Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Science

On-line version ISSN 1996-7489

Print version ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.115 n.11-12 Pretoria Nov./Dec. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2019/6326

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Exploring the prevalence of the sexually transmitted marks phenomenon in higher education institutions

Mthuthukisi NcubeI, II

IDepartment of Animal Science, Gwanda State University, Insiza, Zimbabwe

IIInstitute of Development Studies, National University of Science and Technology, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

ABSTRACT

Countries steadfastly pursue academia as a necessary step towards socio-economic development, which places a mandate on institutions of higher learning to stir host-country economies through university deliverables. In Zimbabwe, this entails the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education, Science and Technology Development's 'doctrine' spelling out the philosophy of 'Education 5.0' which emphasises teaching/learning, research, community engagement, innovation, and commercialisation of goods and services. However, academic dishonesty, such as that through 'sexually transmitted marks' (STM), threatens the realisation of such mandates. Although the norm is that such sexual transactions are initiated by academics, evidence shows students also initiate such relationships. Consequently, efforts to eliminate this threat to academic integrity should not only focus on lecturers, but also be extended to students. This paper contributes towards unmasking experiences of STM between male lecturers and female students, female lecturers and male students, and female students and male students, as determined from former university students and university alumni in Bulawayo. Exposing these practices allows for open consultation and adoption of good practices from similar institutions worldwide.

SIGNIFICANCE:

•The majority of respondents all attested to having experienced STM directly or indirectly during their years of study.

•An explicit STM regulation policy targeting all actors across universities is needed

Keywords: power, academic dishonesty, quality, integrity, lecturers, students

Introduction

There is growing interest in issues related to academic integrity, the attribution of which is partly explained by the increasing number of academic fraud cases reported worldwide. This draws from rapid 'massification' and growth of higher education systems that have seen universities become influential organisations in society wherein integrity failures damage institutional brands and the credibility of higher education systems.1,2 Global university branding and related influential international rankings mean positive and negative perceptions of academic integrity can have a significant impact on institutional reputations. Transparency International, a non-governmental organisation working worldwide on matters of corruption, commonly defines corruption as 'the abuse of entrusted power for private gain', adding that in higher education, corruption encompasses 'the lack of academic integrity'1,2. Traditionally, researchers3,4 find that students cheat or exhibit dishonesty in five ways:

•buying a paper from an essay bank or term paper mill;

•copying a whole paper from a source without proper acknowledgement;

•submitting another student's work or a paper written by someone else and passing it off as one's own;

•copying sections of material from one or more sources and deleting the full reference; and

•paraphrasing material from one or more sources without providing appropriate documentation.

However, academic dishonesty can take other forms. This study explored the prevalence of the 'sexually transmitted marks' (STM) phenomenon among institutions of higher learning (IHL) as a facet of academic dishonesty that corrodes academic integrity. The study sought to unmask the deployment of sexual favours to influence outcomes of academic assessments as an increasingly common practice within IHLs. The study scope considered the normative belief that sexual transactions are initiated by lecturers but it is noted that there is also evidence of students initiating such transactions against lecturers. It underscores the importance of focusing not only on lecturers but also on students in efforts to eliminate this threat to academic integrity. The study deployed questionnaires designed to purposively target various university alumni, students, university administrators and lecturers with a view of contributing to the deep-seated phenomenon. Such unmasking potentially uplifts academic integrity and excellence. Furthermore, understanding the social constructions of sexual harassment is a step towards understanding how sexual harassment as a social injustice can be resolved by academics, activists and policymakers alike.1

Statement of the problem

Academic dishonesty is a fundamental issue for the academic integrity of IHL, and one that has lately been gaining increasing media attention.2 Clearly, one of the key roles of IHL is to create an environment conducive to learning - one that will produce highly skilled and technically competent graduates who demonstrate high standards of honesty, ethical responsibility and commitment to serving various professions and society well.3 The growing phenomenon of sexually transmitted marks - a form of transactional lecturer-student sexual relations amounting to academic misconduct and student cheating - directly undermines and negates efforts on this front4-8, piling pressure on academics and institutions to manage it. Witherspoon et al.9 summarise outcomes of lecturer-student cheating into three obvious problems for IHLs. First, it threatens the equity and efficiency of instructional measurement, thus students' relative abilities are not accurately evaluated. Second, cheating students potentially reduce their level of learning, and hence are less prepared for advanced study and application of taught concepts. Last, at the broader, societal level, it is likely that students who disregard academic integrity while at university will treat it with equal disdain in their future professional and personal relationships.

Objectives of the study

1.To determine if the practice of 'sexually transmitted marks' occurs within Bulawayo-based state universities,

2.to highlight the manner in which the salacious relations manifest against integrity, and

3.to explore existing policy documents or regulations that outlaw sexually transmitted marks.

