Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Science

versión On-line ISSN 1996-7489

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.117 no.5-6 Pretoria may./jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2021/10933

DISCUSSION DOCUMENT

POPIA Code of Conduct for Research

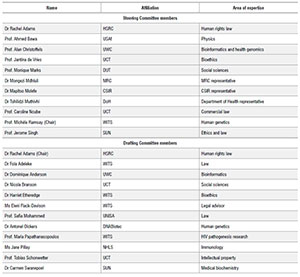

Rachel AdamsI; Fola AdelekeII; Dominique AndersonIII; Ahmed BawaIV; Nicola BransonV; Alan ChristoffelsIII; Jantina de VriesVI; Harriet EtheredgeVII, VIII; Eleni Flack-DavisonIX; Mark GaffleyX; Monique MarksXI; Mongezi MdhluliI; Safia MahomedXIII; Mapitso MolefeXIV; Tshilidzi MuthivhiXV; Caroline NcubeXVI; Antonel OlckersXVII; Maria PapathanasopoulosXVIII, XIX; Jane PillayXX; Tobias SchonwetterXXI; Jerome SinghXXII; Carmen SwanepoelXXIII; Michèle RamsayXXIV

IHuman Sciences Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa

IISchool of Law, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIISouth African National Bioinformatics Institute, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

IVUniversities South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

VSouthern African Labour Development Research Unit, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

VIDepartment of Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

VIIWits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIIISteve Biko Centre for Bioethics, School of Clinical Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IXResearch Office, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

XFaculty of Law, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

XIUrban Futures Centre, Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa

XIISouth African Medical Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

XIIICollege of Law, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

XIVCouncil for Scientific and Industrial Research, Pretoria, South Africa

XVNational Department of Health, Pretoria, South Africa

XVIDepartment of Commercial Law, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

XVIIDNABiotec, Pretoria, South Africa

XVIIIAssistant Dean: Research and Postgraduate Affairs, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

XIXDirector: HIV Pathogenesis Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

XXNational Health Laboratory Service, Johannesburg, South Africa

XXIDirector: Intellectual Property Unit, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

XXIICentre for Medical Ethics and Law, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

XXIIIDivision of Haematological Pathology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

XXIVDirector: Sydney Brenner Institute for Molecular Bioscience, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Keywords: data protection, protection of personal information, research participants, research ethics, open science

On 1 July 2021, the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA or the Act), No. 4 of 2013, will come into effect. The Act will have implications for all research activities that involve the collection, processing, and storage of personal information. POPIA provides for the development of Codes of Conduct to guide the interpretation of the Act with respect to a particular sector or class of information.1 Codes of Conduct are particularly important for providing for prior authorisations in terms of Section 57 of POPIA for the sector to which it applies. Prior authorisations are required for using unique identifiers of personal information in data processing activities, and for sharing special personal information or the personal information of children with countries outside of South Africa that do not have adequate data protection laws. In order to understand and functionally interpret the provisions of POPIA for the research community in the Republic of South Africa (South Africa), the Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf) is leading a process to develop a Code of Conduct (Code) for research under the Act. A Code can be developed by the Information Regulator or by a public or private body deemed 'sufficiently representative' of the bodies in respect of the particular class of information or sector to which the Code will apply. During 2020, ASSAf was approached by scientists in South Africa to consider the development of a Code for research, and public events were held during Open Access Week in October 2020, and Science Forum South Africa in December 2020, to further discuss the role of ASSAf in this regard. A Commentary published in this issue sets out the full rationale for the development of the Code by ASSAf and details the consultation process to date.2

Within the research setting, POPIA regulates the processing of personal information for research purposes, and the flow of data across South Africa's borders to ensure that any limitations on the right to privacy are justified and aimed at protecting other important rights and interests. The new regulatory system that POPIA establishes will function alongside other legislation and regulatory structures governing research in South Africa, as outlined below. The law which takes precedent will be that which provides the most comprehensive protections to the rights of individuals in South Africa.

This paper sets out the key discussion points in relation to the development of the Code. It is intended as a paper that can support further stakeholder consultation and public engagement in the process of developing a Code which meets the needs, and is representative of, the South African research community.

Background to POPIA

POPIA provides for the lawful processing of personal information in South Africa. It sets out the roles for various parties involved in the processing (including collection, use, transfer, matching and storage) of personal information. Briefly, these roles include but are not limited to:

• the 'Responsible Party', which - in this case - is the researcher (Principal Investigator) or research institution responsible for determining why and how the personal information is being processed;

• the 'Operator' - a third party contracted by the responsible party to process personal information on their behalf;

• an 'Information Officer' who is the designated individual within an institution responsible for ensuring compliance with POPIA; and

• the 'Data Subject' who is the person whose information is being processed and, in the case of research, would be the 'study/research participant'.

The Act outlines eight (8) conditions for the lawful processing of personal information, all of which must be fulfilled in order for such processing to be lawful. These conditions are:

1. Accountability: the responsible party must ensure that all the conditions for the lawful processing of personal information laid out in POPIA are complied with at the time of the determination of the purpose of processing and during processing (Section 8).

2. Process limitation: the responsible party must ensure there is a lawful basis for the processing of personal information; that such processing is necessary for a defined purpose and could not be achieved without processing such personal information; and that the information is collected directly from the data subject and with informed consent (Sections 9-12). The lawful basis must be determined at the outset of the processing and will have an effect on the rights of data subjects. The lawful bases outlined in POPIA are1:

POPIA Section 11 (1)

a. the data subject or a competent person where the data subject is a child consents to the processing;

b. processing is necessary to carry out actions for the conclusion or performance of a contract to which the data subject is party;

c. processing complies with an obligation imposed by law on the responsible party;

d. processing protects a legitimate interest of the data subject;

e. processing is necessary for the proper performance of a public law duty by a public body; or

f. processing is necessary for pursuing the legitimate interests of the responsible party or of a third party to whom the information is supplied.

