Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Surgery

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5151

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2361

S. Afr. j. surg. vol.60 no.1 Cape Town mar. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2078-5151/2022/v60n1a3571

ONCOLOGY

The influence of HIV status on the duration of chemoradiotherapy for anal squamous cell carcinoma

AR ZubiI, II; DJ SurridgeI

ISchool of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

IIFaculty of Medicine, Benghazi University, Libya

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The HIV epidemic has changed the demographic of patients with anal squamous cell carcinoma. The influence of HIV status on the ability to complete standard chemoradiotherapy was studied

METHODS: A retrospective analytic observational study was conducted of all patients presenting to the Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital radiation oncology department with anal squamous cell carcinoma from January 2014 to December 2016. Standard chemoradiotherapy was offered to all patients. Stage of anal squamous cell carcinoma, HIV status and cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) levels were measured and compared in groups. We considered a maximum of 42 days as complete therapy without delay

RESULTS: Ninety-two patients with anal squamous cell carcinoma were identified, of whom 67 were seen with the intention to treat and had known HIV status, of whom 59 received chemoradiotherapy. Eighty-eight per cent were people living with HIV (PLWH). PLWH were younger (p < 0.001) and less likely to receive full-dose chemotherapy (63%, p = 0.41). No patients presented in stage 1. More than 60% presented in stage 3. Fifty-six per cent of PLWH and 57% of HIVnegative patients were able to complete the 50 Gy radiation in 42 days (p = 1.0). CD4 above 200 did not impact therapy (p = 0.71

CONCLUSION: HIV status of anal squamous cell carcinoma has minimal impact on the duration of chemoradiotherapy

Keywords: HIV, chemoradiotherapy, duration of treatment, anal cancer, squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

An increase in the incidence of anal squamous cell carcinoma (ASCC) has been reported in recent years.1 The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic has altered the demographics and clinical progression of this disease, changing it from one that mainly involved women over the age of 58 to a disease of young people.2,3 The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has improved the survival rate and the immune function of people living with HIV (PLWH). There has also been an increase of nonAIDS defining cancers, including ASCC among PLWH.3

There is conflicting evidence regarding PLWH receiving HAART. Some studies have revealed poor tolerance and response to chemoradiotherapy (CRT),4-7 while others have shown no difference in acute toxicity between immuno-competent and immunodeficient patients.8-11 All these data were obtained from small, retrospective studies. More recent trials have shown no effect of immune status on toxicity or efficacy of CRT.10,12 Recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that patients with ASCC be treated similarly, regardless of their HIV status.13

CRT is associated with major toxicities in up to 80% of patients, necessitating treatment breaks.13 The longer the treatment breaks, the poorer the outcomes.14 It has been shown that not only the duration of the treatment break, but also the total treatment time of CRT impact survival.11,15,16

A sub-analysis of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 92-08 study showed that PLWH who were treated without breaks responded to chemoradiation similarly to HIV-negative patients. They are usually on HAART and have a healthy immune system.3

This study aimed to determine if HIV affected the duration of CRT for ASCC.

Methods

We performed a retrospective observational study of patients diagnosed with ASCC who presented to the radiation oncology department at the Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH) during the period 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2016. Only patients 18 years and older, with known HIV status and who had received CRT were included. The diagnosis had been confirmed with a histologic report.

HIV status, cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) count and viral load (VL) were recorded within three months of biopsy date and before starting CRT. Patients were staged according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification.

The patients had received 50 Gy radiation as standard therapy, delivered by a Multileaf collimator machine, using 3D conformal technique. This was administered as 30 Gy large field, followed by 20 Gy reduced field in 2 Gy fractions. Treatment finalised within 42 days was considered 'complete'. Patients then reassessed for 10 Gy boost. We took the 50 Gy as our endpoint.

5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 400 mg/m2 (as a bolus dose) was administered with fractions 1-4 and 22-25 of radiotherapy, and mitomycin C 10 mg/m2 or cisplatin 70 mg/m2 was administered with fraction 1 and sometimes fraction 22 of radiation, depending on the clinician's preference (mitomycin C was no longer available after July 2015). Chemotherapy was not prescribed for patients with a CD4 count < 200. During the period of this study, VL was not considered routinely.

