Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Tydskrif vir Letterkunde

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9070

versión impresa ISSN 0041-476X

Tydskr. letterkd. vol.51 no.2 Pretoria sep. 2014

Looking forward towards peace by remembering the past: Recycling war and lived histories in contemporary Mozambican art

Amy Schwartzott

Lectures in Non-Western Art History at Coastal Carolina University, Conway, South Carolina, USA. Email: aschwartz@coastal.edu; zott@ufl.edu

ABSTRACT

Contemporary Mozambican artists who use detritus as media create artworks that chronicle their culture through bits and pieces of its discarded histories. By using culturally specific and symbolically charged recyclia, these artists create art that is quintessentially Mozambican, as the materials they use become potent signifiers of Mozambique. Contemporary artists' use of recycling, in particular the recycling of weapons in the Transforming Arms into Plowshares/Transformação de Armas em Enxadas(TAE) project allows recycling to emerge as a paradigm in contemporary African art, and as a potent tool for cultural investigation. Utilizing recycling as a tool develops a broad, cross-cultural, interdisciplinary framework to investigate complex issues within divergent African and global societies. Artists in Mozambique who recycle are not only connected to cultural and artistic practices of the past, they continue these traditions within contemporary contexts. By creating artwork from cast-off materials, artists who utilize unwanted debris in Mozambique illustrate how recycling permeates all levels of society, including its broad expansion into art making, and how the use of reprocessed materials by artists both inspires and instills a sense of pride in artistic practices.

Keywords: : detritus as artworks, Mozambican art, recycling, Transforming Arms into Plowshares/Transformação de Armas em Enxadas(TAE).

Contemporary Mozambican artists who use detritus as media create artworks that chronicle their culture through bits and pieces of its discarded histories. By using culturally specific and symbolically charged recyclia, these artists create art that is quintessentially Mozambican, as the materials they use become potent signifiers of Mozambique. Several artists equate their artwork with distant lives and cultural remnants, linking their contemporary art with past narratives and commemorated identities.

I have been investigating contemporary African artists' use of recycling materials as media since 2007. Beginning in Senegal, I have been developing my understanding of recycling as a paradigm in contemporary African art, and its potency as a tool for cultural investigation. Utilizing recycling as a tool develops a broad, cross-cultural, interdisciplinary framework to investigate complex issues within divergent African and global societies. Working in Mozambique intermittently since 2008, my longest uninterrupted tenure included fifteen months of fieldwork, which I completed in Mozambique in 2010-11, with funding from a Fulbright-Hays DDRA grant. This research has enriched, solidified and broadened my engagement with contemporary African art as well as providing fertile research foundations.

While artists in Mozambique utilize many different types of media, I have discovered that a majority of artists choose to work with pre-used materials. My investigation is founded on a series of interrelated themes and concepts that are difficult to unwind. These connected ideas include object materiality, recycling, art making in urban Africa, and post-conflict resolution. Artists in Mozambique who recycle are not only connected to cultural and artistic practices of the past, they continue these traditions within contemporary contexts. By creating artwork from cast-off materials, artists who utilize unwanted debris in Mozambique illustrate how recycling permeates all levels of society, including its broad expansion into art making, and how the use of reprocessed materials by artists both inspires and instills a sense of pride in artistic practices.

Many creative, environmental, and financial factors-including the impact of past wars, and the subsequent development of the Transforming Arms into Plowshares/ Transformação de Armas em Enxadas (TAE) project-illustrate how recyclia provides an advantageous art medium. Because of Mozambique's protracted history of warfare, the TAE project was established as a peacekeeping tool to heal, memorialize, and prevent further wars through the promotion of peace by collecting and destroying left over artillery. This project, described more fully below, serves as an impetus for catharsis, grieving past violence and deaths resultant of past Mozambican wars. The project has had an unexpectedly fortuitous result in its significant contribution to the growth and ensuing popularity of recycling as an artistic practice in Mozambique. I would like to focus on the importance of this influence, as well as briefly summarizing other creative, environmental, and financial factors that have contributed to a widespread use of recycled materials as media by contemporary Mozambican artists.

