Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Science

On-line version ISSN 1996-7489

Print version ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.114 n.11-12 Pretoria Nov./Dec. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2018/a0294

INVITED COMMENTARY

Reducing inequality and carbon emissions: Innovation of developmental pathways

Harald Winkler

Energy Research Centre, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Professor Harald Winkler is the recipient of the 2017/2018 NSTF-South32 Special Annual Theme Award: Sustainable Energy for All (in recognition of the United Nations 'International Decade of Sustainable Energy for All').

Keywords: inequality; climate change; mitigation; development; sustainability

Dual challenges of inequality and mitigation

Inequality and poverty are the top priorities in South Africa's National Development Plan1; job creation and education are key means to reduce both. At the same time, the country wants to make a fair contribution to global efforts to combat climate change. In 2015, the global community adopted both Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)2 and the Paris Agreement3. To understand what it is to be human in the 21st century, and particularly in South Africa, one needs to consider high inequality2,4 and dangerous climate change3,5. Beyond analysis, the challenge is to reduce inequality and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions - which is the motivation for this article. To achieve that, innovative pathways to development will have to be charted. In this respect, local is the new global and we 'need to bury the notion that global is not African'6. This article starts with a South African focus, considered integral to global challenges of inequality and mitigation.

Inequality and mitigation, locally and globally

Consider inequality in South Africa. Inequality has many dimensions, but while Thomas Pikkety argues compellingly that asset inequality is more persistent than income inequality7, the latter is the more common measure, including in South Africa. Figure 1a illustrates a notional household of five people - one might think that with a monthly income of ZAR50 000, this household would be solidly in the middle of the South African distribution. However, the actual position is the green line, whilst the median value is shown by the small red line. This observation is underpinned by the robust overall finding of a review of the economics of income inequality: 'that inequality in incomes is extremely high from a global comparative perspective and has increased since the democratic transition in 1994'8.

Income inequality is a persistent feature globally. While the world is no longer divided into two groups of developed and developing countries, it is also not homogeneous (see http://www.ecomagination.com/hans-rosling-and-the-future-of-the-world; or watch Rosling's brilliant talk at http://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_and_the_magic_washing_machine.html). Figure 1b shows a spectrum of income distributions by ventile, or twentieth of the population. Milanovic9 shows that the poorest 5% of Americans have the same income as the richest 5% of Indians - about USD3000-4000 per month.

Further research is needed into such distributions by wealth or assets, and more work is needed to provide a view of inequality of GHG emissions across households. The trade-off between affluence and household emissions has been analysed for Indonesia,10 with similar work being initiated in South Africa. At this stage, we cannot show comparable graphs of inequality by GHG emissions across income groups. What we do know is that inequality in access to energy services is a critical factor in (South) Africa and across countries.11

The inequality of global energy CO2 emissions compared to poverty are illustrated in Figure 2. Country areas are adjusted for cumulative emissions, since 1850 in Figure 2a. A radically different map is generated in Figure 2b, which maps current levels of poverty.

It is a deep injustice that those less responsible for the problem of climate change are most vulnerable to its impacts. Not only do poor countries and communities have lower capacity to adapt, or recover from loss and damage, but they are expected to take on some burden of reducing emissions in future.13,14 What is needed is not only zero poverty, zero carbon - but also zero impacts. The coping capacity across African countries is a major concern.15

There is a very wide range of possible interactions between scholars who investigate poverty and inequality and the climate change community of practice. The focus in this commentary is on mitigation within climate change (distinct from physical science, and impacts, vulnerability and adaptation), and on inequality as a focus that sharpens the focus on poverty.

The focus on mitigation is partly because it is the author's research interest, but more fundamentally because GHG emissions are the root cause of climate change. After 17 years of assessment, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that warming of the climate system is 'unequivocal' and 'very likely due to anthropogenic GHG emissions'16. Reducing GHG emissions goes to the root of the problem, and in that sense is a radical solution. To address both inequality and mitigation is to ask some fundamental questions.

