Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Tydskrif vir Letterkunde

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9070

versão impressa ISSN 0041-476X

Tydskr. letterkd. vol.56 no.1 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9070/tvl.v.56i1.6278

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Danai S. MupotsaI; Xin LiuII

ISenior Lecturer in the Department of African Literature at the University of the Witwatersrand. She specializes in gender and sexualities, black intellectual traditions and histories, intimacy and affect, and feminist pedagogies. Email danai.mupotsa@wits.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5338-3904

IIPostdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki and a guest researcher at the University of Gothenburg. Her current research project is entitled, "People of Smog: How Climate Change Comes to Matter." Email xin.liu@abo.fi; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5772-6414

ABSTRACT

'Stammering tongue' is the governing metaphor we offer in our reading of the border. The border, we read as a central technique of both the modern state and the violence that produces it. Our project is a diffractive encounter with the modality of implicating and complicating reading and writing. The paper offers a reading of two recent texts, Christina Sharpe's In the Wake: On Blackness and Being that draws from the metaphor/practice of the Middle Passage to offer "The Wake," "The Ship," "The Hold," and "The Weather," to theorize black violability, black death, and black living. We read Sharpe beside Jasbir K. Puar's The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability where she uses the notion of debility to stress the relations between harm, gender, race, war, and labor. We offer the 'stammering tongue,' in pursuit of a conversation between ourselves, Sharpe, and Puar. The stammering tongue is a racialized, sexualized border that produces (im)possible readings and utterances. We frame the stammering tongue as one that turns to negativity and reclaims lack to generate potentiality from that lack.

Keywords: the wake, debility, Christina Sharpe, Jasbir Puar, tongue, accent, middle passage.

Stammering, parched and trilling tongues

Instead of listening to my fellow presenters' presentations, I find myself rehearsing quietly the pronunciation of the word tongue. Tongue is the most important word for my dissertation which examines the ways in which race comes to matter in the context of Finnish language acquisition among adult migrants in Finland. My interest in tongue lies not only in the relation between mother tongue, identity, and the political economy of language, but also in the actual bodily practices of learning to speak the host country language. For example, as an adult language learner, I find it difficult to speak Finnish, especially the Finnish trill or the rolling r. The key to achieve the rolling r is the activation of the tongue tip in the form of a series of very rapid tap-like closures. For me, like many other Chinese speakers, this exercise of the tongue feels almost impossible. The /r/ becomes pronounced as /l/, which is typically perceived of as the marker/identifier of the Chinese accent. Finding in the practices of rolling r the possibility of rethinking the materiality of race, I use the term 'trilling race' as the title of my dissertation (Liu). It is not surprising that I often need to talk about tongue(s) in my presentations. However, even till now, I still can't correctly pronounce it.

"tAn"?

"/tun/"?

"/tuhng/"?

My fellow presenter is summing up her presentation. I panic. Typing the word tongue into dictionary.com for the 1000th time and putting the headphone earbud in one of my ears, "/tAn/," I listen and repeat the pronunciation quietly. Time splits. It moves forward according to the conference schedule. Tick tack, time is linear and calculated according to homogenous numerical units of measurement-second, minute, hour. At the same time, time jumps up and down, folds in and out, throws itself up and swallows itself in. Time breaks and is broken in and as the repetition of tongue ("/tAn/").

Thought that English gave me a power that I can't reach

Hoped that English would be the language that I can master

Carefully chosen, meticulously practiced

Yet my unruly Korean accent in English disclosed soon

After passing a few seconds

My accented tongue sticking out of its own will against my arduous efforts too much foreign touch, translated into untamable and uncivilized- grocery, nail salon, fish market English in the United States.

[...]

time passed like this

speechless always belated

sigh

breathlessly

bodies without words

words emptied of bodies

when words fail to fill her bodies

she seeks to fill the word in her mouth

an imaginary thing is inserted into the mouth

she craves for the food, American food

becomes her shameful secret and love object

[...]

the shame of my inadequate English

the shame of being silenced and voiceless along with other women the shame of hal-mo-ni who could not go back to hometown after serving sexual slavery the shame of o-mo-ni who utterly evacuated her mind including the memory of her baby who was left behind for adoption

those shameful memories are surfaced through my parched tongue

echoing the pains of unclaimed experiences. (Kim 39-41; emphasis in original)

In her essay, "The Parched Tongue," Hosu Kim re-members the displaced, unrecognized, and disjoined memories and bodies of Korean and diasporic subjects at different temporalities: "a Korean foreign student's loss of verbal capacity in words, a mother's memory of the Korean War, and a mother's loss of memory about the baby she left behind, juxtaposed in the form of craving for foods-binge eating and American chocolate bars" (34). Echoing the reworking of 'memorying' as the dis/ juncture between history and memory in Mupotsa's account below, I use the term 're-member' here to underscore the ways in which such a disjuncture takes bodily felt manifestations as the simultaneous displacement and relocation of tongue(s).