Theoretical framework of analysis: The socio- cultural model

American lawyer and feminist Catherine MacKinnon argues that power is at the core of feminist theories of sexual harassment, although it has rarely been measured directly in terms of workplace authority.10,11 The sociocultural model provides a societal and political explanation that has its roots in MacKinnon's idea that the origins of sexual harassment are a patriarchal society. The model postulates that sexual harassment is a product of culturally legitimate power and status differences between men and women that stand as a manifestation of a wider system of asymmetrical power relations between men and women. For feminist theorists4,10, sexual harassment dovetails gender socialisation processes in which men assert power and dominance over women at work and society. The sociocultural model thus argues that women experience more harassment than men.10

The theory suggests that the patriarchal way in which men occupy power positions in all levels of society, that is, in home and workplace decision-making processes, determines the reproduction of power inequities in the workplace.12-17 Succinctly, the sociocultural model emphasises the role of patriarchy in establishing and maintaining male dominance in society, as a fertile ground for sprouting sexual predators who harass women in IHL. The model is, however, critiqued5,17 for being too simplistic and for not taking into account the sociocultural context that is always shifting. Also, sexual harassment is not a normative behaviour for the majority of men and the sociocultural model does not explain why most men do not harass. The non-conforming attributes are explained4,10 through a conceptual model of the causes and consequences of sexual harassment. Scholars such as Thomas18, Faludi19 and Fitzgerald et al.20 model sexual harassment as a function of two conditions: organisational climate and job gender context20. In their argument, Fitzgerald et al.20 and Lin et al.21 conclude that sexual harassment episodes are positively correlated with the extent to which an organisation 'tolerates sexual harassment' in the workplace, as is the likelihood of working in a male-dominated job context.

Rights-based approaches

Holm22 avows the rights-based approach is the brainchild of the United Nations' Children Education Fund (UNICEF) and ensures the meaningful and systematic inclusion and empowerment of the most vulnerable. Rights-based approaches emphasise that all calamities have perpetrators and victims and advocate for the respect, protection, and fulfilment of the rights of all, including students of IHL. The theory of rights-based development stems from the ethical assumption that all people are entitled to a certain standard in terms of material and spiritual well-being, often taking the side of people who suffer injustice.22 By definition, a rights-based approach to development is a framework that integrates the norms, principles, standards and goals of the international human rights system into the plans and processes of task delivery among IHLs, characterised by methods and activities that link the human rights system and its inherent notion of power and struggle between women and men.17

Rights-based approaches recognise poverty as an injustice and view marginalisation, discrimination and sexual exploitation as human rights violations central to poverty.22 For instance, without a degree, women earn substantially less pay, receive far fewer employee benefits, and are less likely to be financially independent.23 Affected students avoid certain places on campus, change their schedules, and drop classes or activities to avoid sexual harassment, with telling academic effects. Concurring, Jordan et al.24 argue that STM survivors often see their grades drop dramatically, develop post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety, and are frequently left with no opton but to withdraw from classes or extracurriculars to avoid their perpetrators on campus. In a rights-based approach, every injustice is never simply the fault of the individual, as argued by some respondents in the manifestation of sexually transmitted marks in which female students are said to initiate STM relations. However, a rights-based approach also refuses to simply place the burden of injustice and exploitation on abstract notions such as society. For Holm22, human rights claims always have a corresponding duty-bearer; hence a central dynamic of the rights-based approach is identifying root causes of exploitation injustices by empowering rights-holders to claim their rights and enabling duty-bearers to meet their obligations, in this case as per Sexual Harassment Policies.

Academic dishonesty has become an increasingly challenging issue in academic institutions.6,7 Although debatable, scholars6,25 posit that the percentage of academic dishonesty among IHL students is increasing faster in comparison to previous years.

Sexual harassment in all forms is a global issue permeating IHL and workplace fabrics wherein men and women interact.6,7 With respect to universities and other IHLs, Morley and Lussier26 and Taiwo et al.27 argue sexual harassment is not limited to Africa. This harassment has often, albeit silently, taken the form of 'sexually transmitted marks' reported as sexual harassment, which has the effect of harbouring the perpetrators, victims, and the power relations involved therein, and guaranteeing the perpetuation of the salacious relations to the detriment of academic integrity. Acknowledging illicit lecturer-student sexual relations as a global challenge, scholars27,28 propose that the 'sexually transmitted marks' phenomenon deserves mainstreaming into the academic curriculum, particularly to reduce student vulnerability and increase restorative care to victims.

