Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Science

versión On-line ISSN 1996-7489

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.115 no.11-12 Pretoria nov./dic. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2019/6231

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Quality assurance agencies: Creating a conducive environment for academic integrity

Evelyn C. Garwe

Deputy Chief Executive Officer, Zimbabwe Council for Higher Education, Harare, Zimbabwe

ABSTRACT

Academic integrity is a key measure of the quality, efficiency and competitiveness of higher education systems. This article explores how a quality assurance agency can foster a conducive environment for academic quality and integrity. A self-study methodology was used, with a focus on the insights and experiences of the Zimbabwe Council for Higher Education over a 10-year period. The findings show that by assuming an innovative and transformational leadership role in instilling a culture of self-evaluation, as well as maintaining its own integrity, an external quality assurance agency can improve academic integrity. The article adds value to the existing knowledge by advancing the higher education ecosystem approach as an integrity-based panacea and conducive way to induce integrity to flow from all players as opposed to the use of heavy-handed regulatory approaches.

SIGNIFICANCE:

•This article highlights the importance of academic integrity and situates quality assurance agencies as playing a central role in fostering academic integrity

Keywords: higher education ecosystem, self-evaluation, transformational leadership, Zimbabwe

Introduction

Academic integrity refers to the adherence to a code of values and ideals (ethical standards) that inform the behaviour and conduct generally understood and accepted worldwide.1,2 This code of practice demonstrates 'a commitment, even in the face of adversity, to six fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage'3. It is a universal trust-bearing measure of the quality of academic and professional practices (teaching, learning, assessment, evaluation, research and community service) by individuals, groups or institutions within higher education systems.4,5 Accordingly, the achievement of academic integrity is a critical goal that every higher education system aspires to reach, to be part of the national and global communities of integrity.

Breaches of academic integrity through engaging in behaviour and practices that are not in keeping with expectations is referred to as dishonesty, misdemeanor, fraud or corruption.6 Denisova-Schmidt7 highlights the global challenge of dealing with the increasing incidences of 'integrity deficiencies' that undermine the trust placed in the outcomes of higher education. In the globalised world, mobility of students and workers requires recognition of their qualifications. Lack of academic integrity at individual, institutional or national level poses a significant threat to public safety in cases in which graduates have not genuinely acquired the required competencies.7 A case in point is that of professional courses (health and engineering) as well as programmes with economic bearing e.g. accounting and banking.

In order to uphold quality and standards, all players are collectively responsible for continuously scanning the environment to prevent, identify and rid academia of corruption.6-8 Although several approaches to addressing academic dishonesty have been suggested,2,9 it is generally accepted that the problem persists.

Over the last two decades, over 100 countries have established external agencies to assure quality in higher education.10 The thesis here is that higher levels of academic quality and integrity prevent and reduce academic dishonesty. Although these agencies operate within varied contexts and apply different quality assurance mechanisms, accreditation and quality audits are the most effective and widely used methods of preventing systemic academic malpractices.

This article explores how a national quality assurance agency, the Zimbabwe Council for Higher Education (ZIMCHE), improved academic integrity in Zimbabwe, a country whose high quality education11 contrasts with high levels of corruption in the wider society12,13 thus posing an enigma. The case study approach is premised on using the widely recognised method of concentrating on a context/locality and generalising therefrom.

Contextualising academic integrity in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is a medium-sized country which gained independence from Britain on 18 April 1980. The country takes pride in its relatively well-established higher education system that spans over 60 years. The first higher education institution was the University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, established in 1955, in an affiliate relationship with the University of London.14 The new government, upon gaining independence, introduced aggressive policy reforms focusing on curriculum review, inclusivity, planning and efficiency, quality and relevance. Some publications11 position Zimbabwe as the best-educated country in Africa, with literacy levels in excess of 94%.

Zimbabwe experienced a rapid expansion of higher education characterised by increasing student enrolments and new state and public institutions between 1998 and 2005. This expansion was not supported with proportionate infrastructural, human, material and financial resources necessary to maintain the original high-quality standards. This is largely explained by the fact that the country experienced economic decline during the same period, which resulted in a brain drain of highly qualified and experienced academics and other professionals.

In its quest to safeguard quality, the country established ZIMCHE in 2006, through an Act of Parliament, to regulate and promote quality in higher education.15 ZIMCHE developed a quality assurance framework to guide institutions to achieve ethical, legal and professional standards. ZIMCHE has recently undertaken a curriculum overhaul in line with the concept of University 5.0 introduced by the Minister of Higher and Tertiary Education, Science and Technology Development, Honourable Professor Amon Murwira. Two pillars of the university mandate (innovation and industrialisation/commercialisation) were added to teaching, research and community service. This move positioned higher education to contribute effectively to the national vision of achieving an upper-middle income status by 2030.

Corruption was reported to be the major cause of both Zimbabwe's economic downturn and the persistent failure to resolve the problem.12,13 These authors12,13 used the Corruption Perception Index wherein Zimbabwe featured at position 154 out of 175 most corrupt nations in the world to premise their proposition that economic improvement in the country will only commence after serious and concerted efforts to root out corruption.

