Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Science

versión On-line ISSN 1996-7489

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.116 no.1-2 Pretoria ene./feb. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2020/6538

INVITED COMMENTARY

Environmental science investigations of folk taxonomy and other forms of indigenous knowledge

Fortunate M. PhakaI, II

IAfrican Amphibian Conservation Research Group, Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

IICentre for Environmental Sciences, Hasselt University, Diepenbeek, Belgium

Keywords: indigenous knowledge systems, indigenous taxonomy, isiZulu, herpetofauna

The strides made in standardising English and Afrikaans frog names created a gap to achieve the same for the other South African languages spoken by the majority of the country's population. This gap hints at an exclusion of indigenous languages and associated cultures from wildlife-related matters. Frog names in indigenous languages are part of mostly undocumented cultural/indigenous knowledge systems and they are subject to indigenous naming and classification guidelines. Indigenous names often have localised use due to cultural specificity.

Indigenous taxonomy is part of a pre-scientific knowledge system which is often considered a pseudoscience. However, a recent study was able to show that indigenous amphibian taxonomy from the Zululand region of South Africa's KwaZulu-Natal Province has scientific merit.1 Furthermore, the investigated indigenous naming and classification guidelines have similarities to those used when formulating Afrikaans, English and scientific names. A comparison with other indigenous taxonomy research shows that similarities also exist between Zululand's taxonomy and indigenous taxonomies of other parts of the world. Researchers also found indigenous names to be condensed forms of knowledge rather than abstract words.2 Information about species' behaviour and ecology is often contained within indigenous names.3 Linnaean taxonomy's basic structure is inspired by indigenous taxonomy's fundamental organising principles.4

Other investigations have shown that some traditional medicinal and gastronomic uses of organisms purported in South African indigenous knowledge systems have scientific validity.5,6 Conversely, overexploitation of natural resources under the guise of indigenous knowledge systems has also been reported.7,8 Cross-disciplinary research that investigates the scientific merit of indigenous knowledge systems is not meant to justify culturally motivated overexploitation. This research seeks to explore an under-investigated knowledge base while also increasing social inclusion in environmental matters. Studies of this nature are spurred on by the recent research focus on the interactions between biological and cultural biodiversity9, and the environmental science sector's acknowledgement of the coupling of ecological and social systems10. Zululand's rural setting is steeped in culture and high in amphibian diversity, and thus presented the region as an ideal area to pilot a study investigating interactions between South Africa's herpetofaunal and cultural diversity.

This pilot was completed with two major outcomes. Firstly, there is merit in researching how South African cultures interact with local biodiversity (in this case herpetofauna). Secondly, it is possible to standardise the indigenous names of South Africa's amphibians and bridge the gap left by the standardisation of names in two of the country's 11 official languages. The outcomes fulfil scientific curiosity (as this is a relatively novel research field) and also contribute to social inclusion. The social inclusion begins before the actual research takes place as one has to sufficiently integrate into the community whose culture they are researching in order to understand their ways and also introduce them to the type of wildlife research being undertaken. This integration helps with being welcomed into the community and enables discussions about potential benefits to be obtained in return for allowing the survey of elements of their culture that interact with biodiversity. Social inclusion is a clear benefit from the researcher's point of view, but for the community it may be perceived as being intangible. More tangible benefits are likely to appeal to research participants. For the Zululand community, a tangible benefit was an educational publication (a handbook) based on their knowledge of amphibians in their area. The publication was translated to their own language (isiZulu) and thus presented the additional benefit of an indigenous language being developed. Indigenous knowledge relating to amphibians has also been preserved in the process.

Employing purposive sampling to collect cultural data has a greater chance of yielding results when there is minimal negativity towards the research project. The purposive sampling of 13 Zululand community members using a semi-structured questionnaire technique allowed documentation of naming and classification guidelines used for amphibians in the area. The study's sample consisted of 3 female and 10 male native isiZulu speakers whose socio-economic status varied from unemployed to full-time students and the permanently employed. The participants were from five different parts of Zululand with similar environmental conditions. Analysis of the documented guidelines revealed that Zululand's indigenous taxonomy groups amphibian species according to their habits, habitats or appearance. Scientific taxonomy conventions also group species in a similar way. Species with similar traits are placed under uninomial isiZulu names. These single word isiZulu names correspond to either scientific genera or families (Figure 1) that are also represented by uninomial names. Zululand taxonomy's use of single word names to group species based on their biology is in line with the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature.12

The similarities between indigenous and scientific taxonomy have enabled supplementation of indigenous taxonomy guidelines with their modern knowledge counterparts. These supplemented guidelines were then used to assign individual isiZulu names to Zululand's amphibian species (Table 1). The newly formulated isiZulu species names have a meaning that is similar to English and/or scientific names and they also retain their relevance to isiZulu speakers as they are modified from existing indigenous names. When the newly formulated names are subjected to the rigour of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature12, 55% conform to the principles of binomial nomenclature as each name is composed of two words with the first word being a generic name. Due to the isiZulu language's descriptive nature, the remaining 45% of names could not conform to the principles of binomial nomenclature without their meaning being altered.

