Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Science

On-line version ISSN 1996-7489

Print version ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.115 n.11-12 Pretoria Nov./Dec. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2019/6323

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Assessment, plagiarism and its effect on academic integrity: Experiences of academics at a university in South Africa

Pryah Mahabeer; Tashmika Pirtheepal

School of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The quality of teaching, learning and assessment is compromised by the growing problem of academic dishonesty, especially in large class sizes as a result of the 'massification' of education. In South Africa and around the world, student plagiarism and cheating has become a matter of concern, especially when it comes to teaching large classes. This concern has received much attention as it impacts negatively on the maintenance of academic standards and integrity at many universities. Academics have a major role to play in the process of maintaining academic integrity. Through an 'interpretivist' and qualitative approach, we explored the experiences of three emerging academics within the Discipline of Curriculum Studies at a university in South Africa. We used Pinar's method of currere as a lens that focuses on academics' experiences of assessment and plagiarism in teaching large classes and its effect on academic integrity. The findings suggest that although 'massification' of education in South Africa is commended for addressing past social injustices and for facilitating accessibility to education, quality teaching and learning including assessment is seriously compromised. This demands a serious rethink of assessment strategies to deter academic dishonesty, and a reconsideration of the way academics and institutions think about plagiarism detection tools in teaching large classes.

SIGNIFICANCE:

•Understanding academics' experiences of assessment and addressing the growing problem of plagiarism can contribute significantly to efforts towards improving teaching and assessment practices in large classes, and to upholding academic honesty within higher education institutions in South Africa.

•A rethink of effective assessment strategies is needed to provide a worthwhile quality educational experience. In the context of this study, ethics within the teacher education curriculum should be prioritised

Keywords: large class teaching, massification, student plagiarism, Turnitin

'Massification' of higher education

A key phenomenon in education worldwide has been 'massification', characterised by high student enrolments and dominated by Neoliberal thinking, with Africa and South Arica being the latest to experience 'massification' which has been applauded in South Africa. Great strides have been made to address and to redress the problems of access to education and the low completion rates of students. Students are eligible to receive quality higher education to prepare them for employment but with the declining level of education fuelled by 'massification', quality cannot be assured.1 The problem is that 'massification' places impossible demands on existing physical, financial and human resources, and universities cannot enrol and address the learning needs of all students desiring to study.1 As a result, contact time with students, and quality assurance, is compromised. We further argue that, with the large numbers of students in the classroom, lecturers are overcome with the volume of assessments to be marked.

In South Africa, studies by the Council on Higher Education2 indicated that of the students entering a 3-year undergraduate programme, less than half drop out, and 50% of students who do enrol take up to 6 years to graduate. Student enrolments rapidly increased by 67% between 2002 and 2014, and by 70% for African enrolments.3 Redress, access, and throughput rates continue to be racially skewed with white completion rates being higher than African student rates.3 The proportion of government funding to universities declined from 49% in 2002 to 40% by 2014.3 Clearly, as a result of increased enrolments and the stagnation of resources and funding, university systems are under substantial pressure with the increasing enrolments, low throughputs, high staff-to-student ratios and an untenable lack of support for funding.3

Massification has initiated changes to the curriculum and large class pedagogies within higher education in South Africa.2 The impact of large class teaching on academics and on academic productivity has not been considered adequately.1 In pursuing an understanding of this impact on developing countries like South Africa, we endeavour to initiate deliberative discussions with academics within the Discipline of Curriculum Studies at a university in South Africa to provide useful insights and find solutions to problems in addressing 'massification' of education, including the matter of teaching large classes and its implications for quality, and the issue of maintenance of academic integrity.

Interplay between assessment, plagiarism, quality and academic integrity

In this section, we conceptualise and draw on the relationships between assessment, plagiarism, quality and academic integrity.

Assessment in higher education

Assessment is undoubtedly important in realising the goals of teaching and learning and in improving student performance, and it cannot be removed from the process of education.4,5 The purpose of assessment in higher education is to: measure the level of student knowledge for quality; assess the extent to which learning outcomes have been achieved; and to judge the quality of higher education institutions and programmes in the upkeep of standards (accreditation).6 With the ever-changing curriculum, the aim of assessment is to measure the teaching and learning process and to guide students to monitor their own learning experiences.5,7

Higher education institutions worldwide are increasingly moving towards online learning management systems to offer effective and efficient assessment solutions to large class teaching and to cope with the demands of the 21st century.8-10 However, in developing countries like South Africa, issues of affordability, access and maintenance of technological software and resources can act as barriers to using technology as a resource to promote quality education.11 Academics play a crucial role in the adoption of and adaptation to the use of technology to enhance quality teaching, learning and assessment practices.12

Suitable assessment design has its roots in student plagiarism prevention.13 Assessment activities that do not engage students in active participation, and those assessments that remain unchanged year after year are not stimulating original thinking, and this influences acts of cheating and plagiarism.14 Research suggests that, although academics in higher education employ numerous assessment practices, the best practices are not usually shared.6

Quality

Universities around the world are committed to respond to the demands of globalisation and 'massification' in higher education, which raises considerable debate around the sustainability of quality education. In response to addressing historical situations, most public universities in South Africa were compelled to enrol students in excess of their capacity, resulting in the 'massification' of education with negative effects on the quality of teaching, learning and assessment.11,15 'Access' and 'quality' are mutually reinforcing and form the foundations for the successful transformation of higher education.16

Within a transformative agenda, the Chinese government had vigorously increased access and provided more opportunities for students in higher education. However, students became dissatisfied and began questioning the effectiveness of massification in higher education in achieving quality and in promoting competitiveness in the job market.17 Clearly, 'massification' has repercussions for quality assurance, as regulating standards and guaranteeing quality becomes problematic in the context of growth and globalisation.1,15

