Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Surgery

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5151

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2361

S. Afr. j. surg. vol.58 no.4 Cape Town dic. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2078-5151/2020/v58n4a3137

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Predictors of the need for surgery in upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a resource constrained setting: the Pietermaritzburg experience

T MbamboI; MTD SmithI; LC FerndaleI; JL BruceI; GL LaingII; VY KongI, III; DL ClarkeI, III

IDepartment of Surgery, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

IIPietermaritzburg Metropolitan Trauma Service, South Africa

IIIDepartment of Surgery, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: This review from a tertiary centre in South Africa aims to describe the spectrum and outcome of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) and identify risk factors for surgical management and death.

METHODS: This was a retrospective review of a prospectively entered database of all adults presenting with UGIB between December 2012 and December 2016. Demographics, presenting physiology, risk assessment scores, outcomes of endoscopy endo-therapy and surgery were reviewed. Comparisons were made between patients who required operative therapy and those who did not, and between survivors and non-survivors.

RESULTS: During the review period, 632 patients were admitted with suspected UGIB. Out of these, 406 (64%) had an identifiable potential source of bleeding and 226 (36%) had no identifiable potential source of UGIB. The latter were excluded from further analysis. Of the 406 patients with a potential source of haemorrhage, there were 249 males (61%) and 157 females (39%). Nine of these were expedited directly to the operating room and never underwent an endoscopy. Of the 397 (98%) who had upper endoscopy 107 (26%) had endotherapy. Forty-six patients (11%) required surgery. They had significantly higher shock index (SI), increased need for transfusion, higher international normalised ratio (INR) and higher serum lactate than the non-operative group. Nine patients went to the operating room without endoscopy. Of the 46 patients who required surgery, 37 underwent an attempt at endoscopic intervention. Transfusion and transfusion volume increased the probability of requiring a laparotomy (p = 0.015) and (0.003) respectively. The independent predictors of need for operation were a raised shock index or serum lactate and Forrest Ia and Ib ulcers. Thirty-nine patients died, giving a mortality rate of 9.6%; ten had a gastric ulcer and 16 had a duodenal ulcer. Survival was significantly higher in the non-operative group (93.1% versus 68.2%; p < 0.001). The odds ratio for mortality in the laparotomy group is 6.73, 95% CI (3.15-14.17). Receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis showed that the pre-endoscopic Rockall score (PER), total Rockall score (TR) and the SI were poor predictors of mortality.

CONCLUSION: Patients with UGIB in our setting are younger than in high-income countries (HIC) and a larger number fail endoscopic therapy and require open surgery. The mortality in this subset is very high. Detailed analysis of failed endo-therapy has the potential to reduce mortality.

Keywords: predictors, need for surgery, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, resource constrained setting

Introduction

The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery has pointed out that lack of access to safe, timely, and affordable surgical and trauma care (STC) is a global public health problem.12 STC is under-financed and under-resourced in upper middle-income countries (UMIC). A significant number of deaths could be avoided by better access to surgical curative services. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a common emergency worldwide managed by surgeons in the public sector in South Africa. Its management has evolved over the last forty years and the mainstay of treatment is no longer surgery but a combination of medical therapy and interventional endoscopy.1-5 Although the mortality rate for UGIB has been steadily improving in high-income countries (HIC), the situation in low- to middle-income countries (LMIC) and middle-income countries (MIC) remains unclear.1-5 Lack of formal data registries makes it difficult to track outcomes and the lack of access to endoscopy services, surgery and anaesthesia means that it can be expected that outcomes in LMICs and MICs will trail those in HICs. In addition, in LMICs and MICs disease profiles may differ to those in HICs.

This retrospective study from a busy tertiary centre in South Africa aims to describe the spectrum and outcome of the UGIB and to review and identify risk factors for failure of endoscopic control and for the need for surgical management. South Africa is classified as a UMIC, yet this classification is deceptive as there are vast discrepancies in wealth and access to care within the country. There is a two-tier health system with a well-resourced private sector serving the needs of up to twenty per cent of the population whilst the poorest eighty per cent rely on a poorly managed and dysfunctional state sector. The secondary aim of the study was to review the accuracy of the commonly used scoring systems to predict the need for surgery and to predict mortality.6-8

Methods

Clinical setting

Grey's Hospital is a tertiary hospital in Pietermaritzburg, the largest city in the west of the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) province. Grey's is the referral hospital for 19 district and three regional hospitals in western KZN that is predominantly rural with a population of around two million people. All the health districts in the western third of the province score poorly in almost all markers of wealth and income. Although three regional hospitals in western KZN provide endoscopy services, only Grey's Hospital has advanced endoscopic diagnostic and therapeutic facilities. In general, the endoscopic services available in the government sector in western KZN are inadequate to meet the burden of gastro-intestinal disease. Transfer times from rural hospitals to Grey's may be prolonged. All endoscopies at Grey's Hospital are recorded on the electronic medical registry, known as the hybrid electronic medical registry (HEMR). This has been functioning since 2012 and is covered by a class ethics approval from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) of UKZN.

