Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Science

versión On-line ISSN 1996-7489

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.115 no.11-12 Pretoria nov./dic. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2019/6353

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Forgiveness moderates relations between psychological abuse and indicators of psychological distress among women in romantic relationships

Richard G. CowdenI, II; Everett L. Worthington Jr.III; Brandon J. GriffinIV; Rachel C. GartheV

IDepartment of Behavioural Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIDepartment of Psychology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

IIIDepartment of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, USA

IVSan Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, San Francisco, California, USA

VSchool of Social Work, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois, USA

ABSTRACT

Forgiveness frequently occurs in a relational context and is a key ingredient for restoring and maintaining intimate relationships. Yet, certain interpersonal dynamics that sometimes motivate forgiveness (e.g. abuse) have the potential to adversely affect well-being, especially when ongoing exploitation occurs. In this study, we examined the role of forgiveness in moderating relations between psychological abuse and indicators of psychological distress in a sample of community-based South African women currently in a heterosexual romantic relationship. Participants (n=515) completed measures of decisional and emotional forgiveness of their partner, psychological abuse committed by their current partner during the course of the relationship, and depression, anxiety, and stress. Latent profile analysis identified two subgroups characterised by differing levels of forgiveness: partial forgiveness (high decisional forgiveness and moderate emotional forgiveness) and complete forgiveness (high decisional and emotional forgiveness). Regression analyses revealed that the relations of psychological abuse with depression and stress, but not anxiety, were moderated by 'forgiveness of partner'. The complete forgiveness group scored lower on depression and stress when psychological abuse was lower, but higher on each outcome when psychological abuse was higher. The findings suggest that there may be conditions in which forgiveness of partner may promote or undermine the mental health of women who experience abuse perpetrated by their current partner.

SIGNIFICANCE:

•Whereas women in continuing romantic relationships generally sought neither to avoid or seek revenge on their partners (i.e. decisional forgiveness), distinct subgroups were characterised by more or less reduction of negative emotions (i.e. emotional forgiveness).

•Within the context of continuing romantic relationships, the mental health benefits that ordinarily accompany more thorough processing of unforgiveness may be eroded when victims are exposed to severe levels of potentially ongoing psychological abuse

Keywords: decisional forgiveness, emotional forgiveness, internalising problems, intimate partner violence

Introduction

Forgiveness is a multifaceted process that involves (1) making a decision to relinquish negative behavioural intentions towards a transgressor and (2) replacing negative other-oriented emotions with positive other-oriented emotions.1,2 An abundance of research supports the mental and physical health benefits of forgiveness3, suggesting forgiveness should be encouraged. Yet, there are specific relational contexts in which the drawbacks of forgiveness for the forgiver may negate or outweigh its advantages. Research involving romantic partners (e.g. married couples) has highlighted the role of forgiveness in reinforcing negative partner behaviour.4 Other studies have found increased problem severity among those who are more forgiving of partners who frequently engage in negative, hurtful behaviours.5

Intimate partner violence and forgiveness

One category of offence that may unduly exploit forgiveness within romantic relationships is intimate partner violence (IPV) - an umbrella term encapsulating physically, sexually and psychologically abusive behaviour committed by a current or former partner.6 Evidence suggests that forgiveness offered by victims of IPV may contribute to the continuation of the victim-perpetrator abuse cycle. For example, victims who forgive their partner for IPV are more likely to minimise partner aggression7 and return to their abusive partner after having previously left them8. These kinds of cognitive-behavioural responses represent mechanisms by which relationships with perpetrators may continue9, thereby placing victims' well-being at risk.

Several studies have reported on relations between forgiveness for various forms of IPV and the physical and mental health of forgivers. Some findings identify forgiveness as a salubrious response that may buffer against maladjustment linked to IPV. In one study, Ysseldyk et al.10 found that physical and psychological abuse moderated relations between forgiveness and depression in a cross-sectional sample of female undergraduate students. In particular, forgiveness yielded stronger negative associations with psychological symptoms at higher levels of abuse compared to lower levels of abuse. Other evidence suggests forgiveness may inadvertently contribute to an enduring pattern of IPV and undermine the physical and psychological health of victims. McNulty9 investigated changes in psychological and physical aggression over a 4-year period in a sample of married couples. Findings revealed that psychological and physical aggression perpetrated by spouses tended to decline among partners who were less forgiving, but remained relatively stable for those partners who were more forgiving of their spouse. In another study focusing on mental and physical health symptom outcomes, Lahav et al.11 found that the effect of forgiveness in protecting against distress among military spouses who experienced lower levels of partner abuse was absent at higher levels of abuse. Importantly, few studies have examined links between forgiveness and IPV in low- and middle-income regions (such as those in Africa) where prevalence estimates of IPV among women are typically high.12 Prior studies in this area have also generally relied on measures of forgiveness that inadequately capture distinct decisional and emotional components, which are conceptually unrelated processes.13 In this study, we used a multidimensional approach to assess decisional and emotional forgiveness of a current, heterosexual romantic partner in a community sample of South African women.

