Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Tydskrif vir Letterkunde

On-line version ISSN 2309-9070

Print version ISSN 0041-476X

Tydskr. letterkd. vol.56 n.1 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9070/tvl.v.56i1.6271

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Imagining a politics of relation: Glissant's border thought and the German border

Moses März

Began working on his PhD research at the University of Cape Town's African Studies Unit. Currently, he is a doctoral fellow at the Minor-Cosmopolitanisms research training group at the University of Potsdam. Email: moses.marz@yahoo.de .ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7089-8731

ABSTRACT

This study explores the theoretical and political potentials of Édouard Glissant's philosophy of relation and its approach to the issues of borders, migration, and the setup of political communities as proposed by his pensée nouvelle de la frontière (new border thought), against the background of the German migration crisis of 2015. The main argument of this article is that Glissant's work offers an alternative epistemological and normative framework through which the contemporary political issues arising around the phenomenon of repressive border regimes can be studied. To demonstrate this point, this article works with Glissant's border thought as an analytical lens and proposes a pathway for studying the contemporary German border regime. Particular emphasis is placed on the identification of potential areas where a Glissantian politics of relation could intervene with the goal of transforming borders from impermeable walls into points of passage. By exploring the political implications of his border thought, as well as the larger philosophical context from which it emerges, while using a transdisciplinary approach that borrows from literary and political studies, this work contributes to ongoing debates in postcolonial studies on borders and borderlessness, as well as Glissant's political legacy in the twenty-first century.

Keywords: Édouard Glissant, politics of relation, Germany, border regime.

Introduction

In September 2006, the Martinican poet and philosopher, Édouard Glissant (19282011) was invited to speak at the opening of the International Literature Festival in Berlin. In his speech, "Éloge des différents et de la difference," Glissant (1) spoke against the background of rising levels of xenophobia in France and what he called a common failure to practice the magnetic relation to other communities. In September 2015, almost a decade after Glissant's talk, what the media referred to as the "European migration crisis" reached Germany. In breach of the already defunct Dublin Regulation, German Chancellor Angela Merkel decided to allow millions of Syrian refugees to enter the country, creating a situation of sudden social change, precedented only by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Images of Syrian refugees walking across Hungary and Austria to reach Germany where they were frantically welcomed appeared on TV screens and newspaper front pages across the world. What became known as the German 'summer of 2015' gave reason for optimism. After more than a century of 'managed migration' that was primarily geared to fuel the growth of its own economy, it appeared as if the German state was, at last, willing to reconcile its homogeneous and monolingual sense of self with the diverse reality of an immigration country.

In the opening lines of his speech in Berlin (Éloge), Glissant (1; my translation) referred to immigration as the inevitable and unstoppable "encroachment of the world" (Andrang der Welt). As Sylvia Wynter (637-8) pointed out early on in her reading of Glissant's work, borders, blockades, and blockages can be considered to be among the "root metaphors" of this oeuvre. The philosophy of relation which Glissant developed throughout his career, culminating in his lexicon-like Philosophie de la Relation (2009), can be read as an invitation to cross and transform physical and imaginary boundaries and separations and to create connections between entities that are traditionally considered apart in modern Western thought. Glissant's engagement with borders ranged from the divisions between civilizations and cultures, humans, animals, and plants, to those that differentiate literary genres and written and oral languages. My interest in Glissant's approach to borders and migration or what he called his "pensée nouvelle des frontiers' in a section of his Philosophie de la Relation (57-61), which I refer to here as his 'border thought,' arose in response to the 'German refugee crisis' of 2015. I explore the question of what his philosophy has to offer in an attempt to engage with this particular political event.

Thus far, the scholarly reception of Glissant's legacy as a theorist and philosopher has mainly taken place in the realm of literary and cultural studies with a strong focus on his ideas on language, identity, and creolization. Following the pioneering works of Robbie Shilliam and Neil Roberts, I would like to make the case for a renewed study of Glissant's work that focuses on his political theory. I understand Glissant's conception of the political to be primarily concerned with the quintessential political question of who constitutes a community and how this community relates to its surroundings. This understanding of the political entails a problematization of the neat distinction between culture and politics. Additionally, reading Glissant with this broader conception of the political allows for an exploration of the various political strategies he pursued in the radically changing geopolitical contexts shaping the last half of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first century.