The fact that universities in Ghana and Tanzania have already integrated sexual harassment into course modules on Gender, Power and Sex to address the challenge of male lecturers demanding sex from female students in exchange for higher grades27 bears testimony to the existence of the integrity scourge. Sexual relations between lecturers and students have thus been commodified with 'sex' and 'academic marks' as the 'currency' of trade at the 'academic markets' where the most powerful currency of trade determines the form of reciprocal act by the weaker party at 'this market-place'.

Psychology students in the USA revealed a higher prevalence of sexual harassment and unethical intimacy between postgraduate students and their supervisors than between undergraduate students and their lecturers due to the frequent face-to-face interaction when postgraduates seek advice on their research studies.6 In Africa, tertiary educational institutions in Nigeria have been no exception. For instance, Gaba29 affirms that in Nigeria 'sexually transmitted marks' or 'sex for grades' in the tertiary institutions is a living reality where male lecturers perceive themselves as tin gods and such unprofessional behaviour can be perpetuated unchecked.6,7,27 These views were buttressed in similar studies by Heyneman6 and Taiwo et al.27 who reported a high prevalence of sexual harassment in both educational institutions and the workplace.

The phenonomenon of sexually transmitted marks manifests in various forms, although most importantly it is rooted in unequal power relations that are closely associated with gender-based violence, human rights violation, as well as fraud and corruption.27-29 Students of IHL should be given equal power to match their lecturers in case of violations and being cornered, such that students also get to determine the lecturer's future and tenure. Such a robust anti-academic-corruption policy would instil a sense of confidence in the system and limit the vulnerability of students.

Scholars concur that the harasser often is usually older, powerful and poses something of value that is beneficial to the harassed27-29 and induces 'wilful submission' which is best described as subtle 'sexual coercion'. Such coercion is associated with both sexual bribery and sexual intimidation, which ensnaringly lures the would-be victim of their own volition, thereby camouflaging the practice.27-29

The STM trends reportedly take various forms: from male lecturers to female students, female lecturers to male students, from male students to female students, female students to male students, from male lecturers to female lecturers, female lecturers to male lecturers and non-academic staff, among others. Same-sex relations were not found in a review of STM literature, although they cannot be ruled out. This study did not explore the existence of same-sex relations under STM. STM trends present disturbing scenes in an environment often believed to be a centre of excellence for moulding distinguished leadership skills, high moral qualities and intellectual capacity for human capital and future leadership.27,29

Scholars23,27,29 suggest that, in most cases, female students are most at risk of being victims while male lecturers and 'high-flying' male students are more likely to be the sexual predators, although some studies have arguably presented male lecturers as victims of sexually marauding-predating female students30. Underpinning the 'new trend' of predator students30, Imonikhe et al.31 submit that 'while campus girls always accused lecturers of demanding sex for marks (STM), a survey showed a number of lecturers were actually sexually harassed by female students'.

A study23 of undergraduate college students commissioned by the American Association of University Women Educational Foundation and conducted by Harris Interactive in 2005 found that both male and female students are more likely to be harassed by a man than by a woman. Half of the male students and almost one-third of female students admitted to sexually harassing someone in college. Equal proportions of male and female students say they harassed a student of the other gender.23

This study dispels the notion of female students always being the victims in such transactions and brings to light the downside inherent in transactional sexual engagements 'justified' on the basis of consenting adults. Some studies31-33 have highlighted an increase in cases of sexual harassment, blamed, by the respondents in those studies, on what women wear. Lack of awareness as a causal factor is attributed to many students and academic, administrative and support staff not knowing various university policies and regulations against sexual harassment33, with few having actually read it, translating to the policy evaporation lamented by Longwe34, Risby35 and Macdonald36. These scholars also lamented poor academic monitoring and mentoring systems as creating conducive environments for perpetrators to exploit and harass unabated. While students were generally concerned about the problem of 'missing marks', common in some university units, others preyed on such situations to sexually molest their mentors and lecturers in exchange for higher grades.

The roots of the STM phenomenon are traceable back to the tertiary institutions at which the lecturers were trained7 and at which their lecturers were said to engage in illicit affairs with students. Houreld37 and Tagoe38 opine that sometimes corrupt lecturers entrap their victims by employing different strategies like giving low grades to their targets whom they later invite into their offices. Witch-hunting or marking down assignments of their victims and launching vendettas against those who reject them37,38 are other strategies employed. Teodorescu and Andrei39 highlight that, for example, 17% of students in public universities in Bucharest, Romania's capital, admitted that they had witnessed professors make sexual advances towards students. The problem under such circumstances is that, often, there are no mechanisms in place to check these lecturers' activities, and so victims are not able to talk about it to anyone. When students see these activities going on without anything being done about it, they consider it normal, thus perpetuating the cycle. Consequently, there is always the issue of conflict of interest, bias in the awarding of marks, and betraying a position of trust, hence the need for their registration and de-registration to be guided by ethical standards of professional conduct.