Unique implications of decisional and emotional forgiveness

Deciding to forgive can trigger emotional forgiveness14, but the process of emotional forgiveness is not necessarily predicated on or a byproduct of decisional forgiveness. A victim can make a decision to reduce negative behaviour toward a transgressor and perhaps act benevolently toward a transgressor, yet may still experience ongoing emotional unforgiveness (e.g. anger, disappointment, resentment).1 Also, whereas the proxies of decisional forgiveness unfold at the interpersonal level (i.e. reduction of negative behavioural intentions towards the transgressor), emotional forgiveness is predominantly an intrapersonal process (i.e. reduction of negative emotions and possibly enhancement of positive emotions toward a transgressor).15

The salience of emotional and decisional forgiveness appears to vary by relationship context. When offences occur in close relationships, victims weigh relationship value cues relevant to the transgressor alongside cues associated with future risk of exploitation.16 The behavioural proxies (e.g. avoiding the perpetrator, maintaining physical distance) that might accompany a decision not to forgive romantic partners who perpetrate IPV can help to protect victims from exposure to subsequent instances of abuse, but such benefits may not outweigh the potential implications (e.g. further disintegration of a valued relationship) of deciding to withhold forgiveness.17 Victims who value the perceived benefits of the romantic relationship over the risk of future exploitation may make a decision to forgive their partner for IPV in an attempt to limit conflict, resolve relational disrepair, and restore the relationship back to pre-transgression levels of closeness.

Although withholding decisional forgiveness for IPV may serve an important role in promoting behaviours that safeguard against subsequent instances of abuse (e.g. physically distancing oneself from the transgressor), mental health benefits are usually derived by resolving emotional unforgiveness.18 Some arrangement of positive emotions is needed for victims to neutralise emotional unforgiveness; victims' net final emotional valence towards offenders may be negative (partial forgiveness), neutral or positive (complete forgiveness).14 In close and valued relationships, returning to a net positive valence towards an offender is considered a necessary part of rebuilding a healthy relationship between affected parties.19 Reducing emotional unforgiveness beyond mere elimination of negative emotions may make forgiving a valued person more difficult13, particularly as the victim attempts to absorb and make sense of being betrayed by a close person whom they trusted20,21. The efforts involved in reaching complete forgiveness may leave victims vulnerable to renewed, intensified psychological distress should they be taken advantage of again, as the distress evoked by recurring offences is likely to be compounded by victims' negative self-oriented responses (e.g. self-blame and diminished sense of self-respect) for opening themselves up to further emotional injury.22,23 Drawing on longitudinal evidence indicating that subsequent IPV is associated with increased risk of internalising symptoms (e.g. depression) even after partialling out effects of prior IPV24, recurring abuse in continuing romantic relationships has the potential to erode the mental health benefits that ordinarily accompany emotional forgiveness.

The present study

Women in continuing romantic relationships who tend to completely forgive their partners for offences involving abuse may be at risk of maintaining the cycle of abuse and their consequent psychological distress. To examine this proposition further, we applied a person-centred approach to identify unique combinations of emotional and decisional forgiveness of partner patterns among a community sample of South African women in a continuing heterosexual romantic relationship. We hypothesised that participants in each of the subgroups identified would tend to make decisions to behave differently toward their partner, yet would exhibit distinctions in processing of emotional forgiveness of their partner. We then examined whether the relations between psychological abuse and indicators of psychological distress were moderated by the forgiveness of partner profiles that emerged.

