Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Tydskrif vir Letterkunde

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9070

versão impressa ISSN 0041-476X

Tydskr. letterkd. vol.55 no.3 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9070/tvl.v.55i3.5506

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Symbolic values of the dog in Afrikaans literature

Gerda Taljaard-Gilson

Independent lecturer at Unisa's Department of Afrikaans and Theory of literature. Email: gerdagilson@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The dog is a universal, archetypical symbol of fidelity and loyalty. However, in literature-and especially in South African literature-the dog (as well as the hyena and the wolf) often symbolises the diabolical. In some instances the dog is also symbolic of the dark side of human nature, of dehumanisation and even of death. The canine symbol in Afrikaans literature has both European and African origins. When canines appear in their natural (literal) form in Afrikaans poems and narratives, they are for the most part portrayed in a positive (compassionate) way. As soon as they appear in a figurative (allegorical) capacity though, as a symbol or metaphor, they mostly represent something ominous. The ambivalent nature of dogs-they are both caring and brutal-is reflected in Afrikaans literature. In this article the contradictory (symbolic) depiction of canines will be explored in various Afrikaans poems and novels. This article thus falls within the framework of animal studies, the interdisciplinary field which analyses how nonhuman animals are portrayed and viewed within literature.

Keywords: Afrikaans literature; ambivalent portrayal of dogs; animal studies; symbolic value of the dog.

Introduction

In this article the contradictory portrayal of dogs will be scrutinised within the context of animal studies. Animal studies is a component of the larger research area of ecocriticism, which involves studying the interaction between literature and the physical environment; in other words, nature and the appearance of natural phenomena, such as vegetation, rock formation, soil, water and especially non-human animals. The theorists of animal studies consider animals as part of our social and political narratives-from the first tales about the migration of human animals as hunter-gatherers, to the "grand narrative" about human domestication and the agricultural transformation, as well as part of our religious practice, social rituals and literature (Swart 273). Animal studies does not only take the portrayal of nonhuman animals in literature into account, but also the issue of animal rights and the ethical interaction with animals within literature.

Because of Biblical views, that man is "the crown of God's creation", but also due to the Age of Enlightenment (1685-1815), which has viewed man as the centre of the universe, nonhuman animals are mostly regarded as subordinate, emotionless and, above all, unintelligent-creatures that should be ruled over and controlled. The purpose of animal studies is often to deconstruct this species-oriented (speciesist) way of thinking, as well as bridging the gap between the human "self" and the nonhuman "other" (Crous 373). During our colonial past, indigenous animals (and people) were documented as "the other", as "beasts" that were tamed, domesticated, studied, suppressed and even wiped out in a striving for prosperity. We have, in other words, not only held prejudices against certain human races but also against certain animal species. Dogs and other related species, for instance wolves, foxes and jackals, have for centuries been depicted in literature as evil, sly and cruel. On the other hand, pets are often seen as a mere extension of ourselves, resulting in anthropomorphism in literature, where animals are given human characteristics.

According to Mthathiwa (4) there are three ways in which animals are depicted in literature: naturalistic, allegorical and compassionate. A naturalistic depiction involves the realistic representation of the nonhuman animal in its natural habitat. In allegorical depictions, non-human animals are figuratively portrayed as a metaphor for man and his (often cruel and foolish) nature. Compassionate depiction is mostly used for the portrayal of pets and often suggests how human beings are supposed to treat animals; that there is a close relationship between human and nonhuman animals. In this article these categories of animal depiction will be applied to various literary texts.

In South African literature, both real and imaginary animals have always played a decisive role. The aim of this article is to contribute to and expand on the area of animal studies by examining the ambivalent portrayal of canines in recent and older texts within Afrikaans literature. This will be accomplished by tracing the origin and development of the dog as a literary symbol; by analysing various poems and novels with canine symbolism; and by discussing a variety of canine symbols. Because of the dog's close relationship with humans, animal studies concerning dogs do not only contribute to the history of canines, but also tell us a lot about ourselves.

The dog as a symbol: origin and development

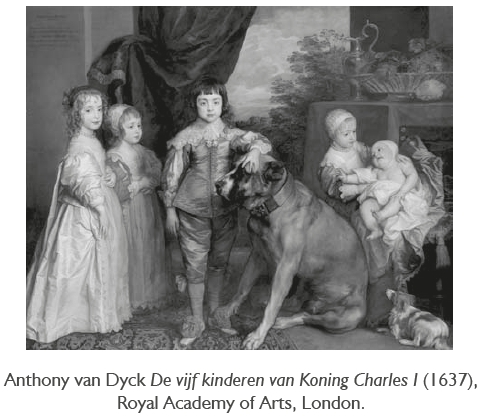

Although the domestic dog (Canis familiaris) has acted as companion to humanity for the last 12 000 years and is often termed "man's best friend", it is only since the European Renaissance that dogs developed a more positive connotation as trustworthy and dependable domestic animals. This fact is attested to by the many paintings commissioned during and after this period of dogs and their owners. The most celebrated of these is possibly the Flemish baroque painter Anthony van Dyck's painting De vijf hinderen van Koning Charles I (The five children of King Charles I), which depicts the British royal children with both a mastiff and a spaniel (painting reproduced below). The dogs in this painting are clearly depicted as part of the family; as beloved pets and not merely as hunting or herding dogs.

