Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Tydskrif vir Letterkunde

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9070

versão impressa ISSN 0041-476X

Tydskr. letterkd. vol.55 no.3 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9070/tvl.v.55i3.5503

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Take a bow: Art and dog communication

Wilma Cruise

South African sculptor who focuses on human and animal figures. She has a doctorate in the new field of anthrozoology. Email: wcruise@global.co.zaz

ABSTRACT

Bentham's query "[...] the question is not can they reason? Nor can they talk? But, Can they suffer?" (Bentham 8) drew attention away from language and the interior life of animals and focused it instead on the question of suffering. Just what suffering is left to the human to decide; a debate, which forms a large part of the discourse in the animal rights movement. But what happens if we were to return to the unanswered part of Bentham's quote, the questions that Descartes so famously answered in the negative: "Can they reason?" "Can they talk?" These questions have been banned by scientific and philosophical discourse up until recently when the burgeoning interest in the 'animal question' re-opened the debate. Making the assumption that animals can indeed 'talk' I investigate the nature of dog/human/dog communication using as a conduit the art of South African artists, Elizabeth Gunter, Daniel Naudé and myself. I propose that dog to human and human to dog communication relies on nonverbal means such as bodily semiotics, prosody and other ineffable means that are not dependent on symbolic language.

Keywords: anthropomorphism; art; behaviour; dogs; language

"We have shut our ears to their primal screams, their rumbles, hisses, purrs [...]"

- Wilma Cruise qtd. by B. Schmahmann in the catalogue

Cocks, Asses & ...

"All knowledge, the totality of all questions and all answers, is contained in the dog. If one could but realize this knowledge, if one could but bring it into the light of day. "

- Franz Kafka, "Investigations of a dog" (italics mine)

The context of my research is neither scientific nor philosophical but rather, unusually, artistic. I take my justification from, amongst others, J. M. Coetzee's fictional character Elizabeth Costello, who says that it is via poetics that understanding with the animals might be reached. Her implication is that it is through affect rather than reason that we get closer to the animal other. It can be argued, then, that the largely unconscious means of creation in the studio mimics that of the inchoate communication that takes place between human and the animal other.

Accessing animal minds is a relatively new phenomenon. Based on Descartes' assertion that only humans think and that the animals are mere automata, it was assumed that animals did not have capacity to reason, let alone feel emotion. The separation of human and the (other) animal and the superiority of one above the other is entrenched in the Judeo-Christian system of belief as expressed in God's injunction in Genesis that the (hu)man should "have dominion over the fish of the sea, and the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth" (Genesis 1:28). Arguably the Cartesian, mechanistic view reached its apogee in the behaviourist movement of the mid-twentieth century. Behaviourism was, inter alia, a reaction to the psychoanalytical models of psychology of Freud and Jung specifically claiming that neither the id and the ego, nor the collective unconscious, were identifiable and measurable in empirical terms, and therefore that the effects, even existence, of these entities was in question. Behaviourism had a philosophical underpinning in the theories of logical positivism, and was associated chiefly with philosophers of the Vienna School. Logical positivists rejected the metaphysics of traditional philosophy and based their thinking on pragmatic principles of science and logic. In these terms philosophy's task was "to reduce statements to their empirical components and to verify their truth claims" (Macey 232). In the behaviourist model, animals are biological subjects, subjected to pre-determined stimuli to which they react in predictable and pre-determined ways. What this meant for the study of animals is that the animal is reduced to a responding bio-automaton. This extreme determinist view affirmed the Cartesian view of animal-as-machine.