The German border regime

In their engagement with the German border regime, academic studies informed by postcolonial traditions of thought appear to be closely related to a Glissantian perspective. Research in this field has focused on the institutional, structural, and cultural forms of racism underlying German society (Kilomba) and the discursive constructions of 'the Other' as the basis for a singular white and Christian German identity (Varela and Mecheril; El-Tayeb). Studies, in particularly by Kien Nghi Ha, have moreover found that the genealogies underlying the formulation of contemporary German immigration policies can be traced back to German imperial and colonial projects dating back to the nineteenth century (Ha, "Deutsche Integrationspolitik als koloniale Praxis"; "Die kolonialen Muster deutscher Arbeitsmigrationspolitik'). Another strand of scholarship has emphasized the long history of resistance against the racism perpetuated by the German border regime, particularly through self-organized migrant movements (Aikins and Bendix; Bojadzijev), that have also repeatedly highlighted the entanglements of Germany with global conflicts and structures of injustice (Dahn). Explicitly geared towards the exploration of utopian alternatives operating both within and without the existing configuration of nation-states, human rights, and the neoliberal economic system, a Glissantian perspective on the German border regime promises to enrich this body of work.

Research in the field of border studies has shown that most nation-states have no fixed external border but are in themselves complex borders that operate internally and externally (Balibar). As a case in point, Germany's external borders do not overlap with the ones of the state's territory, the European Union (EU) or the Schengen Area, but have been 'exterritorialized' through a growing number of bilateral agreements with 'third party states' that extend its southern frontier as far into Africa as the beginning of the Sahara (Luft 65). Germany plays a key role in the project of modelling the EU along the image of a gated community, where those inside enjoy free movement and security as the benefits of a global apartheid between those allowed to move and those doomed to stay or risk their lives in the process of trying to cross the borders (Mbembe 62-9). Additionally, specific laws for foreigners have turned the German border into a central aspect shaping the everyday experience of those who do not conform to the racialized norm of German citizenship, channelling their movement in ways that are designed to maintain their social status as secondary citizens (Ha, "Die kolonialen" 89). The most obvious manifestations of the internal border are the strict regulations governing the residence permit, but also the system of isolated Flüchtlingslager (asylum centres) and the mandatory Residenzpflicht (residence law), which confine the movements of refugees within the limits of the narrow district boundaries (Aikins and Bendix). The guiding rationale behind the complex disciplinary apparatus of the German border regime's surveillance-which does not exclude exceptions, as the events of 2015 have shown-is a selection mechanism geared to grant access into and movement within the country to those who contribute to the growth of the national economy (Jacoby). On a national and European level, such logic finds its discursive backing in a 'raceless racism' that defines the borders of Europe (Goldberg). While the German state and civil society were internationally lauded for making a humanitarian effort in face of the 'refugee crisis' in 2015, the celebration of its response has been criticized as cynical and amnesic in light of its overall repressive migration policy. "Soon enough the summer of grace became the autumn of rage and the winter of nightmares," writes Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung (3), "especially for the refugees who since then have become the scapegoats of all of Germany's problems." A sudden rise in arson attacks on asylum centres (Aikins and Bendix) and the strengthening of right-wing nationalist groups, among them the newly-founded party, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) (Alternative for Germany), continuing from the success of the Patriotische Europãer gegen die Islam-isierung des Abendlandes (PEGIDA) (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West) movement, led to a major discursive shift to the right. This shift resulted in the creation of a 'homeland ministry' (Bundesministerium des Innern, für Heimat und Bau) in the coalition government formed in 2018-Germany's own version of the French 'wall-ministry,' against which Glissant and Patrick Chamoiseau wrote their pamphlet Quand les murs tombent: LLidentité nationale hors la loi? in 2007.