Thus dogs became a symbol of loyalty, security and fidelity. Due to this positive association, dogs were often symbolically included in marriage portraits of especially the early Renaissance, for instance in Jan van Eyck's De Arnolfini-bruiloft (The Arnolfini Wedding Portrait). At the feet of the married couple is a small dog that symbolises conjugal fidelity (Bersson 413). According to Schneider-Adams (557), however, the dog could also symbolise sexual drive and it furthermore points to the high social status of the couple, since only the aristocracy could afford to keep dogs exclusively as pets and not as working animals.

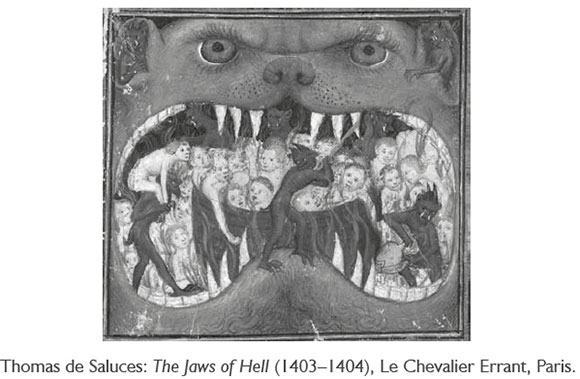

In the thousand years preceding the Renaissance, during the Medieval period, dogs were mostly viewed-partly due to Biblical influence-as unwholesome scavengers that carried and spread contagious diseases such as rabies. This view was strengthened by the large amount of stray dogs that preyed on everything dead and rotten. This also serves as an explanation for the negative portrayal of dogs in Medieval works of art (see the painting reproduced below, by French artist Thomas de Saluces) and manuscripts, amongst others the very well-known Faus-tian legend (adapted by Goethe to the tragic play Faust), where the devil takes on the appearance of a stray dog on first meeting Faust.

The reference to dogs in the Bible (in both the Old and the New Testament) is predominantly negative. In 1 Kings 21:19 King Ahab is warned that the dogs will lap up his blood on the same spot where they lapped up Naboth's blood. In Psalm 22:16 the Psalmist compares his enemies to a pack of dogs surrounding him. Matthew 15:26-27 refers to a false preacher as a dog that returns to its own vomit-hence the Afrikaans expression: "hy is soos n hond wat terugkeer na sy eie braaksef (he is like a dog that returns to its own vomit), used in the context of someone that relishes their own, or someone else's, evil deeds. In fact, most Afrikaans sayings involving dogs carry a negative meaning: "Iemand soos n hond behandef (to treat someone like a dog); "so siek soos n hond" (to be as sick as a dog); "haastige hond verbrand sy mond" (a hasty dog burns its mouth); "eie honde byt die seerste" (the tamest dog has the most vicious bite); "hond se gedagte kry" (to have a dog's suspicion); "moenie slapende honde wakker maak nie" (let sleeping dogs lie).

This negative connotation with dogs, and, by extension, wolves, foxes, jackals and hyenas, has also found its way into literature. Despite the mostly amiable temperament of domesticated dogs, they are, nonetheless, still genetically closely related to wolves, foxes and the jackal. Domesticated dogs still share-after thousands of years of evolution-behavioural patterns with their wild ancestors (Van Sittert and Swart 139-41). Both domestic and wild canines are protective of their territory and mark this with urine; in addition all canine species bury their food in an attempt to preserve it for later; and all canine species communicate through their sense of smell and body language. Thus the domesticated dog is often viewed in the same (unfavourable) light as wolves, jackals and foxes; and in literature dogs, and their wild relations, often feature as a universal symbol of evil, death, cruelty, animalistic impulses, instinctive impulsivity and uncontrollable carnal drive-thus the darker side of human nature.

As a universal symbol, the dog represents evil in the literature of various languages and cultures the world over. Within Afrikaans literature two poems by poet N. P. van Wyk Louw, "Die strandjutwolf" (The brown hyena) and "Ballade van die bose" (Ballad of the diabolic) from the anthology Gestaltes en diere (Apparitions and animals), serve as examples of the negative connotation associated with the canine species. Furthermore Peter Blum's poem "Drosterhonde bo Oranjesig" (Runaway dogs above Oranjezicht) from Steenbok tot Poolsee and Petra Müller's "Tormentoso I" (from Die aandag van jou oë) (The attention of your eyes) can also be mentioned in this context. Writers of prose who made use of this trope include Anna M. Louw in Wolftyd (Time of the wolf) and in Vos (Fox); Corlia Fourie in her short story "Wolf-se-vrou, mevrou doktor Wolf en me. Wolf" (Wolf's wife, Mrs doctor Wolf and Ms Wolf) from Liefde & geweld (Love & violence); Alexander Strachan's novel Die jakkalsjagter (The jackal hunter) and more recently Willem Anker's Buys: n Grensroman (Buys: A pioneering novel).

The compassionate portrayal of dogs (as pets)

There are also many literary texts in Afrikaans where dogs are portrayed in a positive light. The two dogs Toby and Gerty in Marlene van Niekerk's Triomf (English translation with the same title) are not only lovable pets but also the only friends that Mol, Pop, Treppie and Lambert have. In Jeanne Goosen's n Pawpaw vir my darling (A pawpaw for my darling), the story is told from the perspective of a mongrel Tsjaka; and in her novella Louoond (Warming oven) the main persona's two Dobermans are sympathetically described-even though they kill the neighbours' chickens.

