Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Science

On-line version ISSN 1996-7489

Print version ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.117 n.1-2 Pretoria Jan./Feb. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2021/7807

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Constraints on improving higher education teaching and learning through funding

Temwa MoyoI; Sioux McKennaII

ICentre for Higher Education Research, Teaching and Learning, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa

IICentre for Postgraduate Studies, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In the midst of massification, targeted funding has been used in various countries to address inefficiencies in teaching and learning. In South Africa, arguments have been made for significant investments to be made and the University Capacity Development Grant (UCDG) in particular is being used as a driver for improved outputs. Prior to its implementation in 2018, the UCDG comprised the Research Development Grant and the Teaching Development Grant. The Teaching Development Grant was intended to address low retention and throughput rates and ZAR5.5 billion was spent to this end over a 12-year period. The analysis presented here of all Teaching Development Grant budget plans and progress reports from 2007 to 2015 shows that the undifferentiated implementation of the Teaching Development Grant within a differentiated sector limited its potential for system-wide gains. Institutions without adequate resources tended to divert Teaching Development Grant funds to attend to backlogs rather than to address teaching and learning practices and such universities lost much of their allocation through the withholding of unspent funds. This blanket practice addressed the symptoms of underspending but not the structural, cultural and agential mechanisms that led to such under-expenditure. Uneven access to the limited teaching development expertise also impacted on the use of the grant. This call for a context-based approach to funding has been identified as a key success factor in grant interventions in both African and European universities. We recommend a sector-wide response in the form of a national body or plan for the benefit of all universities and investment in financial management enhancement.

SIGNIFICANCE:

• The study contributes to a better understanding of how government funding interventions can achieve intended goals. The study calls for a more contextualised approach to funding and to greater collaboration across the sector to maximise limited capacity.

Keywords: teaching development grant, historically disadvantaged institutions, historically advantaged institutions, University Capacity Development Grant, dropouts, graduation rates

Introduction

With increasingly constrained funding available for higher education, performance-based funding regimes have been championed worldwide as a tool to steer universities towards improved quality and efficiency.1-3 The University Capacity Development Programme, introduced in South Africa in 2018, was developed to promote staff development, curriculum development and student success in the system.4 This programme includes the University Capacity Development Grant (UCDG) which is allocated to all public universities. The UCDG continues and extends the bold goals of the Teaching Development Grant (TDG) and the Research Development Grant (RDG) which have been in place, with variations in formula, since 2004. The collapsing of the RDG and TDG into the UCDG emerged in part in response to limited capacity for grant management at national and institutional levels and also as an attempt to steer the system into an integrated approach to institutional planning of research and teaching and learning activities, development and resource allocation.5

The RDG was introduced to build staff research capacity at all South African public universities and the TDG to support the enhancement of teaching and learning. The introduction of the TDG followed the publication of cohort studies of all first-time entering students conducted by the then Department of Education.6 A subsequent in-depth analysis of cohort data was commissioned by the Council on Higher Education.7 Such studies6,8 indicated serious inefficiencies in the system, whereby only 33.9% of students studying in 3-year programmes were able to successfully complete their programmes within 4 years. The studies also looked at a longer period of 6 years, where only 47.1% of the studied cohort had graduated. Of further concern was that student performance was racially skewed, with African students, despite having the highest enrolment increases since the end of apartheid, being the poorest performers, with only 21.6% graduating in a 4-year period; 27.5% of mixed-race students graduated during this time, 32.1% of Indian students and 46.2% of white students.6,9,10 A recent study10 has shown a slight improvement in these output indicators but they remain low and racially skewed.

This social justice crisis is exacerbated by the low participation rate in higher education of youth 18 to 23 years of age, which in 2016 was around 19.1%.11 Closer scrutiny shows that there are also significant discrepancies within participation rates with mixed-race and African students at 16.3% and 15.6%, respectively, and those for Indian and white students at 49.3% and 52.8%, respectively.10,12,13 The call to address persisting inequities in access has been made by numerous stakeholders14-17 and was also particularly observed in the 2015 and 2016 student-led protests which emerged in the form of the #feesmustfall and #rhodesmustfall movements17,18. These institutional protests called for an end to exclusionary cultures and structures at South African universities.17,18 The protests highlighted that the university system was not serving South Africa's diverse society equally - be it through the fee structures, institutional traditions, curricula, or pedagogical approaches. Emerging from these protests was the 'assertion of the importance of concrete transformation and decolonisation in South African universities'17. The TDG thus became even more critical to achieve the transformation agenda.

