Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Surgery

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5151

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2361

S. Afr. j. surg. vol.53 no.3-4 Cape Town dic. 2015

GENERAL SURGERY

Surgical resident working hours in South Africa

V Y Kong; J J Odendaal; D L Clarke

Pietermaritzburg Metropolitan Trauma Service, Department of Surgery, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Surgical training has undergone major changes worldwide, especially with regard to work hour regulations. Very little is known regarding the situation in South Africa, and how it compares with other countries.

METHOD: We conducted a retrospective review of the hours worked by surgical residents in a major university hospital in South Africa.

RESULTS: The attendance records of 12 surgical residents were reviewed during the three-month study period from January 2013 to March 2013. Ten were males. The mean age of the residents was 33 years. The mean total hours worked by each resident each month was 277 hours in January, 261 hours in February and 268 hours in March. The mean monthly total over the study period was 267 hours. This equates to approximately 70 hours per week.

CONCLUSION: The average surgical resident worked 70 hours per week in our unit. This was shorter than that in USA, but higher than that in Europe. There is likely to be a degree of heterogeneity between different training units, which needs to be explored further if a more accurate overall picture is to be provided.

Surgical training has experienced major changes in the past decades worldwide.1-3 Traditionally, it was based on an apprenticeship model. Trainees were required to spend unusually long hours in hospital, learning the "art and craft" of surgery.14 Long hours in the hospital were believed to be essential for continuity of patient care and the acquisition of clinical and technical skills.1,3,4 This paradigm has changed over the past three decades as a result of concerns about the effect of fatigue on patient safety, and owing to increasing emphasis on lifestyle issues in professional practice.5 Regulations have been introduced across Europe and the USA to regulate surgical trainee working hours.6,7 There is ongoing debate on the effectiveness of training with regulated hours.3,7,8 Currently, there are no regulations or guidelines governing the working hours of surgical trainees in South Africa. There is a paucity of literature documents the working hours of surgical trainees in South Africa. The last major study was carried out over a decade ago.9 The objective of this study was to review the actual hours worked by residents in a major university hospital in South Africa, and how this compared internationally.

Method

Setting

This was a retrospective study, conducted from January 2013 to March 2013 at the Pietermaritzburg Metropolitan Hospitals Complex (PMHC), Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Ethics approval to maintain the departmental surgical database, and for this study, was granted by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (Ethics Reference Number: BE 207/09). The Department of Surgery is an academic department under the auspices of the University of KwaZulu-Natal responsible for postgraduate training in general surgery, accredited by the Health Professions Council of South Africa, the national regulatory authority for medical licensing. The training programme in General Surgery is a total of four years. Our unit adopts a firm structure, whereby each speciality firm is led by a specific consultant surgeon. Surgical residents "rotate" every three months to a different firm in order to gain sufficient exposure to different surgical specialties.

Work pattern

"Normal work" hours commence at 07h00 and finish at 16h00 (nine hours). This is the expected number of hours that need to be worked from Monday to Friday. On-call duties are performed on site, i.e. physically within the hospital premises. Residents are not allowed to leave the premises during on-call duty, which begins at 16h00 and ends 20 hours later at12h00 the following day. Each surgical resident scheduled for on-call duty begins with his or her normal day duty at 07h00, but continues with their on-call duty at 16h00 on the same day. On-call duty times for residents on Saturdays are from 08h00-08h00 the following day (24 hours). Residents work from 08h00-12h00 the following day (28 hours) for on-call duties on Sundays. On-duty calls on public holidays are counted as either a "Saturday" on-duty call or a "Sunday" on-duty call, depending on which day the holiday falls. On-call duty usually occurs once every four days, depending on the number of staff rotating through each firm.

The study

A departmental record book is maintained by the hospital human resources department to monitor the working hours of medical staff. This is strictly enforced in the department. Each surgical resident who arrives at work is required to complete the start and finish time for each day. This is integrated into an electronic record for the department database. Residents who were on the duty roster, and not on annual leave during the study period, were eligible for inclusion.

Results

During the three-month study period, a total of 15 surgical residents were identified. Complete data were available for 12, so they were included in the study. (Three of the 15 were on annual leave). There were 10 males, with a mean age of 33 years. The mean total hours worked by each resident for each month was 277 hours in January, 261 hours in February and 268 hours in March. The mean monthly total over the three-month period was 267 hours. This equates to approximately 67 hours per week.

Discussion

Trainees are traditionally required to work unusually long hours during surgical training.1-3 This is considered essential so that trainees can acquire clinical and operative experience, and to provide continuity of care to patients.1,3 Over the past decade, increasing concerns have been raised about the contribution of doctor's fatigue (as a result of working for an excessive number of hours) to adverse events.5 There is also increasing emphasis on an appropriate work-life balance in professional life.10 What was once considered the "norm" in terms of work hours for previous generations of surgeons is less acceptable to current trainees.1,10 These changes have been most noticeable in the USA and Europe, where a number of regulations have been introduced, which have gradually restricted the work hours of surgical trainees.1,6

Historically, USA residents worked 95-136 hours per week.16 In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the organisation which regulates resident training in the USA, set a limit on an 80-hour week.6 Similar regulation by the European Work Time Directive (EWTD) was introduced in Europe, including the UK, in which the number of hours expected to be worked was reduced from 72 hours in 1991 to the current 48-hour week.7