It seems as if dogs are portrayed as kind and lovable when they appear in a literal capacity (naturalistic presentation) within literature. However, when they are used allegorically their portrayal usually evokes negative connotations associated with evil and death. This depiction of dogs in Afrikaans literature has both European and African roots: the wolf as an antagonist in various European fables, and the hyena/jackal as a malefactor in African orature. T. O. Honiball's Jakkals-en-Wolf (Jackal-and-Wolf) stories, entertaining fables in which these two unsavoury title characters constantly try to outwit each other, is an excellent example of how the portrayal of Canis species in Afrikaans literature was influenced by both African and European traditions. According to Verster (443) the Medieval Dutch fable Van den vos Reynarde/Reinaerde had a definite impact on Honiball's stories, but the trickster characters also resonate with the antagonists in African folklore, especially in Khoisan fables.

In Ilse van Staden's novel Goeie dood wat saggies byt (Good death that gently bites), which deals with the trials and tribulations of a young veterinary surgeon, there are many references to loving dogs (as pets). However, the title of the novel also points toward dogs as a symbol of death. The vet is made aware of "die dun spanningslyn tussen lewe en dood" (222) (the thin, tense line between life and death) by her occupation. When a pet dies under her care, she feels personally responsible and is confronted by her own mortality. She comes to realise that death manifests in two distinct ways: "the good death that gently bites" (compare the title), in other words the peaceful demise of both human and animal, and the "harsh death" which is coupled with tremendous pain and suffering.

In John Miles' novel Op n dag, n hond (One day, a dog), the dog who crosses paths with the main character, eventually becomes more than just a normal dog: he develops figurative qualities and symbolic value. The dog becomes a symbol of the nameless character's haunting conscience and guilt.

Although the children's verse "Waghondjies" (Little watch dogs) by Jan F. E. Celliers (reproduced below) portrays dogs as loyal guardians that will protect their owner with their lives, it is exactly this quality that also serves as a threatening element within the poem.

Little watchdogs

I am here, and Mom is here,

we are lying on Master's jacket.

Who are you?

Come, get away,

if not, our grunt will become a grab-

your legs might get a bite.

Your trousers might look a sight.

Smooth talk? No, we know you not.

Away with your hand and touch us not!

"Look after it," our master said,

"until I'm back, you will remain."

On our paws we put our heads,

but we are still watching you.

On the jacket we are sleeping,

but we are still peeping-

one ear flat, one ear up

Even in this children's rhyme, there is a contradiction with regard to the depiction of dogs. The ambivalence in the nature of canines-both lovable and threatening-comes to the fore (also symbolically) in many Afrikaans poems, short stories and novels. In the following sections this contradictory symbolic depiction will be explored in various Afrikaans literary texts.

"Sy wit oë agter my": The canine as a symbol of the diabolical and death

The brown hyena (Hyaena brunnea) is a scavenger that is mostly active at night; in Van Wyk Louw's poem though, the brown hyena takes on a far more sinister (allegorical) dimension than merely that of a scavenging animal searching for food on a farmyard:

The brown hyena

It only comes with the dark moon:

from afar I hear its call

like something lamenting in the veldt;

then it is at the porch ...

he sniffs at the threshold softly

and stirs around the house,

I hear him wheezing, breathing

and at the kitchen scratching;

the whole yard is full of him:

there where the ploughs are shining,

there I see his ox-like shadow moving

and hear something metal clanging.

I know he is gray and large,

that if he gets up straight

his paws are scratching at the roof,

he listens in at the chimney ...

and when I am lying in my room

and everything is still and black,

then I know it is in the house,

I listen to my heart,

I know his eyes are pale and blind,

I hear him softer than a sob

here in the passage and in between

the ticking of my watch,

and when the daylight comes I know

the Grey One is with me,

I hear his trotting and I feel

his white eyes behind me. (Louw 19, own translation)3

There are a number of indicators from the poem that the hyena in the text becomes symbolic of something dark and supernatural-"his eyes are pale and blind"; "Grey One"; "white eyes behind me". In the poem the speaker's childlike fear of the unknown progresses to become the existential fears of an adult. The speaker seems to fear that the hyena could break into the safety and security of the family home (almost like in the fairy tale of the three little pigs). Within the context of the anthology Gestaltes en diere (Apparitions and animals) (1942), the hyena represents the diabolical. According to Visagie (6) the hyena is also indicative of the disruptive influence of irrational forces of nature on humanity, whose closely delineated cultural existence is threatened by this (nature versus culture) and of the insidious influence of African culture on the essentially European settler farmer trying to eke out an existence in Africa. Visagie (6) further elaborates on this idea:

The African wilderness-becoming manifest in the form of the hyena-moves ever closer to the person of the speaker in his small enclave of tamed Africa, until it-similarly to N. P. van Wyk Louw's "Ballade van die bose" (Ballad of the diabolic)-follows the speaker like a dog. The hyena ultimately turns out to be a stalker but also a companion that enters into a narrow bond with the speaker. (Visagie 6, own translation)

Both poems-"Die strandjutwolf" (The brown hyena) and "Ballade van die bose" (Ballad of the diabolic) (compare stanzas four and five below)-also contain, apart from the threat posed by the two "animals", suggestions of rapprochement. Both poems suggest an entanglement between humanity and evil-implying that evil, like good, forms an inseparable part of what makes people human (Kannemeyer 141-2).

I am in you

twisted, entangled

like a root

in dark earth,

and before dawn's

white light begins

I shine into both your eyes [...]