At many universities worldwide, resources, staffing and physical infrastructure have not improved in proportion to increased enrolments, which has impacted negatively on the throughput ratios, graduate employment, increased staff-to-student ratios and the quality of higher education.14,15 Undoubtedly, 'massification' compromises the quality of higher education and discounts, or severely impedes, engagement in the transmission of disciplinary knowledge with negative consequences for appropriate teaching, learning and assessment practices.11,15,18 This scenario further adds to the fear that students are less honest and transparent where cheating and plagiarism might be entrenched.14

Academic integrity: Setting academic honesty and dishonesty apart

Academic integrity upholds and improves the quality of teaching, learning and assessment, while academic dishonesty compromises the quality of teaching and learning processes and undermines the credibility of the student, the academic and the institution.19 Academic integrity in assessment within higher education institutions speaks to the ethical policy and core values of integrity in upholding the goals of the university, in respecting and protecting the knowledge of oneself and others, and in ensuring that all students are guided in the best ethical practice of learning.19

On the other hand, academic dishonesty is the antithesis of academic integrity and it is characterised by different ways in which students are dishonest in their academic practices, such as: plagiarism (stealing the work of others); cheating (taking information for academic credit); collusion; duplicate submission; copying; deceitfulness (lying); conspiracy; misconduct (fabrication, manipulation and misrepresentation of information); and improper use of Internet sources and the computer, including back translation. In South Africa, academic dishonesty poses a serious ethical problem facing students and academics20, with cheating and plagiarism becoming a huge challenge in teaching and assessing large classes and maintaining academic standards of integrity.

As cheating and plagiarism is becoming more pervasive, 'back translation' is the new cyber-based form of plagiarism - a less traceable method of 'cyber-facilitated plagiarism' - to subvert academic integrity, where students intentionally run text through language translation software or through Internet translation software to camouflage the original ideas and ingeniously disguise the source.13 To counter these acts of plagiarism, academics collect a sample of students' language and writing styles at the beginning of a module as a useful way to develop a point of reference, although they recognise that this strategy may be difficult in large classes.13

Student plagiarism in assessment: An ethical concern

Plagiarism is a longstanding, common, worldwide ethical issue facing universities that disrupts learning and the transmission of knowledge.13,20-24 Plagiarism is using the intellectual work of others through means of 'kidnapping' their ideas without the appropriate sources of reference.25 This arguably leads to questioning and the rejection of students' academic work and intelligibility.26

Much of the existing literature speaks to students' perspectives of plagiarism and cheating, and new plagiarism detection strategies.14,21,23 The usual way in which students plagiarise is to 'cut and paste' and blend this into their work.13 Students are concerned that it might occur by accident, and find it problematic when starting out in academia; they indicate being inexperienced and uncertain about referencing and reference incorrectly unknowingly.3 It is important for academics to judge the seriousness of plagiarism and cheating with intentional devious cheating for substantial gain being considered more serious than cheating unintentionally.14 The effect of plagiarism reduces ones' thinking, creativity and originality.13 With the plenitude of electronic journals and literary information readily available, liberal Internet environments support plagiarism and allow students to obtain written papers at a fraction of the time, cost and effort, from writing companies13 - a concept often referred to as ghostwriting24.

Turnitin: Pedagogical or plagiarism detection tool?

Parallel with the uptake of Internet technology is the increase in plagiarism, as more academics complain of plagiarised work submitted for assessment by students.22 As a result, developments made in detecting and deterring student plagiarism have complemented the uptake of Internet technology.13 The accessibility, openness and convenience of the Internet is considered a double-edged sword for students likely to plagiarise; it can similarly be used to commit acts of plagiarism and detect acts of plagiarism.21 Turnitin, SafeAssign and MyDropBox as plagiarism detection strategies claim to deter plagiarism. In spite of these plagiarism detection strategies, grave problems in assessment procedures prevail.24 Arguably these strategies cannot solve plagiarism on its own, and it is still the academics' responsibility to score these assessments and to evaluate the extent of plagiarism which necessitates a systematic approach.22,24 Similarly, Chew et al.27 conclude that it is imperative for academics to decide if the highlighted matched text is legitimate or not within the respective disciplines and institutions.

Turnitin, as a plagiarism detection software, does not actually identify plagiarism. It merely provides a similarity report used to check a student's work for unoriginal pieces of information. Walker24 claims that Turnitin fosters an environment of fear and mistrust amongst students with the presumption that students are guilty until 'proven innocent'. Plagiarism did not decrease as a result of awareness, but increased, and use of Turnitin has not deterred plagiarism.24 This finding raises questions: Why do students still plagiarise despite an awareness of the risks of plagiarism and university policies on plagiarism in place? Why does use of Turnitin not deter plagiarism?

Walker24 interrogated the reliability of Turnitin similarity reports, which undoubtedly saves hours of work for academics in establishing authenticity of work submitted. The disadvantages of Turnitin software are that it does not detect material that is password protected or texts produced by ghostwriting companies.24 Although Turnitin is a strong text-matching instrument, studies suggest it is easy to doctor a document to manipulate the Turnitin plagiarism check.27 Therefore, Walker24 suggests academics approach such reports with caution as they may not always indicate 'genuine plagiarism', accentuating that the responsibility lies with the academic to evaluate the report and to make a decision as to what extent plagiarism has occurred and whether plagiarism was intentional or accidental.

Since the change of outlook on plagiarism detection, it is essential to note the shift in thinking on Turnitin from its role as a plagiarism detection tool to a self-learning tool for students.27 The findings of a study by Chew et al.27 emphasise that Turnitin is not intended to be used as a 'plagiarism detection tool' (policing tool) to punish students for plagiarism but instead it should be used as an effective self-assessment learning tool used to support students. This can be done through the pedagogical use of the Turnitin originality report to improve students' academic writing practice through allowing them the option of multiple submissions. For this approach to be effective, it is suggested that: clear explanations on how to interpret the originality report are needed to thwart misunderstanding and emotional stress and anxiety amongst students; a standardised 'Turnitin policy' be put in place to provide a consistent learning experience for students across an institution; and Turnitin similarity reports should not be the solitary determinant of identifying student plagiarism.27