The challenges of development and climate are being considered globally. Figure 3 shows the SDGs, highlighting Goal 1 to 'end poverty in all its forms everywhere', Goal 10 to 'reduce inequality within and among countries', and Goal 13 to 'take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts'2. The triangle linking the three goals is the focus of this article.

The Paris Agreement represents the best, if imperfect, efforts of the global community to respond to climate change. It is considered a hybrid architecture, including bottom-up and top-down elements.17,18 Probably the most significantly new elements are nationally determined contributions (NDCs), with countries deciding what to commit to rather than establishing that in a multi-lateral negotiation. Top-down elements include goals relating to temperature (in Article 2.1a), mitigation (Article 4.1), adaptation (Articles 2.1b and 7.1) and finance (Article 2.1c and paragraph 53 of the Paris decision19), as well as mandatory review (Article 13) and a global stock-take (Article 14). As of October 2018, 177 countries had submitted their first NDCs, demonstrating near-universal participation in mitigation (consult the NDC registry at http://www4.unfccc.int/ndcregistry/Pages/Home.aspx). This is in contrast to the Kyoto Protocol, which in 1997 negotiated strong mitigation commitments only for developed countries. The scale and intensity of the challenge requires developing countries - even though they have contributed less to the problem14 - to also contribute to the solution. Developed countries will need to rethink their development paradigm. Collectively, the sum of NDCs puts us on a path towards 2.7-3.1 °C, although much depends on what countries do after 2030.20

Achieving national development goals, the SDGs and contributing to the Paris Agreement will require innovative development paths - which should be informed by long-term GHG development strategies (Article 4.19). South Africa's NDC contains a mitigation component with absolute numbers - keeping GHG emissions between 398 and 614 Mt CO2-eq in 2025 and 2030, to be achieved in the context of development. The challenges are particularly sharp in South Africa, which with its persistently high Gini coefficient and coal-based energy economy can be seen as a litmus test for addressing both inequality and mitigation.

Development pathways that reduce inequality and GHG emissions

How to reduce inequality and GHG emissions? This question frames the overall outcome that is required in South Africa and the world. It is deliberately posed simply, and suggests a state-of-the-world outcome. Answers to this question are well beyond the control of any single actor or institution, never mind any academic. Yet the overall question is useful to keep in mind in addressing more precise research questions.

Research question

How could innovative development pathways reduce inequality and GHG emissions? This question will require a long time and many minds to address. As any good long-term research question should, it raises further questions. What innovation is needed to follow such development pathways?21 How do GHG emissions and inequality correlate in South Africa, considering multiple dimensions of inequality and drivers of GHG emissions? How does that compare to other countries? How do we need to think differently, to shift to new development pathways that both reduce inequality and enhance mitigation? What are the implications for systems, policy, technology, investment, goals and mind-sets? Given that past patterns of development have 'baked in' high emissions into existing energy infrastructure22 - how do we avoid repeating the mistake?

Approach

How do researchers best think about normative issues, such as procedural and distributional equity, which are integral to inequality and mitigation? The approach in this article is to aim at rigorous analysis, but not pretend to be value free. Good analysis must be based on best available data and replicable methodologies, seeking to be as systematic as possible. As a community of scholars, we continually must check for confirmation bias, and remain open to results that we do not expect or like. But rather than pretending to know a universal truth, we do better by stating upfront the values we hold and any conscious biases that may influence the analysis. This author has made clear that key goals should be zero carbon and reduced inequality23 - and zero poverty and zero impacts. These are matters of investigation, as well as important goals to adopt. Having said that, the remainder of this section sets out means for rigorous analysis.

Towards a theoretical framework

Research on inequality and mitigation must draw on multiple disciplines - within each community of practice and a fortiori across them. Energy research has no single theory and analysis of mitigation draws on several disciplines - political studies, economics, social sciences, engineering and more. Scholars investigating inequality similarly come from a range of disciplines - perhaps most often from economics, but also sociology and other social sciences. Research on inequality and mitigation is necessarily interdisciplinary, and in Winskel's terms, requires not just cognate but radical interdisciplinarity.24 Furthermore, co-production of knowledge with a range of stakeholders increases the influence of research dramatically,25,26 so that transdisciplinarity becomes essential. There are no existing theories for such research. Constructing theoretical frameworks which borrow, rather eclectically, from a range of theories, is both a strength and a weakness. The weakness lies in not having a unifying explanatory theory, which can lead to lazy thinking. The strength is that the diversity of theoretical approaches ensures creative tensions, conducive to innovation and quite capable of systematic arrangement. A theoretical framework for inequality and mitigation is an important objective.

