Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Science

versão On-line ISSN 1996-7489

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.119 no.11-12 Pretoria Nov./Dez. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2023/16546

BOOK REVIEW

https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2023/16546

Undoing Apartheid's mechanisms of reproductive power

Nancy Luxon

Department of Political Science, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. Email: luxon@umn.edu

Book Title: Undoing apartheid

Author: Premesh Lalu

ISBN: 9781509552825 (hardback, GBP50, 202pp); 9781509552832 (paperback, GBP18, 202pp); 9781509552849 (ebook, GBP17, 202pp)

Publisher: Polity, Cambridge, UK

Published: 2022

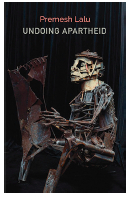

The arresting image on the cover of Undoing Apartheid - the sculpture "Read, man, Read!" by Chumisa Fihla -perfectly captures the provocative thesis of author Premesh Lalu. Namely, that some humans, engineered through technological bits and pieces, have come to find their sensory and material existence defined by the mechanising logic of petty apartheid. The sculpture thus evokes the gestuary or repertoire of petty apartheid: the intrusion into everyday existence of a mechanical form of life, one that lodges itself in circuits of sense and perception. Lalu's book offers a remarkable exploration of the subjectivity that came to accompany the broader, systemic features of apartheid in South Africa, and its continued reproduction in a post-apartheid world. To analyse the intersection of structure and subject, Lalu turns away from the grand apartheid familiar to most: the ideology of racial separation and the political acts of relocation and partition into ethnically defined homelands and racially defined Group Areas (p.27). Instead, he focuses attention on petty apartheid, or the system that controlled the minutia of everyday life. On his read, this daily life reflects more than the technical application of grand apartheid. It becomes a way to impel human beings to a "becoming mechanical", that is, to adapt increasingly mechanised forms of life that stifle desire and creativity. Despite changes to a legal code or political order, apartheid comes to persist in the reproduction of the everyday. As a result, apartheid becomes difficult to surpass or move beyond; differently put, "undoing apartheid" is a labour in itself, one to be held as distinct from efforts to supersede it. To read the world on new terms means infusing acts of interpretation with a desirous creativity that might interrupt the mechanical circuits laid down through petty apartheid.

Undoing Apartheid is organised around six chapters and covers a surprising amount of terrain. After a synoptic introduction, the second chapter takes seriously the "far-fetched mythic claims" (p.33) invoked to justify South African racist ideology through the origin stories told by Afrikaner nationalists, and considers how myth connected the technical system of slavery to that of industrialisation; simply debunking racial myths does not undo the economic rationales of efficiency that allowed racial domination to be quietly subsumed under industrialisation. Through a reading of Goethe's Faust against William Kentridge's Faustus in Africa, Chapter 3 traces the reconstitution of race - beset by conflicts between human, nature, and technology - as a collection of sense perceptions that consigns some to a mechanical existence able only to service (but never to be integrated into) the whole. Chapter 4 is the heart of the book, and narrates this psychological story as one that results in a subjectivity "whose sensory world has all but collapsed as a result of a sheer mechanization of life that strips individuals of desire, striving, and futurity" (p.103). Not only does a shrunken sensorium ease the meld between human and machine, it also transmutes perception into apperception by robbing people of the raw materials, that Freudian Rohstoff, that fuels invention, imagination, and fantasy. For there to be an "after" to apartheid, one that is an emancipation from not just the partitions of grand apartheid but also those of sense perception, requires undoing apartheid subjectivity at the juncture where senses and technology facilitate a relation to power.

