Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Tydskrif vir Letterkunde

On-line version ISSN 2309-9070

Print version ISSN 0041-476X

Tydskr. letterkd. vol.51 n.2 Pretoria Sep. 2014

Constitution Hill: Memory, ideology and utopia

Bill Ashcroft

Australian Professorial Fellow at the University of New South Wales, Australia. His work in postcolonial studies has been instrumental in creating the discipline. Email: b.ashcroft@unsw.edu.au

ABSTRACT

The opening of the Constitutional Court on the 21st March 2004 in Johannesburg was an eventful national day, because, built on the site of the notorious Number 4 prison, the Court symbolized the intention to build a just future out of the memory of oppression. The incorporation of existing prison buildings and materials in the new court building reinforced the discourse of rebuilding and reconciliation that was to characterise the new nation state. As a text the building yields a broader and paradoxical meaning, for the utopian vision of a just future rests in a building in the service of state ideology. This is a paradox because ideology and utopia are regarded as opposites-ideology legitimates the present while utopia critiques it with a vision of a transformed future. However the building demonstrates a feature of ideology that Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch first revealed: that all ideology has a utopian element because without it, no "spiritual surplus, no idea of a better world would be possible." This essay reads the building to show both the function of memory in visions of the future, and the function of utopia in ideology, while using Bloch's theory to interpret the utopian function of the building.

Keywords: Constitution Hill (South Africa), memory, ideology and utopia.

On Human Rights Day, 21 March 2004, the Constitutional Court in Johannesburg was opened by President Thabo Mbeki. The exceptional nature of this event lay in the fact that the Court was built on the site of the most notorious prison in South Africa- Number 4. More importantly, Number 4 was left as a memorial, next to the court, a constant reminder of a past out of which a future nation would be generated. The occasion was particularly symbolic for South Africa's democracy, barely a decade old. In the opening address, Mbeki suggested that the building represents "a shining beacon of hope for the protection of human rights and the advancement of human liberty and dignity" (qtd. in Garson, "Shining Beacon of Hope"). He also spoke of the significance of locating the court on a site associated with an oppressive past, and reinforced the notion that the building is thus intended "to make the categorical statement that our country has broken with its past of despotic and tyrannical misrule, and that henceforth, from here will issue decisions dedicated to the defense and advancement of liberty and human rights" (qtd. in Garson, "Shining Beacon of Hope"). (See figure 1.)

The strategy of incorporating existing prison buildings with the new Court building reinforced the discourse of rebuilding and reconciliation, fundamental tenets of the founding myth of post-apartheid South Africa. In broader terms it coincides with the utopian program of postcolonial African societies generated powerfully, though not solely, through their literatures. But in this case the utopian vision of reconciliation and hope is focused in a building, a building that exists in the service of a state ideology. This is a paradox-ideology legitimates the present while utopia critiques it with a vision of a transformed future. But the union of these two apparently opposed narratives is in fact a demonstration of a feature of ideology that philosophers Ernst Bloch, Karl Mannheim and Paul Ricoeur revealed: that contrary to classic Marxist doctrine, all ideologies have a utopian element, without which they have no power of legitimation. The question is: to what extent can utopia disrupt legitimating power of the ideology that employs it?

A good definition of utopia is offered by Ruth Levitas-the "desire for a better way of living expressed in the description of a different kind of society that makes possible that alternative way of life" (Levitas 257). This concept of an 'alternative' reveals the disruptive potential of utopian thinking that sits uneasily with state ideology, however progressive. In ideology and utopia we find an "interplay of the two fundamental directions of the social imagination" (Ricoeur, "Ideology and Utopia as Cultural Imagination" 27). But the critical feature of the approach to these apparently very different directions by Mannheim, Ricoeur and Bloch is that there is interplay. Contrary to Marxist ideology critique they all find a positive element in the legitimating function of ideology that is borne out of a utopian dimension. The decision to build the court on Constitution Hill, and the architecture of the building itself, are resounding demonstrations of hope for a democratic and constitutionally equitable future. But it is also an ideological building, a state institution. So, how easily does a utopian critique of the present sit with national ideology? This reading of the Constitution Court aims to demonstrate Ernst Bloch's general contention that all ideology has a utopian element; while revealing that the Court itself is a focus of the utopian dimension of South African state ideology.

National ideology and postcolonial utopia

The concept of national ideology is extremely problematic in postcolonial studies. The utopian vision of an independent nation is often dashed after a comprador elite takes over, occupying the boundaries of the colonial state and continuing the trajectory of colonial administration. This has led to a robust questioning of the nation state in postcolonial theory, and much of the utopianism of postcolonial thinkers has extended beyond the state and beyond the nation, because, as Ricoeur points out, "all utopias finally come to grips with the problem of authority" (Ricoeur, Lectures 298). But the advent of the post-colonial nation raises the question of the place of national ideology itself. For all its apparent failures, does the comparatively progressive nature of the national ideology of former colonies require us to see the link between ideology and postcolonial utopia as more nuanced? When state ideology seems to have simply betrayed the pre-independence utopianism of decolonizing countries, does the hope for the future still remain?