I am the underground

of your being

and I walk in your tracks

like a good dog. (Louw 15, own translation)4

N. P. van Wyk Louw was probably aware of the unfavourable depiction of the hyena within African folklore and fables when he wrote "Die strandjutwolf". Due to their nightly activity, hyenas are associated with witchcraft. Furthermore, sometimes the male hyena devours its own offspring. Thus in Zulu folklore, the hyena (impisi) is an evil, treacherous, devourer-of-men that disrupts the communal order and undermines the central protagonist. The impisi has a lot in common with another treacherous figure associated with trickery from indigenous African culture-the Izimu. He is half-man, half-animal and according to Canonici (54) he personifies "human anxieties and fears". The hyena in African fables is in other words the counterpart to the wolf in European fairy tales; examples of this would include Little Red Riding Hood and The Three Little Pigs, where the wolf is an evil antagonist who tricks the protagonist.

The hyena, however, does not only symbolize evil or the "irrational forces of nature" (Visagie 6), but also death. In Northern Sotho there is a proverb: "O swerwe diphiri" (the wolves took him), in other words, "he is dead". The lyrical subject in N. P. van Wyk Louw's "Die strandjutwolf " (The brown hyena) not only expresses his fear of evil, but also of death. The idea that there exists a bond, even an affinity, between humanity and death is also not excluded.

"'n Wyfiewolf se heldersiende oë": the wolf as symbol of the wild woman

Poet Petra Müller created the collection of poems Die aandag van jou oë: gedigte vir die liefde (The attention of your eyes: poems for love) during and after the illness and death of her husband Wilhelm Grütter. Thus, the anthology consists of elegiac love poems in which the poetic voice struggles to come to terms with the death and loss of her beloved companion. The poems record the different stages of mourning: the initial denial, reproach, lamenting, anger, honouring the deceased, finding peace and ultimately acceptance and comfort.

Initially the poet-speaker cannot bear the gaze of her dying husband, (compare the title of the anthology), especially in the poem "Lamplig" (Lamp light) in which the speaker expresses the paradoxical wish that the events on which the anthology is centred, and the anthology itself, should not take place (Viljoen 570). However, through the course of the anthology the loss of her husband's gaze becomes unbearable as the realisation sinks in that she has lost the fixed attention of those eyes-compare the poems "sig" (sight) and "Die aandag van jou oë" (The attention of your eyes)- because they are now focussed on another horizon, probably death.

In several poems death manifests as a canine figure, for instance in "In die uitgrawing" (In the excavation) (stanza 4) where the lyrical subject assures her sick husband that the dogs (the threat of death) has passed for now:

Listen how quiet it has become around us.

There is nothing sniffing about now.

The tumult is over, the howling bitches,

the militia dogs are gone. (Müller 36, own translation)5

In "Tormentoso I" (stanzas 2-3) the person addressed in the poem is threatened with the stormy sea (with which the speaker associates herself) and a brown hyena:

May the hyena who has learned how to hunt in the daylight

find you and clean you up [...]

May you become bait like a baby seal [...]

You are not lost. You will be digested in my insides.

I am your sand, your sea, your wolf [...] (Müller 38, own translation)6

In "Spoor" (Footprint) (stanzas 2-4) it seems the speaker's beloved has become a brown hyena himself, as if death has become a part of him, resulting in a more positive depiction of the hyena:

you call-

you have that strange little bark

moisture drips from your fur

you have a hunger

which I with my clear streams

can feed no more (Müller 37, own translation)7

In "Tormentoso II" the canine symbolism takes on an entirely different (more favourable) shade of meaning. The wolf is now a "she-wolf", representing the wild woman, who does not experience death as a threat but as a fellow traveller and companion in life. When she looks in the mirror, she sees the "heldersiende oë" (clairvoyant eyes) of a she-wolf and the dog at her feet is "verwonderd/oor die

wilde vrou" (bewildered/by the wild woman). The woman, purified through suffering the loss of her beloved, not only gains deeper insight in the course (and denouement) of life, but also grows to associate herself with the she-wolf and thus with death and the intuitive and instinctive nature of the wild woman-the woman who has freed herself from the restrictive roles of mother and serving wife. She drinks a toast on her "bewilderment". She thus celebrates her new unattached, untamed status:

Tormentoso II

at night she pours a lonely glass of wine

and drinks it with delight

she walks the rooms with a bulbous glass

in a place which once was her home

and she listens to the storm: there is a dog

keeping at her feet, bewildered

by the wild woman

and sometimes, when the roof wants to lift

she holds the glass up and drinks a toast

on bewilderment:

was that a shiver?

because as she spins around, in the mirror

there drift a she-wolf's

clairvoyant eyes. (Müller 129, own translation)8

In Women who run with the wolves: myths and stories of the wild woman archetype, Jungian psycho-analyst Clarissa Pinkola Estés draws a comparison between women and wolves. The wild woman who is attuned to her intuition, instinct and primal knowledge is, like the wolf, an endangered species because the passionate, untamed nature of women is denied, neglected and above all oppressed by society. Through the use of myths, legends and folktales women can once more come into contact with the creative and visionary powers of their psyche: "Wild Woman comes back. She comes back through story" (Estés 26). According to Estés wolves and women also share a psychological bond with regard to their fiery nature, mystery and devotion to their life-partners and communities because women-like wolves-can rely on their intuition and instinct. She encourages women to return to their wolf-like nature in order to come to terms with the ambiguities contained in their psyche as both loving caretaker and aggressive protector:

Healthy wolves and healthy women share certain psychic characteristics: keen sensing, playful spirit, and a heightened capacity for devotion. Wolves and women are relational by nature, inquiring, possessed of great endurance and strength. They are deeply intuitive, intensely concerned with their young, their mate and their pack. They are experienced in adapting to constantly changing circumstances; they are fiercely stalwart and very brave. Yet both have been hounded, harassed and falsely imputed to be devouring and devious, overly aggressive, of less value than those who are their detractors [...] The predation of wolves and women by those who misunderstand them is strikingly similar. (Estes 4)

By comparing women to wolves in this way, it appears that Estés has bridged the gap between the human "self" and the nonhuman "other"-an issue which concerns the adherents of animal studies.

