Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Surgery

On-line version ISSN 2078-5151

Print version ISSN 0038-2361

S. Afr. j. surg. vol.58 n.3 Cape Town Sep. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2078-5151/2020/v58n3a3378

VIDEO CASE REPORT

Pancreas preserving duodenectomy for duodenal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis

J LindemannI, II; JEJ KrigeI; JonasI

ISurgical Gastroenterology Unit, Division of General Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, Groote Schuur Hospital, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIDepartment of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, Missouri, United States of America

ABSTRACT

Duodenal polyposis is common in familial adenomatous polyposis with a significant associated lifetime risk of cancer. Screening and regular surveillance is recommended, guided by the Spigelman stage. Pancreas preserving duodenectomy (PPD) is the preferred operation in patients needing removal of the whole duodenum. This presentation demonstrates the technique of PPD with particular emphasis on the resection and ampullary reconstruction. Initial early feeding tube placement through the cystic duct stump into the duodenum enables identification of the papilla and pancreatic duct as well as subsequent dissection. Separate trans-anastomotic pancreatic and biliary stents facilitate creation and patency of the pancreato-biliary anastomosis. The operation has similar outcomes compared to pancreaticoduodenectomy, however, the anatomical reconstruction allows for postoperative surveillance.

Case description

A 32-year-old female with known familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) was referred for further management of duodenal and proximal small bowel polyps. She had undergone a total proctocolectomy with an ileoanal pouch anastomosis at 18 years of age. She subsequently required resection of a large abdominal wall desmoid tumour with complex reconstruction for which she also received a significant dose of radiation. At the time of the operation it was noted that she had coeliac axis desmoid changes and she received treatment first with Sulindac and then Arcoxia with good response. She then developed gastric and small bowel polyps diagnosed on routine screening. Evaluation of the polyps included a PilCam and push enteroscopy which revealed adenomas as far as 40 cm from the ligament of Treitz with an estimated 100 small bowel polyps. Biopsies showed tubular adenomas with low grade dysplasia, consistent with Spigelman stage III. Given the number and extent of adenomas, the decision was made to perform a pancreas preserving duodenectomy (PPD).