The general interpretation of ideology still tends to be pathological: an expression of false consciousness, or the ideas of the ruling class. But if the potentially progressive ideology of the postcolonial nation forces us to think again about ideology, we find that the connection has already been made. Ernst Bloch's 1918 The Spirit of Utopia first raised the idea of the utopian dimension of ideology in the section "The True Ideology of the Kingdom" in which he advocated an alliance of Marxism and religion to produce a 'genuine' cultural, social and historical ideology in "a will to the Kingdom" (qtd. Hudson, 133).1 In this early volume Bloch warned that it was an illusion to imagine that a better society could be based purely on Marxist analyses. Ideology critique as it developed through Althusser, and to some extent the Frankfurt School, "interprets dominant ideology primarily as an instrument of mystification, error, and domination" (Kellner 85). For Marx, ideology is a distortion of 'reality', and Marxist theories of ideology hinge on its identity as false consciousness. Ricoeur makes a canny observation about the consequences of this attitude: "Ideology is always a polemical concept. The ideological is never one's own position; it is always the stance of someone else, always their ideology [...] Utopias are assumed by their authors, whereas ideologies are denied by theirs." (Ricoeur, Lectures 2)

Ricoeur points out that ideology has a significant constitutive function both in legitimation and identification, and that it reflects utopia in certain ways: both can be seen positively and negatively; both have a pathological and constitutive dimension, the pathological always appearing first (Ricoeur, Lectures 1). But crucially, Ricoeur's position might best be explained by the fact that 'reality' itself is framed by ideology (Ricoeur, Lectures 171) and that it is impossible for the critic to escape it. This is generally known as 'Mannheim's paradox'. Mannheim confessed that he was unable to critique ideology from any position outside ideology itself. Ricoeur responded that it was precisely the 'nowhere' of utopia from which ideology could be critiqued (Ricoeur, Lectures 17).

Karl Mannheim's Ideology and Utopia (1936) was the first work to focus directly on the relationship, but it is Mannheim's take on ideology rather than utopia that exercises most critics. Paul Ricoeur's lectures on Ideology and Utopia in 1976 presented one of the most comprehensive discussions of the link between these two apparent opposites (Ricoeur, Lectures). Ernst Bloch's discussion of the utopian dimension of ideology is generally overlooked so it is appropriate to begin with him.

In The Principle of Hope Bloch conforms more readily (than his early Spirit of Utopia) to Marx's dictum that "Ideologies as the ruling ideas of an age, are [...] the ideas of the ruling class" (Bloch, The Principle of Hope 150). But he insisted that ideologies also incorporate the image of a world beyond alienation and that without the utopian function operating even within ideology, no spiritual surplus, no idea of a better world would be possible. Certainly, he concurs, "since ideologies are always originally those of the ruling class, they justify existing social conditions by denying their economic roots and disguising exploitation" (Bloch, The Principle of Hope 149). But in ideology there is an attempt to transcend the present "through its embellishing, condensing, perfecting or signifying exaggeration" (Bloch, The Principle of Hope 149), and for Bloch this is not possible without a distorted or displaced utopian function. Importantly, although distorted, "the original and sustained concrete utopian function must also be discoverable in these inauthentic improvements" (Bloch, The Principle of Hope 149).

Bloch's purpose is at least threefold: on the one hand he is convinced that utopian hope is so fundamental to human life that it characterizes every aspect of social thinking, that the need to grasp the spirit (Geist) of Utopia in human consciousness was fundamental to understanding human life; on another he wants to make a case for progressive socialist ideology, "the ideology of the revolutionary proletariat" (Bloch, The Principle of Hope 155), as something more than mystification. But he also contends that all ideological discourses contain appeals to a better life. They contain a 'surplus' or 'excess' that is not limited to mystification. The point is that while the utopian surplus exists within ideology, it creates tension between the vision and the reality that can expose levels of social inequality while maintaining the hope for justice.

This tension raises the question of the emancipatory potential of a post-colonial state ideology. Bloch's position was not simply that there was 'bad' ideology and 'good' (i.e. socialist) ideology but that all ideology has a utopian element that needed to be understood. Rather than simply denounce ideology Bloch wants to examine ideology for any emancipatory potential. Hence, rather than claim that postcolonial state ideology is progressive (which it is not necessarily) and therefore good, we need to examine ways in which the utopian element of ideology may be maintained as a form of self critique.

Inevitably, for Bloch, the great statements of culture incorporate a spiritual surplus and in Constitution Hill we find a cultural production that Bloch might have called a "great statement."

There is a spirit of utopia in the final predicate of every great statement, in Strasbourg cathedral and in the Divine Comedy, in the expectant music of Beethoven and in the latencies of the Mass in B Minor [...] The exact imagination of the Not-Yet-Conscious thus completes the critical enlightenment itself, by revealing the gold.. .[which] rises when class illusion, class ideology have been destroyed. (Bloch, The Principle of Hope 158)

This may seem to be far too exalted a company for the Constitutional Court, but the point is that the spirit of utopia embodied in architecture rises beyond political motivation, no matter how much the object (a law court) appears to operate in the service of the state. Such "great statements" are ultimately statements of the Not-Yet-Conscious. The way in which the utopian dimension of ideology may retain its critical capacity is its emphasis on the Not-Yet.

On Constitution Hill the physical constitution of memory on which visions of a future-visions that support both the ideology of the state and the hopes of the people-emerges in the architecture of the Court building. The Constitutional Court, which can be regarded as an example of a symbolic discourse, hinges on an interplay of memory, ideology and utopia that objectifies the paradox of the postcolonial state: if utopia is a critique of the present how can it support the promise of legitimacy that underlies state ideology? Or is the emancipatory vision of a newly independent and de-legitimised apartheid state justified in deploying a utopian anticipation of the future in its service? These questions are set in stone, so to speak, in the architecture of the Constitutional Court in which the decorative program of a state building demonstrates a utopianism that may or may not escape the legitimating ideology that produces it. The broader question is: do we need a different form of critique for the interplay of ideology and utopia in postcolonial states, one that transcends the traditional class-based direction of Marxist ideology critique?