Studies focusing on academic dishonesty affirmed the existence of dishonest tendencies by students, staff and management.16-18 Media reports revealed cases in which some universities awarded unmerited degrees to public figures through coercion, or voluntarily in search of favours. A case in point is the award of a doctorate to a former first lady by a reputable university in Zimbabwe. Some unregulated non-higher education institutions also sell 'honorary' doctorates and professorships to public figures - an activity that is legally a preserve of registered and accredited higher education institutions.

Cognisant of the corruption-infested national context, its global manifestation and its consequences for higher education and the wider society, ZIMCHE has played a key role in fostering academic integrity through quality assurance.

Literature review

Academic integrity breaches

There exist different kinds of integrity breaches which negatively impact quality, effectiveness and efficiency and the sanctity of higher education.19,20 Academic integrity breaches are complex in that all players in the higher education ecosystem are potential perpetrators.8 In higher education institutions, students (both at undergraduate and postgraduate levels), academic and support staff, management as well as the governing council are prone to academic dishonesty. These breaches can occur during student admissions, staff recruitment, grading, promotion, teaching, supervision, assessment, research, reporting, publication and qualification award. Examples of some of the common breaches are discussed below.

Flawed student admission, staff recruitment, grading and promotion practices

Fraudulent student admissions arise due to competition for places in high-demand programmes that are perceived to be prestigious (e.g. law and medicine). Staff are either offered or demand bribes in order to circumvent the process and admit certain students ahead of others.21 The issues of merit do not apply here because all students will be qualified but competing for limited places. Management can sometimes abuse power and appoint or promote staff members on the basis of ethnicity, gender, personal connections, family relationships, bribery or extortion.7,22 Recruitment and promotion can also be done on the basis of misrepresented qualifications, academic achievements, as well as leadership experience.23,24 This form of misrepresentation is usually done by padding resumes with exaggerated accomplishments and claims of fake qualifications including those obtained from unrecognised institutions.

Grade inflation or compression

Inflating or compressing grades happens when assessors award marks to increase or decrease grades inconsistent with the student's deserved grade.25 In addition to monetary incentives, grade inflation or compression is sometimes motivated by sexual favours. In other instances, administrative staff put pressure on academics to inflate grades for the benefit of institutional reputation. This is usually motivated by the need to get higher appropriations where institutions are funded on the basis of student throughput.25 Where students are offered merit-based scholarships, academics are inclined to give students higher grades to avoid students dropping out because they lose their scholarship, which would result in the institution losing tuition income.

Fabrication of research findings or falsification of reports

Fabrication usually occurs when research findings fail to conform to the student's or academic's preferred theory or framework. Data are then crouched or manipulated to suit the desired outcome instead of using the real data to craft new theories or create new knowledge. Academic supervisors can sometimes alter and publish the work done by students without due acknowledgement. At times academics can pay research assistants to collect data, undertake literature reviews and draft reports, which they simply spruce-up and publish as sole author.26

Plagiarism

Plagiarism involves academics or students copying other people's work (e.g. ideas, wording, approaches, artworks or inventions) with or without modification and without due acknowledgement.22 Plagiarism occurs in different forms inclusive of:

•Cyber-plagiarism, essay mills or contract cheating, wherein known or unknown (ghostwriters) third parties are contracted to undertake assignments or research on behalf of a student, staff member or contractor either physically or online.27

•Self-plagiarism involving recycling one's own work and presenting it as new.28

•Mosaic plagiarism where synonyms are used to replace words used in the original article whilst maintaining the same ideas.29

•Bureaucratic plagiarism involving abuse of power by superiors who take ownership of work assigned and done by juniors in their day-to-day work, for example reports, grant proposals, PowerPoint presentations or speeches. The superior at times acknowledges the originators but takes the limelight with little or no contribution.30 It is important to note that in some cultures, bureaucratic plagiarism is considered 'business as usual' as it is consistent with institutional and cultural norms.31

Collusion

There are still grey areas regarding the point at which collaboration becomes collusion, given that collaboration is encouraged and celebrated in academia whereas collusion is condemned.32 The confusion results from varied understandings and practices deemed appropriate regarding assessment of students in different disciplines and contexts. Collusion captures the possibility that arises when academics or students get material and ideas from unattributed sources that are not Internet-based and hence difficult to detect using electronic anti-plagiarism software, for example interactions with other students, academics or professionals.33 Collusion also occurs when students collaborate with peers on a piece of assessed work meant to be undertaken as an individual task. The group work is then customised to avoid detection. Another form of collusion is when a student or academic avails a completed assignment to another for money or other favours.

Academic integrity breaches in quality assurance agencies

Some quality assurance agencies accredit programmes/institutions fraudulently in return for bribes or favours.34 There are also fake quality assurance agencies that operate as accreditation mills.35 False audit or evaluation reports resulting from conflict of interest and bribery by peer reviewers, agency staff and board members are also common.34 Bribing or threatening (as in the case of threats by political figures or other high-ranking officials) individuals constituting accrediting panels forces or motivates them to by-pass certain criteria and produce reports in favour of the department or give the programme or institution undue advantage.