Does the animal speak? Does it think? What is the nature of its thought? These are the conundrums that the behaviourists refused to face. By raising the spectre of anthropomorphism they drew ever further away from engaging in a meaningful sense with (other) animals. But, as John Berger suggests, in the prescientific age it was precisely anthropomorphism and the projection of imaginative empathy that connected us to the animals and kept us in (empathetic) proximity to them (Berger 252). Jacques Derrida concurs. In his naked encounter with his little cat, he tried imagining the world from her point of view. Thereby engaging with his cat Derrida felt himself looking deep into the eyes of God: "I hear the cat or God ask itself, ask me: Is he going to call me, is he going to address me?" The cat did this without "breathing a word". Deprived of language the animal is rendered mute and in its muteness there is a great sadness. Yet in spite of its silence, its lack of logos, Derrida admits to the possibility that the animal thinks. "The animal looks at us, and we are naked before it. Thinking perhaps begins there" (Derrida 29). Thinking about (the animal's) thinking is the point. It is a leap into the territory banned from the Cartesians' and behaviourists' lexicon.

The encounter with his cat is a key moment in Derrida's exposition of The Animal That Therefore I Am. It is important to note that Derrida did not pose a philosophical question in the vacuum of abstract thought. Instead he based his query on a real experience. His encounter with his little cat was in the bathroom when she saw him naked. She was neither a generic animal nor a generic cat. Derrida's investigation is thus not merely the machinations of a philosopher but a particular autobiographical experience.

No, no, my cat, the cat that looks at me in my bedroom or bathroom, this cat that is perhaps not "my cat" my "pussycat," does not appear here to represent, like an ambassador the immense symbolic responsibility with which our culture has always charged the feline race. If I say, "it is a real cat" that sees me naked, this is in order to mark its unsubstitutable singularity. (9)

But how do we access animals' minds? Faced with Wittgenstein's statement "If a lion could talk, we could not understand him" (qtd. in Wolfe, "In the shadow", 44), we are faced with a seemingly impossible conundrum. It is not only the barrier of symbolic language that we have to scale, but the notion that animals have an epistemic knowledge that is so different from ours that it is virtually unknowable. Further, even if we were to have access to animal minds, our language would be inadequate in dealing with the contents of it. Also, it is entirely possible that animals think in a different format from human natural language, a difference as marked as that between analogue and digital forms (Beck 254).1

Nevertheless, since we do understand a lot of animal communication, Beck suggests we share an evolutionary "core cognition", one that permits cross-species mutuality (Beck 255). That is, we do know what other species think and feel without being sure how, or even precisely what, we know. This notion accords with Elizabeth Costello's idea of sympathetic imagination. Sympathetic imagination is the ability to imagine yourself in the place of the other even if the other is a nonhuman animal. There are no limits, she maintains, to sympathetic imagining. "If I think my way into the existence of a being that never existed, then I can think my way into the existence of a bat or a chimpanzee or an oyster, any being with whom I share the substrate of life" (Coetzee 80).

But what Costello is talking about is still communication from the human transposed and imagined onto the animal. It is a one-way street as it were. Where is the responding living animal in the abstract scenarios that Costello evokes? Donna Haraway draws comparisons between Costello and another of Coetzee's fictional characters, Bev Shaw, the volunteer animal caretaker in Disgrace, whose task is to euthanise condemned dogs. This duty she does with respect and regard for her charges. Haraway says that Costello seems to be locked into the abstractions of her lectures without engaging with actual animals in messy co-entanglements (Haraway 81). But Haraway's accusation might also be a touch unfair. Costello herself objects to the cold reason of the philosophers preferring the company of those who engage with the animals. "[I]f reason is what sets me part from the veal calf, then thank you but no thank you, I'll talk to someone else" (Coetzee 112). Nevertheless, Haraway points towards the necessity of multi-directional relationships between humans and (other) animals. Conceding the asymmetry of such relationships she advocates a response/response-ability, post humanist (non-humanist) way of interacting in which "a relationship is crafted in intra-action through which entities, subjects and objects, come into being. [...] If this structure of material-semiotic relating breaks down or is not permitted to be reborn, then nothing but objectification and oppression remains" (Haraway 71).