The semi-structured interview technique fostered discussions among participants of the pilot study. Those discussions presented an opportunity to document folkloric elements of the cultural knowledge system in addition to indigenous taxonomy. There is an indication that some folklore is more than mere mythical beliefs and may constitute observations of amphibian behaviour coupled with attempts to explain the observed behaviour using available knowledge. For instance, members of the Zululand community believe that grass frogs (Ptychadenidae) bring rain as they are often seen moments before a rain event. Without knowledge of amphibian biology, the repeated observation of rainfall being preceded by the presence of grass frogs may reinforce this idea of them bringing rain. With an understanding of amphibian biology, increased activity of the grass frogs would be attributed to the humid and moderate conditions associated with rain. These favourable conditions precede rainfall and thus prompt frog activity to also precede rainfall. The indigenous taxonomy and folklore investigated in the pilot study represent a few of the many elements in the relationship between biological and cultural diversity.

Other aspects of this relationship include medicinal usage, gastronomy, and traditional ecological knowledge. As a continuation from the pilot, investigations of the relationship between cultural and herpetofaunal diversity have been broadened to cover the entire country and also include reptiles. Upon conclusion of this research project it will be possible to make inferences about the state of the relationship between South African cultures and herpetofaunal diversity, and how this relationship can inform environmental policy that embraces the coupling of social and environmental systems.

Indigenous knowledge's place in science

The interaction of traditional knowledge with nature has generally been viewed to have negative environmental consequences. This view is justified by reports of environmental abuses informed by traditional knowledge.7,8 Furthermore, the view was pervasive in environmental science as evidence of less destructive interactions was limited, but it started changing when research into the relationship between biological and cultural diversity started generating evidence to the contrary. Research solely focused on understanding the relationship between the two diversities started gaining prominence in the 1990s as a concept called biocultural diversity.9 A systematic review of scientific literature on South Africa's biocultural diversity research shows that focus over a period of 28 years has collectively transcended more than 10 disciplines or fields of study. Some of this literature presents evidence of indigenous knowledge's applicability in human health science5, veterinary science14 and ecology15. The research presented is transdisciplinary as questions stemming from one discipline are answered using methods from another field of study. Transdisciplinarity is a critical, self-reflexive research approach relating societal with scientific problems and producing new knowledge through integration of different scientific and extra-scientific insights with the aim of contributing to both societal and scientific progress.16 The consideration of extra-scientific insights translates to inclusion of indigenous knowledge practitioners as well as their perspectives. This inclusion is especially vital for conservation planning which often focuses on intrinsic value of wildlife protection while disregarding people who are the ultimate beneficiaries of conservation initiatives. People's perspectives have become integral to conservation planning, and failing to integrate people lessens the effectiveness of this planning.17 In a culturally rich country such as South Africa, people's perspectives are often linked to their culture. Biodiversity is especially important to the culture of many South Africans as it features in their names, praises, folklore, art and traditional medicine. The country has a rich heritage of nature-based cultural traditions and this reiterates the importance of wildlife to the country's cultures.18 Conservation planning that embraces the complex link between biological and cultural diversity is more likely to succeed in reducing biological and cultural diversity loss, and could potentially provide effective and just conservation outcomes across different socio-ecological contexts.19 Socio-ecologically just conservation planning requires the knowledge pool from which it draws evidence to also embrace the link between biological and cultural diversity. The pilot study and its follow-up project as mentioned above aim to contribute to this knowledge pool through focusing on languages/cultures and taxa that are often marginalised from environmental science research.

Studying the relationship between South African biological and cultural diversity

The research required to inform appropriate environmental planning for the unique South African biological and cultural landscape should adequately embrace local contexts. A systematic review of 263 peer-reviewed articles shows this required research is succeeding in providing a greater understanding of the South African culture and biodiversity relationship, but the local context is not fully embraced due to knowledge gaps that still exist. Research focus is biased towards four of the country's nine provinces. Within provinces, research tends to concentrate on certain localities (Figure 2).