The TDG was introduced in 2004 as part of the annual block grant that the South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) pays to institutions and then as an earmarked grant from 2006. Earmarked grants are implemented to achieve particular policy goals and for which reporting on the use of such funds is required. Using earmarked funding to drive specific agendas is common around the world, and is variably known as project funding, set-asides, targeted funding or reserved funding.19-21 The introduction of the TDG can be seen as an ambitious project that put teaching development at the forefront of the sector's conversation. TDG allocations to universities were differentiated in that amounts were based on the throughputs achieved by each university. This differentiated approach allowed universities achieving relatively low throughputs to be allocated larger amounts of TDG funding than those with higher throughputs.

In 2008, a review of the TDG was published, which argued for more focused use of the funds and recommended strengthened oversight on the part of government and better accountability by universities. Until the end of 2012, however, reporting on the use of funds remained through unaudited progress reports and accountability and monitoring structures were weak.13,22 Despite the 2008 report and other calls in the literature for more focused interventions23, it was not until 2013 that a policy to more explicitly guide and monitor usage was put in place. The delay can be attributed to capacity constraints at a national level9,22 and to the restructuring of the DHET during that period. Calls for greater accountability regarding the use of state funds are an international phenomenon24, and with ZAR5.5 billion spent on the TDG25 over a 12-year period, and ongoing funds committed through the UCDG, it is imperative that we identify and address constraints on its potential to bring about improvements in teaching across the sector.

Methodological approach

It cannot be taken for granted that significant financial investments in education will lead to improved teaching and learning.3,24,26,27 It is thus essential to make sense of how the TDG has been utilised and whether its implementation has resulted in system-wide gains. Here we draw from multiple data sources.28 The 2008 TDG review report and TDG policy documents, such as the grant implementation criteria, were analysed alongside 343 documents relating to every public university in South Africa from 2004 to 2015 in the form of TDG budget plans, which detail how each university planned to use its allocated TDG funds and annual TDG progress reports, which contain financial reporting and narratives of TDG utilisation at each university.

Institutional and individual identities have been concealed. Institutional data references include mention of history, that is, historically disadvantaged institutions (HDIs) and historically advantaged institutions (HAIs) and merged institutions. Under apartheid, HAIs were designated for people of European descent and HDIs were designated for other population groups. Resource allocation and institutional autonomy were significantly skewed in favour of the HAI and apartheid legacies remain in evidence. The 'merged institutions' are those for which a merger process resulted in institutions that cannot be readily characterised as either HAI or HDI. Similar observations of resource differentiation have been made across sub-Saharan African higher education systems plagued by colonial legacies.24

Making sense of a phenomenon such as the TDG requires an analytical framework that allows for the investigation of complex social events.27 Archer29,30 posits that events and experiences in society emerge from the complex interplay of structural, cultural and agential mechanisms. She describes structures as social arrangements, resources or relations amongst social positions, as well as institutional and national arrangements, whilst culture refers to accepted, ingrained practices. Agency refers to the human ability to take action31 and it is understood that the ability of agents to pursue their projects and interests will be enabled or constrained by pre-existing cultures and structures in which they find themselves. An understanding of these interactions provides explanatory power of how practices have emerged and persisted or been transformed in the sector. In order to understand events in the social world, Archer29,30 argues that we need to enact analytical dualism so that, for the purposes of analysis, we separate out structure, culture and agency and identify the workings of each. In this study, we identified structures, such as resources, policies and offices that either enabled or constrained TDG implementation, certain cultures in the form of institutional practices that shaped TDG implementation and agential action that shaped TDG activities.

In the remainder of this article, we present three key issues that emerged in the data as constraints on the implementation of the TDG: these are financial constraints in the system, withdrawing of funds, and the uneven distribution of expertise both to lead and to implement teaching development initiatives.

Financial constraints in the system

South African universities operate in an environment profoundly affected by the socio-economic and politico-geographical realities of apartheid.14,32 HDIs in particular struggle with shortages in areas such as basic operational funds, library resources, computer systems, accommodation for students, lecture venues and laboratories.9,33-35 A grant specifically earmarked to address historical structural inefficiencies, the HDI Development Grant, was only effectively implemented in 2016.

The data show that this context significantly impacted on TDG implementation, with funds often being spent on infrastructure instead of on teaching development initiatives:

The TDG plays an important role for the capital acquisition plan and teaching equipment maintenance. (Merged Institution 15)

In the absence of ... laboratory facilities ... we are obliged to outsource the teaching of some of the undergraduate courses to [nearby historically advantaged university]. The university thus requests funding for the enhancement of University-wide Teaching & Learning infrastructure. (HDI 19)

[Merged institution] relies to a large extent on the annual earmarked funds from DHET to acquire and maintain capital equipment and educational technology. (Merged Institution 17)

The TDG funds, particularly in the early years of implementation, were seen by many institutions to be for the purpose of upgrading and maintaining basic infrastructure.