Method

Participants

A community-based sample (n=515) of South African women between 18 and 77 years of age (Mage=29.45, s.d.age=10.06) participated in this study. The majority of the sample reported being in a non-cohabiting relationship (62.72%), with the remainder either in an unmarried, cohabiting relationship (8.74%), engaged to be married (6.21%), or married (21.55%); the relationship was unspecified for 0.78% of the sample. The race distribution of the sample was largely representative of the general population, consisting of those who identified as black/African (71.84%), coloured (6.60%), Indian (10.87%), white (9.71%), and 'other' (e.g. East Asian, 0.58% or unspecified, 0.39%). Regarding religious affiliation, participants identified their affiliation as Christianity (80.19%), Hinduism (3.30%), Islam (4.08%), atheism (5.63%) or 'other' (e.g. Buddhism, traditional African religion, 5.83%; unspecified, 0.97%).

Measures

Forgiveness

Participants completed adapted versions of the Decisional Forgiveness (DFS; i.e. an intent to act differently toward the transgressor) and Emotional Forgiveness Scales (EFS; i.e. an emotional change that involves reducing negative emotions and perhaps increasing positive emotions toward the transgressor).25 Both scales consist of two subscales: DFS - prosocial intentions and inhibition of harmful intentions and EFS - presence of position emotion and absence of negative emotion. Because the subscales contain four items each, Worthington et al.25 recommend collapsing the respective subscales for use as overall measures of decisional and emotional forgiveness. In this study, items were modified to obtain a general measure of participants' decisional (e.g. 'I act friendly towards him') and emotional (e.g. 'I'm bitter about what he has done to me') forgiveness of the person with whom they were in a romantic relationship at the time of data collection. Items were rated using a five-point response format (1 = Strongly disagree; 5 = Strongly agree). Respective items were added together to derive scale scores on the DFS (ωt=0.77) and EFS (ωt=0.87). Higher scores on each scale correspond with greater decisional and emotional forgiveness.

Psychological abuse

We administered the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI)26, which is a measure of psychological abuse a woman has experienced during the course of her current romantic relationship. The PMWI consists of 58 items distributed across the dimensions of dominance-isolation and emotional-verbal abuse. In this study, participants rated the items with reference to the person with whom they were currently in a heterosexual relationship (e.g. 'He treated me like an inferior'). A five-point response format (1= Never; 5 = Very frequently) was used to rate each item. All items were summed for a global measure of psychological abuse (ωt=0.97), with higher scores reflecting greater psychological abuse.

Psychological distress

Participants also completed the 42-item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales.27 The items are evenly distributed across the three subscales of depression (e.g. 'I felt down-hearted and blue'), anxiety (e.g. 'I was in a state of nervous tension') and stress (e.g. 'I tended to over-react to situations'). In this study, participants responded to each item by considering the extent to which each statement applied to them over the last month. Responses were provided using a four-point response format (0 = Did not apply to me at all; 3 = Applied to me very much, or most of the time). Subscale scores were calculated by summing respective depression (ωt=0.96), anxiety (ωt=0.94) and stress (ωt=0.95) items. Higher scores on each subscale correspond with higher levels of psychological distress.

Procedure

Ethical permission to conduct this study was granted by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (reference number HSS/1722/016). Participants were recruited through online advertisement campaigns on a number of social media platforms (e.g. Facebook) and directed to a secure data collection site via a weblink. After voluntarily offering their informed consent, participants were presented with demographic items that contained several eligibility screening items. To be considered for inclusion in this study, participants had to be women of at least 18 years of age and in a heterosexual romantic relationship at the time of data collection. Those who did not meet either of these criteria were directed to a debriefing section to conclude participation, while eligible participants completed the measures in English.

Statistical approach

All statistical analyses were performed using R.28 Missing data diagnostics did not reveal any item-level missing data needing replacement. Skewness and kurtosis values of the primary study variables ranged from good (<|1|) to acceptable (<|2|)29, indicating that univariate normality could be assumed. Internal consistency of all measures was estimated using omega total (ωt), a procedure that is robust to violations of tau equivalence.30 Internal consistency for each measure was acceptable (i.e. >0.70).31 Pearson correlations provided an indication of the bivariate associations among the primary study variables.