For example, in Kim's poem, the sense of shame and dis-ease felt by virtue of her accent is translated into the dissonance between her desire of speaking perfect English and the wilfulness of mother and othered tongues. Such a dissonance is further transvaluated into the gap between the English language that signifies capacity and upward mobility and the (accented) English language as markers of dis-ability and immobility, as well as between the ongoing and yet discontinuous process of displacement and 'memorying'-memories that are never simply or absolutely forgotten or recorded-that is felt as lack and excess, and the desire of and demand for self-presence, wholeness, location, and identity (for example the shame of her accent-the always more and less than the proper English speaking body-translates into not only silence but also the craving and appetite for consuming American food).

The broken tongue is displaced on and through and traverses multiple registers: the linguistic, the kinaesthetic, the aural, the alimentary, the symbolic, and the socio-political. And yet, at the same time, it is contained and re-located in, on, and outside the constitutive edge of racial capitalism, as the racialised, gendered, sexualized (m) other. For Kim, the double movement of displacement and relocation means that the parched tongue is the site of repression and transformation. In what follows, I consider this double movement through questions of debility and border.

In her recent book The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity and Disability, Jasbir Puar triangulates the opposition between disability and capacity through the notion of debility. As Puar (xvii) makes clear, "Debility addresses injury and bodily exclusion that are endemic rather than epidemic or exceptional, and reflects a need for rethinking overarching structures of working, schooling, and living rather than relying on rights frames to provide accommodationist solutions." For Puar, the political and analytical frameworks that focus on questions of rights and identity run the risk of obscuring the debilitation of certain bodies and populations that is the condition of possibility of disability empowerment. As she writes, "The biopolitical distribution between disability as an exceptional accidence or misfortune, and the proliferation of debilitation as war, as imperialism, as durational death, is largely maintained through disability rights frameworks" (66).

On this account, debility is not an identity category, whose reference can be located in and as a property of the body. Rather, it is (im)proper, and (non)locatable. It confounds, all the while makes possible, the imagined integral bodies of the individual speaking subject. In view of this, debility resonates with what Danai Mupotsa calls, in the next section, "Country Games, middle passages and anagrammatical blackness," the translation process without an originary whole and pure language, with the breathlessness Mupotsa feels in the name diaspora, with the plural spaces of national commitment that confound the linearity of history that Mupotsa finds in NoViolet Bulawayo's novel, with the dissolved languages and broken tongues that characterise the transnational subjectification process as Mupotsa identifies in diasporic literatures, with the breathlessness that Kim feels as the radical emptiness and excess of words and bodies, with the repetition of accented /tAn/, /tun/, /tuhng/ through, in and as my tongue, with the internal dehiscence of the tongue whose histories of oppression and wilfulness are heard and re-membered as the (in)audible stories of the (m)other(ed) tongue(s) across time and space. It is important to note that these resonances do not imply absolute translatability, where an instance perfectly mirrors another. Rather, the resonances are echoes of stammering speeches, songs, screams, silences, and sounds of swallowing and chewing, that interrupt, merge with, and perhaps even cancel out each other. Speaking in tongues is thus a refusal to the flattening out of differences in the name of inclusion, and an insistence on thinking through (im)possibilities as a political and ethical endeavor.

Importantly, the notion of debility affords an account of the bodies and populations that are not recognized as disabled or able-bodied, but challenge the very binary of disability and capacity. It follows then that interventions of and contestations against modalities of debilitation necessitate a shift from a mere focus on the hierarchical valuation of disabilities, to how processes of debilitation condition and are produced in imperialism, colonialism, and capitalist global expansion. Moreover, debility, conceived of as the in-between space, also troubles the opposition between life and death that informs biopolitical and necropolitical frameworks. As Puar (137) shows in examining Israeli state practices of occupation and settler colonialism, deliberate maiming that produces, sustains, and proliferates debilitated populations is "a status unto itself." That is, its aim is not simply making live, making die, letting live, or letting die, but to pre-emptively make impossible resistance of, and profiting from, the debilitated.

Moreover, such a reconsideration of the question of life and death also provides alternative spatiotemporal frameworks for investigating the banal lived experiences of exclusion and degradation. That is, modalities of suffering that do not fit the frameworks of liberal rights politics or the progressive temporality of nationalism, but are obscured and required by global regimes of exploitation and inequality. This is all the more important in contemporary disaster capitalism, in which relations of power are elided, and differences flattened out, in the apocalyptic narratives of the extinction of the 'we'-(hu)Man. In the context of ecological and economic crisis, the received notion of scarcity actually justifies, reinforces, and escalates forms of division between bodies that are considered worthy and populations deemed disposable. The temporality of disaster capitalism is prehensive, pre-emptive, and epidemic, informed by the received notion of death as the exceptional event at the end of life, and more specifically, the way of life of certain rather than other populations. In contrast, debility accounts for the non-linear, dispersed, banal, and affective.