Factors influencing student plagiarism

Student plagiarism cannot be limited to a particular country, gender, age of students, uptake of technology, education levels of students, students' beliefs about plagiarism and academic honesty, or to the culture and language proficiency of international students.21,22,24 While these factors are recognised, it is acknowledged that many acts of plagiarism go undetected, unreported and unpunished.21

One of the factors limiting ethical learning-oriented assessment practices is the lack of trust, and how distrust can limit assessment development and productive student learning.28 Thus, Carless28 advocates a shift away from 'defensive' assessment. The personal inner drive (desires, needs, ambitions and goals) can also act as a possible threat to integrity because personal desires, needs and ambitions may lure an individual to act only in the interest of oneself, dishonestly.29

Other factors expediting plagiarising and cheating include: students' perception that it is easy to get away with it as universities do 'not chase it up'; different methods of assessment offer different chances for plagiarising and cheating; and students consider cheating is justifiable when teaching and assessments are of poor quality. Importantly, the quality of the student experience is a priority; and lastly, teaching of large classes can result in students feeling neglected and alienated in the system.14

The task of completing writing assessment tasks is complex for students, but ever more perplexing for academics is designing assessment tasks to deter plagiarism and to assess these tasks.22 Prevention of plagiarism might only be possible with the cooperation of colleagues.22 Hence, in this study, we aimed to explore academics' experiences of student plagiarism and its effect on academic integrity within the existing context of teaching large classes intended to cope with the 'massification' of education.

Research methodology

In this qualitative research study, we explored South African academics' experiences to gain an in-depth and subjective understanding of assessment and plagiarism, and its effect on academic integrity in teaching large (undergraduate and/or postgraduate) classes in the Discipline of Curriculum Studies.30,31

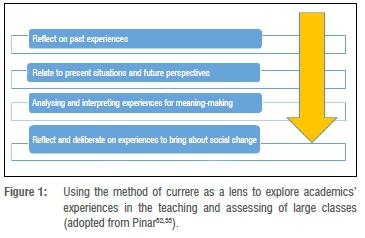

The method of currere, which encompasses four stages, was used to reflect and examine the past and present lived educational experiences and future anticipations of academics.32,33 These include the regressive, progressive, analytical and the 'synthetical' stages. In brief, the regressive stage is the examination of past and present experiences, insights and means of knowing of the academics, which enabled them to share and understand their experiences of teaching and assessing large classes and their experiences of academic dishonesty such as student plagiarism. The progressive stage looked to the future, consciously and deliberately thinking of and imagining the future by challenging and disrupting their own thoughts, which assists the academics on their path to envisioning acts of transformation and committed action. It also looked at the way in which they will teach and assess large classes to promote quality education and academic integrity. The third stage of analysis involved analysing these experiences for meaning-making. The fourth stage, the 'synthetical' moment, returns to the past and present experiences, and future expectations for deeper existential meaning and understanding, which is done through assimilation and interpretation of their experiences and thoughts. As represented in Figure 1, the method of 'currere' provided a methodological lens that brought to the forefront the stories the academics told of their subjective lived experiences for deeper meaning and consistency. They should reflectively recollect their past experiences and reflectively imagine the future as academics in the field of curriculum studies within the context of teaching and assessing large undergraduate classes subsequent to the conception of 'massification' of education.

Context

A 'large class' is defined differently depending on the Discipline and the pedagogical learning situation, resulting in different experiences for academics.11 This study was located in the Discipline of Curriculum Studies in the School of Education at a university in KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. This Discipline offers core compulsory modules to all initial teacher education students at the undergraduate level, with academics teaching classes of more than 300 students, as well as being responsible for coordinating the entire cohort of students for a particular module that often exceeds 1200 students. These student numbers become overwhelming for academics, as expressed in their stories. In light of 'massification' of education, sharing academics' experiences may benefit other academics in the way they think about effective assessment strategies and in how they deliver quality education when confronted with teaching large classes.

Participants

The sampling method utilised was purposive sampling as the participants and sites for study informed the central phenomenon of having experience in assessment, plagiarism and its effect on academic integrity and this was an attempt to ensure that the selection procedure was credible.34-36 At the time of the study, the participants were permanent emerging African academics (lecturers) with not more than 7 years' experience in the Discipline of Curriculum Studies. All three participants (hereinafter referred to as Pearl, Ruby and Tony) were lecturers who had encountered issues with academic dishonesty in the undergraduate and/or postgraduate levels of teaching and were selected to participate based on these experiences, irrespective of race or gender.

Data collection methods

The purpose of the methods used in this study was to make sense of the data collected by showing the interplay between assessment and plagiarism and its effects on academic integrity through the academics' lived experiences of teaching large classes.37,38 In-depth, semi-structured questionnaires and interviews were utilised, as this approach is ideally suited to an epistemological and interpretivist research project.38-40 An interview schedule with open-ended questions allowed the academics to express their experiences, perceptions and opinions openly. The questions were given to the participants beforehand so as to gain a more thought-out, detailed response. The participants were further contacted to clarify information.

For this study, narratives (stories) were constructed from the data collected to explore and understand participants' lived subjective experiences. The narratives were given back to the participants for confirmation.36-38 The stories are reproduced in the supplementary material. The narratives were reflectively and reflexively analysed for emerging themes and for further interpretation and meaning.30,41-44

Issues of trustworthiness and ethical principles were considered in all facets of the study. Gatekeeper Permission was granted to conduct this research (HSS/0727/016). The data were collected from multiple primary sources and pseudonyms were used to guarantee anonymity of the participants so as not to infringe upon their rights in any way.34 The purpose of this study was not to generalise the findings but rather to acquire an understanding of academics' experiences of assessment and plagiarism when teaching large classes.34,44

Discussion of findings

The discussion of the findings was based upon the emerging themes in response to the key research question and sub-questions.

Key research question:

1.What are academics' experiences of teaching and assessing large classes within the Discipline of Curriculum Studies?

Sub-questions:

1.Based on academics' experiences, what are some of the ways in which students displayed academic dishonesty?

2.What measures can academics put in place to diminish academic dishonesty when assessing students in large classes?

