Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Science

On-line version ISSN 1996-7489

Print version ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.117 n.7-8 Pretoria Jul./Aug. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2021/9438

RESEARCH LETTER

Implications of new AMS dates for the Khami Period in the Mapungubwe Landscape

Thomas N. HuffmanI; Stephan WoodborneI, II

IGeography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIiThemba LABS, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

After the abandonment of Mapungubwe, the Limpopo Valley was reoccupied first by Sotho people, making Icon pottery, and then by Kalanga speakers making Khami pottery. The senior Kalanga chief, in this case Twamamba, was based at Machemma about 60 km to the south, while several petty chiefs administered various portions of the valley itself. Because of fluctuating rainfall, the occupations of both Sotho and Kalanga people occurred in pulses during higher rainfall periods. New AMS dates place one site in the Icon Period, eight sites in Pulse 1 (AD 1400-1480) and eight sites or components in Pulse 2 (AD 1520-1590). Kalanga people occupied the best agricultural land near the Limpopo floodplains and Sotho people lived on the plateau to the south. The two groups thus shared the landscape, but not the resources equally. The ceramic record documents this unequal interaction. This interaction, facilitated by male and female initiation schools on the ethnic boundary, helped to create Venda as a language and macro-cultural entity.

SIGNIFICANCE:

• Interaction between Sotho (Icon) and Kalanga (Khami) over some 200 years led to the creation of Venda.

• New radiocarbon dates relate to Tshivenda origins, the language spoken by Venda today.

• Initiation schools in the Limpopo Valley provide a model for interaction in the rest of Venda.

Keywords: ceramic proxies, Khami state, Limpopo Valley, rainfall fluctuations, Sotho-Kalanga interaction, Venda origins

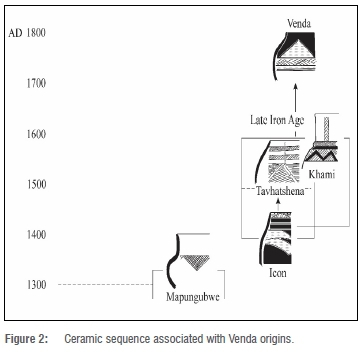

By AD 1320, Mapungubwe people had abandoned the Limpopo Valley and the landscape remained unoccupied by agriculturalists for some 80 years until early Sotho people took up residence.1,2 With a probable origin in East Africa3, Icon pottery marks the first appearance of Sotho speakers in southern Africa. Shortly afterwards, Kalanga speakers (Western Shona) who made Khami pottery moved south from Zimbabwe and reoccupied the valley: it was their ancestors who had lived at Mapungubwe.

The Khami Period

Khami chiefdoms can be ranked according to a hierarchy in which each chiefly level was the apex of a pyramid of lower courts.4 Between AD 1400 and 1450, Khami5 near Bulawayo (Figure 1) became the large capital of an independent Torwa state in an area known as Butua6. States with such large capitals encompassed some 90 000 km2 and multiple smaller chiefdoms. In the early 15th century, Khami expanded its control into Botswana7, southern Zimbabwe8 and across the Limpopo. The senior chief for the Limpopo settlements was based at Machemma9, about 60 km to the south of the Limpopo. A paramount chief at this time did not exist in South Africa nor in Botswana, and so, the provincial capital must have been in Zimbabwe.

Because Shona and Venda people use natural features to mark political boundaries10, the Shashi and Limpopo rivers most likely separated the southwest (Botswana) and southern (South Africa) districts from those in Zimbabwe. Interaction between early Sotho and Kalanga appears to have occurred only in the southern district and further southeast. Kalanga people withdrew during the dry period around AD 1500 and then returned to the Limpopo, and to Machemma, when rainfall improved.10

Sotho and Kalanga interaction in the Mapungubwe Landscape

Interaction between Sotho and Kalanga peoples is of special interest because it led to the creation of Venda as a language and macro-cultural entity. Venda people are archaeologically and anthropologically important because they have continued the essence of the pre-colonial Zimbabwe Culture - class distinction and sacred leadership -distinguishing them further from Sotho- and Nguni-speaking communities.11

The Tshivenda language is known to be a unique blend of Shona (both Kalanga and Karanga) and Sotho.12 Previous research near the Soutpansberg shows that the creation of Tshivenda parallels the creation of Letaba (Venda) ceramics from a blend of Icon (Sotho) and Khami (Kalanga) pottery.13

It is not possible to use ceramic data alone to identify which, if any, present-day Sotho and Kalanga dialects were spoken 600 years ago. Broad correspondences between Icon and Sotho, and Khami and Kalanga, are nevertheless sufficient for our Limpopo research.

