Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Surgery

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5151

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2361

S. Afr. j. surg. vol.55 no.3 Cape Town Set. 2017

GENERAL SURGERY

Does gender impact on female doctors' experiences in the training and practice of surgery? A single centre study

F UmoetokI; J M Van WykII; T E MadibaI

IDepartment of Surgery, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine, College of Health Sciences University of KwaZulu-Natal

IIClinical and Professional Practice, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine, College of Health Sciences University of KwaZulu-Natal

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Surgery has been identified as a male-dominated specialty in South Africa and abroad. This study explored how female registrars perceived the impact of gender on their training and practice of surgery.

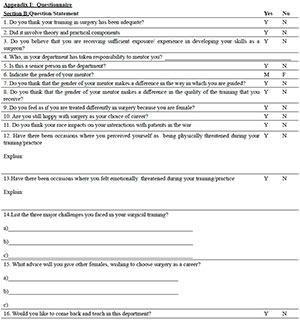

METHOD: A self-administered questionnaire was used to explore whether females perceived any benefits to training in a male-dominated specialty, their choice of mentors and the challenges that they encountered during surgical training.

RESULTS: Thirty-two female registrars participated in the study. The respondents were mainly South African (91%) and enrolled in seven surgical specialties. Twenty-seven (84%) respondents were satisfied with their training and skills development. Twenty-four (75%) respondents had a mentor from the department. Seventeen (53%) respondents perceived having received differential treatment due to their gender and 25 (78.2%) thought that the gender of their mentor did not impact on the quality of the guidance received in surgery. Challenges included physical threats to female respondents from patients and disrespect, emotional threats and defaming statements from male registrars. Additional challenges included time-constraints for family and academic work, poor work-life balance and being treated differently due to their gender. Seventeen (53%) respondents would consider teaching in the Department of Surgery.

CONCLUSION: Generally, females had positive perceptions of their training in Surgery. They expressed concern about finding and maintaining a work-life balance. The gender of their mentor did not impact on the quality of the training but 'bullying' from male peers and selected supervisors occurred. Respondents will continue to recommend the specialty as a satisfying career to young female students.

Introduction

Globally, the entry of female students into medical schools has increased dramatically.1 An escalation in female enrolment has been reported in South Africa over the past two decades.2,3 The consequent increase in the number of women enrolled in the health care sector resulted in the term 'pink collar medicine'.4 This generated discourse around representation according to gender in professional medical and academic organisations. It has also raised questions about how values, ascribed to the different genders will impact on the psychosocial practice and/or business aspects of medicine.5 Debates such as these have given rise to a focus on gender-based discrimination in medicine, and attempts to understand the barriers that affect the integration of women in medicine. The under-representation of women in prestigious, high income specialties and their sluggish progression to leadership on professional bodies and in academic medicine 6,7 have been widely researched.

Medicine in general is dominated by men and the resultant patriarchal culture gives rise to structural, attitudinal and behavioural obstacles.8 Gender discrimination remains widespread and has been reported during selection for surgical residency programmes in the USA.9 Women find it difficult to get selected into managerial positions, even when they are suitably qualified.6,10 To illustrate, a study reported that women surgeons in the USA were just regarded as 'women who completed surgical training' but not truly recognized as surgeons.9

One of the first documented accounts of discrimination against women in medicine dates back as far as the 19th century. The account details the story of Dr James Barry, born as Margaret Ann Bulkley, who became well known as the surgeon who performed the first successful caesarean section in the Republic of South Africa. Bulkley reportedly pretended to be a man in order to practice as a surgeon.11

Most studies of female doctors' experiences and perceptions reported on the experiences of practitioners from developed countries. Very little has been recorded about this phenomenon in the developing country context, thus the need for this study.

Methodology

This mixed-method, exploratory case study was conducted to describe the experiences of female registrars at the Nelson R Mandela School of Medicine of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), Durban, South Africa. The study population was a purposive sample 12 of all female registrars (or residents) in the first to fourth years of training, who were exposed to workplace-based service training at public hospitals in the Durban functional region. These participants, as female doctors, were in the best position to provide details of their perceptions on surgical training at the institution. Of the 33 potential participants who were approached from two training hospitals frequented by the main author, one person declined to complete the questionnaire.

