Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Surgery

On-line version ISSN 2078-5151

Print version ISSN 0038-2361

S. Afr. j. surg. vol.54 n.1 Cape Town Mar. 2016

PAEDIATRIC SURGERY

Gastroschisis in a developing country: Poor resuscitation is a more significant predictor of mortality than postnatal transfer time

P StevensI; E MullerI; P BeckerII

IDepartment of Paediatric Surgery, Steve Biko Academic Hospital, University of Pretoria

IISouth African Medical Research Council

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The time from birth to the first paediatric surgical consultation of neonates with gastroschisis is a predictor of mortality in developing countries. This is contrary to findings in the developed world. We set out to document this relationship within our population.

METHODS: Neonates with gastroschisis who were transferred to Steve Biko Academic Hospital within the study period were included. The association between mortality and demographic, clinical and biochemical variables was assessed. Significant variables after univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate regression.

RESULTS: Sixty patients were included. The mortality rate was 65%. Mean transfer time and distance were 14.9 hours and 225km. Forty-eight per cent of the neonates were either clinically dehydrated or in hypovolaemic shock on arrival. It was shown through univariate analysis that female sex, appropriate weight for gestational age, hydration status, gestation, transfer time, serum urea, base deficit and serum bicarbonate (HCO3) were significant predictors of mortality. Only female sex, appropriate weight for gestational age and serum HC03 were shown to be significant using multivariate analysis.

CONCLUSION: Our high mortality rate was not due to lengthy transfer times. The poor clinical condition of the patients on arrival at our hospital, which relates to deficiencies in the neonatal transfer system, had a direct impact on the survival of neonates with gastroschisis.

Gastroschisis is the most common congenital anterior abdominal wall defect treated in our hospital. Currently the incidence is 2 to 4.9 per 10 000 live births and increasing throughout the world,1,2 with a similar increase reflected in South Africa.3

Mortality of babies born with gastroschisis in developed countries is less than 10%,4 whereas mortality in developing countries is between 35 - 80%.3,5-8

One factor which has been shown to result in increased mortality in developing nations is the delay in transfer of these neonates from peripheral hospitals to specialized institutions.6,7 However multiple studies in first world countries have shown that the absence of prenatal diagnosis and consequent postnatal transfer does not influence morbidity and mortality.9-12 Routine antenatal ultrasound examination is uncommon in the South African public health system and not part of the antenatal workup of uncomplicated pregnancies in all provinces. As a result, the norm is postnatal transfer of neonates diagnosed with gastroschisis at birth to institutions where specialized paediatric surgical care is available.

Mortality of gastroschisis at our institution was previously shown to be at least 38.7%.3

It was not known whether the mortality of neonates born with gastroschisis within our population catchment area could, similarly to other developing countries, be explained by a delay in transfer or not.

This study of neonates born with gastroschisis within our population catchment area set out to document the relation between the time from their birth to admission in our paediatric surgical unit, their clinical condition on arrival and their mortality.

Method

Setting

Steve Biko Academic Hospital is a public tertiary referral hospital in Tshwane (Pretoria) South Africa, attached to the University of Pretoria medical campus. The department of paediatric surgery is 1 of 2 paediatric surgical referral centres for the City of Tshwane, and the only referral centre for the adjacent Mpumalanga province. The paediatric surgical department serves a population of approximately 7 million people,13 with an average of approximately 124 000 births per year.14 Six intensive care unit (ICU) beds and five neonatal ward beds, are available for the treatment of all neonatal surgical admissions.

Study Design

This study was conducted prospectively from February 2011 until September 2013.

All neonates born with gastroschisis and transferred to Steve Biko Academic Hospital during this period were eligible for inclusion in the study. Neonates born with gastroschisis at Steve Biko hospital (inborn) were not eligible for inclusion. The study was undertaken with the approval of the University of Pretoria's MMed and Ethics committees and was therefore performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all babies included in the study.