Latent profile analysis of emotional and decisional forgiveness

A latent profile analysis was used to test for the existence of forgiveness of partner subgroups based on unique combinations of decisional and emotional forgiveness. Models with one to six profiles were estimated to identify the model with the best fit. Along with the bootstrap (10 000 repetitions) likelihood ratio test, we report the log-likelihood value, the Akaike information criterion, and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and its sample-size adjusted variant. Information criteria were supplemented with values that estimate the precision of profile classification, including entropy and the mean posterior probabilities of profiles for each model. Statistically significant bootstrap likelihood ratio test p-values (p<0.05), lower BIC and sample-size adjusted BIC values, and models with entropy values closer to one and mean posterior probabilities ≥0.70 for all profiles were prioritised when making decisions about model fit.32-34 The unique subgroups that emerged from the latent profile analysis formed the 'forgiveness of partner' variable.

Moderated regression of psychological abuse and forgiveness of partner

Separate multiple regression analyses were performed to examine whether 'forgiveness of partner' moderated relations between psychological abuse and indicators of psychological distress (i.e. depression, anxiety and stress). Main effects (i.e. psychological abuse and forgiveness of partner) and interaction effects (i.e. psychological abuse x forgiveness of partner) were specified for all models. The psychological abuse variable was mean centred before model estimation. Socio-demographic characteristics of age, relationship status, race and religious affiliation were included as covariates in each model. Visual inspection of quantile-quantile plots and residual plots produced via a Wallyplot technique35 indicated that the residuals for each model appeared approximately normal and homoscedastic in distribution. Collinearity diagnostics did not reveal any multicollinearity issues (all variance inflation factor values ≤3.41).

Results

Descriptive statistics for the primary study variables and zero-order correlations among them are displayed in Table 1. Both decisional and emotional forgiveness evidenced negative relations with depression, anxiety, stress and psychological abuse, although effect sizes were generally larger for emotional forgiveness (r=-0.30 to -0.45, all p<0.001) than for decisional forgiveness (r=-0.17 to -0.27, all p<0.001). Psychological abuse associated positively with depression, anxiety and stress (r=0.32 to 0.45, all p<0.001).

Latent profile analysis of emotional and decisional forgiveness

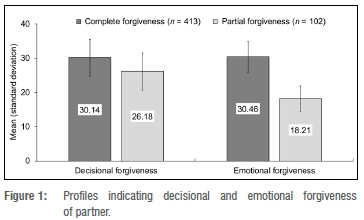

Model fit indices for each model are reported in Table 2. Bootstrap likelihood ratio test p-values for models with two and six profiles both reached statistical significance. The two-profile solution yielded the lowest BIC and sample-size adjusted BIC values, and the highest entropy value. It was also the only solution in which the mean posterior assignment probabilities were ≥0.70 and the number of assigned cases was ≥5% for all profiles. Overall, the two-profile solution yielded the best level of fit to the data. In Figure 1, we display the mean decisional and emotional forgiveness values for each subgroup.

The subgroup of participants classified into profile one (80.19%) reported similar levels of decisional forgiveness (M=30.14, s.d.=5.36) to those grouped into profile two (M=26.18, s.d.=5.40). We applied a criterion value that corresponded with a net neutral level of emotional forgiveness on the EFS (i.e. 24) to differentiate levels of emotional forgiveness. The emotional forgiveness of participants in profile one (M=30.46, s.d.=4.46) was consistent with complete forgiveness (i.e. neutral or net positive emotional forgiveness, ≥24), whereas emotional forgiveness of those included in profile two (M=18.21, s.d.=3.70) reflected partial forgiveness (i.e. net negative emotional forgiveness, <24). Based on these decisional and emotional forgiveness patterns, the subgroups were labelled complete forgiveness (profile one) and partial forgiveness (profile two).