The following themes emerged from the data elicited from the participants' stories:

•Class size matters: Academics' experiences of plagiarism in teaching and assessing large classes

•Teaching large classes warrants a rethink of assessment methods

•Efficacy of Turnitin: Teaching or plagiarism policing tool?

•Going beyond the Turnitin report: Factoring in human intervention

•Avoiding plagiarism through assessment design: Hybrid assessments

•Innocent until proven guilty or guilty until proven innocent: Using Turnitin

Class size matters: Academics' experiences of plagiarism in teaching and assessing large classes

Class size matters, especially in teaching large classes. Studies indicated that students in large classes showed less commitment and lower levels of engagement, which make them more prone to cheating and plagiarism.11 Large class sizes correlate with low student performance, goals of education, the educational experiences of teachers and students11, and the demands placed on academics in developing effective teaching experiences45. However, Jawitz45 argued that large class teaching does offer unique prospects for delivering quality learning experiences for students which require the utmost planning, support and expertise. He further opines that academics should challenge dominant taken-for-granted beliefs about large class teaching, and calls for more research on the values of large class teaching. The diversity of students in large classes is a valuable resource to the lecturer. Although literature suggests that there are initiatives in place regarding large class pedagogy, the adequacy of these initiatives needs to be re-evaluated to aid in the university's transformative goals.16

From the narratives, it can be deduced that the academics understand the importance of ensuring a good work ethic for both students and academics in large classes, abiding to university policies and promoting quality teaching and learning. However, the participants revealed that teaching and assessing large undergraduate classes is challenging, frustrating, 'emotionally and psychologically draining' and 'overwhelming' (Pearl). Tony recalled how difficult it is to keep 'student attention and stimulating interaction with non-responsive students' and how 'demanding it is controlling students and maintaining discipline while trying to teach at the same time'.

The emphasis of equity and redress without support for students who come poorly prepared from the school system, has destructive repercussions for the quality of education and the quality of graduates produced in universities.3 This is especially true for the first year of study, for which many students from disadvantaged and rural backgrounds need individualised support to meet their educational needs. Large class teaching does not enable academics to provide sufficient face-to-face contact and support to students because of increased workloads and lack of time and resources to cope with teaching large classes.

Addressing these challenges is crucial to minimising the overload faced by academics, who spend hours developing material and resources for delivery of the lecture and assessments in pursuit of quality teaching and learning experiences. As the 'massification' of students increases at universities, the capacity of academics, resources and infrastructure remain a challenge.1

Within higher education, the aim extends beyond merely acquiring knowledge. It is about solving problems, encouraging students to engage with issues and to think critically. This level of response is fundamental to a deep quality learning experience and clearly class size does affect the quality of teaching and learning.11 Hornsby and Osman11 emphasise that large class sizes fail to enhance higher order cognitive skills, and students show low levels of engagement with the course material, and demonstrate low levels of commitment to and enthusiasm for their work.

Consistent with Hornsby and Osman's finding11, the participants in our study revealed that as enrolments increased with the 'massification' of education, budgeting, staffing, resources and infrastructure did not increase proportionately. The participants in this study complained that they had not received the necessary support from the university to manage large class teaching and assessments. Managing tests for large classes is daunting. We are 'understaffed as invigilators' (Ruby), and students are more prone to cheat and plagiarise in large overcrowded spaces. This situation unquestionably affects the quality of teaching, learning and assessment.

The participants revealed that administering assessments and teaching large classes is challenging and a 'nightmare' (Pearl), hence they found themselves resorting to online assessment strategies, but this also brought about high levels of plagiarism and cheating behaviours. The academics hinted at their roles as academics changing to that of a 'security guard', 'police officer' (Tony), 'investigators' (Pearl) in monitoring and deterring plagiarism.

The participants attributed reasons for student plagiarism as: an 'easy way out' (Pearl), students are 'lazy' and 'lack commitment' and 'accountability', and students feel 'using big words is academic writing' (Tony). Participants indicated that they felt academic writing programmes offered at the university are simply not enough. Literature suggests that some acts of dishonesty occur through conscious choice as a result of laziness and demotivation to study.14 Pearl considers that plagiarism is a result of

Students' poor work ethic and laziness and doing assignments at the last minute, unpreparedness, lack of understanding of assignment requirements and content, and language incompetence…students learn for assessment and not mastery of the content.

Academics' experiences of student dishonesty included: duplicate submissions by students, copying from each other, submission of 'historic assignments' (Tony) from previous years, Turnitin submissions (including curricula vitae of students and texts in isiZulu), the submission of doctored Turnitin originality reports, and 'spin it' (Tony), which is use of an online paraphrasing tool. Tony described students who plagiarise as 'naughty' but that it is an offence committed by the 'best of students'. Pearl lamented how 'students are aggressive and cheat during tests'. The participants further identified various factors influencing student plagiarism such as: the language barrier, students' morals and beliefs, and personal inner drives. These were consistent with some of the factors influencing student plagiarism identified in the literature.21,29

Academics revealed that they only used Turnitin as a plagiarism detection strategy as it is university policy. They agreed that the university policy on plagiarism is 'too lenient' (Tony), and that there are 'no punitive measures in place to deal with this gross misconduct by students' and reports of incidences are not adequately followed up (Pearl). Therefore, they 'no longer bother to report it' (Pearl). The importance and transparency of university policy also places pressure on academic staff to deliver institutionally standard responses to students in certain situations rather than using their personal preference and expert judgement.14 Generally, we found that students at this university are required to sign declarations of academic honesty when submitting assignments that confirm that all sources have been acknowledged. Student handbooks, university policy and official documents outline procedures and implications for what is not acceptable in terms of work submitted. Similarly, it is argued that university regulations place undue pressure on lecturers by demanding a universal response in terms of the university's policy to students who have plagiarised work rather than encouraging personal and professional discretion in finding a solution.14

Two of the participants (Pearl and Tony) expressed concern at the interference of the Student Representative Council as protector of students who commit plagiarism, leaving them reluctant to pursue any transgressions. Academics in this study indicated that they are reluctant to punish and intervene in acts of plagiarism and cheating because of the stress and uneasiness to intervene and punish the offender; the increased workload involved in detecting and punishing the students committing acts of dishonesty; the pressure on academics to sustain pass levels and enrolment figures; and the 'lack of bite' (Pearl) in universities to follow through on offences. Studies revealed that lecturers find themselves hesitant to interfere in situations that involve student plagiarism due to the large amounts of administrative workload and consequences of punishment.13,14 Further studies should explore the reasons why academics are reluctant to take action against those committing acts of academic dishonesty.