Anna M. Louw's Wolftyd: The wolf as a symbol of Nazism

The title of Anna M. Louw's novel Wolftyd (Time of the wolf) refers to the Second World War. It indicates an inhumane time but also refers to the "alleenloperwolf" (lone wolf) Luk, the main character's husband, who as a young man, desperately wanted to be a Nazi.

In German mythology the "Time of the Wolf" is an age just prior to the twilight of the gods-an age in which people have become like wolves: familial love has atrophied and an age of war, violence and betrayal has dawned. "Time of the Wolf" is also a time period in which the devil temporarily has the upper hand on earth (Van der Merwe). In Louw's Wolftyd it is then also hinted at that Hitler was diabolically possessed (24-5; 162), and it seems as if all hell has broken loose in the marriage of the characters Leonie and Luk. In fact Leonie goes so far as to invite a religious group to her house to cast the devil from it (76). Ultimately, however, the "devils" that confront Leonie are far more subtle and sly and she will only be rid of them after a long period of soul searching and spiritual purification (Van der Merwe).

More specifically, in the novel, the concept of "the time of the wolf" has bearing on the history of Germany under the spell of Hitler and the Nazis, where compassion and humanity have disappeared and Europe was experiencing the hell of a world war. The "time of the wolf" is clearly applicable to Luk, the deceased husband of the main protagonist-Leonie. Luk perishes in an atmosphere of intense, all-inclusive fury: "Schweinerei!" (Damned charlatanry!), is his summary of life. With regard to himself, he expresses the desire: "Töte mich!" (Kill me!) (33). From the notes and documents that Leonie discovers after his death, she comes to realise that he has not been faithful in their marriage. It is a real possibility that Luk deliberately left these documents for Leonie to discover as a form of macabre revenge. The time following Luk's death is a "wolf time" for Leonie, but after his passing Leonie comes to realise that the years of their marriage was also a "wolf time" (Van der Merwe).

A close relationship exists between Luk's "wolf time" and the "wolf time" of the Nazis. Luk is a "Mischling"-someone who is partly of Jewish descent. As a result of this, Luk-who wanted to join the Nazi movement-becomes an outcast who has to flee Germany. This results in his intense hatred of the Nazis but also, because he wanted so desperately to be accepted by the Nazis, in a hatred of himself. Luk's hatred and anger against both himself and the Nazis becomes a cancer that extends to everyone he comes into contact with, to life in general and ultimately even to God.

This hate is coupled with a life of lies and deceit. Luk attempts to hide his partly Jewish identity. This refusal to come to terms with his identity results in him living a lie and foreshadows the deception he practises on his wife. Nazi chauvinism also leaves its mark on Luk: he acts superior towards women (213) and is a "toepasser van koue seks" (practitioner of cold sex) (216). Thus Luk's life becomes a reflection of the Nazi "wolf time" on a micro-scale (Van der Merwe).

Willem Anker's Buys: the dog as a symbol of the savage and the unconfined9

Willem Anker's Buys: A Pioneering Novel is introduced by a motto which is derived from Peter Blum's poem "Drosterhonde bo Oranjesig" (Runaway dogs above Oranjezicht) (stanza 1 reproduced below). In this poem the lyrical subject questions why domesticated dogs would stray from the protection of "friendly roofs" and from "food in big bowls" to lead a nomadic existence in the mountains where they are exposed to "bleak winter weather". Thus the expectation is created that (runaway) dogs will play a pivotal role within this historical novel.

What went wrong with them, with those mongrels?

to abscond from kind neighbourhoods

where they were under friendly roofs

protected from bleak winter weather

-where they had everything a dog could ever

ask for in its simplicity? food in big bowls

(despite the high cost of living)

a fireplace to nestle next to at night

within our atmosphere, our aroma;

almost every evening a walk with their owner,

and, when they fell ill, the treatment

of a vet with a diploma!

sniffing parties on street corners

and the daring rag slacks

of the delivery guy-

those mutts-what could have bothered them? (Blum 16, own translation)10

The stray dogs that announce their barking presence early on in Buys (16), indeed form an important component of this text in that they become a symbol of that aspect of humanity that cannot be contained or controlled by the rules of civilization (compare the subtitle of the novel: A Pioneering Novel). This would indicate the push against boundaries and borders-be it national borders or social boundaries. Buys refuses to be contained within any borders. In this regard Snyman states the following:

Time and again Buys and his followers throw off the shackles of a specific place and circumstances and push the boundaries. They trek beyond the Eastern Frontier and go to live in "Kaffirland", then they uproot there and trek further, across the border of the Cape Colony towards the North. All the different political borders mean equally little to Buys, as do the people who determine and maintain those borders. The whole novel is a protest against political borders. (3)

Buys-and the pack of dogs that follows in his wake-deliberately leaves behind order, security and comfort and becomes a stray dog himself, similar to the dogs in Peter Blum's poem "Drosterhonde bo Oranjesig" (Runaway dogs above Oran-jezicht) that do not abide by the norms, but claim a different way of life for themselves.