The Constitutional Court as a memory of the future

For Karl Mannheim both ideology and utopia are distortions of the 'real' that differ in their mode of distortion, in that ideologies are antiquated modes of belief, products of an earlier, surpassed reality, whilst utopias are in advance of the current reality; "ideologies are therefore transcendent by virtue of their orientation to the past, whilst utopias are transcendent by virtue of their orientation to the future" (Geoghaegan 124). But the orientation to the past, and indeed a defining factor in postcolonial utopianism, is dominated by the ubiquitous and powerful presence of memory, what Idouard Glissant calls a "prophetic vision of the past" (Glissant 64). Here it is memory of a particular kind-that of the violence of apartheid on one hand and of an African cultural heritage on the other. But it is also memory on which the future is built and in this case that memory is concretized in two structures: the preserved buildings of the Number 4 prison and the Constitutional Court itself. So if we read the building as an allegory of the fusion of postcolonial ideology and utopia we see that the "transcendence" of each is not as clearly contrasted as Mannheim's view of ideology. Memory forms the link between ideology and utopia in the postcolonial state and in a curious way memory enables a more open dialogue around the contradictions raised between the utopian vision of justice and the reality of continuing inequality. This is in effect a dialogue between the legitimating function of state ideology and the insurgent function of utopia.

Since the postcolonial 'text' we are reading here is a building it is fitting that memory can be seen to be expressed in several features of its construction: its location, materials, design, community crafters, artworks and the visitors' program put in place on its completion. These are designed to link a vision of the future with social memory, a memory of oppression set within the memory of the deep cultural past. This link, formed in what can be termed symbolic memory, operates in several fields. The concept of symbolic memory is important for what we might call the 'recollection of the future' because it provides a collective foundation on which the future can be realized. Symbolic memory is particularly important in the ideology of the nation-state, and usually represented by monuments and memorials, but the Constitutional Court shows how it may be a basis for a vision of the future.

Location

Constitution Hill is located in the postcolonial city of Johannesburg, and such cities inevitably become sites of a contest between the state and the diversity of the "transnation" (Ashcroft) the exorbitant proliferation of subject positions that flows in, around, and between the structures of the state. As a national edifice the Constitutional Court is designed to resolve this conflict, but the conflict remains as a strong trace of the city's colonial origins. Colonial cities focus the diasporic movement of populations, becoming microcosms of the global flow of peoples that intensifies during and after the period of European imperialism. Similarly Johannesburg, as the economic giant of Africa, drew migrants from all over the continent. Postcolonial cities have always had a fractious relationship with national mythology, which invariably locates itself in the non-urban heartland. This is greatly magnified of course when a white state apparatus controls a black nation. Most colonial cities are established by the colonial administration, freshly minted to further its economic agenda, and in the case of Johannesburg, it arose as a gold boomtown, having no other reason to exist than the discovery of gold in the 1880s.

This character of gold boomtown meant that Johannesburg maintained a diverse, intermixed urban population as its economic centrality drew migrants from all over Africa. The official response to this was panoptic: a prison built in 1892 by Paul Kruger's Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) was extended in 1899 by the addition of ramparts to become a fort. The fort served as a bastion against British incursion during the South African War (1899-1902) but it never played a crucial military role. Its more endemic function was to act as a vantage point from which Kruger's forces could survey the foreign miners (uitlanders) in the mining camp that was Johannesburg below, and who, Kruger believed, were plotting to overthrow him (Gevisser 509).2 When the jails closed in 1983, the site lay abandoned for many years, until in 1996, the judges of the newly established Constitutional Court announced that this was to become the home of the Court.

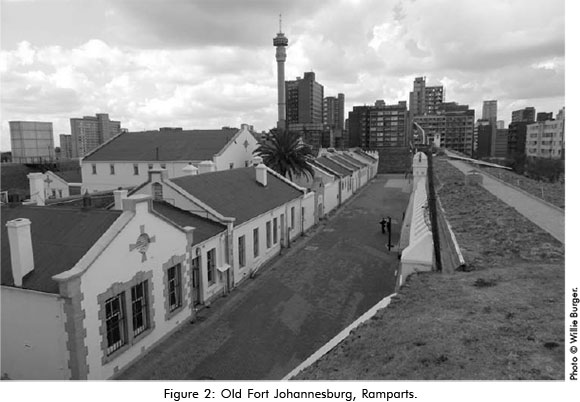

Constitution Hill is a strategic site because its position on a ridge occupies the topographical sign of continuing class and race divisions of Johannesburg society: (see figure 2).

From the ramparts of the Old Fort you look down into the neighborhood and see right into its mass of humanity. Church song rises from the neighbourhood, mingling with the sounds of children playing in the park directly below. The disparities of Johannesburg, and of South Africa more generally, are immediately evident: in one glance you can take in both the inner city with all its social problems and the leafy green forest of Johannesburg's affluent northern suburbs. The ramparts provide perspective over not only space but also time. On one side of the site are the colonial prisons; on the other side is the maximum-security prison of a later era, doors to the cells now ajar, yellow Highveld grass rising in the cracks of the courtyard. (Nuttall 507-08)

So it was on this hill, on this grim reminder of apartheid history, a reminder of the continuing divisions in South African society that the Constitutional Court was built. Given the panoptic origins of the site and the historic diversity of the population, its function as a unifying symbol becomes extremely important. "The literal space of the building assumes for the moment the imagined place of nationhood, as it grants the visitor the thrill of what it might mean to 'belong'. The question of 'belonging', both to the city and the nation, lies at the heart of the new court project." (Freschi 33)

Because Johannesburg came to postcolonial status in what may be regarded as a post-national world the question of belonging assumes a particular complexity. The post-independence euphoria of African countries in the 1960s, euphoria soon replaced by disillusionment, has not been quite the same experience of post-apartheid South Africa, perhaps because, coming much later, the expectations of the population have been more cautious (or more cynical), and ironically, its civic institutions more stable. Consequently the ANC government appears to have avoided the route taken by other decolonized nations of erecting signature public buildings as symbols of the state. The Constitutional Court represents a radical way of rethinking the role of public buildings in imagining a South African identity grounded on notions of unity in diversity. If, as many believe, the ideology of South Africa as a postcolonial nation has focused less on nationalism and independence and more on identity, culture and community, (a profoundly utopian notion itself) then this is reflected in the both the discourse surrounding Constitution Hill and the decorative program of the Court's architecture.