Data Collection

Data was collected by the admitting doctor in the paediatric surgical department at the initial admission. Data on demographics, birth history, transfer time and transfer distance were collected. Clinically relevant dates and times of birth and admission were recorded. The clinical condition of the child on arrival, as well as the method of bowel coverage by the referring doctor was also recorded. If any birth information was not available, the transferring hospital was contacted to supply missing information from their birth registers. On admission blood was also taken for analysis of the patient's metabolic status in the form of an arterial blood gas, serum urea (sUrea) and serum creatinine (sCreat). Upon outcome, dates of discharge or mortality were recorded. Data was collected according to definitions in Table 1.

Outcomes

The primary outcome studied was survival to hospital discharge or in hospital mortality.

Statistical Analysis

To determine risk factors for mortality the modelling approach was to consider the associations between mortality and the individual demographic, clinical and biochemical variables. Univariate analysis was done using Fisher's exact test for categorical data and Welch's t-test for continuous data. Those factors that were significant at a liberal p value of 0.15 were included in a multivariate regression model. A stepwise model was then used to determine the significant factors retained in the final model (p<0.05).

Results

Sixty two patients with gastroschisis were admitted from referring hospitals during the study period. Two patients were excluded from the study. One patient was excluded because the admission data was not recorded adequately and 1 patient was excluded as the patient received specialist paediatric surgical care prior to transfer to our department. During the study period four inborn patients were ineligible for the study. Sixty patients were subjected to statistical analysis.

The mortality rate for the cohort was 65%. Univariate analysis of the categorical variables is shown in Table 2, and of the continuous variables in Table 3.

A male to female ratio of 2:3 was evident. Mean birth weight was 2.4kg and gestation was 36 weeks. Most neonates were born below 2.5kg (65%), while there were similar numbers of small for gestational age and appropriate for gestational age neonates. The mean maternal age was 21 years. The minority of births occurred outside a healthcare facility (17%).

Mean transfer time was 14.9 hours (Median 9hrs, Range 3.3-106.4hrs.) and transfer distance was 225km (19-439km).

The hydration status of 48% of neonates was assessed as either dehydrated or in hypovolemic shock. Only 1 patient arrived without any coverage of the viscera, while 68% of neonates had their exposed viscera covered with a modified intravenous fluid bag. Eight patients arrived with a temperature of less than 36°C, five of whom had a temperature of less than or equal to 35°C. The majority of neonates were admitted to the paediatric surgical ward (68%) and not ICU. Two patients had complete midgut necrosis on admission, were not actively managed further and were transferred back to the referring hospitals for palliative care after counselling the parents. Both were included in the mortality group.

The mean blood gas analysed serum bicarbonate (sHCO3) for those that survived was 16.67mmol/l while the mean sHC03 on admission of neonates who died was 14.61mmol/l, pH was 7.32 and pC02 was 26.74mmHg.

Univariate analysis revealed that variables associated with mortality at a liberal p value of 0.15 included: female sex, appropriate weight for gestational age, hydration status of dehydrated or in hypovolemic shock, gestation, transfer time, sUrea, arterial base deficit and arterial serum bicarbonate (sHCO3).

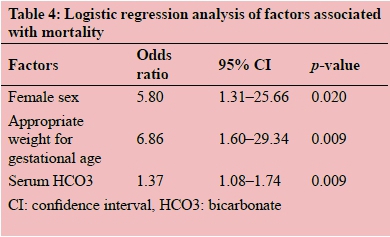

Logistic regression analysis (Table 4) found only female sex, appropriate weight for gestational age and sHC03 on admission to be significantly associated with mortality (p<0.05). The odds of mortality in a female neonate with gastroschisis were 5.8 times that of a male neonate (p=0.02). Neonates with gastroschisis and appropriate weight for gestational age had a 6.8 fold greater odds of mortality during their admission than those who were small for gestational age (p=0.009). A decrease of 1 mmol/l in sHCO3 measured on admission, resulted in a 1.37 fold increase in odds of mortality (p=0.009).