This non-linearity and banality of debility is made palpable in the tongue that is broken and parched. In Kim's poem, for example, histories of displacement and oppression and contemporary racism are intertwined and translated into shameful accent, suffocating silence, uncontrollable appetite, blushed skin, as well as injured and bruised tongues. These quotidian lived experiences are typically shadowed and replaced by tales of progressive transnationalism. For example, Cáel M. Keegan observes the usage of English in dialogues between characters in the popular Netflix series Sense8, which is among the first TV shows that feature trans characters played by trans actors. The main characters located in different parts of the world are affectively bonded and are able to share skills, perceptions, and communicate through time and space. And yet, despite the emphasis on trans-aesthetics that challenges various boundaries, as well as classed, racialised, sexualized, and gendered differences, this show uses predominantly English in dialogues. As Keegan (609) writes,

By evacuating the lingual history of global colonization from the text, the program inadvertently suggests that English is a sort of psychic language that sensates share through the development of a "tongue" that transcends racialized embodiment itself. Linguistic friction-the way in which language difference sticks in the engine of globalized secular humanism-is disappeared.

In Keegan's account, the tongue becomes a prosthesis that transforms racialized bodies into exceptional transnormative bodies. The tongue "pieces" rather than passes.

Following Puar (46), I understand piecing as "the commodification not of wholeness of rehabilitation but of plasticity, crafting parts from wholes, bodies without and with new organs. Piecing thus appears transgressive when in fact it is constitutive not only of transnormativity but also of aspects of neoliberal market economies." In light of this, it could be asked which tongues are debilitated and broken and which tongues are capacitated and incorporated in and as the body of futurity. And further, how the former conditions and is required by the latter.

In the Finnish context, for example, the language skill of immigrants is considered as both a problem of, and a solution to integration. Most Finnish integration programmes for immigrants last 240 days and focus on Finnish language acquisition. However, according to the recent parliament audit committee report, some integration processes take five to seven years or even longer. Even in cases where one has quickly learned the Finnish language, the 'problem' of accents continues to function as a marker for foreignness and/as incapacity, and justifies, for example, labor market discrimination. In many cases, immigrants are asked to take other educational programs or take temporary low-paid training practices (in order to secure subsidies) after they have completed the integration program. In public discussions and political debates in Finland, the should-be integrated immigrants are said to be trapped in a vicious circle. That is, the lack of good Finnish skill is the obstacle to enter the labor market, but the workplace is considered as the best and sometimes the only place to practice Finnish. In view of this, the integration process could be considered as the in-between space of debilitation and containment, whose border is felt in and through the accented tongue-always excessive and lacking.

The tongue as a border could be read in terms of everyday bordering. As Nira Yuval- Davis, Georgie Wemyss, and Kathryn Cassidy (2) write: "Everyday 'bordering and ordering' practices create and recreate new social-cultural boundaries which are spatial in nature [...] [and] are, in principle being carried out by anyone anywhere- government agencies, private companies and individual citizens." And as Gargi Bhat-tacharyya makes clear, these borders typically fold together economic interests and cultural identities, and are constitutive of anti-migrant and anti-minority discourses in the contemporary world. In the case of accented speaking subjects, the broken tongue registers the "cut of and for racism" and of the "different spatializing regimes of the body" (Puar 55), which intersects with the process through which capitalism establishes differential access to economic activity and resources.

Viewing bordering practices in terms of differentiation more generally, it is important to note that the process of severing the inside from the outside, and self from other, goes hand in hand with practices of differentiation and fragmentation within. As Puar (21-2) writes,

Intense oscillation occurs between the following: subject/object construction and micro-states of differentiation; difference between and difference within; the policing of profile and the patrolling of affect; will and capacity; agency and affect; subject and body.

Puar's observation of the imbricated workings of discipline and control societies is echoed in Bhattacharyya's (3551) assertion of the ways in which the "machinic fragmentation" is coupled with the "attempt to fix and order bodies under the gaze of securitizing processes." The parched and broken tongue functions both as a border and as the process of fragmentation and dispersion that supplement the operation of borders, all the while as it undoes any received wholeness, such as the wholeness of language, of the tongue, of the body. Importantly, as Puar and Bhattacharyya both suggest, insofar as racism, imperialism, and capitalism operate through the differentiation of populations, the double process of locating/bordering and displacing/dispersing that takes the shape of the stammering tongue presents both the inescapability of racial capitalism and its limitations. Recall that in Kim's poem, the shamefulness of the "unruly Korean accent" is felt as a border filled with suffocating silence and emptiness. It is the sedimented effect of histories of racialization and oppression that contours the body and demarcates its inside from its outside. And yet, the shameful (m)other tongue also disintegrates itself and dissolves the bodily, spatial, and temporal boundaries so that the other (m)other(ed) tongues are re-membered.

From a slightly different perspective, however, it seems that racial capitalism is inescapable, for it remains unclear whether and how disjointed moments such as the stammer of the tongue disrupts the workings of differentiation, exploitation, expropriation. and extraction, and to what extent. Critically engaging with post-Fordist debt economy and consumerism, Bhattacharyya (3317-26) notes that capitalism of our time brings together coercion and desire "so that fear and the wish to escape become so intertwined and mutually confirming that they often cannot be distinguished." But perhaps the question whether and how to transform racial capitalism, understood as the enactment of what racial capitalism is not, needs to be reconsidered. For Puar, thinking through debility is precisely to rework the oppositional logic that informs the prescriptive politics of liberal rights frameworks and to imagine the political otherwise.