The location of the building, between the former 'Native' prison, Number 4 and the Fort where white prisoners were kept, demonstrates how a vision of the future situates itself in cultural memory. This metaphorical bridge between black and white, rich and poor, past and future can be seen in the location of Constitution Hill itself between the poor black suburb of Hillbrow and the Civic Centre to the West, while the affluent white suburbs can be seen to the north. For Freschi this can be read in positive terms so that the location "mediates the binaries of poverty and affluence, of urban decay and suburban development, by creating a focal point for an imagined community, which embraces these differences as a necessary and ineluctable part of its definition of self" (Freschi 37). So, in one sense the location faces the reality of a harsh memory as it looks to the future. However, the imbalance highlights the tension between the utopian promise of unity and justice and the ideology of nation building encapsulated in the Court. Nationalist rhetoric habitually suppresses the reality of social inequality in the interests of the imagined unity on which the nation is built, and this is the tension on which the Court building is specifically located. It is a tension about which some critics are far from euphoric: "As Constitution Hill continues to assert the great merits of the new constitution in the face of increasing urban poverty, loss of jobs, lack of housing, and neo-liberal resource privatisation, the law's inability to deliver on the promise of a new social, political, and economic order is made clear." (Douglas 172)

While the function of utopia is to critique the present with a vision of the future the ideological requirements of the state render the dialogue between ideology and utopia peculiarly ambivalent. But this is why memory is so important to form a bridge between past and future, between reality and possibility, because while the future signifies the Not-Yet, memory offers at least the possibility of refusing to gloss over the inequalities that carry over from past to present.

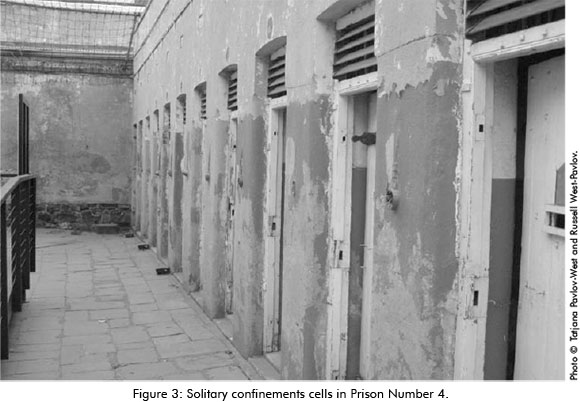

Visiting Number 4: How memory materializes

The first signifiers of a non-discursive memory are the materials used to build (or decorate) the court and the material function of memory begins in the gaol, where the materialization of memory can be found in the physical presence of the cells and exercise yards of Number 4 (see figure 3). The gaol was called that "because the black male section was 'section four,' and those two words still send shivers down people's spines" (Gevisser 508). Although not everybody had been locked up here, everybody in Johannesburg has lived with Number 4 on their minds. After all, anything could constitute a pass violation. Nolundi Notamo, a pass offender recalls: "My grandmother had taught us to say goodbye when we went to shop in town, because we never knew if we would come back or not. We used to say, 'If you don't see me, check for me at Number Four'" (Madikida et al. 18). Moving through the prison there are stories and small museums dedicated to those like Mahatma Gandhi who refused to pay a fine in order to show solidarity with the victims of the regime. Although not a political prison, the line between political prisoners and criminals was difficult to draw given the nature of the justice system under apartheid. But many of the major resistance figures against apartheid-Nelson and Winnie Mandela, Fatima Meer-spent time in Number 4.

The stories tell a grim history. But memory is contained in something more than the official history, something more than the stories of inmates, even something more than the blankets rolled to make couches for the cell boss, or replicas of tanks or trucks for a prison competition. It is memory any visitor can sense-a memory in the very bricks and stones themselves. This memory dwells there beyond narrative, beyond interpretation, even beyond the graffiti that inscribes the prisoners' existence on its walls. Memory in Number 4 is a presence that offers a kind of 'knowing' beyond the narrative of history. The visitor feels that if the historical narrative were suppressed the memory would remain in the ugly reality of the cells. "You really do feel when you walk into it that you're entering the dark heart of apartheid, that you're treading on bones" (Gevisser 513).

This, perhaps, is the way memory materializes, the way the experience of memory may be shared. But with the stories of the treatment of prisoners comes bafflement. Why so much humiliation? Unfair and unjustified incarceration is one thing. But why the gratuitous humiliation of the tauza dance, which prisoners were forced to perform to show that they were not hiding anything in their anuses? Why the sadistic humiliation of meal times where prisoners sat in lines on a sloping exercise yard that looked up into exposed toilets? Why allow the showers to be controlled by the prison's dominant gangs? Clearly the answer lies in apartheid itself. It exists not simply for control but for humiliation, for de-humanizing, and ultimately it de-humanizes both perpetrator and victim, both white and black. Something of this remains in the cells- so manifestly were the buildings of Number 4 constructed for their carceral function, so resolutely do they hold the memory of apartheid that they resist re-use for any other purpose.

Such a past offers a ready trap for resentment, but it can also be the basis for a vision of the future. In the words of African-American formulator of pan-Africanism, Alexander Crummel, "What I would fain have you guard against is not the memory of slavery, but the constant recollection of it, as the commanding thought of a new people, who should be marching on to the broadest freedom in a new and glorious present, and a still more magnificent future." (Crummel 13) There is a great difference between the constant recollection of apartheid and the memory of it, and this difference is captured by the phenomenon of symbolic memory, seen in a Johannesburg building in which memory reaches beyond apartheid.