The real-world challenges of inequality and mitigation in the 21st century require systems thinking. The leverage points to intervene in systems were compellingly outlined by Meadows, who went on to warn that it would be a terrible mistake to assume that 'here at last, is the key to prediction and control'27 and to advise to remain humble28. The pedagogy of inequality and mitigation should be iterative, drawing on Freire's action-reflection-action cycles.29 An updated version of continuous learning and adjustment might be called adaptive management, which is relevant to both inequality and climate change.30

Quantitative and qualitative analyses

Addressing the research question will require complex problem-solving using both quantitative and qualitative analyses. The existing literature on mitigation has historically been based on techno-economic modelling.31,32 Broadly, three areas for reducing GHG emissions from energy use and supply have been identified: (1) improving energy efficiency, (2) changing the fuel mix to lower carbon sources and (3) moving to less energy- and emissions-intensive sectors of the economy.33 Careful modelling and analysis provides rigour in complex problem-solving, has inherent value and will continue to provide a counter-balance for hand-waving analysis of mitigation scenarios - or indeed development pathways.

To address inequality and mitigation, correlations will be important. Learning from research on Indonesia10 and internationally34, we need to understand how GHG emissions and inequality correlate in South Africa. Some methodologies that are applicable to inequality within countries include the use of input-output tables10 or social accounting matrices, in order to attribute all emissions within a country to households; and decomposition analysis of emissions growth drawing on the Kaya identity35. Irfany and Klasen10 found that 'aggregate consumption is the most important driver of carbon footprints', so having consumption-based GHG inventories for South Africa will be an important research task. It is important to distinguish direct GHG emissions in households, indirect GHG emission elsewhere in the economy (e.g. energy, steel, cement) and those embodied in trade.36 Further extensions should consider concentration of assets (as distinct from income), urban-rural differences or spectrums, differences in locational value because of different places of production or consumption37, inequalities in skill levels, direct and indirect energy use38, and other potentially significant contextual drivers. In many African countries, although less so in South Africa, the problem is one of avoiding emissions, rather than reducing from high levels.39 Comparative analysis between countries would be the next step (of inequality within each) - and points to the need for an international team of researchers.

Research on inequality among countries (as in SDG 10) would likely draw on metrics such as the Gini coefficient40 (and Lorenz curves), the Theil Index41, and an extensive literature on environmental Kuznets curves, including application to climate change42. The Gini coefficient has been applied to carbon, with the finding that '70% of carbon space in the atmosphere has been used for unequal distribution, which is almost the same as that of incomes in a country with the biggest gap between the rich and the poor in the world'43. Some initial global modelling of inequality and mitigation suggests that there may not be only trade-offs, finding that 'aggressive inequality reduction…would realistically increase GHG emissions by less than 8%' over several decades; however, overall reductions are required rather than limiting increases, and the authors point to the need to 'deeper under-explored linkages and synergies between reducing income inequality and climate change'34. Another perspective is that 1.5 °C and SDGs can remain within reach with 'low energy demand scenarios'44 globally; yet how this plays out in poor communities and countries remains important.

Energy is only one - albeit an important - input for development. Research needs to understand inequalities in energy use and supply. Sustainable energy for all is a critical challenge in South Africa, Africa, other developing countries and the world in the 21st century. Much energy analysis tends to focus on GHG emissions associated with energy production - the use of coal, oil and gas to generate electricity and supply liquid fuel.45,46 Yet patterns of consumption are important to understand inequalities. Energy analysis of household consumption is critical in this regard and analysis of changing patterns in India38 is highly relevant to South Africa. Addressing highly unequal access to affordable modern energy services in many developing countries47 is a key input to development. The question is how this can be done in a low emissions manner.