Quality assurance agencies can also plagiarise instruments and standards designed by sister agencies from other countries. In addition, peer reviewers who are engaged by quality assurance agencies have been reported to re-use the templates that they have used before in their reports (self-plagiarism). Incidents of collusion have also been reported, wherein board members, staff and peer reviewers work in cahoots to influence decisions that would otherwise not have been made if rigour was maintained. 34

Situating quality assurance agencies in academic integrity

Quality assurance agencies provide leadership in developing and maintaining a framework to guide institutions to achieve academic quality and integrity in all aspects of the university mandate. Leadership is defined as the ability to inspire, support and motivate others to achieve set goals.35 From an institutional perspective, leadership is the capacity to energise, coordinate and synergise all players towards effective goal attainment.36 Davenport and Volpel37 suggest that today's leadership should coordinate communities in their mandate areas, create user-friendly cultures and fend off bureaucracy.

Quality assurance frameworks embed academic integrity in the standards for programme/institutional accreditation and audit/review.38 Institutions are required to detail the initiatives undertaken to maintain and improve academic integrity in their self-evaluation reports.37 These claims are then validated by the accreditation and audit teams during the mandatory site visits. Placing academic integrity in the spotlight in this manner motivates higher education institutions to prioritise and actively inculcate a culture of academic integrity.38

Many quality assurance agencies use the philosophy of zero tolerance39 involving use of heavy-handed approaches (e.g. legal, software and structures) to discourage, accost and discipline those who commit academic misdemeanors.40 This approach is premised on the assumed opportunistic tendencies of human beings who largely behave according to their self-interests in order to optimise their own utility, ignoring the potential conflict of interest with their assigned duties.41 This approach of putting emphasis on detection and sanctions to achieve academic integrity as opposed to awareness, integration and promotion of desired behaviours is fraught with many challenges.42 To begin with, it focuses on inputs and process; some agencies spend a fortune on surveillance and oversight mechanisms rather than on productive and progressive work.43 Furthermore, institutions incur additional costs to prove compliance to standards.44

Approaches that are inclusive, goal and improvement-oriented influence the choice of human behaviour.45 An inclusive environment, in which every player is valued, inculcates a sense of belonging and a quest to contribute positively to set goals. The nature of the mentor-mentee relationship influences the awareness and acceptance of standards.46 Students, staff and institutions acquire habits in their interactions with faculty, management and agencies through capacity building and exemplary conduct.47 Thus the positive approach to academic integrity48 produces better results and demands that all players play their role in encouraging good conduct through leading by example and exhibiting academic integrity at the individual level.

Higher education ecosystem

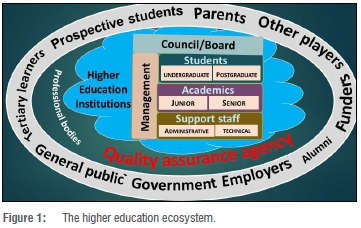

Systems theories (general, ecological, life-model, and ecosystems) embrace mutual relationships amongst elements that are part of a whole. The study adopts the ecosystem approach, a concept that has diversified from botany49 to wider application in education and other disciplines50,51. Ecosystems are functional and coordinated entities characterised by dynamic bilateral and multilateral connectivity, interdependence and interaction of different players (living and non-living) for survival and growth within a specific environment. A higher education ecosystem (Figure 1) is a self-sustained, self-regulating system of players united by shared goals and mutual interdependence based on a value co-creation approach.52

The players in the higher education ecosystem include quality assurance agencies, professional bodies, parents, general public, alumni, prospective students, funders and higher education institutions. Higher education institutions form a sub-system within the larger ecosystem which includes the university council/board, management, academics, students and support staff.53 The non-living components of this ecosystem that direct the ways the human players behave and interact51 comprise physical and material resources, policies, systems and procedures, organisational cultures, leadership styles and strategies19.

An effective ecosystem requires the cooperation of all players and the awareness of each other's presence and contributions.46 Although quality assurance agencies coordinate and regularly monitor and evaluate results of individual and collective actions of players, it is the effective interaction of all players that is responsible for achievement of goals. Unprogressive attitudes, lack of professionalism and disagreement of players in an ecosystem disrupts the smooth flow of activities and results in pollution of the whole system.19 For example, if issues of academic integrity are not well managed by institutions or agencies, the whole system will become polluted. In other words, the integrity of quality assurance agencies is integral to quality higher education systems; in the same vein, no agency can rise above the quality of its institutions - effective collaboration reinforces and safeguards academic integrity.

The success and reputation of institutions depend on the quality of their graduates; hence they have an intrinsic stake in upholding academic integrity. Quality assurance agencies should work together with institutions to develop strategies to maintain academic integrity. This calls for a positive approach wherein integrity is embedded in the self (both at individual, institutional and sectoral level) as opposed to viewing it from a negative perspective.54 This approach is premised on the stewardship theory which argues that selflessness and pro-social behaviours promote collectivism as opposed to individualism. Hence the interests of agencies are aligned to those of institutions and all other players in the higher education ecosystem.55

Purpose of study

The study was aimed at examining the role of a quality assurance agency in providing leadership in academic quality and integrity. Specifically, the study sought to answer the following questions:

1.What challenges does ZIMCHE face in rallying Zimbabwean universities around issues of quality and academic integrity?

2.How does ZIMCHE assure quality and academic integrity in Zimbabwe?

3.What lessons and good practices can be drawn from ZIMCHE's approach to academic integrity?