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected by means of a self-administered questionnaire to explore the perceptions of female respondents towards the influence of gender on their experience and clinical practice. Using a self-administered questionnaire,13 respondents' were asked about the quality of their experiences as female registrars during surgical training, the adequacy of practice opportunities, the availability and preferences that they had in relation to mentors and their challenges during training. Participants were also asked about (i) specific challenges encountered during their training, (ii) their perceptions of being treated differently based on their gender, and (iii) their perceptions of the impact of gender on their relationships with their patients and their colleagues. The questions also explored whether gender had influenced the quality of their training in surgery.

Data were collected by the first author at face to face sessions during August-December 2015 and captured in an Excel spreadsheet. The quantitative data were analysed descriptively while the qualitative data from open-ended questions were transcribed verbatim and analysed independently to identify themes.14 All respondents were informed of the purpose of the study and their right to withdraw at any stage. They were however encouraged to complete the questionnaire. Ethical approval and gatekeeper's permissions were obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (BE 004/15).

Results

Demographical details

A total of 32 (69.5%) female registrars were purposively invited to participate from the total number of female registrars (N=46) enrolled in the Surgical disciplines. The median age of the respondents was 36 years (std dev=7.3). The racial breakdown included Black (n=17, 63%); White (n=3, 9%) and Indian females (n=12, 38%). Twenty-nine (91%) respondents were South African citizens and 3 (9%) were foreign nationals. Table 1 illustrates the demographic and specialty profile of the respondents.

Reflection on Training/Mentorship

All respondents (100%) were satisfied with both the theoretical and practical components as well as the quality of their post-graduate training in surgery. Twenty-seven (84%) respondents perceived their practical training to develop their skills as successful surgeons to be sufficient. Twenty-four (75%) respondents indicated having identified a mentor in their department. All these respondents believed that the gender of their mentor did not impact on the quality of their training. Thirteen (41%) respondents had identified a male mentor; eight (25%) had identified a female mentor and 11 (32%) had no mentor. Seven (22%) respondents believed that the gender of their mentor had made a difference in the type and quality of the mentorship that they had received during training.

Challenges, Threats and Discrimination

The reported challenges of the respondents included physical threats from patients to their safety (n=11; 34%) and emotional threats (13; 40%) from peers and supervisors. Sixteen (50%) respondents experienced bullying that included defaming statements being made about them in their absence by male registrars, being disrespected through behaviour and abusive language and being told that surgery was not for females. All respondents perceived training and practice in surgery as time consuming. The time allocations impacted on their responsibility to their families. They felt guilty for trying to balance their service and family commitments. The service commitments also impacted on the time allocated to their academic studies with many complaining of long working hours and difficulty in completing the research component of their post-graduate studies. Other challenges included 'biased' rotations; non-exposure to interesting cases and discrimination due to gender. One respondent reported being 'treated at times like a gender quota'. Another remarked that others were being favoured over her as she is a 'foreigner'.

Reflection on choice of training as a surgeon

Despite feelings of persecution, all the respondents remained adamant that young female students should not be afraid to pursue surgery as a specialty. They believed that female doctors should expect some obstacles during training. They, however, warned that the pursuit of a surgical specialty would impact on females' decisions, such as whether to delay marriage and having children or whether to consider marriage at all. Overall, the respondents were positive that choosing surgery was the right thing to do. Seventeen (53%) respondents indicated an interest in teaching and serving as female role models in the Department of Surgery.

Impact on family life

Qualitative comments suggest that some participants struggled to adjust to the demands of the discipline due to being female. One thought that "women are not taken seriously, as they may soon get pregnant" another mentioned that "surgery will make you delay getting married and starting a family'. In summary, they found it challenging to function both as "a mother and a surgeon."