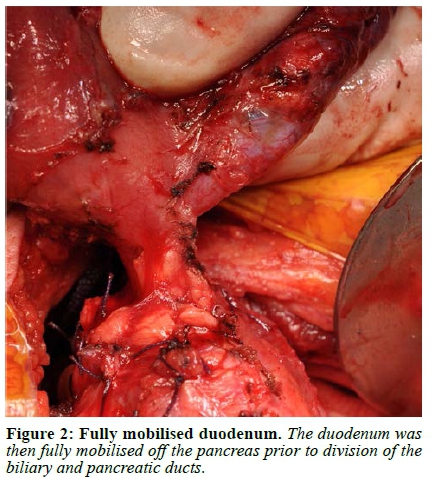

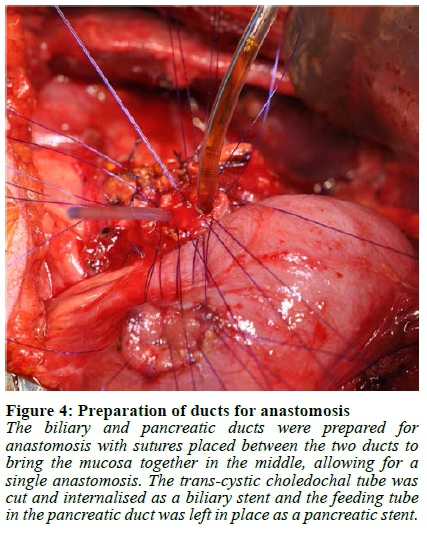

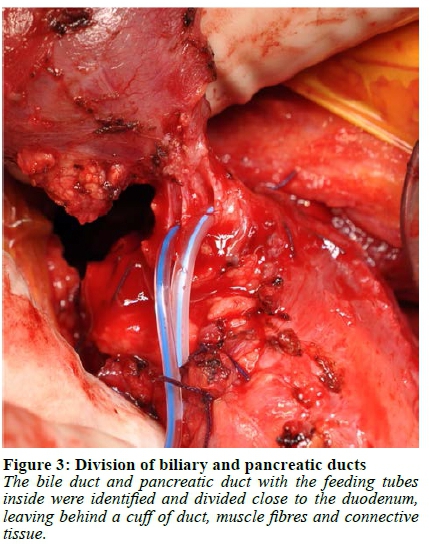

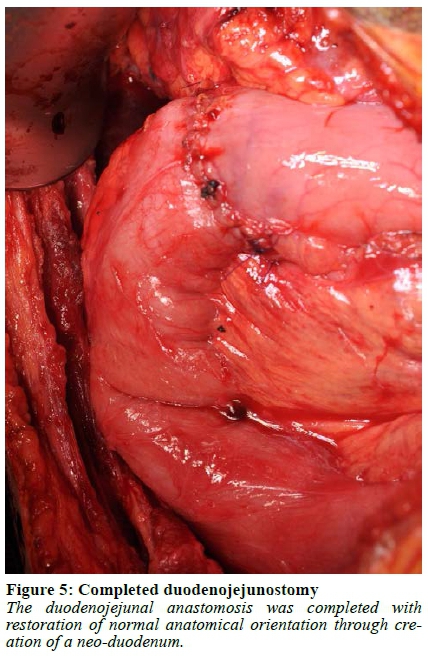

Abdominal access was gained through a subcostal right upper quadrant incision followed by lysis of extensive adhesions. The stomach and first 120 cm of small bowel were mobilised, and a Kocher manoeuvre was performed to mobilise the duodenum and head of the pancreas. The duodenum was then divided 1 cm distal to the pylorus and the jejunum was divided 40 cm from the ligament of Treitz. A cholecystectomy was performed followed by passing a 12 F feeding tube through the cystic duct stump into the duodenum to identify the papilla. A duodenotomy was made and a feeding tube was used as a guide to identify the pancreatic duct, into which a 10 F feeding tube was subsequently placed (Figure 1, Video 1). Once the duodenum was fully mobilised off the pancreas, the bile duct and pancreatic duct with the feeding tubes inside were identified and divided close to the duodenum leaving behind a cuff of duct, muscle fibres and connective tissue (Figure 2, 3, Video 1). If an accessory pancreatic duct is identified during dissection it would be ligated at this stage. The ducts were then prepared for anastomosis, with sutures placed between the two ducts to bring the mucosa together in the middle, creating a single duct (Figure 4, Video 1). The feeding tube through the cystic duct stump was cut and internalised as a biliary stent and a portion of the feeding tube in the pancreatic duct was left in place as a pancreatic anastomotic stent. The anastomosis was performed using a 5/0 monofilament absorbable suture. An end-to-end duodenojejunostomy was then performed, restoring normal anatomical orientation through creation of a neo-duodenum using jejunum (Figure 5, Video 1). This technique leaves very little duodenal mucosa behind, located just distal to the pylorus in an easy-to-reach area for surveillance. Additionally, this anatomical orientation as opposed to the hepaticojejunostomy after a pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) allows for easier future surveillance of the proximal small bowel via push enteroscopy.

The patient tolerated the procedure well with no intra-operative complications. She developed severe superficial wound sepsis, aggravated by her previous high dose abdominal wall radiation. At her first postoperative visit the wound had almost completely healed, and she reported feeling well. Routine surveillance began three months postoperatively with regular gastroscopy and push enteroscopy. The histology report showed numerous tubular adenomas throughout the duodenum and proximal jejunum, predominantly sessile, with low grade dysplasia of the epithelial lining of the tubular polyps. There was no evidence of high grade dysplasia or invasive malignancy.