Importantly, the symbolic memory of apartheid in the Number 4 prison is connected to another symbolic memory, that of South Africa's secular saint, Nelson Mandela, who spent time in Number 4 and who died at 95 on December 5, 2013. The memory of Mandela is symbolic because, like the memory of an 'African' past, his life has been asked to represent much more than one life could contain. But most importantly, for white and black he represented hope for South Africa. This feeling of a possible future is expressed by a white journalist, Larry Schlesinger, who remembers the day of the democratic elections in 1994: "There was something in the air that day. Yes the tension remained, but there was the sense the dream could be real, that we could all learn to get along and in doing so rebuild and repair centuries of inequality, injustice and brutality. It would not be easy, but it was possible." (Schlesinger)

Whether Constitution Hill builds a monument to the past or establishes a memorial looking to the future may depend on how the memory of Mandela comes to be positioned in the ideology of the state. There is much about Mandela that was conveniently forgotten: he criticized the Iraq war and American imperialism; he called freedom from poverty a "fundamental human right"; he criticized the "War on Terror" and the labeling of individuals as terrorists, even Osama bin Laden, without due process; he criticized racism in the US; he refused to abandon Castro or Gaddafi who supported the ANC's war against apartheid; he supported labour unions passionately (Shen and Legum). His deification to an international saint has been at the expense of suppressing much of his international activism but he remains important to the memory of apartheid because he embodies the fact that change is possible.

Ultimately, some part of the hope that Mandela symbolizes is captured in the structure of the Constitutional Court.

The 'Decorative Program'

Investing the utopian potential of South African society in a building raises a peculiar problem: if the anticipation embedded in the utopian potential of the Court is assumed to have already been achieved just by erecting the building, then the building becomes irredeemably ideological by legitimating the state that supports it. For instance posters celebrating the twenty-seven human rights enshrined in the Constitution are a moving evidence of the utopian intention of the court, but they have a sense of completion that problematizes that intention. The very solidity of the building militates against the critical dimension of utopian anticipation. However the interesting thing about the Constitutional Court is that although it was voted South Africa's best building in 2006, it is the decorative elements that provide its utopian statement. Federico Freschi makes the point that the building's task of imagining a democratic South Africa is "conveyed entirely through its decorative program":

In this way, its decorative program, rather than its architecture per se, suggests a shift in the discourse of public architecture away from staid notions of civic decorum and conventionalized grandeur, toward open-endedness, inclusivity, and a sense of a deliberate playing with the elements and expectations of the public space in relation to notions of individualized and personal place. (Freschi 30)

This decorative program involves several features, including the use of materials, interior design, community-workshop crafters and commissioned artwork, all of which are driven by the need "to establish a visual rhetoric of 'community united in diversity'" (Freschi 30). The decorative program suggests an observation of Bloch's on the importance of cultural production to utopia. For him "Utopian function tears the concerns of human culture away from [...] an idle bed of mere contemplation" (Bloch, The Principle of Hope 158). What may appear 'mere' decoration, becomes, when it extends beyond the period of the dominant ideology, an embodiment of hope. But such hope is invested, as it is in all postcolonial utopianism, in memory.

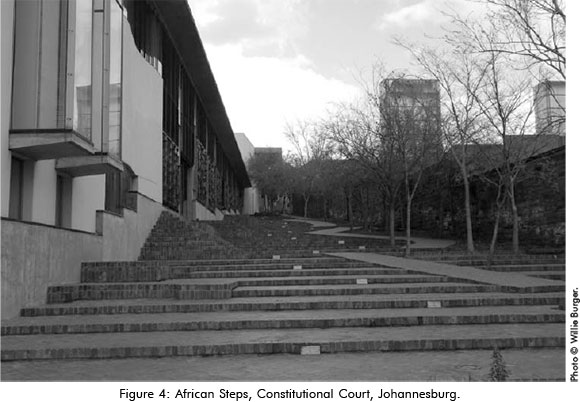

To invoke this memory the materials used in the building are particularly significant. Just as the memory of apartheid materializes in the stones and bricks of Number 4 so the materials used in the court are directly symbolic of social and cultural memory. For example the most symbolic element of the court are the Great African Steps, a walkway built with red bricks salvaged from the Awaiting-Trial Prison, which was demolished to make way for the court, and which divides the court from the old Women's Gaol (see figure 4).

While the African steps appear to soften the nationalist ideology with the metaphoric representation of a broader African past, such a past legitimates the state and generates the state's need for ". buildings that reinforce a belief that people's ties to a heroic past or a promising future are their important identities: that the immediate effects of their actions are trivial compared to their historic mission." (Edelman 83)

Freschi responds that

This belief is most obviously expressed in Constitutional Court by the Great African Steps, which, in effect, are not particularly great, either in scale, or in their denial of wheelchair access. Essentially an invention of a (re)-imagined past, these steps are a clear and, seen against the potency of the site and its associations, completely unnecessary example of an "official nationalist" imagining of identity and authenticity (Freschi 44).

Whether the "African Steps" are "unnecessary" as Freschi claims, they augment the very necessary ideological function of declaring the ancient heritage of the new nation. All nations invent an ancient past, but the fact that these are steps which extend up the hill between the adjacent Number 4 Gaol and Constitutional Court complex- leading up from the level of the solitary confinement cells to the court entrance- symbolizes a process by which the future is both connected to and shaped by the past. The ambivalence of this employment of an archaic African heritage is the ambivalence of the utopian dimension of ideology, but the concept of process in the structure keeps the future trajectory of memory firmly in view. In effect, the future is remembered, not by the recollection of apartheid, but by the memory of an African heritage- Glissant's "prophetic vision of the past" (Glissant 64).