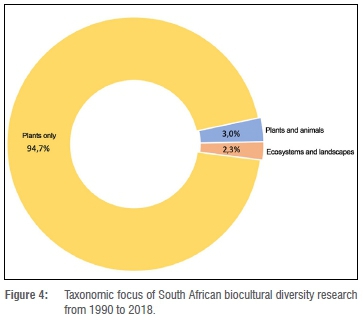

Investigations of South African biocultural diversity have steadily increased from 1990, when the biocultural diversity concept gained prominence, to 2018, when the follow-up project commenced (Figure 3). Ethical consideration or the reporting thereof was only present in 74 of the 263 articles in the review sample. Without this ethical consideration there is no assurance that researchers did not exploit human participants or subject non-human organisms to undue stress. The consideration of ethics began in 2005, the year before adoption of the International Society of Ethnobiology's code of ethics following deliberations that began in 1996.20 Ethical consideration is not extended to plants which feature prominently in this research niche as they have a weaker moral standing than humans and non-human animal research subjects. Plants dominate the focus of South African biocultural diversity investigations (Figure 4). This taxonomic bias misrepresents the proportion of taxa which interact with culture. The dominance of plants is due to their importance in traditional medicine, and this results in a bias in the field of study within which investigations are carried out. Of the 14 fields of study explored in the review sample, human health science was explored in 84% of the articles. The taxonomic bias provides motivation to increase representation of herpetofauna (along with other non-plant taxa) in research so as to make the South African biocultural diversity knowledge pool more contextually appropriate and suited to informing socio-ecologically just environmental policy.

References

1.Phaka FM, Netherlands EC, Kruger DJ, Du Preez LH. Folk taxonomy and indigenous names for frogs in Zululand, South Africa. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2019;15(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-019-0294-3 [ Links ]

2.Hidayati S, Ghani BA, Giridharan B, Hassan MZ, Franco FM. Using ethnotaxonomy to assess traditional knowledge and language vitality: A case study with the Vaie people of Sarawak, Malaysia. Ethnobiol Lett. 2018;9(2):33-47. https://doi.org/10.14237/ebl.9.2.2018.740 [ Links ]

3.Mourão JS, Araujo HF, Almeida FS. Ethnotaxonomy of mastofauna as practised by hunters of the municipality of Paulista, state of Paraíba-Brazil. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-2-19 [ Links ]

4.Ross NJ. 'What's that called?' folk taxonomy and connecting students to the human-nature interface. In: Quave CL, editor. Innovative strategies for teaching in the plant sciences. New York: Springer; 2014. p. 121-134. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0422-8_8 [ Links ]

5.Abdillahi HS, Finnie JF, Van Staden J. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-tyrosinase and phenolic contents of four Podocarpus species used in traditional medicine in South Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136(3):496-503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.019 [ Links ]

6.Harvey AL, Young LC, Viljoen AM, Gericke NP. Pharmacological actions of the South African medicinal and functional food plant Sceletium tortuosum and its principal alkaloids. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137(3):1124-1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.035 [ Links ]

7.Hunter L, Henschel P, Ray J. Panthera pardus leopard. In: Kingdon J, Hoffman M, editors. The mammals of Africa (Volume V): Carnivores, pangolins, equids and rhinoceroses. London: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2013. p. 159-168. [ Links ]

8.Dickman A, Johnson PJ, Van Kesteren F, Macdonald DW. The moral basis for conservation: How is it affected by culture? Front Ecol Environ. 2015;13(6):325-331. https://doi.org/10.1890/140056 [ Links ]

9.Maffi L. Linguistic, cultural, and biological diversity. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2005;34:599-617. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120437 [ Links ]

10.Kareiva P, Marvier M. Conservation science: Balancing the needs of people and nature. Englewood, CO: Roberts and Company Publishers; 2014. [ Links ]

11.Tarrant J. My first book of southern African frogs. Cape Town: Struik Nature; 2015. [ Links ]

12.International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Queenstown: National University of Singapore; 1999. [ Links ]

13.Zimkus BM, Lawson LP, Barej MF, Barratt CD, Channing A, Dash KM, et al. Leapfrogging into new territory: How Mascarene ridged frogs diversified across Africa and Madagascar to maintain their ecological niche. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;106:254-269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2016.09.018 [ Links ]

14.Moyo B, Masika PJ, Dube S, Maphosa V. An in-vivo study of the efficacy and safety of ethno-veterinary remedies used to control cattle ticks by rural farmers in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Trop Anim Health Pro. 2009;41(7):1569-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-009-9348-1 [ Links ]

15.Brook RK, McLachlan SM. Trends and prospects for local knowledge in ecological and conservation research and monitoring. Biodivers Conserv. 2008;17(14):3501-3512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-008-9445-x [ Links ]

16.Jahn T, Bergmann M, Keil F. Transdisciplinarity: Between mainstreaming and marginalization. Ecol Econ. 2012;79:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.04.017 [ Links ]

17.Bennett NJ, Roth R, Klain SC, Chan K, Christie P, Clark DA, et al. Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol Conserv. 2017;205:93-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.006 [ Links ]

18.South African Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA). South Africa's National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2015-2025. Pretoria: DEA; 2015. Available from: https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/publications/SAsnationalbiodiversity_strategyandactionplan2015_2025.pdf [ Links ]

19.Gavin MC, McCarter J, Mead A, Berkes F, Stepp JR, Peterson D, et al. Defining biocultural approaches to conservation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2015;30(3):140-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.12.005 [ Links ]

20.International Society of Ethnobiology. International Society of Ethnobiology code of ethics References 47 (with 2008 additions) [webpage on the Internet]. c2006 [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/ [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Fortunate Phaka

mafetap@gmail.com

Published: 29 January 2020