It is important to note that because consent can be withdrawn at any time, it is not an ideal lawful basis for the processing of personal information for research purposes. In addition, there are circumstances where processing for research purposes can take place without the express consent of the data subject. Bodies which perform research functions would be advised to determine if their processing of personal information for research complies with a public law duty, such as would be the case with a research council founded through an act of Parliament, and/or whether their processing of personal information for research fulfils their legitimate interests. Further guidance in this regard will be provided under the Code.

3. Purpose specification: the collection and processing of personal information must be for a defined purpose; records should not be retained longer than is necessary and must be deleted or destroyed after the purpose for collection and processing has been fulfilled. The retention of records containing personal information is allowed for research purposes where there is a specifically defined need to retain such information and where further relevant safeguards are in place (Sections 13-14).

4. Further processing limitation: further processing of personal information is permitted where such information is used for research, and only research, purposes (Section 15).

5. Information quality: personal information collected and stored must be accurate, up to date, complete and not misleading (Section 16).

6. Openness: responsible parties must maintain a record of all processing of personal information. The data subject must be informed regarding: why the information was collected, who collected it and where it is being held, what rights the data subject has to access and delete/correct the data, and if the data will be transferred to a third party and/or internationally during the processing. It is not necessary to inform the data subject of the above if their information is being processed only for research purposes (Sections 17-18).

7. Security safeguards: responsible parties must ensure that personal information is kept secure to maintain confidentiality and integrity, and to prevent data breaches. Any security breaches must be reported to the Information Regulator (Sections 19-22).

8. Data subject participation: the responsible party must ensure that the data subject is informed of their right to access, correct and delete their personal information and of the manner in which to do so (Sections 23-25).1

POPIA provides for a general prohibition on the processing of special personal information. Special personal information includes information relating to the health, political persuasion, race or ethnic origin, or criminal behaviour of the data subject. There is a similar ban on the processing of personal information relating to a child. There are some exceptions to these bans, discussed below.

Existing regulatory framework

Research in South Africa is governed by a number of existing legal instruments and provisions. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa3 provides under the Bill of Rights that '[e]veryone has the right to bodily and psychological integrity, which includes the right not to be subjected to medical or scientific experiments without their informed consent'3. In addition, the National Health Act, No. 61 of 2003 requires all research projects that involve human participants to obtain the express consent of the individual involved and to 'be conducted in the prescribed manner'4. This prescribed manner relates to any regulations which further govern research, which include, particularly, the South African Department of Health's5 guidelines on 'Ethics in Health Research Principles, Processes and Structures' of 2015 (hereafter the DoH Guidelines). The DoH Guidelines pertain to 'research that involves living human participants'5 and require prospective and independent ethics review. While the DoH Guidelines apply to 'health research', this is broadly defined as all research which contributes to the knowledge of:

• biological, clinical, psychological, or social welfare matters including processes as regards humans;

• the causes and effects of, and responses to disease;

• effects of the environment on humans;

• methods to improve healthcare service delivery;

• new pharmaceuticals, medicines, interventions, and devices; and

• new technologies to improve health and health care.5

Accordingly, all research projects that involve human participants - including where any personal information is collected, processed, or stored - are required to undergo a prior ethics evaluation from a suitably constituted research ethics committee, preferably registered with the National Health Research Ethics Council.

In addition, best practice guidelines for open science are being promulgated globally and nationally, with research funding agencies including the National Research Foundation now requiring that research data be made publicly available. Open science seeks to promote the benefit and advancement of science for all and open access data would typically be de-identified as far as reasonably possible to prevent direct identification of a data subject. In this circumstance, the provisions of POPIA would not apply, as POPIA does not apply to de-identified information that cannot be reasonably re-identified. This is consistent with the objectives of POPIA, set out in the Preamble, which include that the Act is

consonant with the constitutional values of democracy and openness, the need for economic and social progress, within the framework of the information society, requires the removal of unnecessary impediments to the free flow of information, including personal information.1

However, it is important in the development of this Code to consider international standards, including both those relating to open science and data protection law in the African Union and European Union, as, too, is noted in the Preamble to POPIA.1 This is particularly important given how data protection laws worldwide provide for a provision of 'adequacy' when sharing data with institutions in other countries. This means that cross-border data sharing can only take place where the other jurisdiction has an adequate standard of data protection or a data access agreement in place to ensure adequate data protection.

Scope of the Code

The Code, as it is currently being considered, pertains to research conducted in South Africa, or conducted by a responsible party domiciled in South Africa, and which - as part of the research process - uses (collects, processes or stores) personal information as defined under POPIA. This includes personal information that is used directly, i.e. collected directly from the data subject/research participant or that is used in the process of the research, e.g. research that uses a database which includes personal information.

As such, this Code is relevant to research - whether basic or applied - in any discipline including, but not limited to, natural sciences, engineering and technology, medical and health sciences, social sciences, education, management, economics, theology, law, and the humanities and which:

• follows a recognised scientific methodology or system of analysis, and improves or creates new knowledge, or deepens understanding; and

• would ordinarily undergo prior independent ethics review.

In this regard, this Code applies to both industry and academia and broadly takes research to mean the generation, preservation, augmentation, and improvement of knowledge by means of investigations and methods pertinent to the scientific or disciplinary field6-8, and which is mindful of the value of knowledge for the betterment of society, including open science.

The proposed Code pertains to research that uses personal information undertaken as part of experimental development research9, public health surveillance, statistical data collection on the part of state organs, and clinical trials, where such research is intended to be published in contribution to the respective field of knowledge.

The proposed Code will not apply to the following research or research-related activities: market research, political and public opinion polling, audits, quality assurance or programmatic monitoring and evaluation; or other research where the purpose is not directly to contribute to the improvement of knowledge through peer-reviewed publication.

