Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Surgery

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5151

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2361

S. Afr. j. surg. vol.51 no.3 Cape Town ene. 2013

PLASTIC SURGERY

A D RogersI; G dos PassosI; D A HudsonII

IMB ChB, Division of Plastic, Reconstructive and Maxillofacial Surgery, Department of Surgery, Groote Schuur and Red Cross War Memorial Children's hospitals and University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

IIMB ChB, MMed (Surg), FRCS, FCS (SA), Division of Plastic, Reconstructive and Maxillofacial Surgery, Department of Surgery, Groote Schuur and Red Cross War Memorial Children's hospitals and University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To ascertain junior doctors' awareness of the scope of public-sector plastic surgery practice.

METHOD: A 12-part questionnaire asked the respondents to name, from a list, the specialty they felt was best equipped to manage patients with specific conditions.

RESULTS: The data demonstrate that perception of the scope of plastic and reconstructive surgery is grossly limited. Although plastic surgeons were associated with reconstructive procedures, they were not necessarily identified as primary surgeons for procedures that they commonly perform. A significant number of respondents believed that plastic surgeons are seldom the first line of referral, and are more involved in cases with aesthetic rather than functional sequelae.

DISCUSSION: These findings should be regarded with concern, particularly in light of the fact that these doctors will be responsible for carrying the burden of primary care delivery in South Africa and for referrals to secondary and tertiary levels of care. The study motivates for increased exposure to plastic surgery during undergraduate and postgraduate medical training.

'The great enemy of the truth is not the lie - deliberate, contrived and dishonest, but the myth - persistent, persuasive and unrealistic. Belief in myths allows the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.'

- John F Kennedy

Although plastic surgery has been performed for thousands of years, a well-defined specialty (and formal training programmes) remained elusive well into the 20th century. Sushruta, who described more than 300 procedures and 120 instruments in Sushruta Samhita and is widely regarded as the 'Father of Surgery, made important contributions to reconstructive surgery in 6 BC.[1] Plastic surgery is a dynamic and evolving specialty, not restricted by anatomy or organ system, incorporating heterogeneous disciplines (hand surgery, maxillofacial trauma, skin cancer, trauma reconstruction, burns, aesthetic surgery, oncology reconstruction, cleft surgery, etc.). Plastic surgery has evolved to contribute in many complex areas previously managed by other specialties. In an era of increasing sub-specialty training in other areas of surgery (especially general surgery), plastic surgeons are arguably the 'general surgeons' of the 21st century. But the specialty's greatest asset, its versatility, may also have been its undoing. The extent of plastic surgery is underestimated by all but those within the specialty. This study aimed to ascertain junior doctors' perceptions of the scope of public-sector plastic surgery practice in South Africa.

Methods

In order to assess recent medical graduates' knowledge of the scope of plastic surgery, 33 house officers (representing a spread of all of South Africa's medical schools but currently employed at the hospital complex incorporating Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital and Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town) were asked to complete a questionnaire. They were required to select, from a list, the specialist best equipped to manage 12 common clinical problems.

The questionnaire (Fig. 1) was not intended to be an exhaustive demonstration of the breadth of plastic surgery, and some conditions not expected to be first line were also included. The respondents were permitted to offer both a first- and a second-line specialty. The first line selected should be the specialist who would co-ordinate the care of the patient and deliver the most significant contribution. A second line could also be selected -another specialist who may deliver an equivalent service, or play a significant supplementary role. The respondents were encouraged to make further comments regarding their understanding of the scope of practice of plastic surgery.

Results

Many respondents believed that plastic surgeons are seldom the first line of referral, and are more involved in cases with aesthetic rather than functional sequelae. Although many of them recognised the reconstructive role that plastic surgeons play, e.g. in the management of burns and paediatric congenital conditions, plastic surgery did not feature prominently in several of its other core disciplines, notably hand surgery, maxillofacial trauma and skin cancer.

The first-line contribution to the management of burns and paediatric congenital conditions, as well as the supplementary role in comprehensive breast cancer therapy, was well recognised by the respondents. However, plastic surgeons were not regarded as the first line in the management of several clinical scenarios, most notably maxillofacial trauma, cutaneous malignancies and hand surgery. Only 36.4% (n=12) of those questioned considered that plastic surgeons commonly manage hand conditions (either first or second line), only 27.3% (n=9) regarded plastic surgeons as able to manage maxillofacial trauma (all second line), and only 33.3% (n=11) viewed the specialty as first-line specialists for skin cancer management. About one-third (n=12) of respondents believed that plastic surgeons were the primary managers of children with cleft lips and palates. The results are represented in Fig. 2.