Renewable energy for electricity is one rapidly growing system that promises synergies. Only a few years ago, the assumption was that renewable energy technologies imposed an incremental cost, being more expensive than relatively cheaper fossil fuels. With very rapidly falling costs, there is now a net benefit - globally48, in sub-Saharan Africa49 and South Africa50. Already coal communities are being impacted by mine closures, with other mining sectors increasingly being automated. Will workers from those communities find employment in emerging sectors, including energy service companies and renewable energy? A just energy transition is key to development pathways to provide jobs and livelihoods for the future.

Yet existing energy systems in developing countries are not able to make transformative inputs to achieving development outcomes for the well-being of the majority of people. Hundreds of millions of people in developing countries still lack access to affordable energy services.47 On current trends, it will take until 2080 to reach universal access to electricity across the African continent51 - and move beyond fuel from solid biomass (essentially fuelwood and charcoal), on which 4 out of 5 African households depend52.

Development pathways

Development pathways, as distinct from mitigation pathways, are key to our (future) analytical frameworks. What development pathways would meet South Africa and Africa's development objectives? What storylines reduce poverty, inequality and GHG emissions?

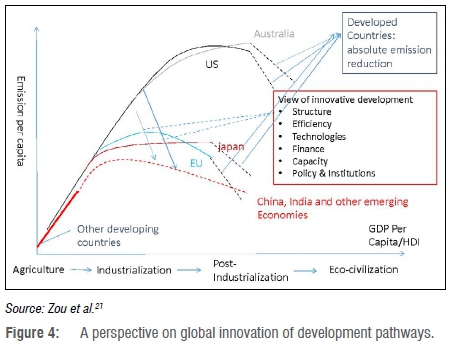

Figure 4 offers one conceptual framing to think about such questions. If countries followed the innovative development pathways presented in Figure 4, would this reduce the patterns of income inequality shown earlier in Figure 1?

The challenges of inequality and climate change mitigation in the context of development are each 'wicked problems'; combining them constitutes a super-wicked problem.53 Indeed, the inequality-mitigation nexus as a super-wicked problem poses fundamental questions about the future of industrial civilization.54 In our country, the extreme degrees of inequality threaten to undermine prospects of a better life. Globally, the high-emission development paths which developed countries have followed cannot be the model for the future.14,55-57 What is needed is to change from emissions intensive development paths34 to innovative development pathways21 that reduce emissions, poverty, inequality and emissions. The research agenda should consider 'living well' with less - so scenarios of lower demand globally44 are helpful to our analysis - but cannot come at the expense of those in energy poverty.

Is our education system training young people with the appropriate skills for a major transition? Three key skills that will be needed in future are 'complex problem-solving, critical thinking and creativity'58. Will there be kinds of work that are irreducibly human? The future will likely be very different from our past and present, so understanding change is crucial to unpacking inequality and mitigation.

Understanding change

How do we change development pathways?33 It seems safe to assume that no single actor is in charge of development. No single government, company, union, investor, social movement, city or other agent of change on their own changes development pathways - these are the result of myriad decisions by large numbers of actors. To address this research question, understanding of change agents (those preceding and others), determinants of change, and adaptive management, among other issues, is required. Are key determinants of change to be found in material conditions, ideas, institutions59,60, or networks, recalling that the mind-set or paradigm is a high-level lever to intervene in a system?27 How must we think differently, in order to shift to new development pathways that reduce inequality and GHG emissions?

How must policy change and what are specific policy instruments that can reduce inequality and GHG emissions? While policy is no silver bullet, and needs to be understood as part of systems, policy analysis is an important area requiring more research. Research should examine policy instruments ranging from a universal basic income to pricing with pro-poor revenue recycling,61 investments in education, a more progressive tax system, a tax on financial speculation, and more. Bearing in mind the future of work, a 'tax on robots' is another instrument requiring close attention. It will be important to pilot, demonstrate and replicate specific instruments; to learn from both successes and failures, and to adapt as we learn by reflecting on action.

