Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Surgery

On-line version ISSN 2078-5151

Print version ISSN 0038-2361

S. Afr. j. surg. vol.53 n.3-4 Cape Town Dec. 2015

GENERAL SURGERY

International medical graduates in South Africa and the implications of addressing the current surgical workforce shortage

V Y Kong; J J Odendaal; B Sartorius; D L Clarke

Pietermaritzburg Metropolitan Trauma Service, Department of Surgery, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The surgical workforce in South Africa is currently insufficient in being able to meet the burden of surgical disease in the country. International medical graduates (IMGs) help to alleviate the deficit, yet very little is known about these doctors and their career progression in our healthcare system.

METHOD: The demographic profile and career progression of IMGs who worked in our surgical department in a major university hospital in South Africa was reviewed over a four-year period.

RESULTS: Twenty-eight IMGs were identified. There were 23 males (92%) and their mean age was 33 years. Seventy-one per cent (20/28) were on a fixed-term service contract, and returned to their respective country of origin. The option of renewing their service contracts was available to the 16 IMGs who left. Three explicitly indicated they would have stayed in South Africa if formal training was possible. Eight of the 28 IMGs (29%) extended their tenure, and remained in the service position as medical officers. All of the eight IMGs stayed with the intention of entering a formal surgical training programme.

CONCLUSION: IMGs represented a significant proportion of service provision in our unit. Over one third of IMGs stayed beyond their initial tenure, and of these, all stayed in order to gain entry into the formal surgical training programme. A significant proportion of those who left would have stayed if entry to the programme was feasible.

The ample clinical caseload, coupled with a well-established training system, makes South Africa a popular destination for international medical graduates (IMGs) looking to further their surgical training.1,2 There is an endemic shortage of medical doctors in the country, and this deficit is especially pronounced in the rural areas.3-5 IMGs have helped to alleviate this deficit, while a considerable proportion of surgical services at public hospitals across the country are currently delivered by IMGs.6 Although some IMGs wish to stay on in the hope of entering the general surgery registrar programme to become specialists, government legislation continues to restrict the ability of IMGs to practise freely in South Africa.6,7 Most IMGs are restricted to working in underserved rural areas, and cannot easily enter the general surgery registrar programme based in university hospitals.6,7 A paucity of literature focuses specifically on the career paths of IMGs currently serving in the South African healthcare system. The objective of this study was to review the demographic profiles and career intentions of IMGs currently working in a university hospital, in the hope of providing insight into the contribution that this group of doctors makes to surgical services in the South African healthcare system.

Method

Setting

This was a retrospective study, conducted at the Pietermaritzburg Metropolitan Hospitals Complex in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained departmental database was conducted over a four-year period from January 2010 to December 2013. Ethics approval for this study, and to maintain this registry, was granted by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (Ethics Reference No BE 207/09).

Surgical training

The Department of Surgery is an academic department under the auspices of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, and is responsible for postgraduate training in general surgery, accredited by the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA), the national regulatory authority for medical licensing. The general surgery registrar programme lasts for a total of four years. Upon successful completion of the training programme and the examination process, the individual is awarded with Fellowship of the College of Surgeons of South Africa [FCS(SA)], and is eligible to practise independently as a specialist in general surgery.

A non-specialist doctor who works in the Department of Surgery may or may not be in a designated training programme. A registrar is a doctor who is in the general surgery registrar programme, while a medical officer is not.

An IMG in this study was defined as a medical doctor whose primary medical qualifications were obtained from a country outside of South Africa, and who did not have permanent residency. A local medical graduate (LMG) was defined as a medical doctor who obtained his or her primary qualification in South Africa, and had permanent residency therein. LMGs can apply directly to the general surgery registrar programme, subject to the selection requirement of individual training programme. However, to enter the general surgery registrar programme, an IMG is required to pass the HPCSA board examination and must be granted a license to practise, and this is restricted to public hospitals. The IMG must then obtain permanent South African residency. To be eligible for this, the individual must have been resident in the country for five years or longer. The IMG is usually required to re-sit the local medical school final MBChB examination as currently an overseas primary medical qualification is not considered to be compatible with the local qualification. If the IMG is eligible to join the general surgery registrar programme, the entire four-year programme must be completed as retrospective recognition of experience is not commonly accepted.