Resisting a turn to affect theory, Lalu instead explores the aesthetic education offered through "stumbling" (p.150-): first the stumbling of a slapstick theatre that uncouples technology and mythic violence, and then the reworking of the division between sense and perception so as to imagine new futures and new experiences of freedom. "Undoing apartheid," concludes Lalu "thus requires setting to work on...crafting a workable concept of reconciliation, one capable of relinking sense and perception and staking a claim to truth content on its own terms" (p.187). It is work, insofar as it must slowly unravel the use of technology to maintain these links and to give these modern, neoliberal times the "meaning" of efficiency. Work, then, is deeply linked to political subjectivity rather than a Marxist class consciousness or an unalienated labour. It is the effort to render visible the divisions that sustain racial inequality, and the dependence on the immaterial labour of a racialised other (p.92).

Crucial to the iterability of apartheid is the double-take, or the uncanny doubling of its feelings, its patterns, and its reproductions (p.23, p.118). Undoing Apartheid is organised around a series of double-takes - the history of Athlone, at once a town in central Ireland, the name of the last British governor for South Africa, and a Cape Town district formed by the forced removals. Another is the repetition of the Trojan horse story, as voiced by Seamus Heaney in The Cure at Troy (and introducing the theme for each chapter), and its entwinement with the Trojan Horse massacre of 1985 in which anti-government students living in Athlone were ambushed by security forces. A third, already mentioned, is the reprisal of the Faust story. This panoply of figures serve as the mythic precursors for a racialised modernity that compresses the distance between the Global North and South, and that complicates any effort to separate this history or its archive. In contrast to those who distinguish the histories of the Global North and South - yet another division - Lalu does something refreshingly different with this history. He emphasises this uncanny as one that compresses time so as to conflate past, present, and future. Yet these doublings are not recuperative - with one an example of a flawed history, the other a modern update that "gets it right" - but rather an opportunity to glimpse how the fantastical becomes real, and how that reality might subsequently be dislodged. The turn to puppetry (Kentridge's Faustus is performed by Handspring Puppet Theater), shifts this intervention into the genealogy of race away from the register of mere representation and towards the register of labour: "The puppet is an uncanny prosthesis: one that conveys a sense of spirit, and that abides neither by received ideas of truth nor by premature declarations of reconciliation" (p.77). Static representation is replaced by dynamic process. Neither fully inanimate (the puppet master is all-too-visible) nor fully animate (it is, after all, a manipulated wooden object), the puppet challenges its viewers to reach "into a metaphysical core...of political transition" and to attend to the process of making and its interdependencies, rather than the telos of history's tragedy or redemption. The result is a gloriously complex approach to the making and unmaking of history in all its geographical and temporal sprawl.

Lalu's account also gives his readers a provocative way of thinking change. Scholars have recently moved on from critiques of progress or enlightenment, and have instead sought to identify patterns key to racism's persistence and recurrence over time. Rather than striding confidently forward and past economic underdevelopment or failed nation states, Lalu asks his readers to linger on how they have stumbled - on how they have stumbled to move beyond the debunking of racist ideologies, or beyond a critique of "failed progress" - and to search out the time-ing that would let them catch themselves and recalibrate interpretations. The emphasis on time-ing is more than (yet another) historical turn. Lalu argues that historicisation can only go so far in undoing racism, as the historicising move presumes that racism is irrational (p.59). As a result, historicisation struggles to identify those rationales that made the reconstitution of race so, well, seemingly reasonable. Instead, the appeal to time-ing is an appeal to context and the material logics that organise particular experiences (p.64). What would it mean to abandon the search for the "best" form of governance or the "right" representations? How might we sidestep existing determinate logics? Again, in raising questions about "what next?" many might luxuriate in affect, revel in the aesthetics of ambiguity, or seek to unmask through genealogy. Each of these responses, however, marks a turn away from relations of power, away from political agency, and away from the messy work of politics. In keeping an eye insistently on technologies of power, Lalu redirects us to the work of building something and in a way that places craft, formation, and productivity back in the hands of ordinary people. Rather than being beguiled by spectacle and unseeing to the puppet masters' manipulations, what would it mean to place the crafting of human beings (with their unsteady admixture of in/animation and in/ dependence) in plain sight? How might people be taught or provoked to sense, perceive, and so act on different terms?