Teaching large classes warrants a rethink of assessment methods

Considering the increasing use of the Internet amongst students, it has become the most likely source of plagiarism.22 The participants revealed how 'some students often just copy information from the Internet sources or research papers without proper referencing' (Ruby). Despite the shift in institutional policy to the inclusion of learning management systems such as Moodle in teaching and learning, the participants reported that they find it challenging to accept and to adopt it in their practice and still resort to traditional strategies of assessment to sustain academic integrity as opposed to online assessments. As Ruby commented:

Online quizzes are designed on Moodle, the online teaching site, and is [are] open for a particular period of time for students to be able to engage with it...in the comfort of their home[s]. This form of assessment relieves the stress and pressure of marking large numbers of scripts because the quiz is marked and graded online. The challenge with this form of assessment is that some students may sit together and share the questions and answers; others would take screenshots of the questions and share with their friends.

Many higher education institutions in South Africa are increasingly moving towards technology, such as online learning management systems, to offer effective and efficient assessment solutions to enhance and cope with the demands of pedagogic objectives.8-10 As the demands for technology increase, so do the risks of plagiarism, and academics have a crucial role to play in enhancing quality teaching and assessment.12 Assessment practices must inform and enhance teaching and learning, and it becomes vital that lecturers' reflect on the authenticity of assessment practices.46

The way in which assessments in higher education in South Africa are currently strategised is problematic, and emphasises a lack of assessment practices with a disengagement between teaching, learning and assessment practices.47 Hence, Davids and Waghid47 advocate that assessments should unfold while teaching is taking place and should be purposeful rather than standardised. Within the local context, in developing African countries like South Africa, research related to e-assessment is lacking due to the inability to integrate technology into universities.48 Sarfo and Yidana48 suggest that universities should use a blended learning approach (a combination of online assessment and traditional pen-and-paper assessment) as it is more effective and efficient in developing countries49. In the light of student plagiarism and its effect on academic integrity, academics in this study indicated that they were forced to rethink their assessment strategies in contemporary settings. The participants maintained that technology increased the risks of plagiarism, and so they reverted to traditional forms of assessment such as tests instead of online quizzes, which did not necessarily translate into effective assessment practices.

As the participants revealed, it is not impossible to counter the challenges proffered by 'massification' and teaching and assessing in large classes. It is by focusing on the structure of the curriculum, the strategies employed for instruction (teaching, learning and assessment), and the way students are assessed, that the problems associated with large class teaching environments can be addressed and quality education for all can be achieved.11 Hence, conducive learning environments must be created by academics to maximise the quality of students' educational experiences, and the important roles teaching and assessment strategies play.1

Studies conducted in Lesotho highlight the contradiction between the ever-increasing enrolment at universities and the preparedness of universities to accommodate such 'massification'.1 Academics agree, there is an overwhelming increase in enrolment at universities leading to problematic situations arising such as limited consultation time and an inability to adequately assist students who are struggling. A rethink of pedagogical practices is demanded to ensure that 'massification' of education does not compromise the quality of education.1

Efficacy of Turnitin: Teaching or plagiarism policing tool?

Academics lamented how Turnitin is a perplexing and cumbersome tool for deterring plagiarism in large classes, and how they resorted to alternative forms of assessment to deter student plagiarism. The Turnitin system cannot handle the increased number of submissions, so the administration becomes a 'nightmare' (Pearl). Tony stated that 'Turnitin works for honest students', while Pearl had lost 'trust in the system [Turnitin] because it brings more stress and pressure to find ways that can actually stop [a] student from cheating'. The participants further highlighted that students have 'beaten' (Tony) and 'cheat' (Pearl) the Turnitin system. Turnitin cannot detect if students pay individuals to write their assignments. When plagiarism goes hidden or undetected, the students responsible diminish the work value of honest students, it becomes tiresome at an operational level, and negatively influences the reputation of the university's qualifications.21 Hence the importance of the accuracy of assessments cannot be overemphasised.

The participants indicated that they used Turnitin more as a policing tool and less as a teaching tool. However, Tony and Pearl noted that they do give students a second chance once they have determined the extent to which the student has plagiarised. The participants emphasised that further capacity building is needed to enhance the use of Turnitin. They noted it is 'wasteful expenditure' and 'not useful' (Tony) for undergraduate teaching and assessment. An important concern alluded to by the academics when identifying and determining the extent of student plagiarism, was whether it was committed intentionally or unintentionally.

Good assessment strategies prevent plagiarism. To increase the reliability and efficacy of assessments, academics should plan their assessment tasks, procedures and rubrics very carefully so as to deter plagiarism.22 A practice that concentrates on an 'educative approach' that encourages academics to manage academic dishonesty and includes instruments for deterring and detecting plagiarism when it transpires as opposed to treating it as academic misbehaviour is preferred.19 Academics have a key role to play in the development of student moral understanding and behaviour; however, academics have been found to be unwilling to report or to take action against students who are academically dishonest.23

To manage classroom plagiarism, and perhaps for plagiarism to be eradicated in this ever-progressing digital age, academics need to legalise it for learning purposes by adopting diverse assessment strategies that evade plagiarism and that build a moral student culture.13 Recognising that planning assessments with a vision to 'designing out' can possibly avoid plagiarism and cheating, can assist academics to manage plagiarism and counter back translation, because Turnitin is no longer a deterrent to students who have managed to come up with ways of 'beating' (Pearl) the system.13