Exclusions, exemptions and exceptions for research under POPIA

POPIA contains exclusions, exemptions and exceptions, some of which pertain to the processing of personal information for research purposes. The South African Law Reform Commission's report on 'Privacy and Data Protection', on which the drafting of POPIA was based, explains that exceptions 'map out the extent of the obligations under the rule -or principle', 'exemptions involves lifting a burdensome obligation from a responsible party while the burden continues to apply to others', and exclusions are 'where certain classes of responsible parties are excluded completely from the coverage of the law'.10

While emphasis here will be on outlining research-specific exceptions, it is important to not lose sight of the fact that some processing activities linked to research may also benefit from general or research-specific exclusions and exemptions in the Act.

Exclusions

In respect of research activities, the most pertinent exclusion relates to the processing of 'de-identified' information. This is defined as1:

"de-identify", in relation to personal information of a data subject, means to delete any information that-

(a) identifies the data subject;

(b) can be used or manipulated by a reasonably foreseeable method to identify the data subject; or

(c) can be linked by a reasonably foreseeable method to other information that identifies the data subject.

In practice, however, it is not always possible to completely de-identify data and there are certain categories of information which may not be de-identifiable, including genetic information (see section below on Genetic Data). In addition, re-identification can occur through matching or linking data sets. Under the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union (GDPR), the term 'pseudo-anonymisation' has been used to describe information that can be re-identified. The process of pseudo-anonymisation under the GDPR is described as:

the processing of personal data in such a manner that the personal data can no longer be attributed to a specific data subject without the use of additional information provided, that such additional information is kept separately and is subject to technical and organisational measures to ensure that the personal data are not attributed to an identified or identifiable natural person."

In addition, there are certain categories of information which may not be entirely de-identifiable, or may be identifying (that is, with the relevant technical and scientific understanding and resources, identifying information is information that immediately identifies an individual, such as a picture of a face), but not identifiable (not able to be identified).

Exemptions

Section 36 of POPIA1 stipulates that the processing of personal information ultimately does not violate a condition for the lawful processing of personal information under POPIA if the Regulator grants, on a case-to-case basis, an exemption under Section 37 of POPIA, or if the processing of personal information is carried out in accordance with Section 38 of POPIA and is necessary for the fulfilment of a function of a public body.

The Regulator may grant an exemption under Section 37 if the Regulator believes that the processing activities are in the public interest, or in the interest of either the data subject or a third party, provided these interests substantially outweigh the interference with privacy. Notably, according to Section 37 (2), the public interest includes historical, statistical or research activity, as well as processing toward 'the prevention, detection and prosecution of offences'1.

Exceptions

In addition to the exclusions and exemptions addressed above, POPIA also expressly provides that some of the POPIA conditions for processing personal information (part A) and restrictions for processing of special personal information (part B) as well as personal information of children (part C) do not (fully) apply in the context of research. These research-specific exceptions are captured in Table 1.

Consent

POPIA defines consent as any voluntary, specific and informed expression of will in terms of which permission is given for the processing of personal information. While POPIA emphasises the importance of consent being specific, it also recognises the importance of fostering research, and particularly research that is in the public interest (Section 37). In South Africa, research that involves human participants typically requires informed consent in terms of the National Health Act and the Constitution, and should seek prior clearance from a health research ethics committee or, in the case of a non-health discipline, another suitably constituted research ethics committee.

The DoH Guidelines endorse several forms of consent for use in health research in South Africa; these forms of consent are listed in Table 2.

It is clear that with the promulgation of POPIA, and in line with the definitions in the DoH Guidelines, a consent model for research where the data subject consented to the use of their data in future for absolute unknowns, such as in blanket consent (which is notably not endorsed by the DoH), would not be permissible. Instead, researchers will need to be as specific as possible in describing how the personal information from a data subject/research participant would be used in future.

POPIA envisages circumstances where the re-use of data by the same (or a different) responsible party would occur. This is outlined in condition four of the lawful processing of personal information on 'further processing limitations', provided under Section 15 of the Act. Further processing of personal information - which in the research community is understood as the re-use of data - is allowed for research where such processing is solely for research purposes and where the information will not be published in an identifiable form (Section 15 (3) (e)). Further processing is also permissible where the data subject has consented to such further processing, or where the information is already in the public domain. In addition, and as noted in Table 1, POPIA states that further processing for research purposes is permitted if: processing is necessary to 'prevent or mitigate a serious and imminent threat to' public health or public safety or where the processing is necessary to prevent or mitigate a serious threat to 'the life or health of the data subject or another individual'.1

In short, further processing is allowed where it is: for research purposes and where the information is not published in an identifiable form (note here the discussion on de-identification below); or where there is consent from the data subject to do so. Therefore, 'broad consent' - as defined under the DoH 2015 Guidelines - is permissible under POPIA if these conditions are fulfilled.

All three of the consent options endorsed for use in health research in South Africa are actively used in the country and would be permissible under POPIA where data subject rights are protected and the responsible parties are as specific as possible in detailing the future use of personal information at the time of consent, including any possible sharing with another responsible party. The important question for implementation of POPIA in research is therefore not whether different consent models ought to be used, but how they can be used in ways that minimise the risk of harm to the data subject as a result of a loss of privacy. The common conditions that are currently in place in research projects that seek consent for future use, generate a governance framework which seeks to ensure that the re-use of samples and data are ethical. This 'governance framework' includes all the arrangements that determine the re-use of data and samples for future use, and includes: the strength of ethics regulatory oversight; the presence and effective functioning of data use and oversight, for instance, data access committees; community engagement; and mechanisms of data protection which are to prevent unauthorised access to data.

To ensure compliance with POPIA in relation to consent, responsible parties should assess, through an initial risk assessment conducted prior to ethics approval and documented in the data management plan, the balance between the risk of harm resulting from a loss of privacy

to the data subject, the strength of the governance framework that regulates the re-use of data, the potential utility of data for future use, and the model of consent adopted. Where the risk to privacy is higher, greater safeguards should be put in place to mitigate against potential harms. Where a research project is determined 'high risk', a full privacy impact assessment should be conducted to determine where further safeguards may be necessary to protect personal information and mitigate against any potential harm to the data subject. See section below on 'High-risk information and risk assessments' in relation to high-risk research.

