wingo. "The Ethics of Racist Monuments." The Palgrave Handbook of Philosophy and Public Policy, edited by David Boonin. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, pp. 341-55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93907-0_27. [ Links ]

Deutsche Welle. "Belgium: King Leopold II statue removed in Antwerp after anti-racism protests." Deutsche Welle. 6 Sep. 2020. https://www.dw.com/en/belgium-king-leo-pold-ii-statue-removed-in-antwerp-after-anti-racism-protests/a-53755021. [ Links ]

Dibwe dia Mwembu, Donatien. "La réharmonisation des rapports entre les Katangais et les Kasaiens dans la province du Katanga (i99i-2005)." Anthropologie et sociétés vol. 30, no. 1, 2006, pp. 117-34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/013831ar. [ Links ]

__________________. "Relectures de l'histoire et transformation des rapports entre les Katangais et les Kasaiens du Katanga." Vivre Ensemble au Katanga, edited by Donatien Dibwe dia Mwembu & M. Ngandu Mutombo. L'Harmattan, 2005. pp. 15-178. [ Links ]

__________________. "L'épuration ethnique au Katanga et éthique du redressement des torts du passé." Canadian Journal of African Studies vol. 33, no. 2-3, 1999, pp. 483-99. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.1999.10751170. [ Links ]

Gobbers, Erik. "Katanga: Congo's Perpetual Trouble Spot." Egmont Royal Institute for International Relations, 2016, pp. 1-6. http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep06553. [ Links ]

Gorus, Jan. "Ethnic violence in Katanga." Conflict and Ethnicity in Central Africa, edited by Didier Goyvaerts. Institute of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa & Tokyo U of Foreign Studies, 2000, pp. 105-26. [ Links ]

Gras, Romain. "RDC: le Katanga, pris en tenaille entre Kabila et Tshisekedi." Jeune Afrique. 5 May 2021. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1159558/politique/rdc-le-katan-ga-pris-en-tenaille-entre-kabila-et-tshisekedi/. [ Links ]

Hartog. François. Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and the Experiences of Time. Columbia U P, 2015. [ Links ]

Heath, Robert L. & Damion Waymer. "Public Relations Intersections: Statues, Monuments, and Narrative Continuity." Public Relations Review vol. 45, no. 5, 2019, pp. 1-10. DOl: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.03.003. [ Links ]

Hoffmann, Stefan-Ludwig. "François Hartog. Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and Experiences of Time." The American Historical Review vol. 121, no. 2, 2016, pp. 535-6. DOl: https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/121.2.535. [ Links ]

Kabemba, Patrice Mufuta. Le Chant Kasàlà des Lubà. Armand Colin, 1969. [ Links ]

Pongo, Martin Kalulambi. "Dreams, Battles, and the Rout of the Elite in Congo-Kinshasa: The Mourning of an lmagined Democracy." Issue: A Journal of Opinion vol. 26, no. 1, 1998, pp. 22-6. DOl: https://doi.org/10.2307/1166548. [ Links ]

Kapanga, Kasongo Mulenda. The Writing of the Nation: Expressing Identity through Congolese Literary Texts and Films. African World P, 2017. [ Links ]

Khan, Claudy. "Les Larmes de Beni." Migoo. https://migoo.org/pgi=detail-produit-MjM5. [ Links ]

Le Potentiel. "Visite du couple royal: Kinshasa-Bruxelles-nous revoici." Le Potentiel. 7 Jun. 2022. https://lepotentiel.cd/2022/06/07/visite-du-couple-royal-kinshasa-bruxelles-nous-revoici/. [ Links ]

McGregor, Andrew. "New Offensive Expected Against Mai Mai Militias in Mineral-Rich Katanga." Jamestown Foundation. 4 Apr. 2014. www.refworld.org/docid/534f99be4.html. [ Links ]

Nora, Pierre. "Between Memory and History: Les Lieux De Mémoire." Representations no. 26, 1989, pp. 7-24. DOl: https://doi.org/10.2307/2928520. [ Links ]

__________________. "La loi de la mémoire." Le Débat no. 78, 1994, pp. 178-82. DOl: https://doi.org/10.3917/deba.078.0178. [ Links ]

__________________. Les lieux de mémoire. Gallimard, 1984. [ Links ]

__________________. Présent, nation, mémoire. Gallimard, 2011. [ Links ]

Radio Okapi. "Cinquantenaire: inauguration des monuments de Kasavubu et Tshombe. [ Links ]"

Radio Okapi. 29 Jun. 2010. https://www.radiookapi.net/actualite/2010/06/29/cinquantenaire-inauguration-des-monuments-de-kasavubu-et-tshombe. [ Links ]

__________________. "RDC: A Bukavu, l'artiste musicien Dadju s'engage à lutter contre les violences sexuelles faites aux femmes." Radio Okapi. 29 Jun. 202i. https://www.radiookapi.net/2021/06/29/actualite/culture/rdc-bukavu-lartiste-musicien-dadju-sengage-lutter-contre-les-violences. [ Links ]

Rannard, Georgina & Eve Webster. "Leopold Il: Belgium 'Wakes up' to its Bloody Colonial Past." BBC News. 13 Jun. 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53017188. [ Links ]

Savage, Kirk. Monument Wars: Washington, D. C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape. California U P, 2009. [ Links ]

Vasagar, Jeevan. "Leopold reigns for a day in Kinshasa." The Guardian. 4 Feb. 2005. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/feb/04/congo.jeevanvasagar. [ Links ]

Vinckel, Sandrine. "Violence and everyday interactions between Katangese and Kasaians: Memory and elections in two Katanga cities." Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, vol. 85, no. 1, 2015, pp. 78-102. www.jstor.org/stable/24525606. [ Links ]

Williams, Michael Paul. "Richmond 'If we live up to it.' Richmond's Newest Monument Celebrates Freedom, Not Oppression." Richmond Times-Dispatch. 24 Sep. 2021. https://richmond.com/zzstyling/column/williams-if-we-live-up-to-it-richmonds-newest-monument-celebrates-freedom-not-oppression/article_85373e3d-caef-53ae-8b90-fb9e4fe94a56.html. [ Links ]

Willig, Carla. "Discourse Analysis." The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, edited by Jonathan A. Smith. Sage, 2015, pp. 143-67. [ Links ]

Zeleza, Paul Tiyambe. "The Original Sin: Slavery, America and the Modern World." USIU Africa. Aug. 20i9. http://erepo.usiu.ac.ke/11732/5782. [ Links ]

Submitted: 11 October 2021

Accepted: 10 May 2022

Published online: 18 September 2022