The Mozambican "civil" war (1976/7-92), almost directly followed the nation's battle for independence from Portuguese colonial rule (1961-75). Due to the complexities of this conflict and the fact that both sides received considerable external support, referring to this war as "civil" is widely contested among scholars, and it is often referred to as Mozambique's post-independence war. This war was fought between the ruling party, Frente de Liberação de Mocambique (Frelimo, The Liberation Front of Mozambique), founded in Tanzania in 1962 to fight for the independence of Mozambique, and the Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (Renamo, Mozambican National Resistance). Renamo was founded in 1975 following Mozambique's independence as an anti-Communist resistance movement.

Whereas scholars debate the extent to which external aggressors initiated Mozambique's last war, the larger point of importance most central to this investigation is the aggregate damage, violence, and overall destruction caused by this conflict. Social anthropologist Bjørn Bertelsen, who focuses on Mozambique and Southern Africa, succinctly captures the totality of the powerful impact of violence on Mozambican culture following its wars: "sketches of colonialism and post-independence civil war in a country in which relations between state and violence, however one might conceive of these entities, have been crucial, visible, and tangible from the liberation struggle onward" (Bertelsen 216). Mozambique's post-independence conflict precipitated economic collapse, famine, nearly one million war-related casualties, and the internal and external displacement of several million civilians.

Past wars and the TAE project have dramatically inspired a definitive Mozambican style of art characterized by its pervasive medium of pre-used materials, and its primary technique of recycling. The TAE project developed by Bishop Dom Dinis Sengulane as a mechanism for peacebuilding, peacekeeping, and post-conflict resolution, has made a great artistic contribution, as an impetus and didactic force by introducing artists to recycled materials as media to create art, beyond its aim to remove weapons from the landscape of Mozambique. Furthermore, The TAE project reveals the potency of recycling as an artistic tool in post-conflict resolution. Bishop Sengulane, who retired in March 2014 after nearly 40 years of service as Mozambican Anglican Bishop, founded the TAE project in 1995. TAE originated in the context of workshops within the aegis of non-governmental organization Conselho Cristão de Moçambique (CCM, Christian Council of Mozambique's) project, aimed at establishing peace and democracy following Frelimo/Renamo negotiations and the General Peace Agreement signed in Rome in 1992 (Sengulane interview).

Bishop Sengulane initially viewed TAE as a tripartite process: it consisted of collecting weapons, making them non-usable, and providing an instrument of production as an incentive in exchange for the collected weapons. Following TAE's establishment, it has provided incentives to individuals referred to as "informants," who hand over guns and other military hardware to the organization in order for the weapons to be destroyed. Artists have participated in the TAE project and transformed destroyed weapons of war into memorial sculptures since Bishop Sengulane first introduced an art component to TAE in 1997 at A Associagão Núcleo de Arte. TAE's transformative process is inextricably linked to Mozambican wars, aiming to eradicate weapons left behind following these wars and provide efforts to achieve memorialization, post-conflict resolution, and to promote peace.

My research on TAE contextualizes the materiality of the weapons transformed by artists and the crucial fact that these artistic media were originally artifacts of Mozambique's extended conflicts. TAE artists use recyclia both literally and conceptually, creating evocative art while deconstructing Mozambican history. TAE's transformative process utilizes past histories of recycled materials to inscribe meaning as these objects are transformed into art. TAE's purposeful destruction and transformation of recycled weapons of wars enables these arms to make visible the invisible concept of peace- through the compelling symbolism of artworks composed of former tools of killing. The sublime visual power of TAE artworks engages viewers to remember the violence and destruction of war and strive for this never to happen again.