Management of UGIB

All patients presenting to Grey's with an UGIB are assessed by the admitting surgical staff in the emergency department. They are resuscitated according to unit protocols, and then their risk factors are identified. Patients are classified as variceal or non-variceal. Stable patients without overt bleeding are managed medically and undergo upper endoscopy on the next available elective slate. During working hours, patients with overt bleeding are expedited to the endoscopy room. Variceal bleeding is controlled with rubber-band ligation and if this fails a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube is inserted. Ulcer related bleeding is controlled with a multi-modal approach consisting of injection therapy and endoluminal clip application. After-hours and in select cases, the patient is expedited to the operating room (OR) and once the airway is secured, endoscopy is attempted before embarking on surgery. The endoscopic modalities in the OR are more limited than in the endoscopy room (ER). All patients have a pre- and post-endoscopic Rockall score determined.

Methods

We undertook a retrospective review of a prospectively entered database in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. From the registry, all adults (age > 18) who presented with UGIB with a confirmed source of endoscopy were included. Baseline demographics, physiologic parameters (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate), laboratory results (lactate, haemoglobin, creatinine, leucocytosis), endoscopy findings, operative details, length of stay, and complications were collected. The following scores were used to quantify patients: the Rockall score and the shock index (SI) on presentation and the Forrest score at endoscopy. Rockall score assesses the likelihood of morbidity and mortality of the individual based on age, haemodynamic status, co-morbidities and endoscopic findings. A Rockall score < 3 is associated with good prognosis and > 3 associated with need for surgical intervention and high mortality. Forrest classification is an endoscopic risk stratification tool for rebleeding based on grade (grade Ia and Ib active UGIB, high risk, endo-therapy required, grade IIa, IIb and IIc possible cause of recent bleeding, intermediate risk and grade III no evidence of bleeding, low risk, no endotherapy). SI is defined as heart rate (HR) divided by systolic blood pressure (SBP) which helps assess the degree of hypovolaemic shock. A value SI > 0.9 and SBP < 90 mmHhg has been documented as associated with higher mortality and increased need for blood transfusion.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed. Comparison analyses between patients who required surgery and those who did not were performed as univariate comparisons between Rockall scores and Forrest classifications with Student's t-tests, chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Binary logistic regression was used to identify significant predictors of need for surgery and mortality. Receiver operator curve analysis (ROC) was performed to test the accuracy and sensitivity of the pre-endoscopic Rockall score (PER), the total Rockall score (TR) and the SI in predicting mortality in our sample. All analyses were performed using R version 3.5.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

During the review period, 632 patients were admitted with a suspected UGIB. Out of this cohort, 406 (64%) had an identifiable source of bleeding and 226 (36%) had no identifiable source of UGIB. These 226 were excluded from further analysis. Of the 406 patients with a proven source of haemorrhage, there were 249 males (61%) and 157 females (39%). Nine of these were expedited directly to the operating room and never underwent an endoscopy. Of the 397 who had upper endoscopy (98%), 107 had endotherapy (26%). In total 46 (11%) patients required surgery. The HIV status was unknown in 254 (62.6%), 74 (18%) were HIV positive and 77 (19%) were HIV negative. Just over half, 226 patients (55.9%) required a blood transfusion and 324 patients (80%) of these patients required more than two units of packed cells.

The source of haemorrhage was peptic ulcer disease (PUD) in 311 patients. Of these 304 (98%) had an upper endoscopy and 71 (23%) underwent endotherapy. Oesophageal varices were the source of haemorrhage in 58 patients, of which 57 (98%) had an upper endoscopy and 32 (55%) underwent endotherapy. In 37 patients the source of haemorrhage was not PUDs or oesophageal varices. Of this miscellaneous cohort, 36 (97%) patients underwent an upper endoscopy. Only four (11%) underwent endotherapy. Thirty-two (7.9%) patients required ICU admission. Thirty-nine patients died, giving a mortality rate of 9.6%.