The study

A review was conducted on IMGs working in the Pietermaritzburg Metropolitan Hospitals Complex during the four-year study period, but not in the general surgery registrar programme at the time of the study. All of the IMGs were personally known to the authors. As an accredited training unit, formal appraisals are conducted routinely at regular intervals. Typically, this occurs every three months and deliberately coincides with a change in doctors for each surgical firm on a rotational basis. This serves as a guide to facilitate the assignment of IMGs to clinical rotation, congruent to their career intentions. The rotation is conducted by the academic director of the department, who is also responsible for monitoring the progress of IMGs. The information was entered into the departmental database. Only IMGs on whom complete data were available were included. Basic demographic information were extracted onto a Microsoft® Excel® spreadsheet for processing, including age, gender and the graduating medical school. The country of origin and primary medical qualification of each IMG was also reviewed.

Results

Basic demographic information

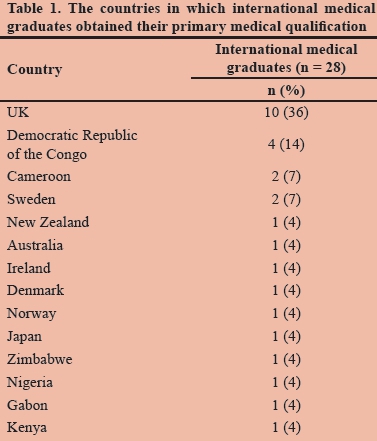

Sixty-seven non-specialist doctors were identified during the four-year study period. There were 31 registrars, all of whom were LMGs. There were 36 medical officers, of whom 28 were IMGs and eight LMGs. A total of 28 IMGs had worked, or were currently working, in the Pietermaritzburg Metropolitan Hospitals Complex. There were 23 (92%) males and 5 (18%) females, with a mean age of 33 years. The countries where IMGs obtained their primary medical qualification are summarised in Table 1.

Career progression

Of the 28 IMGs who joined the department, 71% (20/28) were on a fixed-term service contract, and returned to their respective country of origin. Four of the 20 IMGs who left were on an exchange trauma fellowship programme, sponsored by their home country (two from Cameroon, one from Kenya and one from Gabon). The remaining 16 IMGs who left had the option of extending their tenure, as they were on a salaried medical officer contract, which was renewable. Of the 16 IMGs who left, all of them returned to their country of origin in order to complete their surgical training. Three specifically indicated that they would have stayed in South Africa if entry to the general surgery registrar programme was possible.

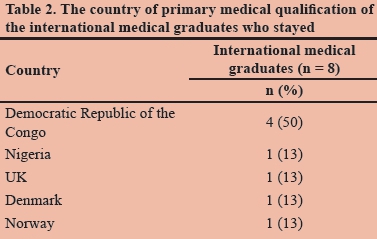

Eight of the 28 IMGs (29%) extended their tenure, and remained in the service position. All eight IMGs stayed with the intention of entering the general surgery registrar programme. The four IMGs, all from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, had no intention of returning to their own country, and would consider staying on in a permanent service role if entry to the general surgery registrar programme was unsuccessful. The remaining four IMGs, one from Nigeria, one from the UK, one from Denmark and one from Norway, intended to eventually return to their own country if entry to the general surgery registrar programme was unsuccessful.

The country of primary medical qualification of the IMGs who stayed is summarised in Table 2.