The theoretical framework for investigating recyclia as media draws largely from social anthropology and visual culture studies, specifically the writings of Igor Kopytoff and Nicholas Mirzoeff. Kopytoff's seminal essay, "The Cultural Biography of Things," focuses on an object's transformation from its initial use through its many lives. Centrally, I argue that the life of an object (such as a weapon) does not end when it is decommissioned, destroyed, and recreated artistically. Rather, in its reincarnation as a recycled material it gains more expressive power as it is transformed into art. I focus on how Kopytoff's emphasis on the object is rooted in the importance he gives to its original identity and how this intrinsic meaning is maintained. Whereas TAE physically cuts weapons to prevent their further use, the recognizable shapes of the parts of the guns remain, reminding viewers of their original identity, or history of the object. The iconic symbolism of the weapons as they are transformed is essential for understanding the meaning of the TAE arts.

Mirzoeff's assertion of "the visual as everyday life" (76), informs this exploration, by linking how daily recycling extends to the practice of art making, through the widespread use of recycled materials in the creation of contemporary art in Mozambique. Artists who transform tools of destruction into tools for peace are also recycling objects into art. Artist Titos Mabota made an astute observation during one of our conversations about the TAE project and its popularity among artists. He explained that a major appeal of the project is its provision of materials (Mabota interview).

Artists who work with TAE gain access to materials at no cost, as well as learning about the advantages of choosing recyclia as a medium. In addition to the project's important message of peace, by taking part in TAE, artists receive first hand experience working with recycled materials. TAE has made a great impact in the artistic community of Maputo particularly, where its headquarters is based. Because of its influence, artists have become engaged with a project promoting peace that also inspires them to seek pre-used materials in their art making practices.

Since collaborating with TAE, many artists have been inspired to work with diverse recycled materials, as well as engaging in varied techniques, which include unraveling canvas, tearing newspapers, and stitching together bottle caps. Other methods comprise welding destroyed weapons, gouging boat hulls, carving dead trees, and pounding pots and pans. Each of these different techniques facilitates the transformation of recycled materials into art.

Object materiality has been a fundamental focus of my investigation, as it elucidates the selection of specific media used by artists. This inquiry develops a greater understanding of artists' conceptual methodologies, and individual styles. My analysis of the use of diverse recyclia by artists remains strongly rooted in Igor Kopytoff's "Cultural Biography of Things," which inspired my subsequent inquiry into the history of the objects and the artists who use them. Regardless of whether the object is significantly altered in its adaption to become part of an artwork, each of these objects become disengaged from their past uses.

Recently, fear of war between Frelimo and Renamo in Mozambique has been exacerbated by the latter's unilateral annulment of its 1992 Peace Accord with Frelimo on October 22, 2013. Renamo's actions are a response to Frelimo's attack and seizure of its military base in Santunjira, near Gorongosa in the Sofala province. Daily accounts by national and international news agencies report continuing violence between Frelimo and Renamo. Armed attacks have escalated since fall of 2013, resulting in loss of life on both sides of the conflict.

Increasing tensions between Frelimo and Renamo indicate the return to war as a real possibility. Looking beyond the terror of recent events in Mozambique, it is necessary to recognize an important concept that resonates through this uncertainty: War continues to influence the lives of Mozambican artists and is manifested through their artistic expressions. A new sculpture by Jorge José Munguambe (Makolwa), o medo de voltar a guerra ("The fear of returning to war"), is a vivid commentary on the precarious situation in his country at the present time (see figure 1).

Constructed of recycled materials, the work combines a pan with plastic handles, kettle, the inner part of a spotlight, copper and aluminum wire, and nails. Makolwa in personal communication, described the sculpture, explaining how it expresses his fears that his country may soon return to war:

I fear that I have to go back to war (me and the remaining young Mozambicans) because of the political situation in the country we live-Mozambique and the world, between Renamo and Frelimo, because war is something that has to exist in the world. War leaves the poor without knowing what will happen and leaves the children with no future. I hate people who make war, especially those who make weapons.