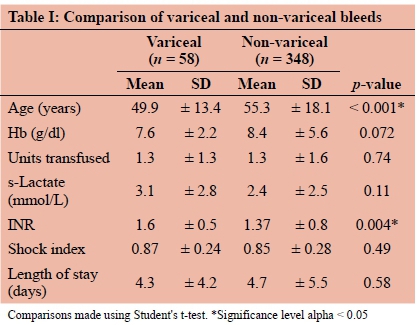

Variceal bleeding compared to peptic ulcer bleeding

There were 58 patients with variceal bleeds. They had a mean age of 47 years (range 24-77) and mean serum haemoglobin of 7.6 g/dl on presentation. The median number of endoscopic attempts to control bleeding was 1.0 (0-3). The patients with non-variceal bleeds were on average five years older than those with variceal bleeds with a mean age of 55 years (p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in presenting haemoglobin level or transfusion need. The variceal bleed group had higher international normalised ratios (INRs) compared to the non-variceal group (1.6 and 1.4 respectively; p = 0.004). Table I compares the variceal and non-variceal groups.

Surgery

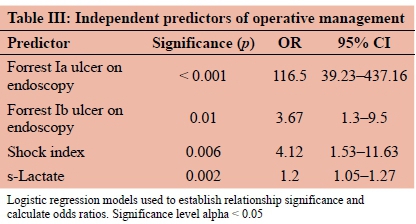

Forty-six patients (11.3%) underwent surgery. The group that required surgery had a higher percentage of smokers (34.1% versus 22.4%) and lower incidence of liver disease (4.5% versus 17.4%), though these differences were not significant. The operative group had significantly higher SI, increased need for transfusion, higher INR and higher serum lactate than the non-operative group. Table II compares the physiology of the operated and non-operated groups. The probability of requiring a laparotomy for a patient who also required transfusion was 14% (p = 0.015). The odds of requiring a laparotomy increased by 29% with each unit of packed cells transfused (0.003). Nine patients were expedited directly to the OR without an endoscopy. In 37 patients, endoscopic control had been attempted within the same admission. The independent predictors of need for operation were Forrest Ia and Ib ulcers on endoscopy, raised SI and raised serum lactate. These are quantified in Table III.

The pre-endoscopic and post-endoscopic Rockall score did not predict need for surgery in our cohort.

Mortality

Three hundred and sixty-seven (90.4%) patients survived and 39 died, giving a mortality rate of 9.6%. The survival rate was higher in the non-operative group (93.1% versus 68.2%; p < 0.001). The mortality for the variceal bleed group and the PUD group were 10.3% and 8.7% respectively. In the operative group there was no statistically significant difference in the mortality rate between those who had a preceding upper endoscopy and those who did not. Those patients who had a laparotomy were 6.73 times more likely to die than those who did not have surgery (95% CI 3.15- 14.17). Table IV compares the patients who died with the patients who survived.

Independent predictors of mortality in the variceal bleed group were comorbid diabetes mellitus (OR 6.1, 95% CI 0.9-42.4; p = 0.0413) and laparotomy (21.2, 95% CI 1.45- 756.8; p = 0.014).

In the non-variceal group, the need for laparotomy (OR 6.1, 95% CI 2.7-13.6; p < 0.001), presence of a Forrest Ia ulcer (OR 116.5, 95% CI 39.2-437.2; p < 0.001) and increasing SI were independent predictors of mortality. A SI < 0.75 was predictive of mortality with a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 41% (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.64, p = 0.02).

ROC analysis was performed to evaluate the accuracy of the PER, TR and the SI in predicting mortality in our sample. Both PER and TR did not predict mortality with any significance in logistic regression models. The PER had an AUC of 0.6 (p = 0.005) but a sensitivity of only 12.8% for a score exceeding 3 points. Figure 1 shows the ROC curves.

Discussion

Acute UGIB remains a common emergency throughout the world.2-5 However, it has changed from being a surgical emergency to a medical one in most HICs. In the United Kingdom (UK), UGIB has a reported incidence of between 80-110 per 100 000 in the population and has been the subject of two nationwide audits a decade and a half apart, in 1993 and 2007 respectively. Over that period, the crude overall mortality from acute UGIB improved from 14% to 10% and the need for surgery decreased drastically from 6.7% to 1.9%. However, in patients who require surgery for UGIB in HICs, the mortality rate ranges from 10-20%.25 The patients in our centre are on average a decade younger than those in the UK. Although our overall mortality is similar to that reported from the UK, the need for surgery in our setting is significantly higher (10% vs 1.5%). In addition, the mortality rate for patients undergoing surgery was high (32%). A total of 33 patients rebled and from that 10 (30.3%) required surgical management and all subsequently died. Their hospital stays ranged from 1-25 days with predominantly duodenal and gastric ulcers. This suggests that there is a discrepancy in outcome for this disease across the globe and that this needs to be interrogated.

