Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Surgery

On-line version ISSN 2078-5151

Print version ISSN 0038-2361

S. Afr. j. surg. vol.58 n.3 Cape Town Sep. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2078-5151/2020/v58n3a3066

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Bioring® gastric banding for obesity in a private South African hospital

GADewarI; RJ UrryII; S CliffordIII; Μ KatsapasIV; L StevensI; Α KloppersIII

IRetired

IIGeorge Mukhari Hospital, South Africa

IIILife Glynnwood Hospital, South Africa

IVPrivate Practice, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Obesity is a significant health problem in South Africa. Surgery is the most effective means of durable weight loss for the morbidly obese. Of the surgical options, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding is the most controversial. We aimed to assess a single surgeon's experience with a specific band.

METHODS: A retrospective observational study of a continuous cohort of laparoscopic adjustable gastric Cousin Bioring® band placements from a single private South African hospital was conducted. Three hundred and fifty bands were placed in 347 patients, 75% were female. Variables analysed were BMI obesity class, comorbidities, weight loss, diabetes resolution, adherence to aftercare, patient satisfaction, complications and death.

RESULTS: Outcomes were assessed in 343 patients (4 patients lost to follow-up). The mean follow-up was 39 months (IQR 29-66 months). The mean preoperative BMI was 43.3 kg/m2 (IQR 37.4-47.6 kg/m2). Most weight loss occurred in the first year, and 66% achieved > 40% excess weight loss. Resolution of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes occurred in 56.4% and 89.8% of patients respectively. Increasing age (p = 0.002), class 3 obesity (p < 0.001) and suboptimal aftercare (p < 0.001) were associated with failure. One patient developed band erosion and 40 developed band slippage, 34 of whom underwent secondary surgery (32 removals, 2 revisions). All complications were grade I-III. There was no high grade complication, and no death.

CONCLUSIONS: Bioring® gastric banding achieved moderately good weight loss and resolution of type 2 diabetes with a low complication rate. BMI > 60 and suboptimal aftercare predicted poor outcome.

Keywords: gastric banding, South Africa

Introduction

Obesity poses a health challenge and South Africa is experiencing an epidemic across its ethnic spectrum.1,2 A 2013 analysis reported 42% of South African adult females as obese, and close to 70% as either overweight (BMI 2530 kg/m2) or obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2).3

Surgery is recognised as the most effective and durable treatment.4-7 In the context of South Africa's national healthcare policy, weight loss surgery is not deemed a priority in the state sector with tertiary institutions running very limited programmes,8 and only specific medical aids funding the surgery in the private sector.9 Although all weight loss procedures are now regarded as safe,7,10,11 referral for surgery is often tardy because of perceived surgical risk and cost.

In South Africa, bariatric surgery centres of excellence have been established and accredited. These centres favour laparoscopic procedures that create stapled suture lines to construct a restrictive operation, e.g. sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or a restrictive and malabsorption operation, e.g. Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB). In keeping with recent international trends, they do not perform gastric banding. They base this practice on reports of large databases and observational cohorts showing both sustained weight loss and improvement in diabetes, especially with RYGB.10-13 In contrast, long-term results particularly with the Lap-Band® procedure in Australia have also demonstrated sustained weight loss with comorbidity resolution and low complication rates.7,14,15 Band design has also evolved to ease insertion and removal, and to reduce the likelihood of migration and erosion.16,17

In this report, mid-term outcomes of a South African single-hospital consecutive series of laparoscopic Bioring® bands are documented. The Bioring® band was chosen because of its ease of insertion and removal, and because it exerts a low pressure even when full.17 The question was asked as to whether this band might be effective both in terms of weight loss and resolution of diabetes, and whether it has a low complication rate.

Methods

The records of patients from a database of all patients scheduled for laparoscopic Bioring® banding between January 2011 and July 2018 at Life Glynnwood Hospital were reviewed. Alternative weight loss interventions were not offered during this period.