Methodology

As exploring matters of sexual exploitation is obviously a delicate subject, efforts were made by the author to ensure, from the onset, that every respondent would not be identifiable in subsequent published material and presentations. The study involved the collection of university policy documents and a self-administered and postal survey of Bulawayo-based universities in Zimbabwe.

Bulawayo-based universities were purposively selected for convenient access by the researcher. There are 3 universities in Bulawayo and 20 registered universities in Zimbabwe, translating to 15% of the whole university sector in Zimbabwe. This percentage is slightly above Sekaran's40 10% sample representation threshold. Views on STM were, however, drawn from beyond these three universities as the alumni's experiences from former institutions were also taken on board. The questionnaire included questions on whether universities consider STM and exploitation by lecturers or students to be a problem, how it manifests and what universities are doing about it to avoid compromising quality of outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

The study deployed the mail survey design to appeal to a target population stratified according to four strands: lecturers; current postgraduate students; administrators; and alumni of universities in order to get broad-based responses from all key stakeholders and interested parties. This method ensured limited time was effectively and efficiently used by the researcher whose mobility into the target population was limited, and hence would potentially affect the timelines of the research study outcomes.

A total of 30 semi-structured questionnaires eliciting responses to closed-and open-ended questions were distributed through electronic mail to potential respondents comprising alumni from universities in Bulawayo. Email addresses were obtained through cellphone and WhatsApp requests to alumni from universities in Zimbabwe known to the researcher through workplace and academic interactions. Thus, responses do not necessarily represent experiences at any particular university, but span respondents' entire tertiary university experiences.

Analysis

Pre-coded responses in which each response was allocated a value (e.g. '1 for male' and '2 for female'; '1 for yes' and '2 for no') were entered into the Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) program that was used to generate descriptive frequencies to highlight how many within each strata responded in a particular manner.

Results

The main results of the study alongside some of the key emergent themes are presented in this section. All 30 university stakeholders in Zimbabwe responded to the email questionnaires. Results of the study indicate the interactions between university education and STM as an academic fraud that threatens academic integrity. The results are presented as: respondents' demographic information; existence of STM in universities; prevalence of STM; the existence of sexual harassment policies in universities; methods lecturers employ to initiate inappropriate sexual relations with students; the extent to which lecturers initiate lecturer-student sexual relations; the transaction currency used by lecturers and students to initiate illicit sexual relations; and effects of STM on academic integrity.

Demographic information of respondents

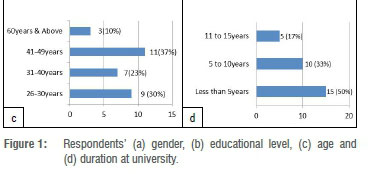

Figure 1a depicts the gender disaggregation of respondents: 53% were women and 47% were men. All female respondents further alluded to having experienced sexual harassment of one form or another during their tenure at university. This finding concurs with others26 that show 68% of female students have been subject to verbal or physical sexual harassment and that nearly one in four has experienced unwanted sexual contact.

Figure 1b shows the educational level of the respondents. Most (53%) respondents had a master's degree, followed by an undergraduate degree (30%), with only 13% holding a PhD and one (3%) a diploma. All female respondents stated that they had been exposed to STM at some point during their university education or employment. This finding gets expression in Gaba29 and Imonikhe et al.31 and in a landmark article by Brandt8 who suggest 50% of all women in the USA at some time or another experience some type of sexual harassment, either in the workplace or in their academic environment.

Figure 1c shows the age range of the respondents, with the highest proportion (37%) being 41-49 years of age; 30% of respondents were 26-30 years, 23% 31-40 years and 10% were 50 or more years old. STM manoeuvres are experienced with each year spent at university. Of the respondents, first degree alumni and administrators expressed exposure to STM in the first 5 years. It was found that the longer the time students and lecturers spend together, the higher the probability of lecturer-student relations sprouting. However, the time taken before female students were exposed to STM for postgraduates was much less. Reconciling the two points to calculated manoeuvres by the STM predators based on knowledge of their target's timeframe on campus. Figure 1d shows the respondent's duration at university - half were at university for less than 5 years.

Existence and prevalence of sexually transmitted marks in universities

All respondents acknowledged the existence of STM in universities and agreed that STM is a concern among IHL and stands as an imminent threat to academic integrity, should it go unchecked.

Although 43% of respondents held the perception that the prevalence of STM was 'not too bad', 33% believed that 'there is a high incidence' and 23% lamented that STM were at 'alarming levels', albeit underreported. Reliance on volunteered data may in this case not be a reliable proxy for STM cases that go unreported for reasons of mutually accruing returns. Witherspoon et al.9 posit that, while sexual harassment is not a new problem and has always been a reality of university life, many would like to pretend it is not happening, preferring instead to live in denial. Although they offered mixed views on the extent or prevalence of STM in Zimbabwe's IHLs, respondents were, however, unanimous that it exists in all IHLs.