Discussion

The mortality rate for this study of 65% was far greater than our previously reported mortality of 38.7% for neonates with gastroschisis.3 The previous study's inclusion of inborn patients from both Steve Biko and Kalafong hospitals, as well as a 16 month deficiency in their data collection would have influenced this comparison. This is however unlikely to explain the large difference in mortalities between studies. Of note in our current study was that gastroschisis was the underlying cause of death in 33% of all mortalities in our unit over the study period.

The previous study identified 48 cases of gastroschisis over a 20 year period (1981-2001),3 whereas our 60 patients were admitted over a 32 month period. This is in keeping with the rise in the incidence of gastroschisis worldwide,2 as well as reflecting the likely increase in the population within our drainage area. Our cohort is far greater than the 19 neonates with gastroschisis reported over a 4 year period in Cape Town,1 and similar to the cohort of approximately 17 patients per year reported in Durban.17 Further epidemiological studies are required to accurately assess the incidence of this disease across the South African paediatric surgical centres.

A mean maternal age of 21 years is in keeping with reported data of a higher incidence of gastroschisis amongst babies of young mothers.18

Lower gestational age did not result in greater odds of mortality in our study despite the mean gestation being preterm, 36 weeks. Spontaneous preterm labour is more common in pregnancies complicated by foetal gastroschisis,19 and our results are in keeping with these findings.

The finding that small for gestational age neonates in our cohort had a lower odds of mortality than their appropriate for gestational age counterparts is counter intuitive. It is accepted that small for gestational age neonates have a greater mortality when compared to those with appropriate weight, especially in the preterm neonate.20 With a mean gestation of 36 weeks for our cohort, it is difficult to explain the significant difference in mortality (48.3% vs. 80.7%), between the small- and appropriate for gestational age groups, that remains consistent after multivariate analysis. Controlling for prematurity also does not change the findings as equal numbers of small- and appropriate for gestational age births were preterm.

It is our policy to admit all neonates with gastroschisis to the ICU facility if a bed is available. As only 32% of the cohort was admitted initially to ICU, it is evident that we, as with most developing countries, have significant difficulty in caring for these patients in an appropriate ICU setting due to lack of available facilities.

The type of material used to cover the viscera by the transferring medical practitioner was not shown to influence mortality. Two patients who had their exposed viscera directly covered with gauze arrived with acute haemorrhage from their livers due to erosion by the dried out gauze, neither survived. We therefore advocate the use of a soft plastic covering of the viscera, in keeping with published guidelines.9,21 Female sex resulted in significantly greater odds of mortality in our cohort. This contradicts previous results that indicated a higher risk of mortality in males.22

Our chief aim was to evaluate if transfer time was a significant predictor of mortality amongst neonates born with gastroschisis in our drainage population. We showed, that contrary to previous studies in developing countries,6,7 transfer time itself does not seem to be a predictor of mortality. We, however, need to factor in the role a prolonged transfer time plays in the on-going dehydration of these neonates and its influence on their sHCO3, which was shown to be a significantly associated with mortality. The metabolic findings on admission indicated a state of compensated metabolic acidosis in those neonates who eventually died, likely resulting from fluid and heat losses that these neonates experience if not appropriately managed. None of the clinical variables withstood logistic regression as significant. Mills et al showed that clinical variables in the form of the score for neonatal acute physiology-II (SNAP-II) to be a significant predictor of mortality and survival outcomes in gastroschisis.23 Review of our data and inclusion of a SNAP-II on admission would have allowed us to compare our cohort with this study directly. Using the SNAP-II would have allowed us to gain a structured overall clinical impression for comparison, rather than using individual clinical factors. Unfortunately the data required for completing the SNAP-II was not completely recorded to allow its utilization in retrospect.

