Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Tydskrif vir Letterkunde

On-line version ISSN 2309-9070

Print version ISSN 0041-476X

Tydskr. letterkd. vol.59 n.1 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/tl.v59i1.8842

REVIEW ARTICLES

The Garment Workers' Union Pageant of Unity (1940) as manifestation of transnational working-class culture

Matgorzata Drwal

Assistant professor in the Department of Dutch and South African Studies, Faculty of English, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland, and a research fellow in the Department of Afrikaans, Faculty of Humanities, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. Email: maldrw@amu.edu.pl

ABSTRACT

In this article, I examine the Garment Workers' Union's theatre as a manifestation of transnational working-class culture in the 1940s. Analysing Pageant of Unity (1940), a play in which Afrikaans and English alternate to express the equality of Afrikaans- and English-speaking workers in the face of exploitation, I offer an attempt to escape the confines of a national literature as linked to a single language. I demonstrate how the political pageant-a genre typical of socialist propaganda and international trade unionism-was adapted to a South African context. This drama is, therefore, viewed as a product of cultural mobility between Europe, the United States, and South Africa. Assuming the 'follow the actor' approach of Bruno Latour's Actor-Network Theory, I identify a network of interconnections between the nodes formed by human (drama practitioners and theoreticians, socialist organisers) and nonhuman actors (texts representing socialist drama conventions, in particular agitprop techniques). Tracing the inspirations and adaptations of conventions, I argue that Pageant of Unity most evidently realises the prescriptions outlined by the Russian drama theoretician Vsevolod Meyerhold whose approach influenced Guy Routh, one of the pageant's creators. Thus, I focus on how this propaganda production utilises certain features of the Soviet avant-garde theatre, which testifies to the transnational character of South African working-class culture.

Keywords: working-class literature, political pageant, avant-garde theatre, propaganda, Garment Workers' Union, transnational working-class culture, cultural mobility.

Introduction

Among the documents held in the Garment Workers' Union (GWU) archives at the William Cullen Library of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, there is a 16 page long bilingual brochure promoting an event called Trade Union Rally and Pageant for a Living Wage / Vakunie Optog en Skouspel vir 'n Beter Lewe, which took place on 22 February 1940 at Johannesburg City Hall. The booklet, printed to be distributed among the workers, states that the rally is "an event of outstanding importance in the Trade Union Movement in South Africa [...] [that reflects] the rising discontent of the working people with the whole system of industrial legislation" (Trade Union Rally 10). The brochure contains photographs and information about the leading GWU activists and an appeal by the union's secretary Solly Sachs in English and in Afrikaans entitled "We Declare War on Starvation Wages"/"Ons verklaar oorlog teen hongerlone". Sachs urges all workers and unemployed people to unite their ranks: "by mass campaigns organized on an unprecedented scale, we shall awaken the masses of starving people from their long sleep" (Sachs 2). He emphasises the international and interracial ideal of trade unionism, calling to oppose "all those Fascists and Reactionaries who have been misleading the masses of workers by means of poisonous racial propaganda" (2). The event that he invites them to take part in promises "a kaleidoscopic programme of entertaining and thought-provoking items" (10). These include speeches by the union's leading activists, such as Johanna Cornelius, Dulcie Hartwell, and Anna Scheepers, among others; communal singing and recitation; and Pageant of Unity (A Working-Class Pageant). The booklet contains lyrics of the songs in English or/and in Afrikaans to be sung during the pageant and provides a short explanation of its message in both these languages. The script of this working-class drama can also be found in the same file in the archive.1

The concept of working-class literature has historically been ambiguous and remains problematic. It can be defined by an author's or intended reader's class background, but also by a text's function as a document of working-class experience or as a carrier of a proletarian message (Nilsson and Lennon, "Defining Working-Class Literature(s): A Comparative Approach Between U.S. Working-Class Studies and Swedish Literary History" 43). Considering the diversity of definitions, I argue that the most distinct quality that describes working-class literature is its belonging to a counterculture and its invention of "its own means of expression in opposition to the petit-bourgeois art" (Foley 140). Activities such as publishing newspapers, organising meetings, and social events possess a "humanising" (138) aspect. They shape a political community, allowing "the collective of alienated workers to create a new, modern egalitarian socialist culture" which gives "dignity in an oppressive system" (138-9). Furthermore, as Nilsson and Lennon observe, too often working-class literature tends to be situated within the confines of national literatures, despite the internationalism that was supposed to characterise labour and socialist movements ("Introduction" xii). They also draw attention to the lack of modern comprehensive scholarship that involves looking for interconnections, inspirations, and similarities between the forms and artistic means of working-class art that are employed in different contexts (xi).2

I propose that the literature created by and for South African white workers in the 1930s and 1940s was a manifestation of transnational working-class culture. I argue, therefore, that Pageant of Unity, staged by the GWU, was a product of cultural mobility. Cultural mobility is understood as a process of circulation across national and cultural borders in which "texts, images, artifacts, and ideas are moved, disguised, translated, transformed, adapted, and reimagined" (Greenblatt 4). Greenblatt (250-1) suggests that when tracing cultural mobility the point of departure should be an assumption that all physical movement of people and objects involves also metaphorical movement: circulation of concepts between the centre and periphery resulting in modifications, distortions, and appropriations. He also encourages looking into contact zones where cultural exchange takes place, and identifying people, institutions, and other factors that facilitate or hinder it (251). Because its central premise is the idea of contact and exchange, this approach offers a suitable tool to describe working-class culture. It corresponds with the labour movement's programmatic call to unite over national divides in an attempt to create a transnational community of workers.

In this paper, I view working-class culture as a contact zone in which the transfer of certain drama conventions from the Soviet Union to South Africa took place. I focus on how South African activists, socialist playwrights, and rank-and-file workers interacted with workers' culture elsewhere, in this way realising the ideal of socialist internationalism. Taking the "follow the actor" (Latour 12) approach, I set out to map a network of connections consisting of both human (playwrights, activists) and nonhuman (texts, dramatic conventions, genres) nodes, which will allow me to position the GWU's creativity within the frameworks of transnational workers' culture.