Technology is changing very rapidly. Artificial intelligence may be a key component of what the founder of the World Economic Forum thinks may be a 'fourth industrial revolution'62, while others talk about 'post-capitalism'63. Regardless of framing, addressing the super-wicked problem of inequality and mitigation requires thinking about the future - of work, capital, labour and society in general. With the rise of artificial intelligence and biotechnology, much of humanity may become militarily and economically useless64, with much of today's paid labour replaced by machines. In a 'post-work' future, the contest may not be about capital and labour, but around energy and resources.65 This process may further entrench inequality, especially in emerging economies with low skill levels. The patterns of investment will have to shift dramatically from those of the past.

Pursuing a focus on inequality and mitigation within the broader fields of development and climate change should also attract more black South African scholars. The climate community of practice in South Africa is still largely composed of older white men (including the present author). Transformation is essential, and linking mitigation to poverty and inequality can be expected to ground the analysis in issues of interest to emerging scholars.

Managing change to address super-wicked problems in a complex world requires adaptive management. O'Brien and Selboe30 argue that, beyond technical problems, management of complex adaptive systems requires changes in people's mind-sets, shedding entrenched ways of thinking, tolerating disequilibria - and considering change other than as a linear pathway. Adaptive management is needed to deal with dynamic, social, human and emergent complexity - all of which characterise inequality and mitigation. A long-term time frame is needed, but not a plan from here to there. It is all about planning, not a plan; adapting as you go along rather than rigidly implementing. An objective of the agenda proposed here must be applying adaptive management to follow innovative development pathways, from local to global scales, and addressing long-term problems that require urgent action.

Beyond management, the challenges of inequality and mitigation will require a new social contract.66 Such a social contract accepts that the poor have to be lifted out of poverty, with little impact on emissions; that richer households can be happier with less; and that the aspirations of middle classes should shift from having more to living well.

Conclusion

Reducing inequality and GHG emissions are key challenges of the 21st century. An agenda for research and co-production of knowledge, framed by the question of how innovative development pathways could reduce inequality and GHG emissions, has been proposed here.

The agenda starts at the national level, to pursue multiple development goals - notably reducing inequality and poverty, and finding low emissions paths to achieve those objectives. It is by action at local scale that we must aim to achieve the SDGs and Paris Agreement globally.

The complex nature of both inequality and mitigation requires interdisciplinary research and a theoretical framework will necessarily draw on multiple theories. The article calls on communities of scholars to work towards a theoretical framework to understand development paths that reduce inequality and mitigation.

The theoretical framework will require a very wide range of methods, both qualitative and quantitative. Engaged scholars of inequality and mitigation will need expertise in consumption-based accounting as much as policy analysis, to name just two examples. Complex problem-solving, critical thinking and creativity will be key skills in thinking about points to intervene in complex systems. The research must be rigorous while declaring its goals to reduce inequality and emissions upfront. While excellent research is an essential foundation and an international collaboration is proposed, co-production of knowledge makes a bigger difference. Learning by doing, together with a range of stakeholders, in a continual action-reflection-action cycle is an essential pedagogy.

Meeting the challenges of inequality and mitigation requires understanding how change happens - change of policy, technology, investment, but perhaps more fundamentally, some determinants and agents of change. This information will be valuable for adaptive management of complex systems. Innovating in development pathways that will shift countries from development pathways from emissions-intensive to low emissions development pathways, while reducing inequality within and across countries - those are certainly complex adaptive systems.

What is required is no less than a new social contract, in which the rich live better with less, the poor are lifted out of poverty, and middle-class aspirations shift from having more to living well. The vision of a world with less inequality and fewer emissions is a bold but necessary one, and achieving it is a challenge worthy of concerted action.