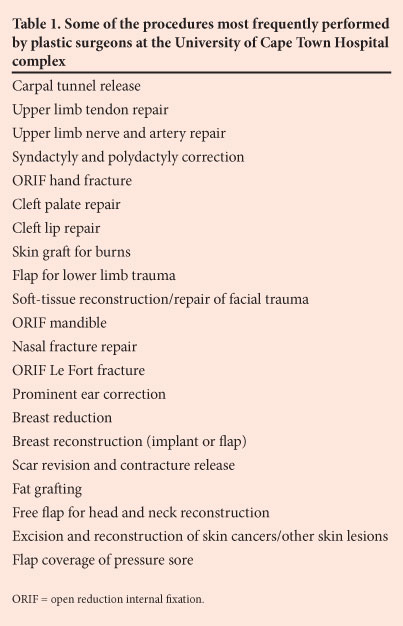

Fig. 3 illustrates the approximate time (as a percentage of total time) spent in each discipline by registrars training in plastic surgery at the University of Cape Town hospital complex. Less than 5% is dedicated to managing patients with purely aesthetic considerations, while a large proportion is spent on burns and trauma, especially of the limbs and face, as well as excision and reconstruction for neoplasms, especially of the skin and soft tissue, breast, and head and neck. Table 1 provides a list of some of the procedures most frequently performed by plastic surgery staff in this setting.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that house officers' perception of the scope of plastic and reconstructive surgery is grossly limited. Although plastic surgeons are associated with reconstructive surgery, they are not recognised as primary surgeons for many of the procedures fundamental to their specialty.

Undergraduate medical students are seldom exposed to several of the disciplines in plastic surgery, regardless of their prevalence. All cleft lip and palate surgery, for example, is performed in this hospital complex by plastic surgeons. Maxillofacial trauma comprises a significant proportion of the function of plastic surgery trainees here, and together with hand surgery constitutes about 30% of this unit's clinical workload and as much as half of the after-hours work. About 25% of plastic surgical training in this complex is spent managing hand problems (adult and paediatric, trauma, hand burn reconstruction and congenital hand abnormalities).

After prominent ear correction and burns, the respondents in this study regarded management of bedsores as the next most recognised reason to refer a patient to a plastic surgeon. Plastic surgeons are equipped, using techniques on the 'reconstructive ladder', to address complex wounds involving any part of the body, and are therefore frequently consulted by other surgeons for assistance with and salvage of complications (e.g. dehisced sternal and caesarean section wounds or infected vascular grafts in the groin). Plastic surgeons are frequently required to offer important supplementary or complementary roles in the management of patients with a variety of problems. This concept was recognised by some respondents, most notably in the management of breast cancer and eyelid problems, but disciplines regarded by plastic surgeons as integral to the specialty (skin cancer and hand surgery) were not viewed similarly. These findings should be regarded with concern because: (i) this group of doctors should have more contact with plastic surgeons in the academic hospital setting than in any other; and (ii) they will be responsible for carrying the burden of primary and secondary care delivery in South Africa, and for referrals to higher levels of care.

Several studies have demonstrated that both the public and fellow medical graduates have a skewed understanding of the scope of practice of plastic surgeons.[2-12] Gill et al., for instance, performed a cross sectional survey of the Australian public. Dermatologists were selected ahead of plastic surgeons to excise skin cancers, breast surgeons were preferred for breast reductions, and orthopaedic surgeons were consistently selected for the management of hand complaints.[7] Park et al. demonstrated that the public and even medical graduates develop much of their understanding of plastic surgery from the media. Popular television programmes (e.g. 'Nip-Tuck', 'Dr 90210, 'Extreme Makeover, etc.) have created the impression that aesthetic surgery is the dominant component of the specialty, when the reality is quite different, particularly in the state sector.[8]

Other surgical specialties have expressed similar concerns with respect to disproportionate exposure at undergraduate level, probably as a result of the dominant role that general surgeons have maintained in determining undergraduate surgery teaching. Ophthalmologists, for instance, have long maintained that the proportion of undergraduate training dedicated to their specialty is out of keeping with the clinical load.[9,13] Bizarrely, students are far more likely to be able to describe a Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy accurately than they are cataract surgery, regarded as one of the most frequently performed and most cost-effective procedures (measured in quality-adjusted life years).[14]

The specialty of plastic surgery is underestimated in a number of different ways, and similar sentiments have been expressed globally, but misconceptions continue to be propagated, often by other surgeons, who themselves have had insufficient exposure to plastic surgery. Many outside the specialty are surprised to learn that in spite of the variety and volume of operative cases performed, plastic surgery units also add value to the service offered by allied surgical specialties, and utilise a relatively small portion of budgets allocated to surgical services as a whole. A recent study by Wang et al. emphasised the economic value to hospital profitability of plastic surgery units in the USA. While demonstrating a greater than average 'surgeon total relative value' (a measure of productivity as primary surgeons), approximately one-third of procedures by plastic surgeons were performed in collaboration with other surgical disciplines (e.g. free-flap reconstruction for neoplasms or salvaging a complication). These joint or salvage procedures were seldom logged as 'plastic surgery' by hospital administration, and consequently imbalanced policies, staff and funding are determined.[15]

Plastic surgery's heterogeneity has both helped and hindered the specialty. While cosmetic surgery has been glamourised by the media, in performing their reconstructive duties plastic surgery units have frequently been under-resourced, under-funded and under-staffed. Consequently, many surgical departments have fallen victim to misconceptions and have failed to recognise the specialty's multidisciplinary contributions.