Similarily Marc Bekoff, a cognitive ethologist, argues for intra-action between species based on a biocentrically anthropomorphic position (Bekoff, "Wild Justice" 72). What he means by this is that it is necessary to approach animal behaviour from a species' specific point of view. Thus when studying dogs it is necessary to be "dog-o-centrist", chimp-o-centric when studying chimpanzees, and so on. Wendy Woodward terms such stances "relational epistemologies" (Woodward 3). For example, the perception of a cat from a mouse's point of view (a terrifying predator) would be different from that of the human's (a cuddly pet). Beckoff has inter alia studied the evolution of morality in a variety of species particularly those that function in groups. Observing canids at play he has documented the operation of justice and fairness, concepts that can be (anthropomorphically) inferred from a number of discrete behaviour patterns including "the bow".

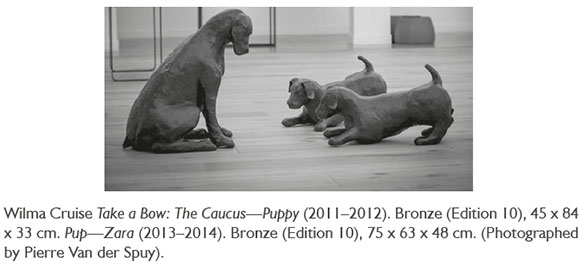

The bow is a frequent behaviour in dog games-a behaviour I captured in my 2014 work Pup Zara (2013-2014) and The Caucus-Puppy (2011-2012). The Caucus-Puppy is based on John Tenniel's original illustration in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

In the book the puppy's playful stance is an exhortation to Alice to join in a game of catch. But Alice has shrunk to a fraction of her normal size. She is terrified of the giant, rambunctious puppy and hides under a thistle bush. In spite of her terror Alice recognizes that the puppy is only doing what puppies are meant to do. "And yet what a dear little puppy it was!" she says while planning her escape (Carroll 46).

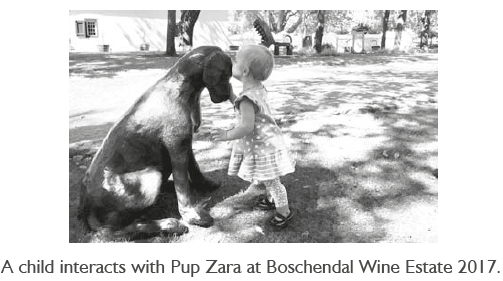

In the sculpture's scenario, the puppies invite the other pup, Zara, to play by assuming the position of a mock bow. Bemused, Zara watches their antics. It is just an instant before she leaps in to join the game-a moment that any observers of dog play will recognize. The placement of the dogs occurred by chance. The sculptures were in fact made some time apart but once put in relational proximity the gap between became a conduit for communication and thereby became the raison d'etre of the works. The dog's behaviour becomes recognized by other dogs but more importantly also becomes recognized by other humans-as is captured in these images of a 14-month-old child responding to what is actually, in reality, two lumps of metal.

Thus if one has to regard language as more than the one spoken by humans the possibility exists of a multiplicity of species languages. Following Bekoff there would be, for example 'Dog' and 'Horse', two languages I am reasonably familiar with. But here is the caveat. Before we can assign language to animals it behooves us to define the term, for the blatant fact remains that logocentric language in all its ability for infinite permutations and abstractions remains a uniquely human phenomenon. Noam Chomsky proposed the concept of an innate human ability for language-a hardwiring of what he calls a Universal Grammar. Basically this claim re-asserts human exceptionalism along the traditional divide of language- humans speak, animals are dumb.2

During the '70s and '80s there were many attempts made to raise chimpanzees with humans, assuming that they would pick up the rudiments of language from the environment. These experiments failed in that chimpanzees did not acquire symbolic language beyond the most basic level and then only through hours of operant conditioning. But what the experimenters chose to ignore was the profound emotional communication that was actually occurring between the apes and their human handlers. There was communication between the species but it was an affective one based on bodily semiotics. Language was being spoken but not the logocentric one that the experimenters focused on. It was a wordless transaction of profound emotion.