Makolwa's sculpture portrays a young, helpless individual who is especially vulnerable to the threat of impending war. The dull, dented surface combined with the wiry, stringy hair, and placid expression on its upturned face reveals inconsolable sadness. The combination of Makolwa's artwork with his narrative defining his fear of renewed war is powerful. Together they underscore the continuing impact of war and its importance among Mozambicans.

Makolwa's sculpture is a watershed artwork, because it directly illustrates the influence of past wars and the TAE project on contemporary artists. Furthermore, this work underscores the move from recycling weapons of war under TAE's influence, to personal selections of distinct and varied recyclia that define individual artistic practices. TAE was influential in defining Makolwa's use of recycled materials as media in his art making. He became affiliated with TAE in 2001 when he first began creating art that promoted peace from recycled weapons of war.

While many TAE artists struggled though the war with families that were torn apart by members aligned with both Frelimo and Renamo memberships, Makolwa's personal connection to TAE differs. His family sent him out of the country to improve his chances to survive the war as a young man. He left his country in 1986 and spent seven years living in apartheid-era South Africa. Makolwa became a shoemaker while in South Africa in order to make money to live (Makolwa interview). He subsequently returned to Mozambique in 1993 following the end of the war. Makolwa's motivations to create art for TAE, as well as the desire to create art from recycled materials in general, are intrinsically linked to his connections to his country:

I began making art primarily to deal with my responses to the civil war. At this time I was creating art for myself as a means of catharsis. I started to realize this was also something I could do to give back to my country-an act of creation to counter the destruction that had taken place. As I realized that my art provided something for people other than myself, I knew that I could offer a visual means to share my experiences and emotions with others. (Makolwa interview)

Beyond producing art from weapons recycled from the wars that ravaged Mozambique, artists have a wide range of motivations for using recycled materials, which include economic, ecological, and creative concerns. Most artists I have observed cite the possibility of expanding their creativity as their foremost impetus for selecting recycled materials as media. Artists' accounts of how they are able to develop creatively by using recyclia are linked to the diversity of materials they select. I would like to provide a brief overview of the varied materials, techniques, and aims of a sample of artists with whom I have worked in Mozambique that illustrates the widespread use of recyclia as media that defines a particularly Mozambican style of art.

These artists include Domingos W. Comiche Mabongo (Domingos), who uses recycled materials as a didactic tool to instruct viewers on widely varied social issues such as recycling practices, the dangers of drinking and driving, and public protests. Domingos is currently working on an artwork titled Manifestação. He will recycle objects he has collected-remnants of social unrest-specifically, riot gear, including incapacitating agents such as aerosols, grenades, bullet casings and cartridges from guns and grenade dischargers. These objects are discarded remnants of tools used by Mozambican police and armed forces. They were used to quell public demonstrations during what is popularly referred to as the Manifestação ("Demonstrations" or "Bread Riots"). These events took place for three days in early September 2010, when public protests broke out in response to government proposals to raise utility prices. Many people were injured and some deaths resulted from the ensuing events connected with these protests. The demonstrations during the Bread Riots effectively shut down Mozambique's capital city of Maputo. By utilizing recycled materials discarded by police to maintain order, Domingos will make a bold commentary on social issues specific to Mozambique, by utilizing the very same elements that were used to maintain public order in the construction of his art.

Mussagy Narane Talaquichand (Falcão) stitches together twisted and tied bits of canvas to create his "modern stitched canvases," as a solution to his lack of canvases for painting. In these artworks, Falcão physically expands the limited surface area of canvas scraps he has access to, as well as dynamically altering the customary single surface of an artist's canvas. Falcão described how the development of his stitched paintings was due to necessity, "I had no canvas. I had to paint-so I started to join scraps. I used the waste of canvas. I sewed it and I connected it." (Falcão correspondence) The canvases Falcão creates are not merely cobbled together; they create multiple surfaces on which he portrays vivid imagery that incorporates figures within a cityscape that populate his urban environments. In these paintings, Falcão creates imagery that captures the "day to day of the Mozambican population, the everyday life of people in Mozambique." (Falcão correspondence)