Despite advice to referring doctors it is not uncommon for patients to arrive from the transferring hospital without a functional intravenous line, a finding similar to Hadley and Mars.24 While we can only speculate as to whether these were functioning prior to transfer or not, the management of the neonates prior to, and during transfer is brought into question by their poor clinical state on arrival. Poor neonatal transfer systems in South Africa have been shown to contribute to poorer outcomes.24,25 Transfer times and poor clinical state of the patients on arrival at our hospital is further testament to the deficiencies in neonatal transfer within our healthcare system.

It must be noted that some patients were not able to be transferred timeously due to the lack of available beds in our hospital. These patients were diverted to other paediatric surgical centres or were transferred to the nearest hospital with the highest available level of care while awaiting a bed in our unit. Reasons for the lengthy transfer time and poor condition of the child on arrival were not included in this study, opportunity therefore exists for further research to accurately identify these causes and aid in addressing the high mortality of gastroschisis in our unit, and elsewhere in South Africa.17 Likely areas of concern include: delay in initial consultation from the peripheral hospital, delay in ambulance transport to collect the patient, inadequate initial resuscitation prior to transport, failure of the referring doctor to adhere to telephonically communicated management as well as equipment and medication shortages at the peripheral hospitals and during ambulance transport.

We did not include the influence of varying methods of definitive surgical treatment of gastroschisis on the outcomes.

Due to the long transfer times and poor clinical condition of our cohort on arrival, the majority of patients were initially stabilised with application of a preformed silo bag, with delayed closure of the abdomen. Some patients however were closed primarily. This decision was made by the treating surgeon based on the appearance of the bowel, the clinical condition of the patient and the availability of a postoperative ICU bed. The relationship of treatment method and outcome at our institution therefore remains to be studied, but the cohort would have to be far larger to show any significant difference in outcomes as very few patients are closed primarily. As the state of the bowel and condition of the patient at initial presentation determine the method of surgical treatment employed, findings of the relationship between treatment used and outcomes would not be independent of the clinical condition of the patient on arrival in our unit.

In conclusion, while we have shown that our high mortality rate does not seem to be directly due to lengthy transfer times, the poor clinical condition of the patients on arrival at our hospital, likely related to the deficiencies in our neonatal referral and transfer system, has a direct impact on the survival of neonates with gastroschisis. If these patients are adequately resuscitated prior to, and during transfer, we may see a decline in the high mortality rate of gastroschisis within our population.

REFERENCES

1. Baerg J, Kaban G, Tonita J et al. Gastroschisis: A Sixteen-Year Review. J Pediatr Surg 2003;38(5):771-774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/jpsu.2003.50164 PMID: 12720191 [ Links ]

2. Suita S, Okamatsu T, Yamamoto T et al. Changing Profile of Abdominal Wall Defects in Japan: Results of a National Survey. J Pediatr Surg 2000;35(1):66-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3468(00)80016-0 PMID: 10646777 [ Links ]

3. Arnold M. Is the incidence if gastroschisis rising in South Africa in accordance with international trends? S Afr J Surg 2004;42(3):86-88 PMID: 15532615 [ Links ]

4. Driver CP, Bruce J, Bianchi A et al. The Contemporary Outcome of Gastroschisis. J Pediatr Surg 2000;35(12):1719-1723. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jpsu.2000.19221 PMID: 1101722 [ Links ]

5. Ameh EA, Chirdan LB. Ruptured exomphalos and gastroschisis: a retrospective analysis of morbidity and mortality in Nigerian children. Pediatr Surg Int 2000;16:23-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s003830050006 PMID: 10663828 [ Links ]

6. Harrison DS, Mbuwayesango BE. Factors Associated with Mortality among neonates presenting with gastroschisis in Zimbabwe (Abstract). S Afr J Surg 2006;44(4):157 [ Links ]

7. Vilela PC, Ramos de Amorim MM, Falbo GH et al. Risk Factors for Adverse Outcome of Newborns with Gastroschisis in a Brazilian Hospital. J Pediatr Surg 2001;36(4):559-564. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jpsu.2001.22282 PMID: 11283877 [ Links ]