Discussion

FAP is caused by an autosomal dominant mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene and equally affects men and women.1 FAP is defined by the presence of greater than 100 colorectal polyps with a near 100% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer (CRC).2 There are several extracolonic manifestations of FAP, the most common being upper gastrointestinal tract polyps.2 Duodenal polyposis occurs in 30-70% of patients with an associated 5% lifetime risk of developing duodenal carcinoma, which is the second most common cause of death in FAP patients after CRC.1 The second and third portions of the duodenum as well as the periampullary region are most commonly affected.2 The Spigelman classification, used to stage disease severity, correlates with the risk of duodenal malignancy and is calculated by awarding points for the number and size of polyps, as well as the histological type and the presence of dysplasia on biopsy.3 Because neither chemoprophylaxis nor pharmacologic treatment have been shown to be of benefit in reducing or preventing progression of duodenal polyposis, endoscopic or surgical intervention becomes necessary.2 For Spigelman stage I endoscopic intervention is indicated, usually with polyp removal by endoscopic ampullary resection or mucosectomy.2 Similarly, in Spigelman stage II disease, endoscopic intervention is used.2 For patients with Spigelman stage IV or in failed endoscopic intervention for lower Spigelman stages, surgery is recommended.2 Stage III patients are assessed on a case-by-case basis for either endoscopic therapy or surgical resection. In selected patients with Spigelman stage III, as in this patient, surveillance and endoscopic management can be difficult when faced with a multitude of polyps in which case surgery may be the better treatment option. The surgical options include trans-duodenal local resection (polypectomy or ampullectomy), a PPD or PD.2 Local surgical treatment has the disadvantage of leaving most of the duodenal mucosa which is susceptible to developing polyps and malignancy in the future. In individual cases, it is important to weigh the risk of developing duodenal adenocarcinoma against the risk of surgery and its associated complications.

Both PPD and PD result in low rates of recurrence but have significant morbidity. Although duodenal polyposis in FAP is the most common indication for PPD, there are few small case series in the published literature.47 These studies show early postoperative complication rates comparable to a PD with similar rates of postoperative pancreatic fistulae, bile leaks, wound and intraabdominal infections, and re-laparotomy rates.47 Reported long-term outcomes are comparable and patients are able to tolerate a normal diet while maintaining a healthy weight and resume a preoperative level of physical activity.4,7 Polyp recurrence, although rare, does occur, and warrants lifelong surveillance after a PPD.2 Importantly, a PPD is not an oncologic operation and if cancer is suspected, a PD is the appropriate surgical choice.2

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding source

None.

ORCID

J Lindemann https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8089-0191

JEJ Krige © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7057-9156

E Jonas © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0123-256X

REFERENCES

1. De Vos tot Nederveen Cappel WH, Järvinen HJ, Björk J, et al. Worldwide survey among polyposis registries of surgical management of severe duodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 2003;90:705-10. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.4094. PMID: 12808618. [ Links ]

2. Brosens LAA, Keller JJ, Offerhaus GJA, Goggins M, Giardiello FM. Prevention and management of duodenal polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2005;54:1034-43. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000000010. PMID:24161962. [ Links ]

3. Spigelman AD, Talbot IC, Penna C, et al. Evidence for adenoma-carcinoma sequence in the duodenum of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. The Leeds Castle Polyposis Group (Upper Gastrointestinal Committee). J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:709-10. PMID: 7962621. [ Links ]

4. Sarmiento JM, Thompson GB, Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy for duodenal polyposis. Arch Surg. 2002;137(5):557-62, discussion 56263. PMID: 11982469. [ Links ]

5. Penninga L, Svendsen LB. Pancreas-preserving total duodenectomy: a 10-year experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18(5):717-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-011-0382-9. PMID: 21476063. [ Links ]

6. Chung RS, Church JM, van Stolk R. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy: Indications, surgical technique, and results. Surgery. 1995;117(3):254-9. PMID: 7878529. [ Links ]

7. De Castro SMM, Van Eijck CHJ, Rutten JP, et al. Pancreas-preserving total duodenectomy versus standard pancreatoduodenectomy for patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and polyps in the duodenum. Br J Surg. 2008;95(11):1380-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6308. PMID: 18844249. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Email: eduard.jonas@uct.ac.za

Video available online: http://sajs.redbricklibrary.com/index.php/sajs/article/view/3378