Foot surveys in the Limpopo Valley have recently yielded some 398 sites with Icon (95) and Khami (285) pottery, plus some with both (18) (Figure 2): Khami people occupied the best agricultural land, demonstrating their political dominance. The sites belonged to two main pulses: Pulse 1 in the 15th century and Pulse 2 in the mid-16th century. Isotopic analyses of the rings of four baobab trees (with ±5-year ring accuracy) show that these two pulses experienced relatively high and sustained rainfall separated by dry conditions inimical to farming.14

New dates

We have recently processed dung samples from 16 new sites or components related to Venda origins. They were collected from below the surface level inside central cattle kraals: eight in Pulse 1 and eight in Pulse 2 (Table 1). We use the southern hemisphere data set SHCal20 at one sigma accuracy, following Calib 8.10 (available online at http://calib.org/calib/calib.html). We use one sigma errors rather than two because each dung sample derives from a short, discrete dating event limited by our tight ceramic and baobab sequences. Our sequence confirms that recorded by Loubser13: a few Icon sites date to the beginning of the 15th century (e.g. Edmondsberg site AD 161); then sites with Khami pottery, or Khami with Icon, date to Pulse 1 (e.g. Machemma DC1); and Khami and Tavhatshena date to Pulse 2 (e.g. DS 32). Tavhatshena pottery is similar to Icon (and difficult to distinguish), but with the addition of Khami motifs. Indeed, Icon and Khami motifs occasionally occur together on the same vessel surface. The third and final step in the creation of Venda ceramics, tetaba, is not present in the Limpopo Valley until the 19th century, after it evolved elsewhere. This third step is not part of the Limpopo sequence because it was too dry for farmers to live there after Pulse 2.

Initiation schools

Loubser's13 research suggested that the Soutpansberg was the boundary between Shona speakers to the north and Sotho speakers to the south. Our survey shows that the initial interaction took place in more confined localities, such as the Mapungubwe Landscape. The channel for this interaction was probably through initiation schools. Such schools as domba inculcate various aspects of culture, including history, worldview and proper moral behaviour15-18, and both royal and commoner youths attend. It is therefore significant that the remains of these schools stretch along the boundary between Khami and Icon settlements (e.g. Faure AD 2 and Kilsyth AD 268) and nowhere else in the Mapungubwe area. They are not located in the centre as researchers once thought.10 The new dates show that these schools date to both Pulse 1 and Pulse 2, when Icon changed to Tavhatshena. In addition, male circumcision sites occur on the eastern boundary associated with the Khami-Period palace called Haddon.9,19 Both types of schools were therefore present in the valley at the same time, and over the years, hundreds of youth would have attended both. These schools provide a model for interpreting Tshivenda origins in the rest of Venda.

End of Khami

In AD 1644, the Khami capital was destroyed by a combined force of Portuguese and a disgruntled faction of the Torwa state20, and for the next 40 years, no single leader controlled the former kingdom. A few chiefs controlled some areas in Botswana21, but none appears to have been based in in the Limpopo Valley, perhaps because this Interregnum Phase was too dry. The third step in the evolution of Tshivenda took place at this time, when Butua lacked strong leadership.

Strong leadership was reinstated when the Rozvi established a new capital at Danangombe22 (formerly Dhlo Dhlo) in the 1680s20. This new state did not expand to the south but instead defeated the Portuguese to the east and northeast. When the famous Rozvi leader, Changamire Dombolakonachingwano, died in 1696 after defeating the Portuguese, at least three sons competed for kingship. One unsuccessful son went to the Hwange area to give rise to the Nanzwa23 and another crossed the Limpopo to establish the Singo capital at Dzata in present-day Venda24. Some researchers25 consider the Singo as 'true Venda', but as Loubser's13 archaeological research shows, Venda language and identity had evolved before the Singo established Dzata. Once there, the Singo forged a new state, incorporating the Khami-Period chiefdoms that extended east from Machemma. Letaba pottery and Venda walling at the top of the Machemma sequence documents this change.10 Somewhat later, the Tshivhula dynasty of the Twamamba built a new headquarters at Mavhambo at the base of the Soutpansberg (Figure 3).13 The Tshivhula claim that their territory once extended from Machemma to the Limpopo.26 Because each chiefdom level is two to three times the size of the level below, Machemma would have controlled about 10 000 km2, corresponding to the area claimed by the Tshivhula. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that the Khami Period in the Mapungubwe Landscape marks the arrival of the Tshivhula dynasty, or at least the Twamamba.10 Originally, they would have spoken Kalanga, but by the 17th century, they had become Venda and independent of the Khami state.

Acknowledgements

We thank Myra Mashimbye, McEdward Murimbika, Justine du Piesanie and Peter Venter for their help with the surveys, excavations and specialist studies. Gavin Whitelaw commented on earlier drafts. The University of the Witwatersrand Honours classes of 2000 to 2009 also participated in the research. Wendy Voorvelt prepared the illustrations and Moshabi Silidi and Stephan Winkler processed the AMS dates. Fieldwork was sponsored by the University of the Witwatersrand Research Incentive Scheme (Huff013). Excavations were conducted under the South African Heritage Resources Agency permits (numbers 80/05/04/017/51, 80/06/05/007/51 and 80/08/04/019-021/51).

Competing interests

We have no competing interests to declare.

Author's contributions

T.N.H. directed the fieldwork and S.W. the AMS dating. Both authors helped prepare the manuscript.