Texts and genres are particular kinds of actors: they are mediators in the network. They allow other actors to connect, but also "transform, translate, distort, and modify the meaning or the elements they are supposed to carry" (Latour 39). The transfer of socialist drama conventions to South Africa involves translation, which is here understood not in the literal sense as a linguistic transposition, but as "the countless mediations that bind together human and nonhuman actors" (Felski 751). Translation is, therefore, the key metaphor to indicate "the means by which paths are connected, actions are coordinated, and meanings are transmitted" (752). The network and translations that it involves will emerge from my discussion of the sources of the dramatic genres, their modifications, and agents responsible for their transfer to South Africa. Eventually, I will account for the ways in which the transnational model of socialist propaganda was adapted to the local South African background.

The discussion opens with an overview of the research on the cultural products of the GWU, in particular its theatre. This is followed by an outline of the origins of the key working-class dramatic genres: the pageant and the agitprop (agitation propaganda) play, which can be traced to the Soviet Union and the United States. I go on to present a network of human actors involved in the transfer of the genres to South Africa. Then I elaborate on the ways in which the pageant format was applied within nationalist and internationalist frameworks. Afterwards, I focus on the script of Pageant of Unity, presenting its structure and characters, emphasising how it employed the dramatic conventions that were transferred from the international context to the South African one and thus adapted accordingly.

The Garment Workers' Union culture

South Africa's rapid modernisation in the first half of the twentieth century played out in the wake of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). While this military conflict resulted in the impoverishment of the countryside, cities, with their booming industry, attracted masses of the white rural population, leading to the formation of the white working class and trade unionism (Berger, Threads of Solidarity: Women in South African Industry, 1900-1980 90). The GWU was an organisation consisting of mainly Afrikaner working-class women and was established in Johannesburg in 1930 on the initiative of Emil Solomon (Solly) Sachs, an experienced socialist organiser. Shortly afterwards it set up branches in other industrial centres, such as Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. During World War II, many women of colour entered the clothing industry, which had an impact on the union's structure. In 1940, a separate branch, no. 2, was created for these women, even though the organisation officially maintained a non-racial policy (Berger, "Solidarity Fragmented: Garment Workers of the Transvaal, 1930-1960" 136). Petitioning and organising strikes, the GWU strove to improve working conditions and wages. It also contributed to the creation of a distinct white working-class culture. Apart from providing the newly formed white proletariat with entertainment, the union conducted an awareness-raising campaign by means of art and literature, which was tailored to the needs and sensibility of the working-class public.

The existing body of research on the garment workers' theatre is meagre. Scholars have focused on the economic background against which the Afrikaans-speaking workers' theatre emerged and only briefly pointed to the implications of this theatre for the development of Afrikaans literature (Willemse 10). In her groundbreaking research, Brink provided the first discussions of the garment workers' cultural activities, which encompassed drama, as well as poetry and prose. She stressed that this overtly didactic literature served to create a new female identity for white working-class women, "Voortrekker women of the new urban, industrial environment" (Brink, "Purposeful Plays, Prose and Poems: The Writings of the Garment Workers" 125). Referring to the Voortrekker political mythology, these women workers "staked the claim to the same cultural heritage" (Brink, "Plays, Poetry and Production: The Literature of the Garment Workers" 34) as Afrikaner nationalists. In his overview of the plays, Coetser argues that the GWU theatre formed an alternative Afrikaans theatre, operating outside of the mainstream of Afrikaans drama in the 1930s and 1940s (73). He also observes that the playwrights, such as Johanna and Hester Cornelius, incorporated autobiographical elements in their dramas, in this way documenting the history of their class (65-6). Moreover, such drama practitioners emerged spontaneously from the ranks of the union, without any mediation by external cultural workers (72). This last observation is, however, true only when considering scripts drawn up later than the second half of 1941, when the GWU established its Unity Theatre (Cornelius, "Eendrag teater" 11). The first dramas in which the garment workers performed as part of their propaganda activities, were, in fact, created by authors who were not garment workers themselves. Pageant of Unity is an example of such a play, not written by a GWU member. Rather, its authors, Eli Weinberg and Guy Routh, were associated with the South African Communist Party and black trade unionism. Their links with the communist movement and, consequently, with Soviet art, encourage looking at South African workers' theatre as part of a wider network and for its transnational connections.

Brink observes that the garment workers had "great admiration for all things Russian" ("Purposeful Plays" 123) and were in particular concerned with the plight of Russian women and children during World War II. She does not, however, elaborate further on the ways in which this fascination manifested itself in GWU cultural and creative products. One such form of inspiration is the presence of socialist realism in the plays created by GWU playwrights (Drwal 5). This artistic convention, which during the Soviet Writers Congress in 1934 was declared the national literary method in the Soviet Union, offered a way of reconciling the internationalist message with a local, in particular rural, setting (Tagangaeva 340). It included the narodnost principle, i.e., the reliance on a folkloristic element to convey a socialist message as familiar and compatible with local culture. An example of the application of this principle in GWU dramas can be found in the play Die Offerande (The Sacrifice) (1941), in which Afrikaner farmers-turned-workers are called upon to unite and fight against the oppressing English capitalist (Drwal 6-10). Another example of inspiration and borrowing can be observed in the use of such propagandistic genres as the working-class pageant and the agitprop drama. This is the focus of this article.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the pageant format in South Africa mostly served to illustrate the progress of European/Europeanised civilisation on the African continent (Kruger, The Drama of South Africa 23-9). As Kruger observes, black South Africans employed the genre to convey the New African modernity, Afrikaners- to propagate the idea of a white South African nation (33-6). The fact that the form was also used by white workers in an attempt to introduce working-class internationalism to South Africa seems to be an unrecognised cultural phenomenon. Since there is no research conceiving of the GWU drama as part of the pageant tradition, this article is aimed at addressing this issue.

The pageant-origins and adaptations

Mapping a transnational network within which I position Pageant of Unity, my point of departure is a nonhuman actor: the pageant format. Due to its role as a mediator, it allows for a translation of a variety of messages into a visual form, but "input is never a good predictor of [its] output" (Latour 39), i.e., the message can undergo all kinds of transformations resulting in various artistic products. Moreover, it accounts for a chain of connections between such actors as professional and amateur playwrights, religious practitioners, citizens displaying their patriotism, social and political activists, and workers.