Discussion

All respondents in our study were satisfied with the quality of the registrar training that they received. Similar observations had been made in the literature. A Canadian study reported on women surgeons' satisfaction with their career, despite noting the compromises involved.15 A study from the USA similarly reported that female doctors were satisfied with their careers in surgery. All the females in that study were, however, unmarried and childless, worked more hours and did more calls than their female counterparts in other disciplines.16

Twenty-two percent of the respondents in our study believed that the gender of their mentors had made an impact on the quality of their training. The absence of female mentors is believed to be a major contributing factor to the persistent male culture and resultant barrier to career advancement of female academics in surgery.17 In a Canadian study, Seemann et al6 similarly reported that 89% of the respondents had identified a male mentor but that 54% had wished for better mentorship.

Eleven respondents in our study reported having no formal mentoring. A study in the USA similarly reported an absence of mentors for 50% of the women surgeons. A study of female paediatric surgeons in the USA concluded that female role models were necessary to recruit more female doctors into surgical specialties.18 The participants of that study, however, ascribed their continued commitment to surgery to having excelled in attributes such as perseverance, drive and having a positive outlook.19 These observations support our findings in this study where women stated their commitment to surgery despite the highlighted challenges.

Women leaders in surgery reported discrimination as occurring throughout their careers including medical school, in residency, fellowship and as staff surgeons.6 Fifty-six percent of the respondents in that study also cited gender as the most common source of discrimination, and less commonly cited were age, race and culture.6 Likewise, in the present series, female doctors reported many challenges which ranged from physical and emotional threats to disrespect, bullying and discrimination. Of additional interest was the fact that respondents were willing to encourage female medical students to pursue careers in surgery but highlighted the need to anticipate challenges.

All respondents thought that they had made sacrifices to their family life in order to continue their commitment to the discipline. Female doctors have a need to balance their career and family life. This has been done successfully by women surgeons in Canada despite the reports that it involved a number of compromises.15 The compromises included decisions about having children when working in institutions that lacked maternity policies, with 23% reporting inadequate time for breastfeeding, 74% breastfeeding for fewer than 4 months, 61% returning to work while still breastfeeding and 55% resorting to live-in child care.15 In a comparative study of female surgeons in Japan, USA and Hong Kong, Kawase et al. pointed to the added pressure imposed by culture on women's roles in their families.20 There is still much to do before genuine 'feminist' transformation becomes a reality in the discipline. Men still outnumber women in key positions in the medical profession, surgery is not an exception. Institutional, social and cultural factors collude to discriminate against women in medicine.

Limitations

This exploratory case was conducted at a single institution in KwaZulu-Natal. Respondents were all registrars, represented 7 subspecialties and various racial and cultural groups. The views of the females in this study cannot be generalised to other institutions, but it is recommended that researchers compare the context of this setting to their own to benefit from the lessons.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that gender has an impact on female doctors' experiences in the training and practice of surgery. Despite challenges, all respondents remained adamant that young female students should not be afraid to pursue their study of surgery. They believed that female doctors should expect some obstacles during training. Respondents warned that choosing to specialise in surgery would ultimately impact on decisions regarding personal choices, such as whether to get married or delay marriage and whether/not to have children. The problem of male domination and discrimination against women in surgery can be addressed by an increased awareness of the phenomenon. It is also recommended that departments review the working hours to ensure some degree of balance for surgeons and their families.

REFERENCES

1. Riska E. Women in the Medical Profession: International Trends. In: Kuhlmann E, Annandale E, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Gender and Healthcare. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2010. p. 389-404. [ Links ]

2. Breier M, Wildschut A. Changing gender profile of medical schools in South Africa. SAMJ [Online]. 2008 (Accessed on 23 Sep 2016);98(7):557-60. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18785399. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18785399 [ Links ]

3. De Vries E, Irlam J, Couper I, Kornik S. Career plans of final-year medical students in South Africa. SAMJ [Online]. 2010 (Accessed on 23 Sep 2016);100(4):227-8. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0256-95742010000400021&lng=en [ Links ]

4. Heru AM. Pink-collar medicine: Women and the future of medicine. Gender Issues [Online]. 2005 (Accessed on 3 Oct 2016);22(1):20-34. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12147-005-0008-0 [ Links ]