Zeferino Chicuamba (Zeferino), bases his creation of pots and pans with individual expressions on traditional Makonde masking traditions. Zeferino explained the origins of his artistic development of these pots, establishing their connections to Mozambican Makonde masks:

For me I use faces more because of their connection to masks. [I want to] show- identify-that they are like Makonde masks. The thing that I'm using [to create these faces are recycled pots and pans]-we have to take care of the environment. I'm recycling. I'm using for the face the characteristics that [the] material has- [that] determines the form it takes. (Zeferino interview)

Zeferino's connection between his recycled cookware faces and Makonde masks becomes increasingly apparent after scrutinizing the various physiognomies he creates. In the same way, Makonde masks display diverse expressive and individualized features, some of which include human hair. Makonde masks are distinct among African masks because of the uniqueness among them. The many diverse pots in varied states of disrepair, discoloration, torn surfaces, and blackened edges, reveal the many different personalities Zeferino has given these faces. Each of the unique identities Zeferino creates with these pots has been directly inspired by the materiality of its form. As Zeferino asserts, he relies upon the characteristics of the pot to determine how it becomes transformed into a face.

Nelson Augusto Carlos Ferreira (Pekiwa) selects damaged boats to define cultural histories and social issues of Mozambican fisherman; Intrinsically, Pekiwa maintains the materiality of the form's original use, or history of the objects in the creation of his artworks as he integrates his designs to their recognizable forms (see figure 2, Sem Titulo, ["Untitled"]).

In order to provide a context, he focuses on connections to the social aspects of these materials. Pekiwa commented on these ideas:

I'm enjoying materials that were used before-domestic objects-materials that have some story. When I'm working with these pieces I'm not going to give up its meaning from before. So I respect the meaning, and its functions. But if I transform it, I keep its meaning-I give the art texture [...] Well even now I try to preserve [its meaning] because it has a social context. This is why it's important for me is to try to preserve the object. (Pekiwa interview)

Each of the wooden materials Pekiwa obtains to recycle into his art becomes associated with their former uses, creating a connection between these objects and a social history of Mozambique.

Ana Vilankulos (Matswa) uses capulanas to identify gender in connection with Mozambican identity. Capulanas are brightly colored machine produced fabrics with bold designs, typically cut in lengths measuring six feet by three feet. Similar to African printed fabrics including Kanga, Chitenge/Kitenge, and Dutch Wax Cloths, they are primarily worn as wrappers by Mozambican women and used to secure babies to their mother's backs. Matswa explained her preference for using capulanas and the specific appeal these Mozambican cloths held for her:

I am interested in showing the different things they [capulanas] are used for, we can do more things [with them], not just to carry babies and cover our bodies-[these are] gender connections. It is traditional woman's wear. As you know, capulanas are used for different purposes-to use them for an art piece is to use them in a different form. The capulana is a symbol of an African lady-a Mozambican lady. It reminds me of my mother because she wears capulanas. From when I was young our mothers used to carry us in capulanas, cover us. When you reach five years old, your first present is a capulana. We grew up giving capulanas as presents to our mothers. If you get married it is a symbol. The capulana is a symbol of the progression of life. The story of the capulana means so many things: lady of today, yesterday, and future lady. (Matswa interview)

Matswa continued, defining the role capulanas play in her art, "I am someone explaining to them [viewers] the story of capulanas. I remind them of the story if they don't know how to see capulanas. I don't know if they know the meaning-it is my story." (Matswa interview)

She uses capulanas symbolically as a didactic tool in her art. She expands the diversity of their uses while instructing viewers about their meaning related to Mozambican identities, as she focuses on this particular boldly printed cloth's implicit gender connections.