Going beyond the Turnitin report: Factoring in human intervention

The participants have lost 'trust' (Pearl) in Turnitin and have a negative attitude toward the use of Turnitin as a plagiarism detection tool, but this has not stopped them from exploring innovative approaches to deal with the matter of plagiarism. 'Turnitin detects similarities but not all similarities are plagiarism' (Ruby). Despite the use of plagiarism detecting software, academics in this study were cognisant of the need to rely on their discretion and not solely on the Turnitin report when detecting plagiarism. They were able to use their judgement in distinguishing between intentional and unintentional plagiarism, hence bringing in the human element in detecting and determining the extent of student plagiarism.22

Avoiding plagiarism through assessment design: Hybrid assessments

Consistent with the findings of Agustina and Raharjo50, academics in this study recognised that many students plagiarise because they are ill-equipped to write academically and there is a language barrier that exists among second-language English students. In providing fair assessment and evaluation, students who 'unintentionally' or 'accidentally' plagiarise because of their incapability to cite and report others' ideas in academic writing should be distinguished from those who intentionally plagiarise.22,24 Hence, academics should focus on these two issues within the curriculum. To assist students, academics acknowledged the importance of including small assessment tasks that can help students learn how to reference and how to paraphrase within the curriculum modules they teach, that is, academic writing skills. The development and acquisition of academic writing skills is one such way to enhance the academic process rather than by solely focusing on plagiarism detection.51

Assessing large classes is a challenge and 'defeats the purpose of why we are assessing and the quality of these assessments' (Pearl). Assessment strategies should be carefully deliberated on, planned and executed to engage the students and to maintain their interest and commitment in promoting academic integrity. Hence, participants in this study advocated that during the teaching and assessing of large classes, it is essential that lecturers carefully consider variations of assessment strategies that are reliable, innovative, realistic, manageable, original and personalised to reduce plagiarism and cheating.

Similarly, Jones and Sheridan13 provide some concrete and pragmatic solutions for academics to consider when thinking about assessment activities to make plagiarising less tempting. The first is 'design it out', which includes good assessment strategy planning in avoiding plagiarism. The second is to move from written assignment submissions to examinations and tests where plagiarising cannot occur. The third is to 'personalise' assessments. This relies on students' own personal experiences which cannot be copied from any external sources. The fourth, 'change', relates to the expansive alteration of assessment tasks for each student cohort so that assessments are not repeated. Lastly, 'restriction' is the limiting of sources of reference, so that the assessor will be well versed with these sources and students will realise that plagiarising is pointless.12 To deter plagiarism, Comas-Forgas and Sureda-Negre52 suggest that the number of assessments should be reduced, hybrid tasks that incorporate theory and practice should be introduced, and regular feedback sessions with students should be arranged to monitor the process of their academic writing. Further, acknowledging that equipping students with the appropriate academic writing skills is a viable preventative measure to plagiarism.25

Innocent until proven guilty or guilty until proven innocent: Using Turnitin

Academics in this study agreed that student plagiarism and cheating is the unethical practice of 'stealing people's ideas and work' (Ruby). They settled on the use of Turnitin as a 'teaching tool' instead of a 'policing tool' that will assist students to enhance their writing and to stimulate their confidence and reduce pressure, anxiety and fear when submitting work for a Turnitin plagiarism tracer test. As Ruby commented, 'Turnitin detects similarities but not all similarities result from plagiarism', that is, similarities detected included common phrases, names and concepts. Tony and Ruby elaborated on how, through using Turnitin as a teaching tool, they gave students a 'second opportunity' (Tony) to 'resubmit the assessment task' (Ruby). Carless28 advocates that lecturers should be given greater autonomy to act responsibly in the processes of teaching and assessment that speak to the principles of sound academic integrity. Nonetheless, Elias20 concluded that academics should stop accepting excuses of pressures and inabilities, as students are using unethical ways of simply wanting to pass and achieve the degree and not pursue knowledge.

In enhancing academic integrity, the academics in this study advocated for: a fully functional academic writing centre; a more collaborative and concerted effort with management and the Student Representative Council; and educational programmes for students that foster good ethical behaviour, accountability and acceptable academic practice. Academics should be innovative in adopting more suitable methods to enhance the quality of their teaching through 'hybrid' assessment tasks that are free of plagiarism and easier to manage. Basic academic writing skills should be taught and tested creatively in conjunction with the teaching of the module.

The findings point to the transmission of easily understandable information and vibrant awareness of cheating and plagiarism, accentuating the positives of good academic practice supported by concrete practical examples.14 Studies suggest that compelling students to sign a pledge (a code of honour) creates awareness and commits them to academic integrity and understanding the consequences of failure to comply with this rule.21 Changing students' mindsets on learning, assessment and plagiarism is vital to sustaining academic integrity. Academics in this study believed that plagiarism is a moral and ethical issue, and that students should be educated on ethics and academic integrity and should be made aware of the implications of fraudulent behaviour. Universities must show that they 'mean business' with a 'zero tolerance' approach; stricter measures should be put in place to monitor and control academic dishonesty.

While there are strategies in place to maintain academic integrity, trust and honesty remain key, and in the ever-changing digital context there will always be new ways to plagiarise. Therefore, it becomes imperative to revisit the dominant approaches in managing plagiarism and cheating in large classroom contexts. Plagiarism and cheating should be managed institutionally, and academics should elect to directly sanction students on the basis of learning instead of outlawing students.13