Imagining a politics of relation: Glissant's border thought and the German border regime

As with most Glissantian concepts, anyone looking for a concise theorization of his border thought will be disappointed. To get a sense of the general direction and contour of his thinking on borders, his work needs to be read relationally, across literary genres, activism, and writing. This approach allows for connections amongst dispersed stories, approximations, comments, and poetic imagery that all relate to the question of borders and border movements. In its most overt formulations, Glissant's border thought calls for a transformation of legal borders, operating as walls that keep out and protect against the perceived danger of a racialized Other, into permeable structures that differentiate and allow for, or rather, invite the creation of relations. Borders, in this view, no longer separate between fixed entities but between more fluid phenomena, such as rhythms, smells, ways of living, or atmospheres. In what comes closest to a definition of his 'border thought,' Glissant writes in Philosophie de la Relation:

La pensée nouvelle des frontières: comme étant désormais l'inattendu qui distingue entre des réalités pour mieux les relier, et non plus cet impossible qui départageait entre des interdits pour mieux les renforcer. Lidée de la frontière nous aide désormais à soutenir et apprécier la saveur des différents quand ils s'apposent les uns aux autres. Passer la frontière, ce serait relier librement une vivacité du réel à une autre.

The new border thought: that which, from now on, is the unforeseen that distinguishes between realities in order to better relate them, and no longer the impossible that decides between that which is forbidden to better re-enforce it. The idea of the border helps us to support and appreciate the taste of differences, when they are attached to one another. Crossing a border would be to freely relink one liveliness of the real to another. (Glissant, Philosophie 57, original emphasis)

Here borders remain necessary because of what Glissant perceives to be the importance of "highlighting and contrasting between different landscapes" and ways of living, as opposed to the homogenizing project of neoliberal globalization (Glissant, Une nouvelle région du monde 22).

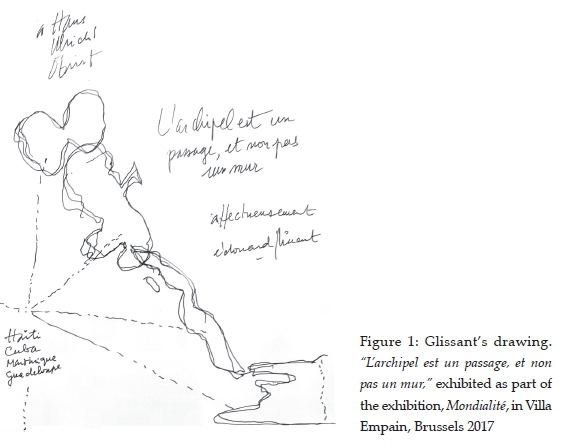

Glissant's border thought is informed by the Caribbean landscape. For instance, he points out that it would be impossible to convincingly define the borders separating the individual islands making up the Caribbean archipelago, because their borderlines would always shift with the waves of the ocean (Glissant, Philosophie 57-8). In a drawing titled, "llarchipel est un passage, et non pas une mur' ("The archipelago is a passage, and not a wall") (see Figure 1), Glissant illustrates this view by placing several islands of the archipelago in such a way that their borders overlap at several points and are drawn with multiple, uncertain lines.

The islands of this imaginary map are in direct relation with one another, an expression of what Glissant considers to be a natural Caribbean commonality due to a shared landscape, culture, and history that contradicts the geographic and political differences that persist between them as a result of different colonial projects. The notion of the archipelago is furthermore suggestive in this context since it alludes to his border thought as being invested in exploring alternative shapes for political communities that fall outside the model of sovereign nation-states and federations.

Conceptually, Glissant's border thought is articulated primarily through his vision of the Tout-Monde, or whole-world, which he also imagines in the form of an archipelago and describes as a "non-universal universalism" made up of an infinity of differences undergoing constant and unpredictable changes (Glissant, Traite du Tout-Monde 176). Through this lens, questions pertaining to the German border regime would ask: what could be done to transform borders from walls into points of passage, enabling relations? And what other forms of political communities does Glissant's imaginary of relation enable us to envision in this context?