The origins of the pageant tradition go back to the medieval mystery play. Due to its performative character, the pageant conveyed a spiritual message in a way that was comprehensible to illiterate audiences. Characteristic was the use of tableaux vivant (living pictures), allegorical scenes in which the players used pantomime or stood motionless to illustrate the message (Hummelen 200). Medieval pageants were part of a religious ritual that invited the audience's participation, in particular when they involved a procession, like those held to celebrate the Eucharist on Corpus Christi Day (Bell 54). In the course of time, the pageant expanded beyond the sphere of religious practices. As a spectacle where the boundary between the actors and the audience is blurred, it was well suited to bringing all kinds of communities together. Consequently, it turned out equally appropriate for the ludic carnival celebrations, propagation of patriotic feelings binding national communities, and working-class protest against exploitation.

The pageant as a spectacle explicating civilization's advancement and reinforcing a national agenda was particularly popular in North America in the early 20th century. The American Pageant Movement, offering entertainment and instruction, extolled the nation's progress throughout history and promoted patriotism and community values (Fishbein 197, 217). Similar to the American Pageant Movement's patriotic dramas were South African pageants of 1910, 1936, and 1938. All of them were prepared to accompany celebrations of an important political event and functioned as a ritual, appealing to the emotions of the masses and perpetuating a certain vision of history. Blurring the boundary between the performers and spectators, "the concept of a pageant-performance epitomizes imperial and national identity-formation" (Merrington 5). Through its symbolic and ritualistic character, the pageant sought to "impl[y] continuity with the past" (Hobsbawm 1) and thus served the invention of tradition.

The Pageant of Union (or The Pageant of South Africa) was staged in 1910 in Cape Town and accompanied the inauguration of the newly formed State, the Union of South Africa. The drama presented the history of the European conquest of South Africa "interpreted as a racial-evolutionary sequence that ran through degrees of supposed 'barbarism' to 'civilization', with the English as the apogee of this scale of humankind" (Merrington 9). It emphasised, however, that the Dutch and the English seamlessly merged, creating a union and a truly civilised state in South Africa and thus reinforced "a putative national and racial identity" (5). The plot depicted the black people of Africa as ahistorical background characters, glossing over the industrialisation and progressing proletarianisation of African peasants working in the mines (Kruger, The Drama 22). The play, featuring amateur performers, was directed by Frank Lascelles, a British pageant master, who produced a number of pageants which were staged throughout the British Empire. These imperial pageants followed the same formula: they were open-air spectacles, stretching over two or three days, comprising chronologically arranged historical episodes with minimal dialogue, and were concluded with a dramatic epilogue or masque (Merrington 6). Keuris notes the use of the tableau vivant as part of such performance. She points out that this convention was familiar to the early Afrikaans theatre since the late 19th century and its roots can be traced to European, especially Dutch models (Keuris 748). On numerous occasions, most notably in the pageant of 1910 and the Great Trek Centenary celebrations in 1938, the tableau vivant served to accentuate the nationalist message (750).

In 1936, another Pageant of Southern Africa was prepared, which in turn was "intended to address the differences between Anglo and Afrikaner interpretations of history as well as to reinforce their commonalities" (Kruger, The Drama 33). This drama, together with the Empire Exhibition, was designed to celebrate the Johannesburg Golden Jubilee (1886-1936) and to honour "Africa's most modern city" (23). The text of the play was written by Gustav Preller, who had significantly contributed to the Afrikaner nationalist mythology by his evocative account of the Voortrekkers' history in his 1918-1938 book series Voortrekkermense (Voortrekker People) and in the film De Voortrekkers (1916). Executed under the direction of the Belgian-born André van Gyseghem, this pageant bore similarities with the spectacle of 1910. This time, too, it painted a glorious history of progress from a colonial perspective, underlining the significance of the creation of the Union of South Africa, additionally incorporating the themes of industrialisation and modernisation.

Yet the greatest in scale was the pageant of 1938 that marked the centenary of the Boers' resistance against the British resulting in the Great Trek and the vow they took at the Battle of Blood River in 1838. The re-enactment of the Great Trek involved nine ox-wagons travelling from Cape Town to Pretoria, with many points along the route where people gathered to celebrate, and a culmination in Pretoria on 16 December, when the cornerstone was laid for the Voortrekkermonument, "the altar of Afrikanerdom" (Kruger, The Drama 37). The celebrations included speeches by the National Party leaders, folk dance and song, prayers, a screening of the film Die bou van 'n nasie (The building of a nation) whose script was written by Preller, and the allegorical drama of national loss and recovery Die dieper reg (The deeper right) written by the poet N. P. van Wyk Louw and directed by Anna Neethling-Pohl, known for her nationalist views (39).

Notably, garment workers also organised their "kappiekommando" (bonnet commando) to join the celebrations, which led to their being criticised by the nationalists and to a polemic in the Klerewerker/Garment Worker magazine (Cornelius, "Ons en die voortrekker-eeufees" 4; Anon., "Aan 'Die Transvaler'" 5). While the garment workers wanted to emphasise their being Afrikaner volksmoeders (patriotic mothers of the nation) and their identification with the history of the pioneers, nationalist commentators accused them of interracial solidarity under the banner of alien communism.

Workers' theatre

The South African nationalist pageants, however, were not the source of inspiration for the GWU pageant. The most probable model seems to be the Soviet workers' pageant that flourished in the 1920s and served to propagate the spirit of the revolution (Bell 56). But even before, the format emerged in the United States, where the Paterson Pageant of 1913 marked the beginning of a new approach to the political drama.

The workers' pageant offered a dramatic shift in the traditional pageant that tended to emphasise the "divine elements in the historical events it chose to dramatize" (Fishbein 218). The Paterson Pageant, whose script was written by the journalist John Reed, was a collaboration between New York radical intellectuals and Paterson silk workers. It involved a re-enactment of a current strike and aimed to draw the attention of the middle-class audience to the workers' plight. Unlike traditional American pageants that recreated a glorious past event and served to solidify the status quo, the workers' pageants depicted and documented contemporary events, thus becoming documentary dramas (Dawson 68). Most importantly, they questioned the current state of affairs and dramatized the class struggle in an attempt to bring about social change (Fishbein 213). An important element of these pageants was a song jointly sung by the actors and the audience. Singing was supposed to appeal to the worker "emotionally and intellectually" (221) and to reinforce the feeling of sharing the goal of class struggle. The repertoire included folk songs and labour movement classics, such as "The Marseillaise", "The Internationale", and "The Red Flag", as well as songs composed specially for the occasion of the performance (205-6).