Patient selection and preoperative assessment

Patients were required to be obese with a BMI 3040 kg/m2 with one or more comorbidities or a BMI > 40 kg/m2 with or without comorbidities. Patients were categorised by obesity class.1820,7 Patients who had undergone previous hiatal hernia repair were excluded. Preoperative evaluation included screening on history for diabetes, dyslipidaemia, arthritis, hypertension, coronary artery disease and depression, polycystic ovary syndrome and medicinal usage. Diabetes and prediabetes were diagnosed on the basis of HbA1C levels. Serum lipid profiling and renal and liver function testing were performed selectively. Fatty liver and asymptomatic gallstones were diagnosed on ultrasound and liver function tests. Sleep apnoea was diagnosed based on continuous positive airway pressure machine usage or prior sleep laboratory referral. Preoperative nutritional assessment was made by dietician who also oversaw post-procedural nutritional advice. Patients with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms underwent evaluation to exclude a large hiatus hernia. After initial workup was complete, the surgeon conducted informed consent counselling which included a comprehensive procedure video.

Technique

All patients followed a preoperative fatty liver shrinkage diet.21 They received combined mechanical and pharmacological venous thromboembolism prophylaxis22 and a 2 g dose of prophylactic cefazolin. Bioring® bands were placed above the posterior omental sac by the pars flaccida route23 using 4 ports, a Nathanson® liver retractor, and an articulated band pull through instrument. Pouch size was estimated visually and made as small as possible. Band size (10 ml, 15 ml or 20 ml) was also judged visually so as to be snug, but not tight. Three non-absorbable gastro-gastric sutures were interspaced between the greater and lesser stomach curvatures to prevent anterior slippage.

Aftercare

First band fills were made one month after surgery. Initial fill volumes were made according to the patient's band size (3 ml for 10 ml band, 4 ml for 15 ml band, and 5 ml for 20 ml band). Aftercare visits every three months during the first postoperative year, and every six months thereafter were emphasised as being mandatory. Reminder emails and text messages were used to minimise aftercare defaults. Subsequent volume adjustments were based on weight loss progress and consideration of side effects. Neither fluoroscopy nor band manometry was used to guide fill volumes.24,25 The dietician emphasised that patients should eat slowly, as their band aimed to produce early satiety to reduce energy intake, without inducing symptoms of obstruction.26,27

Data collection

Data retrieved for all patients included demographic details, comorbidities, and medicinal usage. Early (within a month) and late complications were noted. Complications were graded according to Dindo Demartines Clavien Grading.28 Operative mortality was defined as death precipitated by surgery and occurring within thirty days of surgery. Follow-up information was obtained from three months prior to the closure of patient accrual to nine months after closure. All information was obtained by the lead author, either face to face, telephonically, or by email. At last contact, weight, wellbeing, satisfaction evaluation, and number of months elapsed since insertion were recorded. The primary endpoint was achievement of > 40% excess weight loss (EWL). The secondary endpoint was the resolution or amelioration of prediabetes/diabetes. Prediabetes resolution meant reversion of HbA1C level29 to normal, and diabetes resolution cessation of anti-diabetic medication/s.30,31 Inadequate aftercare was defined as fewer than three visits within the first year, and incomplete aftercare as no visit/s beyond the first year. Aftercare was labelled as suboptimal if it was either inadequate or incomplete. Lost to follow-up was defined as uncontactable at the conclusion of the study period. Patients resident outside of South Africa or more than 400 km away were entered as geographically remote.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 (IBM, USA). Means were compared using the t-test for equality of means, both in paired and independent samples. Pearson's χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables. If the projected frequency, assuming a true null hypothesis, in a cell of a two-by-two table was less than five observations, we used Fisher's exact test. Multiple univariate logistic regressions were used to determine the odds ratios for failure. A p-value < 0.05 (5%) was considered statistically significant.