Data sharing and re-use under POPIA

In addition to the issue of consent discussed above, data sharing and data re-use invokes two notions under POPIA:

1. the use of personal information not collected directly from the data subject, where personal information is shared outside of the original responsible party; and

2. where the information is shared with a body outside South Africa, the sharing of data by a responsible party to a foreign third party.

Under Section 12, POPIA provides that personal information should be collected directly from the data subject. However, POPIA also allows for circumstances where data are not collected directly from the data subject if the data subject has consented (Section 12 (2) (b)), or if the personal information is already in the public domain (Section 12 (2) (a)), or where it is 'not reasonably practicable' (Section 12 (2) (f)). In addition, Section 18 (4) (f) (ii) provides that notification to the data subject when processing their personal information is not necessary when the information is being processed for research. In order to invoke Section 12 (2) (f), the burden of proof would be on the responsible party to show why it was not reasonably practicable to obtain the data directly from the data subject, and this would need to be documented in a risk assessment, outlined above, recorded in the data management plan. This may include assessing what resources were or were not available to the researchers to obtain the data directly from the data subject and the number of data subjects involved.

In addition, in accordance with the principle of data minimality set out in POPIA, data sharing should be encouraged between trusted responsible parties using the data for similar research-based purposes, over the collection of a new batch of personal information from a new set of data subjects.

Consent for processing personal information of a child

Where consent of a child is required for processing personal information, Section 11 of the Act provides that a competent person must provide consent on their behalf. The person consenting must be legally competent to consent to the action or decision of the child. The Act does not, however, distinguish between children of different ages and therefore between different levels of competency and autonomy with respect to the rights of the child.

POPIA prohibits the processing of personal information concerning a child. Exceptions include, amongst other things, where processing has been carried out with the prior consent of a competent person (or where deliberately disclosed by the child with the consent of a competent person). Additionally, processing is permitted for research purposes that serve a public interest and the processing is necessary, or where it would be impossible, or require a disproportionate effort, to obtain consent. Here guarantees must be put in place to show that processing does not adversely affect the privacy of the child.

The DoH Guidelines5 provide detailed insight into how child consent should be construed which go beyond what is provided under POPIA. Importantly, it is for the child, when of an age to consciously do so, to make the decision to consent and the parent (or competent person) to provide permission. Paramount is that the best interests of the child be considered and upheld. Some additional considerations include whether consent should be re-obtained when the child reaches 18 years, reflecting the child's evolving maturity and capacity to give consent. In addition, there are certain matters where, for reasons of sensitivity, it may be desirable and ethically justifiable for minors to consent independently of a competent person. This is particularly important for research where children may not be willing to participate if their parents must know about the nature of the research in order for permission to be obtained. Finally, appropriate risk standards similar to those used in the DoH Guidelines should be developed for POPIA.5

Information and samples

Information as a standalone term is not defined within POPIA. However, personal information under the Act means information relating to an identifiable, living, natural person, and where it is applicable, an identifiable, existing juristic person.

For research purposes under POPIA, this implies that a human biological sample by itself - that is not inherently identifiable and which is collected during the research process - does not fall under POPIA's definition of personal information. [Note, however, that the European Data Protection Board has recently prescribed that genetic data be treated as personal data under the GDPR.12(para.51)] Human biological samples would therefore fall under the scope of the National Health Act 2003, its Regulations and DoH Guidelines. When information is derived from the sample that is identifiable and relates to a living natural person, that specific information would then be considered personal information and fall under the remit of POPIA. However, the fact that certain biological samples (for example, a fingerprint) are innately identifiable can cause confusion around the exact point at which these samples become personal information due to their potential identifiability. In addition, further concerns may arise regarding the point at which these samples and their associated data may become identifiable, through the sharing of anonymised samples across different sectors. The question around whether potentially identifiable samples constitute personal information is debatable. Yet, POPIA is clear that the personal information must relate to an identifiable, living, natural person. Without any national case law providing clarity and the provisions of the Act open to interpretation, uncertainty and ambiguity remain problematic regarding the exact point at which biological samples become personal information as contemplated under the Act. For the purposes of the Code, human biological samples themselves should fall outside the remit of POPIA until identifiable information relating to a natural living person is derived from the sample.

Genetic data

Genetic and biometric data are not separately defined under POPIA. Genetic data are understood as personal information relating to the genetic characteristics (inherited or acquired, e.g. through mutations in cancer cells) of a person that provides unique information about that person. In cases where genetic 'uniqueness' can be considered biometric data, these data would require a lawful basis for processing, subject to POPIA regulations.

In the case of genetic information, literature has demonstrated the ability to identify an individual from a data subset that relied on linkage to other identifiers such as matching the genetic data against a reference sample, connecting genetic data to non-genetic databases, or generating a profile from genetic data (e.g. ethnicity, eye colour, skin colour) and cross-referencing this with another data set. It should be noted, however, that the risk of identifying an individual through genetic data is highly dependent on the availability of additional identifiers. Several additional challenges therefore arise for the use of genetic data in the context of POPIA and the processing of personal information.

Technologies that generate genetic information are rapidly advancing and the associated costs for generating such data are decreasing, making research which generates and processes genetic data more accessible and affordable. There is substantial and translational benefit to genetic/genomic approaches in research and health, heralding new understanding of disease epidemiology, diagnostics and therapeutics. Going forward, it is essential to ensure that no one is left behind in the genomic revolution and that all can benefit from research that could lead to beneficial innovations such as personalised medicine. For this vision to be actualised, it is imperative that the genomic data that are publicly available are also representative of all people.13 This means, at least in part, that South African data should continue to be made available both nationally and internationally for analysis and re-use for the advancement of science. This is in line with established standards in open science and genomics research that include many journals and funders requiring research data sets to be made available and researchers sharing their data in the spirit of open research and collaboration.14

As indicated above, there is tension in the interpretation of genetic data, namely that whilst even limited genetic information from an individual can be highly identifying, this does not necessarily mean that an individual is identifiable through their genetic data. To identify a person on the basis of genetic information requires linking other information that identifies the person, to their genetic data, as is the case with biometric information, such as fingerprint data: whilst a fingerprint is unique to each person, a fingerprint alone is unlikely to identify the person amongst all other people; some other record needs to exist that links the fingerprint to a person's name before the fingerprint can be used as a source of identification of the person.