Initiators of sexually transmitted marks in universities

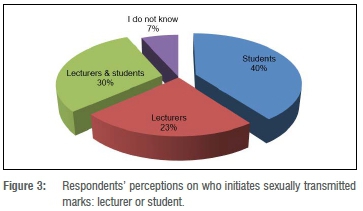

Results shown in Figure 3 further show discordant views on the initiators of STM transactions, with lecturers and students fingered as circumstantial initiators of STM based on the strength of determining currencies of trade, which for the lecturer are the 'higher unearned marks' while for the student the currency of trade is 'sexual favours'.

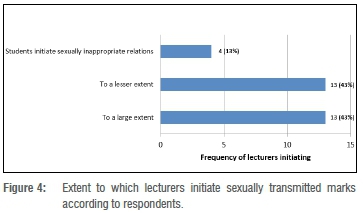

On the extent to which lecturers initiate STM relations and transactions, the results show that lecturers and students have taken equal roles in initiating such transactions (Figure 4) although the literature has sought to portray the transaction as one of unequal standing on power terms.10,11 Borrowing from the late former President Julius Nyerere of the Republic of Tanzania, no equal terms exist in the market-place and the same applies to the notion of STM.

Existence of sexual harassment policies

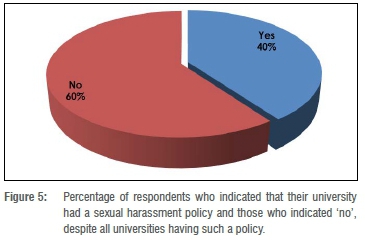

The results in this study which show the existence of a belief that lecturers and students engaged in sexually inappropriate relations are in fact consenting adults in reciprocal relations have not been explored sufficiently.10 Although policies on sexual harassment exist in all the IHLs from which respondents graduated, Figure 5 shows that the existence of these policies was largely unknown to many (60%) former students, although some may have graduated before such policies were put in place.

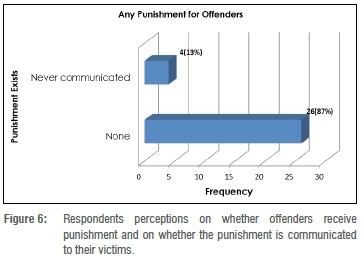

Figure 6 shows that 87% of respondents believe that perpetrators were not punished and 13% stated that the punishment was not communicated. In the rights-based approach, in pursuit of social justice and fulfillment of human rights as well as the promotion thereof, the communication of punishment meted on perpetrators of sexual harassment (including STM) once caught (as is often the case, rather than reported), should be the means to an end to such cases, thus providing closure. On the part of justice, punishment should not only be carried out but should also be seen to be carried out to send a clear message to would-be perpetrators. Rights-holders should feel in control of their circumstances rather than feel vulnerable. Where sexual harassment policies were known to exist, respondents lamented the use of vague and abstract terms not understood by staff and students, making it difficult to enforce. Further, the policies tended to focus on staff-staff sexual relations and paid little if any attention to students as rights-holders and duty-bearers in their own right.

Figure 6 also shows respondents' views regarding punishment meted out to STM offenders. Most (87%) respondents felt nothing was done to offenders despite exposés, hence STM perpetuates. However, others felt punishment was meted out but never communicated to the victim (13%). Neither scenarios help deter future incidents.

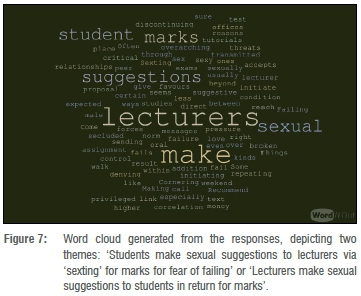

The key themes emergent from the text-based questions of the questionnaire were subjected to wordcloud generation. The resultant wordcloud (Figure 7) depicts two key themes: lecturers and students are equally responsible for STM transactions and thus hold similar responsibilities towards eradicating STM as both potential victims and initiators of such transactions.

Discussion

This study contributes to a budding discourse around STM as a growing form of dishonesty in IHLs. Results show that STM exists in all IHLs in this study in varying degrees and feeds off student vulnerability as lamented by the sociocultural model as a result of power imbalances between women and men in society. Garwe32 cited major reasons given by students as drivers of STM as securing a place at university, awarding of undeserved marks, provision of financial and material support, as well as other favours.