Results

In 347 of 348 consecutive patients, 350 Bioring® bands were placed. Band placement was not achieved in one patient (a male with prohibitive hepatomegaly and BMI 75.1 kg/m2) and 3 patients received a second band. Of the 348 patients, 262 (75.3%) were female and 86 (24.7%) were male. The mean age was 40.6 years (SD ± 10.6; IQR 33-48 years). The mean BMI at entry was 43.3 kg/m2 (IQR 37.447.6 kg/m2). The mean starting weight was 123.0 kg (IQR 103.0-138.4 kg). The breakdown of patients by obesity class and comorbidity is detailed in Table I.

Previous procedures and synchronous procedures

Four patients had bands placed several months after reversal of a previous open jejunoileal bypass operation. One patient had undergone an open and a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Synchronous procedures were performed in 39 patients: an umbilical hernia repair, a cholecystectomy and 36 posterior diaphragmatic crural plications for small hiatal hernias.

Aftercare attendance and end of study follow-up

The mean duration since surgery was 39.1 months (IQR 2966 months). End of study follow-up (158 face-to-face, 39 email, 126 telephonic, and 20 text message) was achieved in 343 of the 348 patients (98.5%). Four patients failed to both adequately attend during their first postoperative year and were lost to follow-up. Aftercare attendance was inadequate in 38 patients (11.1%) and incomplete in 17 patients (5.0%). Of the 55 (16.1%) with suboptimal aftercare, 23 (41.8%) were geographically remote. This association was significant (p = 0.018).

Outcomes

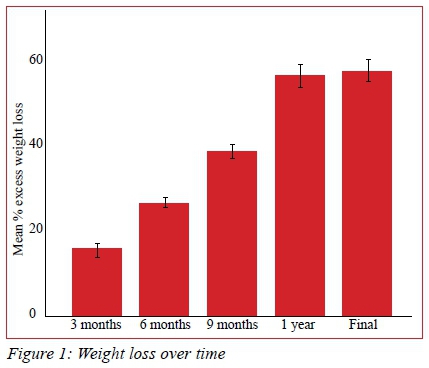

The primary endpoint of > 40% EWL was achieved in 228 (66.3%) patients. Patients' weight loss progress is represented in Figure 1. There -was no significant difference in mean weight loss at 1 year compared to the entire follow-up period (p = 0.150).

Prediabetes resolved in 44 of 49 patients (90%) and diabetes in 44 of 78 patients (56%). One patient, whose diabetes resolved at 15 months, relapsed at 65 months. No insulin dependent diabetic was able to discontinue insulin. There was a significant association between achieving successful weight loss and resolution of diabetes (p < 0.001).

Complications, deaths and secondary surgeries

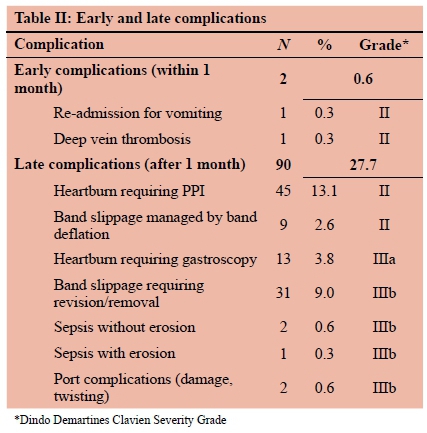

There were no operative deaths. Three patients died during the follow-up period. Their deaths were due to H1N1 influenza pneumonia, motor vehicle accident and breast cancer. Postoperative complications are detailed in Table II. No grade IV or V complication occurred.