Risks to data privacy related to personal information lie in the potential for re-identification and in potential discrimination through the use of genetic data (e.g. racial profiling). For these reasons, genetic data need to be subjected to a higher level of privacy protection when compared to traditional health information. Under Section 32 (5) of POPIA, processing of health information concerning inherited characteristics is permitted if a serious medical interest prevails, or the processing is necessary for historical, statistical or research activity.

The purpose of the processing of genetic data and its future use are important in the context of assessment by ethics committees. De-identification or pseudo-anonymisation of genetic data, as well as appropriate consent approaches, need to be clarified and would require more consideration. It is important that community engagement and individual engagement processes precede informed consent to explain the risks and how they would be mitigated. It may also be useful to consider the addition of a right not to have one's personal data de-identified, as once de-identified, the individual to which the personal information originally related has no rights over that information, such as a right to access or delete it. In which case, it may be prudent to include de-identification of personal information as an express item a data subject must provide consent for.

Additional safeguards which would be relevant to genomic research include provision of detailed information related to data access and use, by the researchers, and the informed consent process for the participant should specifically refer to any potential data sharing (nationally and internationally). A risk assessment should be conducted by the responsible party to determine the likelihood that an individual could be re-identified, and such assessments should be included in ethics review processes. Confidentiality certificates with consent to limit access could also be considered.

High-risk information and risk assessments

POPIA requires that Codes of Conduct provide specific provisions for the processing of personal information considered 'high risk' within the context and scope of the Code.15 In this context, we take 'risk' here to mean a risk to the rights of the data subject, including but not limited to the right to privacy, as a result of that person's personal information not being adequately protected. Such risks - which often overlap in reality - include:

• Individual identification:

o risk of loss of privacy; and

o risk of unconsented identification,

• Stigmatisation: risk of individual stigma (group/community belonging);

• Discrimination and bias;

• Trauma: risk to mental well-being and health (particularly acute for children, vulnerable and marginalised people); and

• Legal prosecution.

Examples of personal information that could be considered high risk include: health data, particularly HIV status; hereditary diseases or other information that could lead to individual stigma; children's information, and information of other vulnerable and marginalised individuals; and behavioural information in relation to a crime, or behaviour deemed deviant or non-normative.

At the outset of a research study, the responsible party/parties must conduct a risk assessment, as noted above. In addition to assessing how high risk the types of personal information being processed are, the risk assessment should also take into account: whether personal information will be transferred outside of South Africa and the extent of the data protection regulations in the country where the personal data will be received; whether unique identifiers will be processed as part of an information matching programme (see below); and whether any operators will be contracted to perform any processing on behalf of the responsible party and what risks such operators may pose (this could include assessing whether the operator has a POPIA compliance policy, or has recently had any data breaches). The risk assessment should be documented under the data management plan, together with the lawful basis for the processing of personal information, and details of the accountable party in terms of POPIA (particularly in the case of a research consortium where there may be more than one responsible party). Where a study is deemed high risk, a full privacy impact assessment should be carried out and vetted by the Information Officer of the research institution(s), as per Section 4 (1) (b) of the POPIA Regulations (No. R. 1383, 14 December 2018).

The processing of high-risk information, as outlined above, requires further safeguards to be in place to balance the potential harms caused by disclosure or breach of confidentiality with the benefits to the improvement of knowledge through research. Additional safeguards provided under POPIA include: data minimisation (ensuring that only the personal information that is essential for testing the research hypothesis or answering the research question is collected), anonymisation of data and data security.

Table 3 sets out the types of information listed under POPIA and their potential risks.

Information matching programmes

POPIA requires Codes of Conduct to develop provisions for how personal information rights will be protected where information matching programmes are in use. POPIA defines information matching programmes (IMP) as:

"information matching programme" means the comparison, whether manually or by means of any electronic or other device, of any document that contains personal information about ten or more data subjects with one or more documents that contain personal information of ten or more data subjects, for the purpose of producing or verifying information that may be used for the purpose of taking any action in regard to an identifiable data subject.1

Information matching, for example through two or more spreadsheets, using code/macros to link sources via an identifier, can be achieved in several ways: (1) non-algorithmic means such as the comparison or combination of data across multiple data sources, or (2) algorithms. When using algorithmic means, information matching can be generally, but not exclusively, performed via machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI).

There are numerous ways in which data sources can be linked, of which a non-exhaustive list of examples is shown below across different data dimensions:

1. Individual identifiers: identity numbers, tax reference numbers, phone numbers.

2. Geographic identifiers: country, town, village, metro.

3. Activity identifiers: employment, hobbies, social media, church, political party membership.

Although many of these data points/sources are in the public domain, triangulation across data sources and data dimensions can allow identification of the data subject. Oftentimes, the matched data are informative for research and also cost effective from a research perspective. It is important to note that information matching for cost-effective purposes may be an important enabler for the research community to minimise the amount of personal data that is collected, sometimes from over-researched communities, in order to comply with the principle of data minimisation.

The challenge in using such matched data in research is ensuring that the data subject's rights are upheld. Research ethics committees play an important role here in ensuring the rights of data subjects are protected during such research activities. However, it would also be required that data subjects provided consent, at the time of collection, to their data being potentially matched with a data set of another responsible party, if not matching data with a data set that is already in the public domain. Where this activity is for research purposes, this is permissible in terms of POPIA.

In other jurisdictions, data protection oversight and regulatory bodies have considered how to protect data subject rights in relation to the use of IMPs, and particularly AI and machine learning based data systems.16 Some notable points include that the responsible party must implement measures to prevent arbitrary discrimination of an individual. The AI model must therefore be trained with appropriate data, and, where possible, should not prioritise high-risk information, such as related to racial/ethnic origin or political opinion, which may lead to discrimination. Research ethics committees should - in cases where these data are required to answer a specific research question in order to not erode the quality of the IMP - evaluate the data used for this purpose in the context of a risk-based-consent model, as above.