It is likely that Reed's pageant influenced the Russian Nikolai Evreinov to create Storming of the Winter Palace (1920), a mass outdoor spectacle, documenting the October Revolution and featuring eight thousand soldiers and sailors (Dawson 66). As a popular propaganda tool, many similar re-enactments of the revolution took place in the Soviet Union between 1918 and 1922 with an aim of providing the audience with the experience of having participated in the revolutionary events (66).

Another form of documentary drama that was common after the 1917 October Revolution in the Soviet Union and that also had its counterpart in the United States was the living newspaper (zhivaya gazeta). This particular kind of agitprop drama was meant as an easily comprehensible presentation of newspaper news on stage by actors holding posters, forming tableaux vivant, using monologue or dialogue, declamation, sketches, and songs (20). The form was initially practiced by the Blue Blouse, the first regular agitprop troupe, which was set up in 1923 in Moscow (76). Similar troupes, however, operated among workers' theatre movements in Germany (Dawson 19; Altenbaugh 198) and during the crisis years of the 1930s in the United States, where the New Theatre League prepared dramas addressing problems relating to workers' struggle and social injustice (Altenbaugh 197). Agitprop dramas were one-act satirical plays put on during strikes in public spaces or at union meetings.

They used chanted dialogue and "movement in which the actors, performing in unison, symbolized the working-class solidarity necessary for the overthrow of the bosses" (Goldstein 32). The agitprop drama employed easily recognisable symbols and devices, which it shared with expressionistic theatre, which was flourishing at the same time (Altenbaugh 198). Moreover, the amateur agitprop theatre had a far-reaching impact on professional playwrights such as Meyerhold, Brecht, and Piscator (Illustrated Encyclopedia of World Theatre 12).

Tracing the spread of the pageant and the agitprop drama as mediators in the network allows me to identify human actors whose contact they made possible. Kruger (Post-Imperial Brecht 220) underscores the impact of the Russian Vsevolod Meyerhold's avant-garde theatre on the South African workers' theatre creators, including on Van Gyseghem and on Routh, one of the authors of the garment workers' Pageant of Unity. Moreover, she points to similarities between Meyerhold's and Brecht's approaches, with both bearing an "imprint of internationalist socialist culture that informed proletarian theatre in the 1920s and 1930s, from Germany, the Soviet Union, the United States and Japan" (220-1). Kruger observes that this internationalism "influenced worker-players in South Africa, from the Afrikaner working-class women in the Garment Workers' Union to the mostly African male white-collar workers (teachers and clerks) of the Bantu People's Theatre" (221). They all used similar forms of expression and, like Brecht's experimental Lehrstücke, aimed to instruct the audience members by transforming them into active participants in the play rather than treating them as mere spectators.

Interestingly, Van Gyseghem, employed as the pageant master for the spectacle of 1936 that praised the imperial rule in South Africa, later became the director of the Bantu People's Theatre, a South African variant of a British Unity Theatre, staging socialist dramas (Sandwith 302). Van Gyseghem had gained experience in the Soviet Union and in the United States where he produced the living newspapers and documentary plays about current events (Kruger, The Drama 221). Thus, on his arrival in South Africa, he introduced some of the modernist drama techniques to both nationalist and socialist dramas. Van Gyseghem's successor as the director of the Bantu People Theatre, Routh, shared these inspirations (Sandwith 302).

Pageant of Unity as avant-garde drama

Engaging workers' emotions and intellect, the drama served socialist organisations and trade unions as an effective propaganda tool. The Unity Theatre, which was established by the GWU in 1941, was modelled on Unity Theatres that had already operated in Britain (in such industrial cities as Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow, and London) and in the United States (e.g., the Theatre Union in New York). In South Africa, too, similar institutions for black workers had already been run by South African socialist intellectuals (Kruger, The Drama 75). Thus, the GWU employed the same forms and devices that had been used by trade unions' cultural sections in Europe, in the United States, and elsewhere in South Africa. In this respect Routh's role as the agent in the transfer of these forms needs to be noted.

As its brochure informs, Pageant of Unity was written by Weinberg and Routh. Both authors were trade unionists and members of the multiracial Communist Party. Their previous experience included creating art addressed to, and having as its subject matter, the lives of black workers. Thus, through their involvement in the GWU drama, they became a link between the black and white workers' cultures. Weinberg (1908-1981) was asked by Sachs to set up the GWU's branch in the Western Cape. He was also active as a photographer documenting working-class life (Verwey 264). The brochure introduces him as the producer of the drama, and the organiser of a rally in Port Elizabeth that was "attended by thousands of workers" (Trade Union Rally 10) and which gained a lot of publicity.

Routh (1913-1993) is introduced as the current director of the Bantu Peoples' Theatre with "varied dramatic experience", author of many songs, and a couple of plays (Trade Union Rally 11). According to Kruger (The Drama 71), Routh wrote such political dramas as The Word and the Act and Patriot's Pie, which conveyed a reaction to current events in South Africa and illustrated the plight of the African township population. Routh believed that the theatre could contribute to "the forging of a more inclusive and more accessible national cultural practice in South Africa" (Sandwith 302). In the 1930s, he was involved in the creation of an experimental theatre in Johannesburg. Influenced by Meyerhold's innovative approach to drama, including "biomechanical acting and constructivist staging" (Routh 26), Routh tried to apply the aesthetics of modernity in the South African context. He proposed a theatre that aims to reveal the mechanisms behind socio-political forces of oppression and guides the audience to political enlightenment that can lead to "real social change" (Sandwith 303).