In addition to the general conception and normative horizon of his border thought, an engagement with his key concept of 'relation' is of crucial importance in formulating a response to these questions. In his analysis of social and political issues, Glissant has repeatedly pointed out that socio-political problems, be they conflicts, socio-economic issues, or widespread xenophobia, are tied to deeper cultural conceptions held by particular communities that inform their relations with the world. Failure to foster a relational imagination can result in a range of individual and collective psychological imbalances, translating into a collectivized fear of the Other. In my understanding, the concept of relation operates on all levels pertaining to the lives of individuals and collectives, across spatial, temporal, visible, and invisible dimensions. Its awareness of relations to all kinds of 'Others'-be they animals, plants, cultures, or humans (Glissant and Chamoiseau 25)-overcomes established categories of social analysis and opens up the mind to a whirlwind of complexities that create the sense of vertigo evoked in Glissant's definition of relation as "la quantité réalisée de toutes les differences du monde, sans qu'on puisse en excepter une seule" ("the realized quantity of all the differences of the world, without leaving out a single one") (Glissant, Philosophie 42, original emphasis). In addition to the general relational thrust of a Glissantian study of the German border, I will refer to a further set of concepts-"mythe fondateur" (foundation myth) and "opacité" (opacity). I use the former as a way of engaging with the historic narrative informing the contemporary German border regime, and the latter as a way of engaging with a set of cultural underpinnings. Additionally, I consider the notions of the small country and the archipelago to offer a productive political model against which current German immigration policies can be measured and alternatives to it imagined.

Notes towards a Glissantian study of the German border regime

Due to the scope of this discussion, I am not proposing an exhaustive Glissantian study of the German border regime. The main aim of my approach is to suggest a new vocabulary and historical framework to the ongoing debate on the European migration crisis that emerges out of a study of Afrodiasporic literatures.

Re-relating German histories

Glissant proposes to differentiate the narratives underlying what he calls "atavist" or "composite" countries according to whether they take the form of a "foundational myth" as Genesis or filiation, legitimizing a people's claim to a particular territory or a "myth of elucidation" that seeks to offer an explanation for the encounter of diverse elements making up a social structure (Glissant, Introduction à une poétique du divers 60, 62). This binary classification is connected to two opposing conceptions of identity, one informed by a thought of "single roots" that kills its surroundings, the other by what Deleuze and Guattari have termed the rhizome, which "extends by encountering other roots" (59). Whereas foundational myths operating with a single root imaginary exclude the other as participant and lead to atavist conceptions of community, myths of elucidation, which are explicitly told in relation to others, are the discursive basis underlying creolized communities (63). For Glissant (Poétique du divers 61), the problem therefore becomes: how can the imaginaries of the world be changed from atavistic notions of culture to creole ones?

Taking Glissant's concept of the foundational myth as a point of departure, we can begin to study to what degree the narrative underlying the German national community suggests the existence of an atavist or creole country. As in the Martinican case, where Glissant (Le discours antillais 391-2) pointed out how the "African element" was systematically disavowed as a constitutive cultural part of creole culture, cases where the presence, participation, or contribution of "others" have been systematically negated or disavowed need to be analyzed. This would not only concern the presence of 'guest workers' arriving from Southern European countries Post-World War II, but also Polish seasonal workers at the time of the Prussian Empire, as well as people from across the globe who came to Germany through its colonial enterprises. The same goes for the acknowledgement of attempts to completely exterminate the Other from the national body, as was the case during the Holocaust. A fundamental acknowledgement of these dynamics as constitutive for a culture taking on a composite or atavist form would shape the description of the foundation myth.

Once an understanding of this official discourse has been established and certain atavist elements identified, a Glissantian approach sets out to contrast it with an account that aims at re-relating the pieces of history that have been held separate or made invisible. Outside the official discourse, the parts forming this relational account of German history have and still are being formulated, in writing and through actions. These "relational sparkles" (Chamoiseau 89) include networks of solidarity for and among refugees, large-scale demonstrations against repressive immigration policies and for the acknowledgement of the diversity of people living in the country, activist initiatives for the restitution of stolen cultural objects on display in museums and for the recognition of the genocide of the Nama and Herero and its memorialization in German history. This already-existing politics of relation takes place in everyday interpersonal interactions, art galleries, theatres, cultural institutions fostering transnational exchanges and cultural journals. This kind of critique or counter-discourse intervenes in the existing political system with the aim of opening up the construct of German identity, from homogeneous to diverse, and its positionality in international relations, from superiority to equality, with the goal of evoking a more general shift from nation-states to relation-states.