It might be important to set requirements for responsible parties to outline how data are being selected, as well as to provide an outline of how the algorithm was or would be developed and tested. In this case, if a previously developed IMP will be used in the research, this information should be conveyed to the data subject during the informed consent process.

However, if the purpose of the data collection from the data subject is to develop a new IMP this information will not yet be available, and a general IMP development scenario should be explained to the data subject.

It would also be key to ensure that the purpose for processing personal information in AI systems is clearly established, and indicated, when the data are collected. The purpose of the processing must be fully explained to the data subject such that they can make an informed choice regarding whether to provide consent, given that the responsible party will know the overall processing purpose in the research context, but perhaps not yet the underlying sub-processing purposes that may be revealed during the research study.

In the context of AI, it may be difficult to explain how information is connected within a specific process embedded in a 'black box' or algorithm. A similar challenge is encountered in genomic research where complex concepts have to be conveyed in lay terms to data subjects. Transparent processing requires that processing information be clarified with the data subject during the informed consent process.

The subset of conditions for lawful processing of personal information outlined in POPIA and addressed above, requires the consideration of overarching principles for matching data. These include: ensuring the confidentiality and integrity of personal information through security measures and safeguards, minimising the risk of re-identification of de-identified data; data minimisation; transparency in the processing of personal information; documenting and conveying the purpose specification; and notifying data subjects such that they know where, and by whom, their data are held, and can access and claim their data rights.

Software design should also consider privacy by design principles.17 Privacy protection can be built into systems as far as possible and ensure data protection is safeguarded in the default settings.

In addition, risk assessment and management plans could be included in the review process for research approval by the research ethics committees where IMPs are being utilised. Risk assessments should evaluate the reasonable likelihood of data subject identification or re-identification with respect to objective factors such as skill required, technology available, and time/cost required. The risks associated with using an algorithm and the impact on the data subject should be recognised and articulated to the data subject during the consent process. In cases where impact assessments have identified categories of data with higher levels of risk, more stringent safeguards must be put in place, where there are the resources to do so.

Security safeguards

Under POPIA, Condition 7 of the lawful processing of personal information requires responsible parties to ensure that personal information collected by the responsible party is kept secure at all times - through appropriate, reasonable, organisational and technical measures - to protect against security breaches.

In order to determine which measures are the most appropriate and reasonable, an organisational risk analysis and privacy impact assessments must first be performed, prior to evaluation of processes to manage and mitigate the risks of a data breach. There are several accepted frameworks for IT security practices and procedures, with the ISO27000 series being the most widely accepted Information Security management standard.18-20 The US National Institute of Standards and Technology cyber security framework has also been recognised as an important standard for organisations.

Information technology security strategies prevent unauthorised access to data assets of an organisation, to maintain the integrity and confidentiality of sensitive information. It is important to note that these strategies do not solely rely on the hardware and software mechanisms, but include additional security measures such as appropriate policies, procedures, and physical controls. At an organisational level, specific

IT policies may be in place and would form part of the 'appropriate, reasonable, organisational and technical measures' stipulated by POPIA.

The use of security measures to protect personal information differs from one research body to another, depending on both organisational requirements and available resources.21 Examples of data security measures are included in Table 4.

Social media data

POPIA provides that when information is in the public domain it can be used and processed without consent. This would include publicly available personal information on social media platforms, as well as blogs and websites that are open to the public. A useful report in this regard is 'Ethical Guidelines on Social Media' published by the Health Professions Council of South Africa.22 This is particularly pertinent in South Africa where there is no specific legislation regulating social media.23

As consent is not necessary for the processing of personal information from public sources, the lawful basis under POPIA for such processing will not be consent. Unless the researchers were conducting research mandated by a public law, the lawful basis that would be relied on to process publicly available personal information would be the legitimate interest of the responsible party.

A data subject's expectation of privacy when using social media platforms is inversely proportional to the rigour of privacy settings associated with the platform upon which information is shared. Hence, when sharing information on an account that has no privacy settings, and is thus publicly available, the data subject has - in effect - forfeited their right to privacy. When sharing information on an account that has activated certain privacy settings, but where that information can be viewed by millions of people (for instance a platform hosted by a public figure or institution), a data subject has a lower expectation of privacy than when sharing information to a platform that can be seen only by a select few. When information is shared with only one other individual, such as on a WhatsApp messenger, the data subject has a high expectation of privacy. The level of POPIA-related safeguards for research applications in social media must be commensurate with the expectation of privacy implied by the data subject when they posted their personal information.

In this case there are three instances of how the data subjects' information could be used for research purposes: (1) the information can be de-identified and thus falls outside the scope of POPIA; (2) where the information is not de-identified; and (3) where the data cannot be de-identified. While the expectation of privacy is diminished, cases involving minors and other vulnerable groups5 need to be considered in order to ensure their rights are protected and that they are not subject to any harm as a result of the publicly available information.

In addition, the Information Regulator recently released a comment in relation to changes to the terms and conditions of WhatsApp, a Facebook company. The Information Regulator stated that in terms of Section 57 of POPIA, the social media platform may not

process any contact information of its users for a purpose other than the one for which the number was specifically intended at collection, with the aim of linking that information jointly with information processed by other Facebook companies

unless it obtains prior authorisation from the Information Regulator to do so. Hence, the intent of the data subject is a significant factor in how the data of the data subject may be dealt with, although in cases involving international platform providers it poses cross-jurisdictional challenges.24

Overall, social media data should be de-identified as early as possible in the research process and the principle is to only collect information that is directly relevant to the research. The de-identification process must also include a de-coupling process in which, for example, location and other data that are not relevant to the research hypothesis are disconnected from the data relevant to the research and (1) are not collected by the researcher, or (b) are disconnected from the post prior to processing it for research purposes. It is recommended that the specific requirements for this process should be processed and approved by the relevant research ethics committee.