Students cited that a lecturer would ask them to collect assignments from their office instead of returning them at class. Some students would even be victimised by being made to repeat courses if they failed to comply with the demands of the sexual advances of the staff member. Students denoted this practice as 'a thigh for a mark' or sex for grades.31-33

On rights-holders and duty-bearers regarding STM, both were found as equal actors of STM in IHLs. What determined who, between lecturers and students, would initiate was the currency value held by the one and the extent to which another one sought it. This factor underpins the notion of STM as 'transactional sex' whose currency of trade, 'sexual favours' and 'undeserved marks' fluctuates from time to time.

Staff members32,33 argued, 'Some female students blatantly parade parts of their bodies by wearing skimpy clothes thereby exposing themselves to sexual harassment.' This view by staff on causes of STM echoes others32.33 who lament the way female students conduct themselves in terms of behaviour and dressing as influencing their vulnerability to sexual harassment. Rights-based approaches discount sociocultural model perspectives, arguing that such views are irresponsible as every person is responsible for their actions or inactions regardless of the actions of another.

Informed by a rights-based approach core focus area, the study agitates for publicisation of policies and regulations on sexual harassment in IHL. Policies would ensure IHLs respect, protect and fulfil the human rights of lecturers, administrators and students by prohibiting all sexual relations between staff and students in the same educational institution. Strong sentiments emerged from the study: lecturers must be dismissed if found guilty of a sexual relationship with a student at the IHL at which they are employed.

The dismissal should be mandatory, regardless of whether there was consent. Such zero-tolerance policies are consistent with many laws that criminalise adults' sexual relationships based on unequal power. Scholars like Stark10 believe that whether or not university staff are allowed to be in sexual relationships with their students is central to STM. Questions have been raised whether such liaisons between lecturers and students should be viewed as an inevitable result of mature adults meeting and working together or as examples of misuse of power by academics or students? Whatever the stance academics take, what is clear is that questions on salacious relations continue to attract interest and controversy.

Findings: Manifestations of indecent sexual relations against integrity

Qualitative responses from respondents regarding STM effects on academic integrity are shared below:

•Lecturers offer good marks to targeted female students in return for sexual favours. The transaction is preceded by 'sexting' to elicit response as confirmation the lecturer is a willing partner in the academic crime.

•Lecturers give students tough assignments and timelines with personal preferences while students, for fear of failure, seek personal assistance with given tasks.

•Lecturers award female students more marks than deserved against written assignments.

•Lecturers are cornered with writing academic tasks for their partner-female students, earning them higher marks than they would earn thereby.

•Lecturers give tips to female students but withhold such assistance from other students.

•Lecturers negotiate with other lecturers for higher marks on behalf of their STM trading partner (female student), hence STM goes undetected. The lecturer returns the favour for their counterpart to avoid detection.

•Rights-holders deliberately invoke their right to initiate relations whereby females deliberately sit 'strategically badly' in class exposing themselves to seduce lecturers into relationships. However, the rights-based approach contends rights-holders cannot willfully allow their rights to be violated.

•As rights-holders, female students lure lecturers by 'sexting' them, that is, texting sexually suggestive text on WhatsApp and cellphone messages.

•Students visit lecturers in their offices outside normal hours of work, seduce them into sexual contact or sometimes outrightly negotiate sexually transmitted marks as consenting adults.

•University policies on sexual harassment are barely known, do not target lecturer-student sexual relations, which go undetected.

Conclusion

Sexually transmitted marks exist and are pervasive among IHLs in Zimbabwe, albeit in intelligent ways such as 'wilful submission'. This is otherwise best described as subtle 'sexual coercion' and more aggressive uncamouflaged forms.

Sexual harassment policies of IHLs have tended to exclude students as duty-bearers, blindly treating them as only rights-holders. The literature supposes female students are potential STM victims, drawing from skewed patriarchal power imbalances without supposing they could potentially be perpetrators of STM in a transaction-based sexual relationship that easily disempowers male lecturers. However what determines who initiates STM is the strength of the currency of trade on the STM 'market', true to Julius Nyerere's assertions that:

'We are the only people who buy from the prices determined by the seller and sell from prices determined by the buyer.' This means 'no equal terms exist on the market place'.

Although the study found that lecturers and students are equally responsible for STM as perpetrators and victims, the rights-based approach highlights the role subtle and overt power plays in securing coercion that falsely 'presents' students as responsible for STM activities. When students' rights are respected, protected and promoted, the sociocultural dimensions of masculine power vanishes. Thus, even the socioculturally acceptable sexual relations would remain a violation under the right-based approach due to unequal power between the parties.

The spread of STM within IHLs is facilitated by current students socially learning STM behaviours from their lecturers. Alumni's exposure to STM during their learning experiences shape the manner in which they treat their students once employed in IHLs, with an inclination to practice the same STM.