Country Games, middle passages, and anagrammatical blackness

Diaspora is a name that I inherited one time I visited home in the early 2000s. I was at a bar talking to an old friend from high school, when a man who had been listening to us hailed me by that name, "Iwe (you), Diaspora!" I left Zimbabwe to study in the United States when I was sixteen years old. By the time that I was eight (then living in neighboring Botswana with my family), I understood that while I was from Zimbabwe, my world and its aspirations would be larger than those borders. My father directed aspirations in my direction that would lead me elsewhere, always and it did not seem particularly unpatriotic to imagine a life in Europe, or the United States as a part of what it means to also be upwardly mobile and totally national in the 1980s and 1990s.

In the opening pages of her book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016), Christina Sharpe offers a definition of opportunity that I felt, in my gut, as a key relationship to borders within such a national frame:

Opportunity: from the Latin Ob-, meaning "toward," and portu(m), meaning "port:" What is opportunity in the wake, and how is opportunity always framed? This, of course, is not wholly, or even largely, a Black US phenomenon. This kind of movement happens all over the Black diaspora from and in the Caribbean and the continent to the metropole, the US great migrations of the early to mid-twentieth century that saw millions of Black people moving from the South to the North, and those people on the move in the contemporary from points all over the African continent to other points on the continent and also to Germany, Greece, Lampedusa. Like many of these Black people on the move, my parents discovered that things were not better in this "new world:" the subjections of constant and overt racism and isolation continued. (Sharpe 3-4)

The well-canonized account in Tsitsi Dangarembga's Nervous Conditions (1988) offers a lens into this relation to national space and time. The protagonist Tambudzai and her cousin/mirror Nyasha, experience a way of being in place, and not in place through various geographies or borders of lived and discursive experience. The border here, a set of complexities and opportunities related to "colonial education, class formation, and traditional patriarchy" that materialize in "Nyasha's anorexic body [which] remains the tragic junction between discourse and its embodiment" (Musila 51). The connections between Nyasha's experience of language and material of her body reveal the connections Xin Liu makes between language and the mattering of race. First published in 1988, the Zimbabwean nation seemed bound geographically through the discursive attachments that Katherine McKittrick (xi) describes as those that prioritise "stasis and physicality, [as] the idea that space 'just is,'" and towards an optimistic progressive relation to time.

It is from this place that I would like to consider "the wake," what Sharpe offers us as a problem for thought, of thinking as caring, or of "work that insists and performs that thinking needs care" (5). From this premise, In the Wake opens with a personal account of Sharpe's (8) life as "the personal here connect[s] the social forces of a particular family's being in the wake to those of all Black people in the wake," and the personal in this book is offered through Saidiya Hartman's (7) notion of the "autobiographical example," which is "to tell a story capable of engaging and countering the violence of abstraction."

The wake, as I hear Sharpe presents us with a set of temporal relations against the geography of national time. For instance, when Sharpe (9) writes that "in the wake, the past that is not past reappears, always to rupture the present," this statement is reminiscent of Pumla Gqola's attention to how collective memory is made and used; as Gqola (7) adds, "the relationship of historiography to memory is one of containments: history is always part of memory whilst history delineates a certain kind of knowledge system within the terrain of memory." I use re-memorying through Gqola's (8) visit of Toni Morrison's play with the word memory, "reassembled in [Morrison's] 're-memory' or 'memorying,' where events and knowledges are 'memoried,' 'memoryed,' 'remembered' and 're-memoried.' Morrison's word range implies a much wider field than simply collection, recollection and recalling, and it is in itself a commentary on the (dis)junctures between memory and history, working as it does not only against forgetting but also what Gqola calls 'unremembering.'"

Country Game is something that I grew up playing with my cousins at our grandmother's house. My sisters and cousins and I would draw large circles into the earth with sticks, under the avocado tree. We played for hours, competing with the names America, Russia, China, Zambia. Gogo would shout for us to play more quietly, since the large tree stood adjacent to the back rooms where her lodgers lived. I had forgotten about this game, until I was teaching NoViolet Bulawayo's novel, We Need New Names (2013), in an undergraduate course on the ways power appears or is performed in post-independence Africa. The novel is told from the perspective of children in an unnamed country that looks a lot like Zimbabwe. The protagonist, Darling, and the other children named Bastard, Chipo, Godknows, Sbho, and Stina have been moved into an informal settlement called Paradise, giving the reader the sense that this book set in Zimbabwe, against the backdrop of Operation Mu-rambatsvina, when in 2005 the government cleared people out of urban areas from their homes and businesses in an effort to 'clean up' the cities (see Vambe). There is historical precedent for operations like this from the colonial period (see Barnes), so rather than to view this as an event, it seems better to consider Operation Mu-rambatsvina as a "status unto itself," continuous with the logics of the ongoingness of settler colonialism as articulated by Xin Liu. The children now live in shacks in Paradise, and they all talk about the futures they imagine, as they steal guavas to eat from the neighboring suburb named Budapest.