In addition, the spectrum of patients presenting in our environment with life significant UGIB is much younger than in HICs. A major contribution to this outcome is almost certainly lack of access to safe and effective endoscopic services. Endoscopic therapy has become the mainstay of treatment of UGIB over past 10 years. There are a multitude of adjuncts such as injection therapy, haemostatic clips, heater probes, bipolar electrocautery and argon laser therapy which are used as part of a multimodal strategy. In our own environment, access to all these modalities is inconsistent and hampered by lack of consumables and by the inconsistent availability of endoscopic expertise. Whilst there is access to emergency endoscopy around the clock, the after-hour service is not of the same calibre as the working hours service. Endoscopy after hours is performed in the OR rather than the ER and skilled dedicated endoscopic nursing is not always available. In addition, there is limited access to the therapeutic endoscopic modalities in the OR. Previous work in KZN has suggested that the endoscopy services in the province are insufficient to meet the demand for both diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy.9 This translates into poorer outcomes for a number of luminal gastrointestinal diseases, including UGIB. A concerted strategy is required to develop an appropriate plan for endoscopic services in the province.

It would appear that the need for surgery to control an UGIB is an ominous sign. All such patients need urgent processing and enhanced care and intervention in an effort to reduce the need for surgery, as the outcome for surgery is not good. Reliable predictors of the need for surgery may help triage and stratify such patients. Our data suggests that SI, serum lactate and the presence of a Forrest Ia and Ib ulcer on endoscopy are independent predictors for the need for operative management or improved endotherapy. The Rockall score did not predict the need for surgery or the likelihood of death in our cohort. The Rockall score is very dependent on age. In our series almost all our patients were less than sixty years of age and this may well impact on the predictive ability of the Rockall score.68

Conclusion

Patients with UGIB in our setting are younger than in HICs and a larger number fail endoscopic therapy and require open surgery. The mortality in this subset is very high. Efforts should be made to reduce the need for surgery in these high-risk patients. A possible mechanism to effect this is to use our high risk predictors of the need for surgery to guide the need for endotherapy, and to monitor the effect of improving access to advanced therapeutic endoscopy across the whole platform, including the after-hours service.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding source None.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) of UKZN: BE 207/09, 221/13.

ORCID

T Mbambo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5548-6891

MTD Smith https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6954-153X

LC Ferndale https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1644-3124

JL Bruce https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8666-4104

GL Laing https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8075-0386

VY Kong https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2291-2572

DL Clarke https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8467-1455

REFERENCES

1. Meara JG, Greenberg SL. The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery Global surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare and economic development. Surgery. 2015 May;157(5):834-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2015.02.009. [ Links ]

2. Clarke MG, Bunting D, Smart NJ, Lowes J, Mitchell SJ. The surgical management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a 12-year experience. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):377-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.05.008. [ Links ]

3. Alatise OI, Aderibigbe AS, Adisa AO, et al. Management of overt upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a low resource setting: a real world report from Nigeria. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014 Dec 10;14:210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-014-0210-1. [ Links ]

4. Wang J, Cui Y, Wang J, et al. Clinical epidemiological characteristics and change trend of upper gastrointestinal bleeding over the past 15 years. 2017 Apr 25;20(4):425-31. [ Links ]

5. Moledina SM, Komba E. Risk factors for mortality among patients admitted with upper gastrointestinal bleeding at a tertiary hospital: a prospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017 Dec 20;17(1):165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-017-0712-8. [ Links ]

6. Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38(3):316-21. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.38.3.316. [ Links ]

7. British Society of Gastroenterology Endoscopy Committee. Non-variceal upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: guidelines. Gut. 2002:51(Suppl 4):iv1-6. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.51.suppl_4.iv1. [ Links ]

8. Vreeburg EM, Terwee CB, Snel P, et al. Validation of the Rockall risk scoring system in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 1999:44(3):331-5. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.44.3.331. [ Links ]

9. Loots E, Clarke DL, Newton K, Mulder CJ. Endoscopy services in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, are insufficient for the burden of disease: is patient care compromised? S Afr Med J. 2017 Oct 31;107(11):1022-5. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i11.12484. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Corresponding author

email: mbambot@gmail.com