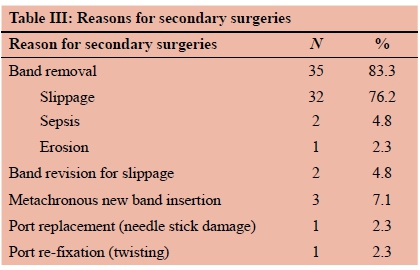

Band slippage occurred in 40 patients (11.6%) and 32 bands were removed for slippage. Two slipped bands were revised. A single patient developed band erosion and made an uneventful recovery after it was removed laparoscopically. Two infected (skin derived methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus) bands required removal. In total, 37 bands were removed, and secondary surgery was necessary in 44 patients (12.8%). The band explanation rate was 1.5% per annum. The mean time to removal was 32.8 months (range 7-73 months). Three patients (0.87%) had second bands placed several months after having had a first band removed for slippage. Two failure patients underwent band removal with conversion to a different procedure by other surgeons (RYGB and SG respectively). Four patients became pregnant with a band in situ. One suffered a spontaneous abortion at two months of pregnancy. The remaining three patients' pregnancies were uncomplicated. One patient required her band to be deflated for the duration of her pregnancy.

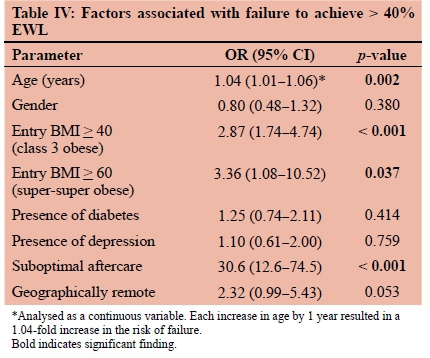

Factors associated with outcome

Factors associated with failure are detailed in Table IV. Of the 348 patients, 116 (33.3%) failed to achieve and 232 (66.7%) achieved > 40% EWL. Mean age was significantly different between failure (mean 43.1; SD ± 10.1 years) and success (mean 39.5; SD ± 10.3 years) groups (p = 0.002). Each increase in age by 1 year resulted in a 1.04-fold increase in the likelihood of failure (p = 0.002). In addition, class 3 obesity (p < 0.001) and poor aftercare (p < 0.001) were significantly associated with failure.

Discussion

This study showed that > 40% EWL was achieved in 67% of Bioring® banded patients. We view this as moderate success. Although band type and duration of follow-up differ between studies, fourteen out of seventeen series111432-46 identified by O'Brien et al.15 documented similar success. It also showed that close to 50% of type II diabetics were able to discontinue anti-diabetic medications. This is superior to the 10% reported by Niville et al.,47 but below the 73% achieved by Dixon et al.48,49 Not one of 8 insulin dependent diabetics was able to discontinue insulin. As in other series10,15,30,39,50-56 the procedure proved to be very safe, and complications were infrequent and all low grade.

We operated on 40 (11.5%) class 1 patients, all of whom had at least one comorbidity. Although inclusion of class 1 patients differs from NICE19 and NIH20 guidelines, it accords with other published recommendations,7 and with a prospective trial which compared results of banding versus best medical therapy in class 1 obesity.50

Band slippage occurred in 40 patients (11.5%), of which 39 manifested beyond a year. A distinction between pouch overstretch and stomach slippage was not apparent. All patients presenting with food intolerance (regurgitation of all intake) were labelled as having slippage. This is a liberal definition, which to a degree likely explains the high prevalence in this series compared with that of Giet et al. who reported a mere 1.7% slippage rate.57 Most (34 of 40, 85%) slippage patients in this series came to secondary surgery. Thirty-two slipped bands were removed, and 2 were revised. Revision entailed unlocking the band, removing previous gastro-gastric sutures, pulling down the enlarged pouch, re-locking the band, and new anterior gastro-gastric suturing. Although technically more demanding and less predictable than removal in relieving eating intolerance, we believe that revision should be considered if the patient's general condition is satisfactory. Beitner et al. viewed revision as part and parcel of band maintenance,56 and Niville et al. were able to revise all their slipped bands without device removal.47 It is apparent, however, that a foolproof anti-slip method (better than anterior gastro-gastric suturing) would be beneficial. Our band attrition rate was just under 1.5% per annum. It is likely that with longer follow-up58 numbers will increase.

