Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Science

On-line version ISSN 1996-7489

Print version ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.115 n.5-6 Pretoria May./Jun. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2019/a0310

BOOK REVIEWS

Tracing the origins of South African constitutionalism

Alice L. Brown

African Centre for the Study of the United States, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

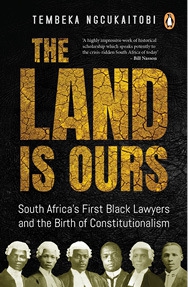

BOOK TITLE: The land is ours: South Africa's first black lawyers and the birth of constitutionalism

AUTHOR: Tembeka Ngcukaitobi

ISBN: 9781776092857 (print); 9781776092864 (ebook)

PUBLISHER: Penguin Random House, Cape Town; ZAR290

PUBLISHED: 2018

In this comprehensive and eloquent account of South Africa's first black lawyers and activists and the essential role they played in the struggle against racial oppression, Advocate Ngcukaitobi illuminates histories that have gone woefully unrecognised and underappreciated. Alfred Mangena, Charlotte Maxeke, Alice Kinloch, Richard Msimang and Pixley ka Isaka Seme are some of the trailblazers whose stories are chronicled in this impressive volume.

Some of the names, such as Seme, we have known in the context of the history of the formative years of the African National Congress. I suspect, however, that many of us were not aware of the parts these individuals, and others, played as legal practitioners and strategists who attempted to use law and litigation to challenge the copious violations perpetuated against black South Africans by the British colonists and the Afrikaner nationalists alike. Indeed, it appears that, until this volume, there has been insufficient recognition of these pioneering black legal intellectuals and practitioners who 'fought the good fight' in the face of tremendous obstacles and barriers. Ngcukaitobi has done us a great service by uncovering and resuscitating these histories and narratives.

He introduces us to the achievements and failures of these individuals, on personal and professional fronts, in addition to the political and legal battles waged against the British and Afrikaner authorities and the in-fighting that took place within the ranks of their organisations. In the context of their careers, some were denied the opportunity to practise their trade while others, who were allowed to represent clients in court, were often discriminated against by their white peers and denied access to professional bodies. They were plagued by a multitude of problems that included, amongst others, an inability to sustain financially their practices and the tendency to over-extend and over-commit. Indeed, Ngcukaitobi provides a holistic picture of these multidimensional personalities, which includes their dedication to the fight for the humanity and dignity of black South Africans while at times simultaneously holding elitist, condescending and paternalistic attitudes towards their uneducated brethren.

In telling these narratives, Ngcukaitobi also highlights the intersections and connections between South Africans and the African diaspora at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries. In particular, the reader is introduced to the interlocking histories of the black, educated elite of South Africa and African America: among other things, that a number of South Africans were educated in the USA at institutions that included Wilberforce University, Hampton Institute and Lincoln University, places of higher education that were established to provide training and education to ex-slaves. Further, we learn of the Trinidadian Henry Sylvester Williams - crusader, advocate and founder of Pan Africanism - his sojourns in England and South Africa and the manner in which he and South Africans like Alice Kinloch and J.T. Jabavu and African Americans such as W.E.B. du Bois, amongst others, met and collectively strategised with regard to combating racism and uplifting black people across geographic boundaries. These accounts make for fascinating and intriguing historiography.

Moreover, Ngcukaitobi offers insightful accounts of some of the first strategic impact litigation to be carried out in South Africa. Here, the reader learns that this type of legal practice did not begin in the late 1970s and early 1980s with the establishment of public interest law centres such as the Legal Resources Centre, the Centre for Applied Legal Studies and the Black Lawyers Association Legal Education Centre. Rather, it began in the early 1900s with efforts of Williams, Mangena, Seme and others. Although many of the cases brought were unsuccessful, these activist legal practitioners attempted to use the law to promote equality, and sometimes they succeeded. In a context in which law was used to subjugate and deny, they tried to use it as an instrument to remedy violations of fundamental human rights.

Although I appreciate and admire the thoroughness of this presentation, there were times during my reading when I felt overwhelmed by the detail and I noticed some repetition. In these instances, I thought that the volume could have benefitted from closer editing. Take, for example, when Ngcukaitobi provides an account of the rugby prowess of Richard Msimang or the comprehensive list of all the areas of law in which he was examined or the exhaustive report of Seme's years in the UK. Was this information crucial in providing the reader with an understanding and appreciation of the influence and contributions of these early crusaders for equality and human rights? I wonder.

In the big picture, however, these are minor criticisms. On the whole, this book does a noteworthy job on a number of fronts. It gives voice to individuals who have been ignored or written out of the mainstream historical narratives, and of special note is the attention paid to female activists such as Alice Kinloch and Charlotte Maxeke. It focuses attention on the ways that, in the early 20th century, black legal practitioners attempted to use law and litigation to challenge racial discrimination and exploitation. Further, through its careful and meticulous presentation, it traces the history and documentation of land dispossession that occurred during the late 19th and the first 40-odd years of the 20th centuries. In the context of current debates surrounding land reform and land redistribution, The Land is Ours provides a timely evidentiary record of the deliberate and violative removal and dispossession of black South Africans from the land.

Accordingly, I would highly recommend this volume not only to legal practitioners, historians, other social scientists, policymakers and analysts, but to anyone interested in learning and understanding more about the rich, and under-told, histories of the men, and women, who scattered barriers and engaged in some of the first legal battles against racial oppression in South Africa. By taking on this fight, these black intellectuals and legal practitioners planted the conceptual seeds of a bill of rights and constitutionalism that germinated over the course of the 20th century and came to fruition, at least in part, during the 1990s.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Alice Brown

Email: brown.alice99@gmail.com

PUBLISHED: 29 May 2019