On more than one occasion Buys rebelled against the authority of the Cape Colony-he disrespected the judges, as representatives of the English overlords. He trekked from the Colony to the Eastern Cape and the region beyond the Fish River. Just like geographical borders, social and racial borders could not contain him. His first wife was a brown woman, Maria. His second wife was Nombini and his third, the young black woman Elizabeth. In between he also married Yese, the mother of the young tribal leader Ngqika. Wherever he went he sired children, also with several women outside of wedlock. In fact, it seems as if he was delineating a new colony and created a nation of his own, not only with all his offspring, but also with the vagabonds that he surrounded himself with, including the pack of dogs that followed him.

The dogs in Buys become, on an allegorical level, a sort of alter-ego for Coen-raad de Buys, especially after he bites off an ear of one of the dogs during an altercation with the pack (23-4). In this way he "caught some sort of ailment from the creatures" (26); he becomes physically stronger and his sense of hearing and smell become enhanced: "Notice how I sniff the morning air, my nose uplifted like a snout? How I look up, alert, before anyone has heard anything yet?" (25).

Buys is the manifestation of "dog-eats-dog", of "man-becoming-dog". Just like the dogs, Buys cannot be tamed-it is in his nature to rebel, to destroy and to kill. Like Buys, the dogs are also runaways constantly locked in a battle for survival. The dogs become a part of Buys' existence; they understand each other's unspoken language. When Buys and his company are on the trek, the dogs are constantly somewhere in the surrounds. The pack of dogs becomes Buys' companion unto death: "When the pack saw him again, half-a-moon later, he [Buys] was crouching on all fours, the gun and powder-horn dangling under his stomach. His fur hung loose, his knuckles were bleeding" (427). Buys becomes fully animal, he ends as an "onmens" (unhuman). Like the dogs, Buys is an outsider, an "outlaw" who, as mentioned before, cannot be contained or bound by the laws and boundaries of the Cape Colony: "I piss on border posts. I ruffle my pelt and draw up my lips to expose my teeth" (141). The dogs start to follow him and, like the dogs, he leaves behind all forms of order and civilization to scavenge "vleis en bloed en kuf (meat and blood and cunt) (213). Thus there is still another point of similarity between Buys and the dogs: their brutality, violence and overriding urge to copulate.

The pack of dogs that follows Buys into the wilderness is in a constant process of transformation. They become all the more wild, start to resemble wolves and become increasingly estranged from civilization and domestication. In this way they increasingly become a symbol of the primal, the human subconscious "where there is no active censor of civilization" (Snyman 7). In the same way, a new manifestation of Buys comes to the fore with each relocation: Buys the Reckless, Buys the Dangerous, Buys as Khula, Buys the loving husband and father, Buys the farmer from Lange Cloof and finally Buys that becomes fully animal in his old age when he sniffs at his one wife with his "snout", his hands "mere paws" (425).

Buys is the outsider, the rebel, the barbarian, "the-kill-whatever-and-who-ever-stands-in-my-way", the revolutionary. Buys also represents the dark side of human nature; he represents the subconscious and the savage side of being human, the lecherous man who cannot control his urges-humanity without its varnish (Snyman 1; 7). Yet, Buys is capable of rational thought, he can reason and possesses the ability to convince, and at times he even seems philosophical. More than this he is the writer, the narrator of his own story: "I am the legend Coenraad de Buys. Come, let me infest you, my inherently burdened reader" (Anker 1).

The ambivalence in the nature of dogs, being both nurturing and cruel, also manifests in Buys. Indeed, there is more than one Buys, he is endlessly complex and impossible to pin down (Van Schalkwyk 4). One version of Buys loves his children, another version is unfeeling towards others and nature. One Buys is sensitive and emotional, the other cruel. One is crude, the other a practical philosopher (Snyman 6).

Buys increasingly became a person that did not belong anywhere and who could not find rest and settle down. He became a stranger who realised that he will never find a home. Human describes Buys' displacement as follows:

Nowhere did the nomadic Buys manage to root down permanently. Towards the end of the novel he and his "Buysvolk" have wandered up to the banks of the Limpopo river but, as for Moses who led the Israelites from Egypt, arrival in the Promised Land -in this case the Tswapong hills-was not to be. (7)

The dog as a symbol of Afrikaner identity

The dogs in Buys do not only serve as a symbol of humanity's primal subconscious and as Buys' alter-ego but also as a medium which facilitates an alternative view on Afrikaner identity and history. In similarity to the dogs, only the strongest and most cunning of pioneers would survive the wilderness: "Here we devour each other. Christians, Dutch, Germans, French, Kaffirs, Bengalis, Hottentots, Bushmen and what not. It is one huge hunting ground!" (219). Ironically, Buys himself rejects all categories of identity and refuses to group himself with any one people or culture.

The titular character Coenraad de Buys (1761-1820) is a genuine historical figure that trekked across several political boundaries in order to escape the authority of the Cape Colony and the British government. Long before the Great Trek left the Cape Colony, Buys had already trekked into the interior of South Africa and fathered several children. Today his descendants still live in Buysdorp, which is situated between Louis Trichardt and Vivo in the Limpopo province (Steyn and Van Heerden 4). It is this part of history and this legendary figure that Willem Anker attempts to conjure through writing his historical novel Buys, since it seems as if Coenraad de Buys has disappeared to a large extent from official accounts of South African history. Perhaps he has been omitted purposely, probably because he became known as "die koning van die basters" (the king of the mixed-breeds) (Snyman 2) and progenitor of a nation whose origins transgressed the law under Apartheid.