Moderated regression of psychological abuse and forgiveness of partner

Results of the moderated regression analyses are reported in Table 3. Psychological abuse yielded positive relations with depression, anxiety and stress (all p<0.001). Forgiveness of partner was positively associated with depression (p<0.001) and stress (p =0.029), but not anxiety (p=0.063), such that the partial forgiveness group tended to report higher levels of depression and stress compared to those in the complete forgiveness group. Relations of psychological abuse with depression (p=0.043) and stress (p=0.039) were moderated by forgiveness of partner (see Figure 2), although no interaction effect was found for anxiety (p=0.164). Depression and stress were lower among participants in the complete forgiveness group at lower levels of psychological abuse, but were higher at more severe levels of psychological abuse.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to (1) identify distinct emotional and decisional forgiveness of partner patterns among a sample of South African women in ongoing heterosexual romantic relationships and (2) examine whether relations between psychological abuse and psychological distress would be moderated by the forgiveness of partner profiles that emerged. The findings revealed that forgiveness of partner experiences varied based on unique combinations of decisional and emotional forgiveness, namely partial forgiveness (i.e. higher levels of decisional forgiveness and lower levels of emotional forgiveness) and complete forgiveness (i.e. higher levels of decisional and emotional forgiveness). The focus of this study was on psychological abuse perpetrated throughout the duration of the current romantic relationship, so it is possible that behavioural proxies of decisional forgiveness (e.g. reconciliation) have a role in preserving the ongoing status of close relationships. Although victims' processing of emotional forgiveness could still be ongoing, evidence of heterogeneity in processing of emotional forgiveness suggests that victims may not necessarily return to a net neutral or positive emotional experience toward their current partner in the aftermath of an offence.

The unique forgiveness of partner patterns evidenced in this study might reflect differences in the function of victims' forgiveness. Strelan et al.36 found that forgiveness of close transgressors was more likely to be experienced out of benefit to the self and the relationship than that of the transgressor, but that forgiveness for the sake of the relationship yielded the strongest associations with forgiveness and relationship closeness. Perhaps victims in the complete forgiveness group have a preference towards relationship-focused forgiveness of their partner in order to preserve the valued relationship. On the other hand, the primary focus of forgiveness for those in the partial forgiveness group could be the self. Although self-focused forgiveness may serve to protect the victim from further emotional injury, it may be detrimental to restoration of relational closeness.

Distinctions in forgiveness observed in the current study also align with the mixture of individualistic and collectivistic principles that permeate the ways in which forgiveness is experienced in South African culture.37,38 At the expense of victims' own needs, collectivistic norms may emphasise the need for victims to forgive transgressors out of obedience to social expectations.39 Collectivistic principles might explain the decisions of those included in the current sample to forgive their partner, but processing of emotional forgiveness may depend on the extent to which victims' intrapersonal needs are adequately met.

Our results also indicate that relations between psychological abuse and indicators of psychological distress were moderated by forgiveness of partner. In contrast to the partial forgiveness group, those in the complete forgiveness group were found to be at reduced risk of psychological distress at lower levels of psychological abuse, but at increased risk of distress at higher levels of abuse. These findings resonate with previous research that has identified divergent implications of forgiveness for the mental health of victims of abuse11, particularly the notion that the protective effects of forgiveness may be eroded by abuse that occurs in continuing romantic relationships.

A useful perspective for understanding the pattern of findings in this study is need fulfilment in romantic relationships. We speculate that forgiveness (or lack thereof) for psychological abuse may promote or diminish victims' psychological well-being to the extent that forgiveness of partner contributes to the fulfilment of victims' psychological needs. In close relationships, forgiveness is thought to promote relationship-constructive behaviours (e.g. conciliatory actions) that increase the likelihood of restoring the severed relationship to pre-transgression levels of intimacy.40 Victims may offer forgiveness in order to continue receiving the psychological benefits that accompany a valued relationship16,36, but such attempts are likely to be unproductive if perpetrators' post-transgression actions are disagreeable (e.g. continued re-offending).

Drawing on several studies that have found victims' needs may be deprived when undeserved forgiveness is offered23,41, women who tend to process emotional forgiveness of their partner more thoroughly (i.e. complete forgiveness) when abuse is higher might be at risk of increased psychological distress because of the incongruency between perpetrators' post-transgression attempts at relationship reconstruction and victims' efforts to resolve emotional unforgiveness. Conversely, partial emotional forgiveness of partner may undermine psychological well-being at lower levels of abuse via the effect emotional unforgiveness (e.g. anger, resentment) has on social-cognitive processes (i.e. lower cognitive interdependence)42 that prolong relationship disintegration with the perpetrator. Unforgiveness could also have carryover effects on victims' needs to belong by reducing feelings of relatedness towards others more generally.43 Given the cross-sectional nature of the data in this study, research using methodologies that monitor changes in outcomes following specific incidents of psychological abuse is needed to understand the conditions in which type and degree of forgiveness may promote or undermine fulfilment of psychological needs.