This study demonstrates that plastic surgeons are not identified (even by qualified doctors) as the primary surgeons for procedures fundamental to the specialty. The study motivates for increased exposure to plastic surgery at undergraduate and postgraduate level. It also places the onus on plastic surgeons to reverse the misconceptions that abound among their peers.

Conclusion

This questionnaire-based study demonstrates misperceptions held by house officers of public sector plastic surgical practice in South Africa. It is considered to be a revealing window into the perceptions of broader groups, including medical doctors in general, the public, politicians and the media.

Plastic surgery is a broad surgical specialty comprising seemingly unrelated disciplines, not limited by organ system or pathology but instead linked by a systematic approach to many of the more difficult and intricate problems previously managed by others. The advent of, and increasing demand for, cosmetic surgery has undoubtedly influenced the way in which the specialty is viewed by others, but critics will do well to remember the many positive influences cosmetic surgery has had on the quality and effect of reconstructive surgery, the priority of public sector plastic surgery units.

Plastic surgery is best considered with all of its many faces, including (among others) hand surgery, facial aesthetic surgery, maxillofacial trauma, complex wound care, breast surgery, skin cancer, cleft surgery, microsurgery and burns. It is a fascinating and challenging field of medicine, arguably the most 'general' of surgical specialties. This study motivates for increased exposure to plastic surgery at both undergraduate and postgraduate level.

REFERENCES

1. Saraf S, Parihar RS. Sushruta: The first plastic surgeon in 600 B.C. Internet Journal of Plastic Surgery 2007;4(2). [ Links ]

2. Widgerow AD. Plastic surgery - more than just a nip and a tuck. S Afr Med J 1994;84(1):7. [ Links ]

3. Zaman MJS. We don't need another 400 plastic surgeons (and replies to above, 5 January 2007 - 19 March 2007). BMJ 2007;334(7583):44. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39055.393542.591 [ Links ]

4. Tanna N, Patel NJ, Azhar H, Granzow JW. Professional perceptions of plastic and reconstructive surgery: What primary care physicians think. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;126(2);643-650. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181de1a16] [ Links ]

5. Kim DC, Kim S, Mitra A. Perceptions and misconceptions of the plastic and reconstructive surgeon. Ann Plast Surg 1997;38(4):426-430. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000637-199704000-00020] [ Links ]

6. Dunkin CS, Pleat JM, Jones S, Goodacre T. Perception and reality: A study of public and professional perceptions of plastic surgery. Br J Plast Surg 2003;56(5):437-443. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0007-1226(03)00188-7] [ Links ]

7. Gill P, Bruscino-Raiola F, Leung M. Public perception of the field of plastic surgery. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery 2011;81(10):669-672. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2011.05753.x] [ Links ]

8. Park AJ, Scerri GV, Benamore R, McDiarmid JGM, Lamberty BGH. What do plastic surgeons do? J R Coll Surg Edinb 1998;43(2):189-193. [ Links ]

9. Roswell AR. The place of plastic surgery in the undergraduate surgical curriculum. Br J Plast Surg 1986;39(2):241-243. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0007-1226(86)90090-1] [ Links ]

10. Rohrich RJ. Plastic versus cosmetic surgery: What's the difference? Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;106(2):427-428. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200008000-00029] [ Links ]

11. Zook E. Where should the battle to improve the speciality's image be fought or won? Plastic Surgery News 1993;6:2. [ Links ]

12. Hallock GG. Plastic surgeon: Asset or mere mercenary? Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;108(2):568-570. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200108000-00047] [ Links ]

13. Van Zyl, LM, Fernandes N, Rogers GJ, Du Toit N. Primary health eye knowledge among general practitioners working in the Cape Town metropole. South African Family Practice 2011;53(1):52-55. [ Links ]

14. Lansingh VC, Carter MJ, Martens M. Global cost-effectiveness of cataract surgery. Ophthalmology 2007;114(9):1670-1678. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.12.013] [ Links ]

15. Wang TY, Nelson JA, Corrigan D, Commack T, Serletti JM. Contribution of plastic surgery to a health care system: Our economic value to hospital profitability. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012;129(1):154-160e. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182362b36] [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A D Rogers

(rogersadr@gmail.com)