Meyerhold saw theatre as a mass spectacle, comparable to a sporting event watched by a crowd at a stadium (Meyerhold 256). He advocated an aesthetic subjugated to modern social conditions, with a concept of utilitarian beauty, claiming that "the art of today is different from the art of a feudal or bourgeois society" (270). He also emphasised that the play is only created while being performed together by the actor and the spectator, and that the director merely provides rough guidelines (256). To ensure the drama's message is clearly and unambiguously conveyed, the spectators must be directly informed-e.g., by an announcement at the beginning of the play- why it is being performed and what the director and actors want to communicate (253). Moreover, inviting the audience to join the actors' performance, the drama can engage the spectator's intellect, "steer him [or her] through a complex labyrinth of emotions" (253), and provoke his or her reflection about the problem presented on stage. To achieve this, the drama should incorporate a variety of art forms and a synthesis of words, music, lighting, and movement. Instead of the classical division into acts, Meyerhold proposes structuring the play using episodes or scenes, which provide more dynamism (254). Furthermore, he points to the montage technique, which theatre shares with cinema. This technique, typical of avant-garde and modernist art, rejects realism and involves a juxtaposition of contrasting, incongruous elements, which leads to grotesque effects (Pitches 61; Krouk 2). Grotesquery appears also in the inclusion of dance, which is yet another characteristic element of Meyerhold's drama (Meyerhold 141).

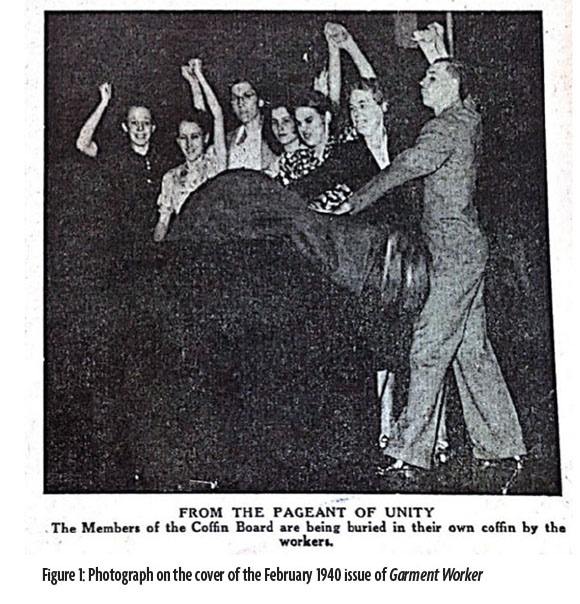

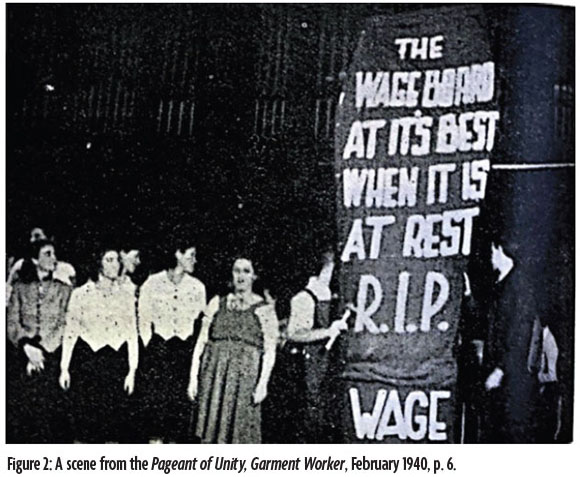

The creators of Pageant of Unity translated many of these features into the South African idiom. The February 1940 issue of the Klerewerker/Garment Worker magazine reports on the event in Afrikaans and in English, referring to the rally as "the most spectacular and colourful meeting ever held in Johannesburg" (Anon., "Crusade for a Living Wage" 3). The article, illustrated with a couple of photographs presenting scenes from the pageant, summarises the pageant's plot and the most important speeches by leading GWU activists. It informs that "the Johannesburg City Hall was packed to the capacity" and that "the enthusiasm of the crowd grew with each successive item on the programme of the Rally" (3).

The play departs from realistic conventions, relying instead on symbolism in an attempt to depict a universal workers' experience. It features generic characters representing the working-class, such as Young Woman Worker, Young Worker, Afrikaans Worker, Afrikaans Miner, and English Worker. Next to them appear allegorical figures, such as Fairy Wishfulfillment, Miss Unity/Mej. Eendrag, Hoggenheimer, and the Coffin Board, consisting of Boss MacCracker, Professor Bother, and Judge Windbag. As the pageant booklet explains, the characters of Fairy Wishfulfillment and Miss Unity/Mej. Eendrag symbolise two contrasting approaches of the workers in the face of exploitation (Trade Union Rally 10). The first one stands for the workers' apathy and wishful thinking that their problems will solve themselves. The second represents their joint effort at organising a trade union and fighting for higher wages. The Coffin Board and Hoggenheimer are grotesque figures, reminiscent of the carnival tradition. The Coffin Board mockingly refers to the Wage Board, a supervisory body responsible for the setting of wages; Hoggenheimer is, in turn, the embodiment of powerful and greedy capitalists. According to the play's stage directions, he is the personification of evil: he laughs satanically, waves a whip with his right hand, and holds a bag of money in his left hand, while being carried onto the stage on a worker's back (Routh and Weinberg 5). Well-known from a cartoon by D. C. Boonzaier, which regularly appeared in such press titles as South African News, The Cape, The Observer, The Cape Argus, and Die Burger, the figure of Hoggenheimer was stereotypically presented as an overweight character with Semitic features, and thus manifested an anti-Jewish sentiment (Shain).3

In Pageant of Unity, the Coffin Board are Hoggenheimer's servants who report to him that they have rejected "twee honderd bladsye van 'n memorandum [...], wat deur die siegte Unies voorgedra is, waarin hulle vir hoër lone vra" (a two-hundred-page memorandum drawn up by the evil Unions, where they ask for higher wages) (5).4 Hoggenheimer answers that he will send the money that he makes in South Africa to his "neefs in Wallstraat en die stad van Londen'" (cousins on Wall Street and in the city of London) (5) and that he plans to break the unity of the workers: "Nou sal ek oor die breedte van die land my spinnenrak van leuens en valse propaganda weef" (Now I will weave my cobweb of lies and false propaganda throughout the whole country) (6).