... [there is an] unequal T&L [teaching and learning] infrastructure and unequal service provision on the different sites. In order to address this challenge the TDG was utilised mainly for providing equity on all learning sites in terms of computers in laboratories, laboratory equipment, audio visual technology, minimum standard in classrooms. (Merged Institution 17)

It is estimated that an amount of R1.5 million would be required to bring equipment in lecture theatres on all campuses to an acceptable standard ... In our view, teaching development funds in 2007 could legitimately be applied to this purpose. (Merged Institution 8)

Chronic historical under-resourcing meant that the funds were used very loosely, and often in ways that had only tenuous links to the grant's purpose of improving teaching. Such approaches generally left teaching development untouched.23 These practices were mainly evident in HDIs and on HDI campuses that had merged or been incorporated with HAIs.

Infrastructure is a necessary precondition for good teaching, so it is difficult to argue against the use of funds on such items. However, infrastructural requirements are not a sufficient condition for good teaching, nor are they the purpose of the grant as set out in the TDG documentation.

Some universities, in particular HAIs, had structural enablements to generate revenue from investments and third-stream income14,15,36, which allowed them to augment the TDG funding and undertake larger-scale and more sustainable projects.

...[the project] would suffer a huge setback in their efforts at improving student retention and graduations, if the systems were abandoned as a result of diminished funding. In response, the university executive approved a special appropriation from the university's Main Fund to complement the DHET Grant... (HAI 8)

While the data reveal financial augmentation of TDG projects at a number of HAIs, they also show that other institutions, mainly ruralbased HDIs, were dependent on government funding with limited access to other sources of funding. This had particular implications given the misalignment of the government's financial year (from April to March) to that of universities' academic year (from January to December). Universities were required to submit progress reports at the end of April in each financial year to report on the utilisation of funds from 1 April of one year to 31 March of the next year. In reality, the stringent administration process necessary for the release of the funds, such as the assessments of progress reports (which took months), often meant that funds were not released until the third or even fourth quarter of the year. This had dire consequences for many institutions which were often then unable to implement their teaching development plans.

Sourcing experts to run workshops on particular areas of need ... delayed due to late confirmation from DHET. (HDI 5)

funds arrive in the 3rd month, when half of semester one has already been completed. (Merged Institution 4)

Where there was financial capacity to advance the funds using internal monies, plans could be implemented from the beginning of the year while other institutions had only 4-6 months in which to do so. That the TDG implementation processes did not acknowledge these structural differences meant the potential gains of the TDG were limited at some universities.

The advancing of funds was impossible for some institutions with very limited internal reserves. Advancing of funds can also be seen to be an issue of how risk averse the financial management culture was within the university: while some universities were willing and able to advance internal funds for TDG projects, others that potentially had funds that could temporarily have been diverted to the projects were not willing to do so.

With the implementation of the UCDG in 2018, universities now receive funds at the beginning of the academic year. Despite this positive change in the national management of the earmarked grant, universities are still struggling to spend their approved budgets. At the end of the 2018/2019 financial year, about ZAR120 million of UCDG funds remained unspent. This suggests that underlying mechanisms shaping the inability of institutions to spend earmarked funds remain unaddressed.

Financial constraints were not only in relation to infrastructure and inability to augment or advance TDG monies, but also pertained to the expertise required to manage the funds. Problems related to the administration of the grant were often tied to the ways in which the institution was managed, providing what Archer29,30 would term a structural constraint. There were ample examples in the data of institutions finding it difficult to track TDG expenditure or to ensure its use on approved items.

About R35 million was apparently utilised for other organisational business. The university management has promised to reverse this situation and also ensure the proper utilisation of earmarked funding. (HDI 20)

At the moment, we are unable to provide a complete picture of how the above allocations have been expended by the various Departments ... we request permission to submit the actual financials at the end of May. (HDI 10)

There are delays in filling ... positions due to very slow administration processes ... (HDI 20)

Overly bureaucratic administrative systems were reported in much of the data as a major constraint on the use of funding. Institutions with weak administrative systems were severely constrained in the implementation of the TDG. The failure of universities to utilise funds and to submit project plans and annual review processes on time suggests an institutional ethos that had been, at times, in crisis management mode.37 In such cases, universities had no clear distinction in the roles of the governing body (Council) and leadership and management led by the Vice-Chancellor and Senate.37,38

Not much consideration was given to how the TDG could act as a mechanism to address issues of pedagogy and curriculum development at an institution-wide level. Many of the reports hinted at fairly ad-hoc project implementation and many proposals comprised multiple small projects to be run by individuals without an overarching institutional plan.