Martin Trow53 suggested ways of thinking about the development of higher education in progressive societies, accentuating growth, democratisation and diversification. He enunciates the obligation for universities to monitor continuously and to evaluate higher education to guarantee quality. Arguably, the principles of the theory are largely germane to developed countries.1 In institutions of mass education, education becomes more integrated, thus allowing for flexible combinations of courses, and the rejection of academic forms, structures and standards extends to examinations and assessments.53 As such, these further recommendations are put forward: (1) At the university level, operational practices, facilities, resources, and the capacity-building of academics need a rethink to guarantee quality higher education and to provide the necessary attention and support for those students who need it most. This applies especially to first-year students coming from disadvantaged and rural backgrounds. (2) To address the challenges of 'massification', traditional pedagogical approaches need a rethink to include innovative alternatives using technology to reduce overcrowding and to sustain quality in education. Jawitz45 encourages lecturers to develop innovative pedagogies to facilitate effective large class teaching and assessment. This approach should be applauded. Universities have already commenced using online learning management systems such as Moodle and Blackboard, online courses, and 'virtual delivery' to reach large numbers of students without face-to-face contact in the class.45 (3) The apparent disconnection between government, the university and academics should be confronted. Academics need to be given a voice. What is needed is vigorous participation and engagement with all stakeholders at all levels to deal with large class teaching, and its implications for the curriculum and for pedagogical approaches that matter. (4) The overload on academics needs to be addressed by universities to ensure quality education and to avert teachers being pressurised and experiencing burnout, stress and frustration.1 (5) Emerging academics need: relevant educational expertise, sufficient resources and support from the university, and mentoring from skilled senior academics to improve their pedagogical practices in teaching large classes.45

Concluding comments

Teaching large classes is undoubtedly a daunting task with academics experiencing high levels of student academic dishonesty. Academics agreed that academic dishonesty in large classes compromised the teaching and learning process and negatively impacted on the quality of graduates produced, and on the reputation of students, academics and institutions. This situation has influenced the way academics deliberate on their methods of teaching and assessment. Although there is a university policy in place to address plagiarism, academics' felt that this policy is too lenient, and acts of plagiarism reported are not adequately monitored.

This research study prompts academics to think beyond taken-for-granted teaching and assessment strategies in large class situations to perpetuate quality education and academic integrity in warranting a relevant and meaningful educational experience.

Within the context of this study, ethics within the teacher education curriculum are fading and should be prioritised, with a focus on the professional ethics perspective and on ethics education, which is to initiate and prepare future professionals to operate in a shared community of practice that clarifies what it means to act in an ethical, principled and responsible manner, both as a student teacher and as a professional teacher.51

The capacity building of academics with the use of Turnitin and the issues academics face with student plagiarism needs further investigation. Further studies on assessment, plagiarism and its effect on academic integrity can probe into students' experiences of being taught in large classes and their perspectives of pedagogical approaches in the classroom. This will facilitate the analysis of plagiarism and its drivers in universities by allowing student voices to surface.

Authors' contributions

Both authors contributed to the writing of the narratives and the text, and the analysis of the data. P.M. conceptualised the study. T.P compiled the supplementary material.

References

1.Tlali N, Mukurunge T, Bhila T. Examining the implications of massification of education on quality assurance and assessment in higher institutions in Lesotho. Int J Trend Scic Res Develop. 2019;3(3):1561-1568. https://doi.org/10.31142/ijtsrd23493 [ Links ]

2.Council on Higher Education (CHE). A proposed undergraduate curriculum reform in South Africa: The case for a flexible curriculum structure. Pretoria: CHE; 2019. [ Links ]

3.Motala S. Achieving 'free education' for the poor: A realisable goal in 2018? Introduction Part III. J Educ. 2017;68:15-29. [ Links ]

4.Brown G. Assessment: A guide for lecturers. York: LTSN Generic Centre; 2001. [ Links ]

5.Gardner J, editor. Assessment and learning. London: SAGE; 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446250808 [ Links ]

6.Mokhtar R, Rahman AA, Othman SH. An assessment-based metamodel towards a best practice assessment model in higher education. Indian J Sci Technol. 2016;9(34):1-11. https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i34/100825 [ Links ]

7.Shepard LA. The role of classroom assessment in teaching and learning. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado at Boulder; 2001. Available from: https://nepc.colorado.edu/sites/default/files/publications/TECH517.pdf [ Links ]

8.Gikandi JW, Morrow D, Davis NE. Online formative assessment in higher education: A review of the literature. Comput Educ. 2011;57(4):2333-2351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.06.004 [ Links ]

9.Gleason J. Using technology-assisted instruction and assessment to reduce the effect of class size on student outcomes in undergraduate mathematics courses. Coll Teach. 2012;60(3):87-94. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2011.637249 [ Links ]

10.Machado M, Tao E. Blackboard vs. Moodle: Comparing user experience of learning management systems. In: 37th Annual Frontiers in Education Conference - Global Engineering: Knowledge Without Borders, Opportunities Without Passports; 2007 October 10; Milwaukee, WI, USA. https://doi.org/10.1109/fie.2007.4417910 [ Links ]

11.Hornsby DJ, Osman R. Massification in higher education: Large classes and student learning. High Educ. 2014;67(6):711-719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9733-1 [ Links ]

12.Fajet W, Bello M, Leftwich SA, Mesler JL, Shaver AN. Pre-service teachers' perceptions in beginning education classes. Teach Teach Educ. 2005;21(6):717-727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.002 [ Links ]

13.Jones M, Sheridan L. Back translation: An emerging sophisticated cyber strategy to subvert advances in 'digital age' plagiarism detection and prevention. Assess Eval High Educ. 2015;40(5):712-724. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.950553 [ Links ]

14.Ashworth P, Bannister P, Thorne P. Students on the Qualitative Research Methods Course Unit. Guilty in whose eyes? University students' perceptions of cheating and plagiarism in academic work and assessment. Stud High Educ. 1997; 22(2):187-203. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079712331381034 [ Links ]

15.Mohamedbhai G. Massification in higher education institutions in Africa: Causes, consequences and responses. Int J Afr High Educ. 2014;1(1):59-83. https://doi.org/10.6017/ijahe.v1i1.5644 [ Links ]

16.Akoojee S, Nkomo M. Access and quality in South African higher education: The twin challenges of transformation. S Afr J High Educ. 2007;21(3):385-399. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajhe.v21i3.25712 [ Links ]

17.Mok KH, Jiang J. Massification of higher education: Challenges for admissions and graduate employment in China. In: Mok KH, editor. Managing international connectivity, diversity of learning and changing labour markets. Singapore: Springer; 2017. p. 219-243. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1736-0_13 [ Links ]