Historical fiction comprises narrative texts that use history and historic events creatively, usually in order to evoke a specific period in history. Authors pen a piece of history that has been neglected or omitted from official accounts and in so doing become the "first historian" of this piece of history, though in fictional form. Historical novels thus serve the purpose of documenting or archiving aspects of history that are threatened with obliteration. Central to the history syllabus traditionally taught in South African schools were accounts about the pioneering settlement of Europeans in the region, wars against indigenous inhabitants and of course the Great Trek-the narrative of European settlement in Africa. Contrasting to this traditional narrative, Willem Anker foregrounds through the novel Buys that there are also other versions of history and other historical narratives that differ from the singular perspective that has traditionally been offered (Burger 22).

The reading (and writing) of historical fiction is often a search for identity precisely because one has to consider and reconsider one's own place in history and at times acknowledge one's own culpability implied in a specific piece of history (Taljaard-Gilson). Furthermore, historical fiction is used to create a "historical conscience" in the contemporary reader by accounting for a controversial past. In Buys the controversial aspect of pioneering history-the pioneer's unconscionable and abusive actions against fellow humans and nature-is laid bare. Buys (and his canine companions) represent the Afrikaner who tamed the wilderness through bravery and resourcefulness but also through cruelty and oppression. In this novel Willem Anker successfully bridges the gap between human and nonhuman animal: within the character of Buys they become one: inseparable, undistinguishable. On the other hand, the novel comments, from the perspective of animal studies, on the pioneer's disrespect and extreme cruelty towards nonhuman animals.

Conclusion

The dog is an ambiguous symbol with many meanings and manifestations. By examining a variety of older and more recent Afrikaans literary texts within the context of animal studies, it was found that the canine as a symbol can represent the diabolic, death, the wild woman, Nazism, the dark side of the human psyche, the savage and the unconfined spirit, as well as Afrikaner identity. It was also determined that when dogs appear in their natural form within poems and narratives, they are portrayed in a positive (compassionate) light. However, as soon as the dog appears on a figurative (allegorical) level, it usually symbolises something menacing. Furthermore, it was found that the ambivalence in the nature of dogs, being both nurturing and cruel, leads to the contradictory values assigned to the dog as a symbol in Afrikaans literature. On the one hand it can symbolise man's animalistic aggression, his brutality and savagery; on the other hand the canine is a symbol of fidelity, of man's striving for freedom and belonging, and even of the emancipated woman. The exploration of the dog as a symbol within the framework of animal studies, has not only revealed the ambivalent depiction of dogs in literature, but also the complex nature of humankind, that good and evil co-exists within us.

WORKS CITED

Anker, W. Buys:n Grensroman. Kwela, 2014. [ Links ]

Bersson, R. Responding to Art: Form, Content and Context. McGraw-Hill Humanities, 2004. [ Links ]

Blum, P. Steenbok tot Poolsee: Verse. Tafelberg, 1955. [ Links ]

Burger, W. "Kies 'n Boek-Buys: n Grensroman". Vrouekeur, 27 Feb. 2015, pp. 22-3. [ Links ]

Canonici, N. N. "Tricksters and Trickery in Zulu Folktales." Diss, U of Natal, 1995. [ Links ]

Celliers, J. F. E. Die saaier en ander nuwe gedigte. De Bussy, 1918. [ Links ]

Crous, M. "'Sonder siel en anoniem': Elisabeth Eybers se 'Huiskat' in die konteks van dierestudies." Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 373-386, 2015. [ Links ]

Estes, C.P. Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Women Archetype. Ballantine, 1992. [ Links ]

Fourie, C. Liefde & geweld. Tafelberg, 1991. [ Links ]

Goethe, J. W. von. Faust. Afrikaans trans. Eitemal. Nasionale Boekhandel, 1966. [ Links ]

Goosen, J. n Pawpaw vir my darling. Kwela, 2006. [ Links ]

_. Louoond. HAUM-Literêr, 1987. [ Links ]

Human, T. "Grootse roman skep 'n eie taal." Die Volksblad, 10 Nov. 2014. [ Links ]

Kannemeyer, J. C. Die Afrikaanse literatuur 1652-1987. Academia, 1988. [ Links ]

Louw, A. M. Wolftyd. Tafelberg, 1991. [ Links ]

_. Vos. Tafelberg Publishers, 1999. [ Links ]

Louw, N. P. van W. Gestaltes en diere. Tafelberg, 1942. [ Links ]

Miles, J. Op n dag, n hond. Human & Rousseau, 2016. [ Links ]

Müller, P. Die aandag van jou oë: gedigte vir die liefde. Tafelberg, 2002. [ Links ]

Schneider-Adams, L. Art Across Time. McGraw-Hill Humanities, 2002. [ Links ]

Snyman, H. "LitNet Akademies-resensie-essay: Buys deur Willem Anker." Litnet. 7 Nov. 2014. <www.litnet.co.za/Article/litnet-akademies-resensie-essay-buys-deur-willem-anker>. Accessed 12 Sep. 2017. [ Links ]

Steyn, P. & C. van Heerden. "Op Buysdorp is almal familie." Beeld, 2 Apr. 2016. [ Links ]

Strachan, A. Die jakkalsjagter. Tafelberg, 1999. [ Links ]

Swart, S. "'But where's the bloody horse?' Textuality and corporeality in the 'Animal Turn'." Tydskrif vir literatuurwetenskap vol. 23, no. 3, 2007, pp. 271-92. [ Links ]

Taljaard-Gilson, G. "'n Ondersoek na die waarde van historiese fiksie: drie geskiedkundige romans in oënskou geneem." LitNet Akademies. 12 Feb. 2013. <www.litnet.co.za/n-ondersoek-na-die-waarde-van-historiese-fiksie-drie-geskiedkundige-romans-in-oenskou/#Artikel>. Accessed 16 Oct. 2017. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, C. ""Wolftyd-Anna M. Louw". LitNet-Leeskringe. 1999. <www.oulitnet.co.za/leeskring/wolftyd.asp>. Accessed 12 Sep. 2017. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, M. Triomf. Queillerie, 1994. [ Links ]