The institutional structures and cultures then curtailed the agency of those expected to manage and implement TDG projects.39

The University acknowledged that interventions introduced in the past had not been sufficiently effective because of a lack of ownership by the Faculties. The University has introduced the position of Executive Deans in the four Faculties with, amongst others, responsibility for all teaching and research management of the Faculty. (HDI 23)

... our Departments were not fully aware that the grant existed and what it was for. . Implementation was . somewhat delayed and monitoring has not really taken place sufficiently. (Merged Institution 4)

The combination of only being able to implement the planned TDG initiatives once the funding was received and having weak financial management systems with onerous bureaucratic requirements resulted in significant portions of the money remaining unspent and being withdrawn.

Withdrawing of unspent funds and resultant fluctuations in budgets

The process of withdrawing unspent TDG funds was introduced in 2013 and is a practice that has continued with the implementation of the UCDG. Given the loose ways in which the funds were used before 2013, it was indeed necessary to improve the DHET's oversight function.40,41 This translated into the withdrawing of unspent funds through the withholding of the equivalent amount from the next year's grant.

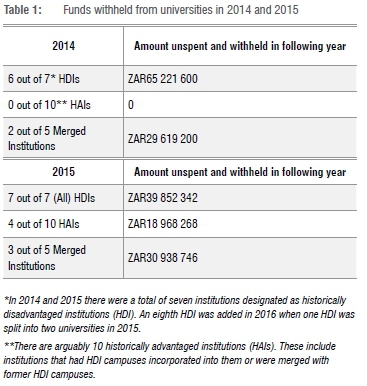

This approach meant that while amounts had been specified for each university, the actual grant was largely dependent on successful expenditure in preceding years. In some cases, funds were withdrawn due to misuse, but much more common was that the initiatives for which the funds were intended were not implemented, leaving substantial funds unspent. The table below shows the funds that were withheld in 2014 and 2015 after the implementation of the 2013 TDG policy.

The HDIs were most affected by the more stringent monitoring processes given their incapacity to spend. The withheld funds were reinvested in collaborative projects which all universities could then access. In 2015, a portion of 7%, and in 2016 a portion of 10%, was top-sliced from each grant to contribute to the national collaborative funds.40,41 In addition to these funds, the collaborative project pot was topped up with withheld funds. Institutions that were not able to spend their funds thus contributed more to the collaborative projects than those that had the capacity to spend their own funds.

This approach better served institutions that had the capacity to spend as they first benefitted from their institution's TDG funds, and then from the collaborative projects. The structural inequalities were thus unintentionally reproduced through this process with the net distribution effect of the grant potentially being regressive and having the potential of widening the system's resource inequality gap. Similar observations have also been made in European university systems whereby 'those who perform well receive more money and thus have a relatively better position to perform in the next period, while those who performed less well receive less money and are thus in a weaker position for the future'42. This can lead to entrenchment of divisions.

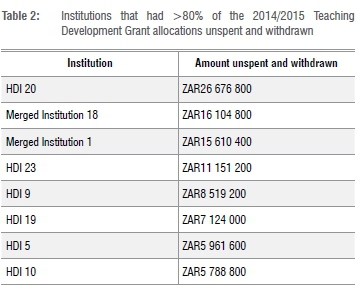

While the amount allocated to each university was based on throughput statistics, the actual monies received were determined largely by institutional ability to manage budgets and implement projects. In some cases, the unspent funds constituted as much as 80% of the allocations.

Under apartheid, HDIs were allocated a prescribed annual budget which had to be spent within the calendar year. Such universities were neither permitted to invest funds nor to roll funding over to the next year. This historical practice of withdrawing unspent funds from HDIs constrained these universities from building financial management capacity and often led to a rush of spending towards the end of the year.14,15 The withholding of TDG funds to ensure efficient spending now had the unintended consequence of echoing past practice.

The withdrawal of unspent funds does not address the underlying mechanisms constraining institutions' abilities to spend. Experience elsewhere in Africa has shown that the withholding of unspent funds encouraged unintended practices such as 'over-spending [in non-beneficial areas] and the misspending of funds'26(p.46) by highly centralised administrative systems.