18.Ntim S. Massification in Ghanaian higher education: Implications for pedagogical quality, equity control and assessment. Int Res High Educ. 2016;1(1):160-169. https://doi.org/10.5430/irhe.v1n1p160 [ Links ]

19.Mulcahy S, Goodacre C. Opening Pandora's box of academic integrity: Using plagiarism detection software. In: Proceedings of the 21st ASCILITE Conference; 2004 December 5-8; Perth, Australia. p. 688-696. Available from: http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/perth04/procs/mulcahy.html [ Links ]

20.Elias RZ. The impact of anti-intellectualism attitudes and academic self-efficacy on business students' perceptions of cheating. J Bus Ethics. 2009;86(2):199-209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9843-8 [ Links ]

21.Jiang H, Emmerton L, McKauge L. Academic integrity and plagiarism: A review of the influences and risk situations for health students. High Educ Res Develop. 2013;32(3):369-380. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.687362 [ Links ]

22.Razi S. Development of a rubric to assess academic writing incorporating plagiarism detectors. SAGE Open. 2015;5(2):1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2158244015590162 [ Links ]

23.Thomas A, De Bruin GP. Plagiarism in South African management journals. S Afr J Sci. 2015;111(1/2), Art. #2014-0017, 3 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2015/20140017 [ Links ]

24.Walker J. Measuring plagiarism: Researching what students do, not what they say they do. Stud High Educ. 2010 Feb 1; 35(1):41-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902912994 [ Links ]

25.Sutherland Smith W. Plagiarism, the Internet, and student learning: Improving academic integrity. New York: Routledge; 2008. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203928370 [ Links ]

26.Pecorari D. Academic writing and plagiarism: A linguistic analysis. London: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2008. [ Links ]

27.Chew E, Lin Ding S, Rowell G. Changing attitudes in learning and assessment: Cast-off 'plagiarism detection' and cast-on self-service assessment for learning. Innov Educ Teach Int. 2015;52(5):454-463. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.832633 [ Links ]

28.Carless D. Trust, distrust and their impact on assessment reform. Assess Eval High Educ. 2009;34(1):79-89. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930801895786 [ Links ]

29.Barnard A, Schurink W, De Beer M. A conceptual framework of integrity. S Afr J Ind Psychol. 2008;34(2):40-49. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v34i2.427 [ Links ]

30.Leedy PD, Omrod JE. Practical research: Planning and design. 9th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2010. [ Links ]

31.Rubin A, Babbie ER. Empowerment series: Research methods for social work. City: Cengage Learning; 2016. [ Links ]

32.Pinar WF. What is curriculum theory? New York: Routledge; 2004. [ Links ]

33.Pinar WF. What is curriculum theory? New York: Routledge; 2012. [ Links ]

34.Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research methods in education. 6th ed. Abingdon: Routledge; 2007. [ Links ]

35.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2007. [ Links ]

36.Creswell JW. Editorial: Mapping the field of mixed methods research. J Mixed Methods Res. 2009;3(2):95-108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689808330883 [ Links ]

37.Giorgi A. Phenomenology and psychological research. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press; 1985. [ Links ]

38.Kvale S. Interviews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 1996. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1098-2140(99)80208-2 [ Links ]

39.Charmaz K, Belgrave LL. Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. In: Gubrium JF, Holstein JA, Marvasti AB, McKinney KD, editors. SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2012. p. 347-365. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452218403.n25 [ Links ]

40.Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 1995. [ Links ]

41.Bell JS. Narrative inquiry: More than just telling stories. TESOL Q. 2002;36(2):207-213. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588331 [ Links ]

42.Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2013. [ Links ]

43.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research method. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1990. [ Links ]

44.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1985. [ Links ]

45.Jawitz J. The challenge of teaching large classes in higher education in South Africa: A battle to be waged outside the classroom. In: Hornsby DJ, Osman R, De Matos-Ala J, editors. Large-class pedagogy - Interdisciplinary perspectives for quality higher education. Stellenbosch: SUN MeDIA; 2013. p. 137-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/9780992180690/09 [ Links ]

46.Scalise K, Wilson M. The nature of assessment systems to support effective use of evidence through technology. E-Learning Digital Media. 2011;8(2):121-132. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2011.8.2.121 [ Links ]

47.Davids N, Waghid Y. University tests should be part and parcel of teaching - not stand-alone events. The Conversation. 2017 June 05; Education. Available from: https://theconversation.com/university-tests-should-be-part-and-parcel-of-teaching-not-stand-alone-events-78481 [ Links ]

48.Sarfo FK, Yidana I. University lecturers experience in the design and use of MOODLE and blended learning environments. Online J New Horizons Educ. 2016;6(2):143-154. Available from: http://www.tojned.net/journals/tojned/volumes/tojned-volume06-i02.pdf#page=150 [ Links ]

49.Baleni ZG. Online formative assessment in higher education: Its pros and cons. Electr J e-Learning. 2015;13(4):228-236. Available from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1062122 [ Links ]

50.Agustina R, Raharjo P. Exploring plagiarism into perspectives of Indonesian academics and students. J Educ Learn. 2017;11(3):262-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.11591/edulearn.v11i3.5828 [ Links ]

51.Maxwell B, Schwimmer M. Professional ethics education for future teachers: A narrative review of the scholarly writings. J Moral Educ. 2016;45(3):354-371. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2016.1204271 [ Links ]

52.Comas-Forgas R, Sureda-Negre J. Academic plagiarism: Explanatory factors from students' perspective. J Acad Ethics. 2010;8(3):217-232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-010-9121-0 [ Links ]

53.Trow M. Problems in the transition from elite to mass higher education. Berkeley, CA: Carnegie Commission on Higher Education; 1973. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Pryah Mahabeer

mahabeerp3@ukzn.ac.za

Received: 02 May 2019

Revised: 16 Sep. 2019

Accepted: 04 Oct. 2019

Published: 27 Nov. 2019

Editor: Hester du Plessis

Funding: None

Supplementary Material

The supplementary file is available in pdf: [Supplementary file]