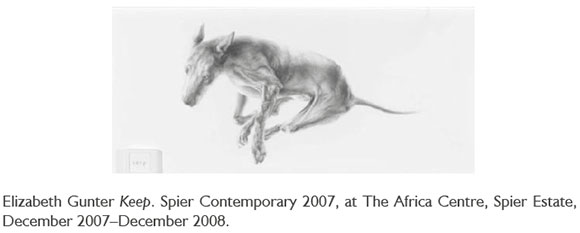

This tension between word and wordlessness is expressed in a series of drawings of dogs entitled "Keep" by the South African artist Elizabeth Gunter. Gunter explores the boundaries of language in relationship to animals.

She recalls that as a child she imagined herself as a small animal without knowledge of self. She had been told by her father that animals were without speech, reason or self-awareness. Projecting herself into an animal lost in the world, and lost to the world, was strangely comforting.

I [...] became aware of a wordless centre, a muteness that is not without meaning. It is that muteness that I try to mark, because to my mind it is where I find mutuality with animals, or where I feel my own animality. Some idea of what non-human animals feel like-the same as what I feel/experience when I draw: mute meaning. (Gunter n. p.)

Through the act of drawing she is able to achieve a sympathetic if not empathetic identification with the animal. She says:

Keep attempts to portray a collective desire for engaged membership and equality by means of silent yet playful gesture. The dog and its body language are chosen as symbolic of a singular and often misread or inadequate means of communication with humans, and to emphasise its wordlessness and insularity. This wordlessness is contrasted with written words, communicating commands that would, if submitted to, result in total disempowerment or disablement of the very energy and exuberant gestures of the dogs. (Gunter qtd. in Pather, n. p.)

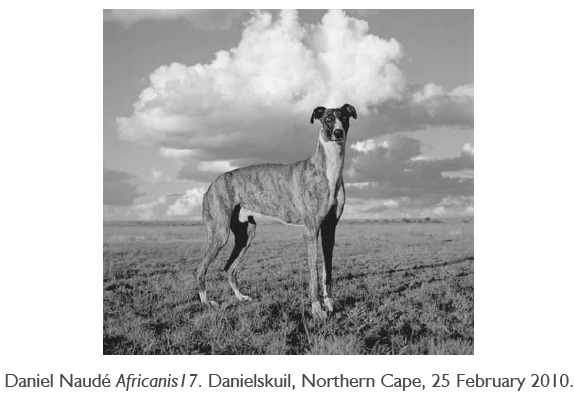

This willingness to engage the animal qua animal in its full specificity and singularity is echoed in the work of the South African photographer Daniel Naudé.

He creates images of feral dogs in a way that focuses as much on the animal being as on the human on the other side of the gaze. The impetus for his collection of animal photographs in Animal Farm (Naudé 9) was inspired by the look of a feral Africanis dog, which for "a split second looked back at him" before slinking off leaving him "speechless and full of emotion".

The intensity of that shared glimpse made Naudé determined to depict the dogs in a way that captured their presence and their experience (Naudé 7). Like Der-rida's cat, Naudé's dog was singular and particular to that moment. What exactly was communicated during that fleeting exchange, however, remains "unfathomable, unexplained and yet incredibly potent" (Naudé 9). Naudé has identified the problematic of the space-between the human and animal gaze, which implies the key question of what happens in this space. Broglio identifies this space as "the contact zone" (xxiii). What is communicated? Who is this being doing the communicating? Echoing Naudé's report of the unfathomability of the exchange between human and animal, he says that "the human-animal contact zone becomes a contact without contact, a relation of nonrelations and communication whose language would be under erasure" (Broglio xxiv).