Recommendations

•Duty-bearers like the Government of Zimbabwe; the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education, Science and Technology Development; and the Zimbabwe Council for Higher Education, must enact explicit STM targeted policies and publicise these policies to minimise STM practices in IHLs.

•IHLs must ensure student orientation programmes tackle this sensitive subject by lifting the so-called 'sensitive subject' veil and allowing open debate about it.

•IHLs must monitor staff through CCTV cameras in offices for the protection of both lecturers and students in case of allegations. Lecturers get to refute allegations while students can reinforce allegations using the same CCTV footage as the case may be. However, all legal and operational procedures for CCTV would need to be observed before such an approach is taken to respect, protect and promote the rights of actors, espousing both perpetrators and victims.

•IHLs across Africa can, and should, provide for ethical conduct and professionalisation through registering academics so as to de-register and blacklist those guilty of STM malpractices. Known offenders should never be employed again at IHL.

Relevance to other countries

A number of countries have increasingly raised concerns over compromised academic standards and quality. They highlight academic fraud including examination cheating and falsification of research data and findings to suit predetermined outcomes. This fraud includes STM practice that permeates across cultures, geography and development status. Exposure of the manifestations and effects of STM will induce IHLs to halt and reverse dishonesty concerns that do not discriminate by race, income, size or stature of university.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge various university alumni respondents from across the academe in Bulawayo and constructive criticism from participants in the session 'Threats to Academic Integrity and the Impacts Thereof' (Session Chair: Dr Senoelo Nkhase, Pretoria). This research article is a revised format of a paper presented at this session of the Council on Higher Education (CHE)'s Quality Promotion Conference (Pretoria, South Africa; 26-28 February 2019).

References

1.Larson RW, Wilson S, Brown BB, Furstenberg FF, Verma S. Changes in adolescents' interpersonal experiences: Are they being prepared for adult relationships in the twenty-first century? J Res Adolesc. 2002;12(1):31-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.00024 [ Links ]

2.Bartlett L. Dialogue, knowledge, and teacher-student relations: Freirean pedagogy in theory and practice. Comp Educ Rev. 2005;49(3):344-364. https://doi.org/10.2307/3542209 [ Links ]

3.Camp MD. The power of teacher-student relationships in determining student success [dissertation]. Kansas City, MO: Missouri University; 2011. [ Links ]

4.Altbach PG. The question of corruption in academe. Int High Educ. 2004;34:8-10. [ Links ]

5.Macfarlane B, Zhang J, Pun A. Academic integrity: A review of the literature. Stud High Educ. 2014;39(2):339-358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.709495 [ Links ]

6.Heyneman SP. Higher education institutions: Why they matter and why corruption puts them at risk. In: Sweeney G, Despota K, Lindner S, editors. Global corruption report: Education. London: Transparency International; Earthscan; Routledge; 2013. [ Links ]

7.Denisova-Schmidt E. Corruption, the lack of academic integrity and other ethical issues in higher education: What can be done within the Bologna process? In: Curaj A, Deca L, Pricopie R, editors. European higher education area: The impact of past and future policies. Cham: Springer; 2018. p. 61-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77407-7-5 [ Links ]

8.Brandt DS. Copyright's (not so) little cousin, plagiarism. Comput Lib. 2002;22(5):39-429. [ Links ]

9.Witherspoon M, Maldonado N, Lacey CH. Undergraduates and academic dishonesty. Int J Bus Soc Sci. 2012;3(1):76-86. [ Links ]

10.Stark N. Millennials making meanings: Social constructions of sexual harassment regarding gender and power among Generation Y [master's thesis]. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida; 2015. [ Links ]

11.Brimble M, Stevenson-Clarke P. Perceptions of the prevalence and seriousness of academic dishonesty in Australian universities. Aust Educ Res. 2005;32(3):19-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03216825 [ Links ]

12.Lupton RA, Chapman KJ, Weiss JE. International perspective: A cross-national exploration of business students' attitudes, perceptions, and tendencies toward academic dishonesty. J Educ Bus. 2000;75(4):231-235. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832320009599020 [ Links ]

13.MacKinnon CA. Sexual harassment of working women: A case of sex discrimination. Book, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1979. [ Links ]

14.Stanko EA. Intimate intrusions. Women's experience of male violence. New York: Routledge; 1985. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203521014 [ Links ]

15.Rospenda KM, Richman JA, Nawyn SJ. Doing ppwer: The confluence of gender, race, and class in contrapower sexual harassment. Gender Society. 1998;12(1):40-60. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/190161 [ Links ]

16.Padavic I, Orcutt JD. Perceptions of sexual harassment in the Florida legal system: A comparison of dominance and spillover explanations. Gender Sociol. 1997;11(5):682-698. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124397011005008 [ Links ]