Bulawayo's novel has received some criticism because of the ways that she represents the crisis in Zimbabwe (see Ndlovu), and in particular in the ways the perspective of these children and their language is framed. Silindiwe Sibanda goes as far as saying that the novel relies on racist stereotypes of black abjection. For me, the scenes Sibanda describes instead are a status unto itself, and it is also precisely in the scenes Sibanda references that the critical sharpness of the children's commentary swallows language against flat illustrations of a racist stereotype. Critics, most of all, note that the novel is characteristic of what has been described as 'Third Generation African Literature' with its emphasis on "diasporic identity, migration, transnationality, globalization and a diminished concern with the colonial past" (Krishnan 74). For Madhu Krishnan, it is not a severing from the colonial past, or a lack of national commitment as she understands it, but rather that this generation of writers present us with "plural space of national commitment" (74) and a "variability of modes of engagement with the imagined community of the nation" (94). This plural space is already evident in the ways the children speak; their language is 'broken' and 'parched' in the ways that Xin Liu describes. Making reference to the opening line of a poem in Kim's (39) essay, "The Parched Tongue"-"Thought that English gave me a power that I can't reach"-Xin Liu's parched tongue is the double movement of displacement and relocation; is the double movement of repression and transformation.

This plural space responds to "our narratively condemned status" (Wynter 70), in the ways that it potentially wakes us up. For Sharpe (14), "To be 'in' the wake, to occupy that grammar, [where] [...] rather than seeking resolution to blackness's ongoing and irresolvable abjection one might approach Black being in the wake as a form of consciousness" (emphasis in original). In Sharpe's (16) sense, the/these plural spaces of the wake, the ship, the hold, and the weather, are what enables us to "recognize the ways that we are constituted through and by continued vulnerability to overwhelming force though not only to ourselves and to each other by that force."

The middle section of We Need New Names is a very short chapter, a middle passage of sorts between Darling's life in Zimbabwe and her life in the United States titled "How They Left" that begins:

Look at them leaving in droves, the children of the land, just look at them leaving in droves. Those with nothing are crossing borders. Those with strength are crossing borders. Those with ambitions are crossing borders. Those with hopes are crossing borders. Those with loss are crossing borders. Those in pain are crossing borders. Moving, running, emigrating, going, deserting, walking, quitting, flying, fleeing-to all over, to countries near and far, to countries unheard of, to countries whose names they cannot pronounce. They are leaving in droves. (Bulawayo 145)

This middle passage has been at the heart of some of Bulawayo's keenest critics (see Harris), as it makes the central event of the novel the border between Darling's life in Zimbabwe and her life in the United States. As a question of form, the centrality of this event has been meant that the novel has been understood to fit the description of the "extroverted African novel" (see Julien).

One of the interesting aspects of form in the middle passage of Bulawayo's novel is that, unlike the dialogue between the children, or the accounts of experience we hear in Darling's narrative voice, "How They Left" is written in the third person and the language is not broken. The second half of the novel takes a more autobiographical tone from Darling's perspective: here her tongue is parched, her tenacity subdued. Yet, more generally, the broken tongue seems a feature of the Middle Passage. I am thinking about the Middle Passage, through the lens of the Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the Africa, written by Himself (1789), where in his account of the middle passage on the ship the loss of mother tongue is continuous with his subjection into chattel, a disorienting loss of the self; but also a practice of tongues that shapes the form of the slave narrative/autobiography.

As Lisa Lowe (46) contends, the relationship between liberalism and colonialism produced literary and cultural genres and the autobiography and novel both play important work in "mediating and resolving liberalism's contradictions." The autobiography, as Lowe notes, is the liberal genre par excellence. While articulating the loss of freedom/loss of tongue, Olaudah Equiano/Gustavas Vassa's narrative:

stylized the so-called transition from slavery to freedom and dramatized a conversion from chattel to liberal subject that once negotiated the voices of abolitionism and slave resistance and mediated the logics of coloniality in which trade in people and goods connected Africa, plantation Virginia, the colonial West Indies, and metropolitan England. It exemplified a fluency in the languages for defining and delimiting humanity, from liberal political philosophy and Christian theology, to the mathematical reason necessary for economy, trade and navigation. (48-9)

The narrative achieves this, but also presents moments of metalepsis, which are "moments when there is an interruption of one time by another, when there is a transgression between the 'world in which one tells and the world of which one tells,'" (Genette 54; emphasis in original). Lowe's analysis is the present time/place of 'Europe,' as she maps the emergence of an Anglo-American empire, in the work's examination of the relationships between Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

In the chapter, "The Hold," Sharpe draws the connection between the tongue and this middle passage, through her reading of the M. NourbeSe Phillip's book-long poem Zong! (2008), which retells the story of the 150 Africans who were massacred on 29 November 1871 by order of the captain of the ship named Zong. On the ship there is a failing, ripping apart of language:

Language has deserted the tongue that is thirsty, it has deserted the tongues of those captive on board because the slave ship Zong whose acquisition of new languages articulates the language of violence in the hold; the tongue struggles to form the new language; the consonants, vowels, and syllables spread across the page. [...] Language disintegrates. Thirst dissolves language. (Sharpe 69)

The 'Middle Passage' and the slave ship are the scenes for the invention and articulation of Black modernity as it has most authoritatively been presented in Paul Gilroy's 1993 account. Scholars like Yogita Goyal note the ways that, in this account, the territory of Africa itself is not only written out of the emergence of Black modernity, specifically prioritising the territory of the north Atlantic, but another effect is that the emergence of the African novel is also restricted not only to the national imaginary, but to a geography bound to that history. That is, the territory of the African novel, as an articulation of an African modernity, not only inherits a well-critiqued heterosexist masculinity in its form (see Osinubi), but the "narrative romance" (in Scott's terms) of the borders of the nation in the most recent events of anti-colonial struggles are articulated as the legitimate space/time of the nation. Diaspora, in the name of this account of the middle passage, is that which is beyond those borders of territory.

In Sharpe's (70) 'hold,' it is departures and arrivals, where language breaks, like in the case of Equiano/Vassa that those in those territories, or time/spaces of diaspora, where we experience the "residence time of the hold, its long durée." Sharpe (70) continues, "the first language the keepers of the hold use on the captives is the language of violence: the language of sore and heat, the language of the gun and the gun butt, the foot and the fist, the knife and the throwing overboard. And in the hold, mouths open, say, thirsty." "The Hold" is the story of Zong! as it is also the story of Calais (71-2), is the belly of the ship, and the birth canal, also placed in prison cells in Lilongwe (76), is a geography of the middle passage that skips over the dominance of Gilroy's territory, just as it closes Europe's territory and the history of its containments. As Sharpe (83) offers in this chapter, "the hold as it appears in Calais, Toronto, New York City, Haiti, Lampedusa, Tripoli, Sierra Leone, Bayreuth, and so on." Sharpe's hold articulates the middle passage as Paradise, as Budapest, and as DestroyedMichygen.

We Need New Names is a novel about thirsty tongues and dissolved language, in the way that Polo Moji (180) reads it as a novel that helps us to define transnational subjectification as a translational process. She offers the leitmotif of [re]naming, which is her method for reading the broken English in the novel. Moji also notes Bulawayo's own re-naming, as she grew up as Elizabeth Tshele in Zimbabwe, renaming herself NoViolet (the 'no' connoting 'with' in Ndebele, Violet the name of her mother) Bulawayo (the second largest city in Zimbabwe, where she grew up). These translations, Moji (189) argues, articulate the "dissonance of being trapped in a never-ending process of translation."

Xin Liu draws the connection between the shameful accent and Kim's relationship to food, this mirroring the hunger in Dangarembga's Nyasha. In Darling's case, even while in America, her memories of Paradise fill all the spaces of her present, so even when she describes how much food there is to eat, she doesn't feel the same hunger and talks about filling her stomach with guavas still, like in Paradise. Instead she fills herself with TV, so on days off of school she sits with her cousin TK and watches pornography while Aunt Fostalina and Uncle Kojo are at work. The television seems to act in the place that food plays in Kim, and how Darling collaborates with the ways that her tongue marks her difference. Across the cases of Nyasha, Darling, and Kim, there is a collaboration with the body, which in Lauren Berlant's (136) words "makes it a gift that keeps on giving. But gives only to her, meanwhile confirming its social negation with bodily grossness. That the two negatives of solipsism and hideousness do not make a positive here means that the rhythm of this process sets up an alternative way for self-interpretation to make something of negation." Darling's stammering is present before and after the geography of Paradise; it is a mapping of Zimbabwean/diaspora that confronts the territory of the African novel, in a logic that outruns some of its readers.