Discussion

South Africa has a well established surgical training system based on the British training model, and is highly regarded worldwide.1,2 Although approximately 25 surgeons per year currently graduate from the eight medical schools, it is estimated that at least 50 surgeons per year need to graduate in order for adequate access to surgical care to be provided to the entire population.4 The public sector currently provides care to over 80% of the population.4,5 Mass migrations of South African doctors, particularly to developed countries and through entry into private practice, have often been regarded as key factors that are perpetuating this shortage.4,5,8 The problem of a declining surgical workforce is not unique to South Africa, and is a concern throughout the world.9

The uniqueness of South Africa's surgical experience lies in the high volume of a wide spectrum of surgical pathologies which are infrequently encountered in the developed world.1,2,10,11 The trauma experience in South Africa is also unique and is well regarded worldwide.12,13 This unparalleled surgical exposure, together with the country's lifestyle, comparable to that of developed countries for professionals, often attracts IMGs to work in South Africa. However, little is known on the profiles and eventual career progression of these IMGs. It is known that MGs are primarily employed in service roles to bridge the gap created by the medical staffing shortage in the public sector. However, their formal career pathway has not been studied and is not well established. This contrasts with the situation in the USA where IMGs represent a significant proportion of graduates in residency programmes.14 We believe that this may well be attributed to the current government legislation which restricts training for IMGs in South Africa.

Our current data show that approximately one third of all IMGs in our unit stayed beyond their initial fixed-term tenure. All of them intended to stay and enter the general surgery registrar programme. Of those who left, a significant proportion would have stayed if entry to the general surgery registrar programme had been possible. It would appear that many IMGs may well have initially come to South Africa with the intention of returning home, but then decided to stay. Those who wish to stay in South Africa will inevitably continue to provide service to the public sector. They represent a vital resource which helps to ameliorate the current medical staffing shortage. A significant proportion of IMGs attempting to enter the general surgery registrar programme at the time of the study did not wish to continue their career as non-specialist service doctors, and thus chose to return to their own country in order to specialise. This is consistent with a recent study from the UK in which it was demonstrated that over 70% of trainees in general surgery would not accept a career as a subconsultant in a permanent service role.15 Critics have argued that limited training resources should be reserved for LMGs as IMGs have the option of leaving the country after their training. Currently, there is no evidence that IMGs who are permitted to train in South Africa leave following the completion of their training. Providing otherwise well-motivated IMGs access to the current healthcare system could be a solution with which to address the medical staffing shortage in the country.

Conclusion

Over one third of IMGs in our unit stayed beyond their initial tenure, and of this one third, all stayed in order to gain entry to the general surgery registrar programme. A significant proportion of those who left would have stayed if entry to the general surgery registrar programme had been feasible. It is recommended that the current government restriction of IMG access to the general surgery registrar programme should be reviewed in view of the current surgical workforce shortage.

REFERENCES

For a full list of references, please see the online version.

1. Bornman PC, Krige JE, Terblanche J, et al. Surgery in South Africa. Arch Surg. 1996;131(1):6-12. [ Links ]

2. Degiannis E, Oettle GJ, Smith MD, et al. Surgical education in South Africa. World J Surg. 2009;33(2):170-173. [ Links ]

3. Clarke DL. Ensuring equitable access to high quality care: the task of uplifting trauma care in rural and district hospitals. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(9):588. [ Links ]

4. Kahn D, Pillay S, Veller MG, et al. General surgery in crisis: the critical shortage. S Afr J Surg. 2006;44(3):88-92, 94. [ Links ]

5. Kahn D, Pillay S, Veller MG, et al. General surgery in crisis: comparatively low levels of remuneration. S Afr J Surg. 2006;44(3):96. [ Links ]

6. Couper ID. Recruiting foreign doctors to South Africa: difficulties and dilemmas. Rural Remote Health. 2003;3(1):195. [ Links ]

7. Sidley P. South Africa draws up new rules for foreign doctors. BMJ. 2000;321(7273):1368. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

B Sartorius

sartorius@ukzn.ac.za