17.Lamesoo K. Social construction of sexual harassment in the post-Soviet context on the example of Estonian nurses. Tartu: Institute of Social Studies, University of Tartu; 2017. [ Links ]

18.Thomas A. Men behaving badly? A psychosocial exploration of the cultural context of sexual harassment. In: Thomas A, Kitzinger C, editors. Sexual harassment: Contemporary feminist perspectives. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997. p. 131-154. https://doi.org/10.1017/s095001709930012x [ Links ]

19.Faludi S. Backlash: The undeclared war against American women. New York: Crown Publishing Group; 1991. [ Links ]

20.Fitzgerald LF, Drasgow F, Hulin CL, Gelfand MJ, Magley VJ. Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. J Appl Psychol. 1997;82:578-589. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.82.4.578 [ Links ]

21.Lin X, Babbitt L, Brown D, Sleigh C. Sexual harassment in the workplace: Theory, evidence and remediation [document on the Internet]. c2016 [cited 2019 Sep 17]. http://conference.iza.org/conference_files/JobQual_2016/brown_d3585.pdf [ Links ]

22.Holm M. Applying a rights-based approach: An inspirational guide for civil society. Copenhagen: The Danish Institute for Human Rights; 2007. [ Links ]

23.Hill C, Silva E. Drawing the line: Sexual harassment on campus. Washington DC: American Association of University Women Educational Foundation; 2005. [ Links ]

24.Jordan CE, Jessica LC, Gregory TS. An exploraton of sexual victmizaton and academic performance among college women. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2014;15(3):191-200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014520637 [ Links ]

25.Jones DRL. Academic dishonesty: Are more students cheating? Bus Commun Q. 2011;74:141-150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569911404059. [ Links ]

26.Morley L, Lussier K. Sex, grades and power: Gender violence in Africa higher education. Cambr J Educ. 2009;41(1):101-115. [ Links ]

27.Taiwo M, Omole O, Omole O. Sexual harassment and psychological consequence among students in higher education institutions in Osun State, Nigeria. Int J Appl Psychol. 2014;4(1):13-18. [ Links ]

28.Schuffer Z. Sexual violence and youth restiveness. In: Introduction to sociology by Dakes (2010). New Delhi: McGraw Hill; 2000. [ Links ]

29.Gaba S. Sexual harassment in Nigeria tertiary institutions. Psychologist. 2010;5(8):319-321. [ Links ]

30.Natukunda C. Makerere lecturers say they are sexually harassed. New Vision. 2008 March 22. Available from: https://wwwnewvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1193825/makerere-lecturers-harassed. [ Links ]

31.Imonikhe J, Aluede OO, Idogho P. A survey of teachers' and students' perception of sexual harassment in tertiary institutions of Edo State, Nigeria. J Asian Soc Sci. 2012;8(1):268-273. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n1p268. [ Links ]

32.Garwe EC. The impact of involving students in managing the quality of higher education provision. J Educ Train Stud. 2015;3(2):51-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/jets.v3i2.672 [ Links ]

33.Oppong C. A high price to pay: For education, subsistence and a place in the job market. Health Transition Rev (Suppl). 1995;5:35-56. [ Links ]

34.Longwe SH. The evaporation of gender policies in the patriarchal cooking pot. Dev Pract. 1997;7(2):148-156. [ Links ]

35.Risby LA. Mainstreaming gender equality: A road to results or a road to nowhere? An Evaluation Synthesis Operations Evaluation Department (OPEV), African Development Bank Group Working Paper; 2011. [ Links ]

36.Macdonald M. Gender inequality and mainstreaming in the policy and practice of the UK Department for International Development. London: Womankind; 2003. [ Links ]

37.Houreld K. Sexual harassment plagues Nigeria's schools. Los Angeles Times. 2007 March 25. Available from: http://www.articles.latimes.com/2007/mar/25/news/adfglecherous25 [ Links ]

38.Tagoe I. Cutting corners: Students' perceived academic corruption at universities in Accra [thesis]. Accra: University of Ghana; 2017. Available from: http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh [ Links ]

39.Teodorescu D, Andrei T. Faculty and peer influence on academic integrity: College cheating in Romania. High Educ. 2009;57(3):267-282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9143-3 [ Links ]

40.Sekaran U. Research methods for business - a skill building approach. 4th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Mthuthukisi Ncube

mthuthukisi.ncube@gsu.ac.zw

Received: 01 May 2019

Revised: 17 Sep. 2019

Accepted: 02 Oct. 2019

Published: 27 Nov. 2019

Funding: None

Editor: Hester du Plessis

Supplementary Material

The data set is available on request from the author.