The references to the African past, rather than anything specific to the city are also implied in a stylized tree, which, conflated with the South African flag, informs the design of the court's logo and which serves as a structural metaphor in the foyer. The notion of a tree as a metaphor of place and community reflects a somewhat generalized interpretation of the Southern African tradition of dispensing justice from beneath a tree-what the Constitutional Court of South Africa website recalls as "the trees under which African villagers traditionally resolved their legal disputes" (Freschi 42). However, the metaphor has been somewhat adapted to the purpose of the court, because traditionally only the adult men of a community were invited to participate (Freschi 42).

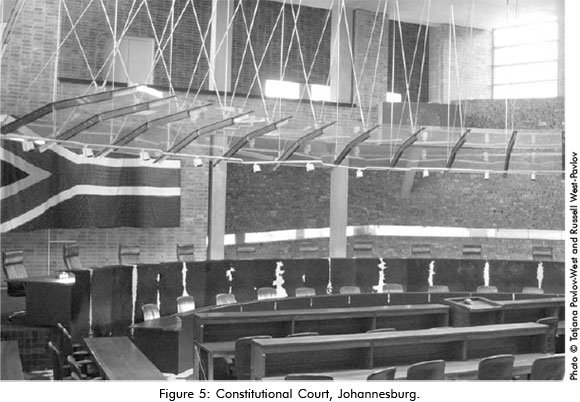

To symbolize the function of memory in the building the same bricks have been dry-packed in the main courtroom behind the judges' dais "placed in rough lines, looking almost unplastered, a rich striking red wall," while "the north wall is almost all glass, flooding the room with light" (Garson, "The Constitutional Court Opens for Business"). (See figure 5.)

The brick wall is a material sign of the place of memory in the rebuilding of the future. It serves to remind the visitor that the court is "a place where you find yourself between the past and the future, and where you understand that the only way the future can happen, resting on the past, is through your agency as someone in the present" (Gevisser 511). Just like the stones and architectural features of Number 4, the bricks are an open signifier, easily captured by the state ideology of bridging the past and future, but not limited to it. Their roughness alone is a sign of a memory that cannot be fully articulated. Thus the brick wall, like Number 4 offers the presence of a memory that cannot be entirely captured by language.

The importance of memory in building an imaginative, locally inflected symbolic space is also demonstrated by the policy of engaging community-workshop crafters so that in the words of the official prospectus, "This idea of many hands having created the court is an extension of the principles that resulted in the writing of our new democratic constitution [...] The Constitutional Court building is accessible to all, it is the icon of our democratic struggle." (Government of South Africa; qtd. in Freschi 41)

As well as inclusivity, the use of traditional crafters involves the cultural memory of craft skills directly in the building. The use of community crafters provided a model of communal involvement that was continued in the visitor program based on the lekgotla or traditional dialogue that includes public debates, lectures and seminar series (Madikida et al. 18), some of which make an attempt to include the participation of former prisoners whose memories form part of the discourse of transformation that the building symbolizes. The process of transformation is often enacted in the act of memory itself:

Using drawing, painting, or sculpture to explore memory gave both connection and distance, connection because these were memories closely known and distance because the act of learning a new language diverted attention away from what was being said to how it was said. Making something physical in this way functioned both as defense and means of exposition. The unfamiliarity of the medium acted as a kind of buffer between the traumatic experience and its confrontation. (Madikida et al. 22)

The visitor program continues a number of symbolic features incorporated into the building by emphasizing such processes as ways in which the future can be achieved.

Museums and symbolic memory

The function of memory in Constitution Hill may be viewed in the context of other museums and memorials, such as the District Six museum in Cape Town, Freedom Park in Pretoria and the Hector Pieterson Museum in Soweto, which work either tangentially or in opposition to the Court building. The Hector Pieterson Museum, exhibits photographs of and around the march on 16 June 1976 by students protesting at being forced to be taught through the medium of Afrikaans, a language they associated with oppression. The Pieterson museum is a testament to the power of visual memory. Dedicated to Hector Pieterson, who was one of the first killed by police, it arguably owes its existence to the fact that photographer Samuel Nzima, happened to be standing by as Hector was deliberately shot down. The photo of his anguished sister, Antoinette Sithole, and 18-year old schoolboy, Mbuyisa Makhubu, carrying the dead boy in his arms flashed around the world. Some images seem to encapsulate an entire conflict, even an entire state philosophy. The photographs, which give immediacy and power to the memory of what is in effect a single day, appear to function as an active memory but they have a powerful symbolic function vested in the youth of the victims, the brutality of the police and the cause of the protest-the Afrikaans language.

Freedom Park, which is located within view of the Afrikaner Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria has a mandate that echoes the function of memory in Constitution Hill, a memory that leaps over the period of apartheid to locate the present in an ancient planetary history. Its location, in view of the Voortrekker monument is particularly strategic, offering the view of a museum to the static monumentalism of the Voortrekkers. The mandate of Freedom Park, according to the official website is

... the creation of a memorial and monument that will narrate a story spanning a period of 3.6 billion years through the following seven epochs: Earth, Ancestors, Peopling, Resistance and Colonisation, Industrialisation and Urbanisation, Nationalism and Struggle, Nation Building and Continent Building; as well as the Garden of Remembrance to acknowledge those that contributed to the freedom of the country. (Freedom Park)

Here again the future is embedded in the symbolic memory of an ancient African past now measured in billions of years. The extent of this time span seems to promise a future that encompasses far more than nostalgia, far more than a recovery from the trauma of apartheid. It is a memory in which the Voortrekker Monument appears to stand for one fleeting episode.

The District Six Museum in Cape Town is a memorial based on the time in 1965 when the South African apartheid government forcibly removed its occupants and declaring the area a "whites-only" zone. 60 000 people were removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as the Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. As these residents moved away to the suburbs, the area became the neglected ward of Cape Town and today a historical Cape Town attraction. Like the Hector Pieterson Museum this museum has a particular historical focus, but has, arguably, a very different relationship to ideology than Constitution Hill. According to Douglas,

... the District Six Museum offers a provocative interplay of challenges to fixity that forward more open and fluid imaginations of subjectivity that question the centrality of the law and the nation as the organising force of political community. Moreover, the learning programs at the District Six Museum offer an explicit critique of the promise of law within a liberal-democratic capitalist order through an exploration of anti-capitalist post-apartheid subjectivities. (Douglas 172)

Questioning the centrality of the law suggests a utopianism that actively resists the ideology of the state.