Cross-border data sharing/information flows

Section 72 of POPIA sets out the conditions for transferring personal information to a foreign jurisdiction. In principle, responsible parties must ensure that the foreign country with which personal information is being shared or transferred to has as high a level of data protection as offered under POPIA. Responsible parties must also ensure that a transfer agreement is in place, which offers the necessary safeguards and protections for transferring personal information. Transfer agreements must be in binding contractual form. This broadly echoes the requirements of the GDPR in relation to cross-border data sharing. In July 2020, the Court of Justice of the European Union decision held that the EU-US Privacy Shield is no longer a valid basis for transferring EU personal information to the USA.25 The decision, known as Schrems II, found that the European Commission's adequacy determination for the EU-US Privacy Shield Framework is invalid due to concerns regarding the necessity and proportionality of the surveillance activities of the US government and the availability of actionable judicial redress for EU data subjects. Second, the decision affirmed the validity of standard contractual clauses, while stating that data exporters and importers must verify, on a case-by-case basis, whether the law in the recipient country ensures adequate protection, similar to what is offered under the GDPR.25,26 Where no adequate protection is in place (such as where the foreign country to which data are being transferred does not have a functional data protection regulatory system in place), additional safeguards must be provided by the data exporters and importers to guarantee such protection, and built into the transfer agreement. In effect, Schrems II made this incumbent on 'data controllers' (what would be 'responsible parties' under POPIA) to ensure not only that other countries with which personal information is shared have a similar level of data protection regulation, but also that safeguards are in place to protect the personal information and rights of the data subject.

Parties to a transfer can offer enhanced legal guarantees that build on those in standard contractual clauses but provide stricter conditions for suspending data flows and deleting data in cases of unauthorised government access. Second, technical measures such as strong encryption methods, as well as organisational measures such as commitments to suspend data transfers to countries that do not respect the rule of law, based on internationally recognised standards, could be adopted. It is the responsibility of the responsible party to ensure that sufficient legal protections are in place when transferring personal information outside of South Africa, and it is encouraged that responsible parties sharing information outside of South Africa take note of the obligations around cross-border data transfer set out by the GDPR and the Schrems II decision.

Section 72 of POPIA provides that data can also be shared with a foreign country where the data subject consents to the transfer, or where the transfer would be to the benefit of the data subject, or is necessary for the performance of a contract between the responsible party and the data subject. However, Section 57 (1) (d), indicates that if special personal information, or the personal information of a minor, is to be transferred to a country that does not provide an adequate level of protection under Section 72, then prior authorisation of the Information Regulator is required. Section 57 (3) states that this prior authorisation will not be needed if a Code has come into force for a specific sector. Thus, the Code for Research will need to include provisions to guide researchers in transferring or sharing personal information outside of South Africa, and will need to take into account the developing international best practice in this regard, in order to ensure that South African researchers remain internationally competitive.

Governance of the Code of Conduct

It is recommended by the Information Regulator that the body which develops the Code for Conduct takes responsibility for governing the Code, on the basis that the body has been deemed representative enough of the sector to which the Code will apply.27 There are two key duties in respect to the governance of the Code, which will fall on ASSAf. First, to report on the sector's compliance with the Code to the Information Regulator on an annual basis. This will include receiving annual statistics from all bodies that fall under the Code with respect to the number and nature of complaints received in relation to the Code.27

The second will be for ASSAf to handle complaints in relation to the Code. Given that the scope of research activities that fall under this Code would ordinarily have undergone prior ethics approval, ASSAf would not be the first port of call for handling complaints. Instead, what is being considered is a tiered process whereby a complainant would first approach the relevant research ethics committee which had authorised the research. If the complainant is, at this stage, aggrieved by the outcome decided by the research ethics committee, the complainant would then approach the National Health Research Ethics Council if the research ethics committee in question is registered with the National Health Research Ethics Council, as provided for under the National Health Act. If a complaint in relation to the Code was in relation to a research project that had not undergone ethics clearance, then the complaint could be brought directly to ASSAf. However, as ethics review will constitute a key safeguard for ensuring compliance with POPIA and the Code, the complaint against the responsible parties would not be reviewed favourably. At this point, if the matter was still not resolved and related squarely to a violation of this Code, it would be handled by an independent committee established by ASSAf, and in accordance with the guidance on POPIA complaints handling as published by the Information Regulator.28 The last port of call for complaints, following handling by ASSAf's independent committee, would thereafter be the Information Regulator.

Conclusion

This document has sought to outline the main areas relating to the processing of personal information for research purposes which the Code will address, including: what consent models would be permissible under POPIA; the issues in relation to genetic research and the processing of personal information contained in inherited characteristics; the use of IMPs by researchers; and the use of personal information obtained from social media platforms for research. This is not an exhaustive list of the concerns faced by the research community in respect of the changes that POPIA will bring about. Other issues which the Code will address relate to intellectual property law, including but not limited to patents, as well as the commercialisation of research data. However, with ongoing and wide consultation with the scientific community in South Africa and all relevant stakeholders, it is hoped that the Code will provide guidance in supporting the lawful and responsible use of personal information while conducting scientific research in South Africa.

Acknowledgements

We thank all those who have contributed to this Discussion Document from various sectors and disciplines. We are particularly grateful to three anonymous readers for their input.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

Authors' information

The authors, excluding Mark Gaffley who is working as a research assistant on this project, are all members of either the ASSAf-appointed POPIA Code of Conduct Steering Committee or Drafting Committee.