The script contains stage directions explaining the use of lighting, sound effects, and music to emphasise certain points of the play. It mentions when placards and banners, e.g., with the bilingual slogans "Eendrag maak mag!" and "Unity is strength!" or "Vir 'n vry en gelukkige Suid-Afrika!" and "For a free and happy South Africa!", should be displayed. These banners are reminiscent of newspaper headlines, and in this way the drama utilises the living newspaper convention. The play opens with the words of "The Internationale" being screened above the stage and the choir singing it together with the audience to the accompaniment of a band. The use of projected lyrics corresponds with Meyerhold's view that drama should employ certain cinematic techniques (Meyerhold 255). Moreover, seeing the words, more audience members could join in with the singing. Also, as Meyerhold (253) instructs, in the opening speech an actress referred to as Young Woman Worker addresses the audience and clearly states the message and the purpose of the play. Modestly excusing the limitations in the level of artistry of this amateur piece, she presents it as an entertaining and instructive drama and an appeal to unite in the class struggle for a better future:

Follow workers, men and women!

We shall unfold to-night

A Pageant of the workers struggle [sic]

In pictures, dazzling some and

some without much art,

We bring before you

Ideas and events.

We pray that you may pay

Not much attention to the outer shell.

We're workers all, and not masters

Skilled in arts of theatre and elocution. [...]

So that this pageant may not only

Serve to entertain you

But may give birth to life

And strength, and unity within your ranks. [.] Give birth to deeds

To action. For a future, safe from all the scourges of our days! (Routh and Weinberg 3)

Significantly, both Afrikaans and English are used throughout the play, in the lines spoken by actors and in the stage directions. Frequently words in one of these languages echo words in the other, in this way accentuating the equality of Afrikaans- and English-speaking workers in the face of capitalism and their shared goal in the class struggle:

1st VOICE. Waarom is ons hier vanaand? (Why are we here this evening?)

2nd VOICE. Why do we gather in a fighting mood?[...]

KOOR. Ons ly honger! (CHOIR. We're starving!)

YOUNG WOMAN WORKER. Yes, we're starving and we wish to starve no longer![...]

6th WORKER. And if we speak with one voice all

7de WERKER. En as ons almal saam ons sterkte kombineer (7th WORKER. And if we all together combine our strength)

CHORUS. We'll win this better life

Sal ons hierdie beteerlewe wen. (Routh and Weinberg 2-3)

In line with the working-class pageant format, the plot, "a conglomeration of scenes depicting the struggles of the South African workers for unity" (Trade Union Rally 10), questions the status quo. Instead of having a coherent plot, the drama is composed of loose episodes in which diverse problems are addressed and which culminates in the revolutionary act of overthrowing the capitalists. This composition gives an impression of incongruity and is at times grotesque, conforming to Meyerhold's proposition that modern drama be similar to a revue: a mix of song and speech (Meyerhold 254). The mood changes from scene to scene: for example, after the optimistic "Affiliate with me" song, there comes a comical, exaggerated exchange between Hoggenheimer and The Coffin Board, after which there appear banners with the dates 1914-1918 and 1939 and the "Anti-War Dialogue" in which a serious tone is mixed with absurd humour:

ALL GIRLS. Who's there?

6th GIRL. Heroes!

ALL GIRLS. Heroes who?

6th GIRL. He rose through the air with the greatest of ease,

The daring young man on the flying trapeze! (Routh and Weinberg 6)

The songs in Pageant of Unity also represent contrasting styles: the play opens with "The Internationale" and Beethoven's "Yorkscher March" described as a "fighting march", ending with a "roll of drums and fanfares of trumpets" (2), after which a lullaby is sung in English by "Woman with small child in arms" (2) and Young Man in Afrikaans. This, in turn, is followed by a song entitled "Affiliate with me", a duet in English in which Young Man invites Young Woman to join a trade union as if proposing to her a romantic relationship:

My nervous heart starts beating faster each time I'm alone with you,

I want to put a motion to this conference of two [...]

My sentiment is sympathetic to your society,

I've got an urge that we should merge,

Affiliate with me.

Why shouldn't we combine for happiness? (3)

The lyrics of all the songs to be sung during the play are printed in the brochure so the audience can join and sing along with the players, in this way co-creating the spectacle, as Meyerhold (256) proposes.

The songs, which are performed by the actors or by the choir, and the actors' speeches, are interspersed with dance interludes or tableaux similar to those used in the living newspaper dramas. The plot culminates in a dance scene representing the class struggle. A scuffle between the Coffin Board, Hoggenheimer, and the workers results in the Coffin Board ending up in the coffin, the lid of which is nailed shut by trade unions (8).

Afterwards, representatives of various groups of workers step forward, introduce themselves, and declare their joint participation in the union's effort. In this way, the play documents the history and diversified composition of the working-class. The Afrikaans Worker character speaks first, presenting his background:

Ek kom van die plaas, van die platteland

[...]

Ek is gebroke, gedrywe van my land Erfenis van my voorvadere, dis my loon

I come from the farm, from the country

[...]

I am broken, driven out of my land Heritage of my forefathers, it is my wage (9)

The declaration of class unity transcending language and cultural divisions is repeated by English Worker and Afrikaans Miner:

Eenheid werkers, dis ons lease.

[...]

Weg met rykes, klassevyand

Unity workers, this is our motto.

[...]

Away with the rich, class enemy (10)

Finally, English Women Workers declare their unity in a joint struggle for "Africa, a land of sunshine, happiness and joy! / For our children, / For coming generations" with Afrikaans Women Workers, who also want to "veg vir die vooruitgang van Suid-Afrika [...] en [...] 'n beter lewe! / en land van sonskyn, geluk en vreugde ¡bou]!" (fight for the progress of South Africa [...] and build a better life! / A country of sunshine, happiness and joy! (10). Interesting here is the discrepancy between the English and Afrikaans parts of the script. The speech of English Woman Worker is an almost exact translation of the preceding speech by Afrikaans Woman Worker, yet the English text contains an additional verse:

We pledge ourselves to-night:

All people of this land

be white their colour or be they dark

have got to live a decent life. (10)

The Afrikaans version leaves out the mention of race; compare:

Ons belowe dat almal wat werk,

van watter nasie ook,

sal 'n beter lewe lei.