Embracing the other's opacity

A Glissantian study of the German border regime offers a second direction, which approaches the cultural question more directly as the matrix on which the historical narrative or German founding myth outlined in the previous section can be imagined and maintained. Of central importance for a cultural disposition towards rela-tionality for Glissant is what he calls the respect for opacity. As much as the secrets guiding the events of the universe will, in the final instance, remain inexplicable, Glissant (Nouvelle région 187) insists that the preferences and motives behind our actions will remain essentially opaque to both the self and the other. The acceptance of the other's opacity can therefore be perceived as the precondition for developing an imaginary of relation and an awareness of the Tout-Monde, both on the level of the individual and the collective. Not insisting on transparency, the necessity of knowing or fully understanding the other or turning them into the same does not preclude the possibility of friendship, love, and other forms of solidarity in Glissant's view. Quite the opposite. In the same way that he insists that it is possible to like or work with someone without fully "knowing" them, he considers the "refusal of that which one does not understand" to be the quintessential disposition of racists (Glissant and Diawara 14).

In his anthropological studies concerning the contemporary global refugee crisis, Michel Agiers has attributed a frequent sense of disappointment among activists assisting refugees to a cultural disposition requiring transparency and sameness as a basis for social interaction. Perceiving 'the migrant' either through a juxtaposition of dominant and dominated individuals ("au nom de la souffrance," in the name of suffering), a resemblance between the self and the other ("au nom de la ressemblance," in the name of identity) or an aestheticization or exoticization of otherness ("au nom de la différence," in the name of difference), results in an absence of relationality in Agiers' view. This absence produces a shared sense of distrust and frustration on both sides (Agiers ch. 1).

In this context, a Glissantian study operates with a distinct set of normative standards for measuring the relational wealth of cultures. Against the view of culture as a static and hierarchical construct, replacing the concept of race in its classical biological form (Goldberg 334), Glissant (Nouvelle région 66) perceives cultures as fluid constructs and as ways of thinking and being in the world that mutually enrich one another in a process of "changing by exchanging-without losing or denaturing oneself." Instead of justifying an alleged cultural superiority through the economic productivity of certain countries, Glissant argues that an over-valorization of economic productivity should be replaced by valorizing the ability of particular cultures to relate to the diversity of the Tout-Monde. On the level of the individual, this means that the worth of human beings is not measured in economic terms or according to the ideal of the "human work machine" that works as steadily as it works intelligently (Ha, "Die kolonialen" 95). As a result, 'foreigners' in this kind of culture would not occupy the lowest possible socio-economic sphere, out of a fear that they "take the jobs of locals," or be unable to fully participate economically through a lack of language proficiency. Instead, they would be given preferential treatment as newcomers and contributors to the survival of the culture that would die without their revitalizing input (Glissant and Chamoiseau 3).

Towards the creation of "small countries"

Countering the atavist foundational myth and accepting the other's opacity, as outlined in the previous two sections, already allude to alternative ways of being together that could transform contemporary border regimes into the points of passage as called for by Glissant's border thought. In this last section, I want to pursue the exploration of its theoretical and practical potentials through Glissant's concepts of the archipelago and the small country. Archipelagic thought perceives the world as a collection of islands that constitute a whole in which the relations between individual parts are of essential importance (Glissant, Philosophie 45). Glissant (45) opposes the image of the archipelago to that of a continent, the former being associated with diversity, fragmentation, and uncertainty; the latter with homogeneity, completion, and certainty. Glissant (llintention poétique 153) extends his vision of the Caribbean as a political model to the world when he proclaims his "belief in the future of small countries." Transferred to the context of borders and migration, I consider these images as not only offering a different imagination for how immigration policies within nation-states can be constructed, but also as offering a different model for political communities outside the nation-state paradigm, which I will outline below.