Such a framing of race as caught between the ambivalence of science and nature is an unusual way into a discussion of race and racial division. The Faustian wager is "rearticulated, so that colonialism is less a regressive accompaniment of global capitalism than a prognosis of that specific future of capital built on drives in which divisions between human and machine are rendered indistinct" (p.75). Lalu thus dispenses with theories of race that rely either on essential origins or the debunking of biological racism through reason that leads inevitably to progress. Instead, he reads late modernity on the terms of what Michelle Alexander has called "racism without race". Gesturing to a few landmark moments in late modernity's turn to technology, Lalu writes that "race is that excess of slavery transferred to a technological milieu, where this milieu operationalizes, distributes and controls its signification ... this technological milieu is infused with mythic content in the colonial world" (p.54). Rather than rooting racism and race thinking in intention, genetics, ideology, or structure alone, Lalu instead gives us the causality of "consilience", or the unexpected convergence of physics and psychology, science and nature, and of affect and reason (p.7, p.97). This proposal is unexpected and cries for more elaboration. After all, Alexander's "racism without race" poses a thorny political problem: how can racism be named and called out, if racial outcomes cannot be clearly

linked to racist logics or the intentions of obvious villains? Lalu's appeal to consilience similarly unsettles: if the unlikely convergence of faculties organises what is possible to think, then mobilising any political response requires first creating awareness of a problem. The sharp insight here is that such awareness can leave behind the tired categories of "identity politics", "authenticity", and "recognition" to instead concentrate on the materiality of the situation at hand, and to ask how and why certain divisions came to have organisational force.

Lalu's emphasis on the conjoinment of the sensorial and material offers a striking change from other approaches to thinking race that might rely either on affect theory, the critical ontology of Afro-pessimism, or phenomenology. For all that Lalu wants to "re-enchant the desire for post-apartheid freedom" (p.7), he does not propose a sensorial or affective turn to counter the mechanical and rote and he dismisses Afropessimist accounts of an ontology rooted irredeemably in racial difference as historically (and politically) conservative. To recall, this workable reconciliation "relinks sense and perception and stakes a claim to truth content on its own terms" (p.187). Yet this reconciliation is no rainbow coalition; Lalu dismisses such "rainbowism" in the very next sentence. "Reconciliation" speaks to the process of undoing the work of "consilience". It is a worlding that seems to take its inspiration from Canguilhem rather than Heidegger in that it aims to develop the capacity to tolerate variations in norms (rather than their integration into a cohesive whole).

The appeals to worlding and truth content sparks a desirous question: Beyond the practical work of undoing, what vision of freedom orients and sustains those who set it up? It certainly is not the transcendence of liberation, nor the inclusion of integration into liberal order. Lalu invokes the cinema as a way to illustrate the experience of an interval suspended between one present order and another yet to come. If petty apartheid allows for the mechanical repetition of apartheid's gestures and patterns of interaction, then what would it mean to interrupt it? How might memories be reconnected to different futures, and how might the unconscious differently attach to new symbolic forms? Although I am persuaded that this retooling must also be a reschooling, I'm left wanting more about the substance of this freedom. Such substance holds value because of who and how its mobilises, and how these unexpected collisions redirect technologies of power in unexpected ways. Lalu regrets that too often the intensity associated with the 1985 student movement becomes confused with a simplistic mobilisation of outrage as in #RhodesMustFall. Fanon and others have noted that racial division is an easy shortcut to political mobilisation, not just for colonisers but also for the colonised. He called for a renewed attention to deepening relationships and reciprocities between elites and masses as a path to the figuration of his own 'New Man'. I finished this book wondering in which relations of power Lalu's aesthetic education should be lodged, and oriented toward which normative and political ideals? What sites, and with what proximity to institutional power, might conjure new freedom dreams and give them the mass and corporeality they need to endure? Toward thinking through these questions, Undoing Apartheid offers an unexpected, unorthodox, and deeply rewarding read.

Published: 29 November 2023