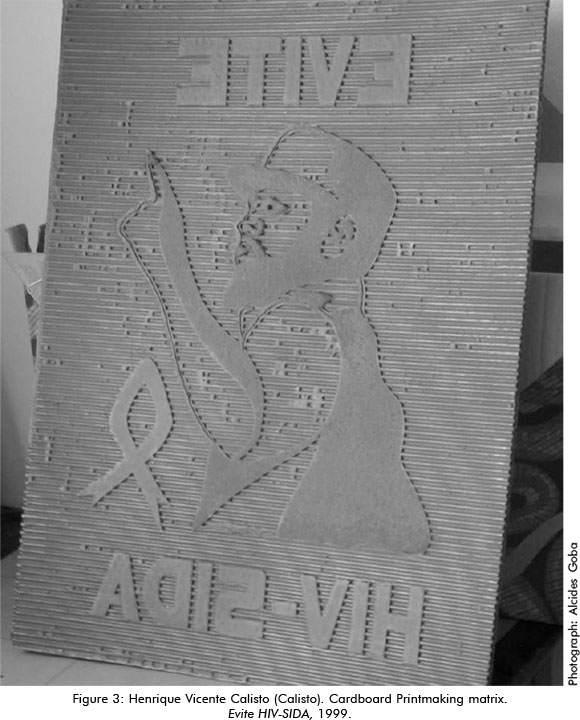

Henrique Vicente Calisto (Calisto) appropriates Mozambican political heroes such as Eduardo Mondlane and Samora Machel in his graphic designs for posters promoting varied social causes such as HIV-AIDS awareness and preventing public urination (see figure 3, Evite HIV-SIDA ["Avoid HIV-AIDS"]).

Calisto chooses to use pizza boxes as printmaking templates because "recycled materials allow more flexibility and force us to open our minds." (Calisto interview) Calisto's art is largely dependent on the recycled cardboard he uses as a tool in his printmaking. He uses cardboard as a matrix, replacing standard supports of silk, metal, or woodblocks to create prints. He explained how he obtains his materials: "I go to the community-like barracas [small shanty bars/restaurants] and to the garbage. I use pizza boxes to create a printing plate. People save pizza boxes for me, such as my sister." (Calisto interview) Calisto is distinct among artists I have interviewed because he utilizes cardboard as a tool for producing multiple artworks, while other artists use recyclia as media to be included within a single artwork. He creates a twist on the use of recycled materials as merely part of an artwork, as he relies on cardboard to develop several new artworks.

Each of the artists discussed here purposely selects pre-used materials as media in the creation of their artwork. Whether they select riot gear, pots and pans, canvas, boats, capulanas, or cardboard, these artists consider the importance of the materiality and/or history of objects' past lives in the inclusion of their art. By choosing materials that relate to specifically Mozambican identities and histories, these artworks tell stories about their makers and their culture. Art making has become a site of expansion of recycling in Mozambican contemporary art, recalling theoretical connections to Kopytoff's history of the objects "life," and Mirzoeff's focus on the everyday aspect of visual culture.

In this research I have linked a number of artists based on their use of pre-used materials, disparate motivations, and proposed outcomes for their artworks. Because of these connections, I believe I have been observing the development and diffusion of a contemporary art historical movement in Mozambique. This movement of artists using recycled materials has evolved and continues to attract artists based on the broad scale of its popularity. Furthermore, the widespread use of recycled materials as media is supported, exhibited, and disseminated by the discursive spaces of contemporary art in Maputo.

Through the presentation of diverse artists I have identified links that illustrate how their art may be defined as distinctly Mozambican. Not only are artists using objects from Mozambican society in their art (perhaps best exemplified by TAE's art made from weapons), but this art also focuses on defining a particularly Mozambican identity based both on its media and its themes indigenous to Mozambique. Recently I received an email from the artist Domingos. I include it here because it underscores the current situation in Mozambique and it makes an important statement about its artists:

Are you all right? Here we are in a state of planning due to the confrontations of the army with the forces of RENAMO in the center of the country, particularly in Sofala. This stems from the stalemate in conversations there have been between FRELIMO and RENAMO and the result of the arrogance President Guebuza finds with the RENAMO leader Afonso Dhlakama. However life goes on and as artists we continue to produce our artwork. Good night. (Domingos personal correspondence)