A substantive contribution of this study is the use of a two-dimensional approach to measuring forgiveness in relation to IPV in ongoing romantic relationships. Whereas prior studies have largely focused on degree of forgiveness, the findings of this study offer additional insight into the role of decisional and emotional components of forgiveness in promoting or undermining the mental health of women who experience varying degrees of psychological abuse from their current partners. Decisional and emotional aspects of forgiveness need to be considered together when making determinations about the appropriateness of forgiveness as a treatment modality for victims of IPV. Assessments that emphasise degree of forgiveness, whilst neglecting type of forgiveness, may limit therapeutic effectiveness.

Broadening the scope of previous research that has tended to focus on abuse that transpires in situations involving conflict10, the present findings also highlight the importance of identifying effects of psychological abuse that may be perpetrated across a broader range of situations. As such, there is a need to contextualise forgiveness within a wide range of victim-partner interactions in which psychological abuse occurs. Use of measures that are sensitive to detecting covert forms of psychologically abusive partner behaviour may provide opportunities for enhancing the effectiveness of therapeutic efforts targeting forgiveness.

The current findings may help inform the clinical application of forgiveness for victims of IPV. Whereas Fincham et al.44 suggest that forgiveness of close others typically involves more than mere reduction of negativity toward a transgressor and includes enhancement of positive other-oriented emotion, this expectation may be unrealistic when a close relationship is characterised by severe or persistent abuse. For this reason, alongside making a decision not to personally retaliate against an abusive partner, therapeutic gains may be enhanced if IPV survivors establish an adaptive level of emotional forgiveness that balances the emotional burden of unforgiveness with the potential for future exploitation that might occur upon reconciliation with an abusive partner. Exploration of the meaning of residual negative feelings toward an abuser in a safe and supportive environment might be beneficial if it reveals how forgiveness operates in tandem with other character strengths, such as having the wisdom to accurately assess the quality of an abusive relationship.

Limitations and future research directions

Alongside the strengths of this study, there are several methodological limitations. Use of a cross-sectional design prevents inferences about causality and directionality. Experimental and longitudinal studies are needed to understand how the processes and outcomes of decisional and emotional forgiveness (both individually and in combination) change over time in women who experience psychological abuse in continuing romantic relationships. The findings of this study should be interpreted together with our methodological choice to assess forgiveness without reference to a specific offence involving abuse. Transgression-specific variables (e.g. recency and frequency of abuse) and relationship dynamics (e.g. commitment) likely influence victims' experiences of state forgiveness in response to specific types of abuse.

Although the sample included in this study corresponded with the diverse sub-populations of South Africa, cross-cultural generalisability of the finding may be limited. Research is needed to identify cross-cultural distinctions in the consequences of forgiveness (and unforgiveness), given that conceptualisations and tolerance of IPV differ across societies, cultures and ethnic groups. For example, Rajan's45 qualitative study involving a Tibetan group of victims, friends/relatives of victims, and perpetrators of physical partner abuse identified conditions in which abuse was perceived to be acceptable, or even justified. Along similar lines, based on evidence highlighting the role of third parties in the forgiveness process46, it would be prudent to explore the relevance and impact of broader social influences (i.e. proximodistal social factors that are beyond the victim-perpetrator dyad) in facilitating or deterring forgiveness among victims of IPV.

Conclusion

In this study, we identified the existence of two unique forgiveness of partner patterns in a sample of South African women who were in a continuing heterosexual romantic relationship, each of which exhibited distinct effects on relations between psychological abuse and indices of psychological distress. Notwithstanding the need for additional research in this area, the findings are consistent with a growing body of evidence that has identified circumstances in which the protective mechanism of forgiveness may be overwhelmed by IPV that occurs within the context of ongoing romantic relationships.

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from Templeton World Charity Foundation (TWCF0101/AB66). The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Templeton World Charity Foundation.