Working with the concepts of the archipelago, a Glissantian study of the German border regime could, as a first step, explore the ways in which national homogeneity and the perception of a political community as a closed and coherent whole is being produced. Such a study could begin by identifying particular paradigms informing the formulation of immigration policies. In the case of Germany, a recent shift from the 'guest worker' model to the 'integration' paradigm would fall into this category. The 'guest worker' model was maintained for more than a century in order to prevent the country from becoming an 'immigration country' by urging migrants to return home after a temporary contribution to the growth of the economy. According to Ha ("Die kolonialen" 64, 69), this model has its roots in a logic of the "inversion of colonial forms of expansion," in which the productivity of the Other is used without taking the risk of territorial occupation. The integration paradigm, beginning in the early 2000s, replaced the guest worker model after its alleged failure. Instead of demanding migrants to return to their countries of origin, the integration paradigm demands cultural assimilation to the national Leitkultur (leading culture) (Pautz), which can be translated as the imperative of turning migrants into Germans (Münkler 199). Discursively, Ha ("Die kolonialen" 91) also traces the genealogy of this model to colonial fantasies of "taming the wild" and the civilization mission, a reading which Glissant's (Nouvelle region 83-4) commentary on the integration of migrants in France, growing out of the French colonial doctrine of assimilation, echoes. In his Traité du Tout-Monde, Glissant (210) denounces the integration paradigm as a "great barbarity:"

La créolisation n'est pas une fusion, elle requiert que chaque composante persiste, même alors quelle change déjà. '['integration est un rêve centraliste et autocratique. La diversité joue dans le lieu, court sur les temps, rompt et unit les voix (les langues). Un pays qui se créolise n'est pas un pays qui s'uniformise. La cadence bariolée des populations convient à la diversité-monde. La beauté d'un pays grandit de sa multiplicité.

Creolization is not a fusion; it requires that each of its composite parts persists, even if they are already changing. Integration is a centralist and autocratic dream. Diversity plays itself out in places, it moves with the times, breaks and unifies voices (languages). A creolizing country is not a standardizing country. The colourful cadence of populations suits the world-diversity. The beauty of a country grows out of its multiplicity.

As made explicit by this quote, Glissant's border thought problematizes the notion of integration as a violation of human dignity. For the receiving culture, it is also a self-amputation which deprives itself from potential enrichment through the engagement with others. Achieving 'real integration' in Glissant's (Nouvelle région 172, 207) view, requires working on the basis of acknowledging the other's opacity and the possibility of relating without submitting them to a singular cultural standard. Once the guiding rationale underlying the contemporary border regime is established, in a second step, the specific measures used to 'turn migrants into Germans' could be studied. In the German case, the two instruments that are prone to receive particular attention in this context are the 'integration course,' which requires migrants from vaguely classified non-Western countries to take up to 945 lessons of German language, law, culture, and history as a precondition for permanent residence (Ha, "Deutsche" 137), and the practice of scattering refugees across the federal states according to a strict numeric quota calculated through the number of inhabitants and tax revenue (Leitlein, et al.). I will here briefly focus on the second policy instrument since it links more directly to the image of the archipelago as a counter-model to culturally homogenous nation-states. In the process of scattering newcomers across the territory, families are separated across the different federal states that make up the German Republic (Bundesländer) and confined to movement within its borders by a mandatory Residenzpflicht (Aikins and Bendix). The rationale behind this division, which goes against the preferences of the individuals and communities concerned, as well as considerations of available housing and the actual material resources of the federal states, is based on the fear of avoiding the creation of so-called "parallel societies" (Parallelgesellschaften). For instance, the Berlin districts of Kreuzberg and Neukõlln, to which most Turkish immigrants moved in the 1960s and 1970s, are regularly referenced in public discourses as deterrence. Instead, the guiding rationale of this policy is that through a high degree of isolation of these families, their cultural differences will eventually 'dissolve' into the dominant culture of their surroundings. The result of the policy of scattering refugees across largely isolated rural areas is not only that sustaining community networks is made more difficult, but also that refugee camps in isolated parts of the country are particularly vulnerable to xenophobic attacks (Pro Asyl).