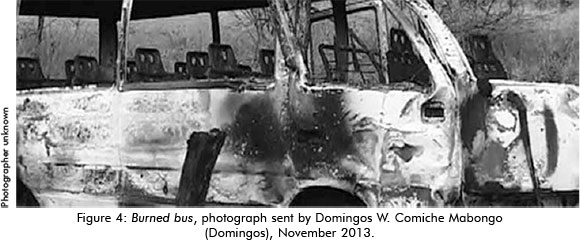

Domingos's email included an image of the shell of a bus that was charred black and destroyed (see figure 4).

This bus represents one of the many attacks that have occurred as a result of the escalating violence between Renamo and Frelimo. This incident and others like it occurred on the main north-south highway between the Save River and the town of Muxungue in the central province of Sofala, roughly 380 miles (about 610 km) from Maputo. Due to this violence, armed military convoys have been necessary to ensure safe passage through this section of the highway (Noticias 2013).

In this case, Renamo gunmen stopped the bus, looted its passengers, killed the driver, and injured nine others (four seriously), and then set bus on fire. Supposedly the bus had been traveling without escorts (Noticias 2013; BBC News 2013). Linking the image with Domingos's words creates a frightening idea of what life must be like now in Mozambique. After receiving Domingos's email I had conflicted emotions. Despite feeling saddened, upset, and helpless about Mozambique's unknown future, I was moved by the poignancy of the fact that he believes life will go on and artists will continue to create art. I hope this is true and the artists and others will remain safe. The artists addressed here as well as many others tell the stories of their culture by transforming recycled mementos of their country's lived histories into artworks. One of the most important ideas these artists continue to demonstrate through their words and art is their ability to recognize the tremendous power of art and its ability to perpetuate inspired acts of creation.

Acknowledgements

I must thank Kathleen Sheldon and Bj0rn Bertelsen for pointing out the necessity of drawing attention to subtle complexities lost with the often over-simplified terms used to describe the history of Mozambique's conflicts. This also includes determining when the wars actually began, as some scholars state as early as 1974, with Mozambican associations with Rhodesia and South Africa. Thanks also to Bertelsen for sharing the scholarship of those who directly address this issue, notably Alpers, Dinerman, Mateus, Nwafor, and Opello.

Works Cited

Adams, Monni. "African Visual Arts from an Art Historical Perspective." African Studies Review 32.2 (1989): 55-103. [ Links ]

Alpers, Edward. "The Struggle for Socialism in Mozambique, 1960-1979." Socialism in Sub-Saharan Africa. A New Assessment. Ed. Carl G. Rosberg and Thomas M. Callaghy, Berkeley: U of California P 1979. 267-95. [ Links ]

Ben Amos, Paula. "African Arts: A Social Perspective." African Studies Review 32.1 (1989): 11-53. [ Links ]

Bertelsen, Bjørn Enge. "Sorcery and Death Squads. Transformations of State, Sovereignty, and Violence in Postcolonial Mozambique." Crisis of the State: War and Social Upheaval. Eds. Bruce Kapferer and Bjørn Enge Bertelsen. New York: Berghahn Books, 2009. 210-40. [ Links ]

"RENAMO attacks in Mozambique," 22 Oct. 2013 BBC News online. 24 Oct. 2013. <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-24625718> [ Links ].

Calisto, Henrique Vicente, interview with Amy Schwartzott, Maputo, Mozambique, February 15, 2011. [ Links ]

Chabal, Patrick. "The Curse of War in Angola and Mozambique: Lusophone African Decolonization in Historical Perspective." Africa Insight 22.1 (1996): 223-87. [ Links ]

Coote, Jeremy. Transformations: The Art of Recycling. Oxford: Pitt Rivers Museum, 2000. [ Links ]

Dinerman, Alice. Revolution, Counter-Revolution and Revisionism in Postcolonial Africa: the Case of Mozambique, 1975-1994. London: Routledge, 2006. [ Links ]