Methodology

Originating from the teaching practice, the self-study methodology (intimate scholarship) has gained foothold in all disciplines as an important approach to informing and transforming practice through leveraging personal and institutional experiences.56 This methodology is premised on the self-study theory which propounds continual reflection, critical examination, communication and comparison of personal and institutional activities, strategies and experience with the literature and development of innovative and effective interventions, in contrast to pursuing practices that are premised on tradition, habit or impulse.57 Although often criticised on the basis of bias and an assumed lack of objectivity, the self-introspection of the distant and immediate past as well as current experiences to interrogate and identify useful insights for improvement engenders trustworthiness and transparency.58,59 The edge of the methodology over alternatives derives from its improvement-orientation, interactivity and comparability with similar situations.57

ZIMCHE and the Zimbabwean higher education ecosystem were used as the institutional self and the ecological self, respectively. ZIMCHE started its operations in 2009 and hence has rich experiences spanning over 10 years. Using the five-step self-study guidelines recommended by Samaras and Roberts57, the author worked with colleagues within and outside ZIMCHE to brainstorm, interrogate, critique and obtain feedback regarding the three research questions identified for the study. The five steps were adapted as follows:

•Step 1: The study questions were designed due to their relevance to the improvement of academic quality and integrity. The questions were generated from observations, experiences and relevance to professional growth and quality improvement.

•Step 2: Sessions were held to brainstorm, interrogate, critique and obtain feedback from colleagues responsible for registration, accreditation, audit and compliance monitoring in ZIMCHE, quality assurance directors, registrars and academic deans, peer reviewers, ministry of higher education and professional bodies. The author held these sessions during events occurring between December 2017 to November 2018. In this way, it was possible to obtain insights and perspectives to ascertain concrete and valuable information to respond to the study questions.

•Step 3: Using the information collected, areas of good and bad practices on how to improve quality and academic integrity were identified.

•Step 4: The author packaged the study and presented the findings at a quality promotion conference on academic integrity.

•Step 5: After further refining the insights following dialogue and comments from colleagues at the conference, the final stage was to document the reflections, insights and recommendations for promoting academic integrity for publication and dissemination to the wider academic audience for adaptation and further improvement.

The findings are presented according to the responses to the first two research questions regarding the ZIMCHE challenges and approaches to quality and academic integrity. The discussion section deals with Question 3 on lessons and good practices derived from ZIMCHE's approach to academic quality and integrity.

Findings

Challenges

In pursuit of quality, ZIMCHE is expected to promote and protect academic quality and integrity by creating a conducive environment based on good governance, best practice and capacity development. The challenges faced by ZIMCHE in pursuit of this cause relate to: academic staff grading and promotion; autonomy of institutions; interpretation of quality assurance tools, policies, and standards; lengthy processes and procedures; existence of multiple regulatory bodies; and conflicts of interest.

Academic staff grading and promotion

In order to correct the existence of disparate criteria for academic staff grading and promotion, ZIMCHE harmonised these guidelines across the 20 registered universities in Zimbabwe. This standardisation applied pressure on academics to publish or perish. Whilst institutions reserve the right to establish promotion criteria with respect to teaching and community service, the ZIMCHE instrument harmonised issues to do with the quantum of research outputs. This puts pressure on academics to 'publish or perish' to such an extent that some may engage in academic integrity breaches inclusive of: publishing articles in low quality ('predatory') journals; manipulating research results; forming authorship cartels; making use of ghostwriters; or publishing on the basis of plagiarising work done by students or other sources.

Autonomy

Higher education institutions in Zimbabwe are autonomous institutions governed by an Act of Parliament for public higher education institutions and by a charter for private ones. As such, the perception within higher education institutions is that the state or state agencies ought not to interfere with the affairs of institutions. They argue that, for quality to prevail, academic freedom should be respected. However, for academic integrity to prevail, total autonomy is only achievable through interdependence of all players in the ecosystem. Through transparency, collaboration and engagement, trust and respect are born. Internal and external quality assurance complement each other.

Interpretation, lengthy processes and existence of multiple regulatory bodies

Many institutions report that quality assurance policies, standards, tools, and procedures are complex and difficult to interpret, which results in misunderstandings and varied interpretations and implementation. This creates a need for awareness and extensive capacity building which is resource intensive and costly. The time spent by institutions on preparing accreditation documents and self-evaluation reports is substantial, and therefore diminishes the cost:benefit ratio.

Zimbabwe has witnessed a marked increase in regulatory bodies that require compliance from different angles (academic and professional). These regulatory bodies often work in an uncoordinated fashion, thereby frustrating higher education institutions' effort. Incidents in which ZIMCHE approve degrees and professional bodies disown them and the graduates thereof were reported. An example given was that of medical students who were disowned by the relevant professional body when they had completed 4 years of study and were only left with the final year before housemanship. All but one managed to successfully complete their studies in neighbouring countries. In addition, there are additional costs associated with preparing documents and arranging visits for these regulatory bodies.

Conflicts of interest

A conflict of interest exists when one's private interests are divergent with academic or professional obligations. Experiences revealed that in cases where one has overlapping responsibilities, for example academics who serve as peer reviewers and Vice Chancellors who serve in the ZIMCHE Board, the intertwining of responsibilities poses a threat to academic integrity. There were cases where some ZIMCHE staff revealed that they faced potential compromise in their actions towards certain institutions because of the intentions of securing post-contract or post-retirement jobs at that institution. A conflict of interest may relate to anticipated material gain or loss and can also relate to non-monetary benefits relating to improvements in professional and personal status or access to facilities or classified information.