Band erosion is rare,59-61 and the rate appears to vary according to band type. We encountered only one patient (1/343, 0.29%). His band eroded at 2 years. This compares with Niville et al. who documented a 1.66% erosion rate in a Lap-Band® series,61 and with 0.04% in the Bioring® series of Giet et al.57 An outlier Lap-Band erosion prevalence of 33% was reported by Himpens et al.37 We attribute our low erosion prevalence to the low pressure exerted on the gastric wall and the bellows-like action on inflation of the Bioring® band.17

Increasing age, super-super obese status, and suboptimal aftercare were identified as predictors of failure. Geographic remoteness contributed to suboptimal aftercare but was not an independent predictor of failure. In future, we aim to exclude patients of BMI > 60 kg/m2, patients over 65 years of age, and remote patients. These predictors of failure have not previously been reported. Varban et al.54, however, did observe that BMI < 40 kg/m2 correlated with greater success in their series.

A decade ago, gastric banding was the worldwide leading weight loss operation.52 Nowadays, SG holds this position.62-65 In our opinion, the durability of SG needs further confirmation. To date only 3 SG series have reported results beyond ten years.62-64 A contributing factor to banding decline is that aftercare has to be intensive and ongoing, and this is a demand on resources. Aftercare is best if it is protocol driven. Non-reporters need to be repeatedly summoned to attend. In our series, suboptimal aftercare was a significant predictor of failure (see Table IV). Also, certain band types (Lap-Band® and Bioring®) likely have fewer complications than others. Despite these considerations, it remains difficult to explain today's divergent opinions on banding's merits, especially across and within countries. For example, most of the US,66 Switzerland,46 Scandinavia41 and Israel67 have abandoned banding. Yet pockets of ongoing resolute support continue within Australia,15 England,57 Italy,39 Belgium47 and the US.53,68

This study has weaknesses. Its retrospective nature precluded better characterisation of comorbidities, and aftercare was suboptimal in 16%. Routine physician and psychologist assessment is now mandatory in our assessment. In addition, the median three-year follow-up period is too short to determine the long-term efficacy of this procedure.

The study's strengths include that analysis was on an intention to treat basis, that placement technique and bandtype were standardised, and that follow-up was high (343 of 347 patients; 98.5%). In addition, factors associated with failure were identified that can guide the practice of those using lap banding.

Conclusions

Bioring® banding is safe. It achieves moderately good weight loss and resolution of non-insulin dependent diabetes in the mid-term. It is not an ideal option for all patients. We have identified some patients who are best referred for a different procedure. Although slippage remains problematic, Bioring® banding still has a place in bariatric surgical options particularly in those with a BMI < 40 kg/m2.

Acknowledgements

Miss Dorcas Tshabalala (theatre sister) and Mrs Denise Louw (Cousin Bioring® product specialist).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained for this retrospective observational study from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Council (Protocol no: M180804).

ORCID

RJ Urry https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3214-532X

REFERENCES

1. Kruger HS, Puoane T, Senekal M, Van der Merwe MT. Obesity in South Africa: challenges for government and health professionals. Public Health Nutr. 2005 Aug;8(5):491-500. PMID: 16153330. [ Links ]

2. Van der Merwe MT, Pepper MS. Obesity in South Africa. Obes Rev. 2006 Nov;7(4):315-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00237.x. PMID: 17038125. [ Links ]

3. Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014 Aug 30;384(9945):766-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. PMID: 24880830. [ Links ]

4. Warren M, Beck S, Rayburn J, et al. The state of obesity 2018: better policies for a healthier America. Trust for America's Health. September 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 15]. Available from: https://www.tfah.org/report-details/the-state-of-obesity-2018/. [ Links ]

5. Lubbe J. Obesity and metabolic surgery in South Africa: review. The South African Gastroenterology Review. 2018;1:23-8. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-e16fec970. [ Links ]

6. Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg. 2013 Apr;23(4):427-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0864-0. PMID: 23338049. [ Links ]