In something of a vicious cycle, the risk in going ahead with planned projects prior to funding being received was much greater for HDIs which may not actually receive their full funds due to underspending in the previous years; but by not going ahead, the chances of funds being withheld increased. Those universities that could advance funds and were willing to take the risks associated with doing so were the same institutions that could spend their full funds and were thus unlikely to experience fluctuations.

The withholding of funds limited agential decisions as to how far universities could implement projects and this further shaped the type of projects that emerged. Sadly, this constraint was experienced particularly at those universities that largely depended on the TDG. The unpredictability of annual allocations posed challenges with regards to the continuity and full implementation of systematic longer-term interventions and, in some cases, this led to the suspension of such initiatives altogether. In as much as some23,43 have argued for increased education investments for targeted interventions, this research highlights the constraints existing in the system that prevent universities from using the allocated funds appropriately. Money alone is not sufficient to bring about teaching development.

The uneven distribution of expertise in the higher education system

The unequal distribution of academic development expertise was a constraint on the successful implementation of teaching development programmes.6 Jacob et al.44 point out that shortage of expertise is arguably the greatest challenge facing African higher education systems. There is a need for a cadre of strong academic development structures and a critical mass of agents who can drive teaching development across the sector. However, the data indicate that some institutions experienced acute problems with attracting staff to implement TDG projects.45 The ability to attract and retain staff is linked in part to apartheid differentiation16,46 whereby HAIs are in urban settings while HDIs are in rural locations9,47. (The exceptions to this are the University of the Western Cape which is an HDI in an urban area and Rhodes University which is an HAI in a rural area).

The literature points to a number of problems in how teaching development work is undertaken. Quinn and Vorster48 show that many attempts rely on problematic common-sense approaches which do not take theorised work on teaching and learning into account. An analysis of academic development centres at eight South African universities concluded that contextual features had a significant effect on the quality and uptake of professional development.34

The problems identified in the literature were evident in the data and were exacerbated by the nature of employment being offered. Generally, staff employed to drive TDG initiatives were employed on short-term contracts. The kind of expertise required to develop teaching is unlikely to be available under such conditions. Some universities were willing to take the financial risk of hiring people on 2- or 3-year contracts, secure in the knowledge that they would receive their full TDG allocation in those years. Other institutions were unable or unwilling to take such a financial risk and so hired people only as the annual TDG funding came in for what remained of that year. In many cases, such people, who would be responsible for working with academics on initiatives such as enhancing epistemological access by developing student writing or assisting academics in re-curriculation, were hired in administrative posts rather than as academics. This negatively impacted on who applied for such positions and what the minimum requirements were, limiting the credibility and the capacity of the incumbents.

Six universities reported in much detail on their inability to fill crucial posts, which prevented them from implementing most of their TDG projects. The inability of universities to fill vacant posts, be it due to the way the posts were structured, bureaucratic recruitment processes, or the inability to retain staff, jeopardised project implementation.

The thin distribution and stalled development of academic development expertise was evident in this study as those who were appointed were often not experts in the field having no structures to draw from in the implementation of teaching development strategic decisions.49This constrained them from 'articulating shared interests, organising for collective action, generating social movements and exercising corporate influence in decision-making as an empowered corporate agent would'29(p.269).

The individuals driving TDG projects within universities would, according to Archer29,30, need to see this work as complimentary to their academic identities and capabilities. But even where this may have been the case, agency alone is insufficient. The exercise of agency to drive the TDG projects was conditioned by the nature of structures and cultures shaping the environment.29,30 Many South African universities have managerial cultures with centralised power structures14,34,45,50 which constrained the agency of those who might lead development projects.

The TDG task team report argued that given the uneven distribution of expertise across the system, a national initiative should be established to provide support for universities. Such a national initiative, the report advised, 'should be focused on training and developing staff at identified institutions in T&L enhancement, together with regular monitoring of the impact of such interventions'.6,30 Shay43 and Boughey23 make arguments for focused system-level investments and interventions that look at curriculum structures and pedagogy to address sector-wide teaching output inefficiencies. While a national body has not been established to provide a base of such skills, the DHET did in 2015 launch the national collaborative programme, and although this programme is still in its infancy, it has already borne a number of inter-institutional projects.

Alongside the uneven teaching development expertise, the instability of management personnel to lead the TDG implementation also emerged in the data as a key constraint across the higher education system:

Due to challenges experienced in the finance department following the suspension and finally resignation by the then Director of Finance, the process of utilisation of the TDG was delayed. (HDI 19)

Leibowitz et al.34 indicate that strong leadership that contributes to cultures of professionalism is needed for teaching and learning enhancement. Corporate agents, agents with significant institutional power29, are key to the success of teaching development work, thus the high turnover of such agents destabilised potentially enabling structures such as systems, processes and procedures of operations at universities.17,51,52 Five universities have been placed under administration in the past 10 years28,37, and two of these universities have been placed under administration more than once. This instability greatly constrained the use of the TDG for strengthening teaching in these institutions.