Assuring quality and academic integrity in Zimbabwe

ZIMCHE positioned itself to support the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education Science and Technology Development deliver an integrated higher education system that brings about convergence, transparency, comparability and consistency. The leadership was achieved through inspiring all players in the higher education system; setting standards; modelling the way; collaborating and capacitating higher education institutions as well as through self-evaluation and continuous improvement.

Inspiration

Considering the potential challenges facing ZIMCHE in its pursuit of quality and taking cognisance of this difficult and important mission, there is need for inspiration. ZIMCHE derived its inspiration and motivation from the works of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry60, described in his book entitled The Wisdom of the Sands:

If you want to build a ship, don't drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.

Thus, extrapolating from the inspiring statement in the context of providing leadership in quality assurance and academic integrity, ZIMCHE's conviction is that:

If you want to build academic integrity, avoid bureaucracy, straightjacketing, stifling innovation and excessive sanctions. Instead, inspire and capacitate all higher education players to yearn for communities of integrity.

During its quality assurance missions, staff from ZIMCHE inspire individuals and institutions using the famous quote from Alan Simpson:

If you have integrity, nothing else matters.

If you don't have integrity, nothing else matters.

Setting standards

The quality assurance framework for ZIMCHE is centred around the processes of registration, accreditation, audits and compliance monitoring. In all these processes, ZIMCHE has embedded the elements of academic integrity by developing support systems, policies, standards and procedures to guide institutions.

ZIMCHE works in close collaboration with relevant academic and professional higher education players to come up with 'agreed' standards of quality assurance in areas of operation and practice. The term 'agreed' reflects the involvement and endorsement of the standards by the key players and the fact that institutions are given these standards and use them for self-evaluation during institutional (internal) quality assurance processes. The standards relate to issues of governance, leadership, academic and support staff, academic grading and promotion, infrastructure, equipment, teaching and learning facilities, minimum bodies of knowledge for each programme, ICT and bandwidth, research, student admission, student assessment, student support, and self-evaluation, among others.

Accreditation is the seal of approval by the external quality assurance agency to assure the public that the higher education institution or programme meets the 'agreed' quality standards and thus can be trusted. The accreditation process involves the use of experts and peers who benchmark with the best practices globally. This makes the process transparent as well as promotes transparency in higher education institutions. Accreditation therefore serves as an effective way of measuring and promoting academic integrity, thereby curbing academic misdemeanors in higher education institutions.

Modelling the way

In modelling the way, ZIMCHE created platforms for information sharing, recognised and rewarded best practices as well as encouraged continuous quality improvement. The voices and experiences, financial, material, intellectual and moral support of colleagues, experts, peer reviewers and partners helped the platforms to be vibrant and productive. ZIMCHE and the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education, Science and Technology Development created an annual platform for information sharing and recognising best practices by individuals and institutions (in all areas of the university mandate) in 2009. This platform was coined the Research and Intellectual Outputs, Science and Technology Development (RIOSET) Expo. Different themes were selected every year, to embrace the prevailing, critical and emerging national imperatives. To showcase the importance of the event, the Expo was graced by its patron, the President of the Republic of Zimbabwe, who delivered the distinguished lecture. In the spirit of sharing and benchmarking, world-renowned academics and professionals also presented and exhibited. Every stakeholder in the higher education fraternity looked forward to RIOSET.

Collaborative and collective approach to engaging all players

ZIMCHE engages all stakeholders and enhances their capacity in academic integrity and other quality assurance matters through running relevant seminars, workshops and conferences aimed at capacity building and discussing pertinent issues. ZIMCHE also guides dialogue through online and physical communication platforms. Through creating opportunities and providing multi-layered support to all stakeholders, ZIMCHE aims to engender a culture of shared responsibility and obligations to academic integrity. Teams hold focus group and targeted discussions with students, academics and management to engage on issues of welfare or any other matter that can affect the quality of the higher education experience. Efforts are made to make representations and find ways of addressing the areas of contention. In addition, ZIMCHE is open to receive complaints, grievances and suggestions on deviant behaviour and on how to address emerging challenges. ZIMCHE, through interactions will all stakeholders, has created an effective ecosystem in which all players work together seamlessly.

Self-evaluation and changing the approach to academic integrity leadership

By way of challenging the process, in 2018 ZIMCHE reviewed its approach to academic integrity leadership through introspection as well as gathering feedback from stakeholders over the 9 years that it had been in existence. ZIMCHE, with support from the African Union, African Quality Assurance Network and the European Union (under the auspices of the Harmonisation of African Higher Education Quality Assurance and Accreditation project), subjected itself to external assessment. The external review, undertaken by international experts who assessed the performance of ZIMCHE as a quality assurance agency, presented a good yardstick to measure performance against best practices in Africa and beyond. The process involved preparation of a self-assessment report by ZIMCHE, interviews of ZIMCHE Board and Secretariat as well as vice chancellors, chairpersons of university councils, academics, peer reviewers, students and indeed all stakeholders.