7. O'Brien PE. Controversies in bariatric surgery. Br J Surg. 2015 May;102(6):611-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9760. MID: 25690271. [ Links ]

8. Naidoo S. The South African national health insurance: a revolution in health-care delivery. J Public Health (Oxf). 2012 Mar;34(1):149-50. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds008. MID: 22362968. [ Links ]

9. Medical aid coverage of bariatric surgery in South Africa. Available from: http://www.medicalaid-quotes.co.za. [ Links ]

10. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Int Med. 2013;273:219-34. [ Links ]

11. Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741-52. [ Links ]

12. Varban O, Cassidy RB, Bonham A, et al. Factors associated with achieving a body mass index of less than 30 after bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(11):1058-64. [ Links ]

13. Kothari SN, Borgert AJ, Kallies KJ, et al. Long-term (>10-year) outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:972-8. [ Links ]

14. O'Brien PE, MacDonald L, Anderson M, Brennan L, Brown WA. Long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery: fifteen-year follow-up of adjustable gastric banding and a systematic review of the bariatric surgical literature. Ann Surg. 2013 Jan;257(1):87-94. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827b6c02. PMID: 23235396. [ Links ]

15. O'Brien PE, Hindle A, Brennan L, et al. Long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight loss at 10 or more years for all bariatric procedures and a single centre review of 20-year outcomes after adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2019 Jan;29(1):3-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3525-0. PMID: 30293134. [ Links ]

16. Devienne M, Caiazzo R, Chevallier J-M, et al. Comparison of the laparoscopic implantation of an adjustable BIORING® gastric ring versus the VANGUARD®: randomized prospective study. Obésité. 2013 Jun;8(2):63-8. [ Links ]

17. Cousin Adhesix® Bioring® Catalogue. 2012: page 11. Available from: https://www.Cousin-biotech.com. [ Links ]

18. 1998 Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults - the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998 Sep 6;(Suppl 2):S51-209. [ Links ]

19. Centre for Public Health Excellence at NICE (UK); National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (UK). Obesity: the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (UK); 2006 Dec. PMID: 22497033. [ Links ]

20. NIH conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Consensus Development Conference Panel. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Dec 15;115(12):956-61. PMID: 1952493. [ Links ]

21. Van Wissen J, Bakker N, Doodeman HJ, et al. Preoperative methods to reduce liver volume in bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2016 Feb;26(2):251-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1769-5. PMID: 26123526. [ Links ]

22. ASMBS updated position statement on prophylactic measures to reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism in bariatric surgery patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013 Jul-Aug;9(4):493-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2013.03.006.PMID: 23769113. [ Links ]

23. Di Lorenzo N, Furbetta F, Favretti F, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding via pars flaccida versus perigastric positioning: technique, complications, and results in 2,549 patients. Surg Endosc. 2010 Jul;24(7):1519-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0669-y. PMID: 20354885. [ Links ]

24. Kroh M, Brethauer S, Duelley N, et al. Surgeon-performed fluoroscopy conducted simultaneously during all laparoscopic adjustable gastric band adjustments results in significant alterations in clinical decisions. Obes Surg. 2010 Feb;20(2):188-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-009-9972-x. PMID: 19763706. [ Links ]

25. Lechner W, Gadenstätter M, Ciovica R, Kirchmayr W, Schwab G. In vivo band manometry: a new access to band adjustment. Obes Surg. 2005 Nov-Dec;15(10):1432-6. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089205774859399. PMID: 16354523. [ Links ]

26. Dixon AF, Dixon JB, O'Brien PE. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding induces prolonged satiety: a randomized blind crossover study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Feb;90(2):813-9. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1546. PMID: 15585553. [ Links ]

27. Burton PR, Brown WA. The mechanism of weight loss with laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: induction of satiety not restriction. Int J Obes. 2011 Sep;35(Suppl 3):S26-30. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2011.144. PMID: 21912383. [ Links ]

28. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004 Aug;240(2):205-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. PMID: 15273542. [ Links ]

29. Evron JM, Herman WH, McEwen LN. Changes in screening practices for prediabetes and diabetes since the recommendation for Hemoglobin A1c testing. Diabetes Care. 2019 Apr;42(4):576-84. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-1726. PMID: 30728220. [ Links ]

30. Thereaux, J, Lesuffleur T, Czernichow S, et al. Association between bariatric surgery and rates of continuation, discontinuation, or initiation of antidiabetes treatment 6 years later. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(6):526-33. [ Links ]

31. Gagner M. Invited commentary: Toward a national surgical strategy for type 2 diabetes resolution: Can we do better? JAMA Surg. 2018 Jun;153(6):533-4. [ Links ]

32. Angrisani L, Cutolo PP, Formisano G, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year results of a prospective, randomized trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:405-13. [ Links ]

33. Miller K, Pump A, Hell E. Vertical banded gastroplasty versus adjustable gastric banding: prospective long-term follow-up study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:84-90. [ Links ]

34. Stroh C, Hohmann U, Schramm H, et al. Fourteen-year long-term results after gastric banding. J Obes. 2011;2011:1284517. [ Links ]

35. Naef M, Mouton W, Naef U, et al. Graft survival and complications after laparoscopic gastric banding for morbid obesity - lessons learned from a 12-year experience. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1206-14. [ Links ]

36. O'Brien PE, Brennan L, Laurie C, et al. Intensive medical weight loss or laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the treatment of mild to moderate obesity: long-term follow-up of a prospective randomised trial. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1345-53. [ Links ]

37. Himpens J, Cadiere GB, Bazi M, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Arch Surg. 2011;146:802-7. [ Links ]

38. Arapis K, Tammaro P, Parenti LR, et al. Long-term results after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity: 18-year follow-up in a single university unit. Obes Surg. 2017;27:630-40. [ Links ]

39. Favretti F, Segato G, Ashton D, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in 1,791 consecutive obese patients: 12-year results. Obes Surg. 2007;17:168-75. [ Links ]

40. Aarts EO, Dogan K, Koehestanie P, et al. Long-term results after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: a mean fourteen-year follow-up study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:633-40. [ Links ]

41. Victorzon M, Tolonen P. Mean fourteen-year, 100% follow-up of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:753-7. [ Links ]

42. Carandina S, Tabbara M, Galiay L, et al. Long-term outcomes of the laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: weight loss and removal rate. A single center experience on 301 patients with a minimum follow-up of 10 years. Obes Surg. 2017;27:889-95. [ Links ]

43. Toolabi K, Golzarand M, Farid R. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: efficacy and consequences over a 13-year period. Am J Surg. 2016;212:62-8. [ Links ]

44. Trujillo MR, Muller D, Widmer JD, et al. Long-term follow-up of gastric banding 10 years and beyond. Obes Surg. 2016;26:581-7. [ Links ]

45. Kowalewski PK, Olszewski R, Kwiatkowski A, et al. Life with a gastric band. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding-a retrospective study. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1250-3. [ Links ]

46. Vinzens F, Kilchenmann A, Zumstein V, et al. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB): results of a Swiss single-center study of 405 patients with up to 18 years' follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1313-9. [ Links ]

47. Niville E, Dams A, Reremoser S, Verhelst H. A mid-term experience with the Cousin Bioring®- adjustable gastric band. Obes Surg. 2012 Jan;22(1):152-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-011-0427-9. PMID: 21544698. [ Links ]

48. Dixon JB, O'Brien PE, Playfair J, et al. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes. A randomized control trial. JAMA, 2008;299(3):316-23. [ Links ]

49. Dixon JB, Murphy DK, Segel JE, et al. Impact of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding on type 2 diabetes. Obes Rev. 2012 Jan;13(1):57-67. [ Links ]