References

1.South African National Planning Commission. Our future - make it work: National development plan 2030. Pretoria: The Presidency; 2012 [cited 2012 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.npconline.co.za/pebble.asp?relid=757 [ Links ]

2.United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. A/RES/70/1: Sustainable Development Goals. New York: United Nations; 2015. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf [ Links ]

3.United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Paris Agreement. Annex to decision 1/CP.21 document FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1. Paris: UNFCCC; 2015. Available from: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf#page=2 [ Links ]

4.Stiglitz JE. The great divide: Unequal societies and what we can do about them. New York: Norton; 2015. [ Links ]

5.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report: Fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: IPCC; 2014. Available from: http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/syr/SYR_AR5_SPM.pdf [ Links ]

6.Phakeng M. Remarks in presentation in selection process for Vice Chancellor. Cited in: Farber T. Strong‚ qualified and able: Two women battle it out for UCT top post. TimesLive 2018 February 22. Available from: https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2018-02-22-strong-qualified-and-able-two-women-battle-it-out-for-uct-top-post/ [ Links ]

7.Pikkety T. Capitalism in the twenty-first century. Paris: Éditions du Seuil and Harvard University Press; 2013. [ Links ]

8.Leibbrandt M, Ranchhod V. A review of the economics of income inequality literature in the South African context [document on the Internet]. c2017 [cited 2018 Oct 29]. Available from: http://www.psppd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Inequality-in-SA_A-review-of-the-economics-of-income-inequality-literature-in-the-SA-context.pdf [ Links ]

9.Milanovic B. Global income inequality by the numbers: In history and now - An overview. Policy Research Working Paper 6259. Washington: Development Research Group, Poverty and Inequality Team; 2012. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/959251468176687085/pdf/wps6259.pdf [ Links ]

10.Irfany MI, Klasen S. Affluence and emission tradeoffs: Evidence from Indonesian households' carbon footprint. Environ Develop Econ. 2017;22:546-570. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X17000262 [ Links ]

11.Tait L. Towards a multidimensional framework for measuring household energy access: Application to South Africa. Energy Sustain Develop. 2017;38:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2017.01.007 [ Links ]

12.Clark D, Houston R. The carbon map. No date [cited 2018 Oct 29]. Available from: http://www.carbonmap.org/#Historical [ Links ]

13.Shue H. Global environment and international inequality. Int Affairs. 1999;75:531-544. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00092 [ Links ]

14.Agarwal A, Narain S. Global warming in an unequal world: A case of environmental colonialism. New Delhi: Centre for Science and Environment; 1991. Available from: http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/GlobalWarming%20Book.pdf [ Links ]

15.Sokona Y, Denton F. Climate change impacts: Can Africa cope with the challenges? Clim Policy. 2001;1:117-123. https://doi.org/10.3763/cpol.2001.0110 [ Links ]

16.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change 2007: Synthesis report: Fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: IPCC; 2007. [ Links ]

17.Oberthür S, Bodle R. Legal form and nature of the Paris Outcome. Clim Law. 2016;6:40-57. [ Links ]

18.Klein D, Carazo P, Bulmer J, Doelle M, Higham A, editors. The Paris Agreement on climate change: Analysis and commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017. [ Links ]

19.United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Decision 1/CP.21, document FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1 Paris: UNFCCC; 2015. Available from: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf [ Links ]

20.Rogelj J, Den Elzen MGJ, Höhne N, Fransen T, Fekete H, Winkler H, et al. Paris Agreement climate proposals need boost to keep warming well below 2°C. Nature. 2016;534:631-639. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18307 [ Links ]

21.Zou J, Fu S, Liu Q, Ward J, Ritz R, Jiang K, et al. Pursuing an innovative development pathway: Understanding China's NDC [document on the Internet]. c2016 [cited 2018 Oct 29]. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/312771480392483509/pdf/110555-WP-FINAL-PMR-China-Country-Paper-Digital-v1-PUBLIC-ABSTRACT-SENT.pdf [ Links ]

22.Davis SJ, Caldeira K, Matthews D. Future CO2 emissions and climate change from existing energy infrastructure. Science. 2010;329:1330-1333. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188566 [ Links ]

23.Schultz D. Low carbon energy economy with socioeconomic benefits. Mail & Guardian. 2018 June 29. Available from: https://mg.co.za/article/2018-06-29-00-low-carbon-energy-economy-with-socioeconomic-benefits [ Links ]

24.Winskel M. The pursuit of interdisciplinary whole systems energy research: Insights from the UK Energy Research Centre. Energy Res Social Sci. 2018;37:74-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.012 [ Links ]