Moving from a humanist position to one that encompasses other animals suggests other ways of thinking of animal languages. One such idea is to abandon the model of anthropocentric symbolic language against which other animal languages are tested. In this context, Carl Safina has proposed the concept of "prosody" (202). Prosody-the patterns of rhythm and sound used in poetry-constitutes paralinguistic features of song, tempo and tone, which convey meaning without words. While a dog is incapable of using words, it is nevertheless able to communicate via bodily semiotics and sounds which, crossing species' barriers, human beings are able to understand. For example, we are able to interpret our dog's whine even though we are not a dog. We know that a growl means something different from a bark; and that a cat's hiss differs from her purr. It is not, as the Cheshire cat suggests, "madness" that we know the difference between a dog growling when he is angry, and wagging his tail when it is pleased, and the cat growling when she is pleased and wagging her tail when she is angry (Carroll 64). We are quite capable of interpreting such situations correctly and acting upon them in the appropriate manner. Prosody enables us to distinguish a lullaby from a scream in humans, or a short upward call indicating alarm from a soothing downward one in other animals. That is, sound, without words, carries emotion and meaning and notably this occurs across species. Prosody links us to other animals. It might be that which re-establishes the sacred connection to other animals.

Yet, hampered by the fear of anthropomorphism, researchers are reluctant to translate these sounds. With reference to Joyce Poole's work with the African elephant, Carl Safina notes that while Poole takes meticulous recordings of the elephants' vocalisations, using measurable scientific means such as the frequency and amplitude of the sounds, other than noting the context in which they are made, she fails to interpret their vocalisations. She does not translate from elephants' language to human language. In this way her experimental methodology, and others like it, does not reach beyond description. In other words, we know that the animals are communicating, but not what they are saying. Safina accuses these researchers of ignoring the obvious: "At its simplest if the animal behaves joyously in a joyous situation, it would be the most uncomplicated and direct to interpret the emotion of joy" (29). Our inability, or refusal, to translate renders us tone deaf to their utterances.

Do other animals have a consciousness of themselves as separate individuals? If animals do have what has been termed "a theory of mind", the next logical question is how do we identify it? One such means is the mirror self-recognition test (MSR), developed by Gordon Gallup in 1970. An animal is marked on a part of its body with ink. If the animal on viewing itself in a mirror tries to wipe the spot off its own body, it is said to demonstrate self-recognition. Gallup argues that this is evidence of self-concept (qtd. in Wynne and Udell 190). The number of species that pass the mirror self-recognition test is quite limited and seems to be confined to the great apes. It excludes dogs. Does one then conclude that dogs do not have self-recognition? This deduction is challenged by amongst others, Marc Bekoff, who in his classical "yellow snow" experiment, demonstrated that dogs have self-recognition based on a sense of smell. After compiling and statistically analysing the data, Bekoff found that Jethro, his own dog and the subject of the experiment, paid significantly less attention to his own displaced urine than he did to the displaced urine of other dogs. In his paper "Observations of scent-marking and discriminating self from others by a domestic dog", Bekoff did not specifically claim that this proves that dogs have self-awareness, but the question is raised as to whether there is a fundamental difference between an animal recognising its own image in a mirror and one recognising its own scent in yellow snow? As dogs prioritise smell above vision, it is entirely logical that they would ignore the visual cues in the mirror when not accompanied by identifying smells. Smell and sight involve different cognitive processes. Bekoff himself has suggested that the yellow snow test may be more indicative of a sense of "mine-ness" in dogs than of a sense of "I-ness". In his discussion of Beckoff's paper Norris (n. p.) offers a critique of MSR experiments and those like it: "At a minimum [...] the yellow snow test stands as a useful warning that we humans need to be careful not to make quick judgments about animal intelligence or cognitive capacity (or lack thereof) based on tests that are well-suited to humans, but that fail to match the skills and abilities of the particular animal."

Emotion and affect can be the primary means of communication between human and the other animal, one that I suggest cuts across species and allows for mutuality. Openness to other means of communication opposes reason with what Elizabeth Costello calls "fullness" and "the sensation of being" (Coetzee 78) suggesting that communication with other animals it is through the body-the semiotics of the body along with its primal sounds-gestures and noises that link us all together as animal-kind. Ron Broglio offers the intriguing suggestion that it is (contemporary) artists rather than philosophers who are likely to offer new insights into the question of the animal. As philosophy is delimited by language and reason "(including the limits of reason)", artists are able to address the question free from rational constraints in a material and engaged way. This is achieved not in the sense of:

[...] mimesis or representing animals in a natural history tradition or kitsch assimilation of animals into our world as tamed or cute or defeated; rather these artists have unmoored themselves, even ever so slightly, from the cultural grounding of meaning and the solidification of being over becoming [...] (Broglio xx).