50. O'Brien PE, Dixon JB, Laurie C, et al. Treatment of mild to moderate obesity with laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding or an intensive medical program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006 May 2;144(9):625-33. PMID: 6670131. [ Links ]

51. Lazzati A, De Antonio M, Paolino L, et al. Natural history of adjustable gastric banding: lifespan and revisional rate: a nationwide study on administrative data on 53,000 patients. Ann Surg. 2017 Mar;265(3):439-45. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001879. PMID: 27433894. [ Links ]

52. Favretti F, Ashton D, Busetto L, et al. The gastric band: first-choice procedure for obesity surgery. World J Surg. 2009 Oct;33(10):2039-48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-009-0091-6. PMID: 19551427. [ Links ]

53. Fielding GA, Ren CJ. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band. Surg Clin North Am. 2005 Feb;85(1):129-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2004.10.004. PMID: 15619534. [ Links ]

54. Varban OA, Cassidy RB, Bonham A, et al. Factors associated with achieving a body mass index of less than 30 after bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017 Nov 1;152(11):1058-64. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2348. PMID: 28746723. [ Links ]

55. Di Lorenzo N, Furbetta F, Favretti F, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding via pars flaccida versus perigastric positioning: technique, complications, and results in 2,549 patients. Surg Endosc. 2010 Jul;24(7):1519-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0669-y. PMID: 20354885. [ Links ]

56. Beitner MM, Ren-Fielding CJ, Kurian MS, et al. Sustained weight loss after gastric banding revision for pouch-related problems. Ann Surg. 2014 Jul;260(1):81-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000327. PMID: 24441823. [ Links ]

57. Giet L, Baker J, Favretti F, et al. Medium and long-term results of gastric banding: outcomes from a large private clinic in UK. BMC Obesity. 2018;5(12):1-7. [ Links ]

58. Szewczyk T, Janczak P, Jezierska N, Juralowicz P. Slippage-a significant problem following gastric banding-a single centre experience. Obes Surg. 2018 Apr;28(4):976-80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-3044-4. PMID: 29197047. [ Links ]

59. Eid I, Birch DW, Sharma AM, et al. Complications associated with adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity: a surgeon's guide. Can J Surg. 2011;54(1):61-6. [ Links ]

60. Abu-Abeid S, Szold A. Laparoscopic management of Lap-Band® erosion. Obes Surg. 2001;11:87-9. [ Links ]

61. Niville E, Dams A, Vlasselaers J. Lap-Band erosion: incidence and treatment. Obes Surg. 2001 Dec;11(6):744-7. PMID: 11775574. [ Links ]

62. Arman GA, Himpens J, Dhaenens J, et al. Long-term (11+ years) outcomes in weight, patient satisfaction, comorbidities, and gastro-esophageal reflux treatment after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1778-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.01.013. PMID: 27178613. [ Links ]

63. Felsenreich DM, Langer FB, Kefurt R, et al. Weight loss, weight regain, and conversions to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1655-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.02.021. PMID: 27317599. [ Links ]

64. Juodeikis Z, Brimas G. Long-term results after sleeve gastrectomy: A systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Apr;13(4):693-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.10.006. PMID: 27876332. [ Links ]

65. Sofianos C, Sofianos C. Outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy at a bariatric unit in South Africa. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2016 Nov 15;12:37-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2016.11.005. PMID: 27895905. [ Links ]

66. Khoraki J, Moraes MG, Neto APF, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Am J Surg. 2018 Jan;215(1):97-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.027. PMID: 28693840. [ Links ]

67. Froylich D, Abramovich-Segal T, Pascal G, et al. Longterm (over 10 years) retrospective follow-up of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2018 Apr;28(4):976-80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-3044-4. PMID:29197047. [ Links ]

68. Nguyen NT, Slone JA, Nguyen XM, Hartman JS, Hoyt DB. A prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for the treatment of morbid obesity: outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg. 2009 Oct;250(4):631-41. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b92480. PMID: 19730234. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Email: grantdewar@iafrica.com