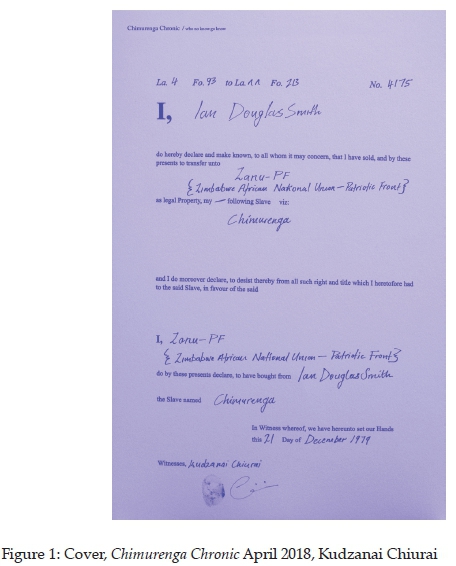

In 2018, the Chimurenga Chronic, a Pan-African literary magazine, published an issue, here a collective account, or re-memorying of the coup-not-coup titled The Invention of Zimbabwe. The cover of the issue is a 'map' made up by Zimbabwean artist Kudzanai Chiurai, whose work is often multimedia, but also often includes photographic forms (see Figure 1). The image is a form Chiurai found in the national archives in Cape Town. The form does the work of re-memorying the history of slavery in the Cape Colony, but also re-articulates the national territory with its reminders about movements of bodies and objects prior to the national moments and their territorial boundaries in Southern Africa. Chiurai fills in the form, in an act of annotation/redaction to re-mark, or re-stage the territory of Zimbabwe's national romance. Chiurai's revised contract, to mark/map the moment of Zimbabwe's independence revises an event that is most often marked in relation to a transfer of land as property, to that of the figure of the Slave. The Slave here is Chimurenga, the name given to the various anti-colonial movements that led up to the declaration of an independent state-but also to the various moments of revising nationalist history since. Chiurai's comment here is on the hijacking of Chimurenga by ZANU-PF. The contract is signed between individuals, so all, excluding the subject the Slave who is bought and sold, speak collective wishes (for imperialism, for freedom, for failure) in the subject 'I.' In my understanding, colonialism's imperative to turn the relation between land and persons to a relation of property, has had the effect of then turning the relation of person to a property relation, which is at the heart of liberalism's goal/assumption and articulation of freedom. Chiurai gives us the Slave/Chimurenga who does not speak in this contract rather than the country as our territory. Chiurai's map splits time, folds it, jumps it, and swallows it in Xin Liu's terms.

I find Chiurai's map and its subject, the Slave, to share a connection with what Sharpe (76) describes when she notes that blackness is anagrammatical: "That is, we can see moments when blackness opens up into the anagrammatical in the literal sense as when 'a word, phrase, or name is formed by rearranging the letters of another' (citing the Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online). Chiurai rearranges with this form, in the ways that Sharpe describes, revising this contract to make absent, make present the things we are not allowed to read about the nation and its time. This contract fits Sharpe's (20-1) description of the "orthography of the wake" an orthography that "makes the domination in/visible and not/visceral. This orthography is an instance of what [she] is calling the Weather; it registers and produces the conventions of antiblackness in the present and into the future." Chiurai's work in this example avoids the photograph of Africans that are often annotated with a note that responds to "a dehumaning photography [.] [where here] annotation appears like that asterisk, which itself an annotation mark, that marks the trans*formation into ontological blackness" (116). Chiurai here annotates and redacts, in the ways that asks us to see and read otherwise, "toward reading and seeing something in excess of what is caught in the frame" (117).

Rudo Mudiwa's essay, "Feeling Precarious," begins with her account of being watched by riot police in Harare in August of 2016. That day, just as crowds have been gathering in protest in 2019, people were gathered to protest the difficult conditions they were facing. As they marched towards the Minister of Finance, people were singing Chimurenga songs:

the songs allow us to rupture space and time, placing us in the bodies of young guerrillas in the 1960s who anticipated their deaths far away from home as they fought to bring the new nation into being. And then we travel further back into time and chant Nehanda's mythical last words as she died at the hands of the British South Africa Company in 1898: "Tora gidi uzvitonge." Pick up the gun so you can rule yourself.

(Mudiwa 80)

The riot police would later meet them with tear gas and batons against the flesh. In September that same year she was in a kombi, the driver playing Biggie Smalls on his radio. The driver suddenly felt suspicious about "the amount of people he saw standing around [...] He shook his head and muttered, 'Ka weather aka kanokonze-resa' [This weather will cause something to happen]" (85).

"Ka-Weather" was that sign in the stomach that gave him a sense of what was to follow, of knowledge the driver had imprinted on the flesh as Mudiwa describes it. Mudiwa's reflections are written besides four images from Chiurai's work, Revelations (2011), where men as guerrillas/Chimurenga stand in shiny spectacular ruins, images that mirror the forms of ordinary/not ordinary violence that is structured into Bulawayo's novel. Across their account they speak an "archive of breathlessness" (Sharpe 109) that I feel in my name, "Diaspora." As Sharpe (109) offers, wake work is aspiration, where aspiration is defined

in the complementary senses of the word: the withdrawal of fluid from the body and the taking in of foreign matter (usually fluid) into the lungs with the respiratory current, and as audible breath that accompanies or comprises a speech sound. Aspiration here, doubles, trebles in the same way that with the addition of an exclamation point [.] that exclamation point breaks the word into song/ moan/ chant/ shout/ breath.

Bulawayo's use of the child aspires in this way, it is the perspective of the child, it redacts in this way.

Acknowledgements

Danai S. Mupotsa would like to acknowledge the financial support of the UCAPI: Urban Connections in African Popular Imaginaries Project at Rhodes University. Danai would like to offer deepest thanks to Kudzanai Chiurai for permission to use his work. Thanks also to Ntone Edjabe and Graeme Arendse from Chimurenga.