References

1. Protection of Personal Information Act 4 of 2013, Republic of South Africa. [ Links ]

2. Adams R, Veldsman S, Ramsay M, Soodyall H. Drafting a Code of Conduct for Research under the Protection of Personal Information Act No. 4 of 2013. S Afr J Sci. 2021;117(5/6), Art. #10935. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2021/10935 [ Links ]

3. Human Sciences Research Council Act 17 of 2008, Republic of South Africa. [ Links ]

4. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 108 of 1996, Republic of South Africa. [ Links ]

5. National Health Act 61 of 2003, Republic of South Africa. Available from: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a61-03.pdf [ Links ]

6. South African Department of Health (DoH). Ethics in health research: Principles, processes and structures. 2nd ed. Pretoria: DoH; 2015. Available from: https://www.sun.ac.za/english/research-innovation/Research-Development/Documents/Integrity%20and%20Ethics/DoH%202015%20Ethics%20 in%20Health%20Research%20-%20Principles,%20Processes%20and%20 Structures%202nd%20Ed.pdf [ Links ]

7. South African Medical Research Council Act 58 of 1991, Republic of South Africa. [ Links ]

8. Agricultural Research Act 86 of 1990, Republic of South Africa. [ Links ]

9. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OCED). Frascati Manual 2015: Guidelines for collecting and reporting data on research and experimental development, the measurement of scientific, technological and innovation activities. Paris: OECD; 2015. [ Links ]

10. South African Law Reform Commission (SALRC). Project 124: Privacy and data protection report. Pretoria: SALRC; 2009. para 4.4.3. [ Links ]

11. General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679, European Union. [ Links ]

12. European Data Protection Board (EDPB). EDPB Document on response to the request from the European Commission for clarifications on the consistent application of the GDPR, focusing on health research [document on the Internet]. Available from: https://edpb.europa.eu/sites/edpb/files/files/file1/edpb_replyec_questionnaireresearch_final.pdf [ Links ]

13. Popejoy AB, Fullerton SM. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature. 2016;538:161-164. https://doi.org/10.1038/538161a [ Links ]

14. Powell K. The broken promise that undermines human genome research. Nature. 2021;590:198-201. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-00331-5 [ Links ]

15. Information Regulator of South Africa - Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (DoJ). Re: Notice relating to consultations on guidelines to develop codes of conduct in terms of chapter 7 of the Protection of Personal Information Act of 2013 on the 6th November 2019. Johannesburg: DoJ; 2019. para 7.11. [ Links ]

16. The Norwegian Data Protection Authority (Datatilsynet). Artificial intelligence and privacy: Report, January 2018. Oslo: Datatilsynet; 2018. [ Links ]

17. The Norwegian Data Protection Authority (Datatilsynet). Software development with data protection by design and by default. Oslo: Datatilsynet; 2017. Available from: https://www.datatilsynet.no/en/about-privacy/virksomhetenes-plikter/innebygd-personvern/data-protection-by-design-and-by-default/?print=true [ Links ]

18. National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce (NIST). Cybersecurity framework. Gaithersburg, MD: NIST; 2016. Available from: https://www.nist.gov/industry-impacts/cybersecurity-framework [ Links ]

19. Crook G. The implications of IT governance outlined in King IVTM. Durban: BDO; 2016. Available from: https://www.bdo.co.za/en-za/insights/2016/report/the-implications-of-it-governance-outlined-in-king-iv [ Links ]

20. Lewinson M. PRINCE2 methodology overview: History, definition & meaning, benefits, certification [webpage on the Internet]. c2011 [cited 2021 Apr 26]. Available from: https://mymanagementguide.com/prince2-methodology-overview-history-definition-meaning-benefits-certification/ [ Links ]

21. Abiodun OP. Exploring the influence of organizational, environmental, and technological factors on information security policies and compliance at South African higher education institutions: Implications for biomedical research [thesis]. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape; 2020. https://etd.uwc.ac.za/handle/11394/8074 [ Links ]

22. Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA). Ethical guidelines for good practice in the health care professions: Ethical guidelines on social media: Booklet 16. Pretoria: HPCSA; 2019. Available from: https://www.hpcsa.co.za/Uploads/Professional_Practice/Conduct%20%26%20Ethics/Ethical2%2 0Guidelines%20on%20Social%20Media.pdf [ Links ]

23. South African Department of Government Communications and Information Systems (GCIS). Social media policy guidelines: April 2011. Pretoria: GCIS; 2011. Available from: https://www.gcis.gov.za/sites/default/flles/docs/resourcecentre/guidelines/social_media_g uidelines_flnal_20_april2011.pdf [ Links ]

24. Information Regulator of South Africa, Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (DoJ). Media statement: Information Regulator SA provides legal analysis on WhatsApp privacy policy. Johannesburg: DoJ; 2021. Available from: https://www.justice.gov.za/inforeg/docs/ms-20210303-Whatsapp.pdf [ Links ]

25. Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). The Court of Justice invalidates Decision 2016/1250 on the adequacy of the protection provided by the EU-US Data Protection Shield. Luxembourg: CJEU; 2016. Available from: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-07/cp200091en.pdf [ Links ]

26. European Data Protection Board (EDPB). Frequently asked questions on the judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union in Case C-311/18 - Data Protection Commissioner v Facebook Ireland Ltd and Maximillian Schrems [webpage on the Internet]. c2020 [cited 2021 Apr 13]. Available from: https://edpb.europa.eu/our-work-tools/our-documents/ohrajn/frequently-asked-questions-judgment-court-justice-european-union_en [ Links ]

27. Information Regulator of South Africa, Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (DoJ). Guidelines to develop codes of conduct: Issued under the Protection of Personal Information Act 4 of 2013 (POPIA). Johannesburg: DoJ; 2021. Available from: https://www.justice.gov.za/inforeg/docs/InfoRegSA-Guidelines-DevelopCodeOfConduct-22Feb2021.pdf [ Links ]

28. Information Regulator of South Africa, Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (DoJ). Standard for making and dealing with complaints in a code of conduct (prescribed in terms of Section 65 of the Protection of Personal Information Act No 4 of 2013). Johannesburg: DoJ; 2021. Available from: https://www.justice.gov.za/inforeg/docs/InfoRegSA-Standard-CodeOfConduct-Complaints-20210301.pdf [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Rachel Adams

Responsible Party', which - in this case - is the researcher (Principal Investigator) or research

Email: radams@hsrc.ac.za

Published: 03 May 2021