Regarding academic integrity, the findings showed that the approach that had been in use was largely effective in curtailing incidents of academic dishonesty through accreditation, audits, compliance visits and qualification assessments. All institutions had been requested to establish institutional quality assurance units manned by a Director who would act as the 'local ZIMCHE', and be responsible for ensuring institutional compliance with ZIMCHE standards. Technologies such as anti-plagiarism software became mandatory for all postgraduate and research work. However, stakeholders indicated that the approach was too intrusive, impersonal and sometimes outrightly coercive due to the compliance-driven and rule-based nature of the approach. It therefore became difficult to use it as a basis of developing a culture of academic integrity due to the perception that this approach violates academic freedom and autonomy.

ZIMCHE, being a listening agency, decided to move from the compliance-based approach towards an integrity-based approach. The new approach is premised on remediation and education and is deemed respectful and never shame-based. The approach tries to avoid homogeneity which stifles innovation as well as to avoid bureaucracy, delays or straitjacketing. This approach is hoped to create a culture of continuous self-evaluation at individual and institutional level. The results of these exciting developments are yet to be evaluated. Watch this space!

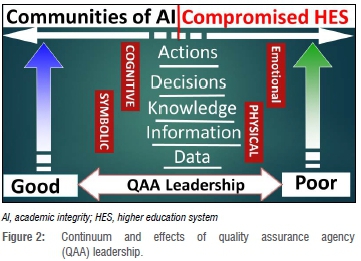

As ZIMCHE undertakes these activities, there is an overwhelming response from stakeholders that it is exhibiting good leadership which improves both quality and academic integrity as illustrated in Figure 2.

Discussion

The challenges of conflicts of interest by members of ZIMCHE Secretariat and Board that might compromise the decisions during quality assurance undertakings are consistent with the challenges reported in existing literature.33 ZIMCHE was, however, able to circumvent their occurrence by taking a leadership role in promoting academic quality and integrity through the ecosystem approach. By setting 'agreed' quality standards collaboratively with all stakeholders and evaluating institutions with the involvement of the internal members, peers and relevant professional bodies, the processes are transparent, and the achievement of trust was made possible. The evaluation processes of registration, accreditation and audits went a long way in promoting academic integrity in line with the assertion by Mckenzie37. This collaboration and engagement created an ecosystem in which all stakeholders are aware of each other's presence, needs, contributions and expectations in sync with similar research results.46 The events and fora for capacity building, dialogue and exposition of good practices by individuals, institutions and stakeholders created vibrant platforms for information sharing integration and promotion of desired behaviours, as expounded in literature.41,42,46

The leadership role taken by ZIMCHE in inspiring and supporting institutions through establishment of institutional quality assurance units was developmental and geared at achieving set goals for academic quality and integrity, as suggested in other studies.34 Engagement of students and staff in institutions, and all stakeholders in various capacities, demonstrated ZIMCHE's capacity to energise, coordinate and synergise all players towards effective goal attainment, as reported in the literature.35,36

The move taken by ZIMCHE to self-introspect and submit its activities for scrutiny by external assessors and stakeholders presents another example of exemplary leadership. It thus becomes possible for institutions to acquire good habits that promote transparency and academic integrity as reported in the literature.47 The fact that ZIMCHE - in spite of already being in the right direction through employing the ecosystem approach - was ready to change its approach in line with review recommendations and literature,48 poises the higher education system to achieve greater academic integrity levels. This is so, despite the assertion that corruption in the wider society will necessarily induce academic dishonesty.

Conclusion

This article highlights the importance of academic integrity and situates quality assurance agencies to play a central role in fostering academic integrity. The case of ZIMCHE showcases how the organisation led by example and assumed an innovative and transformational leadership role in fostering academic integrity through use of the higher education ecosystem approach. Through self-evaluation and incorporating voices of stakeholders, ZIMCHE was able to change its approach from one that relied heavily on compliance, to one that showed greater potential of cultivating a culture of academic integrity. In view of the new higher-level integrity-based approach, there is need to track and evaluate ZIMCHE's progress in this trajectory to academic integrity.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible through the work and insights of all the colleagues at ZIMCHE as well as support from the higher education institutions, the Government of Zimbabwe and all the stakeholders. Appreciation is due to the Council on Higher Education (South Africa) for creating a platform where the research could be presented and critiqued, thus adding value to the manuscript.

References

1.Tauginienė L, Ojsteršek M, Foltýnek T, Marino F, Cosentino M, Gaižauskaitė I, et al. General guidelines for academic integrity. ENAI report 3A [document on the Internet]. c2018 [cited 2019 Jul 31]. Available from: http://www.academicintegrity.eu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/GLOSSARY_final.pdf [ Links ]

2.Bretag T. Academic integrity [document on the Internet]. c2018 [cited 2019 Jul 16]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.147 [ Links ]

3.Fishman T, editor. The fundamental values of academic integrity. 2nd ed. International Center for Academic Integrity, Clemson University; 2014. Available from: https://www.academicintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Fundamental-Values-2014.pdf [ Links ]

4.Anohina-Naumeca A, Tauginienė L, Odineca T. Academic integrity policies of Baltic state-financed universities in online public spaces. Int J Educ Integr. 2018;14, Art. #8, 14 pages. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0031-z [ Links ]