The artistic process that is achieved through the manipulation of material and intuition mimics the encounters between human and the other animals thereby opening the way for new modes of thought and new possibilities for thinking about the animal other (Broglio xxi).

WORKS CITED

Beck, J. "Why we can't say what animals think." Philosophical Psychology vol. 26, 2013, pp. 520-46. [ Links ]

Bekoff, M. "Wild justice and fair play: cooperation, forgiveness and morality in animals." The Animals Reader. Eds. L. Kalof & A. Fitzgerald. Berg, 2007, pp. 72-90. [ Links ]

Bentham, J. "Principles of Morals and Legislation." The Animals Reader. Eds. L. Kalof & A. Fitzgerald. Berg, 2007, pp. 8-9. [ Links ]

Berger, J. "Why look at animals?" The Animals Reader. Eds. L. Kalof & A. Fitzgerald. Berg, 2007, pp. 252-61. [ Links ]

Broglio, R. Surface Encounters: Thinking with Animals and Art. U of Minnesota P, 2011. [ Links ]

Carroll, L. The Complete Illustrated Works of Lewis Carroll. Chancellor, 1982. [ Links ]

Coetzee, J. M. The Lives of Animals. Princeton U P, 1999. [ Links ]

Derrida, J. The Animal that Therefore I am (more to follow). Trans. J. Wills. Fordham U P, 2008. [ Links ]

Gunter, E. Personal correspondence and interview. May 2016, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. When species meet. U of Minnesota P, 2008. [ Links ]

Kafka, F. "Investigations of a Dog." Trans. P. Strazny. Kindle edition. <www.amazon.com/Investigations-Dog-Franz-Kafka-ebook/dp/B01N09B8R5> [ Links ].

Kalof, L. & A. Fitzgerald. The Aminals Reader. Berg, 2007. [ Links ]

Macey, D. The Penguin Dictionary of Critical Theory. Penguin, 2000. [ Links ]

Naudé, D. Animal Farm. Prestel, 2012. [ Links ]

Norris, P. F. "The 'Yellow Snow' Test for Self-Recognition." AnimalWise. 16 Aug. 2011. <https://animalwise.org/2011/08/16/the-yellow-snow-test-for-self-recognition/>. Accessed 16 Oct. 2017. [ Links ]

Pather, J., ed. Catalogue for Spier Contemporary 2007 Exhibition. Africa Centre, 2007. [ Links ]

Safina, C. Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel. Kindle edition. Henry Holt and Company, 2015. <https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Words-What-Animals-Think-ebook/dp/B00RMU8/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=> [ Links ].

Schmahmann, B. Cocks, Asses & ... Catalogue for an exhibition held at the University of Johannesburg, 7-28 November 2007. David Krut, 2007. [ Links ]

Wolfe, C. "In the shadow of Wittgenstein's Lion: Language, ethics and the question of the animal." Animal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species and Posthumanist Theory. Ed. C. Wolfe. Chicago U P, 2003, pp. 44-94. [ Links ]

Woodward, W. The Animal Gaze: Animal Subjectivities in Southern African Narratives. Wits U P, 2008. [ Links ]

Wynne, C. D. L. & Udell, M. A. R. Animal Cognition: Evolution, Behaviour & Cognition. 2nd ed. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. [ Links ]

1. Beck uses the analogue/digital opposition to emphasise his point that animals' thinking processes are markedly different from the logos of dependent human practices.

2. It is important to note that Chomsky, Hauser et al. later changed their minds about the uniqueness of human language, arguing for a much stronger continuity between animals and humans with respect to speech than previously believed (Haraway 235).