Domingos, (Domingos W. Comiche Mabongo) personal correspondence with with Amy Schwartzott, November 1, 2013. [ Links ]

Doris, David. Vigilant Things: On Thieves, Yoruba Anti-Aesthetics, and the Strange Fates of Ordinary Objects in Nigeria. Seattle: U of Washington P, 2011. [ Links ]

Falcão (ps. Mussagy Narane Talaquichand) personal correspondence with Amy Schwartzott, August 23, 2013. [ Links ]

Finnegan, William. A Complicated War: The Harrowing of Mozambique. Berkeley: UCLA Press, 1992. [ Links ]

Kopytoff, Igor. "The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process." The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Ed. Arjun Appadurai. Cambridge: CUP, 1986: 64-91. [ Links ]

Mabota, Titos, interview with Amy Schwartzott, Maputo, Mozambique, November 11, 2010. [ Links ]

Makolwa (ps. Jorge José Munguambe), personal communication with Amy Schwartzott, September 12, 2013. [ Links ]

Mateus, Dalila. A Luta pela Independência: A Formagäo das Elites Fundadores da FRELIMO, MPLA e PAAIGC. Mem Martins: Editorial Inquéritos, 1999. [ Links ]

Matswa (ps. Ana Vilankulos), interview with Amy Schwartzott, Maputo, Mozambique, May 8, 2011. [ Links ]

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. Introduction to Visual Culture. London: Routledge, 1999. [ Links ]

Noticias. (http://www.canalmoz.com). August 17, 2011; October 24, 2013. [ Links ]

Núcleo de Arte. n.d. [ Links ]

Nwafor, Azinna. "FRELIMO and Socialism in Mozambique." Contemporary Marxism 7 (1983): 28-68. [ Links ]

Opello, Walter. "Pluralism and Elite Conflict in an Independence Movement: FRELIMO in the 1960s." Journal of Southern African Studies 2.1 (1975): 66-82. [ Links ]

Pekiwa (ps. Nelson Augusto Carlos Ferreira), interview with Amy Schwartzott, Matola, Mozambique, August 8, 2008. [ Links ]

Rubin, Arnold. "Accumulation: Power and Display in African Sculpture." Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. Ed. Janet Catherine Berlo and Lee Anne Wilson. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1992 (rptd in abridged form from Artforum 13.9 (1975): 35-47). [ Links ]

Schwartzott, Amy. "Healing the Pain of War through Art-Mozambique's Grassroots Approach to Post-Conflict Resolution: Transformagäo de Armas em Enxadas." Dialogues with Mozambique. Interdisciplinary Reflections, Readings and Approaches on Mozambican Studies. Ed. Björn Bertelsen, Paula Meneses and Sheila Khan. Leiden: Brill, forthcoming 2014. [ Links ]

― . "Transforming Arms into Plowshares: Weapons that Destroy and Heal in Mozambican Urban Art." Representations of Reconciliation: Art and Trauma in Africa. Ed. Lizelle Bisschoff and Stefanie Van de Peer. London: I. B. Tauris Publishers, 2013: 91-109. [ Links ]

Sengulane, Dom Dinis, interview with Amy Schwartzott, Maputo, Mozambique, August 21, 2009. [ Links ]

Sengulane, Dinis Salomáo. Vitória sem Vencidos (Victory without Losers). Maputo: CCM, 1994. [ Links ]

TDM. Catálogo Bienal TDM 9. Maputo: TDM, 2009. [ Links ]

UNECA. Proceedings of Conference on African Conflicts: Management, Resolution & Post-conflict Reconstruction. Addis Ababa: DPMF, 2001. [ Links ]

Zita, Boaventura. A Little Story about the dream of turning weapons into ploughshares (TAE) Project that is becoming a reality. Unpublished ms., n.d. [ Links ]

Zeferino (ps. Zeferino Chicuamba), interview with Amy Schwartzott, Maputo, Mozambique, 2013. [ Links ]