5.Tauginienė L. Embedding academic integrity in public universities. J Acad Ethics. 2016;14(4):327-344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-016-9268-4 [ Links ]

6.Kalnins V. Latvia's anti-corruption policy: Problems and prospects. Riga: Soros Foundation; 2001. [ Links ]

7.Denisova-Schmidt E. Corruption, the lack of academic integrity and other ethical issues in higher education: What can be done within the Bologna process? In: Curaj A, Deca L, Pricopie R, editors. European higher education area: The impact of past and future policies. Cham: Springer; 2018. p. 61-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77407-7_5 [ Links ]

8.Glendinning I, Orim S, King A. Policies and actions of accreditation and quality assurance bodies to counter corruption in higher education. Washington DC: CHEA; 2019. Available from: https://www.chea.org/corruption-higher-education [ Links ]

9.Peytcheva-Forsyth R, Harvey M, Lyubka A. Using a student authentication and authorship checking system as a catalyst for developing an academic integrity culture: A Bulgarian case study. J Acad Ethics. 2019;17(3):245-269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-019-09332-6 [ Links ]

10.Martin M, Stella A. External quality assurance in higher education: Making choices. Paris: UNESCO; 2007. [ Links ]

11.United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). Zimbabwe country profile for 2017. Addis Ababa: UNECA; 2018. [ Links ]

12.Nyoni T. The curse of corruption in Zimbabwe. Int J Adv Res Publ. 2017;1(5):285-291. Available from: http://www.ijarp.org/published-research-papers/nov2017/The-Curse-Of-Corruption-In-Zimbabwe.pdf [ Links ]

13.Choruma A. Corruption stalls Zimbabwe's economic agenda. Financial Gazette. 2017 June 30. [ Links ]

14.Shizha E, Kariwo E. Education and development in Zimbabwe: A social, political and economic analysis. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers; 2011. [ Links ]

15.Garwe E, Thondhlana J. Higher education systems and institutions: Zimbabwe. In: Teixeira P, Shin J, editors. Encyclopedia of international higher education systems and institutions. Dordrecht: Springer; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9553-1_479-1 [ Links ]

16.Garwe EC, Maganga E. Plagiarism by academics in higher education institutions: A case study of the Journal of Zimbabwe Studies. Int Res Educ. 2015;3(1):139-151. https://doi.org/10.5296/ire.v3i1.7060 [ Links ]

17.Gonye J, Mareva R, Dudu WT, Sibanda J. Academic writing challenges at universities in Zimbabwe: A case study of Great Zimbabwe University. Int J English Lit. 2012;3(3):71-83. https://doi.org/10.5897/ijel11.092 [ Links ]

18.Chireshe R. Academic dishonesty: Zimbabwe university lecturers' and students' views. S Afr J High Educ. 2014;28(1):45-59. https://doi.org/10.20853/28-1-325 [ Links ]

19.Díaz-Méndez M, Saren M, Gummesson E. Considering pollution in the higher education (HE) service ecosystem: The role of students' evaluation surveys. The TQM Journal. 2017;29(6):767-782. https://doi.org/10.1108/tqm-03-2017-0031 [ Links ]

20.Macfarlane B, Zhang J, Pun A. Academic integrity: A review of the literature. Stud High Educ. 2014;39(2):339-358. [ Links ]

21.Uzochukwu M. Corruption in Nigeria: Review, causes, effects and solutions [webpage on the Internet]. c2015 [cited 2019 Aug 12]. Available from: https://fbdglobalnews.wordpress.com/2015/..../Corruption-in-Nigeria-review-causes-eff [ Links ]

22.Kranacher MJ. Combatting financial fraud in higher education. In: Global corruption report - Education. London: Routledge; 2013. p. 114-118. [ Links ]

23.Attewell P, Thurston D. Educational imposters and fake degrees. Res Soc Strat Mobil. 2011;29:57-69. [ Links ]

24.Brown GM. Degrees of doubt: Legitimate, real and fake qualifications in a global market. J High Educ Pol Manag. 2006;28(1):71-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800500440789 [ Links ]

25.Chowdhury F. Grade inflation: Causes, consequences and cure. J Educ Learn. 2018;7(6):86-92. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v7n6p86 [ Links ]

26.Zietman AL. Falsification, fabrication and plagiarism: The unholy trinity of scientific writing. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87(2):225-227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.07.004 [ Links ]

27.Strittmatter C, Bratton VK. Teaching plagiarism prevention to college students: An ethics-based approach. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield; 2016. [ Links ]

28.Zhang YH. Against plagiarism: A guide for editors and authors. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. [ Links ]

29.Harvey G. Writing with sources: A guide for Harvard students. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company; 2008. [ Links ]

30.Moodie G. Bureaucratic plagiarism. Plagiary. 2006;1:66-69. [ Links ]

31.Walker J. Student plagiarism in universities: What are we doing about it? High Educ Res Dev. 1998;17(1):89-106. [ Links ]

32.Velliaris DM, Willis CR, Pierce JM. International student perceptions of ethics in a business pathway course. In: Ribeiro FM, Culum B Politis Y, editors. New voices in higher education research and scholarship. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; 2015. p. 234-253. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-7244-4.ch012 [ Links ]