It is obvious that reduced work hours have a positive impact on trainees' social well-being.10,11 Hutter et al. found that most surgical trainees working a 80-hour week reported a better quality of life, both in and out of hospital.11 However, there is ongoing debate on the appropriateness of such a restriction and its impact on the quality of surgical training.12

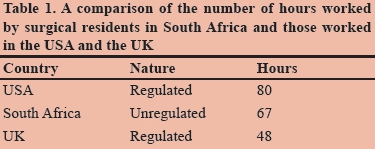

Kairys et al. reviewed the cumulative operative experience of residents in the UK with respect to restricted work hours, and demonstrated a noticeable decline in total operative case exposure, which was thought to have significant implications for the quality of training.13 Further concerns were raised by Bates and Slade with regard to the introduction of the EWTD further reducing the operative experience of surgical trainees to a degree in which it was impossible to achieve the level of competency required for the completion of specialist training.3 It was reported in a study Maisonneuve et al. that the majority of doctors in the UK did not agree that the EWTD had benefited the National Health Service.14 Those training in so-called "craft specialities", especially surgery, for which repeated exposure is required in order to gain technical experience, were the most negative about the EWTD in general.3,13 Proponents for working-hour restriction often cited patient safety as being the primary concern, yet studies from the USA found that restricted working hours did not result in a significant improvement in patient safety.15 Work hours in South Africa are compared with those in the USA and the UK (Table 1).

Currently, the working hours of surgical trainees in South Africa are unregulated. Working hours are set by each university-affiliated training unit. However, administrators frequently tend to place emphasise on service delivery over training and academic commitments.16 Nevertheless, understanding the current number of hours worked by trainees has significant implications on how future surgeons are trained, and are just as important elsewhere. In 2005, Vadia and Kahn, University of Cape Town, conducted the only local study to date in which at trainee work hours were examined. It was found in their study that trainees worked in excess of 100 hours per week.9 It was found in the current study that surgical trainees in our training programme worked hours that were more in line with those reported from the USA.

There is cognisance that the sample size in our study was limited, and an attempt was made to provide an accurate estimate of the hours worked by the surgical trainees. Invariably, there is a degree of heterogeneity between different training units across South Africa, not only in the hours worked, but also in how the duties are performed, e.g. onsite or offsite. Further studies are needed, in which the focus is specifically on surgical trainee work hours, in collaboration with those of different units around the country, to provide a better picture of the current situation with regard to South African surgical training.

Conclusion

The average trainee in our training unit worked approximately 70 hours per week. This is shorter than the reported hours in the USA, but higher than those in Europe. Invariably, there is a degree of heterogeneity between different training units, which needs to be explored further to provide a more accurate overall picture of the current situation in South Africa.

REFERENCES

1. Franzese CB, Stringer SP. The evolution of surgical training: perspectives on educational models from the past to the future. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2007;40(6):1227-1235. [ Links ]

2. Antiel RM, Van Arendonk KJ, Reed DA, et al. Surgical training, duty-hour restrictions, and implications for meeting the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies: views of surgical interns compared with program directors. Arch Surg. 2012;147(6):536-541. [ Links ]

3. Bates T, Slade D. The impact of the European Working Time Directive on operative exposure. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(4):451; author reply 452. [ Links ]

4. Walter AJ. Surgical education for the twenty-first century: beyond the apprentice model. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33(2):233-236. [ Links ]

5. Parker JB. The effects of fatigue on physician performance: an underestimated cause of physician impairment and increased patient risk. Can J Anaesth. 1987;34(5):489-495. [ Links ]

6. Gelfand DV, Podnos YD, Carmichael JC, et al. Effect of the 80 hour week on resident burnout. Arch Surg. 2004;139(9):933-940. [ Links ]

7. Morris-Stiff GJ, Sarasin S, Edwards P, et al. The European Working Time Directive: one for all and all for one? Surgery. 2005;137(3):293-297. [ Links ]

8. Moonesinghe SR, Lowery J, Shahi N, Millen A, Beard JD. Impact of reduction in working hours for doctors in training on postgraduate medical education and patients' outcomes: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342:d1580. [ Links ]

9. Vadia S, Kahn D. Registrar working hours in Cape Town. S Afr J Surg. 2005;43(3):62-64. [ Links ]

10. Troppmann KM, Palis BE, Goodnight JE, et al. Career and lifestyle satisfaction among surgeons: what really matters? The National Lifestyles in Surgery Today Survey. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(2):160-169. [ Links ]

11. Hutter MM, Kellogg KC, Ferguson CM, et al. The impact of the 80-hour resident workweek on surgical residents and attending surgeons. Ann Surg. 2006;243(6):864-871. [ Links ]

12. Vanderveen K, Chen M, Scherer L. Effects of resident duty-hours restrictions on surgical and nonsurgical teaching faculty. Arch Surg. 2007;142(8):759-764. [ Links ]

13. Kairys JC, McGuire K, Crawford AG, et al. Cumulative operative experience is decreasing during general surgery residency: a worrisome trend for surgical trainees? J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(5):804-811. [ Links ]

14. Maisonneuve JJ, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ. UK doctors' views on the implementation of the European Working Time Directive as applied to medical practice: a quantitative analysis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004391. [ Links ]

15. Poulose BK, Ray WA, Holzman MD. Resident work hour limits and patient safety. Ann Surg. 2005;241(6):847-860. [ Links ]

16. Thomson SR, Baker LW. Health care provision and surgical education in South Africa. World J Surg. 1994;18(5):701-705. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Damian Clarke

damianclarke@me.com