Van Schalkwyk, P. "Our hunting fathers." Litnet, 9 Dec. 2014. <www.litnet.co.za/Article/biebouw-resensie-buys-en-our-hunting-fathers>. Accessed 16 October 2017. [ Links ]

Van Sittert, L. & S. Swart. "Canis Familiaris: A Dog History of South Africa." South African Historical Journal vol. 48, 2003, pp.138-73. [ Links ]

Van Staden, I. Goeie dood wat saggies byt. Protea Boekhuis, 2016. [ Links ]

Verster, F. P. "'n Kultuurhistoriese ontleding van pikturale humor, met besondere verwysing na die werk van T. O. Honiball." Diss. U of Stellenbosch, 2003. [ Links ]

Viljoen, L. "Petra Müller." Perspektief en Profiel: Afrikaanse literatuurgeskiedenis. Deel III. Ed. H. P. van Coller. Van Schaik, 2016, pp. 561-78. [ Links ]

Visagie, A. "Moderniteit en die Afrikaanse literatuur." Inaugural speech delivered on 16 May 2016. U of Stellenbosch, 2016. [ Links ]

1. Waghondjies / Ek is hier, en Ma is hier, / ons twee lê op Baas se baadjie. / Wie is jy? / Kom, loop verby, / anders word ons knor 'n daadjie - / kry jou bene dalk 'n hap. / Kry jou broekspyp dalk 'n gaatjie. / Mooipraat? Nee, ons ken jou nie. / Weg jou hand en raak ons nie! / "Oppas," het die baas gesê, / "tot ek weer kom, hier bly lê." / Op ons pootjies lê ons kop, / maar ons hou jou darem dop. / Toe-oog slaap ons op die baadjie, / maar ons loer nog deur 'n gaatjie - / een oor plat, en een oor op, / PAS-OP!!

2. Phrases from novels, as well as poems and the titles of various texts used in this article were translated into English by the author, more often a creative version than a direct translation.

3. Die strandjutwolf / Dit kom net met die donker maan: / ek hoor dit vér eers roep / soos iets wat klae in die veld; / dan is dit by die stoep ... / hy snuiwe aan die drumpel saggies / en roer rondom die huis, / ek hoor hom ruik-ruik asemhaal / en krap by die kombuis; / die hele werf is vol van hom: / daar waar die ploeë blink, / daar sien ek die os-groot skadu roer / en hoor iets ysters klink. / Ek weet hy is so grys en groot, / dat as hy regop klim / dan krap sy pote aan die nok, / hy luister by die skoorsteen in ... / en as ek in my kamer lê / en áls is stil en swart, / dan weet ek is dit in die huis, / ek luister na my hart, / ek weet sy oë is vaal en blind, / ek hoor hom sagter as 'n snik / net in die gang, en tussenin / my polshorlosie tik, / en op die helder dag weet ek / dat die Gryse by my bly, / ek hoor sy draffie en ek voel / sy wit oë agter my.

4. Ballade van die bose / Ek is in jou / gevleg, gerank / soos 'n wortel in / in die donker bank, / en van voor die daeraad / se blank begin / straal ek by albei jou oë in [...] / Ek is jou wese/ se ondergrond / en ek trap in jou spoor / soos 'n goeie hond.

5. In die uitgrawing / Hoor hoe stil het dit om ons geword. / Daar snuffel niks meer nie. / Die rumoer is verby, die jammerende tewe, / die milisiehonde verby.

6. Tormentoso I / Mag die nagjut wat geleer het om bedags te jag / jou vind en opruim [...] / Mag jy aas word soos die robbaba [...] / Jy is nie verlore nie. Jy sal in my binnegoed verteer. / Ek is jou strand, jou see, jou jut [... ]

7. Spoor / jy roep - / jy het daardie snaakse blaffie / vog drup uit jou pels / jy het honger / wat ek met my helder strome / nie meer voed nie

8. Tormentoso II / sy skink snags vir haar eensaam wyn / en drink dit met genoeë / sy wandel met die bolpensglas / deur kamers wat haar woning was / en luister na die storm: daar is 'n hond / wat by haar voete hou, verwonderd / oor die wilde vrou / en soms, wanneer die huis se dak wil lig / hou sy die glas omhoog en rig 'n heildronk / aan verwilderdheid: / was dit 'n gril? / want as sy vinnig omdraai, dryf / daar in die spieël 'n wyfiewolf / se heldersiende oë

9. In this section quotations will only be provided in English, except for a few shorter citations where there might be uncertainty about the translation.

10. Drosterhonde bo Oranjesig / Wat sou hulle makeer het, daardie brakke? / om weg te dros uit gawe buurte / waar hulle onder vriendelike dakke / beskerm was teen die winterguurte / - alles gehad het wat 'n hond in sy / eenvoud kan vra? kos in groot bakke / (ten spyte van die lewensduurte), / 'n kaggelvuur om saans voor neer te vly / binne ons dampkring, ons aroma; / haas elke aand met Baas 'n wandeling, / en, as hul siek was, die behandeling / van 'n veearts met 'n diploma! / snuffelpartytjies op straathoeke, / en die uitdagende lapbroeke / wat die afleweringsjong gedra het - / daardie brakke - wat sou hulle gepla het?