33.Sutton A, Taylor D. Confusion about collusion: Working together and academic integrity. Assess Eval High Educ. 2011;36:831-841. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2010.488797 [ Links ]

34.Hallak J, Poisson M. Corrupt schools, corrupt universities. What can be done? Paris: UNESCO/IIEP; 2007. [ Links ]

35.US Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA). Recognition of accrediting organizations: Policy and procedures. Washington DC: CHEA; 2010. [ Links ]

36.Bennet A, Bennet DH, Lewis J. Leading with the future in mind: Knowledge and emergent leadership. In: Thought leaders: The passion for knowledge. Frost, WV: MQI Press; 2015. [ Links ]

37.Davenport TH, Volpel SC. The rise of knowledge towards attention management. J Knowl Manag. 2001;5(3):212-221. [ Links ]

38.McKenzie A. Academic integrity across the Canadian landscape. Can Perspect Academic Integrity. 2018;1(2):40-45. https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v1i2.54599 [ Links ]

39.Anechiarico F. End-runs and hairy eyeballs: The costs of corruption control in market democracies. Conn J Int Law. 1999;14:379. [ Links ]

40.Cruz CC, Gómez-Mejia LR, Becerra M. Perceptions of benevolence and the design of agency contracts: CEO-TMT Relationships in family firms. Acad Manage J. 2010;53:69-89. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.48036975 [ Links ]

41.Ferguson K, Masur S, Olson L, Ramirez J, Robyn E, Schmaling K. Enhancing the culture of research ethics on university campuses. J Acad Ethics. 2007;5:189-198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-007-9033-9 [ Links ]

42.True G, Alexander LB, Richman KA. Misbehaviors of front-line research personnel and the integrity of community-based research. J Empirical Res Hum Res Ethics. 2011;6(2):3-12. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2011.6.2.3 [ Links ]

43.Segal L. Battling corruption in America's public schools. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2004. [ Links ]

44.Shapiro S. Agency theory. Annu Rev Sociol. 2005;31:263-285. [ Links ]

45.Davis J, Schoorman D, Donaldson L. Towards a stewardship theory of management. Acad Manage Rev. 1997;22:20-47. [ Links ]

46.Alfredo K, Hart H. The university and the responsible conduct of research: Who is responsible for what? Sci Eng Ethics. 2011;17:447-457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-010-9217-3 [ Links ]

47.Aluede O, Omoregie EO, Osa-Edoh GI. Academic dishonesty as a contemporary problem in higher education: How can academic advisers help. Reading Improvement. 2006;43(2):97-106. [ Links ]

48.Willis AJ. Arthur Roy Clapham, 24 May 1904 - 18 December 1990. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 1994;39:72-80. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbm.1994.0005 [ Links ]

49.Aldrich H, Hodgson G, Hull D, Knudsen T, Mokyr J, Vanberg V. In defense of generalized Darwinism. J Evol Econ. 2008;18:577-596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-008-0110-z [ Links ]

50.Lindeman RL. The trophic-dynamic aspect of ecology. Ecology. 1942;23: p. 399. https://doi.org/10.2307/1930126 [ Links ]

51.Banoun A, Dufour L, Andiappan M. Evolution of a service ecosystem: Longitudinal evidence from multiple shared services centers based on the economies of worth framework. J Bus Res. 2016;69(8):2990-2998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.032 [ Links ]

52.Berbegal-Mirabent J, Ribeiro-Soriano DE. Behind league tables and ranking systems: A critical perspective of how university quality is measured. J Serv Theor Pract. 2015;25(3):242-266. https://doi.org/10.1108/jstp-04-2013-0059 [ Links ]

53.Gallant TB. Leveraging institutional integrity for the betterment of education. In: Bretag T, editor. Handbook of academic integrity. Singapore: Springer; 2015. p. 979-993. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_52 [ Links ]

54.Kotter JP. What leaders really do? Harvard Bus Rev. 2001;79(11):85-96. [ Links ]

55.Fogal RE. Designing and managing the fundraising program. In: Herman RD, editor. The Jossey-Bass handbook of nonprofit leadership and management. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley; 2005. p. 419-435. [ Links ]

56.Hamilton ML, Pinnegar S. Intimate scholarship in research: An example from self-study of teaching and teacher education practices methodology. Learning Landscapes. 2014;8(1):153-171. http://www.learninglandscapes.ca/images/documents/ll-no15/mlhamilton.pdf [ Links ]

57.Samaras AP, Roberts L. Flying solo: Teachers take charge of their learning through self-study research. J Staff Develop. 2011;32(5):42-45. [ Links ]

58.Labosky VK. The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In: Loughran JJ, Hamilton ML, LaBoskey VK, Russell T, editors. International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic; 2004. p. 817-969. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6545-3_21 [ Links ]

59.Mitchell C, Weber S. Reinventing ourselves as teachers: Beyond nostalgia. London: Routledge; 2003. [ Links ]

60.De Saint-Exupéry A. The wisdom of the sands. New York: Harcourt; 1950. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Evelyn Garwe

garweec@gmail.com

Received: 15 Mar. 2019

Revised: 12 Sep. 2019

Accepted: 13 Sep. 2019

Published: 27 Nov. 2019

Editor: Hester du Plessis

Funding: None