25.Orford M, Raubenheimer S, Kantor B. Climate change and the Kyoto Protocol's Clean Development Mechanism: SouthSouthNorth - stories from the developing world. Cape Town: Double Storey; 2004. [ Links ]

26.Boulle M, Torres Gunfaus M, Kane L, Du Toit M, Winkler H, Raubenheimer S. MAPS approach: Learning and doing in the global South [document on the Internet]. c2015 [cited 2018 Oct 29]. Available from: http://www.mapsprogramme.org/wp-content/uploads/The-MAPS-DNA_02-07-2015_Final-.pdf [ Links ]

27.Meadows D. Leverage points: Places to intervene in the system. Hartland VT: The Sustainability Institute; 1999. [ Links ]

28.Meadows D. Dancing with systems. Whole Earth Winter. 2001:58-63. [ Links ]

29.Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Continuum; 1970. [ Links ]

30.O'Brien K, Selboe E. The adaptive challenge of climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139149389 [ Links ]

31.Merven B, Arndt C, Winkler H. The development of a linked modelling framework for analysing socio-economic impacts of energy and climate policies in South Africa. UNU WIDER working paper 2017/40 [document on the Internet]. c2017 [cited 2018 Oct 29]. Available from: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/wp2017-40.pdf [ Links ]

32.Pye S, Bataille C. Improving deep decarbonization modelling capacity for developed and developing country contexts. Clim Policy. 2016;16:S27-S46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1173004 [ Links ]

33.Winkler H, Marquard A. Changing development paths: From an energy-intensive to low-carbon economy in South Africa. Clim Develop. 2009;1:47-65. https://doi.org/10.3763/cdev.2009.0003 [ Links ]

34.Rao ND, Min J. Less global inequality can improve climate outcomes. WIREs Clim Change. 2018;9, e513, 6 pages. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.513 [ Links ]

35.Kaya Y, Yokobiri K. Environment, energy and economy: Strategies for sustainability. Tokyo: United Nations University Press; 1997. [ Links ]

36.Davis SJ, Caldeira K. Consumption-based accounting of CO2 emissions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5687-5692. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0906974107 [ Links ]

37.Milanovic B. The haves and the have-nots: A brief and idiosyncratic history of global inequality. New York: Basic Books; 2011. [ Links ]

38.Pachauri S. An energy analysis of household consumption: Changing patterns of direct and indirect use in India. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007. [ Links ]

39.Davidson O, Halsnaes K, Huq S, Kok M, Metz B, Sokona Y, et al. The development and climate nexus: The case of sub-Saharan Africa. Clim Policy. 2003;3:S97-S113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clipol.2003.10.007 [ Links ]

40.Yitzhaki S. Relative deprivation and the Gini coefficient. Quart J Econ. 1979;93:321-324. https://doi.org/10.2307/1883197 [ Links ]

41.Conceição P, Galbraith JK. Constructing long and dense time-series of inequality using the Theil Index. East Econ J. 2000;26:61-74. [ Links ]

42.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change 2014: Mitigation of climate change. IPCC Working Group III contribution to the fifth assessment report. Geneva: IPCC; 2014. Available from: http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg3/ [ Links ]

43.Teng F, He J, Pan X, Zhang C. Metric of carbon equity: Carbon Gini Index based on historical cumulative emission per capita. Adv Clim Change Res. 2016;2:134-140. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1248.2011.00134 [ Links ]

44.Grubler A, Wilson C, Bento N, Boza-Kiss B, Krey V, McCollum DL, et al. A low energy demand scenario for meeting the 1.5 °C target and sustainable development goals without negative emission technologies. Nature Energy. 2018;3:515-527. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-018-0172-6 [ Links ]

45.Green F, Denniss R. Cutting with both arms of the scissors: The economic and political case for restrictive supply-side climate policies. Clim Change. 2018;150(1-2):73-87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2162-x [ Links ]

46.Johannson TB, Williams RH, Ishitani H, Edmonds J. Options for reducing CO2 emissions from the energy supply sector. Energy Policy. 1996;24:985-1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(96)80362-4 [ Links ]

47.Winkler H, Simões AF, La Rovere EL, Alam M, Rahman A, Mwakasonda S. Access and affordability of electricity in developing countries. World Develop. 2011;39:1037-1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.02.021 [ Links ]