5. Sen G, Ostlin P, George A. Unequal unfair ineffective and inefficient. Gender inequity in health: Why it exists and how we can change it. Final report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health2007 (Accessed on 23 Sep 2016). Available from: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/wgekn_final_report_07.pdf [ Links ]

6. Seemann NM, Webster F, Holden HA, Carol-anne EM, Baxter N, Desjardins C, et al. Women in academic surgery: Why is the playing field still not level? Am J Surg [Online]. 2016 (Accessed on 23 Sep 2016);211(2):343-9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.036 [ Links ]

7. Conrad P, Carr P, Knight S, Renfrew MR, Dunn MB, Pololi L. Hierarchy as a barrier to advancement for women in academic medicine. J Womens Health [Online]. 2010 (Accessed on 23 Sep 2016);19(4):799-805. doi: 101080/jwh2009.159 [ Links ]

8. Kane-Berman J, Hickman R. Women doctors in medical professional organisations in South Africa-a report by the Women in Medicine Workgroup. SAMJ [Online]. 2003 (Accessed on 23 Sep 2016);93(1). Available from: www.ajol.info/index.php/samj/article/download/13515/128058 [ Links ]

9. Straehley CJ, Longo P. Family issues affecting women in medicine, particularly women surgeons. Am J Surg [Online]. 2006 (Accessed on 23 Sep 2016);192(5):695-8. doi: 10.1016/j. amjsurg.2006.04.005 [ Links ]

10. Debas HT, Bass BL, Brennan MF, Flynn TC, Folse JR, Freischlag JA, et al. American surgical association blue ribbon committee report on surgical education: 2004. Ann Surg [Online]. 2005 (Accessed on 23 Sep 2016);241(1):1-8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000150066.83563.52 [ Links ]

11. Du Preez HM. Dr James Barry: the early years revealed. SAMJ [Online]. 2008 (Accessed on 23 Sep 2017);98(1):52-8. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0256-95742008000100025&lng=en [ Links ]

12. Tongco MDC. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobotany: Research and Applications [Online]. 2007 (Accessed on 23 Sep 2017);5:147-58. Available from: http://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/34833273/I1547-3465-05-147.pdf [ Links ]

13. Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research methods in Education. London: Routledge Falmer; 2000. [ Links ]

14. Bailey J. First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing 2008 (Accessed on 2016 23.09). Available from: http://fampra.oxfordjournals.org/content/25/2/127.full.pdf+html [ Links ]

15. Mizgala CL, Mackinnon SE, Walters BC, Ferris LE, McNeill IY, Knighton T. Women surgeons. Results of the Canadian Population Study. Ann Surg [Online]. 1993;218(1):37. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1242898/pdf/annsurg00065-0057.pdf [ Links ]

16. Frank E, Brownstein M, Ephgrave K, Neumayer L. Characteristics of women surgeons in the United States. Am J Surg [Online]. 1998;176(3):244-50. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002961098001524 [ Links ]

17. Zhuge Y, Kaufman J, Simeone DM, Chen H, Velazquez OC. Is there still a glass ceiling for women in academic surgery? 2011 (Accessed on 9 Sep 2016):637-43. [ Links ]

18. Caniano DA, Sonnino RE, Paolo AM. Keys to career satisfaction: insights from a survey of women pediatric surgeons. J Pediatr Surg [Online]. 2004;39(6):984-90. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Roberta_Sonnino2/publication/8522331 [ Links ]

19. Kass RB, Souba WW, Thorndyke LE. Challenges confronting female surgical leaders: overcoming the barriers. J Surg Res [Online]. 2006;132(2):179-87. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2006.02.009 [ Links ]

20. Kawase K, Kwong A, Yorozuya K, Tomizawa Y, Numann PJ, Sanfey H. The attitude and perceptions of work-life balance: a comparison among women surgeons in Japan, USA, and Hong Kong China. World J Surg [Online]. 2013;37(1):2-11. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00268-012-1784-9/fulltext.html [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr Jacqueline M van Wyk

vanwykj2@ukzn.ac.za