References

1. Huffman TN, Woodborne S. Archaeology, baobabs and drought: cultural proxies and environmental data from the Mapungubwe Landscape. Holocene. 2016;26(3):464-470. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683615609753 [ Links ]

2. Huffman TN, Woodborne S. New AMS dates for the Middle Iron Age in the Mapungubwe Landscape. S Afr J Sci, 2021;117(3/4), Art. #8980. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2021/8980 [ Links ]

3. Louw JA, Finlayson R. Southern Bantu origins as represented by Xhosa and Tswana. S Afr J Afr Languages. 1990;10:401-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/02572117.1990.10586873 [ Links ]

4. Huffman TN. Archaeological evidence and conventional explanations of Southern Bantu settlement patterns. Africa. 1986;56(3):280-298. https://doi.org/10.2307/1160685 [ Links ]

5. Robinson KR. Khami ruins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1959. [ Links ]

6. Van Waarden C. Butua and the end of an era. The effect of the collapse of the Kalanga State on ordinary citizens: An analysis of behaviour under stress. BAR International Series 2420. Oxford: Archaeopress; 2012. https://doi.org/10.30861/9781407310190 [ Links ]

7. Campbell A, Kinahan J, Van Waarden C. Archaeological sites at Letsibogo Dam. Bots Notes & Records. 1996;28:47-53. [ Links ]

8. Manyanga M. Resilient landscapes: Socio-environmental dynamics in the Shashi-Limpopo Basin, Southern Zimbabwe c. AD 800 to the present. Studies in Global Archaeology 11. Uppsala: Department of Archaeology and Ancient History; 2007. [ Links ]

9. Huffman TN, Hanisch EOM. Settlement hierarchies in the northern Transvaal: Zimbabwe ruins and Venda history. Afr Stud. 1987;46:79-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020188708707665 [ Links ]

10. Huffman TN, Du Piesanie J. Khami and the Venda in the Mapungubwe Landscape. J Afr Archaeol. 2011;9(2):189-206. https://doi.org/10.3213/2191-5784-10197 [ Links ]

11. Huffman TN. Snakes & crocodiles: Power and symbolism in ancient Zimbabwe. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press; 1996. [ Links ]

12. Lestrade GP Some notes on the ethnic history of the BaVenda and their Rhodesian affinities. S Afr J Sci. 1927;24:486-495. [ Links ]

13. Loubser JHN. The ethnoarchaeology of Venda speakers in southern Africa. Navors Nas Mus Bloemfontein. 1991;7(7):162-167. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/AJA00679208_2841 [ Links ]

14. Woodborne S, Hall G, Robertson I, Patrut A, Rouault M, Loader N, et al. 1000-year carbon isotope rainfall proxy record from South Africa baobab trees (Adansonia diagata L). PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5), e0124202. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124202 [ Links ]

15. Blacking J. Songs, dances, mimes and symbolism of Venda girls' initiation schools. Part 1: Vhusha. Afr Stud. 1969;28(1):3-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020186908707300 [ Links ]

16. Blacking J. Songs, dances, mimes and symbolism of Venda girls' initiation schools. Part 2: Milayo. Afr Stud. 1969;28(2):69-118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020186908707306 [ Links ]

17. Blacking J. Songs, dances, mimes and symbolism of Venda girls' initiation schools. Part 3: Domba. Afr Stud. 1969;28(3):149-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020186908707309 [ Links ]

18. Blacking J. Songs, dances, mimes and symbolism of Venda girls' initiation schools. Part 4: The great Domba song. Afr Stud. 1969;28(4):215-266. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020186908707313 [ Links ]

19. Fouché L, editor. Mapungubwe: Ancient Bantu civilization on the Limpopo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1937. p. 21-22; plate XIII. [ Links ]

20. Beach DN. The Shona and Zimbabwe 900-1850. Gwelo: Mambo Press; 1980. [ Links ]

21. Tsheboeng AFP The archaeology of Majande and its environs [unpublished doctoral thesis]. London: University College London; 1998. [ Links ]

22. Caton-Thompson G. The Zimbabwe culture: Ruins and reactions. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1931. [ Links ]

23. Hemans HN. The history, the sociology, and the folklore and religion of the Abenanzwa Tribe. Proc Rhod Sci Ass. 1913;12:85-112. [ Links ]

24. Stayt HA. The Bavenda. London: Oxford University Press; 1931. [ Links ]

25. Van Warmelo NJ. Contributions towards Venda history, religion and tribal ritual. Pretoria: Government Printer; 1932. [ Links ]

26. Ralushai NMN. A Preliminary report on the oral history of Mapungubwe. Sibasa: South African Department of Environmental Affairs & Tourism; 2002. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Thomas Huffman

Email: Thomas.huffman@wits.ac.za

Received: 23 Jan. 2021

Revised: 13 May 2021

Accepted: 14 May 2021

Published: 29 July 2021

Editors: Margaret Avery

Funding: University of the Witwatersrand Research Incentive Scheme (HUFF013)