It should not be suggested that TDG implementation was without challenges in institutions where enabling mechanisms were in place. Despite some universities having implemented academic development work for more than 30 years, the uptake of this work was uneven. At times, individuals within institutions with less hierarchical cultures used notions of academic freedom to resist change and the institutional culture entailed engagement with teaching development on a voluntary basis, whereby those who dismissed the notion of teaching development could simply ignore such initiatives.53

Programme is moving ahead smoothly. Challenges to get buy in from all lecturers. (HAI 2)

Faculties are [only] now beginning to be supportive of the integration of writing support into mainstream curricula. (HAI 22)

Conclusion

We have distinguished between the differentiated distribution of the TDG, which was based on institutional throughput rates, and the undifferentiated implementation of this grant, through which universities were expected to use, manage and report on their funds in a uniform process. We highlight that, as much as some43 have argued that increased investments are needed for improved teaching and learning, an increase in funding is not sufficient because structural and cultural constraints for appropriate implementation persist. Environmental factors shape institutional contexts and affect the possibilities of educational investments resulting in intended benefits. We argue that uniform implementation has constrained the potential to result in system-wide gains. The blanket implementation translated into some universities being better able to achieve gains from the TDG than others.

The practice of withdrawing unspent funds addressed the symptoms of underspending and not the structural, cultural and agential mechanisms that led to such under-expenditure. The blanket approach ignored the starkly differentiated nature of the system. This process did little to strengthen the positions of institutions that face large-scale inequities and constraints in their institutional structures. The HDIs which serve the most disadvantaged students arguably needed these funds the most given their historically based constraints for teaching and learning support, but they were also the most likely to have unspent funds withheld.14,15 While a national academic development structure may bring problems in the provision of contextualised initiatives, it would seem that this might be a necessary process to more widely distribute the gains the TDG offers. Increased emphasis on collaborative grants that bring institutions together would also seem to be a useful mechanism to address constraints within specific universities. As a single public higher education system, the health of any one university relies heavily on the health of the sector as a whole.

Our study also shows the urgent need for improved grant management and financial processes in many universities. It would, however, be a mistake to interpret this as a need for more compliance structures. Instead, the data suggest this is a cultural issue, in Archer's29,30 terms, requiring shared ownership of the teaching development project within the university. Management, administrative and academic staff need to have a commitment to reducing bureaucracy and efficiently implementing projects directed towards the development of teaching, and ultimately the improvement in student retention and throughput. This requires funding focused on ensuring improved financial management capacity with a concomitant reflection on institutional ethos.

The findings of this study that point to the problematic undifferentiated implementation of the TDG in a differentiated higher education sector are also applicable to other state interventions such as the Clinical Training Grant, Infrastructure and Efficiency Grant, the Foundation Provisioning Grant, the HDI-DG and the Veterinary Sciences Grant.

This article focuses on the constraints in the use of TDG funding and calls for them to be addressed, but this should not be read as a dismissal of the many successful interventions that have been implemented over the last dozen years. The history of the TDG traces numerous improvements in the management and use of the grant at both sector and institutional levels over time, and we argue that the recommendations from this study can ensure even better gains.

As the world moves into an uncertain financial future due to the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is expected to impact universities' budgets as they restructure their operations to combat the spread and impact of the pandemic, so careful consideration of some of these findings is needed. It is possible that earmarked funds may be used to cover the many unexpected costs now arising. We would argue, however, that teaching development is now more urgent than ever and that national collaborations will be key to our response.

Acknowledgement

This research was undertaken within the South African National Research Foundation funded Institutional Differentiation project (NRF grant 97646).

Competing interests

We declare that there are no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

T.M.: Conceptualisation, methodology, data collection, sample analysis, validation, data curation, writing - the initial draft. writing - revisions. S.M.: Conceptualisation, writing - revisions, student supervision, project leadership, project management, funding acquisition.