We promise that all who work

of whatever nationality,

will live a better life. (10)

Afrikaans trade unionists seem to be more reserved in their declarations of workers' unity transcending the racial divide, as if carefully balancing their Afrikaner whiteness-based identification and the internationalism of the workers movement. This reflects the ambiguous attitude of the GWU's leadership towards the race issue. Even though Sachs advocated non-racialism and wanted to instil a working-class consciousness in white workers, he realised that admitting people of colour to the union's ranks on the same basis as whites was unrealistic. The union consisted of two separate branches due to the white workers' prejudice (Berger, "Solidarity Fragmented" 137-8; Witz 39).

In the final scene of the play, the actors are joined on stage by the audience while "a woman-must be a comical figure-steps forward with a big iron in her hand, which she waves about in time with her song" (Routh and Weinberg 10). The use of the hand prop, the iron, creates a grotesque effect and comically corresponds with the lyrics of the song "Stryk wyl dieyster gloei", notably sung in Afrikaans. This verse, referring to the English saying "strike while the iron is hot", contains a pun: the Afrikaans word "stryk" (to iron, an allusion to what the garment workers do) sounds almost like the English "strike". The song, therefore, is a call to take an action against the capitalists and to join a strike since the time is ripe. The drama closes on a comical note: Hoggenheimer appears again on the stage and "is beaten on the head with the iron and is chucked out by the workers" (11). Thus, the drama emphasises that workers can overthrow the exploiting capitalist when they unite.

Conclusion

Identifying the human actors, such as the theatre theoreticians and directors, and nonhuman ones, such as dramatic conventions, enabled mapping a network of connections necessary to position the GWU Pageant of Unity as a South African manifestation of international working-class culture. At the same time, this drama needs to be considered against the background of the South African pageant tradition, encompassing both British imperial and Afrikaans/Afrikaner patriotic theatrical traditions. As mass open-air events, the pageants of 1910 and 1936 celebrated a political union of the English- and Afrikaans-speaking colonial communities, and in 1938 such spectacles allowed Afrikaner nationalists to solidify their 'invented history', perpetuating the founding mythology of the Great Trek.

The GWU Pageant of Unity, much more modest in scale, represented, however, an alternative approach to the format. Not linked to the tradition of the pageants that had previously been staged in South Africa, it was modelled on the workers' drama from the Soviet Union and the United States. Its creators, Routh and Weinberg, utilised the agitprop genres and techniques which belonged to a shared inventory of socialist propaganda theatre. Routh was in particular influenced by the Russian avant-garde drama theoretician Meyerhold. The revue format, where the music, dance, movement, and dialogue alternate in a quick succession; the use of grotesque elements; and sound and lighting effects in this pageant are features of the modernist experimental theatre.

Furthermore, the GWU pageant was an attempt to propagate a shared class-based identity of Afrikaansand English-speaking workers. To this end, the players took turns speaking Afrikaans or English, echoing or complementing each other's lines. This particular use of language served to underscore the spirit of transnational socialism and to convey the message of workers' equality above ethnic and national identification. The verses in Afrikaans, however, omit the thorny issue of the interracial unity of workers, and rather accentuate the farmer-turned-worker's attachment to the African soil.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Polish National Science Centre (NCN) SONATA 14 grant (grant no. 2018/31/D/HS2/00131: "White South African New Women and cultural mobility in the first half of the 20th century").

Notes

1 . Apart from Pageant of Unity, the archives hold another undated script of a pageant entitled Labour Beats the Drum. This piece has a similar structure and depicts a history of trade unionists' struggle against capitalist exploitation. No particulars of the performance are to be found in the archive. According to Coetser (61) the play must have been performed on 1 May 1954, because the events that the text refers to date to October 1953.

2 . While a transnational approach has not been sufficiently utilised by scholars dealing with working-class literature, some historians accentuate the transnationalism inherent in South African labour history. For example, Jonathan Hyslop argues that labour movement institutions within the British Empire-including South African trade unions-should not be discussed as national organisations (Hyslop 90-1).

3 . This stereotypical figure made its first appearance in popular culture in the South African News, a Cape Town daily, on 24 September 1903. The character of the Jewish millionaire, Max Hoggenheimer, however, actually comes from a West End musical comedy, The Girl from Kays, by the English playwright Owen Hall. The play opened at the Apollo Theatre in London on 15 November 1902 and later also at the Good Hope Theatre in Cape Town where Boonzaier saw it. Afterwards the cartoonist started to use the character of Hoggenheimer, acknowledging the borrowing from Owen Hall's play (Shain).

4 . All translations from Afrikaans are my own.

Works cited

Altenbaugh, Richard J. "Proletarian Drama: An Educational Tool of the American Labor College Movement." Theatre Journal vol. 34, no. 2, 1982, pp. 197-210. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3207450. [ Links ]

Anon. "Aan 'Die Transvaler'." Klerewerker, Oct. 1938, p. 5. [ Links ]

Anon. "Crusade for a Living Wage." Garment Worker, Feb. 1940, pp. 3-7. [ Links ]

Bell, John. "Pageant." Ecumenica: Journal ofTheatre and Performance vol. 7, no. 1-2, 2014, pp. 53-8. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/ecumenica.7.1-2.0053?seq=1. [ Links ]

Berger, Iris. "Solidarity Fragmented: Garment Workers of the Transvaal, 1930-1960." The Politics of Race, Class and Nationalism in Twentieth Century South Africa, edited by Shula Marks & Stanley Trapido. Routledge, 2014, pp. 124-55. [ Links ]

________. Threads of Solidarity: Women in South African Industry, 1900-1980. Indiana U P, 1992. [ Links ]

Brink, Elsabe. "Plays, Poetry and Productions: The Literature of the Garment Workers." South African Labour Bulletin vol. 9, no. 8, 1984, pp. 32-51. [ Links ]

________. "Purposeful Plays, Prose and Poems: The Writings of the Garment Workers, 1929-1945." Women and Writing in South Africa: A Critical Anthology, edited by Cherry Clayton. Heinemann, 1989, p. 107-27. [ Links ]

Coetser, J. L. "KWU-werkersklasdramas in Afrikaans (ca. 1930-ca. 1950)." Literator vol. 20, no. 2, 1999, pp. 59-75. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4102/lit.v20i2.470. [ Links ]

Cornelius, Hester. "Eendrag teater." Klerewerker, May/June 1941, p. 11. [ Links ]