48.International Renewable Energy Agency, International Energy Agency, Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (IRENA, IEA, REN21). Renewable energy policies in a time of transition. Paris: IRENA, OECD/IEA, REN21; 2018. Available from: http://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2018/Apr/IRENA_IEA_REN21_Policies_2018.pdf [ Links ]

49.Kruger W, Eberhard A. Renewable energy auctions in sub-Saharan Africa: Review, lessons learned and recommendations. Cape Town: GSB, University of Cape Town; 2018. http://www.gsb.uct.ac.za/files/RenewableEnergyAuctionsSSA.pdf [ Links ]

50.ERC, CSIR, IFPRI. The developing energy landscape in South Africa: Technical report. Cape Town: Energy Research Centre, University of Cape Town; 2017. http://bit.ly/2ABamkz [ Links ]

51.Africa Progress Group Panel. Power people planet: Seizing Africa's energy and climate opportunities. Abeokuta, Nigeria: Africa Progress Group; 2015. Available from: https://www.seforall.org/sites/default/files/l/2015/06/APP_REPORT_2015_FINAL_low1.pdf [ Links ]

52.Bazilian M, Nussbaumer P, Rogner HH, Brew-Hammond A, Foster V, Pachauri S, et al. Energy access scenarios to 2030 for the power sector in sub-Saharan Africa. Util Policy. 2012;20:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2011.11.002 [ Links ]

53.Levin K, Cashore B, Bernstein S, Auld G. Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sci. 2012;45:123-152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-012-9151-0 [ Links ]

54.Monbiot G. Requiem for a crowded planet [webpage on the Internet]. c2009 [cited 2011 Oct 08]. Available from: http://www.monbiot.com/archives/2009/12/21/requiem-for-a-crowded-planet/ [ Links ]

55.Pan J. Emissions rights and their transferability: Equity concerns over climate change mitigation. Int Environ Agreements Politics Law Econ. 2003;3:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021366620577 [ Links ]

56.Mwandosya MJ. Survival emissions: A perspective from the South on global climate change negotiations. Dar es Salaam / Bangkok: Dar es Salaam University Press / Centre for Energy, Environment, Science and Technology; 2000. [ Links ]

57.Smith KR. The natural debt: North and South. In: Giambelluca T, Herderson-Sellers A, editors. Climate change: Developing southern hemisphere perspectives. New York: John Wiley; 1996. p. 423-448. [ Links ]

58.Ramaphosa C. Statement by His Excellency President Cyril Ramaphosa during the Open Session of the 10th BRICS Summit, 2018 July 26; Sandton International Convention Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa. Available from: http://www.dirco.gov.za/docs/speeches/2018/cram0726.html [ Links ]

59.Cox RW. Social forces, states and world orders: Beyond international relations theory. Millennium. 1981;10:126-155. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298810100020501 [ Links ]

60.Simon R, Hall S. Gramsci's political thought. London: Lawrence & Wishart; 2002. [ Links ]

61.Winkler H. Reducing energy poverty through carbon tax revenues in South Africa. J Energy South Africa. 2017;28:12-26. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3051/2017/v28i3a2332 [ Links ]

62.Schwab K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. London: Penguin; 2017. [ Links ]

63.Mason P. Post-capitalism: A guide to our future. London: Penguin; 2015. [ Links ]

64.Harari YN. Homo Deus: A brief history of tomorrow. London: Harvill Secker; 2016. [ Links ]

65.Srnicek N, Williams A. Inventing the future: Post-capitalism and a world without work. London: Verso Books; 2015. [ Links ]

66.Winkler H, Boyd A, Torres Gunfaus M, Raubenheimer S. Reconsidering development by reflecting on climate change. Int Environ Agreements. 2015;15:369-385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-015-9304-7 [ Links ]

67.Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU). Income comparison tool [webpage on the Internet]. No date [cited 2018 Oct 29]. Available from: http://www.saldru.uct.ac.za/income-comparison-tool/ [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Harald Winkler

harald.winkler@uct.ac.za

Published: 27 November 2018