References

1. Sampson A, Comer K. When the governmental tail wags the disciplinary dog: Some consequences of national funding policy on doctoral research in New Zealand. High Educ Res Dev. 2010;29(3):275-289. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903277372 [ Links ]

2. Florich N. The politics of steering by numbers. Debating performance-based funding in Europe. Oslo: Rapport; 2008. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/280633 [ Links ]

3. Strehl F, Reisinger S, Kalatschan M. Funding systems and their effects on higher education systems. OECD Education Working Paper 6. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2007. https://doi.org/10.1787/220244801417 [ Links ]

4. South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). Ministerial statement on higher education funding 2018/19 and 2019/20. Pretoria: DHET; 2017. [ Links ]

5. South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). University Capacity Development Grant policy statement. Pretoria: DHET; 2017. [ Links ]

6. South African Department of Education (DOE). Report of the Task Team on Higher Education Teaching Development Grants. Pretoria: DOE; 2008. [ Links ]

7. South African Department of Education (DOE). White Paper 3: A programme for the transformation of higher education. Pretoria: DOE; 1997. [ Links ]

8. Scott I, Yeld N, Hendry J. A case for improving teaching and learning in South Africa in South African higher education. Higher Education Monitor. 2007;6:9-18. [ Links ]

9. South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). Ministerial Committee on the Funding Review. Pretoria: DHET; 2013. [ Links ]

10. South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). 2000 to 2008 First time entering undergraduate cohort studies for public higher education institutions. DHET: Pretoria; 2016. [ Links ]

11. South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). Post school education and training monitor. Macro-indicator trends. Pretoria: DHET; 2019. [ Links ]

12. Badsha N, Cloete N. Higher education: Contribution for the NPC's National Development Plan. Cape Town: CHET; 2011. [ Links ]

13. South African Council on Higher Education (CHE). South African higher education reviewed - two decades of democracy. Pretoria: CHE; 2016. [ Links ]

14. Bozalek V Boughey C. (Mis)framing higher education in South Africa. Social Policy Admin. 2012;46(6):688-703. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00863.x [ Links ]

15. Bunting I. The higher education landscape under apartheid. In: Cloete N, Maassen P Fehnel R, Moja T, Gibbon T, Perold H, editors. Transformation in higher education. Higher Education Dynamics. Dordrecht: Springer; 2006. p. 35-52. [ Links ]

16. Muthama E, McKenna S. The contradictory conceptions of research in historically black universities. Perspect Educ. 2017;35(1):129-142. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593x/pie.v35i1.10 [ Links ]

17. Nyamnjoh A. The phenomenology of Rhodes Must Fall: Student activism and the experience of alienation at the University of Cape Town. Strat Rev South Afr. 2017;39(1):256-277. [ Links ]

18. Qwabe N. Protesting the Rhodes Statue at Oriel College. In: Chantikule R, Kwoba B, Nkopo A. editors. Rhodes Must Fall. The Struggle to Decolonise the Racist Heart of Empire. London: Zed Books; 2018. p. 6-16. [ Links ]

19. Geuna A, Martin R. University research evaluation and funding: An international comparison. Minerva. 2003(41):277-304 https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MINE.0000005155.70870.bd [ Links ]

20. Andoh H. Understanding the impact of grants at universities. University World News. 2019 June 14. Available from: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20190611124156418 [ Links ]

21. Grove L. The effects of funding policies on academic research [doctoral thesis]. London: University College London; 2017. [ Links ]

22. South African Department of Higher of Education and Training (DHET). Ministerial statement on the use and management of the Teaching Development Grant. Pretoria: DHET; 2013. [ Links ]

23. Boughey C. Using the curriculum to enhance teaching and learning. S Afr J Sci. 2018;114(9-10), Art. #a0288. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2018/a0288 [ Links ]

24. Randriamahenintsoa E. Challenges and opportunities of higher education funding policies and programs in Madagascar. In: Teferra D, editor. Funding higher education in sub-Saharan Africa. London: Palgrave MacMillan; 2013. p. 147-183. [ Links ]

25. South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DOE). External report. Information on the state budget for universities. Pretoria: DOE; 2016. [ Links ]

26. Yigezu M. Funding higher education in Ethiopia: Modalities, challenges, opportunities and prospect. In: Teferra D, editor. Funding higher education in sub-Saharan Africa. London: Palgrave MacMillan; 2013. p. 38-70. [ Links ]

27. Ishengoma J. Funding higher education in Tanzania: Modalities, challenges, prospects and a proposal for new funding modalities. In: Teferra D, editor. Funding higher education in sub-Saharan Africa. London: Palgrave MacMillan; 2013. p. 214-246. [ Links ]

28. Moyo MT. An analysis of the implementation of the Teaching Development Grant in the South African higher education sector [PhD dissertation]. Grahamstown: Rhodes University; 2018. [ Links ]

29. Archer M. Realist social theory: The morphogenetic approach. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [ Links ]

30. Archer M. Culture and agency. The place for culture in social theory. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [ Links ]

31. Porpora DY. Morphogenesis and social change. In: Archer MS, editor. Social morphogenesis. Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. p. 25-37. [ Links ]

32. South African Council on Higher Education (CHE). Learning to teach in higher education in South Africa: An investigation into the influences of institutional context on the professional learning of academics in their roles as teachers. Higher Education Monitor. 2017(14):26-33. [ Links ].