Danai S. Mupotsa and Xin Liu would both like to acknowledge the support of the EDIT: Equality and Democracy as Transformation Project (University of the Witwa-tersrand, Helsinki University, and University of Addis Ababa) funded by the Academy of Finland (nr 320863, 2019-2022).

Works Cited

Barnes, Teresa A. "The Fight for Control of African Women's Mobility in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1900-1939." Signs vol. 17, no. 3, 1992, pp. 568-608. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/494750. [ Links ]

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Duke U P, 2011. [ Links ]

Bhattacharyya, Gargi. Rethinking Racial Capitalism: Questions of Reproduction and Survival. Rowman & Littlefield International, 2018. Kindle edition. [ Links ]

Chiurai, Kudzanai. State of the Nation. The Goodman Gallery, 2011. [ Links ]

Dangarembga, Tsitsi. Nervous Conditions. The Women's Press, 1988. [ Links ]

Edjabe, Ntone, ed. "The Invention of Zimbabwe." Chimurenga Chronic, 2018. [ Links ]

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; Or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Heinemann, 1996. [ Links ]

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge U P, 1993. [ Links ]

Goyal, Yogita. "Africa and the Black Atlantic." Research in African Literatures vol. 45, no. 3, 2014, pp. v-xxv. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2979/reseafrUite.45.3.v. [ Links ]

Gqola, Pumla D. What is Slavery to Me? Postcolonial Slave Memory in Post-apartheid South Africa. Wits U P 2010. [ Links ]

Harris, Ashleigh. "Awkward Form and Writing the African Present." Johannesburg Salon 7, 2014, pp. 3-8. [ Links ]

Hartman, Saidiya. "Venus in Two Acts." Small Axe vol. 26, 2008, pp. 1-14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1. [ Links ]

Julien, Eileen. "The Extroverted African Novel." The Novel. Ed. Franco Moretti. Einaudi, 2006, pp. 155-179. [ Links ]

Keegan, Cáel M. "Tongues without Bodies: The Wachowskis' Sense8." TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 2016, pp. 605-610. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-3545275. [ Links ]

Kim, Hosu. "The Parched Tongue." The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social. Eds. Patricia Ticineto Clough & Jean Halley. Duke U P, 2007, pp. 34-46. [ Links ]

Krishnan, Madhu. "Affiliation, Disavowal and National Commitment in Third Generation African Literature." Ariel vol. 44, no. 1, 2013, pp. 73-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/ari.2013.0006. [ Links ]

Liu, Xin. Trilling Race: The Political Economy of Racialised Visual-Aural Encounters. Abo Akademi U P, 2015. [ Links ] Lowe, Lisa. The Intimacies of Four Continents. Duke U P, 2015. [ Links ]

McKittrick, Katherine. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and Cartographies of Struggle. U of Minnesota P, 2006. [ Links ]

Moji, Polo B. "New Names, Translational Subjectivities: (Dis)location and (Re)naming in NoViolet Bulawayo's We Need New Names." Journal of African Cultural Studies vol. 27, no. 2, 2015, pp. 181-190. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2014.993937. [ Links ]

Mudiwa, Rudo. "Feeling Precarious." Transition vol. 123, 2017, pp. 78-88. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2979/transition.123.1.08. [ Links ]

Musila, Grace A. "Embodying Experience and Agency in Yvonne Vera's Without a Name and Butterfly Burning." Research in African Literatures vol. 38, no. 2, 2007, pp. 49-63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4618373. [ Links ]

Ndlovu, Isaac. "Ambivalence of Representation: African Crises, Migration and Citizenship in NoViolet Bulawayo's We Need New Names." African Identities vol. 14, no. 2, 2016, pp. 132-146. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2015.1108838. [ Links ]

Osinubi, Taiwo A. "Micro-politics of the Buttocks: The Queer Intimacies of Chinua Achebe." Research in African Literatures vol. 47, no. 2, 2016, pp. 162-185. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2979/reseafrilite.47.2.10. [ Links ]

Phillip, M. NourbeSe. Zong! The Mercury, 2008. [ Links ]

Puar, Jasbir. The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Duke U P, 2017. [ Links ]

Scott, David. Conscripts of Modernity: The Tragedy of Colonial Enlightenment. Duke U P, 2004. [ Links ]

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke U P, 2016. [ Links ]

Sibanda, Silindiwe. "Ways of Reading Blackness: Exploring Stereotyped Constructions of Blackness in NoViolet Bulawayo's We Need New Names." JLS TLW vol. 34, no. 3, 2018, pp. 74-89. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02564718.2018.1507155. [ Links ]

Vambe, Maurice T., ed. Hidden Dimensions of Operation Murambatsvina. Weaver, 2008. [ Links ]

Wynter, Sylvia. "No Humans Involved: An Open Letter to My Colleagues." Forum N. H. I.: Knowledge for the 21st Century vol. 1, no. 1, 1994, pp. 42-73. [ Links ]

Yuval-Davis, Nira. et al. "Everyday Bordering, Belonging and the Reorientation of British Immigration Legislation." Sociology vol. 52, no. 2, 2018, pp. 228-224. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517702599. [ Links ]