8. Askarpour S, Ostadian N, Javaherizadeh H et al. Omphalocele, Gastroschisis: Epidemiology, Survival and Mortality in Imam Khomeini Hospital, Ahvaz- Iran. Pol Przegl Chir 2012;84(2):82-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/v10035-012-0013-4 PMID: 22487740 [ Links ]

9. Stoodley N, Sharma A, Noblett H et al. Influence of place of delivery on outcome in gastroschisis. Arch Dis Child 1993;68:321-323. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/adc.68.3_spec_no.321 PMID: 8466271 [ Links ]

10. Nicholls G, Upadhaya V, Gornall P et al. Is specialist centre delivery of gastroschisis beneficial? Arch Dis Child 1993;69:71-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/adc.69.1_spec_no.71 PMID: 8346959 [ Links ]

11. Singh SJ, Fraser A, Leditschke JF et al. Gastroschisis: determinants of neonatal outcome. Pediatr Surg Int 2003;19:260-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00383-002-0886-0 PMID: 12682747 [ Links ]

12. Bucher BT, Mazotas IG, Warner BW et al. Effect of time to surgical evaluation on the outcomes of infants with gastroschisis. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:1105-1110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.03.016 PMID: 22703778 [ Links ]

13. Statistics South Africa, Census 2011. http://beta2.statssa.gov.za/ (accessed 2 December 2013) [ Links ]

14. Statistical release P0305, Recorded Live Births 2012. Statistics South Africa. http//www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0305/P03052012.pdf (accessed 2 December 2013) [ Links ]

15. Battaglia FC, Lubchenco LO. A practical classification of newborn infants by weight and gestational age. J Pediatr 1967;71(2):159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(67)80066-0 PMID: 6029463 [ Links ]

16. Ade-Ajayi N, Ameh E, Canvassar N et al. Gastroschisis: A multi-centre comparison of management and outcome. Afr J Paediatr Surg 2012;9(1):17-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0189-6725.93296 PMID: 22382099 [ Links ]

17. Sekabira J, Hadley GP. Gastroschisis: a third world perspective. Pediatr Surg Int 2009;25:327-329. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00383-009-2348-4 PMID: 19288118 [ Links ]

18. Frolov P, Alali J, Klein MD. Clinical risk factors for gastroschisis and omphalocele in humans: a review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int 2010;26:1135-1148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00383-010-2701-7 PMID: 20809116 [ Links ]

19. Barseghyan K, Aghajanian P, Miller DA. The prevalence of preterm births in pregnancies complicated by gastroschisis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012;286(4):889-992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2394-3 PMID: 22660889 [ Links ]

20. Katz J, Lee ACC, Lawn JE et al. Mortality risk in preterm and small-for-gestational-age infants in low-income and middle-income countries: a pooled country analysis. Lancet 2013;382:417-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60993-9 PMID: 23746775 [ Links ]

21. Stringer MD, Brereton RJ, Wright VM. Controversies in the management of gastroschisis: a study of 40 patients. Arch Dis Child 1991;66:34-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/adc.66.1_spec_no.34 PMID: 1825461 [ Links ]

22. Clark RH, Walker MW, Gauderer MW. Factors associated with mortality in neonates with gastroschisis. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2011;21(1):21-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1262791 PMID: 21328190 [ Links ]

23. Mills JA, Lin Y, MacNab YC et al. Perinatal predictors of outcome in gastroschisis. J Perinatol 2010;30:809-813. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/jp.2010.43 PMID: 20357809 [ Links ]

24. Hadley GP, Mars M. Improving neonatal transport in the Third World - technology or teaching. S Afr J Surg 2001;39(4):122-124 PMID: 11820142 [ Links ]

25. Lloyd LG, de Witt TW. Neonatal mortality in South Africa: How are we doing and can we do better? S Afr Med J 2013;103(8):518-519. http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.7200 PMID: 23885729 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Paul Stevens

drpsstevens@gmail.com