As pointed out above, a Glissantian politics of relation is based on the belief in the progressive force of creolization and are fundamentally opposed to an enforced cultural "fusion." Instead of working towards a dissolution of differences, it aims to work towards supporting cultural differences, not in the form of segregation or an explicit disintegration, but as a way of supporting the vital needs of migrant communities in the form of establishing "small countries" or "parallel societies." These would not be left to their own devices but would be provided with all the infrastructure needed in order to maintain their political, economic, and cultural networks and practices. Whether against the will of German policy makers or with their help, this process is already taking place in districts like Berlin-Neukõlln and Kreuzberg, in which the second largest number of Turkish nationals after Istanbul reside. And, as a result of the 'summer of 2015,' new spaces within Germany will eventually accommodate "islands" largely populated by Syrian nationals.

Conclusion

Taking up the task issued by Glissant in his 2006 Berlin speech to imagine a politics of relation, I explore border thought in response to the contemporary migration crisis and Germany's border regime. Working with Glissant politically, translating his philosophy in such a way that it can be referred to as a tool for political analysis and for the imagination of alternative policy approaches to immigration, requires an engagement with the philosophical and conceptual foundations of his border thought and its connections to Glissant's overall commitment to the creation of communities that are attuned to the archipelagic structure of the Tout-Monde.

In addition to the general normative thrust of his border thought, against which contemporary border regimes can be measured, it is possible to identify a set of directions which a more comprehensive Glissantian study of German borders could take. Working with the concepts of the foundational myth, opacity, and the archipelago has proven to be particularly productive as ways of engaging the historical narrative, the cultural disposition, and the policy framework underlying German immigration politics. In each case, it is not only possible to sketch the contours of a Glissantian critique but also to point to practical alternatives that a politics of relation suggests, moving the utopian thrust of his border thought into the realm of the possible. When coupled with his approach to borders, Glissant's concepts of the archipelago and the small country, in particular, suggest the invention of new political formats beyond the nation-state, of which the city appears as a particularly productive space to experiment with practical expressions of a relational imaginary.

Works Cited

Agiers, Michel. Les Migrants et nous: Comprendre Babel. Kindle Edition. CNRS, 2016. [ Links ]

Aikins, J. K. & D. Bendix. "The 'Refugees Welcome' Culture." Africasacountry. 16 Nov. 2015. https://afric-asacountry.com/2015/11/resisting-welcome-and-welcoming-resistance. Accessed 19 Feb. 2019. [ Links ]

Aufenthaltsgesetz (Gesetz über den Aufenthalt, die Erwerbstàtigkeit und die Integration von Auslàndern im Bundesgebiet) (Immigration Act), 2004. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/aufenthg_2004/. Accessed 19 Feb.2019. [ Links ]

Balibar, Étienne. "Borderland Europe and the Challenge of Migration." Open Democracy. 08 Sep. 2015. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/borderland-europe-and-challenge-of-migration/. Accessed 19 Feb. 2019. [ Links ]

Bojadzijev, Manuela. Die windige Internationale: Rassismus und Kampfe der Migration. Westfàlisches Dampfboot, 2012. [ Links ]

Castro Varela, María do Mar & Paul Mecheril (eds). Die Damonisierung der Anderen. Rassismuskritik der Gegenwart. Transcript, 2016. [ Links ]

Chamoiseau, Patrick. Frères migrants. Editions du Seuil, 2017. [ Links ]

Dahn, Daniela. "Der Schnee von gestern ist die Flut von heute." Und das ist erst der Anfang. Ed. Anja Reschke. Rowohlt Polaris, 2015, pp. 187-201. [ Links ]

El-Tayeb, Fatima. Undeutsch: Die Konstruktion des Anderen in der Postmigrantischen Gesellschaft. Transcript, 2016. [ Links ]

Glissant, Édouard. "Éloge des différents et de la difference/ Lob der Unterschiedlichkeiten und der Differenz." Trans. Beate Thill. Opening speech at the 6th International Festival of Literature Berlin, 05 Sep. 2006, Haus der Berliner Festspiele, http://www.literaturfestival.com/medientexte/eroeffnungsreden/rede-glissant-2006/view. Accessed 19 Feb. 2019. [ Links ]