33. Boughey C, McKenna S. A meta-analysis of teaching and learning at five historically disadvantaged universities. Pretoria: CHE; 2011. [ Links ]

34. Leibowitz B, Bozalek V Van Schalkwyk S, Winberg C. Institutional matters: The professional development of academics as teachers in South African higher education. High Educ. .2015;69:315-330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9777-2 [ Links ]

35. South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). Report on the Ministerial Committee for the Review of the Provision of Student Housing at South African Universities. Pretoria: DHET; 2011. [ Links ]

36. Ntshoe I, De Villiers P. Steering the South African higher education sector towards transformation. Perspect Educ. 2008;26(4):17-27. [ Links ]

37. Parliamentary Monitoring Group (PMG). Universities under administration: Update by Department of Higher Education and Training, South African Parliamentary Committee on Higher Education [webpage on the Internet]. c2013 [cited 2020 Jan 13]. Available from: https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/16185 [ Links ]

38. De la Ray C. Governance and management in higher education briefing paper prepared for the Second National Higher Education Transformation Summit [document on the Internet]. c2015 [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.justice.gov.za/commissions/feeshet/docs/2015-HESummit-Annexure15.pdf [ Links ]

39. Colbeck C. How does a national research/education funding policy influence academics' professional identities and careers? Paper prepared for the Colloquium on International Policies and Practices for Academic Enquiry; 2007 April 20; Winchester, UK. [ Links ]

40. South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). Ministerial statement on university funding. Pretoria: DHET; 2012. [ Links ]

41. South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). Ministerial statement on university funding. Pretoria: DHET; 2015. [ Links ]

42. Pruvot E, Claeys-Kulik A, Estermann T. Designing strategies for efficient funding of universities in Europe. Brussels University European Association; 2013. [ Links ]

43. Shay S. Educational investment towards the ideal future: South Africa's strategic choices. S Afr J Sci. 2017;113(1/2), Art. #2016-0227. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2017/20160227 [ Links ]

44. Jacob W, Xiong W, Ye H. Professional development programmes at world class universities. Palgrave Commun. 2015;1(15002):1-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2015.2 [ Links ]

45. Garraway J, Winberg C. Reimagining futures of universities of technologies. Crit Stud Teach Learn. 2019;7:39-60. http://dx.10.14426/cristal.v7iSI.194 [ Links ]

46. South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). Report on the ministerial committee for the review of the provision of student housing at South African universities. Pretoria: DHET; 2011. [ Links ]

47. Buhlungu S. Speech on the occasion of inauguration of Vice-Chancellor of the University of Fort Hare [document on the Internet]. c2017 [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.ufh.ac.za/files/Vice-Chancellor%20InaugurationX20speech.pdf [ Links ]

48. Quinn L, Vorster J. Theorising the pedagogy of a formal programme for university lecturers. In: Quinn L, editor. Re-imagining academic staff development: Spaces for disruption. Stellenbosch: Sun Media; 2012. p. 51-69. [ Links ]

49. Boughey C. Linking teaching and research: An alternative perspective? Teach High Educ. 2012;17(5):629-635. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.725528 [ Links ]

50. White K, Carvalho T, Riordan S. Gender, power and managerialism in universities. J High Educ Policy Manage. 2011;33(2):179-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2011.559631 [ Links ]

51. D'Andrea V Gosling D. Improving teaching and learning. A whole institutional approach. London: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press Imprint; 2005. [ Links ]

52. Luckett K. Working with 'necessary contradictions': A social realist meta-analysis of an academic development programme review. High Educ Res Develop. 2012;31(3):339-352. https://dx.doi.101080/07294360.2011.631518 [ Links ]

53. McKenna S, Boughey C. Argumentative and trustworthy scholars: The construction of academic staff at research-intensive universities. Teach High Educ. 2014;19(7):825-834. http://dx.doi.10.1080/13562517.2014.934351 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Temwa Moyo

Email: mtheto@gmail.com

Received: 16 Jan. 2020

Revised: 11 May 2020

Accepted: 19 June 2020

Published: 29 Jan. 2021

Editor: Jenni Case

Funding: National Research Foundation (South Africa)