Statistics

We used the website www.socscistatistics.com for statistical calculations. Fisher's exact test or Pearson's chi-square test was conducted to test the significance of association between categorical variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for normality; for the numerical data the Mann-Whitney test or t-test was performed. A 2-sided a level of 0.05 was selected.

Results

One hundred and two qualifying patients were identified. Forty-three cases were excluded for incorrect diagnosis, therapy received elsewhere or had not started CRT (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in parameters shown in Table I between PLWH and HIV-negative patients except that PLWH were younger (mean 41 years vs 61 years, p < 0.001).

CRT

Eighty-eight per cent of PLWH and 71% of HIV-negative patients received 50 Gy radiotherapy, over a mean duration of 41 and 37.6 days, respectively (p = 0.23). However, only 56% and 57% of PLWH and HIV-negative patients, respectively, were able to complete the dose within 42 days. This was not statistically significant (p = 1) (Table II).

None of the parameters seen in Table II influenced the duration of CRT. CD4 counts were available for 40 PLWH (77%) and VL for 29 PLWH (56%) was available. No significant difference was seen between PLWH who completed the CRT and those who did not (Table II).

Toxicity

Two patients passed away after CRT was initiated. Both on-treatment deaths were in PLWH: one died from severe cutaneous reaction (burns), and the other from severe haemorrhage at the stoma site secondary to pancytopenia.

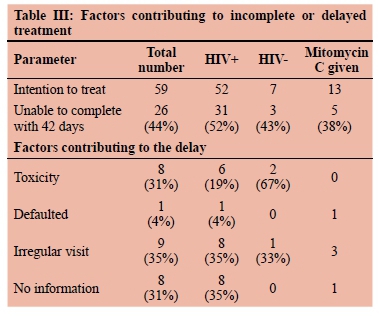

Almost all the patients (55/56, 98%) developed some toxicity. However, in only eight cases (31%) was the toxicity severe enough to interrupt the standard dose of RT, which was either not completed (four cases including the two deaths) or was administered over an extended period (four cases, median duration 49 days). Ten patients (39%) did not complete the CRT for non-medical reasons; eight of them were PLWH. One of those ten patients defaulted, the other nine patients did not attend the treatment regularly (Table III).

Thirteen patients (22%) received mitomycin C. Only 38% of those were unable to complete the CRT within 42 days, mainly due to irregular visits that were not related to toxicity (Table III).

Discussion

In line with findings in the literature, PLWH who presented with ASCC were significantly younger than HIV-negative patients.4-8,17 Previous studies found that PLWH with ASCC were most often men,4-11,17,18 however, in this study, women were predominant among both PLWH and HIV-negative patients. This might be explained by the fact that more PLWH in South Africa are female.19

Most of the patients presented with advanced disease, as has been reported in previous studies from South Africa.20,21Node involvement was present in 63% of our cohort, in comparison with less than 50% reported in studies undertaken in Europe and USA.9,14,1617,22,23 For example, only 32% of 740 patients and 26% of 644 patients who participated in ACT II22 and RTOG 98-1123 trials were node-positive. This may be attributed to poor health-referral systems and misdiagnosis at primary healthcare level. Low education levels, poverty and problems accessing healthcare facilities could also contribute to the delay in seeking medical care.24

A far higher ratio of patients with ASCC were PLWH (88%) compared to findings in any published paper that were consulted,4-6,8,9,17,25 but the percentage is similar to a study from KwaZulu-Natal in which PLWH constituted 77% of ASCC patients.20 This may be attributed to the endemic nature of HIV in South Africa.19 Surprisingly, in a study from Cape Town (conducted from 2000 to 2004), only one out of 31 patients tested positive for HIV.21

In the current study, just over a half of the 59 subjects with the intention to treat were able to complete the CRT within 42 days (median 36 days, range 32-42). Toxicity was not the only factor that influenced the failure to complete CRT. Nine patients (31%) failed to visit the hospital regularly for treatment and a patient defaulted before completing CRT (Table III). These poor results could be attributed to the following factors: first, most of the patients presented with advanced disease. Second, poor socio-economic status and a lack of accessibility to the treatment facility appeared to be significant factors. It is important to mention that almost a third of the patients who did not complete the RT had no information in their file to indicate the cause of the delay (Table III). It is worth mentioning that, of the eight patients excluded because they had not initiated CRT, five defaulted and three died. All eight were PLWH. This may indicate that PLWH were more prone to default.