The various forms of memorial hint at different ways in which utopia and ideology interact. But the crucial question running through them all is: to what extent is the promise of a utopian future generated and maintained by the false consciousness of state ideology? All economic systems have a ruling class and the ANC's answer to the fact that the ruling class in South Africa was white was to create a black elite. It is arguable that the utopian element of ideology is merely a mask to the maintenance of the power of the ruling elite. A specific example of this ambivalence is the Ladder of Freedom in the Constitutional Court, whose bottom rungs are wrapped in barbed wire, which gives way to a rung of ivory (as elephants never forget) and end with a snake to symbolize wisdom. Although the barbed wire signifies the struggle necessary to begin the climb the ladder does not lean against a wall or point to the constitution, and in the words of one critic:

Though the future may not be entirely clear, it is evident from the ladder that the future will continue to deliver the gifts of evolutionary progress such as wisdom and justice and, further, that there is indeed a teleologic line between the past and the future [...] The naturalisation of both evolutionary time and its culmination in statebased liberal-democracy accords a significant amount of power to these forces. (Douglas 179)

For Douglas the utopian promise of justice and equality is little more than a sham, and this reflects the widely held idea that ideology is primarily an instrument of mystification, error, and domination. Yet having the ladder of freedom ending 'nowhere' is precisely the way in which utopia escapes ideological distortion, for this nowhere is the only place from which ideology can be critiqued:

Is not utopia-this leap outside-the way in which we radically rethink what is family, what is consumption, what is authority, what is religion, and so on? Does not the fantasy of an alternative society and its exteriorization 'nowhere' work as one of the most formidable contestations of what is? (Ricoeur, Lectures 16)

Ricoeur suggests that utopia becomes important because the use of power exposes a credibility gap in all systems of legitimation, all authority. Utopia exposes the credibility gap wherein all systems of authority exceed both our confidence in them and our belief in their legitimacy. Central to his theory is the function of power and how the problem of power is subverted by utopia.

This, we might say, exposes the fatal flaw of 'achieved' utopias, because no utopia can fully resolve the problem of power. Indeed it is this problem that has seen the collapse of political and social utopias into dystopias. But Ricoeur suggests that

All the regressive trends so often denounced in utopian thinkers-nostalgia for the past, for some paradise lost-proceed from this initial deviation of the nowhere from the here and now. Ultimately the nowhere is the source of both the paradoxes of utopia and the exposure of the pathology of ideological thinking, which has its blindness and narrowness precisely in its inability to conceive of a nowhere. (Ricoeur, Lectures 17)

The Ladder of Freedom is not teleological precisely because it ends nowhere, the only place from which the ideology of the state can be critiqued.

Ricoeur turns to Clifford Geertz's view of ideology as symbolic action as the only one that attempts to understand how ideologies actually work. If we understand all action as symbolically mediated we open up the possibility of comparing an ideology with the rhetorical devices of discourse. This is not unlike Bloch's theory that ideology works not only in political rhetoric but also in the phenomena of everyday life. The concept of ideology as symbolic action, or discourse helps us understand that the imagination, apparently co-opted by the state in the Constitutional Court, can work in two ways, to preserve or disrupt order:

On the one hand, imagination may function to preserve an order. In this case the function of the imagination is to stage a process of identification that mirrors the order. Imagination has the appearance here of a picture. On the other hand, though, imagination may have a disruptive function; it may work as a breakthrough. Its image in this case is productive, an imagining of something else, the elsewhere. In each of its three roles [integration, distortion, legitimation], ideology represents the first kind of imagination; it has a function of preservation, of conservation. Utopia, in contrast, represents the second kind of imagination; it is always the glance from nowhere. (Ricoeur, Lectures 265-66)

The conclusion to be drawn from this is that the Constitutional Court stimulates two kinds of imagination. While ideology appears to co-opt utopia to its program of integration, distortion and legitimation, it also works to open up the future because utopia is the nowhere from which the state, with its narrative of struggle and triumph, can be critiqued. It is the space that ideology can never control. What is at stake here is power and it is here that ideology and utopia intersect. For if ideology is the surplus value added to the lack of belief in authority, as Ricoeur contends, utopia is what unmasks this surplus value (Ricoeur, Lectures 298). Despite the operation of utopia within ideology all utopias finally come to grips with the problem of authority.

In the end there is no special dispensation for postcolonial state ideology, socialist or otherwise, nor do ideology and utopia resolve themselves into a simple binary of good and bad. Rather the utopian element, what Bloch calls the Not-Yet, is present within the ideological structure of the Constitutional Court in a way that disrupts the legitimating function of ideology. This is because, as both art and architecture the Court building carries a spiritual surplus that escapes the confines of state ideology and it is within this surplus that the utopian intention to change the future, the belief in a better world, operates in the free space at the end of the Ladder of Freedom-the space of nowhere.