________. "Ons en die voortrekker-eeufees." Klerewerker, Oct. 1938, p 4. [ Links ]

Dawson, Gary Fisher. Documentary Theatre in the United States: An Historical Survey and Analysis of Its Content, Form, and Stagecraft. Greenwood, 1999. [ Links ]

Drwal, Maigorzata. "Afrikaans Working-Class Drama in the Early 1940s: Socialist Realism in Die Offerande by Hester Cornelius." Dutch Crossing 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03096564.2020.1723861. [ Links ]

Felski, Rita. "Comparison and Translation: A Perspective from Actor-Network Theory." Comparative Literature Studies vol. 53, no. 4, 2016, pp. 747-65. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5325/complitstudies.53.4.0747. [ Links ]

Fishbein, Leslie. "The Paterson Pageant (1913): The Birth of Docudrama as a Weapon in the Class Struggle." New York History vol. 72, no. 2, 1991, pp. 197-233, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23178785. [ Links ] "

Foley, Douglas E. "Does the Working Class Have a Culture in the Anthropological Sense?" Cultural Anthropology vol. 4, no. 2, 1989, pp. 137-62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/656273. [ Links ]

Goldstein, Malcolm. The Political Stage: American Drama and Theatre of the Great Depression. Oxford U P, 1974. [ Links ]

Greenblatt, Stephen J. Cultural Mobility: A Manifesto. Cambridge U P, 2009. [ Links ]

Hobsbawm, Eric. "Introduction: Inventing Traditions." The Invention of Tradition, edited by Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger. Cambridge U P, 2003, pp. 1-14. [ Links ]

Hummelen, W. M. H. "Het tableau vivant, de 'toog', in de toneelspelen van de rederijkers." Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal-en Letterkunde vol. 108, 1992, pp. 193-222. https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/humm001tabl0101/humm001tabl01010001.php. [ Links ]

Hyslop, Jonathan. "The British and Australian Leaders of the South African Labour Movement, 1902-1914: A Group Biography." Britishness Abroad: Transnational Movements and Imperial Cultures, edited by Kate Darian-Smith, Patricia Grimshaw & Stuart Macintyre. Melbourne U P, 2007, pp. 90-108. [ Links ]

Illustrated Encyclopedia ofWorld Theatre. Thames & Hudson, 1977. [ Links ]

Keuris, Marisa. "Taferele, tableaux vivants, tablo's en die vroeë Afrikaanse drama (1850-1950)." LitNet Akademies vol. 9, no. 2, 2012, pp. 744-65. https://www.litnet.co.za/taferele-tableaux-vivants-tablos-en-die-vroee-afrikaanse-drama-18501950/. [ Links ]

Krouk, Dean. "The Montage Rhetoric of Nordahl Grieg's Interwar Drama." Humanities vol. 7, no. 4, 2018, p. 99. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/h7040099. [ Links ]

Kruger, Loren. Post-Imperial Brecht: Politics and Performance, East and South. Cambridge U P, 2004. [ Links ]

________. The Drama of South Africa: Plays, Pageants and Publics Since 1910. Routledge, 1999. [ Links ]

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford U P, 2005. [ Links ]

Merrington, Peter. "Masques, Monuments, and Masons: The 1910 Pageant of the Union of South Africa." Theatre Journal vol. 49, no. 1, 1997, pp. 1-14. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/34335. [ Links ]

Meyerhold, Vsevolod. Meyerhold on Theatre, translated and edited by Edward Braun. Methuen Drama, 1998. [ Links ]

Nilsson, Magnus & John Lennon. "Defining Working-Class Literature(s): A Comparative Approach Between U.S. Working-Class Studies and Swedish Literary History." New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry vol. 8, no. 2, 2016, pp. 39-61. https://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/newproposals/article/view/186076. [ Links ]

________. "Introduction." Working-Class Literature(s): Historical and International Perspectives, edited by John Lennon & Magnus Nilsson. Stockholm U P, 2017, pp. ix-xviii. [ Links ]

Pitches, Jonathan. Vsevolod Meyerhold. Routledge, 2003. [ Links ]

Routh, Guy. "The Johannesburg Art Theatre." Trek, Sept. 1950, pp. 25-7. [ Links ]

Routh, Guy & Eli Weinberg. Pageant of Unity. 1940. Records of the Garment Workers Union AH1092, file Cba 2.4.2, William Cullen Library and Archive, Historical Papers, U of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Sachs, E. S. "We Declare War on Starvation Wages." Trade Union Rally and Pageant for a Living Wage / Vakunie Optog en Skouspel vir n Beter Lewe. 1940. Records of the Garment Workers Union AH1092, file Cba 2.4.2, William Cullen Library and Archive, Historical Papers, U of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Sandwith, Corinne. "'Yours for Socialism': Communist Cultural Discourse in Early Apartheid South Africa." Safundi vol. 14, no. 3, 2013, pp. 283-306. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17533171.2013.812864. [ Links ]

Shain, Milton. "'n Nuwe Hoggenheimer?" Die Burger, 7 Apr. 2016. https://www.netwerk24.com/Stemme/Aktueel/n-nuwe-hoggenheimer-20160406. [ Links ]

Tagangaeva, Maria. "Socialist in content, national in form: The making of Soviet national art and the case of Buryatia." Nationalities Papers vol. 45, no. 3, 2017, pp. 393-409. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2016.1247794. [ Links ]

Trade Union Rally and Pageant for a Living Wage / Vakunie Optog en Skouspel vir 'n Beter Lewe. 1940. Records of the Garment Workers Union AH1092, file Cba 2.4.2, William Cullen Library and Archive, Historical Papers, U of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Verwey, E. J. New Dictionary of South African Biography. HSRC, 1995. [ Links ]

Willemse, Hein. "'n Inleiding tot buite-kanonieke Afrikaanse kulturele praktyke." Perspektief en Profiel: 'n Afrikaanse Literatuurgeskiedenis vol. 2, edited by H. P. van Coller. J. L. van Schaik, 1999, pp. 3-20. [ Links ]

Witz, Leslie. "Separation for unity: The garment workers union and the South African clothing workers union 1928 to 1936." Social Dynamics vol. 14, no. 1, 1988, pp. 34-45. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02533958808458439. [ Links ]

Submitted: 28 August 2020

Accepted: 9 March 2021

Published: 8 April 2022