Authors' contributions

All authors developed the study concept and contributed to the study design; R.G.C. coordinated data collection, performed the data analyses and drafted the manuscript. E.L.W., B.J.G. and R.C.G. provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

References

1.Watkins DA, Hui EKP, Luo W, Regmi M, Worthington EL Jr, Hook JN, et al. Forgiveness and interpersonal relationships: A Nepalese investigation. J Soc Psychol. 2011;151:150-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540903368541 [ Links ]

2.Worthington EL Jr, Witvliet CV, Pietrini P, Miller AJ. Forgiveness, health, and well-being: A review of evidence for emotional versus decisional forgiveness, dispositional forgivingness, and reduced unforgiveness. J Behav Med. 2007;30:291-302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-007-9105-8 [ Links ]

3.Toussaint LL, Worthington EL Jr, Williams DR, editors. Forgiveness and health: Scientific evidence and theories relating forgiveness to better health. New York: Springer; 2015. [ Links ]

4.McNulty JK. Forgiveness increases the likelihood of subsequent partner transgressions in marriage. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24:787-790. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021678 [ Links ]

5.McNulty JK. Forgiveness in marriage: Putting the benefits into context. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22:171-175. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.171 [ Links ]

6.Breiding MJ, Basile KC, Smith SG, Black MC, Mahendra RR. Intimate partner violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [ Links ]

7.Gilbert SE, Gordon KC. Predicting forgiveness in women experiencing intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2017;23:452-468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801216644071 [ Links ]

8.Gordon KC, Burton S, Porter L. Predicting the intentions of women in domestic violence shelters to return to partners: Does forgiveness play a role? J Fam Psychol. 2004;18:331-338. [ Links ]

9.McNulty JK. The dark side of forgiveness: The tendency to forgive predicts continued psychological and physical aggression in marriage. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2011;37:770-783. [ Links ]

10.Ysseldyk R, Matheson K, Anisman H. Revenge is sour, but is forgiveness sweet? Psychological health and cortisol reactivity among women with experiences of abuse. J Health Psychol. 2019;24(14):2003-2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317714319 [ Links ]

11.Lahav Y, Renshaw KD, Solomon Z. Domestic abuse and forgiveness among military spouses. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2019;28:243-260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2018.1531335 [ Links ]

12.Devries KM, Mak JYT, García-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340:1527-1528. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1240937 [ Links ]

13.Worthington EL Jr, Brown EM, McConnell JM. Forgiveness in committed couples: Its synergy with humility, justice, and reconciliation. Religions. 2019;10:13. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10010013 [ Links ]

14.Worthington EL Jr, Scherer M. Forgiveness is an emotion-focused coping strategy that can reduce health risks and promote health resilience: Theory, review, and hypotheses. Psychol Health. 2004;19:385-405. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044042000196674 [ Links ]

15.Ysseldyk R, Matheson K. Forgiveness and coping. In: Malcolm W, DeCourville N, Belicki K, editors. Women's reflections on the complexities of forgiveness. New York, NY: Routledge; 2008. p. 143-163. [ Links ]

16.Burnette JL, McCullough ME, Van Tongeren DR, Davis DE. Forgiveness results from integrating information about relationship value and exploitation risk. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38:345-356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211424582 [ Links ]

17.Finkel EJ, Rusbult CE, Kumashiro M, Hannon PA. Dealing with betrayal in close relationships: Does commitment promote forgiveness? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82:956-974. https://.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.956 [ Links ]

18.Griffin BJ, Worthington EL Jr, Lavelock CR, Wade NG, Hoyt WT. Forgiveness and mental health. In: Toussaint L, Worthington EL Jr, Williams D, editors. Forgiveness and health: Scientific evidence and theories relating forgiveness to better health. New York: Springer; 2015. p. 77-90. [ Links ]

19.Gerlach TM, Agroskin D, Denissen JJA. Forgiveness in close interpersonal relationships: A negotiation approach. In: Kals E, Maes J, editors. Justice and conflicts. Berlin: Springer; 2012. p. 377-390. [ Links ]

20.Gordon KC, Baucom DH, Snyder DK. Treating couples recovering from infidelity: An integrative approach. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:1393-1405. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20189 [ Links ]

21.Strelan P, Karremans JC, Krieg J. What determines forgiveness in close relationships? The role of post‐transgression trust. Br J Soc Psychol. 2017;56:161-180. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12173 [ Links ]

22.Braithwaite SR, Fincham FD, Lambert NM. Hurt and psychological health in close relationships. In: Vangelisti AL, editor. Feeling hurt in close relationships. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2009. p. 376-399. [ Links ]

23.Luchies LB, Finkel EJ, McNulty JK, Kumashiro M. The doormat effect: When forgiving erodes self-respect and self-concept clarity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98:734-749. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017838 [ Links ]

24.Chuang CH, Cattoi AL, McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Camacho F, Dyer AM, Weisman CS. Longitudinal association of intimate partner violence and depressive symptoms. Ment Health Fam Med. 2012;9:107-114. [ Links ]