Works Cited

Ashcroft, Bill. "Transnation", in Re-routing the Postcolonial: New Directions for the New Millenium. Eds. Janet Wilson, Cristina Sandru and Sarah Lawson Welsh. London: Routledge, 2010. 72-85. [ Links ]

Bloch, Ernst. The Spirit of Utopia. Trans. Anthony A. Nassar. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2000. [ Links ]

―. The Principle of Hope. Trans. Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice and Paul Knight. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1986. 3 vols. [ Links ]

Crummel, Alexander. Africa and America: Addresses and Discourses. Miami: Mnemsonyne, 1969. [ Links ]

Delmont, Elizabeth. "Re-Envisioning South African Heritage Development in the First Decade of Democracy". African Arts (Winter 2004): 30-35. [ Links ]

Douglas, Stacy. "Between Constitutional Mo(nu)ments: Memorialising Past, Present and Future at the District Six Museum and Constitution Hill". Law Critique 22 (2011): 171-87. [ Links ]

Edelman, Murray. From Art to Politics: How Artistic Creations Shape Political Conceptions. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1995. [ Links ]

Freedom Park. n.d. Dec. 2013. <http://www.freedompark.co.za> [ Links ].

Freschi, Federico. "Postapartheid Publics and the Politics of Ornament: Nationalism, Identity, and the Rhetoric of Community in the Decorative Program of the New Constitutional Court, Johannesburg". Africa Today 54.2 (Winter 2007): 27-49. [ Links ]

Garson, Philippa. "Constitutional Court: A "Shining Beacon of Hope"". 23 Mar 2004. Nov 2013. <http://www.joburg.org.za/index.php?option=com_ content&view=article&id=1195:constitutional-court-a-sMning-beacon-of-hope&catid=122:heritage&Itemid=203> [ Links ].

― . "Constitutional Court: an Artwork Through and Through". 19 Febr 2004. Nov 2013. <http://www.joburg.org.za/index.php?option=com_ content&view=article&id=1187:constitutional-court-an-artwork-through-and-through&catid=122:heritage&Itemid=203> [ Links ]

―. "The Constitutional Court Opens for Business". 04 Febr 2004. Nov 2013. <http://www.joburg.org.za/index.php?option=com_ content&view=article&id=1189:constitutional-court-opens-for-business&catid=122:heritage&Itemid=203> [ Links ]

Geoghegan, Vincent. "Ideology and utopia". Journal of Political Ideologies 9.2 (2004): 123-38. [ Links ]

Gevisser, Mark. "From the Ruins: The Constitution Hill Project". Johannesburg: The Elusive Metropolis. Eds. Achille Mbembe and Sarah Nuttall. Spec. issue of Public Culture, Society for Transnational Cultural Studies 16.3 (2004): 507-20. [ Links ]

Glissant, Idouard. Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays. Trans. with introd. J. Michael Dash. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1989. [ Links ]

Government of South Africa. "The New Constitutional Court Building Selected Artwork Competition Briefing Document" section 1. Johannesburg: n.d. [ Links ]

Hudson, Wayne. "Ernst Bloch: Ideology and Postmodern Social Philosophy". Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory/ Revue Canadienne De Thiorie politique et sociale 7.1-2 (Winter 1983): 131- 45. [ Links ]

Kellner, Douglas. "Ernst Bloch, Utopia and Ideology Critique". Existential Utopia: New Perspectives on Utopian Thought. Eds. Patrica Vieira and Michael Marder. London: Continuum, 2011. 83-96. [ Links ]

Kentridge, William. "Rand Mines". William Kentridge Prints. Ed. David Krut et al. Johannesburg: David Krut Publishing, 2006. [ Links ]

Kinna, Ruth. "Politics, Ideology and Utopia: a Defence of Eutopian Worlds". Journal of Political Ideologies 16.3 (2011): 279-94. [ Links ]

Law-Vljoen, Bronwyn. Light on a Hill: Building the Constitutional Court of South Africa. Johannesburg: David Krut Publishing, 2006. [ Links ]

Levitas, Ruth. "The Future of Thinking about the Future". Mapping the Futures: Local Cultures, Global Change. Eds. J. Bird, B. Curtis, T. Putnam, G. Robertson and L. Tickner. London/New York: Routledge, 1995. 257-66. [ Links ]

Madikida, Churchill, Lauren Segal and Clive Van Den Berg. "The Reconstruction of Memory at Constitution Hill". The Public Historian 30.1 (February 2008): 17-25. [ Links ]

Mannheim, Karl. Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge. London and New York: Routledge, 1936. [ Links ]

Nuttall, Sarah. "Introduction". Johannesburg: The Elusive Metropolis. Eds. Achille Mbembe and Sarah Nuttall. Spec. issue of Public Culture, Society for Transnational Cultural Studies 16.3 (2004): 507-20. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, Paul. "Ideology and Utopia as Cultural Imagination." The Philosophic Exchange 2.2 (1976): 17-28. [ Links ]

― . Lectures on Ideology and Utopia. Ed. George H. Taylor, New York: Columbia UP, 1986. [ Links ]

Schlesinger, Larry. "What Nelson Mandela gave me: Hope for the Future of South Africa", Crikey Daily Mail. Dec 6 2013. n.d. <http://media.crikey.com.au/dm/newsletter/dailymail_ 567288fbf03ded65634fd5dbf9019273.html#article_27773> [ Links ].

Shen, Aviva and Judd Legum. "Six Things Nelson Mandela Believed that Most People Won't Talk About", Think Progress. 6 Dec 2013. n.d. <http://thinkprogress.org/home/2013/12/06/3030781/nelson-mandela-believed-people-wont-talk/> [ Links ].

Van der Merwe, Clinton D. "Environmental Justice-A New Theoretical Construct for Urban Renewal? The Case of Heritage at Constitution Hill, Johannesburg", Environmental Justice 2.1 (2009): 25-34. [ Links ]

1. In private correspondence Bloch was scathing about Mannheim's unaccredited deployment of Bloch's views on the link between Ideology and Utopia.

2. Its most striking and perhaps symbolic features are the ramparts camouflaged as a hill, while the facade, with its ZAR coat of arms, was built on the inside. As Mark Gevisser notes this is a compelling image of the Dutch colonists' laager mentality, and in retrospect a metaphor of the inwardness and shortsightedness of their heirs, the Afrikaner nationalists. (Gevisser 510).