_____. Introduction à une poétique du divers. Gallimard, 1997. [ Links ]

_____. llintention -poétique. Gallimard, 1997 (1969). [ Links ]

_____ . Le discours antillais. Seuil, 1981. [ Links ]

_____ . Philosophie de la Relation. Gallimard, 2009. [ Links ]

_____ . Traité du Tout-Monde. Gallimard, 1997. [ Links ]

_____ . Une nouvelle région du monde. Gallimard, 2006. [ Links ]

Glissant, Édouard. & Manthia Diawara: "Édouard Glissant in Conversation with Manthia Diawara." Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, no. 28, 2011, pp. 4-19. www.muse.jhu.edu/article/453307. Accessed 8 Jun. 2012. [ Links ]

Glissant, Édouard & Patrick Chamoiseau. Quand les murs tombent: l'identité rationale hors la loi? Editions Galaade and Institut du Tout-Monde, 2007. [ Links ]

Goldberg, David T. "Racial Europeanization." Ethnic and Racial Studies vol. 29, no. 2, 2006, pp. 331-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870500465611. [ Links ]

Ha, Kien N. "Deutsche Integrationspolitik als koloniale Praxis." Kritik des Okzidentalismus: Transdisziplinäre Beiträge zu (Neo-) Orientialismus und Geschlecht. Eds. Gabriele Dietze, Claudia Brunner & Edith Wenzel. Transcript, 2009, pp. 137-50. [ Links ]

_____ . "Die kolonialen Muster deutscher Arbeitsrrügrationspolitik.'' Spricht die Subalterne deutsch ? Migration und postkoloniale Kritik. Eds. Encarnación Gutierrez Rodriguez & Hito Steyerl. Unrast Verlag, 2003, pp. 56-107. [ Links ]

Jacoby, Tamar. "Germany's Immigration Dilemma: How Can Germany Attract the Workers It Needs?" Foreign Affairs vol. 90, no. 2, 2011, pp. 8-14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25800452. Accessed 19 Feb. 2019. [ Links ]

Kilomba, Grada. Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism. Unrast Verlag, 2008. [ Links ]

Leitlein, H, et al.. "Hier wohnen Deutschlands Asylbewerber." Die Zeit, 20 Aug. 2015. https://www.zeit.de/gesellschaft/zeitgeschehen/2015-08/fluechtlinge-verteilung-quote. Accessed 19 Feb. 2019. [ Links ]

Luft, Stefan. Die Flüchtlingskrise: Ursachen, Konflikte, Folgen, Chancen. Zentralen für politische Bildung, 2016. [ Links ]

Mbembe, Achille. Politiques de l'inimitié. Editions la découverte, 2016. [ Links ]

Münkler, Herfried. "Die Satten und die Hungrigen: Die jüngste Migrationswelle und ihre Folgen für Deut-schland und Europa." Und das ist erst der Anfang. Ed. Anja Reschke. Rowohlt Polaris, 2015, pp. 187-201. [ Links ]

Ndikung, Bonaventure S. B. "Whose Land Have I lit on now? Contemplations on the Notion of Hospitality." Savvy Contemporary exhibition concept. May-Jun. 2018. https://savvy-contemporary.com/en/projects/2018/whose-land-have-i-lit-on/. Accessed 19 Feb. 2019. [ Links ]

Pautz, Hartwig. "The politics of identity in Germany: the Leitkultur debate." Race & Class vol. 46, no. 4, 2005, pp. 39-52. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396805052517. [ Links ]

Pro Asyl. "Gewalt gegen Flüchtlinge: Von Entwarnung kann keine Rede sein." 28 December 2017, https://www.proasyl.de/news/gewalt-gegen-fluechtlinge-2017-von-entwarnung-kann-keine-rede-sein/. Accessed 19 Feb. 2019. [ Links ]

Roberts, Neil. Freedom as Marronage. U of Chicago P, 2015. [ Links ]

Shilliam, Robbie. "Decolonizing the Grounds of Ethical Inquiry. A Dialogue Between Kant, Foucault and Glissant." Millenium: Journal of International Studies vol. 39, no. 3, 2011, pp. 649-65. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829811399144. [ Links ].

Wynter, Sylvia. "Beyond the Word of Man: Glissant and the New Discourse of the Antilles." World Literature Today vol. 63, no. 4, 1989, pp. 637-48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/40145557. [ Links ]