Although mitomycin C is more toxic than cisplatin,23 none of the 13 patients who received mitomycin C developed severe toxicity, which could have delayed or interrupted the administration of the standard dose. Five patients (38%) of those who received mitomycin C did not complete the CRT within 42 days. The main cause was irregular visits, which were not related to toxicity.

It is difficult to compare the results of this study with those of other studies since all the patients involved in this study presented with locally advanced disease and showed poor adherence to treatment. Findings in most of the published studies involved patients from a high socio-economic cohort, and the doses of CRT administered to them were slightly different; RT dose ranging from 45 Gy to 54 Gy was given at 1.8 Gy per day and administered by intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) or 3D conformal RT for most studies from the USA.7,8,11,25 Higher doses of RT (60 Gy to 70 Gy) had also been used with split course RT.4 The chemotherapy was either mitomycin C, which had more adverse events, with doses of 10 mg/m2,7,8 12 mg/m2,21 or 15 mg/m2,6 or Cisplatin 25 mg/m6 to 75 mg/m2,23 with 5FU infusion 750 mg/m26,9 to 1 000 mg/m2/day for 4 to 5 days.4,7 However, the data included in this study do correspond with the findings of some other studies,7,11,17 in that no difference in RT duration between PLWH, who were on HAART, and HIVnegative patients was discernible. In contrast, other studies reported prolonged RT duration for PLWH despite being on HAART and most of the subjects had CD4 counts > 200 and suppressed VL,4,6 but these results should be interpreted with caution since the studies concerned are regarded as small (sample sizes ranging from 464 to 14217) retrospective studies.

The main limitations of this study are its small size, particularly the HIV-negative cohort, and the retrospective design which might point to selection bias. Comparison between toxicity grades was limited as toxicity grading was not documented for most patients. Interpretation is also hindered by the multiple chemotherapy regimens prescribed for the patients.

Conclusion

It appears from this study that HIV status had a limited influence on the duration of CRT. Although toxicity was a major problem associated with this type of therapy, it only contributed to approximately a third of the instances where therapy was delayed. Defaulting and poor attendance at the health facility were important factors contributing to this trend. Further studies that address socio-economic factors are recommended, as are greater efforts to educate the high-risk population comprised mainly of PLWH.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to the radiation oncology department at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital for hosting the study, and to Prof. Candy and Dr Kotsen for their support and review to this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding source

No funding was required.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand No. M160674.

ORCID

AR Zubi https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3578-3992

DJ Surridge https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2828-3773

REFERENCES

1. Shiels MS, Kreimer AR, Coghill AE, Darragh TM, Devesa SS. Anal cancer incidence in the United States, 19772011: distinct patterns by histology and behaviour. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(10):1548-56. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0044. [ Links ]

2. Shridhar R, Shibata D, Chan E, Thomas CR. Anal cancer: current standards in care and recent changes in practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):139-62.[https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21259. [ Links ]

3. Dandapani SV, Eaton M, Thomas CR, Pagnini PG. HIV-positive anal cancer: an update for the clinician. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;1(1):34-44. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2010.005. [ Links ]

4. Munoz-Bongrand N, Poghosyan T, Zohar S, et al. Anal carcinoma in HIV-infected patients in the era of antiretroviral therapy: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(6):729-35. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182137de9. [ Links ]

5. Meyer JE, Panico VJA, Marconato HMF, et al. HIV positivity but not HPV/p16 status is associated with higher recurrence rate in anal cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2013;44(4):450-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-013-9543-1. [ Links ]