25.Worthington EL Jr, Hook JN, Utsey SO, Williams JK, Neil RL. Decisional and emotional forgiveness. Paper presented at: The International Positive Psychology Summit; 2007 October 05; Washington DC, USA. [ Links ]

26.Tolman RM. The development of a measure of psychological maltreatment of women by their male partners. Violence Vict. 1989;4:159-177. [ Links ]

27.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. 2nd ed. Sydney: Psychology Foundation; 1995. [ Links ]

28.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. Available from: https://www.R-project.org [ Links ]

29.Arditte KA, Çek D, Shaw AM, Timpano KR. The importance of assessing clinical phenomena in Mechanical Turk research. Psychol Assess. 2016;28:684-691. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000217 [ Links ]

30.Dunn TJ, Baguley T, Brunsden V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br J Psychol. 2014;105:399-412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046 [ Links ]

31.Crutzen R, Kuntsche E. Validation of the four-dimensional structure of drinking motives among adults. Eur Addict Res. 2013;19:222-226. https://doi.org/10.1159/000345457 [ Links ]

32.Hallquist MN, Wright AGC. Mixture modeling methods for the assessment of normal and abnormal personality. Part I: Cross-sectional models. J Pers Assess. 2013;96:256-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.845201 [ Links ]

33.Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2008;2:302-317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x [ Links ]

34.Stanley L, Kellermanns FW, Zellweger TM. Latent profile analysis: Understanding family firm profiles. Fam Bus Rev. 2017;30:84-102. [ Links ]

35.Ekstrøm CT. Teaching 'instant experience' with graphical model validation techniques. Teach Stat. 2014;36:23-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/test.12027 [ Links ]

36.Strelan P, McKee I, Calic D, Cook L, Shaw L. For whom do we forgive? A functional analysis of forgiveness. Pers Relatsh. 2013;20:124-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01400.x [ Links ]

37.Worthington EL Jr, Cowden RG. The psychology of forgiveness and its importance in South Africa. S Afr J Psychol. 2017;47:292-304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246316685074 [ Links ]

38.Cowden RG, Worthington EL, Nonterah CW, Cairo AH, Griffin BJ, Hook JN. Development of the Collectivist‐Sensitive Trait Forgivingness Scale. Scand J Psychol. 2019;60:169-180. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12519 [ Links ]

39.Hook JN, Worthington EL Jr, Davis DE, Watkins D, Hui E, Luo W, et al. A China-New Zealand comparison of forgiveness. Asian J Soc Psychol. 2013;16:286-291. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12033 [ Links ]

40.McCullough ME, Luna LR, Berry JW, Tabak BA, Bono G. On the form and function of forgiving: Modeling the time-forgiveness relationship and testing the valuable relationships hypothesis. Emotion. 2010;10:358-376. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019349 [ Links ]

41.Strelan P, Crabb S, Chan D, Jones L. Lay perspectives on the costs and risks of forgiving. Pers Relatsh. 2017;24:392-407. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12189 [ Links ]

42.Karremans JC, Van Lange PAM. The role of forgiveness in shifting from 'me' to 'we'. Self Identity. 2008;7:75-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860601182435 [ Links ]

43.Karremans JC, Van Lange PAM, Holland RW. Forgiveness and its associations with prosocial thinking, feeling, and doing beyond the relationship with the offender. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2005;31:1315-1326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205274892 [ Links ]

44.Fincham FD, Hall J, Beach SR. Forgiveness in marriage: Current status and future directions. Fam Relat. 2006;55:415-427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.callf.x-i1 [ Links ]

45.Rajan H. When wife-beating is not necessarily abuse: A feminist and cross-cultural analysis of the concept of abuse as expressed by Tibetan survivors of domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2018;24:3-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801216675742 [ Links ]

46.Green JD, Davis JL, Reid CA. Third-party forgiveness: Social influences on intimate dyads. In: Agnew CR, editor. Social influences on romantic relationships: Beyond the dyad. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2014. p. 171-187. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Richard Cowden

richardgregorycowden@gmail.com

Received: 08 May 2019

Revised: 28 Aug. 2019

Accepted: 04 Sep. 2019

Published: 27 Nov. 2019

Editor: Hester du Plessis

Funding: Templeton World Charity Foundation