6. Oehler-Jänne C, Huguet F, Provencher S, et al. HIV-specific differences in outcome of squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal: a multicentric cohort study of HIV-positive patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15):2550-7. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2348. [ Links ]

7. Grew D, Bitterman D, Leichman CG, et al. HIV infection is associated with poor outcomes for patients with anal cancer in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(12):1130-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000476. [ Links ]

8. White EC, Khodayari B, Erickson KT, et al. Comparison of toxicity and treatment outcomes in HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;40(4):386-92. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000172. [ Links ]

9. Hammad N, Heilbrun LK, Gupta S, et al. Squamous cell cancer of the anal canal in HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34(2):135-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0b013e3181dbb710. [ Links ]

10. Seo Y, Kinsella MT, Reynolds HL, et al. Outcomes of chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C for anal cancer in immunocompetent versus immunodeficient patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(1):143-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.046. [ Links ]

11. Wieghard N, Hart KD, Kelley K, et al. HIV positivity and anal cancer outcomes: a single-centre experience. Am J Surg. 2016;211(5):886-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.01.009. [ Links ]

12. Blazy A, Hennequin C, Gornet J-M, et al. Anal carcinomas in HIV-positive patients: high-dose chemoradiotherapy is feasible in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(6):1176-81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-0910-7. [ Links ]

13. Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. Anal carcinoma, version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(7):852-71. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2018.0060. [ Links ]

14. Weber DC, Kurtz JM, Allal AS. The impact of gap duration on local control in anal canal carcinoma treated by split-course radiotherapy and concomitant chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(3):675-80. [ Links ]

15. Ben-Josef E, Moughan J, Ajani JA, et al. Impact of overall treatment time on survival and local control in patients with anal cancer: a pooled data analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trials 87-04 and 98-11. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(34):5061-6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.29.1351. [ Links ]

16. Graf R, Wust P, Hildebrandt B, et al. Impact of overall treatment time on local control of anal cancer treated with radiochemotherapy. Oncology. 2003;65(1):14-22. https://doi.org/10.1159/000071200. [ Links ]

17. Martin D, Balermpas P, Fokas E, Rodel C, Yildirim M. Are there HIV-specific differences for anal cancer patients treated with standard chemoradiotherapy in the era of combined antiretroviral therapy? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2017;29(4):248-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2016.12.010. [ Links ]

18. Wang CJ, Sparano J, Palefsky JM. Human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, human papillomavirus, and anal cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2017;26(1):17-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soc.2016.07.010. [ Links ]

19. Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2017. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2018. Available from: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022017.pdf. Accessed 11 May 2019. [ Links ]

20. Ntombela XH, Sartorius B, Madiba TE, Govender P. The clinicopathologic spectrum of anal cancer in KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa: analysis of a provincial database. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(4):528-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2015.05.005. [ Links ]

21. Robertson B, Shepherd L, Abratt RP, Hunter A, Goldberg P. Treatment of carcinoma of the anal canal at Groote Schuur Hospital. S Afr Med J. 2012;102(6):559-61. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.5674. [ Links ]

22. James RD, Glynne-Jones R, Meadows HM, et al. Mitomycin or cisplatin chemoradiation with or without maintenance chemotherapy for treatment of squamous-cell carcinoma of the anus (ACT II): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, 2x2 factorial trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):516-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70086-X. [ Links ]

23. Ajani JA, Winter KA, Gunderson LL, et al. Prognostic factors derived from a prospective database dictate clinical biology of anal cancer: The intergroup trial (RTOG 98-11). Cancer. 2010;116(17):4007-13. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25188. [ Links ]

24. Mayosi BM, Benatar SR. Health and health care in South Africa - 20 years after Mandela. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(14):1344-53. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1405012. [ Links ]

25. Roohipour R, Patil S, Goodman KA, et al. Squamous-cell carcinoma of the anal canal: predictors of treatment outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(2):147-53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-007-9125-z. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

AR Zubi

Email: zbhmd@yahoo.com